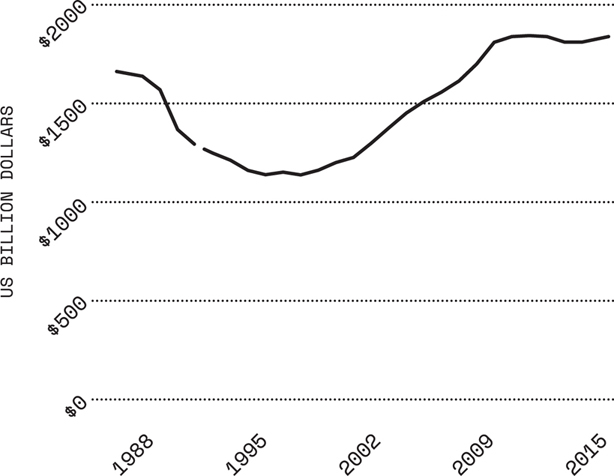

Figure 1.1 World military expenditure, 1988‒2015 (constant 2014 US$bn)

Note: The absence of data for the Soviet Union in 1991 means that no total can be calculated for that year.

Source: SIPRI, Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2015.

HIGHER DEFENSE SPENDING EQUALS INCREASED SECURITY

‘If you want peace, prepare for war.’

So goes the much-repeated phrase, taken to heart around the globe. Indeed, the world spends a great deal preparing for war: at least $1,676bn in 2015.1 With such high levels of spending, and the innumerable threats that arms purchases are said to protect us from, it would be easy to accept this adage at face value: why on earth else would responsible governments pour such huge sums into military spending?

Unfortunately, the reality is a lot more complicated. While most reasonable people would agree that states should be able to legitimately defend themselves and their citizens, it is unclear that large outlays on defense make a consistently measurable difference in providing security to the countries that buy weapons. Moreover, there is solid evidence showing that, in certain instances, spending money on buying weapons may actually decrease a country’s security. Just one of these is the situation referred to as the classic ‘security dilemma’ of setting arms races in motion: three others are also explored in this chapter. For example, in states where the purchasing government is undemocratic or corrupt, there are incontrovertible examples where a government uses weapons to the detriment of the security of citizens.

HOW MUCH IS SPENT?

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) estimates world military spending in 2015 at $1,676bn.2 As a share of global economic output (gross domestic product, or GDP), this amounts to 2.3% globally.3 This is almost certainly an underestimate, as it excludes some countries such as North Korea where meaningful dollar figures cannot be calculated, and cannot capture the considerable ‘off-budget’ military spending that occurs in many countries, for example by using oil revenues to buy arms without including it in the national budget.

During the Cold War, both NATO and the Warsaw Pact spent vast amounts on their militaries. For over forty years the US and the Soviet Union engaged in an arms race, both conventional and nuclear. Each did so largely out of fear of the other’s intentions, seeking nuclear deterrence and the capability to win a third world war, while at the same time generating increased fears and insecurity in the other. When the Cold War ended, the Western public discovered that NATO had hugely inflated their estimates of the Soviet military capability. The fears were real, but they had been exaggerated.

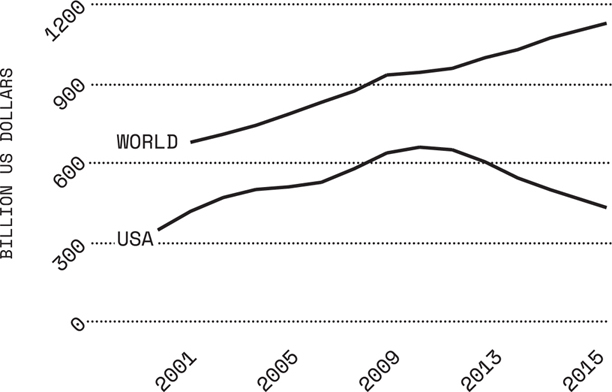

With the end of the Cold War, there was a great deal of hope that countries would divert defense funds into social development: what was known as the ‘peace dividend’.4 Signs were initially good: at the end of the Cold War, military spending fell significantly in real terms (i.e. adjusted for inflation) up to the mid-1990s. But military spending started increasing again after 1998, and much more rapidly after 2001, in the aftermath of 9/11 (see Figure 1.1). Between 2011 and 2014, the global economic crisis and the austerity that was attendant upon it precipitated a fall in global defense expenditure. In 2015, however, global defense expenditure increased from its 2014 level—a sign that defense expenditure is regaining ground lost during the economic crisis. And what was particularly notable prior to 2015’s turnaround was how much the ‘rest of the world’ picks up the slack in defense expenditure: between 2011 and 2014, as defense budgets were reduced in the West, the ‘rest of the world’ was increasing its expenditure year-on-year.

Figure 1.1 World military expenditure, 1988‒2015 (constant 2014 US$bn)

Note: The absence of data for the Soviet Union in 1991 means that no total can be calculated for that year.

Source: SIPRI, Trends in World Military Expenditure, 2015.

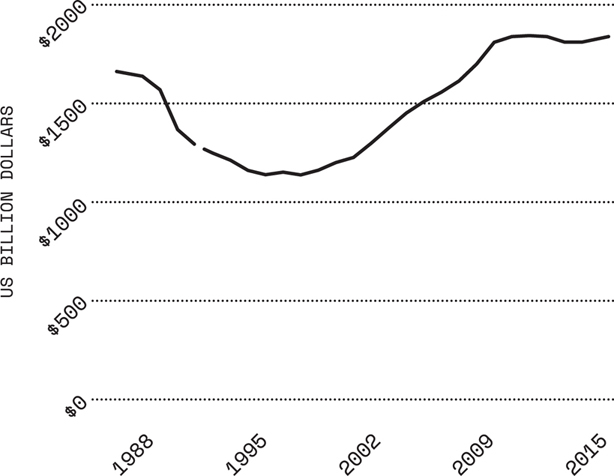

Figure 1.2 15 countries with the highest military expenditure in 2015

Source: Extrapolated from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2016.

Despite recent falls in the West and increases in the rest of the world, Western countries still account for a majority of global military spending. NATO members, including the US, spent a total of $904bn in 2015, 53.9% of total world military spending.5 Other countries that the US classes as ‘major non-NATO allies’, including Japan, Australia and Israel, accounted for another 10% of the total. Eight of the top fifteen military spenders worldwide are either NATO members or major US non-NATO allies. Nonetheless, countries outside the West have become more prominent amongst the major spenders, with China, Saudi Arabia and Russia now the second, third and fourth largest spenders worldwide.6

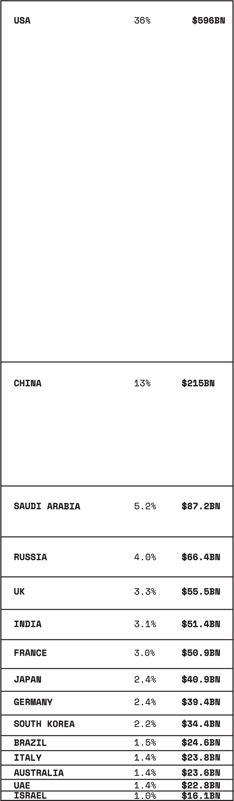

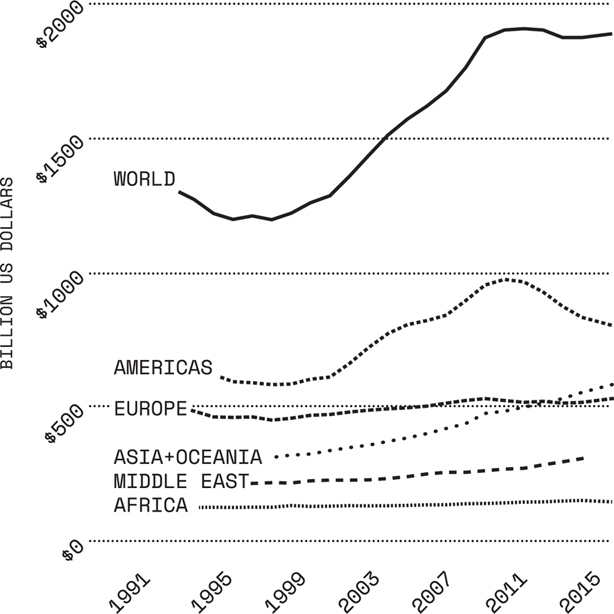

The dominance of the top fifteen spenders should not obscure another important trend: military expenditure is growing rapidly globally, even in some of the poorest regions of the world. Indeed, SIPRI identifies twenty-three countries that have doubled their military spending between 2004 and 2013. Among them are some of the world’s poorest nations. In Africa, for example, military spending rose over 8% in 2013 and 5.9% in 2014—adding up to a 91% increase overall since 2005.7 Admittedly military expenditure fell in Africa in 2015 by 5.3% (the first time in eleven years) to $37bn, but this is still a massive 68% higher than it was in 2006.8 This is matched elsewhere: world military expenditures, despite a slight leveling in 2013, have steadily climbed over the past decade—outpacing economic growth.9 China, the nation with second highest military spending, has increased its defense budgets by double digits almost every year for the past twenty, well outpacing even its impressive GDP growth and sparking defense spending increases in wary regional neighbors South Korea and Vietnam.10 Further, Japan joined the top ten military spenders in 2013 and, in 2015, approved the decision to reverse its post-World War II constitutionally engraved ban on its forces fighting overseas.11 Russia has increased its military spending 92% since 2010 alone.12

Regional increases, possibly indicating arms races (where increasing military expenditure of one country leads another to spend more, thereby encouraging the original country to spend even more, triggering further regional spending and so on), have occurred in the Middle East, where Saudi Arabia vastly expanded its defense budget by 97% between 2006 and 2015; in Africa, where overall expenditures have been growing by 5‒8% annually (until a surprising drop in 2015) with Algeria and Angola leading the way; and in Asia and Oceania, which witnessed a 64% increase between 2006 and 2015 (and a 5.4% increase in 2015 alone), spearheaded by Chinese defense budget increases.13

Figure 1.3 Defense spending by region, 1992–2015 (constant 2014 US$bn)

Source: Extrapolated from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2015.

Despite regional and global increases, the United States remains far and away the world’s largest spender on its military, spending more than the next ten nations in the world combined, and four times its closest rival, China. Because it spends so much beyond any other country, it is worth a close look at the purchasing power of this super-sized budget.

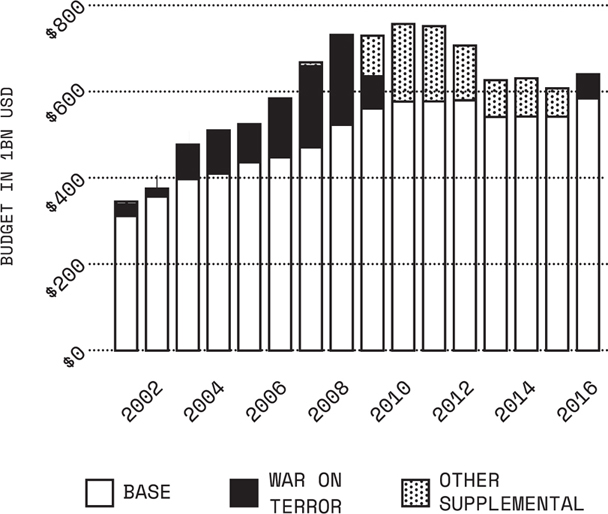

Defense spending consumed 16.3% of the total US federal budget in 2015.14 In absolute terms, its total national defense spending in 2013, even discounting funding for the ongoing war in Afghanistan, remained near what it was in 1985, the previous peak (it should be pointed out that, as the US has become richer in the interim, defense spending as a percentage of GDP has fallen: it was 6.8% at the height of the Reagan reequipping era, 5.7% in 2011 and 4.5% in 201515). In that era, of course, historically high defense spending was deemed necessary as part of an existential struggle with the USSR (although it has subsequently emerged that the USSR’s military capacity was often overstated).16 For the year 2016, the Pentagon enjoys a $534.3bn base budget and the $50.9bn Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) budget (a total of $585.2bn).17 Further, the US is currently on track to fund the most expensive weapons program in human history, the F-35 fighter jet, which will cost roughly $1.4trn to build and operate over its lifetime.18

Figure 1.4 US military spending versus the rest of the world, 2000–2015 (constant 2014 US$bn)

Source: Extrapolated from the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database 2015.

Figure 1.5 DoD budgets, FY 2001–2016

Note: from 2010 onwards the category ‘Global War on Terror’ is no longer used in the accounting of the Comptroller General of Defense. The Global War on Terror is replaced by the account line Overseas Contingency Operations. This has been added to other discretionary supplements, such as spending on Hurricane Sandy relief in 2013, to produce the figure for ‘other supplemental’.

Source: Extrapolated from Office of the Under Secretary for Defense (Comptroller), National Defense Budget Estimates for FY2016, United States Department of Defense, March 2015, Table 2-1, p. 22, accessed May 31, 2016, http://comptroller.defense.gov/Portals/45/Documents/defbudget/fy2016/FY16_Green_Book.pdf.

The Pentagon’s spending is in addition to the $71.6bn intelligence budget for fiscal year 2016, which includes drone warfare conducted in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and massive digital surveillance channeled, for example, through the National Intelligence Program, including the CIA, NSA, National Reconnaissance Office and National Geospatial-Intelligence Program.19 If all these items are added together (the base budget, contingency spending and intelligence) for 2016, the total is $656.8bn: a truly enormous sum.

DOES DEFENSE SPENDING LEAD TO SECURITY?

With so much being spent on defense, it is only natural that we ask whether or not it is being well spent. Unfortunately, there are a number of ways in which spending on defense may actually make us less secure. We will discuss the most common ways here, but there are other, more complicated, impacts that defense spending can have on security around the world, which we will address at the very end of this chapter.

The security dilemma

The first way in which military spending can actually reduce security is through what is known in international relations theory as the ‘security dilemma’,20 or the ‘spiral of insecurity’. The ‘security dilemma’ occurs when a state with no hostile intentions believes that states around it, while not necessarily expressing any outward enmity, could pose a long-term security threat. The state responds by increasing its own sense of security through building up its defense capacities. However, states around it see this increase in defense spending, and come to believe that the original state now has hostile intentions; they, in turn, increase their own defense capacities. This cycle continues as both parties increasingly divert resources towards their own defense, leading to an arms race. This ‘spiral of insecurity’ can, in the worst case scenario, lead to actual conflict. This is not to suggest that conflict follows inexorably from arms races; the data is much too complicated for that.21 And, as we will demonstrate later, arms sales often have nothing to do with perceived or real security threats. But in certain cases arms races undoubtedly play a role, such as in the case of the developments that led to World War I.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Germany’s leaders had come to believe that it was being surrounded by hostile forces including Russia, France and Great Britain. In response, Germany started to build up its military forces, in particular its naval forces, which all other parties began to believe was evidence of Germany’s ill intentions. Great Britain, which had built its military power on its navy, was particularly alarmed. The other three parties, seeing this, also increased their weapons, leading to an enormous arms race. This race created tensions between all the states; so much so that, when a political crisis unfolded upon the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand, Austria-Hungary and Russia both mobilized and Germany then invaded its neighbors, provoking one of the deadliest conflicts in human history. The arms race may not have been the cause of World War I (human affairs are always more complicated than that), but it was a substantial contributor to the tensions that led to war.

Is China’s Growing Military Expenditure the Result of the ‘Security Dilemma’?

China’s rapidly rising military expenditure and capabilities are generating considerable fears amongst some of its neighbors, especially Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and the Philippines; and all countries are all now increasing military spending in response.22 (Vietnam has been doing so for several years, the others more recently.) These states have also sought a closer relationship with the US, believing it can offer additional security. The US, meanwhile, is seeking to develop its regional forces to counter some of China’s growing capabilities in areas such as ‘anti-access area denial’ (weapons systems including missiles and submarines aimed at preventing or hampering US intervention in the region).23

But China’s military spending increases and its eagerness to modernize its military to be able to ‘win local wars under conditions of informatization’24 are themselves arguably a function of their insecurity in the face of overwhelming US military dominance in the Pacific, including China’s immediate vicinity. While the US (and its allies) may view its military power in the region as entirely benign in intent, issues such as US support for Taiwan, as well as US actions such as the invasion of Iraq and the accidental bombing of the Chinese embassy in Belgrade during the Kosovo war, mean that China does not view it in such a light.25 While it would be premature to see the situation in the Asia Pacific as an ‘arms race’, there is strong evidence of a security dilemma, whereby each party’s efforts to guarantee their own security are generating insecurity in others, and ultimately failing to increase security for any party. Real issues, largely concerning economic development, exist between Asian countries and their allies, but addressing them through an arms race only increases the risks.

In the context of the Obama administration’s ‘pivot to Asia’, pursuing US military dominance in the region runs the danger of increasing regional tensions and spurring an arms race with China. It is impossible to ignore the regional dimensions of the tensions in Asia, including the competition over control of the South China Sea and its energy resources. The question is whether a militarized approach on the part of the United States will make matters better or worse. China is seeking to become a genuine naval power in its own region. But to the extent that the United States increases its own naval presence in the area and arms local allies (often at their own request) to create a military bloc aimed at Beijing, China is more likely to accelerate its already rapidly growing military budget. China will also continue its investment in asymmetric forces such as anti-satellite weapons and cyber-warfare capabilities. A rapprochement between the US and China that promoted mutual economic and environmental interests would be far more likely to reduce tensions in the region than a US military build-up.

There’s no security in waste and corruption

The second way in which defense spending can decrease security is when the spending is wasteful or inflated due to corruption. Usually this involves the perennial problem of cost overruns in the defense sector, dragging projects years into overtime and absorbing scarce economic resources that could be spent on things that encourage security—like health, education and infrastructure.

But there is also a long history of defense spending funding the development and procurement of weapons that are strategically questionable and, in the worst cases, utterly dysfunctional. When corruption enters the picture (as we will discuss in Myth 5), defense transactions might only take place because of the illicit money to be earned, without any concern for real strategic need.

A prime recent example of wasteful defense spending is the littoral combat ship (LCS), a multi-purpose boat designed to serve a variety of functions, from attacking other surface ships, to hunting for mines, to moving in close to shore to insert Special Forces into an area. There are two different versions of the ship, one produced by Lockheed Martin and the other by Austal. Both have experienced serious performance problems and huge cost overruns, to the point where one LCS now costs over $780m, nearly double the originally projected price. In fact, the LCS program could be presented as a case study in how not to build a weapons system.26

One analyst described the LCS as ‘the warship that can’t go to war’.27 This is because it is being asked to do so many different missions that it does none of them well. The basic concept of the program was that the LCS would be a hull or seaframe that could carry one of three different ‘mission modules’ that would allow it to carry out different functions. There are too many problems with the ship to enumerate all of them here, but they include being overweight, and therefore unable to integrate new technology as it emerges; under-armored, and therefore extremely vulnerable to widely available anti-ship missiles; and under-crewed, making it difficult to respond to on-board emergencies or engage effectively in heavy combat. The existence of three different mission modules is useless in a crisis: it can take up to three days to change from one mission module to another, potentially costly delays in the case of a real emergency. The ship has also suffered hull cracks and electrical problems.

Perhaps worst of all, six LCSs were built and billions of dollars spent on them before they were tested in rough seas, against explosives or for basic survivability (i.e. the length of a ship’s useful service life). The problems are so extreme that the Obama administration’s secretary of defense has decided to cut the program from fifty-two to thirty-two ships. A further twenty ships will be built on top of the thirty-two, but they are to be built to a substantially new design, new enough that they will now be referred to as frigates not littoral combat ships.28

A particularly dirty case that involves both wasteful and useless military spending and allegations of corruption is the DCNS scandal in Malaysia. In 2002, Malaysia signed a €1bn deal to purchase two Scorpene submarines from the French company DCNS and its partner Navantia.29 Since the deal was announced, it has been embroiled in a web of murder and corruption allegations. Soon after the deal was concluded, translator and sometime model Altantuya Shaariibuu was found murdered in the Malaysian jungle. She had been rumored to be the lover of the then-defense minister and involved in discussions around securing a substantial commission from DCNS. In 2009, two police commanders were found guilty of the murder, one of whom claims he was ‘under orders’ from ‘important people’.30 It was later alleged that DCNS had made a payment of at least €114m to the company Perimekar, closely linked to the defense minister and Malaysia’s governing party.31 Making matters worse, when the submarines arrived there were such severe problems that the first submarine was declared ‘unfit for diving’,32 a crucial measure of success for any submarine. The problem: it had developed faults in two separate systems. Malaysia had to wait for DCNS to fix the problems before they could be safely deployed.

Wars can make you less secure in the long term

The third way in which defense spending can actually decrease security is when military spending funds wars that, despite their intentions, worsen a country’s security situation.

Nowhere is this clearer than in the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is arguable that the two largest US military engagements of the 21st century so far have actually left the United States and the world less secure than if they had never been undertaken. Not only did the conflicts cost trillions of dollars and cause hundreds of thousands of casualties, but they have contributed to an increase in terrorist activity and capabilities in areas well beyond the boundaries of the two states.33

The war in Afghanistan—the longest war in US history—is in one respect a response to the ‘blowback’ from US military interventions of the 1980s.34 The CIA spent hundreds of millions of dollars arming and training Afghan mujahidin forces to help them fight off the Soviet occupation of their country. A significant portion of this aid was diverted by Pakistani intelligence, which used it to support Islamic extremist groups that have engaged in terrorism in South Asia and beyond. Aid that did reach Afghanistan often ended up in the hands of foreign fighters and forces that had an anti-US orientation.35 Once the Soviet occupation had been repelled, and a nasty civil war was concluded, these groups turned their attention to attacking the United States and its interests. Following the civil war, many of them became part of the original cadre of Osama Bin Laden’s Al Qaida organization, which was hosted by the Taliban government in Afghanistan.36 The Taliban itself has received substantial support from Pakistani intelligence.37

As a result, when the United States invaded Afghanistan in October 2001 to root out Al Qaida, it was in part addressing a problem of its own making. And the mission of driving Al Qaida out of Afghanistan soon morphed into a large-scale counterinsurgency effort designed to defeat the Taliban and remake Afghanistan as a pro-US ‘democracy’ (or at least a pro-US regime, democratic or not). Fifteen years later the Taliban remains a major force in Afghanistan, the regime in Kabul is rife with corruption, and Al Qaida has entrenched itself in Pakistan. As we saw at the very beginning of this book with the case of Gerdec, Afghanistan has also become the site of spiraling defense corruption. This is what the United States and the world got for Washington and Europe’s investment in a trillion-dollar military undertaking in Afghanistan.

The case of Iraq is, of course, even more striking, in that it was without question a war of choice, and it has spawned a new generation of militant extremists, notably ISIS, who largely use military equipment supplied to the country by the US itself.

Military spending isn’t always intended to protect citizens

The fourth way in which defense spending can decrease the security of citizens is that in undemocratic states, military spending can make citizens less safe. Indeed, spending on one’s military in many cases does not mean protecting the country, but rather protecting the ruling elite from its people or discontented groups within the population, rather than protecting the people as a whole from external or internal threats. Even in more democratic, or partially democratic countries, the military may suppress legitimate dissent among citizens and marginalized groups.

There is strong data to show that military spending as a percentage of GDP is likely to be higher in countries with poor democratic records. The research group Freedom House provides an annual scoring of countries according to different levels of political and civil freedoms, with three broad classifications of ‘Free’, ‘Partially Free’ and ‘Not Free’. In 2013, amongst countries in the SIPRI Military Expenditure Database, sixty-five were classed as ‘Free’, fifty-four as ‘Partially Free’ and forty-eight as ‘Not Free’.38 Comparing ‘freedom’ with military spending reveals that the less free a country is, the more it tends to spend on the military.39

Saudi Arabian Defense Spending and the Maintenance of Dictatorship

Saudi Arabia became the world’s fourth largest military spender in 2013, at $67bn, and is currently the largest importer of weapons in the world. Its spending has increased by 118% since 2004 in real terms. At 9.3% of GDP, Saudi Arabia has the second highest military burden of countries for which SIPRI had data in 2013, after neighboring Oman. Moreover, the official figure probably excludes significant off-budget spending on arms imports, which in some cases are purchased directly with oil revenues, or indeed in oil for arms swaps such as the Al Yamamah deals with the UK in the 1980s and 1990s.

While Saudi Arabia has significant tensions with its neighbor across the Gulf, Iran, the latter is a far weaker military power with little ability to launch a successful attack on Saudi Arabia and other Gulf nations. Years of sanctions on Iran have increased the costs of acquiring and maintaining weapons systems, and it often has to make do with running older systems that would be massively outgunned by a fraction of Saudi power. Indeed, the Centre for Strategic and International Studies stated in 2015 that ‘Iran has been unable to compete in terms of both investment and access to advanced foreign systems’ compared to other Middle East nations.40 It also outlined how Iran’s navy and air force were both reliant on heavily outdated and largely obsolescent equipment they can barely maintain.

Instead, the primary purpose of Saudi Arabia’s armed forces over the years has been regime protection—ensuring the continuing rule of the House of Saud that has treated the nation as its family fiefdom since coming to power in 1932, ruthlessly suppressing all dissent. The Saudi regime has one of the worst human rights records in the world. It maintains several parallel armed forces (such as the National Guard as well as the regular army) to ensure that no single force can become too powerful and itself pose a threat to the ruling family.

Saudi Arabia’s major weapons systems are not directly utilized for domestic repression, of course. But corruption has been a standing feature of arms purchases by Saudi Arabia from foreign suppliers, and the vast military budget—with barely any democratic controls or oversight—provides a massive opportunity for self-enrichment by elites. And this in turn enables the protection of the ruling elite through patronage. By distributing wealth through positions and contracts for families and friends, not just its armaments, the house of Saud sustains its power.

Using the military to solve the world’s security issues isn’t always the best bet

The fifth way that military spending can decrease security is that massive military expenditure can increase the tendency to seek military solutions to non-military problems. One example of this has been the decades-long US ‘war on drugs’ which has been used to justify aid to death squads and repressive regimes abroad and mass surveillance and incarceration at home. For example, the multi-billion US ‘Plan Colombia’, designed to help the Colombian government dismantle the drug cartels there, included aid to a corrupt military that regularly abused human rights and aerial application of pesticides in large parts of the country. To the extent that Plan Colombia helped undermine the drug cartels there, the drug trade was merely displaced to Central American countries like Honduras and Mexico, where high levels of violence by drug gangs have become the norm. Other suggested approaches, like reducing drug demand in the US by expanding treatment programs and providing alternative forms of employment in impoverished areas, have received only modest resources relative to the sums spent on military methods of fighting drugs.41

Another example of militarized approaches to non-military problems was the international approach to tackling Ebola. Global public health was identified as a threat to international peace and security by the UN Security Council in 2000, following a US National Intelligence Council assessment.42 However, the risk that pandemic diseases—HIV/AIDS, influenza and tropical diseases such as Ebola—might lead to state crisis in developing countries and catastrophic disruptions to international travel and world trade was not matched by commensurate spending. Certainly, international donors increased their assistance to health fourfold in the following decade, and in 2012 $28bn was spent annually on global assistance programs for public health, with the US government as the largest contributor.43 But this amount pales into insignificance compared to the spending on weapons. And in the hard-hit country of Liberia, the US prioritized rebuilding the country’s armed forces over rebuilding its health services.

This spending differential meant that when the Ebola epidemic struck West Africa in 2014, those countries, the United Nations and the world were ill-prepared. In September, President Obama announced Operation United Assistance, and dispatched the 101st Airborne Division to Liberia. He said:

Our forces are going to bring their expertise in command and control, in logistics, in engineering. And our Department of Defense is better at that, our armed services are better at that, than any organization on Earth. We’re going to create an air bridge to get health workers and medical supplies into West Africa faster.44

His words are surely true—after all, the largest defense budget in the world should buy some impressive logistics—but a military-led response proved cost-inefficient and ineffective. The operation cost $330m over six months,45 compared to the approved budget of the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response of $49.9m.46 Unfortunately, many of the shelters that the US built took too long to erect: in January 2015, the Washington Post reported that the shelters were put up just as the Ebola infection began to abate. Some shelters have not seen a single Ebola patient. The Liberian government’s chairman for Ebola management, Moses Massaquoi, commented that ‘if they had been built when we needed them, it wouldn’t have been too much. But they were too late’.47

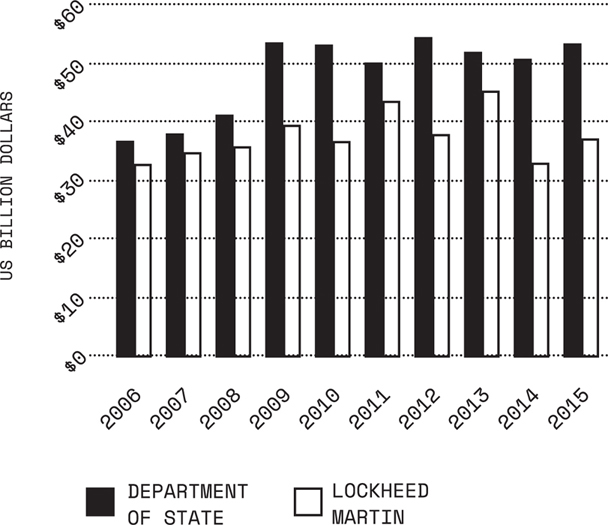

Large amounts of military spending can also draw funds away from other non-military ways of increasing security: effective diplomacy and cooperative action. In the US, the Pentagon budget is roughly fourteen times the budget of the US State Department. This is truly remarkable: in its relationship with the outside world, the US devotes 1,400% more to projecting military power than it does on building alliances and finding non-military solutions to conflicts. In fact, the State Department has, over the past decade, received roughly similar levels of funding as the DoD’s number one contractor, Lockheed Martin (see Figure 1.6). As for peacekeeping, the US contribution to UN peacekeeping efforts is less than 0.5% of what it spends on military activities. If the United States devoted a tiny fraction of what it spends on its own military to support the cost of the United Nations and multilateral peacekeeping, a robust international capability could be on call to enforce peace agreements, protect potential victims of repression and genocide, and separate warring parties.48

Figure 1.6 US State Department budget vs. Lockheed Martin federal contracts ($bn)

Source: Extrapolated from Susan B. Epstein, Marian L. Lawson, and Alex Tiersky, “State, Foreign Operations, and Related Programs: FY2016 Budget and Appropriations,” Congressional Research Service, November 5, 2015, Table 2, p. 5, accessed June 1, 2016, https://www.fas.org/sgp/crs/row/R43901.pdf.

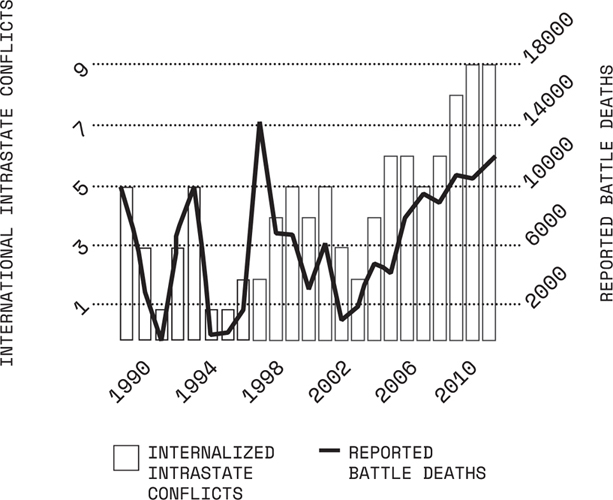

There is, of course, a counter-argument: if states spend on their military, it enables them to get involved in disputes that threaten human rights or democracy, shutting down the worst abuses and ending wars. Unfortunately, there is strong data showing that the involvement of more than two parties (where outside countries become involved) in a conflict tends to increase the length and deadliness of wars: just look at Figure 1.7. Note that this is generally not true of conflicts that include the involvement of the UN or other peacekeeping efforts; it is when international parties join in on a military footing outside of multilateral institutions, either directly or through supplying weapons and supplies, that things get messy. On this issue, there seems to be an increasing and concerning trend: in 2013, 27% of active conflicts were internationalized.

Figure 1.7 Internationalized intrastate conflicts and battle deaths, 1989‒2011

Military intervention to support one side in a civil war is associated with high death tolls—nearly 1500 per conflict in an average year. The devastating effect is not limited to intervention by majoy powerts. The high death toll for this type of conflict in 1997, for example, was caused by conflicts in the Democratic Republic of Congo, both of which saw interventions by troops from neighboring countries.

Source: Human Security Report Project, Human Security Report 2013: The Decline in Global Violence: Evidence, Explanation, and Contestation (Vancouver: Human Security Press, 2013), 90.

Indeed, resolving conflicts tends to be easier when there are fewer actors involved—the more parties to a conflict, the longer violence tends to last and the more people tend to be killed.49 One of today’s bloodiest conflicts, Syria, is undoubtedly longer, more lethal and more intractable because of the many outside countries that have pursued the goal of supporting one side or another in the attempt to militarily conclude the conflict, rather than providing offices for mediating it or powerful incentives to end it.50

Is Massive Military Spending the Best Way to Tackle Terrorism?

In a large number of Western countries—the US and UK in particular—the threat of transnational terrorism is frequently cited as a primary reason for current levels of defense spending. Indeed, the reiteration that the West is at ‘war’ against terrorism only serves to reinforce the idea that military operations are the best way of tackling this threat. In this instance, the logical leap is easy to see: spend more money on defense and be more secure against terrorism.

In the US, this thinking has led to the military receiving the vast majority of counterterrorism funding. Between 2001 and 2007, Congress approved a total of $609bn for a range of counterterrorism activities. Of this, 90% went to the Department of Defense. By comparison, the US Department of State and USAID received a total of only $40bn over the same period.51

But the idea that there is a military solution to terrorism has been put into serious doubt by an influential 2008 study by the US-based RAND Corporation—a think-tank esteemed by conservatives.52 The study reviewed the life-cycles of 648 terrorist groups from 1968 to 2006, identifying the ways in which these groups ended. It found that in 43% of cases, terrorist groups ceased to exist because they were successfully integrated into the formal political process. In 40% of cases, the groups disappeared because of successful policing efforts. A further 10% of terrorist groups stopped their military activities because they achieved their main aim. And, most importantly for this discussion, only 7% of terrorist groups were snuffed out as a result of military campaigns.53

The statistics generated from the study had clear implications: using the military to win the ‘war on terror’ is simply not going to work. More to the point, it is likely to be counter-productive, fueling resentment and undermining long-term regional goals. As the Jones and Libicki note:

Our analysis suggests that there is no battlefield solution to terrorism. Military force usually has the opposite effect of what is intended: it is often over-used, alienates the local population by its heavy-handed nature, and provides a window of opportunity for terrorist-group recruitment.54

Jonathan Powell, who served as the British government’s negotiator for the peace talks in Northern Ireland, makes similar points.55 Indeed, having their own experience of domestic terrorism and the bloody end to imperial and minority rule in colonies such as Malaya, Kenya and Rhodesia, Britain’s military chiefs thought it unwise for the US to declare a ‘war’ on terrorists. Powell notes that no group designated as a terrorist, which draws support from a popular constituency, has been defeated by military means alone.

Africa’s leaders have their own particular perspective on terrorism. Many, including the current leaders of South Africa and Namibia, were themselves branded as ‘terrorists’ by their former white rulers. In recent times, the African Union has taken a lead in putting together regional military coalitions for combat operations against militant extremists, notably Al-Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria. But in the 2015 African Union annual retreat for conflict mediators, on the theme of Terrorism, Mediation and Armed Groups, African leaders expressed a consensus view that military efforts should be conducted in support of a political settlement to a conflict involving terrorist groups.56 In short, armed force should be a component of a broader political strategy, reversing the ranking too often seen in the ‘war on terror’ whereby diplomats serve as ‘wingmen’ to generals.57

RETHINKING SECURITY

In this chapter we have tackled the issue of security in a very traditional sense, namely as a measure of protection against military violence. This is, arguably, the way that many people understand the concept of security: keeping the country safe from invasion or violence. But there is a strong and emerging trend towards considering security in a much broader—and much more useful—way.

Driving this thinking is the adoption of a paradigm that goes by the name of ‘human security’. Human security is defined by the United Nations as ‘the right of all people to live in freedom and dignity, free from poverty and despair’. Underpinning this is the recognition that ‘all individuals, in particular vulnerable people, are entitled to freedom from fear and freedom from want, with an equal opportunity to enjoy all their rights and fully develop their human potential’.58

When security is thought about in this way—and it is hard to argue that a population that is chronically malnourished is not at risk—the type of threats that need to be addressed changes drastically. Instead of just focusing on threats from war or conflict, human security requires us to look at all the various risks that are faced in the world today that undermine human dignity, drive poverty and put billions of people in a constant state of emergency of survival. Some of these risks include access to clean water, food security, climate change, health pandemics, violent multinational organized crime and repressive states that use their monopoly of violence to terrorize their own populations.

There is little doubt that, when considered in this light, the world suffers a serious human security deficit. Global disease, poverty and hunger, for example, devastate lives in many parts of the world. It is estimated that 1.5 million children under five die each year of vaccine-preventable diseases,59 while 3.1 million children a year die from malnutrition.60

Some national leaders recognize this. An interesting example is Ethiopia, long one of the poorest and most conflict-ridden countries in the world. Following a devastating border war with neighboring Eritrea in 1998‒2000, and facing security threats from its other neighbors, Somalia and Sudan, the Ethiopian government published its national security policy white paper in 2002.61 Decrying what it called ‘jingoism with an empty stomach’, Ethiopia put economic development at the centre of its national security plan, with military spending (capped at 2% of GDP but in practice lower) as subordinate to that goal.

Meanwhile, the world stands on the brink of one of the biggest global catastrophes in human history, in the form of climate change. With no substantial change in the way things are done around the world, and no effort made to tackle global greenhouse gas emissions, it is predicted that the earth’s temperature will rise by 3.7 to 4.8 degrees Celsius by 2100.62 The consequences of this would be devastating, threatening human—and national and international—security in numerous ways:

•Increased drought in many parts of the world, leading to severe water shortages.

•Greatly reduced global agricultural yields from increased heat and reduced rainfall, as global food demand increases.

•A major spread of tropical diseases such as malaria to new parts of the world, potentially leading to millions of additional deaths.

•A major increase in the prevalence and severity of natural disasters such as hurricanes and flooding, with the potential to devastate low-lying and coastal regions, a phenomenon that is already observable today.

•In the extreme, low-lying areas and small island states becoming completely uninhabitable.

•Vast refugee flows resulting from the above developments.

•Increased internal and international tensions over water resources and increasingly scarce fertile land.

•Mass extinction of species and loss of biodiversity, with severe consequences for humans through the food chain.63

But even rises of less than 2 degrees Celsius, a level considered increasingly difficult to achieve, would lead to many severe consequences of the type listed above; the more action is taken to reduce emissions, the lower the likely temperature rise, and the less probable the most dangerous impacts become.

Where, you might ask, does military spending fit into this?

In two key ways. First, military expenditure is massive, and fails to substantially tackle any of these major threats to human security. If only a fraction of military spending was focused on broader human security goals, the improvement in the security profile of billions of people around the world would be tremendous.

The second way in which spending on weapons contributes to human security should also be obvious: the goals of freedom from want and fear are most likely to be achieved in democratic states that are accountable to their populations. But, as we’ve discussed in detail above, huge amounts of global military spending is directed towards maintaining dictatorships or repressive regimes. This is not just a problem of the developing world. The majority of military purchases by repressive regimes are from the world’s biggest arms dealers: the permanent members of the UN Security Council. And even in democracies, military spending that is tainted by corruption poses a major threat to good governance, and can, in the worst case scenarios, create the mechanisms by which democracy gets replaced by oligarchy and repression (this is discussed in detail in Myth 5).

Considering this, perhaps it is time to recognize one powerful fact: even a small reduction in defense spending, one that sees resources properly devoted to the human security dangers faced by the majority of the world’s population, could actually make the world safer, healthier, more prosperous and more secure.