MYTH 4

THE DEFENSE INDUSTRY IS A KEY CONTRIBUTOR TO NATIONAL ECONOMIES

As we’ve seen in Myth 2, one of the key justifications for military spending is the impact it has on the economy. This argument is trotted out whenever there is even the vaguest threat of cuts in defense spending, which usually draws a widespread gnashing of teeth and dire predictions of massive unemployment leading to national calamity. For politicians who want to put their own fingers into the pork barrel and appear strong on defense, plumping up the vital role that defense plays in the economy of arms producers is a no-brainer.

Just one problem: there is very little evidence that military spending does benefit the economy, and indeed rather more evidence that its effect is actually harmful. Far from driving the economy, national arms industries typically rely on massive welfare and subsidies from their parent governments to stay afloat. The arms business does create jobs—but, because of the massive subsidies involved, far fewer jobs and at greater expense than alternative investments. Rather than driving innovation, the arms business mostly free-rides on civilian innovation, taking existing technologies and cobbling them together. And since it competes for talent and resources with other industries, in some ways the business actually slows down civilian scientific and technological advancement.

SIZE MATTERS

Despite the triumphalist advertising of the defense industry, it is relatively small as a share of total industry or manufacturing outside of the United States. In the UK, which has the second largest defense industry in the world, the total sales of manufactured military products was £13.1bn in 2013.1 This may seem like a large number, but it is nothing compared to the food and drink sector, for example, which added £21.5bn to the UK economy and has a turnover of £81.8bn.2 Indeed, the total value of sales of products manufactured in the UK in the same year was £354.5bn.3 Sales from defense manufacturing thus only constitutes 3.8% of total manufacturing sales in the country. And compared to total GDP—£1.8trn in 2013—it is absolutely miniscule. And all this despite the Ministry of Defense receiving roughly 6% of all UK government spending over the last few years.4

In Europe as a whole, the amount contributed by defense is even more marginal. According to the European Aeronautics and Defense Association, the total turnover for defense companies in 2012 was €95bn in twenty European countries (seventeen European Union members, including the UK, as well as Norway, Switzerland and Turkey).5 This is remarkably small compared against the €6.4trn in turnover recorded for manufacturing in the European Union in the same year.6 Exact figures for Chinese defense manufacturing are hard to come by, but, based on China’s considerably smaller defense spend and much smaller defense export market compared to other members of the UN Security Council, is likely to be only a tiny fraction of China’s $1.6trn manufacturing output.

There is, of course, one exception: the United States. The US is different because its expenditures on defense and the value of its weapons exports are far higher than for any other nation. But given the size of the US economy, it remains the case that arms production and trade account for a relatively small share of total economic activity. In 2010, when total Pentagon spending (both its base budget and the separate account for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan) topped $700bn and reached its highest levels since World War II, it was still only about 4.5% of USGDP.7 And in 2011, when US arms trade agreements were estimated at a record $66.3bn by the Congressional Research Service,8 they paled in comparison to the $1.49trn in goods and $627bn in services exported in the same year (for a total of $2.12trn); indeed, defense exports only constituted 4% of total US exports.9

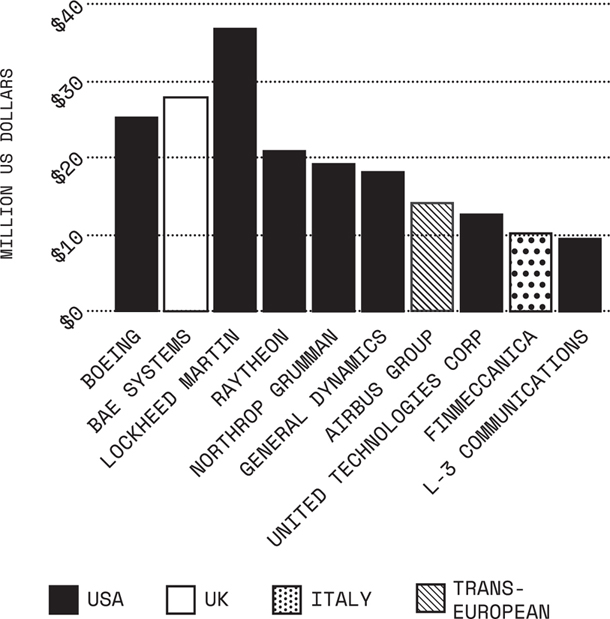

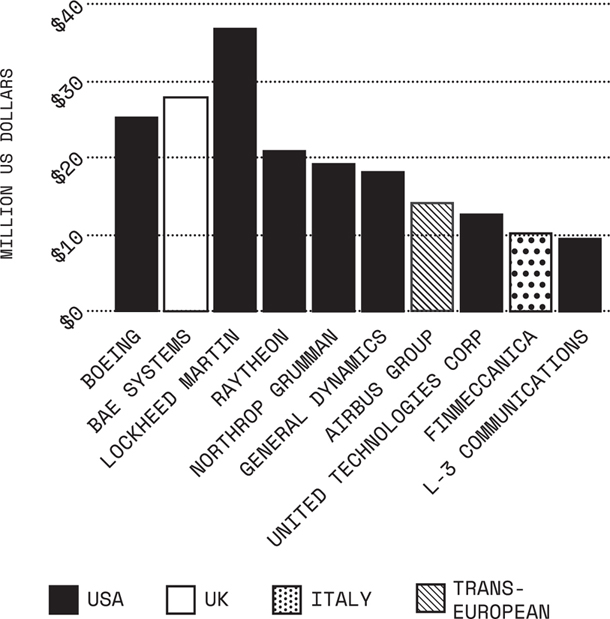

Unsurprisingly, it is the US that boasts the largest defense companies in the world. As Figure 4.1 shows, only one non-US company (BAE Systems, which in any event has extensive US operations which usually account for over 40% of its revenues) is in the top five global arms sellers.

And this is why size matters: it makes the economics of the international defense industry incredibly strange. If the arms trade worked like any other industry—making fridges, say—there simply would not be any non-US manufacturers. This is because the US local demand gives it huge advantages in economies of scale: if you’re already producing 1,000 tanks for your own military, it’s much easier and cheaper, per unit, to add an extra 200 to sell to your allies than it is to design a tank from scratch if your military only needs 200 for itself.

Other defense manufacturers—the largest of which are all in Europe—have to find other means by which to sell their products, as their lack of economies of scale means that they struggle to compete purely on product and price. They tend to seek economies of scale in either pooling resources into single products (the Eurofighter) or by engaging in extensive exports. But if they can’t compete on price and product, they have to start thinking more creatively, offering more than just weapons.

Figure 4.1 Companies with largest arms sales, 2014 (US$m)

Source: Extrapolated from Aude Fleurant, Sam Perlo-Freeman, Pieter D. Wezeman, Siemon T. Wezeman and Noel Kelly, “The SIPRI Top 100 Arms Producing Companies, 2014,” SIPRI Fact Sheet, December 2015, Table 1 (p. 3), accessed June 2, 2016, http://books.sipri.org/files/FS/SIPRIFS1512.pdf.

This is why the European defense industry has become expert at offering two sorts of inducements: economic offsets (discussed briefly in Myth 2 and in more detail later) and bribes. Indeed, as we will consider in the following chapter, it is the non-US defense industry that is most often involved in corruption, without which it arguably could not compete. That is not to say that there aren’t major problems with US defense companies exerting influence on policy via lobbyists and Washington politicians in what has been described as ‘systemic legal bribery’, but it is clear that the most outrageous outright bribery tends to be undertaken by players outside of the US. In a dysfunctional industry, dysfunctional behavior becomes the norm.

Thus, when the defense industry starts to speak darkly about national economic collapse at the threat of defense cuts, we need to bear two things in mind. First, it simply is not true that the defense industry is central to the global economy and that cuts, therefore, lead to economic Armageddon. Second, perhaps it may not be the best idea to pour money into a dysfunctional industry that is not very economically efficient and is structured in such a way as to almost demand widespread corruption.

THE BIG PICTURE: DEFENSE SPENDING AND ECONOMIC GROWTH

If defenders of the industry cannot convince you that defense spending staves off industrial catastrophe, they can always argue that, regardless of size, defense spending nevertheless positively contributes to national economies by driving economic growth. Again, it is an argument that has very little data to support it.

Over the last thirty years, defense economists have tracked the correlation between defense spending and economic growth in multiple countries. While the details are still hotly debated in the pages of academic journals, the overall results show that instead of feeding growth, defense spending has been shown to have an insignificant or negative impact on growth. In countries where there is a marked negative impact on growth, they are said to be laboring under what is known as a ‘defense burden’.

Analysts of defense expenditure and economic growth have looked into numerous channels through which defense expenditure can have an impact on economic performance.10 Among the key factors considered are:

•Labor: how military spending can both lead to the training of advancement of military recruits, but may suck up educated and technically proficient employees from the civilian sector.

•Capital: how military investment can create industrial output, but can also ‘crowd out’ investment in the civilian industries, hampering growth.

•Technology: how arms production and imports can increase the technological base of an economy, but may create an advanced technological sector delinked from the rest of the economy and reliant on government support.

•Socio-political: how military spending can have positive spin-offs by introducing a modernizing influence and reducing internal conflict, but may end up supporting dictatorial and corrupt regimes that, as a whole, stifle growth.

•Debt: how military spending in especially developing economies is funded by large public debt, which can constrain the raising of capital for civilian industries or limit state spending on other more productive areas of the economy.11

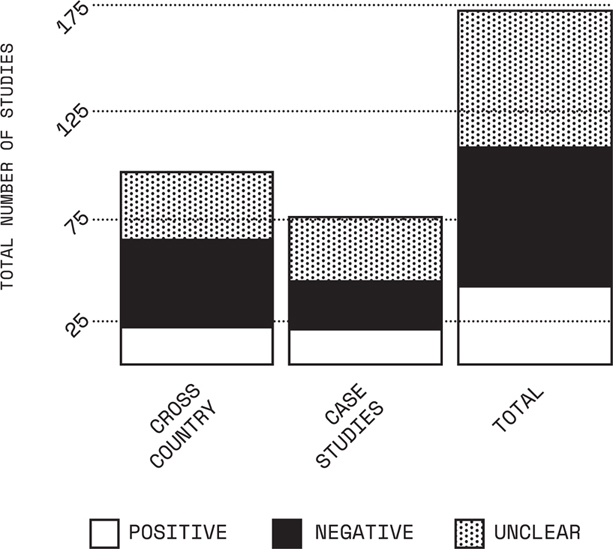

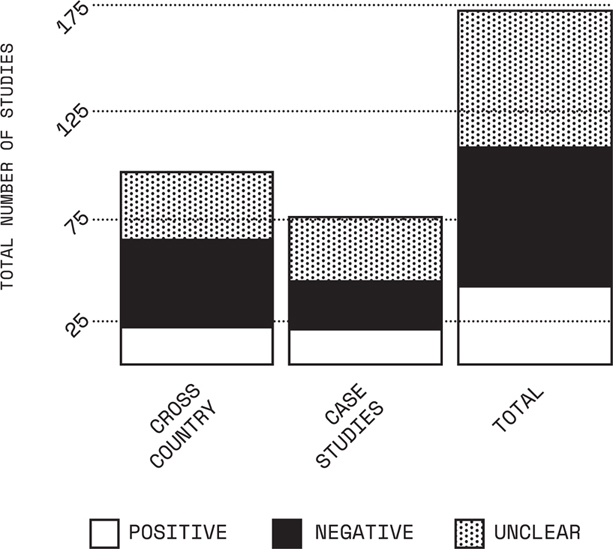

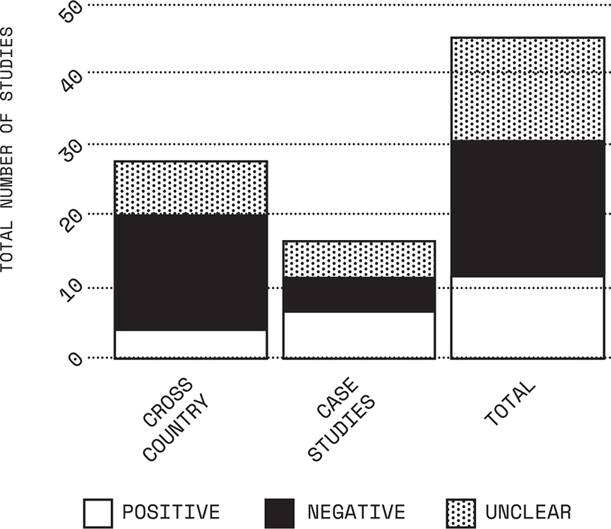

In one vital 2013 study by the defense economists Professors John Paul Dunne and Nan Tian, the entirety of the existing literature (close to 170 papers) was reviewed. The literature covered a wide range of countries, from developed to developing economies. They found that, in the majority of cases, the studies undertaken had suggested an overwhelming ambiguous or negative impact on growth, as Figure 4.2 shows.

These data, too, need to be put into context. In almost all cases where there was a positive result, the analysts had used a simple ‘supply-side’ equation, in which they looked at the amounts of money going into the economy and the economic activity associated with it. This, Dunne argues, is unsurprising as these models are ‘inherently structured to find such a result’. When studies include a ‘demand-side’ calculation, such as the impact of military spending on crowding out other investments in the economy, the results are almost always negative or ambiguous.12

Figure 4.2 Studies on economic impact of defense spending

Studies undertaken 1973–2006

Studies undertaken 2007–early 2013

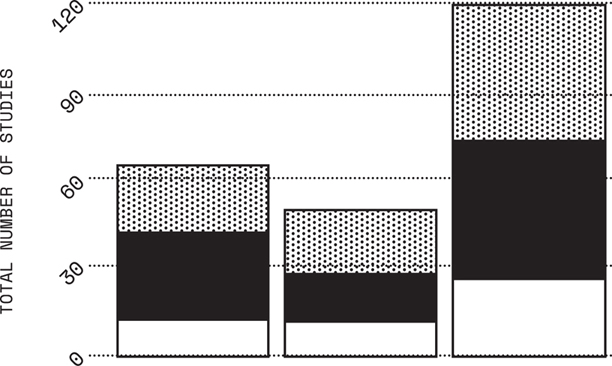

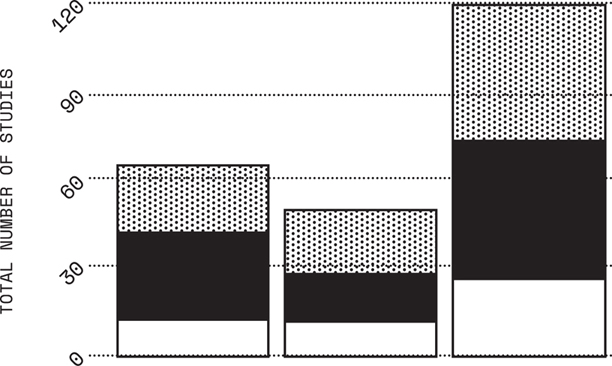

Figure 4.3 Studies on economic impact of defense spending - comparison of studies published pre- and post-2007

Dunne and Tan make one additional point: the studies that were conducted using Cold War data were more likely to produce positive results. New studies that focus on post-Cold War economics tend to show more markedly negative results. In simpler terms, since the end of the Cold War in particular, the data has shown that military spending has a downward impact on the economy. This is clear from the second figure of data included in Dunne and Tan’s survey (Figure 4.3), which shows that studies undertaken since 2007, using more post-Cold War data, have produced clearer negative results.

Reviewing their results, Dunne and Tan were emphatic: ‘What does seem increasingly clear is that military expenditure does in general come at an economic cost … The more recent literature is moving towards a commonly accepted, if not consensus, view: Military expenditure has a negative effect on economic growth.’13

WHAT ABOUT JOBS?

As we saw in the previous chapter, one of the primary ways in which arms sales and military spending are sold to the public is that they are said to produce millions of jobs in the producing countries. And this is broadly true. The world spends over a trillion dollars on defense every year, and with such a huge outflow of funds, you’re bound to create jobs. The problem is defense spending creates far fewer jobs than virtually any other activity.

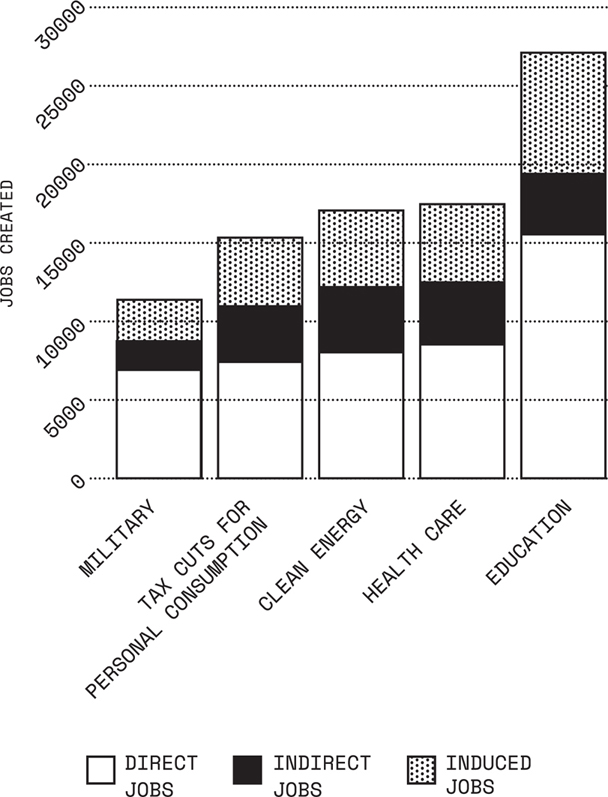

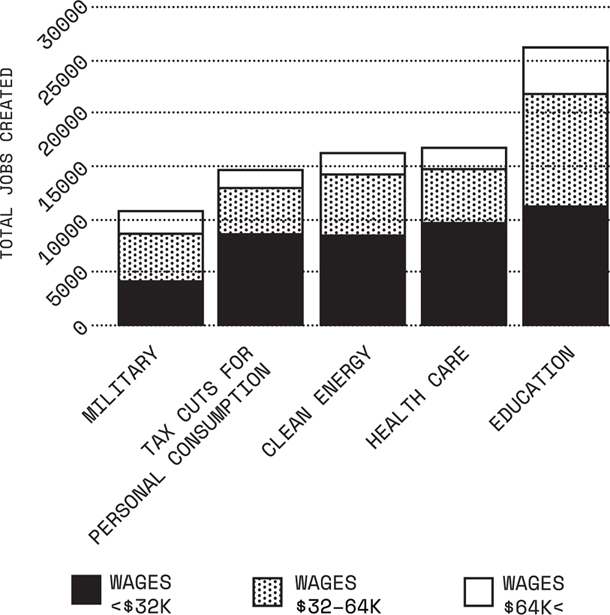

In 2011, researchers from the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts reviewed the available data on the impact of defense spending on job creation in the US. This was compared against the estimated cost of creating jobs through spending on four non-military alternatives: health care, education, the green economy and tax cuts.14 The results were clear.

First, it should be mentioned that it is undoubted that military spending in the US creates a ton of jobs. In total, the authors estimated that Pentagon spending in 2010 (at $690bn) created nearly 6 million jobs, both within the military and in related civilian sectors of the economy.15

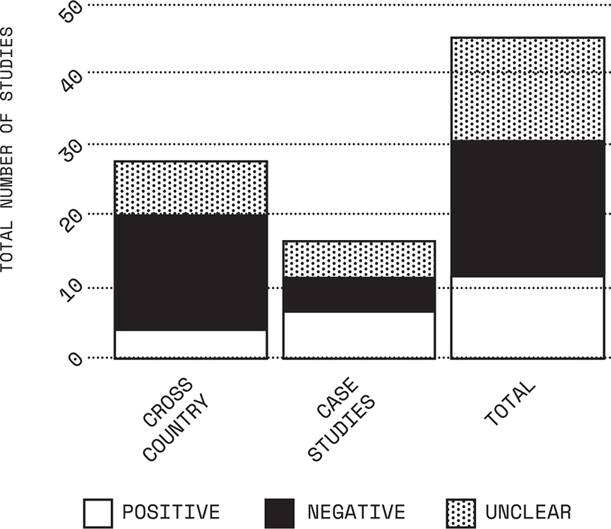

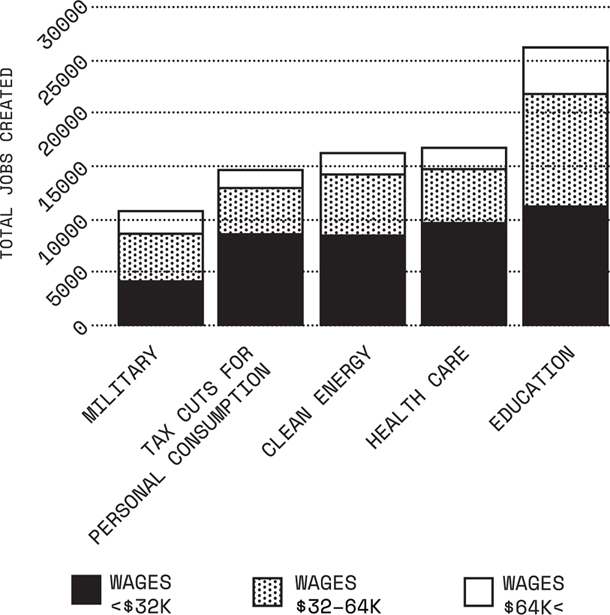

But the rate of job creation for this outlay is, in reality, rather paltry. Working back from the statistics available, the researchers calculated that spending on defense creates 11,200 jobs for every $1bn spent. This was a lower number of jobs per $1bn than any other alternative. Cutting taxes by the same amount, it was found, would create 15,100 jobs per $1bn (through consumer consumption); clean energy would create 16,800 jobs; healthcare would create 17,200 jobs; and spending on education would create 26,700 jobs per $1bn, a full 138% more than spending on defense achieved.16 Figures 4.4 and 4.5 show this clearly.

What is even more remarkable about these figures is that, despite each job costing less than alternatives, the quality of jobs, at least judged against remuneration, would be roughly the same as those created by military spending. Or, in other words, other sectors would not create more jobs per $1bn because those jobs are worse paid.17 Instead, what emerges from the data is that defense jobs cost far more than other sectors not because of different wage structures, but because a good portion of the spending on defense goes to military employees (rather than just civilian contractors), and these military employees are offered extensive benefits. Taking this into account, it emerges, quite clearly, that spending on other sectors produces a similar proportion of low, medium and high wage jobs.18

Why, you may ask, does defense spending produce so many fewer jobs than other sectors? For this, the researchers pointed to three key variables. The first is the labor intensity of economic activity, or, in simpler terms, how much of the money being spent is being used to hire people rather than on machinery, buildings, energy and other inputs. The researchers found that defense manufacture, which is highly mechanized and requires substantial industrial inputs, had a labor intensity much lower than other sectors, but particularly in relation to education, where much more of the money spent goes to paying teachers’ salaries.19

Figure 4.5 Distribution of jobs by wage levels in alternative US economic sectors: jobs created through $1bn in spending within each sector

The second concerns domestic content, or how much of the money being spent goes towards buying products in the local economy. This is of particular concern when it comes to creating indirect jobs, or putting money in the broader economy. The researchers found that US military personnel, partially due to their overseas postings but also due to the import-heavy nature of the industry, spend only 43% of their income buying US products. By comparison, the average US citizen spends 78% of their income on US products.20

The third point, as we hinted above, relates to compensation per worker. It should be obvious that in industries where pay is low, more jobs are created per dollar spent. And, because of the high levels of benefits granted to military personnel, the average amount each employee costs is far more than in other industries. This is not to suggest that military personnel do not deserve benefits—nobody will begrudge a serviceman access to veteran medical cover. But it does suggest that military jobs come with an added cost that generally reduces the number of jobs that can be created per dollar spent.

What’s even more remarkable about research that has been done so far is the rather counter-intuitive finding that even defense exports have a deflationary impact on employment. This is unexpected as one would anticipate that simply selling weapons to a willing buyer would be pure profit. However, studies in the UK suggest the opposite. In one study, for example, it was found that arms exports were made possible only through the use of public funds via enormous subsidies, subsidies that reached £936m at the highest estimate.21 These subsidies amounted to up to £14,000 per job created from export sales, which are supposed to be pure profit, and do not take into account the fact that the export sales are only possible after the British state has already invested heavily in the companies through their own procurement.22

Another key study from the early 2000s found that halving defense exports from the UK would actually create jobs, not lead to their loss. This is for two primary reasons: the levels of subsidies and taxpayer funds that go into securing the sales would be freed up to be spent elsewhere, and the fact that defense export sales tend to suck up rare skills from the civilian economy. The study found that, although 49,000 jobs would be lost by the halving of defense exports, it would be more than made up for through the creation of 67,000 jobs over five years elsewhere in the economy as skill shortages eased and the industrial base diversified.23

BUT THEY INVENTED THE INTERNET!

The last trope usually wheeled out by those that oppose any cuts in defense is the supposedly vital role that defense manufacturers play in innovation and high-tech industrial development.

And this argument was true. Sort of. For a while. During the Cold War, vast sums of money were dedicated to military research and development, which fed the development of a range of civilian applications.24 Starting with the Manhattan Project, which kick-started the development of nuclear energy, the Cold War was a time when military research was at the cutting edge of science. Where it led to civilian technologies—duct tape, for example, was designed as a means of securing the bottom ends of shaky ammunition shells—it should be recognized. Many of these research gains, however, relied equally on prior civilian research, and, most importantly, the civilian market to turn specialist and obscure inventions into something that civilians would find useful: exactly what happened with regard to the internet.

But what should also be recognized is that the R&D that was undertaken also led to enormous funds being used on military inventions that were frankly ludicrous, and never worked, creating what Mary Kaldor has called a ‘baroque arsenal’.25 Kaldor argued that the fact that defense spending was so privileged—research that is undertaken is completely unrelated to any potential civilian or market application—led to an environment where even the most insane ideas would get funding. In addition, the closeted research environment meant that arms companies spent billions perfecting weapons, even when those tiny gains had no noticeable impact on combat performance.

Crazy Money for Crazy Ideas: Star Wars and Its Sequel

Perhaps the most famous example of Cold War tech hubris was the proposed development of Star Wars (actually named the Strategic Defense Initiative), the US’ ill-fated attempt to build a system that could shoot down incoming nuclear weapons with lasers. Over the course of its nearly ten-year development, the US spent $60bn on research and testing: double the amount that was spent on the Manhattan Project.26 This despite the fact that most scientists at the time were firmly of the opinion that intercepting tiny missiles, sent in a balloon of decoys at thousands of kilometers an hour, was an almost insurmountable task. Unsurprisingly, when the program was quietly scrapped in the early 1990s, not been a single mirror or laser system had been developed.27

Some tests were conducted that replaced the lasers with guided missiles, but even these results were pretty poor. The two successful tests in 1984 and 1991 (the only two successful intercepts out of multiple attempts) were only achieved when ‘real world variables’ were removed from the equation. Amongst the concessions made were the decision to set the target on a pre-determined flight path, which was to be intercepted by a missile on its own pre-determined flight path; a Global Positioning Satellite receiver was placed on the target to help guidance; and the decoys that were released were of such different thermal temperatures that targeting the real threat was a doddle. Of course, no real nuclear weapon flying towards the US at thousands of kilometers an hour would ever be so polite.28

What often gets left out of these discussions is an intriguing counter-factual: isn’t it possible that the military’s involvement in technological development led to products that were actually worse for civilian use than if they had developed in isolation? One example of this is the military role in developing airplanes, which was given a major push by World War I. As the defense economist Jurgen Brauer notes:

Since the end of the Cold War, the role of defense in cutting-edge scientific development has been hugely curtailed. This has largely been driven by the decision that was taken in 1994 by Secretary of Defense William J. Perry, which was set out in an obscure but vital document now known as the ‘Perry Memo’.30 The memo marked a sea-change in US defense procurement and production: it stated that, as far as was practically possible, the US should integrate commercial technology into new defense articles. ‘To meet future needs’, the memo intoned, ‘the Department of Defense must increase access to commercial state-of-the-art technology and must facilitate the adoption by its suppliers of business process characteristics of world class suppliers.’31 Doing so, it was hoped, would help defense suppliers leverage the booming developments in civilian innovation, particularly around information technology.

This has led to the widespread adoption of what is known by the acronym COTS, or commercial-off-the-shelf technology. This takes place when defense products simply integrate the cutting-edge developments that have been proceeding apace in the civilian technology market. The upside of this approach has been a general improvement in the performance of military hardware and a substantial reduction in the cost of producing systems. One such example of this is the Acoustic Rapid COTS Insertion Program. This program was used to improve the US Navy’s ability to detect enemies at sea (it had, by the early 1990s, lost its ‘acoustic dominance’). This was resolved by the use of a number of commercial systems, including Intel processors to crunch data, which would have cost billions for the navy to produce itself. The result was a tenfold increase in the efficiency of the detection system and a full 86% reduction in the cost of operation.32

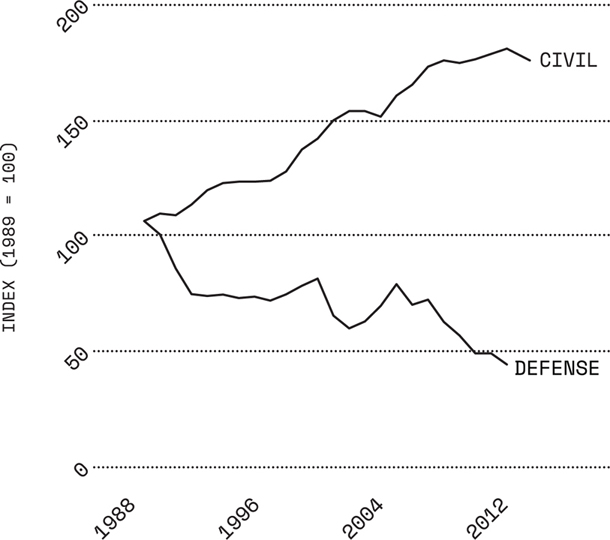

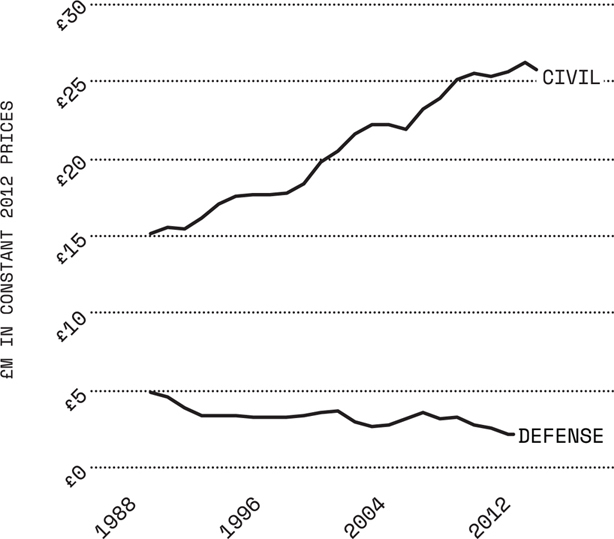

This is generally good news for taxpayers who don’t want to pay over the odds for weapons. But it also means that military research and development has dropped away radically, and its importance far outstripped by civilian efforts. In the UK, for example, military R&D dropped by nearly 60% between 1989 and 2010, while civilian R&D increased by nearly 70%,33 as Figure 4.6 shows.

While the index analysis in Figure 4.6 gives a good sense of how defense R&D funding has dropped precipitously since 1989 compared to civilian R&D, it does not give a sense of just how much larger, in absolute terms, civilian R&D is compared to defense R&D; and how much defense R&D has reduced in absolute numbers over the same period. As Figure 4.7 shows, defense spending on R&D fell from £4.7bn in 1989 and 1990 (2012 prices) to a rather substantially less impressive £1.8bn in 2012. By comparison, civilian R&D increased from a much larger £14.9bn in 1989 to £25.2bn in 2012. In simpler terms, defense R&D spending used to make up 23.9% of all R&D funding in the UK in 1989; as of 2012, this had fallen to a paltry 6% of total R&D spending.

In the US, the proportion of military R&D compared to civilian research has also been dropping consistently over the last thirty years. In 1985, at its peak, military research and development constituted 31.1% of all research in the US. By 2003, this had dropped to 16.6%. In other countries it was even more marked: in 1981, military research accounted for 9.3% of all R&D in the OECD countries; it had dropped to 3% by 2002.34 These figures have been remarkably stable since then, despite the massive increase in global defense spending since 9/11.

What is particularly striking about this is that defense continues to receive the largest whack of federal R&D funding (in 2009, $68.2bn, or a full 50% of US government-sponsored R&D was spent on defense research35); even with this major government support, defense has lagged far behind civilian innovation.

As it currently stands, the contribution of military research and development (almost all, it should be noted, driven by public grants, particularly in the US) is rather small in global terms. In 2010, the UK’s Department for Innovation and Skills released a scorecard of global research investment. It found that the amount spent by aerospace and defense companies on research and development globally in 2009 was £12.918bn, a mere 3.7% of the $344bn spent in total on research and development by the top 1,000 research and development companies around the world.36 Indeed, as of 2013, of the top twenty-five global research and development companies, not a single one was an arms manufacturer. The only defense firm in the top fifty was the European conglomerate EADS (it placed 30th),37 and its position was undoubtedly established partly because it includes the massive civilian aerospace company Airbus.

Did the Military Invent the Internet?

When you mention innovation and the defense trade, the first response you’ll get is almost always: did you know that the military invented the internet? But, of course, as with most things, it is slightly more complicated than that.

The idea for what would eventually become the internet was outlined first in a series of memos by an academic at MIT (not the military) by the name of J.C.R. Licklider. Licklider conceived of a ‘galactic network’ where a global network of computers would share data; much like the internet today. Licklider wrote the memos in August 1962; he was then quickly snapped up by the DoD in October 1962 to head up the Defense Advanced Research Agency (DARPA). The way in which computers would eventually talk to each other, called ‘packet switching’, was outlined by Leonard Kleinrock, also at MIT, in papers in 1961 and eventually in 1964. It was this conception that allowed the early internet to develop, and its roots lay in civilian, rather than military research.38

The military’s role was to put all of this into action. In 1967, as part of DARPA, the idea of the ‘ARPANET’ was developed. This was the prototype of the internet. Over the course of a number of years, the network was deployed and refined. A major advance during this period was the development of the very backbone language of the internet known as TCP/IP (Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol). This language breaks up data into ‘packets’ that are sent from one computer and reassembled on another.39 In the early 1970s and 1980s, the idea was trialed, and a number of different partners came on board to test the nascent system; most of the people who joined were computer scientists at various academic institutions. Private companies such as Xerox also began participating in the research, which was vital to develop commercially deployable routers.

By the early 1980s, however, the military started taking a backseat. As the technology began maturing, DARPA handed off the ARPANET to other agencies, the first one being Defense Communications. Defense Communications then split the networks into a military only application (MILNET) and a civilian arm of ARPANET. The civilian element of ARPANET was largely driven by the National Science Foundation, which funded the creation of a whole new part of the internet (NSFNET) that connected educational institutions to ARPANET. By 1990, other networks had overtaken ARPANET in terms of connectivity, and it was closed as a communication hub.

The invention of what would become the modern version of the internet did not take place in the US at all, but rather at the European research agency CERN. This had led to the creation of the biggest internet node in the world, CERNNET. A fellow at CERN, Tim Berners-Lee, had long been working on the idea of creating a more useable internet, eventually called the World Wide Web, which would be navigated using a browser. Berners-Lee based this on Hyper-Text Transfer Protocol, or HTTP, which you will no doubt recognize from the addresses on your web browser. Importantly, Berners-Lee never patented the information but shared it freely; it was because of this that the idea was so widely and quickly adopted. If you can believe it, the first website was built and put online on 6 August 1991.40 Barely a decade later, the internet was ubiquitous.

As this history illustrates, the military was able, at least during the Cold War period, to fund cutting-edge scientific research and facilitate its early prototyping. But it did so in constant dialogue with civilian research, and was built on work that had been done before the military’s involvement. And it was precisely when the military stepped away, and the information and protocols became free that the internet exploded into the phenomenon it is today. This has raised the intriguing possibility that the internet would not just have developed without the military (as civilian research was heading in that direction anyway), but that it may have been rolled out and used at an earlier stage too.

MODERN BUYERS: OFFSETS AND COUNTER-TRADE

As we saw in Chapter Two, offsets and counter-trade are often a key reason why buying countries pursue major arms deals. To remind you: offsets and counter-trade are promises on the part of the supplying arms company to invest in the economy of the buyer. This is to ‘offset’ the economic and opportunity costs of buying defense equipment over other spending priorities. They have grown in use and prominence hugely in the defense trade, where they account for 50% of all offset deals globally. By 2016, it is estimated that the defense and aerospace sector will be obliged to provide offsets of $450bn globally.41

Offsets are problematic for a number of reasons. First, offsets cloud and distort procurement decisions. This is because a buying country’s focus will shift from a question of whether or not the product and price are the best to what the purchase will lead to in offset delivery. There is also evidence that the use of offsets actually increases the costs of contracts; a 2012 study in Belgium found that including offsets in defense purchases increased the purchase price by up to 30%.42 Offset contracts are also often included within the national security umbrella that makes the detail of deals confidential, so that citizens and outside parties cannot evaluate whether the investments offered are realistic or not. Companies offering unsuitable products at outrageous prices can simply promise their way to success: what most people would acknowledge comes perilously close to a form of legal bribery.

This is the reason why the World Trade Organization has outlawed using offsets as a selection criteria in procurements: buying countries can request offsets, but cannot base their purchasing decisions on the varying levels of offsets offered between parties. The only sector that is not prevented from doing this is defense, which is given a blanket exclusion.43 It is also why the European Union has long been pushing for a reduction in the use of offsets in procurement contracts. In 2005, for example, a European Union discussion paper found that ‘In principle, offsets are hardly compatible with transparency and fair competition in open markets’.44 The economic impact is obvious: buying companies can be induced to buy the wrong products at over-inflated prices, while suppliers don’t have to improve their products or production techniques to actually win contracts.

The second problem is that when offsets are delivered, it is extremely hard to judge if they have had any real economic impact. In particular, there is the very real chance that the investments that happen would have happened without the involvement of defense firms:45 if there is an economic opportunity in, say, sanitation, it seems odd that it would take an arms firm to make it happen. This was certainly a concern in Finland, where huge offset contracts were attached to the purchase of F/A-18 Hornet jet fighters. Elizabeth Sköns, a defense industry analyst, notes that when an audit of the offset programs was conducted, the outcome was hardly amazing:

The third problem flows from the above concerns. Offset contracts are often hugely complex and bureaucratic. This is made even worse through the use of opaque ‘multipliers’ to give added value to offset investments, as well as the fact that offset projects are awarded complicated offset ‘credits’ rather than simple dollar values. These credits can be awarded for a whole range of activities and can be easily manipulated by savvy offset investors. The result is that, when one finally unravels the impressive statistics and investment figures that are paraded every time an offset investment is concluded, it becomes obvious that the real economic impact was minimal. This was certainly the case with one of the more high-profile and information-rich offset deals: the South African Arms Deal.

Offsets and the South African Arms Deal

When South Africa signed a controversial deal to buy jets, submarines and frigates in 1999, the transaction (known colloquially in South Africa as the ‘Arms Deal’) came with promises of enormous economic development through offsets. In total, the suppliers, mostly British and German, were going to generate R104bn (roughly $15bn at 1999 exchange rates) in economic activity and create 65,000 jobs.47 When defense offsets were presented to the South African public the promise was that they would forever end the guns vs. butter debate: buying arms would be guns and butter.48 It was arguably one of the most vital parts of selling the deal to a country that was still suffering from enormous poverty and deprivation from the apartheid era.

The offsets were split into two kinds: economic activity in the civilian sector (over 80% of the offset commitment) and investment and mutual sales in the defense sector (known by the acronym Defense Industrial Participation, or DIP). Both were a fiasco, which was surprising as defense offsets were identified as a relatively safe bet. But reviewing the defense offsets over a decade later, the board of the body that oversaw South African arms procurements, Armscor, was scathing about what they had achieved:

But it was in the civilian sector that the really crazy stuff happened. To fulfill their obligations, the arms companies had to win ‘offset credits’. These credits, valued in dollars, were supposed to be given on a one-to-one basis, so for every $1 in sales promoted by the company, or every $1 in investment, they were given an offset credit. But they soon became savvy to the fact that the credits were granted with massive ‘multipliers’ if they checked certain boxes like investing in strategic industries, or somehow proved that a tiny investment in a project led to much larger investments by other companies. As a result, the companies were awarded billions in offset credits for rather marginal activities. In one case, Ferrostaal, one of the arms companies, was eventually awarded €3.1bn in offset credits, despite having actually only invested €69m.50

One of the most ludicrous examples of how the system worked was that of McArthur Baths. In 2002, Sweden’s Saab, invested R15m (about $1.5m) in upgrading a set of heated swimming pools in the South African city of Port Elizabeth and undertaking a brief advertising campaign in Sweden to promote the baths.51 In return for this investment, Saab was eventually granted $628m in offset credits.52 The credits were awarded in the most farcical fashion: for every Scandinavian (not just Swedish) visitor to South Africa (not just Port Elizabeth), Saab was granted around $3,830 in offset credits. So any visitor from Scandinavia—on business, going on holiday to Cape Town, seeing family and friends—was treated as if they were going only because of a set of small heated pools in a city not known for attracting tourists at all. These credits were granted even during the 2010 Football World Cup, so that every Swedish attendee of that global jamboree was counted in Saab’s offset points.53

When it came to jobs, the results were unsurprisingly dispiriting. The promise of 65,000 jobs was a huge part of the selling of the Arms Deal, as South Africa suffered from terrible unemployment at the time, and still does. When the final figures were tallied in 2014, it was found that the offset program had only created 13,690 direct jobs.54 And even these figures couldn’t be believed: under questioning, state employees later admitted that they had not bothered to audit these figures, as they didn’t form part of the arms companies’ contractual obligations. In fact, under questioning they admitted that jobs figures were simply taken from the business plans of the investing companies, despite the very obvious fact that these companies would go out of their way to provide the most optimistic figures possible.

The fourth problem is that there is a good chance that the economic investment that does occur during the offset period will simply dissipate once the contracts are over; especially if the supplying country signs a similar deal with another country. This is a particular concern when offset contracts involve the agreement on the part of the selling country or company to preferentially buy products from the producing country. Once the contracts end, what ensures that this will continue? Jurgen Brauer poses this puzzler:

The final problem with offsets, as we will describe in much more detail in our chapter on corruption, is that they pose serious corruption risks. Because they are often conducted under a veil of national security secrecy, they are not subject to oversight. These opaque deals are easy to manipulate to ensure that key decision makers are ‘cut’ into offset contracts after signing. The secrecy attached to the transactions can make them considerably more difficult to identify and trace than traditional bribery schemes.

In summary: offsets are a wash, often increasing prices, delivering limited economic benefit and creating major corruption risks. As Jurgen Brauer and John Paul Dunne noted in a 2009 paper:

THE BAD NEWS: HOW DEFENSE SPENDING CAN HARM THE ECONOMY

So far we have only discussed—and dismissed—the supposed benefits that defense spending brings to the economy. What is often left out of the discussion, however, are the multiple ways in which defense spending can actively harm the economy. We tackle the four primary ones here, but acknowledge that these are by no means the only ways in which defense spending can hurt the economy.

The first is simple: if you spend a huge amount of money on defense, you can be constrained when you need to respond to any sort of economic downturn. One recent example of this has been the US wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. According to Nobel prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz and co-author Linda Bilmes, the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan cost the US economy at least $3trn by 2009.57 They argue that it was these wars that pushed the US economy from a position of a healthy surplus at the end of the Clinton era to one of massive national debt. Indeed, between 2003 and 2008, US debt grew from $6.4trn to $10trn.58 Not only did this limit the US response to the credit crunch, they argue, it may also have played a role in triggering it:

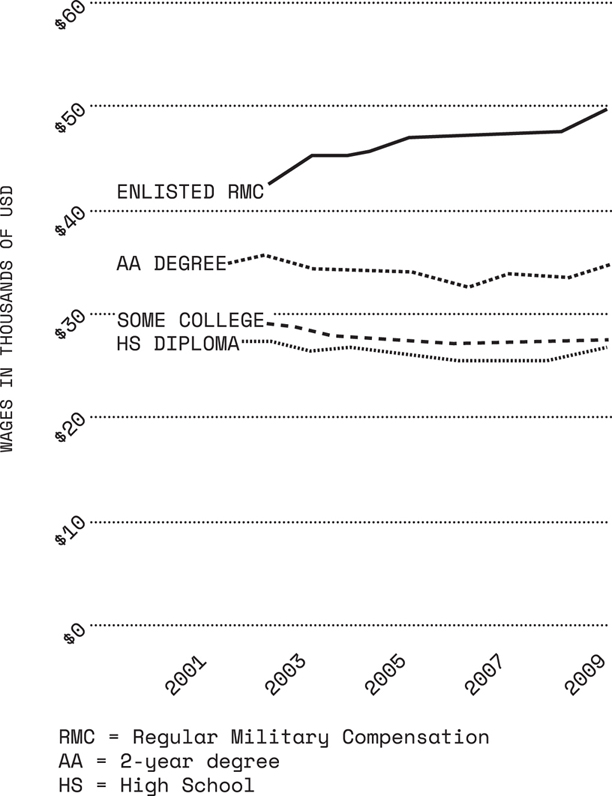

The second way in which defense spending can harm the economy is through what is known as a skills externality. In layman’s terms, this means that the defense industry (including the military) sucks up skilled workers such as engineers and scientists. The defense sector is also likely to pay higher wages and offer more benefits, either directly through state employment or as a result of the favor with which the industry is treated more generally. This can place a major cost on the civilian sector in order to compete with defense industry salaries. In the US, for example, the wages and benefits for military employees are considerably higher than for employees in the civilian sector with similar skill levels; a gap that has been rising consistently since 2001.60 Figure 4.8 shows this clearly.

The third way in which the defense industry, and arms exports in particular, can hurt the economy is through a global escalation in military capacity and instability. This is a no-brainer: if you export weapons to countries that are, at best, questionable allies, you need to buy and develop your own new weapons to maintain military dominance, or increase the quantity of weapons you already have to combat increased regional insecurity. This is wasteful as you render the previous generation of arms irrelevant or draw unnecessary funds into defense procurement. One recent example of this was the decision by France to sell Mistral submarines to the Russian Navy for $1.7bn in 2011. The deal was widely criticized by the US and other eastern European countries as Russia was already posing a military threat to NATO countries. The transaction was only canceled in September 2014 when Russia invaded Ukraine.61 But if that invasion had happened a few years later, Russia would have been in possession of ships that would have significantly boosted its naval forces, compelling other states to buy arms to maintain parity.

The final way defense spending can harm the economy, and one which we will discuss in more detail in Myth 5, is that defense spending is often associated with severe and endemic corruption. Corruption, it is now well recognized, hugely hampers economic growth and development, diverting resources away from human development into unnecessary and wasteful expenditure. That this is the case was illustrated by a fascinating 2009 study by three noted defense economists. Looking at data from a selection of African countries, they found that corruption both increased the military burden and, in the long term, encouraged ongoing economy-deflating rent-seeking behavior. The results showed that

CONCLUSION

As we’ve seen extensively above, the argument that the defense industry is vital to healthy economies is not strongly supported by the data. Not only are the alleged benefits far less substantial than claimed—jobs and innovation are poorly served by modern defense spending—but the downsides of defense spending are unambiguous. The simple fact is that defense spending is good for only one thing: defense. It is a poor job creator, no longer creates that many new technologies and, in the worst case scenario, makes countries poorer. If just a small portion of the currently enormous sums spent on the military were spent on virtually anything else—renewable energy, welfare, tax cuts—the economic benefits would be enormous.