MYTH 6

NATIONAL SECURITY REQUIRES BLANKET SECRECY

In the previous chapter, we discussed how secrecy provides fertile ground for corruption in the defense trade. In almost every case, this secrecy is generated by relying on the ‘national security exception’: that because the defense sector is so crucial to national security it has to remain outside of public knowledge. Certainly, in some very limited cases, secrecy is necessary to maintain national security. But in a good majority of cases, national security is invoked to prevent disclosure of details that are embarrassing to those who govern, or to cover up wrongdoing, or, as seems to be the case in many bureaucracies, because keeping things secret becomes the default position, a force of habit. As one democracy advocate long ago noted, public information is crucial to rule by the people:

And, as we show below, not only does excessive secrecy decrease accountability and hamper good governance, it can actually decrease security as well.

HOW MUCH DOES THE SECRECY BLANKET COVER?

Secrecy is the default position of a good deal of the global defense sector. Secrecy is so widespread that many countries fail to even report how much the military receives in funding. The Government Defense Anti-Corruption Index (GI) is an index developed by the global anti-corruption watchdog Transparency International. The GI assesses the levels of corruption risk in a national defense establishment: what systems are in place to prevent corruption, and how well they are enforced. One part of the ‘corruption risk’ calculation is whether or not countries are transparent in their defense budgeting.

The results of the index were damning: forty of the eighty-two countries surveyed in 2013 did not publish their budget at all.1 Additionally, even published defense budgets often exclude ‘secret’ spending, i.e. how much of the defense budget is spent on top secret items. The risk that this poses in terms of the illicit diversion of funds should be obvious. The GI research also found that 70% of the countries surveyed failed to disclose the amount spent on secret or sensitive items.2

There are some cases in which the details of secret spending may not be appropriate for wide dissemination. But a fundamental part of a democratic system is the agreement to supply this information to publicly respected bodies that can hold the military to account, in particular legislatures. Internationally, most legislatures will allow for top-secret information to be disclosed to representatives in a way that limits its dissemination, but ensures a degree of accountability. Yet 40% of the countries surveyed in the GI failed to give any information at all on funding for secret projects to the legislature.3

Where budgets are published, there is the additional concern that the military establishment may be hiding true expenditures in other budgets, which is known as off-budget expenditure.4 This secret expenditure can be used to undertake politically contentious and unsupported activities, or merely as a means of self-enrichment. Off-budget expenditure became a major problem when Western donors, in particular the World Bank, stipulated in the late 1990s that as part of their aid packages defense spending had to be reduced to an acceptable 2% of GDP. The intent was laudable but the outcomes could be perverse. In Uganda, for example, huge resources were diverted from non-military budgets into a military campaign in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. In 2001, Uganda received the right to exceed the 2% spending, but, in reality, ‘the request was merely an attempt to gain permission to officially spend what was already being allocated to the military’.5

Another example is Nigeria, where problematic off-budget expenditure may be threatening the security of Africa’s biggest country. In Nigeria, ‘security votes’ are off-budget pots of funding that are, in theory, spent on maintaining security. Such ‘security votes’ are reserved for control by the executive, and are not accounted for or subject to audit.6 The sums are believed to be enormous, but their opacity makes it impossible for citizens or civil society to know the amounts. These security votes are allocated on top of the 845 billion Naira (approximately US$5.3bn) budgeted for the security sector in 2014, which already receives a larger portion of the Nigerian national budget than all other sectors.7

There is no doubt that Nigeria faces significant security threats, but the size and proportion of spending on opaque ‘security votes’ have so far had little impact on the safety of citizens in the country. Soldiers complain that they are out-gunned by insurgents.8 Boko Haram is now considered the deadliest terrorist insurgent group in the world: in 2015 alone, 11,000 people were killed in Boko Haram-related violence,9 while an estimated 2 million civilians have been displaced since Boko Haram’s insurgency began.10 A report by the International Crisis Group pointed to ‘corruption, impunity and underdevelopment grievances’, as well as a heavy-handed military approach by government forces, as factors that press citizens to support groups like Boko Haram.11 The executive director of the Nigerian Civil Society Legislative Advocacy Centre (CISLAC), Auwal Musa Rafsanjani, stated that ‘for Nigerians to have less security challenges there should be transparency in the allocation of the huge fund for security in the 2014 budget’.12

Another example is provided by the US, where there are relatively strong oversight and transparency mechanisms in place compared to the majority of countries worldwide. Nonetheless, in addition to excessive corporate influence through legal pathways as discussed in the previous chapter, the US also has problematic off-budget spending. The Overseas Contingency Operations (OCO) account was intended to separate funds for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan from other defense spending.13 OCO spending is a supplemental allocation for ‘war spending’, intended to be faster and more flexible than going through the normal appropriations process, but it has grown significantly since 2001.14 Over $1trn has been spent using OCO funds during the Iraq and Afghan wars, but according to the Friends Committee on National Legislation, much of that money has been used for activities unrelated to the wars, and should have been included in the main Pentagon budget.15 Indeed, when the US undertook new and increased military action in Iraq and Syria in 2014, it could draw on huge reserves of funds that had been granted to the OCO accounts before it had to call for additional money: reflective of how over-funded OCO spending is.

To make matters worse, the OCO is not subject to the same budget restrictions—such as the Budget Control Act—as the primary Pentagon budget. According to the Center for American Progress, ‘the Pentagon has requested $79 billion in OCO funding for FY 2015 and plans to request an additional $30 billion annually through FY 2019. Because OCO funding is not subject to the [Budget Control Act] caps, it has the effect of allowing for a substantially larger defense budget’.16 In 2014, a diverse coalition of organizations wrote a joint letter to Congress to cut the ‘Pentagon’s slush fund’, and close this misleading loophole that allows defense spending to grow, even as the Pentagon’s budget appears to be capped.17

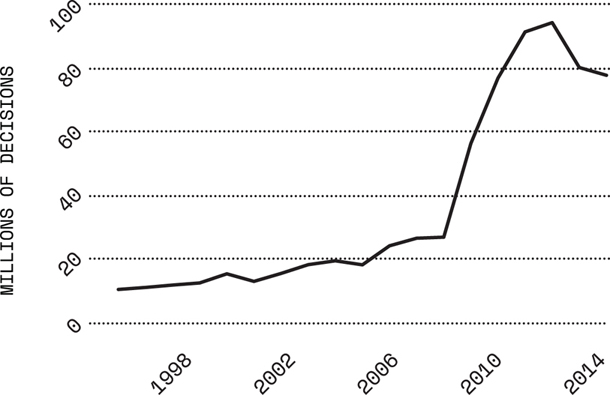

Problems with defense budget transparency are not an isolated phenomenon. Rather, they are best understood as part of a culture of secrecy that defines a lot of defense establishment and industry behavior. This is particularly true of the US, which classifies mountains of documents every year. In the fiscal year 2014, the Information Security Oversight Office reported that there were 46,800 ‘original classification’ decisions in all offices of the US government, i.e. 46,800 decisions which classified information, fortunately a drop from the George W. Bush era.18 However, any document that is produced that uses previously classified material is also automatically classified—what is known as ‘derivative classification’. In 2014, this led to the classification of an astonishing 77,515,636 documents; 17,539,500 of which were given the highest classification of Top Secret.19 As Figure 6.1 shows, using derivative classification has become a worryingly increasing trend.

Keeping so many secrets costs a great deal of money. The US federal government more than doubled its expenditure on keeping secrets in the decade after 2001. In 2014 more than $14.98bn was spent in protecting secrets.20 And the costs have kept going up. In 1995, for example, $2.7bn was spent keeping secrets; this increased to $3.77bn in 1999.21 The rise to $14.98bn in 2013 thus represents an increase of just under 400% since 9/11. To put it in perspective, the cost of classification in the US is equal to the budget of the entire US Environmental Protection Agency.22 Steven Aftergood, who directs the Project on Government Secrecy for the Federation of American Scientists, said that ‘to me it illustrates the most important problem—namely that we are classifying far too much information … The credibility of the classification system is collapsing under the weight of bogus secrets’.23 This was echoed by the US Congress-created Public Interest Declassification Board, which warned that over-classification ‘undermines the integrity of the system’.24

Justifying the cost of keeping secrets is somewhat difficult when it becomes clear just how many people have access to these secrets. In the US and UK, armies of contractors are employed in the intelligence community to process information and undertake intelligence work. Indeed, in the US, nearly 1% of the population has some sort of security clearance. In 2013, it was confirmed that 3.5m people held ‘secret’ clearances, of which 2.7m were government employees and 580,000 contractors. An additional 1.4m people, including over 483,000 contractors, held Top Secret clearances.25 Remarkably, this figure continued to grow: in 2014 it was reported that 5.1m people held ‘secret’ clearances in the US, more than the population of Norway.26

How can a secret known by a million people remain a secret? A ‘secret’ in this system can readily be found by any capable criminal or spy—it just can’t be subjected to public scrutiny and debate.

The culture of excessive secrecy is both illuminated and encouraged by the poor treatment of whistleblowers around the world. Blowing the whistle on corruption exposes fraud, waste and abuse that fritters away taxpayer funds and can put security at risk. In the secretive defense and security sector, it is even more important to have individuals inside institutions watching out for corruption to hold those in power accountable. An understanding that individuals who expose corruption will be protected and their reports taken seriously can have a deterrent effect.

Yet around the world, protections for whistleblowers in this sector are shockingly poor. Just three of the eighty-two countries studied in Transparency International UK’s Government Defence Anti-Corruption Index encourage whistleblowing by defense and security personnel, and implement strong measures to protect those that expose corruption: Germany, Norway and Singapore. Fifty-seven of the eighty-two countries studied (70%) score a 0 or 1 on the question regarding whistleblower protection, indicating that they either have no protections in place at all, or there is no evidence that existing laws are enforced.27

In the US, the cases of Chelsea Manning and Edward Snowden brought the issue of national security whistleblowing dramatically to the fore. But they are part of a broader trend in which the Obama administration has cracked down on government employees who leak information to the press.28 This has been done using the World War I-era Espionage Act, which makes it a crime to allow documents or information ‘relating to the national defense’ into the hands of ‘any person not entitled to receive it’.29 The Department of Justice responded to a Pro Publica report on the crackdown on leaks by stating that it does not target whistleblowers, and that whistleblowers are only legally protected when they raise concerns through internal channels.30 Yet the experience of NSA whistleblowers including Thomas Drake, William Binney and J. Kirk Wiebe, clients of the Government Accountability Project, show that whistleblowers in this sector almost always experience career setbacks, and worse, many of them face reprisals, investigation, lengthy and costly legal battles, and sometimes jail.31

Importantly, progress on general whistleblower protections has not included defense and security personnel. The US Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act of 2012, for example, does not extend to defense and security workers.32 The Obama administration issued Presidential Policy Directive 19 to provide intelligence and security whistleblowers with protection from retaliation but, according to the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University, there are several gaps, including that employees fired for national security reasons are exempt from protection, and the directive does not apply to members of the armed forces or ‘persons in positions of a “confidential, policy-determining, policymaking, or policy-advocating character”’. The Center notes that there is no provision to allow outside reporting if going through internal agency or intelligence committee channels don’t work: ‘the directive … is unlikely to have much effect in cases where the agency itself is complicit in the wrongdoing and the intelligence committees are not willing to interfere’.33

To put the crackdown on whistleblowers in context: since Obama took office in 2009, the administration has brought seven cases under the Espionage Act, more than under any previous president: Thomas Drake, Shamai Leibowitz, Bradley (Chelsea) Manning, Stephen Kim, Jeffrey Sterling (in whose trial the NY Times reporter James Risen was subpoenaed to testify), John Kiriakou and Edward Snowden. Even while aggressively pursuing whistleblowers, the government does acknowledge abuse within the security sector, if its investigations are any indication. In that same time period, the Securities & Exchange Commission took up four enforcement actions of the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) related to defense and security: Smith & Wesson, Armor Holdings, United Industrial Corporation (UIC) and Thomas Wurzel (former president of UIC).34 The DOJ took enforcement actions during this period against Armor Holdings and its employee Richard Bistrong, and BAE Systems. Twenty-two individuals in military and law enforcement products companies were also indicted related to the Armor Holdings incident, but the case was eventually dismissed.35 With corruption and corporate abuse so rampant, surely more should be done to protect whistleblowers?

THE REAL REASONS FOR SECRECY

As the above illustrates, the world, and the defense sector in particular, is suffering from a bad dose of excessive secrecy. This might be understandable if this secrecy stemmed from legitimate and immediate national security concerns. But cultures of secrecy usually develop for other more mundane—and potentially damaging—reasons.

One reason is that excessive secrecy is simply a habit. The Public Interest Declassification Board, for example, argues that the Cold War fostered a culture of global secrecy that merely became a routine. ‘Historically, classification occurred mostly through a rote process, almost always favoring protection and with little restraint or concern for declassification and eventual public access’, the Board’s 2012 Report noted. ‘Over-classification was a natural consequence of having a culture of caution, with every incentive to avoid risk rather than manage it.’36

Other commentators point to more personal and less flattering reasons for excessive secrecy. Daniel Ellsberg, the famous whistleblower behind the Pentagon Papers, has argued that there are strong psycho-social reasons underpinning cultures of secrecy. Ellsberg suggests that the act of keeping secrets in bureaucracies is a way of proving trustworthiness to higher-ups, ensuring that secret-keepers are well thought of by their peers and bosses. At the same time, being given access to secrets becomes a badge of honor, something by which people can measure their status within organizations, particularly those dealing with national security. As Ellsberg has written:

The carrot also combines with the stick: many officials are given the repeated message that if damaging information comes out, it is their fault for not classifying enough. This means that officials may classify simply to play it safe, to save their jobs and careers and avoid institutional censure. In the 1950s, for example, John Moss, widely recognized as the father of the Freedom of Information Act, argued persuasively that ‘the Defense Department’s security classification system is still geared to a policy under which an official faces stern punishment for failure to use a secrecy stamp but faces no such punishment for abusing the privilege of secrecy, even to hide controversy, error, or dishonesty’.38

Elizabeth Goitein and David Shapiro, both of the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law, also suggest that, within bureaucracies, information that has been classified is simply taken more seriously—almost as if being secret is the criterion by which time-pressured officials can sort the wheat from the chaff.39 At the same time, a person sharing the declassified information receives a credibility boost and is listened to. One journalist, quoted by Goitein and Shapiro, recalled a conversation with a former national security official thus:

Organizational politics and turf wars are other reasons why secrecy becomes entrenched. In the mid-1990s, President Clinton appointed a commission to investigate the extent and scale of secrecy in government and give recommendations as to how to remedy it. The commission was headed by Daniel Moynihan, who used his experiences to write a critically acclaimed book in 1999. Reviewing the American experience of secrecy, Moynihan came to believe that secrets primarily became ‘organizational assets’ to be used in turf wars and to achieve ill-defined personal and organizational goals:

The cynical use of secrecy can also become a key way in which governments can raise support for activities that are unjustified based on the actual information. Goitein and Shapiro point to the Iraq war as a prime example. In the lead-up to the war in Iraq, George W. Bush referred to the National Intelligence Estimate as evidence that Iraq was attempting to produce weapons of mass destruction, despite the fact that the estimate included qualifications and cautions from various agencies about the data. Only a small number of congressmen were given access to the full version. However, when the matter came before Congress to be debated, the full assembly was given an unclassified version that left out the dissenting opinions. A later congressional committee found that the unclassified version provided readers ‘with an incomplete picture of the nature and extent of the debate within the Intelligence Community regarding these issues’.42

Goitein and Shapiro also point to another reason for excessive secrecy, which we have referred to repeatedly: the desire to cover up wasteful, criminal or simply embarrassing information.43 One example of this can be found in the controversial Timber Wind Project. Timber Wind was part of the much-maligned Star Wars program to build a means of intercepting incoming nuclear weapons in the US, and was specifically mandated to investigate using nuclear-propelled rockets as interceptors. In the early 1990s, details of the project were leaked to Steven Aftergood of the Federation of American Scientists. Aftergood discovered that the project had been wrongly classified as a ‘special access program’, limiting knowledge of it. Aftergood thus wrote to the inspector general, who investigated the matter. The inspector general confirmed that the over-classification had not only ‘limited discussion and debate on the feasibility of the technology and alternative applications of the technology’,44 but that the classification was kept in place after Aftergood had been given the documents ‘to avoid embarrassment that may have resulted from the unauthorized disclosure’.45

HOW SECRECY REDUCES NATIONAL SECURITY

In addition to being concerned about unnecessary secrecy, we should also be deeply worried about how national security can be actively undermined by secrecy. This comes about three key ways.

First, excessive secrecy creates the space for corruption, waste and mismanagement. And, as we have seen, corruption and waste actively reduce national security by diverting resources away from actual national security needs, reducing the legitimacy and efficacy of the military, and encouraging government behavior that sees the defense budget as a means of self-enrichment rather than a scarce resource that needs to be used to maximize security.

Second, excessive secrecy curtails proper debate about foreign and defense policy, and can lead countries into dark places. This was clear in the case described above, where selected declassification of materials limited the debate about whether or not to invade Iraq, tilting in favor of the Bush administration’s preference for war. This may not have caused the war in Iraq—the conflict was driven by multiple factors—but it certainly led many to support the war based on faulty information and muddied the water considerably.

Third, and finally, excessive secrecy can markedly reduce the ability of those in charge of national security to do their jobs efficiently. This is particularly true when various defense and intelligence agencies fail to share information between them. One very clear example of this was the build-up to 9/11. Reviewing the facts surrounding the matter, the 9/11 Commission, set up to investigate the reasons why the attacks weren’t stopped, noted that the policies and practices of the agencies involved stopped information held between them being integrated into a single useful picture:

This insight was clearly lost in the post-9/11 acceleration of classifications.

WHAT CAN BE DONE

The fact that national security has driven excessive secrecy should be of concern to everyone around the world. And there is something meaningful and concrete that can be done. In 2013, the Open Society Justice Initiative undertook a massive survey of the impact of national security on democracy, and developed a framework of principles that could guide all future national security legislation to ensure the greatest possible degree of openness and democracy. Drawing on consultations with over 500 experts in seventy countries, the program produced what are known as the Global Principles on National Security and the Right to Information (also known as the Tshwane Principles).47 If governments around the world would agree to adopt the Principles, and make them a reality in their legislation and conduct, it would mark a fundamental change in how secrecy and national security are conceived. The following points summarize the Tshwane Principles on National Security and the Right to Information:48

•The public has a right of access to government information, including information from private entities that perform public functions or receive public funds.

•It is up to the government to prove the necessity of restrictions on the right to information.

•Governments may legitimately withhold information in narrowly defined areas, such as defense plans, weapons development and the operations and sources used by intelligence services. Also, they may withhold confidential information supplied by foreign governments that is linked to national security matters.

•But governments should never withhold information concerning violations of international human rights and humanitarian law, including information about the circumstances and perpetrators of torture and crimes against humanity, and the location of secret prisons. This includes information about past abuses under previous regimes, and any information they hold regarding violations committed by their own agents or by others.

•The public has a right to know about systems of surveillance, and the procedures for authorizing them.

•No government entity may be exempt from disclosure requirements—including security sector and intelligence authorities. The public also has a right to know about the existence of all security sector entities, the laws and regulations that govern them and their budgets.

•Whistleblowers in the public sector should not face retaliation if the public interest in the information disclosed outweighs the public interest in secrecy. But they should have first made a reasonable effort to address the issue through official complaint mechanisms, provided that an effective mechanism exists.

•Criminal action against those who leak information should be considered only if the information poses a ‘real and identifiable risk of causing significant harm’ that overrides the public interest in disclosure.

•Journalists and others who do not work for the government should not be prosecuted for receiving, possessing or disclosing classified information to the public, or for conspiracy or other crimes based on their seeking or accessing classified information.

•Journalists and others who do not work for the government should not be forced to reveal a confidential source or other unpublished information in a leak investigation.

•Public access to judicial processes is essential: ‘invocation of national security may not be relied upon to undermine the fundamental right of the public to access judicial processes’. Media and the public should be permitted to challenge any limitation on public access to judicial processes.

•Governments should not be permitted to keep state secrets or other information confidential that prevents victims of human rights violations from seeking or obtaining a remedy for their violation.

•There should be independent oversight bodies for the security sector, and the bodies should be able to access all information needed for effective oversight.

•Information should be classified only as long as necessary, and never indefinitely. Laws should govern the maximum permissible period of classification.

•There should be clear procedures for requesting declassification, with priority procedures for the declassification of information of public interest.

It is up to us, as global citizens, to compel our governments to act on these principles, for the sake of more openness and transparency, enhanced justice and democracy, and greater security for all.