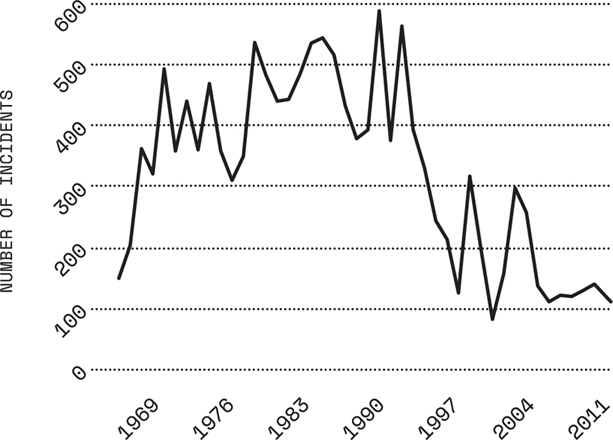

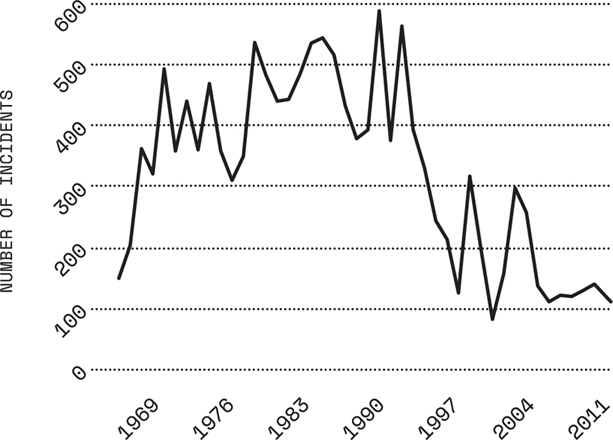

Figure 7.1 Number of transnational terrorist incidents, 1968–2011

NOW IS NOT THE TIME

If all of the arguments that those who support the arms trade status quo presented so far have not convinced you to leave it well alone, there is one more argument up their sleeve: the world today is too dangerous to imperil the status quo and challenge the arms business. In fact, so the argument goes, the world is more dangerous now than it ever has been in the past. We need to stick with this course, it is argued, until we’ve turned the tide, rolled back the wars and achieved a peace in which we can breathe and take stock. We need first to win the ‘war on terror’, and to deter the threats posed by a rising Russia and China, before we can begin to dismantle our defenses.

Our argument is different. We don’t put forward a particular explanation for the world’s armed conflicts and security problems. What we do is to debunk the myth that we are living in a period in which the world’s threats justify an international arms business of the scale, type and influence that we have today. In fact, we suggest that the arms trade has not only corrupted government procurement and international trade, but it is insidiously perverting the course of judicious political analysis. Now is precisely the time to debate, openly and transparently, the nature of the global arms business and its indefensible logic.

IS THE WORLD REALLY MORE DANGEROUS?

The drumbeat of imminent and permanent crisis is powerful and persistent. And it is escalating. Leaders around the world, large parts of the media and the swathes of the commentariat repeat the claim ad nauseam, that our current threats make this the most dangerous time in human history. In 2013, for example, British Foreign Secretary William Hague declared: ‘The world is becoming more dangerous. The risk has risen.’1 Similarly, in 2012 the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Martin Dempsey, told the United States Congress that ‘in my personal military judgment, formed over thirty-eight years, we are living in the most dangerous time in my lifetime, right now’. Dempsey further detailed the sources of his fear: ‘There are a wide variety of non-state actors, super-empowered individuals, terrorist groups, who have acquired capabilities that heretofore were the monopoly of nation states … I wake up every morning waiting for that cyber attack or waiting for that terrorist attack or waiting for that nuclear proliferation.’2

There is no doubt that the world may be faced with problems, but the claim that we live in the most dangerous period in human history is simply unsupported by the data. There are genuine threats, but they are routinely exaggerated and distorted. The threat of terrorism—which often ranks highest in the listing of fears—is hugely overstated and objectively quantifiable as such: an example of the process of ‘threat inflation’, which we discuss in detail below. Meanwhile, other tangible long-term threats, such as climate change, are ignored or brushed aside. Threats are framed in such a way that the solution is pre-defined: more weaponry, heightened vigilance, more authority vested in the defense and security chiefs. These arguments are demonstrably false and dangerous.

Less heard than the ‘dangerous times’ trope is the counter-argument, that we are in fact living in the most peaceful era in human history. Steven Pinker, with his widely acclaimed 2011 book The Better Angels of Our Nature, is the leading proponent of this view. Drawing on volumes of evidence, Pinker argues that all the statistics point to a massive long-term reduction in violent conflict and a reduction in intentional violence across all areas of human life.3 To explain this remarkable and laudable trend, Pinker details the growth of states and the rule of law, the expansion of education, the human rights revolution and the feminization of politics.

Remarkable as Pinker’s claim may seem, he is in line with the general view among scholars and statistical authorities that look at long-term trends. Among the trends that have been well-documented are:

•The decline in number and scale of mass atrocity events.4

•Decline in the number of armed conflicts and people killed in each.5

•Decline in famines.6

Let’s narrow the conversation to armed conflict for the moment, where the research consensus on the long-term trends is very strong.

The most significant global threat of violence in terms of capacity for destruction is war between the major powers. This peril was horribly realized in the devastation of World War I that began just over a hundred years ago, and its sequel from 1939 to 1945. The degree of political, social and economic upheaval that these conflicts caused cannot be overestimated. World War I ended with 16 million people dead, and another 20 million wounded. World War II surpassed even this deadly toll, leaving in its wake 60 million people dead, representing 2.5% of the global population.

Since the end of World War II, there is one key statistic we need to keep in mind: zero. That is precisely the number of wars between major powers since 1953, the number of nuclear conflicts and the number of wars involving direct conflict between two states in Europe.7 While many will and in fact have argued that this number was made possible by large military build-ups, particularly in the West, another set of important statistics helps us understand that the real peace dividends were found following the end of the Cold War, when military stockpiles and proxy wars were reduced.

Of course the world still experiences an unacceptable number of conflicts. But these are much fewer than during the middle of the 20th century; and, importantly, they tend to be less violent. In 1991, for example, two years after the Berlin Wall had fallen, there were fifty-two conflicts around the world. This fell to the low thirties, on average, between the mid-1990s and early 2010s.8 The total, it should be noted, increased to forty in 2014, which is worrying, but still less than in the early 1990s. Conflicts claiming 1,000 or more lives declined 50% from fifteen in the early 1990s to just seven in 2013.

In addition, the conflicts that take place are generally less violent. The Human Security Report asserts that the average international conflict in the 1950s killed over 21,000 people a year on the battlefield; in the 1990s that average had declined to approximately 5,000, and in the first decade of the new millennium it was less than 3,000.9 And we are getting better at counting wars and violence in wars. The Sudanese‒Ethiopian reciprocal cross-border attacks of the mid-1990s, for instance, don’t show up in any databases, because both sides kept them secret.10 Today it’s inconceivable that an air raid on a civilian target that killed between 1,000 and 1,800 people would remain entirely unreported for ten months (social media and the internet has vastly increased the ability of even the most remote places in the world to be reported on), but that is precisely what happened following the Ethiopian air raid on the market town of Hausien on 22 June 1988.11 Overall, the downward trend in armed conflict has continued into the 2000s.12

Scholars take their time to analyze data and write their books and reports. Journalists, commentators and politicians respond to the day’s events. The long-term decline is not in dispute. Indeed, the indicators for battle deaths and conflict-related humanitarian crisis hit their all-time low in the years 2005‒2008.

You may ask: what about Syria, one of the most deadly conflicts of the last two decades? And you’d be right to ask; Syria has almost singlehandedly reversed the downward trend of the past twenty years. But it is important to bear in mind two things: first, the Syria crisis, as we discuss later, is precisely a function of the broken politics in which the arms trade thrives and which the arms trade creates. Second, even with the Syria crisis, the world is considerably less violent than it was during the majority of the Cold War.

Thus, while 2014 was the most deadly year for conflict for two decades. Erik Melandor, director of the Uppsala Conflict Data Program, points out that ‘2014 nevertheless represents a low level of violence compared to the repeated spikes of war fatalities during the Cold War’.13 In 2014, the number of battle deaths was estimated to be around 100,000; by comparison, they reached over 600,000 in the early 1950s (during the Korean War), about 380,000 in the early 1970s (during the Vietnam War), and hovered around 280,000 between 1983 and 1988 (during the deadly Iran‒Iraq War and the civil wars in Angola and Ethiopia).14 The 2015 Global Hunger Index, compiled by the International Food Policy Research Institute, Concern Worldwide and Welthungerhilfe, on the topic of how armed conflict creates hunger, noted that major famines had been all but abolished during the last decades of the 20th century. While 117 million people perished in great and calamitous famines in the hundred years from 1870 to 1970, the figure for the last twenty-five years is just 1.4 million. However, the same report observed with worry that conflict-related starvation had been increasing over the last seven years, notably in Somalia, South Sudan, Syria and Yemen.15

What this clearly suggests is that there are newly emerging challenges, and the last few years have posed worrying questions about the trends towards greater peace and security. But they should not be read as proof that the world is more dangerous now than it has been in the past: even if the media coverage does not reflect it, the last two years of conflicts still come nowhere near the violence of the Cold War.

WHY DOES THE WORLD FEEL SO DANGEROUS: EXPLORING THE DOMINANT NARRATIVE OF THREAT

As we have seen above, a few years after the Millennium, the world was at its most peaceable in recorded history. Nonetheless, a 2006 Gallup poll revealed that 76% of Americans believed that the world was, in that year, more dangerous than it had been anytime in the recent past.16

What might explain this? Some reasons lie in the psychology of threat perception. Threats that are new and unknown will figure more highly than those that are familiar—even if the latter are objectively greater. Threats that are incalculable or somehow alien will be seen as their worst possible manifestations. We are irrationally scared of sharks. Events that are on the TV news will be more salient than those we read about in the papers or in specialist articles, or which never reach the media at all.

Other reasons lie in the deliberate or casual misrepresentation by politicians. Playing to people’s fears—including exaggerating those fears—is the oldest trick in the politician’s playbook. This is where the arms business enters, as an accessory to this trick.

And there can be no doubt that the terrorist crime of 11 September 2001 generated deep fears among Western (and especially American) publics. Not only were civilian airliners turned into weapons of conspicuous destruction, but the subsequent anthrax scare drew attention to the dangers of chemical and biological warfare agents in the hands of non-state actors bent solely on devastation. The fear that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein possessed nuclear weapons ready to launch on a hair trigger, evoked still deeper fears. The ideologies of Al Qaida militants, and more recently the Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham [ISIS is Islamic State of Iraq and al Sham] (ISIS), are so alien and demonic that people are deeply afraid that the worst may transpire.

Fortunately, those fears are massively disproportionate to the actual threats. In 2013, for example, 11% of US citizens were very worried, and 29% somewhat worried, that someone in their family would be a victim of terrorism.17 But, that same year, the US government confirmed that only sixteen American citizens (not including soldiers) had been killed as a result of terrorism worldwide.18 In fact, you are more likely as a US citizen to drown in your bathtub (a 1 in 800,000 chance) than die from terrorism (a 1 in 3.8 million chance).19 And even this may be an overestimate: in 2013 the Washington Post reported that, based on the previous five years, there was only a 1 in 20 million chance of dying in a terrorist attack: two times less likely than dying from a lightning strike.20 Toddlers, using weapons found in their own homes, have killed more Americans than terrorists in recent years.21

Of course, one would hope that the US government’s spending on the ‘war on terror’ would make America safe (or at least safer) from terrorist attacks. The low numbers of Americans killed by foreign terrorists could equally be taken as a sign that the US Department of Homeland Security, the CIA, the National Security Agency and the DoD are doing their job well.

However, it is crucial to consider that the ‘war on terror’ might have been a horrendous error. Such an argument runs like this: the attempt to impose a military solution on complicated political problems was simplified thinking with a false promise of total national safety. In turn, the militarization of the response—as seen in the massive expansion of military deployments, arms spending, and the license to do anything in pursuit of national security—has in reality worsened the problem of armed violence in the world.

This argument begins with an important fact: transnational terrorism is on the decline. As Todd Sandler argues in a 2014 article assessing how we study and track acts of terrorism, by the major indices which detail terrorism the decline is substantial.22

Figure 7.1 Number of transnational terrorist incidents, 1968–2011

It is notable that the decline had set in well before 2001. If we take the number of fatalities caused by terrorists, 2001 marks a clear spike, because of 11 September. But a single spike, however terrible, is not indicative of a statistical trend. Looking back, it seems that the counter-terror policies of the 1980s and 1990s, aimed at pressuring governments to end state sponsorship of terrorist organizations, was actually working, and 9/11 was an exceptional and tragic outlier.

One thing that happened in the aftermath of the trauma of 9/11 was ‘threat inflation’: political leaders and pundits inflated the perils that America was facing. ‘Threat inflation’ refers to the gap between perceived and actual threats. It is defined by the scholars Trevor Thrall and Jane Cramer as ‘the attempt by elites to create a concern for a threat that goes beyond the scope and urgency that a disinterested analysis would justify’.23 Or, in simpler terms, threat inflation is when enormous amounts of fear are generated far beyond what the facts would warrant.

Threat inflation is remarkably easy to do. The difference between popular fears and realities is well known to domestic politicians and policemen. A 2011 Gallup poll found that 68% of Americans think crime is on the rise.24 In fact, between 1993 and 2012, the violent crime rate (homicide, robbery, rape and aggravated assault) in the United States dropped by just under 50%.25

The security sector has a strong record of engaging in threat inflation. During the early stages of the Cold War, for example, American policy makers and military leaders loudly worried about first a ‘bomber gap’ and then a ‘missile gap’, claiming that the USSR was massively outpacing US production of bombers and nuclear missiles. In 1959, US intelligence estimates suggested that the USSR would be in possession of between 1,000 and 1,500 nuclear-capable intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) compared to America’s paltry 100. In reality, by September 1961, the USSR had only four ICBMs at its disposal, ‘less than one half of one percent of the missiles expected by US intelligence’, as Stephen Van Evera points out.26 More recently, Saddam Hussein turned out not to possess weapons of mass destruction after all. The practice extends, as retired Air Force Lieutenant-Colonel William Astore notes, to North Korean ballistic missiles, Iranian nuclear weapons production and increased Chinese military production. While all are real concerns, they ‘pale in comparison to the global reach and global power of the United States military ... All this breathless threat inflation keeps the money rolling (along with the caissons) into the military’.27

There are a host of reasons why threat inflation might happen. Scholars sympathetic to the difficulties of governance will argue that decision makers are always on the back foot, trying to make sense of a confusing world with limited intelligence. Politicians may see the inflation of a threat as a win‒win situation: if the threat does not materialize, they can point to their preventative measures, and if it does, they can argue that they had seen it coming all along and that even more needs to be done to prevent it. Academics who study the psychology of fear point to how difficult it is to analyze security risks in cultural environments that have been shaken by recent unforeseen attacks.28 And then there are the various psychological short-cuts that are made that can turn the most unrealistic concerns into national emergencies. Not every possible threat is a probable threat. Confusing the two allows worst-case thinking to claim the day. The problem with that is, as security expert Bruce Schneier writes:

It substitutes imagination for thinking, speculation for risk analysis, and fear for reason. It fosters powerlessness and vulnerability and magnifies social paralysis ... By speculating about what can possibly go wrong, and then acting as if that is likely to happen, worst-case thinking focuses only on the extreme but improbable risks and does a poor job at assessing outcomes.29

One example of this is the tendency to conflate a sense of security with one’s actual security, which can often be hugely different. It is entirely possible to feel secure when you’re actually very insecure (sitting in your cozy home on a normal night when there is in fact an intruder outside), and feel very insecure when you’re really safe. If you are bombarded with images of violence and war, especially if those images are framed in terms of threat, they are likely to make you feel deeply insecure, even if the reality is somewhat different.

Nowhere is this tendency more pronounced than in relation to defense issues and the global arms industry. Many scholars point to how particular players—the defense industry, the military, like-minded leaders and a pliant commercial press—can collude to create magnified perceptions of threat to justify unpopular military endeavors, pursue particular foreign policy ideologies and divert massive financial resources to the industries and individuals who will be paid to diffuse the threat.30 Certainly, defense companies are past masters at presenting, through their advertisements directed at government buyers, the world as a deeply dangerous place, and their products as the solution. These players are particularly well placed to set the agenda of fear as they have both the pulpit to do so, often brief decision makers directly on the security environment, and have a monopoly on intelligence that can be hard to counter in the heat of the moment.

A pertinent example is the US invasion of Iraq in 2003, which was foregrounded by the national trauma of 9/11 and pursued on the basis of the constructed and largely imaginary threats posed by Iraq’s Saddam Hussein. It is now well-known that officials in the Bush administration, many of whom were part of the controversial Project for the New American Century, had been pushing for an attack on Iraq since at least 1998, believing that it would lead to a radical reshaping of the Middle East along lines favorable to the US.31 Shortly after 9/11 took place, Bush and his officials were assiduous in popularizing four related ‘threats’ that drew on the emotion of 9/11 and focused a target on Saddam Hussein. These four threats are identified by Chaim Kaufman as follows:

He was an almost uniquely undeterrable aggressor who would seek any opportunity to kill Americans virtually regardless of the risk to himself or his country;

He was cooperating with al Qaida and had even assisted in the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks against the United States;

He was close to acquiring nuclear weapons; and

He possessed chemical and biological weapons that could be used to devastating effect against American civilians at home or US troops in the Middle East.32

These were powerful claims: multiple polls found that Americans, in the lead-up to the war in Iraq, believed them to be substantially true.33 However, since the Iraq war has taken place, every threat has been successfully debunked. Weapons inspectors at the time did not find any trace of nuclear activity or a chemical weapons program, and none were found by US troops on the ground.34 Hussein had not worked together with Al Qaida at all,35 and actually saw them as a potential threat since Al Qaida had identified his regime (amongst multiple others) as an enemy. Hussein, while undoubtedly a vicious dictator, was not irrational, as evidenced by how successfully the US had deterred his international ambitions following the first Gulf War.

And we now know that the Bush administration was well aware of these facts, actively manipulating intelligence gathering and tinkering with its analysis to give these fears credence.36 After CIA officials rubbished the intelligence reports of Iraqi defectors, for example, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld created a new body called the Office of Special Plans (OSP).37 The OSP collected its own raw, unfiltered intelligence and ensured that it reached the highest levels of decision making, bypassing the usual checks, balances and analysis that intelligence agencies provided.

Making it worse, those who were worried about going to war in Iraq based on flimsy facts simply could not contend with how effectively the US administration defined the problem, controlled the information and dominated press cycles. One analysis of press coverage over two weeks between January and February 2003 discovered that of the 393 sources quoted, half were government officials. And when a source criticized the drumbeat for war, they were far more likely to be from foreign (including Iraqi) government officials.38

Together, these activities convinced the American population, and good parts of the rest of the world, that Iraq posed a clear and immediate threat: the threat was inflated and people bought it.

Then there is threat simplification: the argument that the world—or a country—can be made safer by physically eliminating enemies one by one. This was the initial logic of the ‘war on terror’: that only a special kind of person could be a terrorist, that they were few in number, and so if they could be killed more quickly than terrorist organizations could train them, the war would be won.39 This approach was also adopted in Iraq, when American soldiers were issued a deck of playing cards with the names and faces of the fifty-two most wanted members of the deposed regime. The implicit logic was that once the cards had been scooped, the job was done. It didn’t work out that way: as US soldiers told DoD analysts when fighting the insurgency a few years later, that the strategy of killing ‘high-value individuals’ simply didn’t work:

When we asked about going after the high-value individuals and what effect it was having, they’d say, ‘Oh yeah, we killed that guy last month, and we’re getting more IEDs [improvised explosive devices] than ever.’ They all said the same thing, point blank: ‘[O]nce you knock them off, a day later you have a new guy who’s smarter, younger, more aggressive and out for revenge.’40

America was painfully relearning an old lesson: terrorism is a tactic, not an organizing principle of insurgency. Wars can be won when the military is utilized in service of a political objective, and not when politicians are required to support the military, no questions asked. Under President Obama, the US administration has quietly abandoned the language of ‘war on terror’ in favor of ‘countering violent extremism’. But the military juggernaut rolls on.

There is a long history of statesmen starting wars expecting that they will achieve a quick, clean victory that will boost their standing at home and their authority abroad. It rarely works out that way. The left-leaning historian Gabriel Kolko, in Century of War, attributes European wars to the self-delusions of political leaders who believed that they could control, and in a meaningful sense ‘win’ a war: ‘Any account of war in our times must confront the fact that the rulers of nations have persistently exhibited a myopia that has compounded the impact of war on the populations of innumerable countries throughout the century.’41 Had the aristocrats who plunged so recklessly into that conflagration appreciated that the war would bring down Europe’s three most powerful monarchies and forever cripple the global imperial status of the French and British ‘victors’, as well as killing the flower of the generation of their own children, they would surely have thought twice. But they possessed no such foresight. The conservative historian Niall Ferguson, concluding his epic The Pity of War, agrees in essence: ‘The First World War … was nothing less than the greatest error of modern history.’42

The blowback from the US funding of the Afghan mujahidin in the 1980s has been noted. The blowback—or perhaps ‘blow-around’—from the 2003 invasion of Iraq is turning out to be far more serious. Where do we see the most significant uptick in armed violence over the last decade? The places are all those affected by the Iraqi civil war and attendant militant extremism (Iraq itself, Syria), or by attempts to win the ‘war on terror’ primarily by military means (Afghanistan, Somalia, Yemen), or the fallout of Western military intervention (Libya and the Sahara). The South Sudanese civil war is an outlier—but the South Sudanese leadership was initially embraced by the US as a bulwark against terrorists in Khartoum and, as described in this book, Western governments turned a blind eye to their vast and corrupt arms purchases. And Russian President Vladimir Putin explains and justifies his bellicose posture, including his actions in Ukraine and involvement in Syria, as no more than exercising the right of national security to override international norms, as the US invoked in Iraq.

Take the conflict that has almost single-handedly pushed up current conflict deaths to early 1990s levels, the devastating civil war in Syria. While the conflict in that country is driven by multiple factors—a dictatorial regime, regional spillovers of extremism, an international community that has shifted between vacillation and interference—there is no doubt that the level of violence in that country is a direct result of decades of arms transfers to the region. As we’ve discussed previously, the spectacular success of ISIS in Syria and more widely has in large part been facilitated by the fact that they have been able to seize enormous quantities of arms, particularly in Iraq. There are, in fact, so many arms in the region, and more arriving every day, that if parties want to carry on fighting, they could do so for generations.

In short, almost everywhere we see a recently escalating conflict, the fingerprints of the global arms business and its political fellow travelers can be found, both in provoking conflict and in profiting from it. To repeat: we do not argue that these wars are deliberately engineered by arms manufacturers and traders. But the entanglement of the arms business in the political decisions generating today’s wars demands our scrutiny. We cannot take the claims of the defense and security lobbies at face value.

CONCLUSION: IS DEFENSE SPENDING THE ANSWER TO THE THREATS WE FACE?

Even if you don’t buy all the arguments above—if you think the world is more dangerous than ever, or at least extremely dangerous—you may still want to ask the question: is the arms trade as it is now, and defense spending generally, part of the solution or part of the problem?

We have discussed the impact of the arms trade in its various facets throughout the book so far. And it is clear, from the available historical evidence and current data, that the arms trade in its current incarnation can actually make countries less secure, current conflicts more violent, and draw resources away from diplomatic efforts that can negotiate an end to wars (or prevent them happening in the first place). The arms business is also part of a wider security narrative that inflates threats and defines them as problems to be solved by military measures rather than political processes. Those who make and sell weapons aren’t honest brokers: they need to be challenged and their real motivations revealed.

Because if the arms trade is a big part of what makes the world insecure, there simply is no wrong time to challenge the arms trade. Instead, challenging the arms trade in its current form is desperately necessary. Right now.