In 1875, after years of tinkering with his Statue of Liberty design, Bartholdi shaped his definitive model. It was made of clay and stood four feet tall. A colossal version of this model would eventually go up in New York Harbor eleven years later. As a work of art, the sculpture was banal. There were statues of liberty galore in nineteenth-century France, and Bartholdi mimicked their neoclassical form. Even his symbolism was standard. Broken chains had long represented freedom from bondage; torches commonly stood for enlightenment, as did rays of light; the tablet evoked the majesty and authority of the law. Bartholdi himself admitted that his statue “wasn’t a great work of art.”1 But he knew that its formal artistic originality was beside the point.

Above all, the Statue of Liberty is a masterpiece of engineering and technology. Its Greco-Roman drapery masks what was, for the late nineteenth century, a great technical accomplishment. When we look at the Statue of Liberty, we imagine a huge version of an ordinary statue, a solid stone or iron structure firmly anchored into the hard earth of Bedloe’s Island. In fact, the statue is far too large to have been made that way, and even if it could have been, Bartholdi would have been unable to proceed as he did, namely to design and build the monument in a Parisian atelier and then to dismantle it for shipment to New York. So what we see is an optical illusion of sorts. In reality, the visible statue is but a wafer of oxidized copper hammered to a breadth of just 3/32 of an inch—slightly thicker than a penny. It could never stand on its own. Instead, it hangs—all 151 feet of it—on an elegant, invisible skeleton of iron conceived by Gustave Eiffel. In a sense, the Statue of Liberty is a modernist Eiffel Tower sheathed in the respectable garb of classical antiquity. It is analogous to the great nineteenth-century train stations whose core structures were shaped from iron and glass but then discreetly hidden behind conventional facades of stone. Urban planners believed the new stations would be too shocking if they weren’t made to blend in. The Eiffel Tower, built for the 1889 International Exposition, explicitly broke with this model by uncloaking the Statue of Liberty’s wrought-iron skeleton for all the world to see. Eiffel’s modern pyramid would stand as a pure display of engineering genius that served no purpose other than to reveal a new form of art—though even he added some unnecessary architectural adornments.2 It’s worth noting that although Liberty’s skeleton is invisible from the outside, visitors can see it when they venture inside. A narrow spiral staircase winds around the skeleton’s central pylon all the way to the interior of the head. From that vantage point visitors can look out on the harbor through a windowed dome; en route they can admire the extraordinary metal armature that holds the statue up.3

In the 1860s and ’70s Eiffel had made himself perhaps the world’s greatest builder of railway bridges. Most notable are those that span the Douro River in Oporto, Portugal, and the Truyère in Garabit, France. In both, Eiffel pioneered the use of extraordinarily long iron girders, sweeping arches with no center beams, and flexible joints designed to absorb heat and cold and the shock of moving trains. The sweeping arch allowed Eiffel to anchor his bridges in riverbanks rather than in the water, making them at once easier to build and more stable. To manage the brisk winds howling through a deep river valley, Eiffel substituted spindly trusses for the solid iron beams that bridge builders had traditionally used. Trusses are beams pierced with triangular holes through which the wind can blow—unlike solid beams that meet the wind head on and require complex counter-forces to keep them in place. Liberty’s skeleton is also made of trussed iron pylons, though here the virtue of the truss-work is its relatively light weight and flexibility rather than openness to wind, which buffets the statue’s copper skin and only indirectly the trusses themselves.

To create Liberty’s skeleton, Eiffel adapted one of his bridge pylons for use as the statue’s central pillar. But since he was building one structure to support another, he had to innovate. Perhaps his biggest challenge was to brace the huge copper form against the high winds that sweep through New York Harbor, and to do so while holding together the hundreds of thin copper plates that form Liberty’s skin. That exterior, of course, had to be propped up as well, since it couldn’t stand on its own. Eiffel attacked these problems by extending a web of lightweight trussed beams out from the central pillar. Those secondary beams stretched toward the copper skin but didn’t touch it directly. To hang the exterior on its skeleton, the engineer used a single bolt to attach flat iron bars to the far end of each beam and then to hundreds of points on a fine lacework of copper itself attached to the skin. Since the thin iron bars were flexible and the single-bolt attachments allowed some give, the bars acted like simple springs. These springs absorbed the statue’s movement in the wind, ensuring the stability of the central pylon and the truss-work that branched out from it. This ingenious structural system meant that the copper exterior was not attached directly to the skeleton but rather bobbed around it on a great many rudimentary springs. Although each individual spring was relatively weak, by working in concert the ensemble of springs created a superior kind of strength—tough but elastic, rigid and supple all at once.

What was especially innovative about Eiffel’s system was that he didn’t need to rest the upper parts of the structure on the lower ones, as in most traditional buildings. Instead, he hung the monument’s exterior on a strong but relatively lightweight interior system of support. This approach allowed the statue to rise to considerable height while being sturdy and unthreatened by wind. In conceiving it, Eiffel anticipated the architectural principles later used in the skyscrapers of Chicago and New York. He produced, as Marvin Trachtenberg has noted, one of the first “great curtain wall constructions.”4

The structure nonetheless had to be anchored on the bottom. This Eiffel achieved by having his skeleton stand on four metal plates, each of which would eventually be rooted deep into a stone pedestal erected on Bedloe’s Island. Eiffel’s final structural problem involved Liberty’s up-stretched arm and torch, an appendage that rises almost forty-one feet above the statue’s crown. To build it, the engineer lined the arm and torch with an asymmetrical trussed girder delicately attached to the copper skin. Here, Eiffel employed the lessons learned from his bridges to create an appendage that would remain firmly connected to Liberty’s upper body without requiring a bulging undercarriage of support that would have ruined the proportions of the sculpture. But during construction Bartholdi or his workmen changed Eiffel’s design and in the process weakened the arm, which may, in any case, have required more support. During the statue’s first century, engineers had to reinforce it twice (1932 and 1984) to keep it safe. Still, Eiffel’s solution was brilliant for its time and allowed visitors to climb to the torch’s viewing platform high above Liberty’s head. Those making the ascent could feel the entire arm swaying eerily but harmlessly in the wind.

One last engineering matter involved the strong electrical jolts that can occur when sprays of salt water land in places where iron connects to copper. In effect, the Statue of Liberty has the potential to be a 151-foot-tall battery. To prevent it from generating electric currents, workmen had to slide fabrics covered with red lead or made of asbestos inside the iron/copper joints. (Asbestos was banned from construction only in the late twentieth century.) Marine architects had used the same technique in building ships with huge metal hulls.5 Had Eiffel’s genius found a way to harness the statue’s electricity-generating power, the lighting problem that long plagued Lady Liberty might have been solved!

If the support structure required engineering brilliance, constructing the gigantic copper sculpture called for extraordinarily careful calculations, an army of highly skilled craftsmen, and the ability to manage the transformation of a four-foot model into a 151-foot colossus. Bartholdi organized the enlargement in three steps. First he magnified the original model into a plaster statue nine feet tall. Then he enlarged that by a factor of four, producing a new plaster model thirty-six feet high. The final step involved another fourfold enlargement to Liberty’s full size. The actual monument was so huge that Bartholdi had to produce this final enlargement by dividing the thirty-six-foot model into dozens of sections and then magnifying each of them one by one. This process required nine thousand painstaking measurements for each section and a battalion of expert craftsmen. Bartholdi’s men could work on only a few sections at a time, since their workshop, big as it was, couldn’t begin to accommodate the entire jigsaw puzzle that Liberty had become. In theory, each enlargement should have been identical to the original, except of course for the difference in scale. But scale mattered, and the magnifications altered the statue’s visual effects. Bartholdi constantly had to make corrections, which meant that he was anything but an absentee architect.

His work was at once intricate and grandiose; it took place at the Gaget and Gauthier workshops (formerly the Monduit workshops) just outside what until 1860 was the northwestern boundary of Paris. Today, this area is ritzy and upper class, distinguished by the elegant Parc Monceau. In the late nineteenth century, the Gaget and Gauthier workshops stood on a no-man’s-land between the city and the suburbs that was home to a chaos of warehouses, factories, and makeshift structures. Both geographically and psychologically, it was a long way from the well-kept neighborhoods of central Paris, where Bartholdi lived. Still, as the Statue of Liberty began to rise above the squat rooftops of the city, it became a major Parisian curiosity, and a great many people came to see it.

Honoré Monduit and his successors Gaget and Gauthier employed more than six hundred highly skilled artisans, who embodied the best traditions of French craftsmanship passed down from the Middle Ages. Before devoting nearly full time to the Statue of Liberty, the Monduit workshops did high-quality decorative work for the restoration of the Sainte-Chapelle and Notre Dame cathedrals. Monduit also helped craft the dome for Charles Garnier’s splashy opera house, commissioned by Napoleon III and completed just as the Statue of Liberty had begun to take shape. Before bringing in Eiffel as his main engineer, Bartholdi had worked with Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, himself famous for restoring several of France’s most notable castles and cathedrals. Although Viollet-le-Duc didn’t see the project through (he died in 1879), he influenced the design and conception of Bartholdi’s statue.6

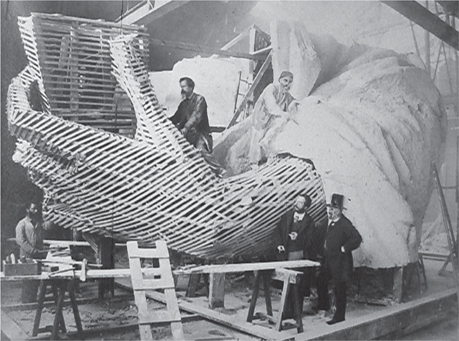

Never a modest man, Bartholdi knew that his construction project represented history in the making, and he and the photographer Pierre Petit made an elaborate pictorial record of each stage in the process. These photographs allow us to see exactly how the sculptor and his craftsmen built the Statue of Liberty. In addition, an article in the French engineering magazine La Génie Civile (1883), for which Bartholdi likely gave detailed information, explained the technical particulars of the construction process. The first step was to create a wood frame for each section of the statue. Craftsmen then plastered the frames to produce an exact replica of each full-size piece. Petit’s photographs show pygmy-like plasterers engulfed in a hand or overwhelmed by the scale of the torch or the head. Once plaster versions of each piece had taken shape, workmen undertook the difficult, intricate task of making wood impressions of them. Plaster had to give way to wood, because plaster couldn’t withstand the thousands of hammer blows integral to the process of sculpting thin copper sheets. So, each section began with a wood skeleton around which workmen fashioned a plaster model, whose purpose was to provide the form for shaping the necessary wood molds. The final stage in the process involved placing copper sheets, each three to nine square feet in size, on the wood molds and then using large wooden mallets to make them conform to the mold. On sections of the statue with elaborate curves, the copper sheets had to be heated to give them the flexibility required.

Plasterers building Liberty’s left hand and tablet. (© Collection Musée des arts et métiers [CNAM], Paris/Fonds Bartholdi)

Once the copper sheets had been beaten and fired into shape, workmen carefully extracted them from the molds. The last thing they wanted was to distort the forms they had so painstakingly created. Still, as an added precaution, Bartholdi used the plaster models to shape easily malleable, wafer-thin lead sheets into the form of Liberty’s skin. He then had his craftsmen press the molded copper sheets onto the lead ones to smooth out any remaining roughness and ensure that the copper conformed precisely to the plaster molds. Since no copper sheet was wider than about four and a half feet, several had to be joined together to produce the completed copper skin for each section of the statue. To keep track of all the sections, molds, and copper pieces, workmen carefully numbered and catalogued every one of them so that those who ultimately erected the Statue of Liberty would know how each piece of the puzzle fit together. By the end of this process, Gaget and Gauthier had produced three hundred separate pieces of Liberty’s copper skin. Together they weighed 88 tons (176,000 pounds), which, with the 132-ton iron skeleton, made for a colossus of 220 tons.

The mammoth task of building the Statue of Liberty stretched over eight years, from 1876 to 1884. The statue’s size and scale, plus the unprecedented techniques and craftsmanship involved, had attracted enormous attention in the press, as had the five-year-long fund-raising process. As a result, virtually everyone in France, and especially Parisians, could not help but be familiar with the project—all the more so after Bartholdi prominently displayed its head during the Paris International Exposition of 1878. Parisians would have been hugely disappointed not to see the finished product, and Bartholdi had always intended that they would. In the summer of 1882 Gaget and Gauthier began assembling the pieces already completed and undertook the task of putting the entire statue together, as if a gigantic Erector set. Again, a series of startling photographs document the process: first the central pylon, then the secondary parts of the inner structure. Before long, Parisians could glimpse the statue itself taking shape, as workmen began to hang the copper skin on its iron frame.

Liberty’s main pylon and secondary structure. (© Collection Musée des arts et métiers [CNAM], Paris/Fonds Bartholdi)

Liberty going up in Paris. (© Collection Musée des arts et métiers [CNAM], Paris/Fonds Bartholdi)

In Liberty’s metal girders, Parisians caught a foretaste of the Eiffel Tower, destined to rise just a half-decade later. But with the tower as yet unbuilt, Bartholdi’s statue became the French capital’s tallest structure. It drew everyone’s attention, and when finished, the scaffolding partly dismantled to reveal the head and torch, Liberty Enlightening the World loomed high over the seven-story buildings of Haussmann’s Paris. Although widely disseminated at the time, the photograph showing the Statue of Liberty against a Paris backdrop may seem disorienting today to Americans and others accustomed to the monument as a fixture of New York Harbor.

On February 1, 1884, Bartholdi told Richard Butler, chair of the American branch of the Franco-American Union, the so-called American Committee created to raise funds for the pedestal, that the statue was almost done and that he would let it stand in Paris until at least July 4. On Independence Day, he would officially present the French people’s gift to the U.S. ambassador in France. Throughout the spring and fall of that year, many distinguished people from around the country paid the statue a visit. President Jules Grévy gave it his country’s official recognition in early March, and a half-year later the legendary eighty-two-year-old Victor Hugo saw Liberty in what proved to be the last outing of his life. Afterward he wrote, “I have been to see Bartholdi’s colossal . . . statue for America. . . . It is superb. When I saw the statue I said: ‘The sea, that great tempestuous force, bears witness to the union of two great peaceful lands.’” Bartholdi had invited his mother and several of his financial supporters to observe the poet’s encounter with Lady Liberty, and the banker Henri Cernuschi commented, “I see two colossuses who take each other in.”7 The sculptor gave Hugo a fragment of the statue as a memento, and he later wrote the American ambassador, “Our illustrious poet had tears in his eyes, as did my mother; in short, everyone was deeply moved.”8

In part, they were moved by the thought of dismantling the statue and having it sent away. Over the previous year, Parisians had become accustomed to its looming presence and to its patriotic and republican symbolism. Many in France wanted it to stay. As the journalist Claude Julien wrote, “It is not without a profound regret that we will see it go. Our patriotism has dreamed of it elsewhere than on the other side of the ocean. We would have liked to see it on the crest of the Vosges, as a memento and a promise, as a response to the Germania of the Niederwald [the 130-foot-tall sculpture commemorating the new German Empire]. To this monument inaugurated by monarchs, the Statue of Liberty would have stood in reply as symbol of republican France.”9 Julien concluded by asking that Bartholdi build another Statue of Liberty for France, which he would eventually do, though at one-quarter of the original’s size. This replica, a gift from the American community in Paris to the French people, now stands on a small island in the Seine.

If Liberty represented French patriotism before it stood for the United States, French writers also understood “Liberty Enlightening the World” as an expression of their country’s scientific and technical prowess, as symbolizing a resurgent and newly confident people who had overcome the military and political humiliations of 1870–71. Bartholdi had shown, wrote André Michel, that France measured up to the world’s other great industrial powers and that the country was capable of a “male and noble talent” in science and engineering. France, he said, should not be defined in terms of the female “seductions” of impressionism, “the pretty approximations, the pleasant negligence” of a form of painting temporarily à la mode. Bartholdi’s work, by contrast, exhibited a host of male virtues: it was “frank and decisive,” “sincere and precise,” “profound and durable.” Since the disaster of 1871, a great many French commentators had fretted over their country’s apparent loss of virility in relation to the Germans. At the beginning of the century, Napoleon had thrashed both the Prussian and the Austrian armies; sixty-odd years later, the Prussians turned the tables on France. It’s ironic that Bartholdi’s sign of a renewed French manliness took a neoclassical female form, but, for writers like Michel, what counted was Bartholdi’s virile persistence against all the odds and the engineering genius that had allowed his statue to take shape.

As Julien and Michel expressed the French attachment to Bartholdi’s work, others doubted that the Americans would appreciate it. “Our Americans,” commented an editorialist for Le Quotidien, “are too practical to be enthusiastic, like the French, over seeing the Statue of Liberty. Their god is the dollar.”10 One reason for such French negativity stemmed from the apparent U.S. disinterest in accepting Bartholdi’s gift. Such, in any case, was the way numerous French writers interpreted the slow pace of the New York fund-raising campaign for Liberty’s pedestal. Bartholdi himself expressed disillusionment over what seemed lukewarm U.S. interest in his completed colossus. One reason he kept it standing so long in Paris turned on the lack of money for its pedestal—which the Americans had agreed to finance—in New York.11 Bartholdi waited until early 1885 to begin dismantling the Statue of Liberty from its Paris perch. His workmen packed it into 212 crates, each so heavy that together they required seventy boxcars and sixteen days for the trip to its Normandy port. From there the steamer L’Isère took all the pieces to New York. In its lone contribution to Liberty’s cost, the French government paid for shipping it across the Atlantic. Once unloaded on Bedloe’s Island, the crated statue sat, unopened, for nearly a year.

In 1877, the U.S. Congress had passed a bill agreeing to locate the Statue of Liberty on Bedloe’s Island and to accept responsibility for its pedestal. Congress did not, however, appropriate any funds for this purpose. The statue’s American backers had to finance this part of the project; they did so by creating the American Committee of the Franco-American Union, designed as the sister organization of its French counterpart. The American Committee’s efforts didn’t go very well. But New York group nevertheless organized an architectural competition for the pedestal and awarded the commission to Richard Morris Hunt, the first American of his profession trained in Paris at the Ecole des beaux-arts. Hunt was the best-known contemporary architect in the United States, and Bartholdi had sought him out during his initial U.S. voyage in 1871.12 As a long-standing member of the Union League Club, Hunt belonged to the liberal, Europhile establishment that had championed the Liberty project in New York and Philadelphia. He had designed homes and offices for its leaders and, in general, for the East Coast’s moneyed elite, including Joseph W. Drexel, the wealthy Wall Street banker who later headed the American Committee.

While Hunt worked on his plans for the pedestal, the project’s civil engineer, Charles P. Stone, began excavating the foundation to which the pedestal would be attached. Stone had worked for Khedive Ismail in the late 1860s, exactly when Bartholdi had tried to sell the Egyptian ruler on his lighthouse project for the Suez Canal. On Bedloe’s Island, Stone left nothing to chance. He sunk the pedestal’s foundation to a depth of thirty feet and situated it in the center of a solid pyramidal fortress that had long dominated the tiny speck of land. At its bottom, the foundation measured ninety-one square feet, tapering to sixty-five at the top, where the pedestal would be attached. Together, the foundation and pedestal would slightly exceed the statue in height—153 feet, compared to almost 152 for Liberty herself. For both the foundation and pedestal, Stone and Hunt used twenty-seven thousand tons of concrete reinforced with steel girders just inside its walls. Connected to those girders were huge pairs of triple steel I-beams, which yoked the foundation, pedestal, and statue so firmly together that the builders claimed the only way to topple the ensemble would be to yank the entire island up from its roots.13

For Hunt, the pedestal represented several challenges. It had to be grand and monumental enough to fit with the colossal size and ambition of the statue it was to support. But it could in no way overshadow or diminish Bartholdi’s monument. The pedestal thus needed to be a distinctive piece of architecture in its own right, while simultaneously drawing the viewer’s eye up and away from itself and toward what sat on its roof. Hunt’s initial designs failed to achieve this difficult balance; he had sketched a pedestal that was too elaborate and grandiose. The problems stemmed from the model he had used: the Pharos (lighthouse) of Alexandria, built on tiny Pharos Island between 280 and 247 BC and long one of the seven wonders of the ancient world.14 Like Bartholdi, Hunt found himself inspired by ancient Egypt; had the French sculptor built his colossus for the Suez Canal, Hunt’s initial designs might have produced an ideal pedestal for it. One key problem, though, was that the Pharos of Alexandra served not to support another, more important, structure, but rather stood as an architectural wonder in its own right. A small statue of Poseidon did cling to the Pharos’s top during the Roman period, but the “pedestal” overwhelmed the statue, which seemed essentially a decorative afterthought to a building designed to light the harbor for incoming ships.

Richard Morris Hunt’s Liberty pedestal.

Hunt obviously understood that the Statue of Liberty was to be the most important structure on Bedloe’s Island, and when he eventually reduced the pedestal’s height and width, its proportions complemented rather than diminished the sculpture on top. Still, by retaining the Pharos-inspired Doric columns, arched opening, protruding disks, and coarse, rustic blocks, Hunt avoided an architectural neutrality unsuited to the project at hand. That neutrality belonged to the straightforward, pyramid-like foundation, which Hunt’s pedestal linked to the monument as a whole through an ingenious combination of simplicity and grandeur.

By August of 1884, with the foundation well under way, Hunt’s revised design had been approved, the pedestal ready to go up. The Statue of Liberty, as Parisians knew firsthand, was ready as well. But Hunt, accustomed as he was to commissions for Fifth Avenue mansions and elaborate “cottages” in Newport, Rhode Island, faced a novel situation. He had no one to pay his bills.