Can I see the real me?

The powerful influence of self-beliefs on motivated behavior

The centrality of the self is a compelling and powerful motive that influences our day-to-day decisions and choice. The self is embodied in a series of values, goals, and social standards that inform and direct individual effort. Behavior is subservient to the dominant motive of the self, which is designed to create or improve positive self-concepts in relation to significant others. This chapter examines the variability of idiosyncratic and interpersonal motives grounded in self-worth perceptions that drive self-enhancing and failure-avoiding behavior. Individual differences related to social acceptance, compliance, obedience, altruism, and group dynamics are discussed. Additionally, the chapter reviews the self-protective strategies individuals employ to insulate themselves against the demoralizing prospect of believing they possess insufficient resources to meet learning and performance goals.

Keywords

Self-views; self-handicapping; social desirability; self-worth; altruism

Can you see the real me, preacher?

Can you see the real me, doctor?

Can you see the real me, mother?

Can you see the real me, me, me?

Peter Townshend

The rock band the The Who were onto something when they chanted the lyrics to the song The Real Me as part of the 1973 classic rock opera Quadrophenia. The psycho-dramatic theme of the album, and of the subsequent movie, was about the tribulations of establishing a social identity during the turbulent 1960s in Brighton, England. The story featured the adolescent exploits of Jimmy Cooper, a rebellious and indifferent lad, who was painfully searching for his personal identity among four different and conflicted personalities, none of which satisfied his alienated desires and troubled mind. Unfortunately, Jimmy and songwriter Townsend were operating under the misguided impression that individuals are able to precisely articulate and accurately determine the unique psychological characteristics that comprise identity. As we know from Principle #5 (p. 12), individuals are especially prone to misinterpreting their own motives and frequently cannot accurately describe their cognitive processes (Nisbett & Wilson, 1977). In turn, bias sometimes distorts behavioral meaning due to an overwhelming desire to portray the self in socially acceptable ways (Hyman & Sierra, 2011). Perhaps, the more relevant question for Jimmy Cooper, Peter Townshend, and the aspiring motivational detective (MD), is “Can you see the real you?”

To decipher the real you, or to “find oneself” (Baumeister, 1987, p. 163), is a process that starts with an introspective and evaluative examination of the beliefs, values, and standards that orchestrate behavior. The self is broadly defined as who we are, a personal representation, symbolic of our underlying motives, which represent purpose, characteristics, interests, and idiosyncratic attributes that comprise the totality of our being. The ability to describe and understand the self is grounded in a self-awareness that enables the individual to understand why certain goals are selected and pursued and why we choose to reach our goals using particular strategies. Self-awareness implies that we have the ability to discern the difference between the external self that we elect to divulge publically through visible action, compared with the often clandestine and social self, which we may deliberately choose to obscure or share only selectively with others (Schlenker, 1980).

Ironically, realizing self-awareness and shaping self-representations many times involve a series of introspective and analytical evaluations based upon our relationships, interactions, and comparisons of ourselves to others. Considering that the primary function of the self is to gain social acceptance and enhance social position within desired in-groups (Baumeister, 2010), individuals frequently become highly susceptible to social influence. The slightest indication that certain people will be present, either physically or virtually, to observe or evaluate our actions may cause a radical shift in our behaviors and even change the way we think (Dunning, 2011). As a youth, before making an important decision, you may have been advised to ask yourself, “What would I do if my mother were watching?” as a conscientious check on impending action. Although a maternal conscience may not guide your adult actions, every day we make many significant implicit and explicit evaluations of who we are and how we elect to portray ourselves in comparison with the expectations and ideals of significant others, desired in-groups, and affiliative cultures.

At any given moment, we may consciously choose to modify our external self. Faced with the prospect of engaging with one particular peer group, we may choose to be talkative, optimistic, and helpful, while in another setting we may elect to send a different message and intentionally decide to be inflexible, contrarian, or aloof, based merely on group composition or the specific impressions and reactions we wish to generate from others. Our public face applies to virtual arenas as well, as individuals frequently elect to express different facets of their personas, with variations in exhibited traits contextually determined by the type of virtual environment encountered (Childs, 2011). The changes in how we think and behave when alone versus under the influence of others are so pervasive that psychometricians have designed and validated instruments, such as the Predictive Index (Harris, Tracy, & Fisher, 2011), which measure differences between the qualities that individuals expect or believe they should publically exhibit, as opposed to their actual behaviors. Measureable differences are usually observed, solidifying the contention that individuals calibrate their own behaviors based upon a set of measurable standards determined and expected by others.

Consequently, attaining an accurate and realistic self-portrayal is a complicated, challenging, and potentially stressful process because “nearly every action can carry a social meaning that has implications for what a person is like and how he or she should be treated” (Schlenker, 1980, p. 5). Individuals develop a “relational self” (Brewer & Gardner, 1996, p. 83) that dictates how we want to be perceived. Once the relational self is affirmed, individuals engage in evaluative comparisons of the self to the preferred set of cultural standards or in-group norms, hoping to voluntarily fit in, or alternatively, deliberately stand out. By example, motivational leaders Alec Torelli and LaSonya Moore specifically rebuffed stereotypical standards, setting themselves apart from their peers. LaSonya consciously rejected the typical consequences of having a child at a young age and relying upon social programs for financial assistance. She stated that one of her primary motives was to escape the “hood” at all costs. Alec Torelli mentioned disdain for Tourney Pros, who, in addition to craving poker winnings, are highly motivated to developing glamorous television images to secure sponsors, generate publicity, and increase personal notoriety. LaSonya and Alec deliberately elected to stand out, not fit in.

Individuals are motivated to attain consistency between their enacted and desired selves (Higgins, 1987). Psychological vulnerability, primarily in the form of anxiety and negative emotions, results when individuals realize that their actual self is discrepant from their desired self. Unfavorable discrepant self-evaluations often result in feelings that the self is incompetent, insincere, inconsiderate, phony, thoughtless, and unattractive (Baumeister, Tice, & Hutton, 1989). In extreme cases, self-discrepancies result in dramatic self-esteem deficits and may lead to clinical depression (Sowislo & Orth, 2013). Paradoxically, those who best know the self may suffer as heightened self-awareness may contribute to the development of a chronic discrepancy fixation. This sardonic consequence of effective introspection promotes sarcastic and negative ruminations. Author Kafka claimed, “I have the feeling of myself only when I am unbearably unhappy,” while occasional celebrity Courtney Love caustically proclaimed, “Only dumb people are happy!” suggesting that a lack of self-awareness is, indeed, a blessing in disguise.

When applying the paradigm of self-awareness to evaluating the superiority of their academic fortunes, individuals are faced with a comparative dilemma. They can associate their most current achievement with their own past performance, identify an objective mastery standard, such as a learning target, or compare themselves to another person deemed similar in ability or temperament. Chapter 4 discussed the developmental trajectory of social comparisons and identified two primary reasons why individuals elect relational benchmarks. First, individuals may not have sufficient experience or past performance or may lack available or understandable task-relevant data to make informed comparisons with a standard of mastery. Second, individuals may be highly motivated to make positive comparisons with others as a means of attaining a self-serving ego boost (Wheeler & Suls, 2005). A third viable explanation for person-to-person appraisals suggests that social comparison fosters positive self-evaluation and serves as a way to validate personal capabilities against societal norms (Buunk, Groothof, & Siero, 2007; Festinger, 1954). In school, many social comparisons are motivated by the desire to fit in with emerging peer groups, which potentially contribute to affirming positive self-images based upon group inclusion (Alderman, 2004). Organizationally, social comparisons serve as a barometer to calibrate and justify leadership styles, set performance standards, and establish organizational norms for social behavior (Greenberg, Ashton-James, & Ashkanasy, 2007), which subsequently helps individuals successfully assimilate within an organizational culture.

Social comparisons are broadly categorized as either upward or downward in trajectory. Upward comparisons can provide useful information for positive self-enhancement (Mussweiler, Gabriel, & Bodenhausen, 2000), suggesting that the individual is motivated by self-improvement, enticed by the prospect of attaining the skills and abilities of a viable and respected behavioral model, perceived to have similar characteristics to the individual (Buunk et al., 2007). Upward comparisons are motivationally adaptive because the individual strives to improve, such as when academically aspiring to earn better grades, or to master content. Upward comparisons are more productive when undertaken anonymously, as individuals are able to physically insulate themselves from the evaluation of others, who, if physically present, may potentially ascribe skill deficits or inferior ability to the individual (Ybema & Buunk, 1993).

Downward comparisons are self-protective and are typically undertaken by individuals lacking the necessary confidence to make upward comparisons, by persons with lower levels of self-esteem, and by those who are worried about what others think of them. Individuals with a downward comparison trajectory tend to have inflated perceptions of their subjective well-being because they believe they are better off in comparison with others (Wills, 1981). The downward comparisons generate positive affect in many individuals because of the presumption that others are more disadvantaged than the individual making the downward comparison. Ultimately, the feeling of superiority enhances the self-esteem of the comparative beneficiary. The phenomenon of downward comparison is especially striking for individuals suffering health complications (Tennen, McKee, & Affleck, 2000). For instance, individuals who perceive themselves as better off than someone else (or who believe that someone else is more ill), independent of physical disability, report higher overall subjective well-being (Buunk et al., 2007) and have greater reductions in the severity of health problems following cancer (Eiser & Eiser, 2000).

The physical, emotional, and cognitive reactions to social comparisons are of critical importance to MDs. Considering that individuals frequently base their self-evaluations on their perceived degree of fit and alignment with significant others, self-esteem and corresponding self-worth contingencies develop during the evaluation process. Individuals will tend to appraise their degree of competence not entirely based upon actual ability and knowledge but will, instead, make personal capability evaluations based upon the presumed competency beliefs others ascribe to the individual. Covington (1984) suggested that evaluation of self-worth is a consequence of academic cultures because competitive academic environments contribute to the self-evaluation of attributes needed for classroom success, primarily realized through ability assessments. According to Covington, “perceptions of ability are critical to the self-protective process, since for many students, the mere possession of ability signifies worthiness” (p. 4). Individuals will naturally tend to seek out environments that generate positive self-esteem, which, in turn, promotes improved perceptions of self-worth. Academic and workplace performance arenas are high-stakes for many individuals. Who we are and the general conception of our competency is based, in part, on instigating outcomes deemed of value to others. As a personal motive, the perception of positive self-worth alone should be a catalyst directing individuals toward performance tasks at which they have a probability of being successful while steering clear of those targets deemed overly challenging or having a high probability of failure.

Unlike the previously discussed motives related to historical attributions and prospective self-efficacy evaluations (Chapter 6, p. 139), the source of self-worth assessments and corresponding competency beliefs does not originate solely from observed results. Criteria-based outcomes are important but are primarily relevant from the perspective of how they are perceived. Many times, individuals stake their self-evaluated academic reputation and their mirrored reputation by others based not upon what they accomplish but on reactions to their achievements. Feasibly, two individuals can achieve identical results but reach entirely different conclusions about the suitability of the outcomes. One person may react positively, resulting in enhancements to self-worth, while the other person views the same results as frustrating and self-defeating, leading to negative ruminations and deteriorating self-worth perceptions.

The differential reactivity phenomenon is naturally observed when the skeptical and marginally competent learner earns a “B” on an examination when expecting a lower score. Emotions resulting from the “B” grade range from ecstasy to surprise, but the “B” outcome is positively perceived because it was better than expected, leading to elevated perceptions of self-worth. Conversely, when the overachieving peer earns the same “B” grade, the learner becomes fraught with anxiety. Perceptions of worthiness are decimated, not because of ability differences but because the overachiever expects more and emphatically stakes self-perceptions on academic ability. The potential that the grade may be perceived as relatively inferior, in light of his or her ability perceptions, threatens self-worth. Individuals not living up to their own expectations will experience feelings of guilt, shame, and humiliation, especially in highly vulnerable situations where substantial effort was expended but anticipated results were not achieved.

The coup de grâce, however, is not the academic outcome but the potential that the individual will evaluate and define his or her self based upon the observed results. Self-definition may usurp traditional logic, with worthiness anchored not upon knowledge or results, but on the qualitative consequences of forestalled achievement. Covington cautioned that “one’s first priority is to act in ways that minimize the implications of failure, namely, that one lacks ability” (1984, p. 8). Thus, to maintain a positive self-image, individuals will go to great lengths to insulate themselves from threats to self-worth. When individuals perceive a threat to positive aspirations of self-worth, they tend to engage in a series of strategic failure-avoiding manipulations. The strategies are designed to deflect any possible inferences concerning ability and concurrently avoid deterioration of self-worth perceptions. In the words of Covington, “students are likely to choose—if choose they must—to endure the pangs of guilt rather than the humiliation of incompetency” (1984, p. 11). Guilt results from the pain of avoidable failure, while humiliation occurs when invested effort reaps few rewards, promoting anxiety and trepidation based upon the presumption that significant others may believe the individual lacks sufficient ability to succeed. To avoid the stigma of inferior ability, individuals will protect their self-worth perceptions by shifting blame for failure to external or uncontrollable causes, such as downplaying the significance of results or criticizing test integrity (Covington, 2009). The individual assumes little or no responsibility for results, leaving positive self-worth intact.

At least three conclusions can be drawn from the powerful influence of self-worth perceptions. First, individuals change behaviors based on others, and many exhibit a strong proclivity to look good in the vantage of the admirer’s eyes. Second, individuals react differently to undesired outcomes, notwithstanding absolute results, because of the consequence of the outcome on self-evaluations. Third, people actively strive to insulate themselves from disparaging and negative self-worth perceptions by engaging in a variety of failure-avoiding strategies. However, the exact influence of other people, the consequences of individual self-worth differences, and the unique set of strategies that individuals use to fortify positive evaluations are of great concern and thus discussed next.

Principle #40—The psychological or physical presence of others may alter normative behavior

Many classic studies in social psychology reveal how the presence of others influences our personal perceptions and the behaviors we are willing to demonstrate in public. In the seminal conformity study, Asch (1956) asked experimental subjects (research study participants) to compare two sets of geometric lines for accuracy of length. Under the influence of a group of disagreeable confederates (people knowing the actual purpose of the study), subjects repeatedly agreed to obviously wrong answers when comparing a shorter line to a supposedly similar, but actually much longer line. The study illustrated how individuals will knowingly make judgments in contrast to their own personal beliefs and conform to normative behavior based upon suggestions from others. The classic Milgram obedience experiments (1963) revealed that individuals can be pressured into giving another person what appeared to be painful electric shocks of escalating voltage, merely at the suggestions of an authoritative source, in this case a researcher wearing a lab coat. During the experiment, 65% of study participants obeyed the researcher’s instructions and were willing to deliver what they believed were 450-volts electric shocks to a study participant who did not correctly recall a specific word in a staged memory experiment.

The presence of others can also tragically result in behavioral lethargy or failure to act. The most salient example of collective apathy is the horrific story of young Kitty Genovese, who, in 1964, was brutally assaulted and raped in an apartment courtyard within earshot of 38 witnesses. Upon questioning from the police immediately after the crime, witnesses indicated that they did not call the police because they expected that someone else would make the call. The phenomenon of inaction resulted in coining the infamous bystander effect (Latané & Darley, 1970), which contends that individuals are more willing and likely to offer help when alone, than when part of a group. While some accounts of the Genovese murder were blamed on pluralistic ignorance (Latané & Rodin, 1969), no witness indicated withholding help specifically because of conflicted Samaritan beliefs or due to lack of a presumed obligation to help another person in distress. Instead, enacted behavior was discordant with individual beliefs and blamed on the social influence of others. Although the specifics of the Genovese case are sometimes disputed (Manning, Levine, & Collins, 2007), the general inferences are not; people act differently when others are watching.

The seminal examples described here suggest that individuals are vulnerable to a variety of social and contextual influences and may exhibit certain thoughts and actions contrary to personal beliefs and private behavior. The theories of planned behavior (TPB) and reasoned action (Ajzen, 1991) contend that individuals evaluate their beliefs and attitudes as a prelude to motivated action. Further, TPB indicates that behavioral intentions are mediated by socially acceptable normative beliefs that modify an individual’s actions. Normative beliefs undergo scrutiny by the individual, whereby the person assesses the integrative and relative fit of the normative beliefs to their own personal beliefs and behavioral intentions. If the individual is of the presumption that his personal beliefs are weak compared with societal norms and the person believes he can exert control over a situation, social pressure will induce the person to follow normative patterns. In the absence of control, or when personal beliefs are deeply entrenched or strongly conflict with normative beliefs, there is reduced likelihood that the person will exhibit socially desirable behavior. In other words, societal norms and pressures can ignite or diffuse behavioral intentions, influencing behavioral direction and intensity based upon the commitment to one’s beliefs. Frequently, people yield to behavioral intentions that conflict with societal norms, resorting to the maxim of “go with the flow,” accelerating action based upon the intensity of societal expectations, lukewarm self-beliefs, and the prospect of feeling in control.

When subjected to excessive social pressure, individuals may display a variety of behavioral differences in public and private, primarily as a means of inducing approval from others and strengthening their public identities (Gollwitzer, 1986). The phenomenon of being easily persuaded by the external expectations of others and portraying the self in particular ways to foster social inclusion is termed self-presentation or the process of impression management, which dictates that individuals actively seek to elicit and control reactions from others (Schlenker, 1980). Personal control may provoke both positive and negative reactions in others based upon the individual’s behavioral intentions. If you have ever heard the words, “Are you trying to start an argument with me?” or “What’s your problem?” you will quickly realize the power of impression management! Table 8.1 illustrates concrete examples from diverse domains where the presence of others is a catalyst that usually induces normative behavior, sometimes in contrast to, or despite the intensity of, one’s convictions or behavior patterns typically displayed when alone.

Table 8.1

Selected summary of empirical results supporting the influence of sociocultural norms on exhibited behavior

| Behavior | Effects of social influence | Evidence |

| Dieting | Girls begin dieting at younger ages. Norms instill more concerns about appearance resulting in greater body dissatisfaction. | Strahan et al. (2008) |

| Social eating | Social influences result in greater or reduced consumption based on type of host, group composition, gender, and observer type. | Herman, Roth, and Polivy (2003) |

| Health screening | Women are more likely to seek breast cancer screenings when supported by spouse, compared with no spousal support. | Steadman and Rutter (2004) |

| Aggressive driving | Level of aggressive teen driving significantly increases in the presence of peers or decreases based upon extent of parental involvement. | Prato and Kaplan (2013) |

| Public littering | People are more prone to littering when in the presence of other litterers. Dirt begets dirt. | Cialdini, Reno, and Kallgren (1990) |

| Academic participation | University students participate less in class because of fear of peer disapproval from other students accounting for large negative self-reported perceptions of participation. | Weaver and Qi (2005) |

| Gratuities | Patrons give higher tips to servers when the server compliments the patron and when the patron seeks social approval from the server. | Seiter (2007) |

The contingencies related to how individuals exert influence on others transcend behavior. The psychological or physical presence of others motivates change not only in the public domain but also in how we respond to and feel retrospectively about the behaviors we exhibit. The self-assessments generated by the qualitative and affective assessments of our successes and failures are frequently labeled as the degree of self-esteem we possess. Self-esteem is generally conceived as a personality variable (Brown & Marshall, 2006) that influences our ascriptions of overall self-worth. Self-esteem describes the personal evaluations of the self in relation to others or to a set of arbitrary values that are determined by our relationships, contexts of application, or culturally-determined normative standards. The resulting assessments are self-evaluations, or judgments, of our accomplishments that either produce satisfaction or promote disenchantment based upon the subjective appraisal of outcomes in comparison to expectations. While researchers debate whether self-esteem is the cause or the result of self-evaluations (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001), positive assessments elevate levels of self-esteem, while negative evaluations decrease self-esteem. Ultimately, these self-judgments lead to appraisals of self-worth, and many researchers use the terms self-esteem and self-worth interchangeably (Crocker & Wolfe, 2001).

Self-evaluations may correspond with prosperous emotions, such as feelings of fulfillment, elation, and pride, after a positively evaluated achievement, while not meeting self-expectations may lead to feelings of disappointment, shame, guilt, or humility. Ascriptions of self-worth are personal and quite arbitrary, as it is not the event, per se, that determines self-evaluation valence, but the reaction to the event. For instance, Alex Dixon correctly recalling a word when searching the recesses of her vocabulary may be a strong source of satisfaction leading to positive self-esteem, while the same phenomenon for eloquent speaker Nick Lowery would be inconsequential and effectively esteem neutral. Thus, we can infer that self-esteem is grounded in a foundational assessment of our own perceived capabilities, in relation to our anticipated potential. Although assessments are relative to the individual, we should recognize that individuals higher in self-esteem frequently set more challenging goals, have stronger expectancies of goal attainment, and exhibit a higher commitment toward attaining their goals (Hollenbeck & Klein, 1987; Hrabluik, Latham, & McCarthy, 2012).

Self-awareness and degree of self-view positivity are the primary psychological distinctions between individuals described as possessing high self-esteem (HSE) in comparison with low self-esteem (LSE) (Campbell & Lavallee, 1993). Individuals with HSE show consistency and clarity of beliefs characterized by expectations of task-based success, as opposed to LSE individuals who are skeptical of their abilities and uncertain as to what actions would promote successful outcomes (Tice, 1993). Subsequently, the HSE individual seeks ego-inflating opportunities that, if mastered, enhance impressions of self-worth. Consequently, the LSE person will deliberately avoid opportunities that have the potential to result in failure instead taking solace in choosing more conservative and cautious endeavors, exhibiting a self-protection motive and thereby avoiding the risk of possible humiliation or social rejection.

A crucial aspect of the HSE–LSE distinction is manifested in appraisals of ongoing self-worth based on task-based experience. Early life experiences in performance domains, such as athletics, socialization, or academics lead to self-assessments and corresponding evaluations of self-worth. Many times, children will experience early-life emotionally laden triumphs and challenges that expose the child to contextually driven and unsolicited socialized feedback, presumably from parents, caregivers, and teachers. When experiencing success, the developing child hears encouraging remarks, such as “Great effort!” or “Fantastic job!” or “You’re the best!” Failure to reach performance goals is met with optimistic reassurances, such as “Try harder,” “Don’t give up,” or “You will improve,” to deflect the negative emotionality of falling short of one’s goals. These basic task-contingent evaluations contribute to self-identity formation and eventual self-competency conclusions that contribute to evaluations of self-worth in relation to specific tasks. The spiraling evaluation process is recursive and perpetuating as Brown and Marshall (2006) succinctly described:

When low self-esteem people encounter negative feedback their self-evaluations become more negative and their feelings of self-worth fall. When high self-esteem people encounter negative feedback they maintain their high self-evaluations and protect or quickly restore their feelings of self-worth (p. 7).

Eventually, the certainty of emotions aligned with particular tasks becomes cumulative, either forestalling or encouraging future task engagement. The probabilistic emotion supersedes the usual satisfaction of task completion, resulting in either avoidance or shallow task commitment by the LSE individual. Conversely, the HSE person is more resilient and willing to try harder, not easily discouraged from attempting the most challenging tasks, even when suffering humiliation (Baumeister & Tice, 1985).

But the rosy profile of the HSE individual bears many thorns. The relation among elevated levels of self-worth and work performance or academic achievement is, at best, ambiguous (Baumeister, Campbell, Krueger, & Vohs, 2003). Little evidence actually supports the notion that HSE causes accelerated performance or results in learning gains. Individuals high in self-esteem may feel good about themselves, but they are also prone to having exaggerated views of the self. These views, predicated on ignoring important and relevant feedback, may hinder positive socialization and relationships, promote lack of self-regulatory skill, and lead to individuals inflating ability perceptions when skills may be lacking (Crocker & Park, 2004). Regardless of the potential liabilities for the HSE person, we can summarily conclude that normative and social factors exert an enormous influence on individual thoughts and behaviors. The question remains, however, as to why others exert such a tremendous influence on behavior and how MDs can harness knowledge of conformity and socialization to effectively cultivate motivated behavior. We next examine specific social influences and the behavior these influences may potentially cause.

Principle #41—Pro-social behaviors are compliant, adaptive, and predictable

The social affects described thus far suggest that the influence of others can, at times, be disturbing, self-defeating, and clearly inhibit self-determination. Evidence was presented that friends and strangers alike can inflict subtle or direct psychological control over our decisions, akin to manipulating us, despite our common sense, logic, or personal beliefs. The power of others is so pervasive that gullible humans will engage in risky and unhealthy behavior, tolerating danger and tempting fate, despite knowing the harmful consequences of their actions and the likelihood of disastrous outcomes. Motivated by the desire to enhance positive impressions and develop self-worth, individuals will risk skin exposure without sunscreen use, drive recklessly when with friends, be promiscuous and engage in unprotected sex, continue smoking to avoid weight gain, and participate in dangerous sports, such as extreme skiing, risking permanent disability or death, all in the name of admirable self-presentation (Leary, Tchividijian, & Kraxberger, 1994).

While the sordid side of influence cannot be denied, we are also inclined to exhibit a wide variety of supportive, industrious, and gratuitous behaviors because of others. The benefits of prosocial behavior whereby individuals and groups engage in a variety of helping and cooperative behaviors that are beneficial to others are enormous (Mussen & Eisenberg-Berg, 1977). Our culture abounds with iconic symbols of prosocial behavior, such as traffic lights, group discounts, online music swapping, and self-directed work teams that provide various incentives for us to socialize, collaborate, and work together. In the classroom, pedagogical methods, such as constructivism and guided discovery, are used to engage learners and leverage the positive motivational benefits of working together as a means to master learning and problem solving goals. The myriad of variables that influence prosocial motives and subsequent behavior are far too numerous to comment upon individually. Instead I examine why individuals across cultures will frequently offer unsolicited help to seemingly benefit others, volunteer their time and services, and categorically comply with a multitude of requests from arbitrary “superiors,” keeping in mind that exhibited behaviors and espoused motives may be a façade and not portray who we truly are or hope to be.

Prosocial behavior can be explained in many ways. Cialdini and Griskevicius (2010) suggested that individuals have innate needs to engage in goal-directed behavior. People prefer to attribute causality of outcomes to personal actions, not random events, and tend to realize an immense satisfaction when achieving desired results. From an evolutionary perspective, reaching premeditated goals is adaptive; During the goal attainment process individuals hone and regulate critical skills necessary for survival, ultimately enhancing personal longevity, if successful. Psychologically, goal attainment contributes to positive self-evaluations, solidifying public reputations and giving groups the impression of our value as a group member. Physiologically, prosocial behavior is especially significant among kin and for the perpetuation of one’s lineage, based on “promoting the survival of those who share your genetic make-up” (Kassin, Fein, & Markus, 2008, p. 347). Summarily, behavior supporting others provides social, collective, and cultural benefits.

Engaging in prosocial behavior is personally beneficial in at least three ways: (1) Being involved in the success of others satisfies our need for affiliation (Correll & Park, 2005); (2) helping others makes us feel good by elevating mood (Wegener, Petty, & Smith, 1995); and (3) assisting others affords us the social and materialistic benefits of group participation (Penner, Dovidio, Piliavin, & Schroeder, 2005). Collectively, these reasons suggest that one important motive for prosocial behavior is our own psychological prosperity; it boosts self-worth evaluations. Unfortunately, many times, awareness of prosocial motives may be unconscious and personally elusive (Penner et al., 2005), inhibiting a person’s ability to actually see the real “me.” The phenomenon of demonstrating effort to benefit others while actually helping ourselves is known as egoism (Batson, Ahmad & Stocks, 2011). Thus, prosocial behavior that may appear to be demonstrated for the service of others can actually be exhibited exclusively for personal gain. The egoism motive is especially instrumental when we are already in a good mood, serving the purpose of perpetuating the positive mood (Piliavin, 2003). However, we also tend to help others when we feel bad about ourselves because the process of helping often leads to a positive mood change and restoration (Carlson & Miller, 1987; Weinstein & Ryan, 2010).

Prosocial behavior manifests in a variety of ways. First, many individuals subscribe to the principle of reciprocity whereby individuals feel obligated to respond in kind when they believe others have helped them. The human consciousness is bound in the evaluation and integration of personal and sociocultural equity assessments. When someone does us a favor, we reciprocate. When a favor is unreciprocated, anger and tempestuous reactions may follow because most individuals believe in the restoration of social or materialistic inequity (van Doorn, Zeelenberg, & Breugelmans, 2014). I have mordant memories of inequities resolved during family feuds over the calculation of the appropriate amounts or the value of planned wedding or baby-shower gifts, based exclusively on what was received in a similar situation. Similarly, obligatory debt has social ramifications, such as when my daughter Rebecca accepted an iPod as a gift from a not-so-secret admirer who had hopeful expectations of receiving “something” in return. At times, we feel obligated to socially entertain friends or colleagues, after accepting a similar invitation. The obligatory trend to reciprocate transcends dyads and families, extending to strangers through indirect reciprocity. The spillover effect suggests that we are willing to do favors, be “nicer,” and help others we do not even know, provided that the person in need has been kind to a mutual friend or relative (Liang & Meng, 2013).

A second social influence whereby individuals are willing to comply with the requests of others, due, at least in part, to enhance positive self-impressions, is the consistency motive (Cialdini & Griskevicius, 2010). Consistency suggests that individuals have espoused values and beliefs that substantiate identity and contribute to the impressions we imprint on others. Consistency becomes important because uniformity of behavior implies commitment, loyalty, and stability, which are highly desirable human qualities (Bendapudi & Berry, 1997; Cialdini, Trost, & Newsom, 1995). Once a philosophical or behavioral commitment has been espoused, such as giving money to a worthwhile charity, consistency principles suggest we are more likely to demonstrate that type of behavior toward affiliated causes. My philanthropic girlfriend, Karen, once made the charitable gesture of donating $10 to an animal rights group, only to receive a barrage of mail order solicitations in the subsequent months, suggesting that she live up to her public commitment to animals by making additional donations to organizations purportedly designed to save dogs, cats, tigers, lions, horses, cattle, and whales. Many of these donation requests included nominal gifts, such as shiny coins, $2 US notes, calendars, address labels, flags, or t-shirts, hoping to take advantage of her admirable kindness by using the social obligatory motives described in the previous paragraph.

A third factor inducing prosocial behavior is individual responses to requests based on actual or purported power. Almost all societies are structured in social hierarchies. Leaders at the hierarchy apex are granted certain rights and privileges as a condition of leadership—advantages that are not readily offered to or assumed by subordinates. Leadership privilege connotes direct and indirect influence of one person on another. Compliance implies a purposeful expectation to complete an act under a controlling influence, such as when individuals acquiesce to supervisory demands. Responding affirmatively to a compliance request is oddly comforting for the individual because the correct response means that the individual has attained a proximal reality-based goal (as well as continuing employment). Conformity suggests that individuals respond to leadership direction, not by obligation, but based upon perceived norms, expectations, and indirect social influence (Cialdini & Goldstein, 2004). When capitulating to conformity, responses to leadership power are typically motivated in two ways: informational or normative. Informational influence suggests that the powerful other is an accurate and trustworthy source of information. People respond affirmatively to informational influence because the individual making the request is perceived as a qualitatively superior source of information, possessing greater knowledge than the uninformed or inexperienced individual conforming to the informational influence. Conformity under normative influence is motivated by social approval, as many individuals conform because they prefer to align with others and avoid the perception of social defiance, which frequently results in being ostracized for recalcitrant and uncooperative behavior, especially in organizations (Begley, Lee, & Hui, 2006).

Despite power hierarchies and conformity pressure, some individuals will dissent, dispute authority, be disobedient, and rebuff compliant behavior, but why? First, we should operate under the understanding that based upon contextual conditions, such as the proximity and strength of the conformity influence (Latané, 1981), individuals will situationally exhibit a range of behaviors from fully compliant to fully defiant. Recalling the classic Milgram experiment (1963), 35% of the participants ignored the researcher’s instructions to continue to shock the confederate with up to 450 volts of electricity and, instead, quit the experiment despite the researcher’s multiple stern warnings that stopping was not allowed. In the Milgram study, the experimental subject could not physically see (but could hear) the confederate actor grimacing in imaginary pain from the pretend shocks, thus lessening exposure. Second, the experimenter had a high degree of authoritarian strength that was intensified by wearing a lab coat. Although you may be skeptical that a lab coat or the social status of an individual can encourage people to give electric shocks, Bushman (1988) found that individuals are more likely to follow orders given by someone dressed as a security guard, compared with the same person being dressed in regular work clothes, even when the request has nothing to do with the security guard’s position (e.g., picking up garbage in the street). Third, Milgram’s groundbreaking experiment was criticized for some methodological imprecision that may have biased the results (Reicher & Haslam, 2011), suggesting that perhaps other explanations for disobedience are warranted and justified. Specifically, Reicher and Haslam proposed that social identity was a prevailing variable in dissention. Once individuals formed a relationship with another study participant, social pressure to dissent increased because the individuals wanted to be seen positively in the eyes of other participants, again suggesting that our own self-worth evaluations and how we want to be perceived by others are socially grounded and instrumental in mediating compliant and conforming behavior.

We can reasonably infer that individuals with deeply entrenched beliefs, high domain-specific knowledge, and HSE are more willing to reject normative behavior because of high ascriptions of self-worth. Pitesa and Thau (2013) studied espoused reasons for resisting and rejecting overtures of unethical organizational behavior. The researchers hypothesized that individuals who directed more attention to themselves and those who exhibited a “private self-focus” would be less likely to make unethical decisions. Self-focus was defined as “the attentional state of being aware of personal thoughts and feelings” (Fenigstein, 1979, p. 76). Individuals with higher “self-focus” paid less attention to work environmental factors and, instead, relied more heavily on self-perceptions to make their ethical decisions. The results of the study concluded that individuals using an introspective focus mediated the effects of power on behavior, suggesting that at a minimum, self-awareness and self-perceptions in relation to authority figures can radically influence organizational cohesiveness and behavior.

While knowing why people are socially responsive is one part of the MD’s challenge, application of that knowledge is highly useful. The practical aspects of how adaptive prosocial behavior impacts individuals is perhaps best illustrated by a workplace study conducted by Thau, Tröster, Aquino, Pillutla, and De Cremer (2013) who investigated how the leadership behavior of supervisors influenced employee self-worth perceptions and intergroup dynamics among co-workers. Thau and colleagues hypothesized that preferential treatment from supervisors led to employees initiating social comparison with co-workers, which ultimately influenced evaluations of their own self-worth based on perceptions of preferred comparative treatment. When supervisory treatment was manipulated, participants who were treated best rated their self-worth higher than those employees treated less favorably. In two related studies, preferential supervisor treatment predicted greater adherence to normative and desired organizational behavior (e.g., not stealing company property), as well as encouraging a greater willingness in employees to engage in gratuitous behaviors beneficial to others. In essence, a conscious and deliberate emphasis on variations of kind and considerate leadership style supported individual psychological growth and overall group cohesion. Additionally, the perception of better treatment from supervisors led to higher ascriptions of self-worth in the individuals. These findings suggest that it is possible to concurrently orchestrate contextual environments and influence self-evaluations that promote adaptive motivation, result in congenial behavior, and support the egoistic prosocial motives that are highly useful to promote cooperation in others.

Principle #42—Pro-social motives are egoistic and altruistic

Reflecting on the antecedents of cooperative behavior, it may seem that egoistic motives and self-satisfaction of psychological or materialistic needs underlie most instances of prosocial behavior. While an egoistic interpretation is frequently viable and accurate, the explanation is insufficient to explain the full spectrum of prosocial behaviors. Sometimes, we are specifically motivated to help others with no expectation of intended benefits in return. In these cases, individuals exhibit altruism, a special form of cooperative and gratuitous behavior, primarily motivated by “the expenditure of the self in the service of others” (Cavalier, 2000, p. 68). Altruism differs from other types of prosocial behavior because when motives are exclusively altruistic, personal needs become subordinate, suppressed, or deferred in order to satisfy the needs of others. Although frequently individuals receive egoistic benefits from instances of altruism, self-benefits are unintended consequences of the helping process (Batson et al., 2011). Altruistic motives are endemic to many professions where people, sometimes referred to as “superheroes,” regularly exhibit self-sacrifice for the benefit of others. Individuals demonstrating unadulterated altruism run into burning buildings, spontaneously perform Samaritan acts, or potentially risk their own psychological harm while helping those less fortunate or in need, such as the frequent challenges experienced when working in the first responder, medical, or teaching professions.

One such person is country music star Jessi Colter. Although not a doctor or teacher, from an altruistic perspective Jessi is a prototypical model of someone who forestalled personal gain to unselfishly help others. Like many family matriarchs, Jessi elected to devote much of life to her husband and now is dedicating her time, partly, to helping her son be as successful as possible. Considering that Jessi was married to country music pioneer and icon Waylon Jennings for over 30 years, the evidence speaks loudly in her favor. Jessi indicated, “I believe that you live so that others can believe in you. It starts by asking yourself, how can I help in this situation?” (J. Colter, personal communication, August 15, 2014). Jessi downplayed her persuasive abilities and her personality is notably reserved and highly spiritual, but she readily admitted that helping others starts with leading by example. Despite her reserved nature, many people give Jessi credit for keeping her superstar husband alive through turbulent times while navigating the pitfalls of fame and fortune. She described the challenges of resisting hedonistic temptation that often occurs when traveling on the road 300 days a year. Several times, she stressed the importance of stability and commitment to one’s own self-values as the key to leading a fulfilling life and being able to give unto yourself in the service of others.

It may be difficult to tell from Jessi’s brief biography what really matters to her. Jessi exemplifies the empathetic style of altruism described below. If she had not put the needs of others before her own, her music career may have turned out much differently. She intentionally deviated from her own career path for her late husband and continues to do so for her son Shooter Jennings, who, under her tutelage, has emerged as a star performer. Jessi explained, “I pursue what my heart is stirred to do, I have been on the bench so to speak, but I pick my moments. She added, I express what my heart feels, there is a dark side to life that has opened my heart to love more and be compassionate of others and their weaknesses” (J. Colter, personal communication, August 15, 2014). While the magnitude of Jessi’s influence on others is scientifically immeasurable, many of her self-views and her enacted behaviors originated through consideration of how her life intertwined with those around her. She often subjugated her own needs for what she believes was a greater purpose and continues the practice to this day.

More mundane, yet common, behavioral examples of expressing altruistic motives include buying unneeded Girl Scout cookies, pasting bumper stickers on vehicles broadcasting allegiance to certain candidates or social concerns, preparing “blessing bags” for the homeless, or volunteering our cherished discretionary time to selective charities: behaviors devoid of any expectation in return. While one could argue that helping behaviors are primarily motivated by the goal of boosting our mood or self-esteem or by other self-serving concerns, evidence supports an altruistic interpretation of the described behaviors. One justification for altruistic motives is the empathy arousal hypothesis (Batson, 2010a,b), which contends that individuals will assume the feelings of others and be personally motivated to action by restoring others to a state of physical or psychological comfort. Energized by the goal of reducing personal distress, an empathy arousal interpretation assumes that the helper makes an emotional connection with the distressed individual, provoking personal empathy, whereby the spontaneous needs of the empathetic person cannot be relieved until the assumed perils of the person in distress are overcome. This empathy motive likely explains the behavior of Jessi Colter.

Sometimes, the phenomena of reducing peril is described as orchestrating a state of negative relief, typically characterized by one of four psychological determinants used to connect with the distressed individual. Empathy can be realized by taking the self-perspective of the other person and imagining how he or she thinks, conceiving how the self would think under similar circumstances, feeling like the person in distress through emotional matching, or through empathetic concern where the helper envisions how the self would feel under similar circumstances. Each state of empathy assumes that an emotional or cognitive connection is made with the distressed individual and the perspective of that person can be assumed either psychologically or emotionally (Batson & Ahmad, 2009).

Empirical support for the negative state relief model exists but is often debated on the grounds that pure altruism is a philosophical possibility but a pragmatic illusion (de Waal, 2008). Supporters of empathetic altruism contend that empathy can be experimentally induced by exposing research participants to the distressed condition of another person, followed by the opportunity for the participant to mediate the distress (Piliavin & Charng, 1990). Contingent upon the type of help provided, and if the research participant voluntarily elects to continue to offer help given the opportunity to withdraw, the tenability of the ease of escape hypothesis can be tested (Batson, 2010a, p. 112). Many studies reveal that even when given the opportunity to quit without stigma or consequence during an experimental situation, altruistic-empathy motives support behavioral persistence (Batson, 2010a,b). Biopsychological evidence confirms that helping another person and relieving the pain of others when using an empathy motive have similar brain localization in the left anterior insula and complementary neurological responses to relieving our own pain (Fan, Duncan, de Greck, & Northoff, 2011). However, neurological evidence has not empirically confirmed whether empathetic altruism is initiated only when a dualistic threat to the self and others is perceived, or if the perception of stress in others alone is sufficient to motivate altruistic action and activate the insula.

Altruistic behavior should not be ontologically relegated to strictly crisis interventions or viewed only through a catastrophic lens. Peer kindness and benevolence can be exhibited in learning and performance contexts through volunteerism, where individuals devote their time and energy to meet interpersonal, group, or organizational goals. Volunteering is defined as a deliberate, intentional, and non-obligatory form of helping (Aydinli, Bender & Chasiotis, 2013). The precise motive for volunteering across cultures and contexts is unclear; however, typically one of three motives explains individual and organizational volunteerism: Individuals usually volunteer (1) out of empathetic concern for others; (2) under the pretense of reciprocal altruism, where they expect something in return; or (3) for strictly egoistic reasons, including materialistic gain (Omoto & Snyder, 1995). The most commonly observed organizational motive for volunteerism is to strategically promote a company ideology of social responsibility, enhancing a company’s image to employees, consumers, and the general community (Grant, 2012).

Pragmatically, understanding volunteerism motives is secondary to cultivating an organizational climate that is conducive to helping and cooperation. Many individuals perceive volunteerism as an effective way to develop marketable job skills, as many organizations consider individual volunteerism as a basis to evaluate prospective employees (Deloitte, 2013). The MD can initiate practical steps to cultivate a prosocial disposition among workers and students, promoting altruistic behaviors and volunteerism alike, by designing work and learning cultures where supporting others is a learned and valued personal attribute. Brief and Motowidlo (1986) outlined several steps leaders can take to cultivate organizational altruism. First, leaders should exhibit behavioral and emotional consistency across all individuals, integrate cooperation into project planning, and include sharing and helping as foundational components of performance or behavior assessment. In addition, the development of a prosocial work culture is accomplished by leaders exhibiting a concerted effort to validate the importance of individuality, concurrent with a focus that organizational growth is contingent upon individuals modeling prosocial behavior throughout all facets of an organization.

Finally, knowing how to induce cooperative and gratuitous behavior is critical but is only part of the solution. Frequently, when individuals are contemplating assistance to others, they undergo a cost–benefit analysis calculating the personal rewards of helping, as well as the psychological and physical drawbacks of offering help. If the emotional costs are deemed too high, such as when individuals feel overly threatened, insecure, or not personally accountable for offering help, they will be far less inclined to exhibit adaptive helping behavior (Dovidio, Piliavin, Gaertner, Schroeder, & Clark, 1991).

A robust field of research indicates when people are willing to offer help. First, people are much less compassionate and less inclined to offer assistance to others when part of a group in comparison with when alone (Cameron & Payne, 2011), unless the helping context offers cues that the individual has a social or legal responsibility to help, as exemplified by Samaritan laws in many countries (van Bommel, van Prooijen, Elffers, & Van Lange, 2012). Individuals help more when the psychological cost of helping is low, and the need of the person needing help is considered to be substantial. Altruistic motives are attenuated when we believe the person in distress could have preempted the problem through proactive and decisive action of his or her own, justifying lower empathy and discounting negative social evaluation from others (Batson, 2010a,b). Unfortunately, willingness to assist others is also a function of many superficial associations between the helper and the person needing help, such as the perceived degree of physical, intellectual, racial, and gender similarities (Mallozzi, Mcdermott, & Kayson, 1990), as well as perceptions of in-group membership (Stürmer, Snyder, & Omoto, 2005). Although many of the factors above are only indirectly related to performance motivation, the helping contingencies described suggest that many altruistic behaviors are motivated by self-interest, how we see ourselves in relation to others, or an external standard of personal accountability.

The preceding narrative primarily focused on people taking specific actions to either deliberately, or unintentionally, boost their self-evaluations and subsequent self-worth. However, not all individuals are primed for action and willing to take specific steps to invigorate self-worth perceptions. Instead, many times individuals will appear apathetic and aloof, intentionally electing inaction. By using a series of complex, self-protection strategies, the individual can insulate the self and avoid the demoralizing prospect that others may think the individual has insufficient resources to meet learning and performance goals. We next examine which strategies learners employ to maintain elevated competency beliefs, motivated by the strong desire to protect the individual from harmful self-intrusions and public repudiation.

Principle #43—Performance inhibiting strategies augment self-worth

Some individuals, especially adolescent students (Alderman, 2004), are highly motivated by the goal of worthiness. Superficially, these individuals portray a confident façade when staring into the metaphoric mirror; they want to be perceived as Herculean in the eyes of their beholders. Looking good requires positive self-affirmations coupled with encouraging feedback from others, asserting that the individual is competent and capable: someone who is able to overcome academic hurdles and master challenging performance goals. But sometimes, during the iterative process of self-evaluation, even the most confident individuals become highly self-critical, questioning the legitimacy of their knowledge and ability. The emotional conflict of self-doubt and uncertainty may lead to psychological ruminations concerning the precise caliber of their competency perceptions. In extreme cases, and despite actual ability, these individuals may come to believe they do not have the necessary talent or requisite skills to be academically, socially, or vocationally adept, leading to feelings of unworthiness (Covington, 2009). In order to quell anxiety and sustain a positive self-image, individuals will frequently use self-protective strategies to preserve their positive affirmations: concealing or forestalling any aspersions of performance inadequacy or academic impotence. Although these strategies are self-protective of ability attributions, the approaches are frequently counterproductive, resulting in performance deficits on tasks and are thus categorized as self-handicapping strategies (SHS).

Deliberate handicapping is an active process designed “to diminish the threat of failure by obscuring low ability as the reason for the failure” (Brown & Kimble, 2009, p. 609). SHS serve three main purposes for the individual. First, the strategies allow the person to justify undesirable performances and “save face” by shifting responsibility for any negatives outcomes from the internal self to external causes (Schlenker, 1980; Warner & Moore, 2004). Second, SHS insulate the individual from their own negative self-perceptions, enhancing self-esteem, and thus sustaining or increasing individual self-worth (Berglas & Jones, 1978; De Castella, Byrne, & Covington, 2013). Third, the use of SHS sometimes results in self-enhancement, when positive task outcomes are achieved despite the use of the failure-avoiding, performance-damaging strategies (Tice, 1993).

The variability of SHS is broad, primarily determined by the context of application. Most SHS research focuses on academic performance, when strategies thwart attributions of low ability and protect academic self-esteem (Schwinger, Wirthwein, Lemmer, & Steinmayr, 2014). To a lesser extent, researchers investigate the impact of SHS on organizational behavior, where strategies are designed to protect organizational image and enhance business integrity, such as when a company rationalizes an environmentally unsound decision as necessary to help improve people’s lives (Higgins & Snyder, 1989). Self-handicapping also has significant interpersonal implications. Individuals use SHS when subjected to episodes of social exclusion, most notably from soured relationships or in response to devastating personal milestones, such as bereavement for a close friend or spouse. Frequently, these personal events trigger a variety of self-defeating behaviors, including excessive food consumption, drunkenness, or drug use. Although SHS are self-deprecating, the strategies provide the individual with an outlet for situational relief, leading to a state of limited self-awareness, temporarily insulating the person from the reality of his or her loss (Twenge, 2007).

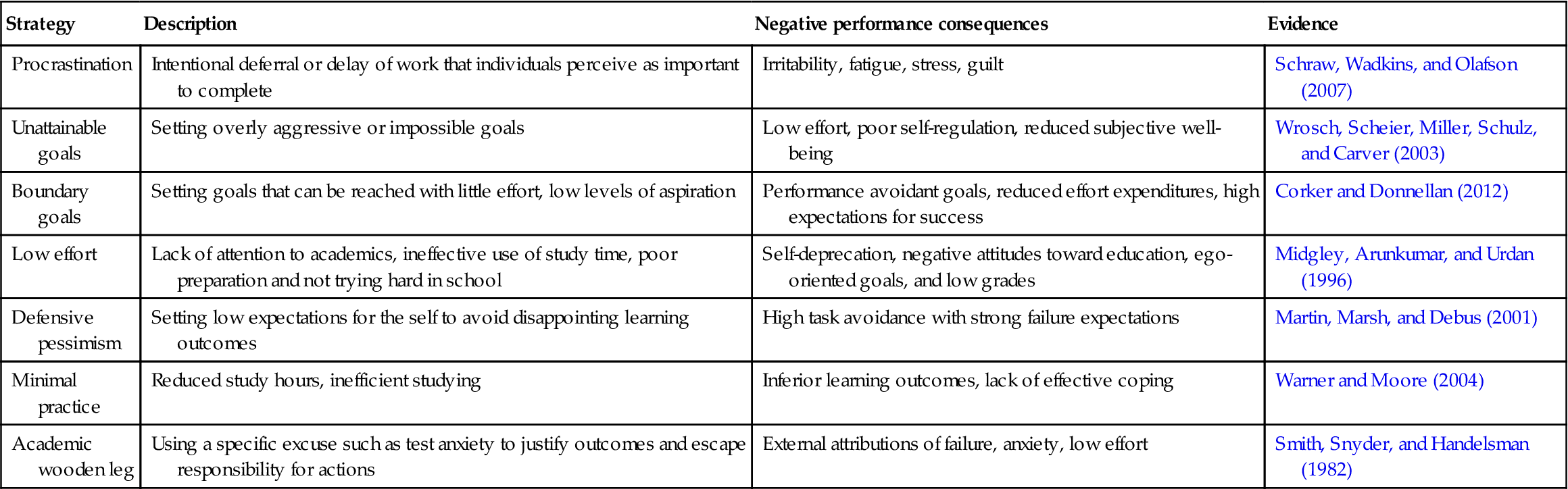

In regard to learning and performance, the primary benefit of using SHS is to promote positive perceptions of the self by others and obscure any connection between negative results and personal lack of ability. The most common contingencies resulting from the use of SHS are the perception that external reasons justify episodes of inferior performance, shifting blame away from the individual and artificially insulating the self from intrusive and disturbing self-perceptions, which are equated with decreases in self-worth. The motivation to avoid failure prompts the use of techniques, such as procrastination, setting unattainable goals, or deliberately withholding task effort. Although these strategies may appear to accelerate failure, in the mind of the actor they serve a self-protection motive, designed to increase, not decrease self-worth. By using SHS the individual has a viable rationalization, or a seemingly justified excuse, in the event that performance suffers. Individuals can attribute any negative outcome to the use of the strategies, not to the self, and effectively avoid the psychologically decimating prospect that they actually have low ability. In the eyes of the individual, it is considerably easier and much more palatable to acknowledge that you could have done better if you had tried harder or had not waited until the last minute than to admit to yourself and others that you might have limited ability. Table 8.2 lists some of the more common academic SHS, along with the potential negative performance consequences associated with each type of strategy use.

Table 8.2

The potential liabilities of academic self-handicapping

| Strategy | Description | Negative performance consequences | Evidence |

| Procrastination | Intentional deferral or delay of work that individuals perceive as important to complete | Irritability, fatigue, stress, guilt | Schraw, Wadkins, and Olafson (2007) |

| Unattainable goals | Setting overly aggressive or impossible goals | Low effort, poor self-regulation, reduced subjective well-being | Wrosch, Scheier, Miller, Schulz, and Carver (2003) |

| Boundary goals | Setting goals that can be reached with little effort, low levels of aspiration | Performance avoidant goals, reduced effort expenditures, high expectations for success | Corker and Donnellan (2012) |

| Low effort | Lack of attention to academics, ineffective use of study time, poor preparation and not trying hard in school | Self-deprecation, negative attitudes toward education, ego-oriented goals, and low grades | Midgley, Arunkumar, and Urdan (1996) |

| Defensive pessimism | Setting low expectations for the self to avoid disappointing learning outcomes | High task avoidance with strong failure expectations | Martin, Marsh, and Debus (2001) |

| Minimal practice | Reduced study hours, inefficient studying | Inferior learning outcomes, lack of effective coping | Warner and Moore (2004) |

| Academic wooden leg | Using a specific excuse such as test anxiety to justify outcomes and escape responsibility for actions | External attributions of failure, anxiety, low effort | Smith, Snyder, and Handelsman (1982) |

Although the examples provided in Table 8.2 suggest that most instances of SHS are barriers to successful performance, at times, SHS can be adaptive and situationally support academic prosperity. In instances when an individual uses SHS and unexpectedly observes positive consequences despite the strategy use, increases in academic self-esteem typically follow (Tice, 1993). For instance, when a procrastinating student deliberately delays a semester-long project by waiting until the last minute to start work, academic efficiency is realized because the student is able to complete more work in less time than when the project is started several weeks in advance of the deadline (Schraw et al. 2007). Setting lofty goals may also have positive implications. Individuals who set unattainable goals, upon realization of the low probability of reaching their goals, disengage from the lofty goals, then re-engage, by setting more practical expectations for themselves. Goal recalibration results in stress reductions, fewer reported depression symptoms, and overall higher optimism concerning life experiences (Wrosch et al., 2003).

Organizationally, social loafing, which occurs when individuals exhibit lower effort when working in groups than when working independently, can be motivationally adaptive (Shepperd, 1993). During group work, individuals doubting their own abilities often deliberately withhold effort as a self-protective strategy, preferring criticism of their low effort to negative evaluations of their work performance. Known as the free-rider effect, individuals may potentially enhance their academic self-esteem through group affiliation, if positive group results are achieved, leading to positive team praise or materialistic group benefits for the individual despite questionable individual contribution. Unfortunately, self-protection motives and associated SHS more frequently result in performance decrements, as evidenced by Table 8.2, because strategies are often counterproductive to meeting learning objectives. In a recent meta-analysis, Schwinger et al. (2014) observed a mean negative correlation between academic performance and use of self-handicapping of−.23, indicating that as the frequency of SHS increases, academic performance declines.

While performance reductions and inferior results are easily measured, mediation of behavioral self-handicapping is not. Schwinger et al. (2014) lamented that empirically supported interventions that address SHS are “barely available” (p. 14). Complicating implementation of remedies is the recurring obstacle that many individuals may not realize or understand the rationale for their own actions (see Principle #5, p. 12). Perception and use of SHS may be implicit, below the direct consciousness of the individual. Thus, the MD is faced with a formidable triple-threat challenge. First, the individual must acknowledge the futility of the failure-avoidance motive and the potentially disruptive consequences of using SHS. Second, upon realization of strategy implications, the individual must recognize when SHS are used. Finally, maladaptive SHS must be replaced with adaptive strategies, which concurrently address performance challenges while instilling self-esteem and supporting enhancement of overall self-worth.

The few interventions found to reduce SHS focus on cognitive restructuring, including instilling in learners a greater emphasis on the value of education and why using self-regulation strategies, such as monitoring and planning, typically result in learners adopting mastery-approach goal orientations (Martin, 2005). However, considering that the primary motive for using SHS is to avoid failure and sustain self-worth, it is essential that habitual SHS users realize that expertise is effortful and deliberate and that failure is a malleable part of the learning and performance process, not an immutable, personal flaw. As Nick Lowery reminded us in Chapter 7, we must always give ourselves permission to learn. The origination of SHS is largely a function of psychological frailty, partly fueled by a strong emphasis on individualism. In order to jettison nonproductive SHS, learners and workers alike must believe that the “real me” can be respected and valued at all times, even when results occasionally fall short of expectations. Leadership actions and organizational programs that focus on incremental skills development, debunking the misconception of rigid ability, will shift the individual from a fixation on the self and, instead, impart a focus on what can be attained with effort, deliberation, and dedicated practice.

Chapter summary/conclusions

Individuals may not realize or understand the rationale for their own actions. The implicit nature of many motivational beliefs obscures the individual from making accurate and definitive assessments of the self or clearly understanding who is “the real me.” Lacking criterion evidence, individuals often resort to social comparisons by paralleling themselves to meaningful others or to normative standards. Once personal benchmarks are defined, individuals conduct introspective self-evaluations, assessing consistency between their enacted and desired selves. Positive judgments produce satisfaction, elevated self-esteem, and escalating self-worth, while negative discrepancies promote disenchantment and angst, as individuals struggle to understand their relational value and assess their comparative self-worth.

The presence of others is a powerful motive that induces individuals to display different behaviors in public than in private, based upon who is watching, the intensity of personal beliefs, normative expectations, and the type of impressions we wish to make. Social influence determines if we conform or disobey, participate or withdraw, reciprocate or oblige, and when and why we are willing to exhibit prosocial behaviors to serve and cooperate with others. Sometimes, we help to satisfy our own egoistic needs, motivated by the quest to create positive impressions and develop self-worth. Other times, we volunteer in the name of altruism, motivated by empathetic concern and a genuine unsolicited desire to satisfy the needs of others before we satisfy our own. Competency perceptions trump all self-beliefs, and perhaps are the strongest motive of all. Individuals will employee radical SHS, such as procrastination and setting impossible goals as a subterfuge to sustain positive self-worth, having others believe that our personal misfortunes are inevitable consequences of our efforts, but only circumstantial evidence, unrelated to who we are or what we might want to be.

Next steps

Assessing personal and normative fit requires that we consider mountains of belief, contextual, and behavioral evidence. The evaluative decisions help determine perceptions of our identity and self-worth, which, in turn, trigger a corresponding series of feelings, often interpreted as emotions. Success may breed pride, joy, and optimism. Failure may portend anger, humiliation, guilt, and depression. Every emotion is a powerful, subjective reaction to what we experience that frequently determines how we think and feel but, more importantly, what we do next. Chapter 9 examines the world of moods, dispositions, and emotions, revealing how our feelings radically alter the tasks we consider and what we are willing and able to accomplish. Alec Torelli returns in Chapter 9, as we learn that one key to optimal performance is an exceptional ability to regulate emotions, even when things do not turn out as planned.

End of chapter motivational minute

Principles covered in this chapter:

36. The psychological or physical presence of others may alter normative behavior—people are influenced by others and act differently in public versus in private. Typically, normative behavior is demonstrated to satisfy motives of social acceptance and group inclusion.

37. Prosocial behaviors are compliant, adaptive, and predictable—individuals are willing to help others for reasons of personal satisfaction; because of the perceived needs of fairness, reciprocity, and consistency; or out of obedience in respect of power.

38. Prosocial motives are egoistic and altruistic—some individuals offer to help to others for egoistic reasons that are motivated by a desire to satisfy one’s personal psychological needs. Altruistic helping is motivated by the genuine desire to assist others based upon empathetic thoughts and feelings about the person in need.

39. Performance inhibiting strategies augment self-worth—protecting the self is a decisive motive based upon the prospect of looking good and avoiding failure. Self-worth can be protected by the use of SHS that shift blame for failure to external factors unrelated to ability perceptions.

Key terminology (in order of chapter presentation):

Subjects—research participants in a research study that do not have explicit awareness of the purpose of the research.

Subjects—research participants in a research study that do not have explicit awareness of the purpose of the research.

Confederates—individuals who participate in a research study and are aware of the purpose of the study and primarily participate to induce behavioral changes in actual study subjects.

Confederates—individuals who participate in a research study and are aware of the purpose of the study and primarily participate to induce behavioral changes in actual study subjects.

Bystander effect—the phenomenon whereby the public helping behavior of an individual is influenced by the presence of others.

Bystander effect—the phenomenon whereby the public helping behavior of an individual is influenced by the presence of others.

Impression management—the process used by individuals to generate and control desired opinions in others.

Impression management—the process used by individuals to generate and control desired opinions in others.

Prosocial behavior—gratuitous and cooperative behaviors usually initiated to help and assist other individuals or groups in meeting desired goals.

Prosocial behavior—gratuitous and cooperative behaviors usually initiated to help and assist other individuals or groups in meeting desired goals.

Egoism—the demonstration of cooperative and helping behaviors primarily motivated by the desire to enhance one’s own psychological, materialistic, or social needs.

Egoism—the demonstration of cooperative and helping behaviors primarily motivated by the desire to enhance one’s own psychological, materialistic, or social needs.

Reciprocity—the prevailing belief in many cultures that obligates individuals to return help when others have helped the individual.

Reciprocity—the prevailing belief in many cultures that obligates individuals to return help when others have helped the individual.

Spillover effect—the obligatory tendency to offer help to friends of friends.

Spillover effect—the obligatory tendency to offer help to friends of friends.

Altruism—the demonstration of cooperative and helping behaviors primarily motivated by a desire to help meet the needs of others.

Altruism—the demonstration of cooperative and helping behaviors primarily motivated by a desire to help meet the needs of others.

Self-handicapping strategies—idiosyncratic performance damaging approaches used by individuals to diminish or conceal self-perceptions of failure believed to be caused by low ability.

Self-handicapping strategies—idiosyncratic performance damaging approaches used by individuals to diminish or conceal self-perceptions of failure believed to be caused by low ability.

Social loafing—the phenomenon of individuals exhibiting lower effort when working in groups than when working independently.

Social loafing—the phenomenon of individuals exhibiting lower effort when working in groups than when working independently.

Social identity—the process of establishing and communicating one’s beliefs, individuality, and self-concept to another person based upon social interaction.

Social identity—the process of establishing and communicating one’s beliefs, individuality, and self-concept to another person based upon social interaction.