THOUGHTS OF HOME TEMPTED WASHINGTON LONG BEFORE he left the frontier. Warfare, he knew, threatened rather than promoted his fortune. In April 1757, while still serving on the frontier at Fort Loudon following a brief visit to Alexandria, Washington had griped to his distant cousin Richard Washington, a London merchant: “I have been posted then for twenty Months past upon our cold and Barren Frontiers, to perform I think I must say impossibilitys. . . . [B]y this means I am become in a manner an exile.” Hopefully anticipating his return, George asked his cousin to order on his behalf an extensive shipment of items for the renovation of Mount Vernon, such as a chimney piece, 250 window panes, wallpaper, tables, chairs, and door locks. No doubt with a grunt of irritation, he then rode off to confront the French and Native Americans with all their “hellish Arts.” George’s ill-tempered bickering with Forbes over the wilderness road partly reflected his frustration with military affairs and his yearning to settle down to domestic business.1

Washington took another leave of absence from the frontier in March 1758 and rode, sick and grumpy, to Williamsburg to consult with a physician about his lingering dysentery. The doctor found nothing seriously amiss, and it was a more hopeful Washington who attended dinner that evening and heard that the colony’s wealthiest widow resided nearby. Her name was Martha Dandridge Custis, and her husband, Daniel, had died the previous July. She was exceptionally rich and had already attracted other potential suitors. Charles Carter, more than twenty years older than Washington but unlike him a planter of the first rank and a prominent politician, called her “the object of my wish.” Perhaps concerned that he had no time to lose before the prospect vanished, Washington resolved to visit her immediately. On March 16, the morning after his visit to the doctor, he hopped into the saddle and rode straight for the widow Custis’s plantation at White House on the Pamunkey River in New Kent County.2

The first meeting was a great success from both points of view. Washington, well-dressed and amply tipping the servants, cut a good figure. For this he could thank Sally Fairfax—with whom he was still infatuated—and the society at Belvoir, where he had learned gracious manners. Martha and George spent the afternoon and evening together—probably in the company of others—and he may have spent the night. The next day Washington returned to Williamsburg, where he ordered elegant new tack for his horse, including a “Sumpture Saddle” and silver-embroidered holster caps.3

On March 25, encouraged by Martha, he reappeared at White House for a brief layover before galloping off to the frontier. Some time that day or perhaps during a return visit in early June they probably exchanged promises, for not long afterward Washington initiated plans to expand Mount Vernon’s mansion house—an unlikely investment unless he both had extensive financial prospects and intended to settle down in the near future. He and Martha separately and simultaneously ordered fine new sets of clothing.

Marriage with Martha offered George a shortcut to fortune. Her wealth had primarily originated with her late husband. The story of the Custis estate was well known in Virginia, and must have inspired Washington. Martha’s father-in-law John Custis began with an inheritance of 5,000 acres on the Eastern Shore. He doubled that when he married the equally well-endowed Frances Parke, acquiring land along the York River. Though an ill-tempered and sometimes brutal man, John Custis was a talented entrepreneur and a believer in scientific agriculture. He ran his estates efficiently, earning ample profits on their produce. He also scrupulously avoided borrowing, leaving his son Daniel Parke Custis an extensive string of plantations along with ready, liquid assets.

Daniel, who married Martha in 1749, emulated his father in managing his wealth. He died suddenly and intestate in 1757 but left a massive inheritance to his wife and two children, Jacky and Patsy. Together they could claim title to almost 18,000 acres, including newly acquired land in King William County. This acreage, along with slaves, improvements, and personal property, was valued at £30,000. But that was not all. Additional assets that he had squirreled away in the colonies and England amounted to another £10,000. Since Daniel’s death Martha had been managing this vast estate on her own—efficiently on the whole, but with a weakness for lending money to friends and relatives.

Some said that Martha and George married for love; others, that he just desired her money. For Martha, who turned down the financially more eligible (and obviously besmitten) Charles Carter in favor of George Washington, personal preference, even love, must have held some sway. George may not have known his own feelings. Martha was certainly a worthy match. Though not well-educated, she was intelligent, personally amiable, young, and physically attractive. But she was also very wealthy. And while most of her estate would go to her children if they survived—although it would take years to settle Daniel Custis’s complex legacy—George would be responsible for managing the entire estate. Merged with his considerable holdings, it would become quite a substantial enterprise. In an instant he would become one of the most financially powerful men in Virginia. If he had children, they could expect to follow in his stead.

George was in a frivolous mood the night before his wedding, relaxing with friends at a tavern and losing magnificently at cards. He could afford the hit to his pocketbook. On January 6, he and Martha exchanged vows at the White House plantation. They spent the next few weeks there, enjoying a bitterly cold but gloriously snow-draped Virginia landscape. The couple then moved to Williamsburg, where George took his seat in the House of Burgesses on his twenty-seventh birthday. Martha meanwhile pondered what she should bring to Mount Vernon.

George, not yet having made the full conversion from bachelordom, still absconded occasionally to local taverns to drink and play cards. But he also took Martha to balls, bought and sold horses, began drawing cash from the Custis estate, and crafted ambitious plans for expansion. George and Martha intended to arrive at Mount Vernon in early April, and he wrote ahead to his overseer to have the mansion house “very well cleaned” and aired.4

On their journey the young couple may have toured some of the Custis lands and taken in the old neighborhood at Fredericksburg and Ferry Farm. Then, pushing northeast, they crossed the Occoquan to enter a region defined by three great estates—Gunston Hall, Belvoir, and Mount Vernon—and one town, Alexandria. Almost twenty miles separated the first from the last, encompassing an interdependent community of towns, villages, and estates.

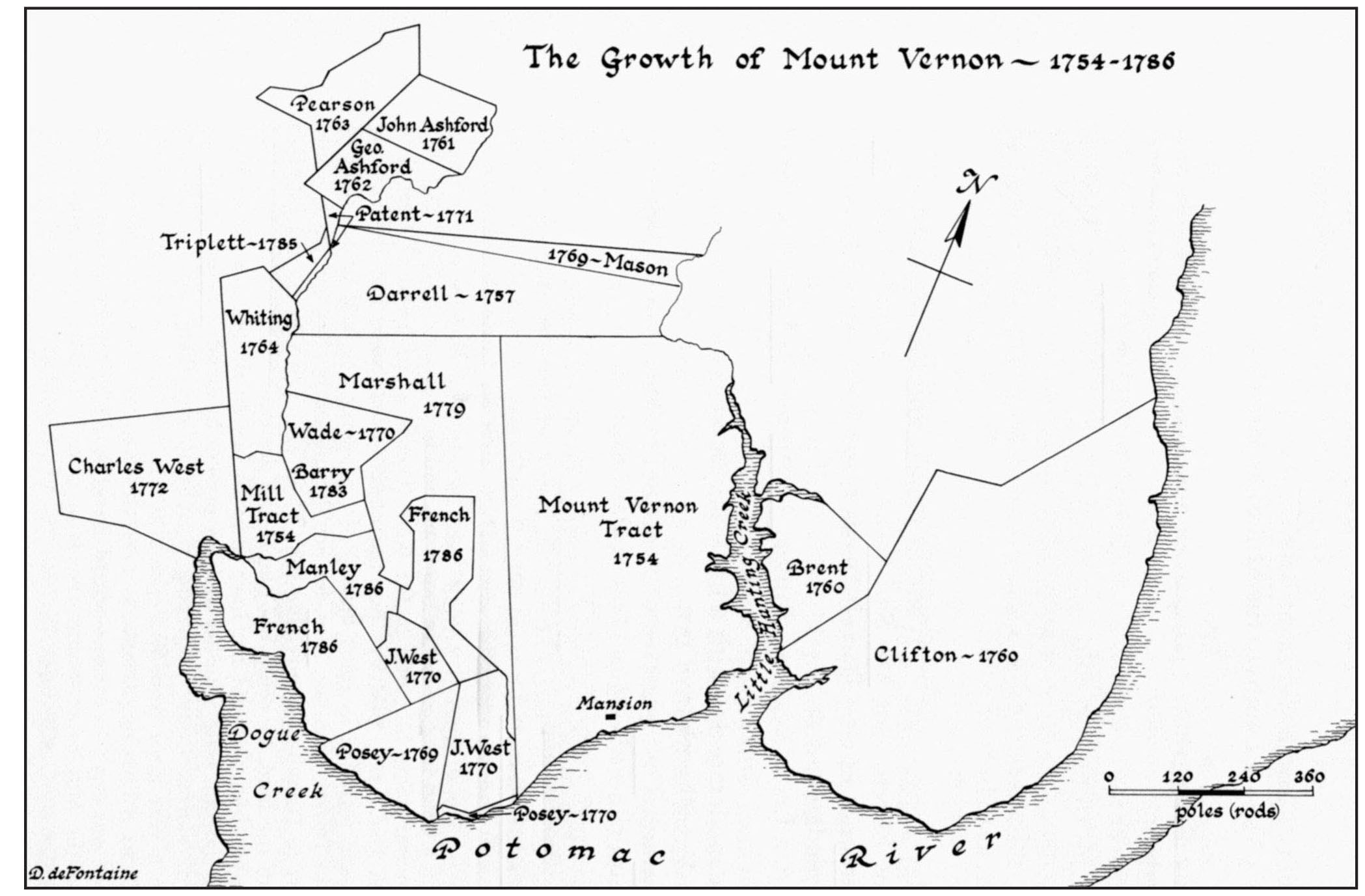

Leaving Belvoir, the Washingtons crossed Dogue Run to enter their home neighborhood. After passing through the isolated, 172-acre Mill Tract, they traversed a number of privately owned smallholdings—on which George may have cast a covetous eye—before entering the central estate. Approaching it amidst the splendor of springtime as they did in 1759, George and Martha could gaze with the satisfied benevolence of proprietors over the center and foundation of their new domestic empire.

Vertically rectangular, bounded by the Potomac on the south and Little Hunting Creek on the east, the original Mount Vernon estate had comprised some 2,126 acres. To this George added a 500-acre tract at its northern tip in 1757. Much of the land was still forested, but the fields seemed good and fertile, and the ground was level and just fifty to a hundred feet above sea level. Only later did Washington understand the limitations that the red clay beneath the topsoil placed on the estate’s fertility.

Nothing otherwise distinguished the place except the site of its mansion. Riding toward it past fields in which slaves, white workers, and their overseers were busy with spring planting—mostly tobacco—he must have marveled again at its magnificent situation on a bluff overlooking the Potomac. From there, whether in his study or on the piazza he eventually built, his mind could encompass the interconnectedness of the surrounding large and small estates on both sides of the river.

The mansion house was impressive by the standards of the time. Lawrence had substantially expanded the original humble structure, so that by 1759 it stood one and a half stories tall with four ground-floor rooms and four smaller chambers above them. George intended to embellish the mansion further, and it needed extensive repairs. First, though, there was the land to tend to.

Washington’s first months at Mount Vernon with Martha established habits that would last a lifetime. Just after rising, and before breakfast, he would dress himself and dispatch servants to prepare his gear (including, if necessary, surveying equipment) and saddle his horse. Then he would ride out to get a feel for his estate. Those first rides must have been exhilarating. Warmed by spring sunshine or soaked by rain—for he was not the type to shelter from inclement weather—he took the circuit of his estate, examining boundaries; inspecting timber and soil quality; praising or reproving slaves, workers, and overseers; and looking over the existing crops. From the mansion house, a typical day’s circuit could have taken him ten miles. Only after it was done would he return home to eat.

These journeys certainly included the exploration and careful delineation of the local waterways. Several years earlier, he had stood at the falls of the Ohio and marveled at not just their beauty but their commercial potential. Now he traced the Potomac and its numerous tributaries, conscious that they formed the arteries and veins carrying his estate’s lifeblood. All he had to do was step out onto his piazza to enjoy a view—perhaps the grandest anywhere—of the Potomac.

Or he could simply ride along the shore. The portion he initially owned was small, but in 1760 he would purchase 2,000 acres of good river land on the other side of Little Hunting Creek, and in subsequent years his acquisitions would expand his estate west along the shoreline to Dogue Run. On any given day the riverbank would have been dotted with slaves and servants fishing for the master’s table. Washington also frequently availed himself of the numerous river ferries to visit friends and business associates in Maryland.

The Mount Vernon estate was much more than a mansion house surrounded by land. It lived and breathed as an active community. At its center stood Washington and his family, who both directed and depended upon the people around them. These included temporary workers of all sorts hired on contract, overseers, and visitors such as couriers and deliverymen. But the largest single group of people inhabiting his estate consisted of enslaved African Americans. From a few dozen whom Washington owned at Mount Vernon in 1759—in addition to Martha’s dower slaves, who mostly worked the Custis estates—this population eventually grew by purchase and procreation into the hundreds.

Like his peers, Washington primarily viewed slaves as commodities. At the same time, however, he regarded them as personnel to be managed. Though slaves, they were still people, and so needed motivation to be productive. As a slaveholder Washington tried to be reasonable but firm, demanding hard work and obedience but without the excesses of cruelty that characterized many other estates. Moderation was for him at this time less a moral than a business principle. Put simply, he thought the slaves would work harder if he treated them well—such as providing decent food, shelter, and medical care—than they would if he managed them cruelly. Savage discipline was from his perspective both wrong and counterproductive. Recognition of the moral injustice of slavery, and of the perverse logic of attempting to motivate people who were denied their freedom, would come to Washington only slowly.

Mount Vernon’s population, free and enslaved, formed part of an extended social and political network of multiple estates, smallholdings, farms, and towns. Washington often rode southwest from his estate to sumptuous Belvoir, filled with friends and youthful associations. Continuing south along the Potomac, a short ride took him to Gunston Hall, George Mason’s newly built Georgian masterpiece that was beautifully situated overlooking a bay formed by the mouths of the Pohick and Accotink Creeks. Social and business associations with the Fairfax and Mason families meant short day trips or, more often, the dispatch of a messenger with a brief letter, receipt, or account. On any given day the roads between these estates would have bustled with horses, carts, and people carrying all manner of mutually enriching goods and communications.

While exploring this network’s potential, George wrestled with the Custis estate’s legal settlement. He was determined that not one shilling of it would escape him or his family. He peppered Stafford County lawyer John Mercer with incisive questions on his and Martha’s legal rights respecting the estate. Taking thorough inventories of the Custis property, Washington noted slaves (with names, locations, relationships, and valuations), livestock, tools, furniture, clothing, and china—even pots of raisins. With all the meticulous care with which he had composed surveys in his youth, he detailed, classified, and valued every item. In a separate account, he listed the goods that Martha had taken from the Custis estate for her own use, including even “a little Brandy & some old Cyder” that he valued at £1. He also prepared a full catalog of Daniel Parke Custis’s extensive library. There were good legal reasons for copying or composing these inventories—George was no miser counting his pennies—but the work must have taken many days and nights in which he came late to bed or not at all.5

For the first few months after his marriage, Washington still gambled (and lost up to £5 at a time) at horse racing, billiards, and cards, and the inevitable first postmatrimonial quarrel may have occurred at about this time. His accounts reveal that shortly afterward his expenditures on cards ceased entirely, and that he played at billiards only occasionally (and perhaps surreptitiously). Martha might well have peremptorily ordered him to stop gambling, only to relent a few years later when George’s expenditures on cards resumed at a low level while billiards ceased—perhaps as a quid pro quo.

George was no gambling addict, however, and his idle pursuits never diverted him from business. In his household economy he emulated the woman he affected to resent—his mother. Like her, he emphasized practical efficiency and thrift. Mount Vernon was a gentleman’s seat, not a miser’s abode, and so there were frequent visitors and parties. But there also were standards to maintain. Washington adhered to these more strictly than anyone else in his family. The gentry had its share of dissolute scoundrels who shamed their families and ruined their estates. He was determined not to be one of them. Mount Vernon had to be a beacon of prosperity, not a bitter example of neglect. Martha felt the same, and proved an energetic and effective household manager.

Leaving Mount Vernon’s domestic machine humming smoothly under his wife’s oversight, George often took the easy eight-mile ride to Alexandria. In 1759 the town was hardly a metropolis, but it was young and had a bright future. The town’s political importance had been established just five years earlier with the opening of the Fairfax County Courthouse. Now it was becoming not just an administrative but a commercial center. Alexandria was perfectly situated for navigation, as described by a gentleman who visited it shortly after George and Martha married. “The Potomac above and below the town is not more than a mile broad,” he wrote, “but it here opens into a large circular bay of at least twice that diameter. The town is built upon an arc of this bay, at one extremity of which is a wharf; at the other a dock for building ships; with water sufficient to launch a vessel of any rate or magnitude.” Trustees oversaw Alexandria’s development with a view toward making it a major commercial center for the enrichment of all the communities, including Mount Vernon, along the Potomac.6

Ships docked at the Alexandria wharf and unloaded boxes addressed to “Mount Vernon Potomack River Virginia”—the former being, as Washington explained to a merchant, “the name of my Seat the other the River on which ’tis Situated.” Goods-laden wagons escorted by servants and slaves trundled from Alexandria to Mount Vernon and returned with hogsheads of tobacco from the Custis and Washington estates. At Alexandria, workers unloaded the tobacco and stacked it in warehouses, where it awaited inspectors bearing stamps of rejection or approval. Heaved on board transatlantic vessels, this tobacco was destined for London, where it was transformed into cigars and snuff for the enjoyment of British lords and ladies—maybe even the king himself. Much of it eventually was sold in the markets of continental Europe.7

Washington visited Alexandria to oversee the exchange of goods in both directions, and stood at the wharf to watch the work under way and worry about the handling of his tobacco. Mostly, however, he managed this ongoing business from his desk at Mount Vernon. He had been corresponding with British merchants since his earliest days as an estate proprietor. After his marriage, Washington entered into a relationship with the prominent firm of Robert Cary & Company, which had worked with the Custis family for many years. This relationship merged his own inheritance—enhanced by personal acquisitions, the fruit of his labor as a teenage surveyor, thrifty money management, and investment—with the Custis estate that had fallen to his stewardship by marriage. Quite apart from his love for Martha, as a conscientiously responsible man George felt compelled to properly manage and enhance his wife’s and stepchildren’s inheritance even as he leveraged it to build his own fortune.

On May 1, 1759, George addressed Cary & Company—enclosing a certified copy of his marriage certificate—as the new manager of all commercial affairs relating to the Custis and Washington estates. In transactions that both sides carefully documented, Washington shipped tobacco to the care of Cary & Company, which sold it on consignment in Europe and credited the proceeds to his account. Meanwhile, he ordered from the firm all of the European manufactured goods that he needed for the improvement of his estate and his own enjoyment. George developed ongoing relationships with other English merchants as well, such as John Hanbury & Company of London and James Gildart of Liverpool.

Imported British goods were vital to the improvement and expansion of the Mount Vernon mansion house, a project dear to Washington’s heart. His younger brother Jack, who had managed it in George’s absence, was well meaning but not up to the job. After returning from the war, George was shocked at the “rundown” appearance of the place. Outbuildings were crumbling, the lawn sprouted patchy and rank with crabgrass, and the main mansion looked barely habitable.

George and Martha prioritized redesigning the bedchamber according to her wishes, with blue and white themes for the new tester bed with canopy and curtains, chairs, draperies, and other furnishings. The young couple ordered a “Fashionable Sett of Desert Glasses, and Stands for Sweet Meats Jellys &ca together with Wash Glasses and a proper stand for these,” along with cutlery, carpets, fire screens, and other items—enough to put on a decent show of gentility until the house could be expanded.8

In the same letter to Cary in which he requested new furnishings for the mansion house, George asked for “the newest, and most approved Treatise of Agriculture . . . called a new System of Agriculture, or a Speedy way to grow Rich.” The title was revealing. For Washington and his fellow planters engaged in the competitive world of Virginia farming, it was no prosaic rural pastime. Farming was a business, a venue for entrepreneurs to show their worth and talent for innovation. Acquiring wealth was the goal, and the devil took the hindmost.9

Just as Washington loved being fashionable and up to date in all his occupations, including his dress, he knew that falling even a little bit behind in business could pave the way to ruin. Throughout his life, he sought the latest books on agriculture and husbandry, and corresponded with the leading agriculturalists of his day. It was in this spirit that Washington ordered “the latest Edition” of William Gibson’s manual on the treatment of horses; Batty Langley’s New Principles of Gardening; and “One neat Pocket Book, capable of receiving Memorandoms & small Cash Accounts.”10

Washington still had much to learn about entrepreneurship. Among other things, he had yet to diversify his investments. Visitors to his estate would have been immediately impressed by the green fields of tobacco and the barns in which cut leaves were hung to dry. This crop had been the staple source of profit for Washington and other planters for many generations. Growing and preparing the finest possible tobacco was a source not just of potential profit but of social standing in colonial Virginia. He did not initially consider chancing a switch to some other crop.

Many farmers preferred to play it safe with tobacco, selling it to Virginia merchants for a modest but steady return. But Washington was eager to extend his profits, and so gambled on the riskier but potentially much more lucrative trans-Atlantic trade. The danger of lost cargo was real, thanks to French naval activity—the war did not end until 1763—and the frequent storms during the fall and spring shipping seasons. Costs for insurance and freight were likewise high, and British import duties were even more onerous. Then there were handling duties, and the cuts taken by the merchants managing the business. Still, the earnings could be good if market prices held, although British regulations prevented planters from selling to non-British buyers.

There was another temptation to sticking with tobacco: easy credit. Currency of any sort, but especially hard currency, was exceptionally difficult to find in colonial Virginia. Credit, however, was plentiful for interested planters thanks to British tobacco merchants. The credit they offered provided the needed capital for the purchase of land, slaves, and the British manufactured goods necessary for production and maintaining the Virginia gentry’s opulent lifestyle. Credit was financed with tobacco. In the short run, easy credit seemed to offer the means for enrichment via the ever-expanding production of tobacco. But it reinforced colonial dependency on the mother country, and it depended in turn on the continuing profitability of tobacco in British and European markets. If tobacco prices plummeted or even fluctuated, planters faced ruinous debt and bankruptcy. The risk was theirs alone.

Washington stuck with tobacco despite some troubling signs in the air. The Virginia tobacco crop’s yield for 1758 was low, but scarcity gave no substantial boost to prices in London markets. Despite this stagnancy, he remained cautiously optimistic that tobacco would soon return to profitability. The crop of 1759 promised a “favourable aspect at present,” Washington told the London merchant John Hanbury, and “self Interest” would predispose him in favor of whatever merchant demonstrated the “greatest Exertion in the Sales” of his tobacco.

Not all tobacco was created equal, of course. Leaf grown on the Custis estates along the York River, Washington learned, was particularly sweet smelling and sold more rapidly and for higher prices than other tobacco. He therefore considered planting York River tobacco seed at Mount Vernon and on his “fine Lands” in the Shenandoah, provided that the crops would be “managed in every respect in the same manner.”11

The system seemed simple—for a time. Washington could maintain the tried-and-true tobacco system—being sure to keep up with the latest practices—and reinvest a portion of his profits in more land, better equipment, more paying tenant farmers, more livestock, and ultimately more tobacco. At the same time he could purchase shiploads of fine cloth, elegant saddlery, expensive home furnishings, and dainties such as mangos, “best Porter,” “perfumed Powder,” and packs of playing cards.12

Washington’s taste for such items reflected a growing American fascination with consumer goods. His interests were both personal and symbolic. He ordered a collection of busts of military heroes as well as statues of two “Furious Wild Beasts” (though because the military busts were unavailable he had to settle for busts of more peaceable luminaries alongside “Two Lyons after the antique Lyon’s in Italy”). As the busts emphasized, Washington was a retired military hero, a lion of the battlefield now taking his place as a civil leader. He even spoke of sating his “longing desire” to visit the “great Matrapolis” of London.13

Such complacency would not endure for long. Over the following months and years, Washington’s English agents tested his patience with apologies that the “Crop of Tobacco in General was but ordinary,” that sales were “too light,” and that “it gave us a good deal of trouble to get the price it sold for.” By the early 1760s, tobacco was unmistakably failing as a trade commodity. The primitive farming practices of the day played a role in the decline. Tobacco rapidly drains soil fertility, and although Washington directed regular crop rotations the nutrient-poor and clayey Mount Vernon land soon lost its potency. All he could do was let old fields lie fallow—for up to twenty years—and clear new land for planting. That practice could not continue indefinitely.14

Nor could he rely on the sweet-smelling tobacco from the Custis plantations to take up the slack. Plantation manager Joseph Valentine wrote Washington on August 9, 1760, that the tobacco there had been “drownded” by heavy rains. Drought followed in 1762, forcing Washington to write to Cary on June 20: “We have had one of the most severe Droughts in these parts that was ever known & without a speedy Interposition of Providence (in sending us moderate & refreshing Rains to molifie & soften the Earth) we shall not make one Oz. of Tobacco this Year.” Or, as he wrote with bitter sarcasm to his friend and relation Burwell Bassett on August 28: “Our growing Property—meaning the Tobacco—is assailed by every villainous worm that has had an existence since the days of Noah (how unkind it was of Noah now that I have mentioned his name to suffer such a brood of Vermin to get a birth in the Ark).” Plenty of other tobacco was damaged in transit or lost to French predators or bad weather, and insurance was expensive—another knock against an international trade that had at first seemed so lucrative.15

Washington also began to suspect that British tradesmen were hoodwinking him, for price tags on imports rose even as tobacco prices wilted. “I cannot forbear ushering in a Complaint of the exorbitant prices of my Goods,” he complained to Robert Cary. It was shoddy merchandise too, and sometimes even—horrors—out of date. “You may believe me when I tell you,” Washington griped, “that instead of getting things good and fashionable in their several kind we often have Articles sent Us that could only have been used by our Forefathers in the days of yore.” It appeared that British merchants were palming off their refuse for the export trade while deliberately jacking up prices as much as 20 percent.16

Washington hated the thought of being cheated. In desperation, he told his agents to order goods from tradesmen without revealing that they were for export. The ineffectiveness of this prescription solidified his suspicion that agents and tradesmen were working in tandem. A creeping resentment against the mother country stole into his mind.

Peace seemed to promise a better future. At the end of the French and Indian War, Washington looked forward to the prospect of free and uninterrupted commerce. “We are much rejoiced at the prospect of Peace,” he told Cary, “which ’tis hoped will be of long continuance, & introductory of mutual advantages to the Merchant & Planter, as the Trade to this Colony will flow in a more easy and regular Channel than it has done for a considerable time past.” Experience quickly showed, however, that in the colonial system trade was not free. America served as a source of raw materials for Great Britain, and as a market for British manufactured goods. Imperial regulations dictated that this should remain so in perpetuity.17

American entrepreneurs like Washington did not enjoy unfettered access to the world market and could not react freely to the laws of supply and demand. American exporters had to ship goods demanded by Continental European markets to Great Britain, where they were subject to heavy duties and tolls before being transmitted through middlemen—of course at higher prices—to the Continent. Likewise, European exports to America had to go through Great Britain, again incurring duties and tolls, before traveling on British ships to America. British merchants were subject to no such liabilities. The system was designed to protect and enrich them, not their American suppliers.

The colonial system humiliated Americans and stifled their natural yearning toward prosperity. Some began to face not just stasis but poverty. By the mid-1760s, Washington’s accounts were falling out of balance. Low tobacco profits were only part of the problem. Upkeep and repairs to Mount Vernon led to a steady flow of heavy expenses. So did his proclivity for purchasing land, which brought his total holdings to 9,381 acres by the summer of 1763. Washington’s excessive lending to family and friends—a habit he never entirely cured—also came back to bite him, as debtors kept finding excuses to delay repayment. And as the prices of imports continued to rise, so did his debts. These became worse every year until 1764, when he discovered to his alarm that he owed £1,800 to Cary & Company alone. With perhaps the greatest sense of shame he had felt since the surrender at Fort Necessity a decade earlier, Washington penned an abject letter of apology to Cary, confessing that it is “an irksome thing to a free mind to be any ways hampered in Debt.”18

The situation was especially galling because in 1762 Washington had finally come into his own as the master of Mount Vernon with the death of Lawrence’s widow. In most respects it was a dream fulfilled. There now rose before him, however, the prospect of becoming what he had long despised—a profligate, debt-ridden planter. Washington often bought lottery tickets for “prizes” from the property of heavily indebted fellow planters and merchants seeking to liquidate their estates, and might well have wondered whether he would soon be selling tickets instead of buying them. Never, though, did he blame his predicament on his own management or open-handed spending. Instead, he grew convinced that the unequal colonial relationship with Great Britain placed an unfair economic burden on American planters.

Washington was slow to change his personal habits. His heavy spending on luxury goods, including large quantities of wine and other alcoholic beverages, reflected not just his and Martha’s personal tastes but his belief in and enjoyment of entertaining. Until his later years, when the cares of public life had worn him down, Washington was known as a genial and gracious host who danced well, conversed freely—especially with the ladies—and spent lavishly to ensure that his guests enjoyed themselves. Foxhunting, which Washington enjoyed, was another social function that made up part of the display. Always, though, his parties and other events served a purpose.

In his early days visiting Belvoir, Washington learned how balls and other less formal gatherings—including even cockfights and card games—served to maintain the social and business relationships so vital to the gentry. Such events took on added importance during the political campaigning season, when candidates were expected to treat voters to a good time in the form of music, games, food, and, above all, rivers of alcohol. In the days-long festival preceding his first election to the House of Burgesses in June 1758, Washington paid £39 out of his own pocket for 160 gallons of booze. During the polling for his reelection in May 1761, he navigated the surging crowd at a cockfight to press hands, show his affinity for the common people, and get out the vote.

Writing in his diary on April 9, 1760, Washington recorded the arrival of one Doctor Laurie, “I may add Drunk.” In an age of prodigious alcohol consumption and widespread alcoholism, such encounters were all too common. Though no alcoholic, Washington drank freely if not prodigiously. Later in life he would develop a fondness for wine, particularly the fortified Madeira variety.19

Domestic production intrigued him as well. Just before the onset of the Revolutionary War, he invested £50 in Italian wine merchant Philip Mazzei’s project to establish an experimental agricultural venture near Monticello “for the Purpose of raising and making Wine, Oil, agruminous Plants and Silk.” Mazzei’s venture failed, but Washington proved prescient in his prediction that “from the spontaneous growth of the vine, that the climate and soil in many parts of Virginia were well fitted for Vineyards & that Wine, sooner or later would become a valuable article of produce.”20

As a young man, Washington’s alcoholic beverage of choice was beer. For a time he even experimented with brewing it. A recipe for “Small Beer” appears in his memorandum book of 1757:

Take a large Siffer full of Bran Hops to your Taste. Boil these 3 hours. then strain out 30 Gallns into a Cooler put in 3 Gallns Molasses while the Beer is Scalding hot or rather draw the Molasses into the Cooler & Strain the Beer on it while boiling Hot. let this stand till it is little more than Blood warm then put in a quart of Yest if the weather is very Cold cover it over with a Blanket & let it work in the Cooler 24 hours then put it into the Cask—leave the Bung open till it is almost done woring—Bottle it that day week it was Brewed.

Nothing came of these experiments—possibly, as modern duplications of his recipe indicate, because George Washington brand beer was awful stuff—and he ultimately relied on others to cater to his needs. He preferred his beer good and strong—preferably porter—but sampled a good number of varieties.21

Domestic brews were available in places. The brewer John Mercer of Frederick County supplied Washington with a cask of beer for almost £4 in April 1768. Imports, however, were usually of higher quality. London brewer Benjamin Kenton sent him a hogshead of “fine old Porter” for £2 5s in March 1760, and Londoner Thomas Dale shipped four casks of “Dorsett Beer” (a staggering 492 bottles) to Mount Vernon in April 1762. Here too, however, Washington discovered that British merchants were not always honest, and that the long route for goods from London to Alexandria presented ample opportunities for accident and thievery. On July 26, 1762, he eagerly opened a cask of porter and three casks of Dorsetshire beer only to discover that they contained dozens of broken, partially full, or empty bottles.22

In the House of Burgesses, delegates generally behaved with decorum, although when deliberations ended they adjourned to local taverns for long nights of gossip, gambling, and drinking. Washington reveled in these affairs but diligently carried out his legislative duties, which included frequent attention to matters concerning the domestic and international dimensions of commerce, finance, and trade. His habits of prudence and moderation impressed the burgesses as they carried out their deliberations. Even as tensions with the mother country heated up, radical firebrands were frowned upon. Washington was attentive and deliberate without being dispassionate or detached.

As a burgess he increasingly identified his personal and economic interests with Virginia and, more broadly, America. He did not expect his country to remain in tobacco, or even primarily in agriculture, forever. In the burgesses he advocated schemes to boost domestic manufacture, and he invested small sums of his own money (for he was too prudent not to be cautious) in ventures for the establishment of wine and silk production in Virginia. These were the first hesitant steps toward what would eventually become a public, and for Washington a personal, crusade.

In the House of Burgesses there is no record of Washington getting bent out of shape over political, legal, religious, or military issues. Economic disputes, however, could get him thoroughly riled. This was especially so when the disputes involved British merchants. Washington continued to rely on their services for his own needs, but he had come to distrust them as a body.

In May 1763, British merchants who were creditors to Virginia for French and Indian War debts petitioned the Board of Trade about the Virginians’ irksome habit of paying them in suspect paper treasury notes. Virginia had no choice: because hard currency was so rare and planters lived mostly on credit, there was no way for the colony to pay debts except by issuing increasingly large quantities of paper currency, which the burgesses declared legal tender. The merchants’ demand that debts be paid in sterling was nonsensical since none was available. Eventually, Washington (himself in growing debt to British merchants) warned, such behavior would “set the whole Country in Flames. . . . [T]his stir of the Merchants seems to be ill timed and cannot be attended with any good effects—bad I fear it will.” He stood with the burgesses in resisting any change. Two years later the Stamp Act, coinciding with deepening financial woes that Washington blamed on unfair trade practices, would bring his feelings of resentment against the merchants to a near-fever pitch.23

Washington had to cope directly with the consequences of this controversy. The stubbornness of the burgesses about paper currency annoyed both the royal governor and the British Board of Trade. As a tit-for-tat, when Native Americans began large-scale attacks on Virginia’s frontier shortly afterward, the British government withheld military assistance. Virginia had to raise its own militia to fight the natives, even though the British told the burgesses they could not print paper money to pay the militiamen.

In 1764, Washington was placed directly in charge of the House of Burgesses commission tasked with wrangling a way to pay the soldiers. He had to do so even as Parliament passed, in April, the Currency Act that expressly prohibited the colonies from printing paper currency. To raise funds, the colonials would just have to find hard currency somehow—practically impossible in the prevailing system—or accept further credit and fall even more deeply in debt to the British. The currency crisis profoundly impacted Washington’s thinking, and threatened his fortune. Another year would pass, though, before the Stamp Act set in motion events that would lead to a final break.

AS THE 1760S PROGRESSED, Washington’s mind matured. His education, as we have seen, was practical. No amount of catching up would ever make him an intellectual. Nevertheless, as an adult Washington attained a genius ideally suited to his own and his nation’s future prosperity. Grand ideas counted for little, he understood, without a good deal of plain common sense. He believed in more than a few high-flown principles, such as liberty, justice, and freedom. The difference with Washington was that he realized ideas meant and could achieve nothing without close attention to the minute realities of day-to-day life. If the devil dwelt in the details, so did hope.

As a surveyor, Washington had perfected his knowledge of tools and techniques, becoming a brilliant draughtsman. As a military leader during the war, he had learned to devote close attention to fundamentals, a skill that would become a foundation of future greatness. And as a planter-businessman, he carefully tabulated his profits, investments, and expenses down to the last penny. Like his father in dealing with the Principio Iron Works, George Washington made certain to evaluate a proposition from all the angles before deciding to invest (or sometimes to cut his losses), but once his mind was made up he was methodical and remorseless. Let others deride his attention to detail as mental slowness if they so desired—hasty decisions, he had learned the hard way at places like Jumonville’s Glen, could lead to disaster.

The same practical mindset had helped Washington to understand both that his education was lacking and that he would have to improve it substantially if he was to achieve success in any realm of endeavor. His shallow training in the liberal arts had caused his letters to betray uncouthness that probably led some to dismiss him as a country bumpkin. Now, as an adult in the 1760s, he applied himself to polishing his written and oral communication skills. The results were tangible. His writing ability, including handwriting, grammar, and organization, improved profoundly from 1759 to 1775.

Washington also spent many a quiet hour in his study at Mount Vernon, simply reading. A lifelong news junkie, he perused weekly papers, especially the Virginia Gazette for up-to-date information on business and politics. The Gazette was not just any newspaper—it was the source of information on market prices, currency values, investment opportunities, mercantile activities, ship departures and arrivals, conditions for trade, estate sales, lotteries, and so on. Washington advertised in it regularly.

Books were a growing but not yet primary interest at this stage in his life. He would later write, “I conceive a knowledge of books is the basis upon which other knowledge is to be built,” but a list of the books in his library that he painstakingly compiled in 1764 reveals a collection that was something of a jumble. Most of the volumes had been inherited from the Custis estate and included a good number of classic works of literature and history, as well as many on theology and medicine. To this Washington added a modest collection of bound periodicals and books on agriculture, husbandry, law, geography, travel, and arithmetic as well as a copy of Mr. Hoyle’s Games, no doubt to inform his card-playing. More usefully, he had purchased Henry Crouch’s A Complete View of the British Customs (1731, though he probably possessed a newer edition), containing everything an exporter needed to know about trade with Great Britain.24

This purposefully directed, bricks-and-mortar reading style reflected Washington’s growing conviction that economics was the fundamental reality that underpinned everything else, including politics and war. He had learned this as a soldier, as a burgess, and as a planter. In the political crises that were to wrack the late 1760s and 1770s, Washington would regard his, Virginia’s, and America’s economic and political interests as one and the same. His actions and words demonstrated his belief that political prosperity depended on economic prosperity, and that political freedom depended on economic freedom. Soon enough, he would have to decide whether they were worth fighting for.

BY 1765, WASHINGTON WAS FAR MORE POLISHED and politically astute than he had been when he married Martha. He was also a savvier planter and businessman. Tobacco planting was second nature, and if trade with Great Britain was not equally so, he at least understood how it worked. But change was in the air. Washington’s expensive tastes in consumer goods and land were beginning to haunt him. Expenses rose faster than profits. Merchants charged higher prices for the manufactured goods that George, Martha, and the children desired. Meanwhile, income fell as prices continued to fall even as tobacco harvests repeatedly failed, reducing supply.

A naturally creative man, Washington understood that innovation was a key to getting back on track. But although his available capital for new investments remained adequate, it was steadily shrinking due to his increasing debts. If this continued for much longer, he realized, he would no longer have sufficient capital to diversify away from tobacco even if he wanted to. Wrapped in the leaf’s deadly embrace, his estate would strangle. Financial disaster would be slow but inevitable.

Washington’s mounting worries provoked him to increased frustration with British merchants. He blamed them for his troubles more than he did his own spendthrift ways. Financial uncertainties also coincided with a growing political crisis with the mother country driven largely by questions of debt and trade. By the mid-1760s Great Britain’s national debt approached £130,000,000, and the country owed £4,500,000 worth of annual dues in interest on those debts alone. Much of this debt derived from expenses incurred by the British while conducting far-flung campaigns in North America during the French and Indian War. And even though peace had been concluded in 1763, expenses would remain heavy so that the colonial governments could continue to defend the frontier against Native Americans. Washington and many others had resented the royal proclamation of that year prohibiting settlement beyond the Appalachians, but projects such as the Mississippi Company that assumed massive British military protection for western settlers were shockingly naïve.

What would become known as Pontiac’s War erupted in the Northwest Territories in May 1763 and would last for three years, sucking in thousands more British troops for frontier defense. It was in this context that the British chancellor of the exchequer, George Grenville, rose in Parliament in the spring of 1764 to propose the imposition of a stamp act on the colonies. By its terms, Americans would be forced to use paper—imported from Great Britain, of course—bearing a special revenue stamp for official documents as well as pamphlets, newspapers, and even playing cards. From the British perspective the proposal seemed reasonable. The colonies demanded much, and they should therefore bear part of the burden themselves.

What seemed reasonable or even benevolent from the British point of view looked punitive to the Americans. The new taxes directly reinforced America’s subservient colonial relationship. American assemblies such as the House of Burgesses had been used to thinking of themselves as smaller versions of Parliament with jurisdiction over their own territories. The Stamp Act, ratified in March 1765 and scheduled to enter operation in November of that year, overrode colonial legislative autonomy on taxation even as the Currency Act of the previous year had removed Americans’ ability to control their own currency.

For the burgesses as a body, and Washington as an individual, the time had come to take a stand. In the House of Burgesses, Patrick Henry introduced his Stamp Act resolutions that in effect asserted the colonists’ equality to residents of the British Isles, and thus their right to tax themselves through their own assemblies. In response, the governor dissolved the legislature and called new elections for the summer, providing Washington with an opportunity to move himself closer to the political center of resistance in Virginia. He left his Frederick constituency and campaigned successfully for election in Fairfax. Political opposition to the Stamp Act was not going away.

Even as the burgesses sought to achieve political autonomy over economic issues, Washington issued his own declaration of financial autonomy. In fact, the two processes dovetailed. On September 20, 1765, as he began developing plans to diversify away from tobacco, Washington wrote to Cary complaining about the “pitifully low” sales of his sweet-smelling tobacco in England. His Virginia neighbors, working through other London agents, seemed to be earning more than him even though their tobacco was of worse quality. In addition, English tradesmen still charged Washington ridiculous prices. From where he sat, it looked like Cary was doing nothing to counteract this outrageous behavior. Instead, the agent simply suggested that Washington return overpriced items to London—a process both expensive and ridiculously inconvenient.25

Not just individuals, it seemed, but the British in general were cheating Americans on “matters of the utmost consequence to our well doing.” Consciously or otherwise, Washington increasingly adopted the voice of an aggrieved people as he commenced a strident denunciation of not only the “ill Judged” Stamp Act but all of the recent legislation “and other Acts to Burthen us” that had tightened the squeeze on colonial commerce. Moreover, the measures seemed self-defeating. So far, he pointed out, “the whole produce of our labour . . . has centred in Great Britain.” New taxes would reduce imports and hurt British manufacturers to the detriment of the “Common Weal.” And he hinted at a boycott:

The Eyes of our People (already beginning to open) will perceive, that many of the Luxuries which we have heretofore lavished our Substance to Great Britain for can well be dispensed with whilst the Necessaries of Life are to be procured (for the most part) within ourselves—This consequently will introduce frugality; and be a necessary stimulation to Industry—Great Britain may then load her Exports with as Heavy Taxes as She pleases but where will the consumption be? I am apt to think no Law or usage can compel us to barter our money or Staple Commodities for their Manufacturies, if we can be supplied within ourselves upon the better Terms.26

What else had Washington done over the past five years but expend his “Substance”—the produce of his lands—to Great Britain in return for overpriced “Luxuries” that he was well aware he could do without?

Resistance to these policies did not just represent a protest of the aggrieved. On the whole, it resulted from people thinking not negatively but optimistically. Americans sensed instinctively that they were on the verge of great things—in modern parlance, that their economy was approaching takeoff. The mother country itself provided the inspiration. Under the right conditions, the opportunity was there for America to enter into a whole new phase even as Great Britain had reached the height of an Agricultural Revolution and was in the first throes of the Industrial Revolution. It was no secret that the boom in British agricultural prosperity with the adoption of better farming methods and new technologies had enriched a whole generation of entrepreneurs with ample capital to invest. As investment led innovation and further promoted prosperity, a chain reaction seemed under way. The growing sense of excitement transmitted itself across the Atlantic. American entrepreneurs wanted to join in and share the prosperity. Instead, even as they saw the first glimpses of daylight, they were manacled with onerous restrictions that would force them at best to endure decades of incarceration in an agricultural backwater, and at worst to enter a whirlpool of debt slavery.

Public self-criticism was not in Washington’s line. Privately, however, he recognized that his own spending habits had helped to reinforce the problem. He was not the only one to feel this way. In the aftermath of the Stamp Act, which Parliament grudgingly repealed in March 1766, Americans everywhere were looking at how their addiction to imported British goods made them slaves of the colonial system. Just as later generations were transfixed by the catchphrase “Buy American,” so were the colonials of the 1760s and 1770s. Wearing homespun rather than imported fineries became a matter of pride. At Princeton University (then the College of New Jersey), undergraduates such as James Madison and Henry (later “Light Horse” Harry) Lee pledged their honor to don only American-made clothing.

Old habits die hard, however, and domestic manufacture, neglected for so long, could not be conjured into existence overnight. For many years Washington had spent a good deal of his income on baubles and fripperies. In the morally simplistic thinking of his youth, this had been both a just reward for hard work and prosperity and a necessity to maintain his social standing. But his growing debt made him aware that he was projecting a prosperity he did not in fact enjoy, and the specter of crushing debt and possible bankruptcy, bitterness against British agents and tradesmen, and his growing political awareness convinced him it was time for a change. Henceforward the goal would be self-sufficiency.

The first order of business was to decide how to replace tobacco. Parliament had issued a bounty for American production of hemp and flax. As with other American-produced raw materials, these were to be destined primarily for British markets and the manufacture of rope and cloth. Washington was briefly intrigued with the idea, and asked his agents to tell him what prices he could expect to fetch “as they are Articles altogether new to us & I believe not much of our Lands well adapted for them, and as the proper kind of Packages, Freight, & accustomed charges are little known here.” The prospect of engaging once again in a relationship of dependency with untrustworthy British agents, merchants, and tradesmen cannot have appealed to him. Nevertheless, he experimented with both crops for a time after 1765.27

After careful consideration and extensive research, however, Washington decided to turn his estate over to wheat. There were many considerations behind the decision, not least among them being that although some of his wheat and flour would be destined for overseas markets, he did not have to deal with British merchants directly. Instead he contracted, beginning in 1764, to sell his wheat to American merchants in Alexandria. In following years he simply dealt with merchants in any location who could offer him the best prices.

The changeover involved some expense—fields and farms, buildings and equipment, would have to be reconfigured. But the benefits multiplied in ways that he could not have foreseen immediately, especially with respect to labor. Tobacco had been very labor-intensive, absorbing much of the time and energy of his slaves and white workmen. Wheat, relying more heavily on animal power, did require the devotion of more resources to livestock (and especially the growth of corn and other plants for fodder), but it freed his workers to do other things. This in turn furthered Washington’s dual goals of reducing expenditures and increasing his economic self-sufficiency.

The changeover was extremely rapid. In 1764, his estate produced 257 bushels of wheat; in 1766, 2,331 bushels; and in 1769, 6,241 bushels. By 1774, he could truly say that “the whole of my force is in a manner confined to the growth of Wheat, & Manufacturing of it into Flour.” By 1766, he had eliminated tobacco from his Mount Vernon farms, although he would continue to raise a small crop from rents and his Custis lands until the 1770s. Even so, tobacco production on the Custis estate fell from 133 hogsheads in 1763 to 51 hogsheads in 1767.28

Once he committed to wheat, there would be no turning back. Improvement was rapid but the statistics did not suffice to satisfy Washington’s ambitions. He wanted to maximize production. For this, experimentation and investment were essential. Experimentation particularly tantalized Washington, who possessed a scientific bent of mind.

Back in 1760, he had laboriously constructed a large wooden box divided into ten compartments. Into each of these he shoveled soil, being certain to take all of the soil from the same field “without any mixture.” One box he left unenhanced. Into each of the others he added a different kind of fertilizer, including horse, cow, and sheep dung; “Mud taken out of the Creek”; “Riverside Sand”; clay; “Black Mould”; and marl (clay with silt of fossil shell or lime). To ensure regularity, Washington mixed the fertilizers and soil “in the most effectual manner by reducing the whole to a tolerable degree of fineness & jumbling them well together in a Cloth.” Into each compartment he planted three seeds each of wheat, oats, and barley, using “a Machine made for the purpose,” to ensure that they were “all at equal distances in Rows & of equal depth.” Then he sat back to wait, watering each of the compartments equally for two weeks. On May 1, he evaluated the experiment and concluded that sheep dung and “Black Mould” were the most productive; but the experiments would continue.29

Machinery fascinated Washington. He was aware of innovations developed overseas from reading the newspapers. Though he also read plenty of books on the subject, he always preferred using his hands. On any given day in the 1760s he could be found puttering about the workshop, often side by side with a slave, trying out some new contraption aimed at improving production.

He began with the most fundamental of all agricultural implements: the plow. Shortly after moving to Mount Vernon, he worked on designing a new model plow partly of his own design. The gadget didn’t work at first, but after more tinkering he proudly went out to draw it behind his large bay mare. Over the following years he built more plows and had them used across all of his fields while still seeking to improve them. Experiments also continued on a new harrow for his grain.

Larger labor-saving devices intrigued Washington, complex though they were by the standards of the time. In 1764 he investigated reports of an “engine” that had been developed for tearing up trees by the roots, allowing for more rapid clearing of land. He also looked into developing a forge and ironworking industry on his estate, although nothing would come of this until after the Revolution.30

The most important and complex machinery at Mount Vernon was in the gristmill. The building was originally located on the Mill Tract east of Dogue Run about two miles northwest of the mansion. It was an elderly construction, having been acquired by Lawrence in 1738 when he bought the surrounding property. He then transferred it to his father. When Augustine died in 1743, it reverted to Lawrence and he made some improvements to it, expanding the property for the growing millpond. By the time George moved to Mount Vernon with Martha in 1759, though, the mill was little more than a junk pile. Watching its operation closely, Washington was shocked to discover that it took the old machinery almost an hour to grind a single bushel of grain.

At first all he could afford were stopgap repairs. Characteristically, he brought in expert help but participated personally in every undertaking, whether digging a new mill dam alongside his slaves and hired labor or working alongside his carpenters to replace decayed machinery or make delicate adjustments to the mill operations. In so doing, he acquired a minute understanding of how everything worked.

With the changeover from tobacco to wheat, updating the gristmill became imperative. After a thorough inspection of the old building, Washington concluded it was hopeless. Instead, in 1769 he decided to construct a new mill half a mile downstream and on the other side of Dogue Run. He chose the site with the expert advice of John Ballendine, a successful local mill owner, and then devised a plan for constructing the building. Traveling to the falls of the Potomac, Washington selected large river rocks, and had workers excavate and float them down to Mount Vernon. These would serve as the building’s foundation. He directed others to quarry stone for the walls, and cut timber from his estate for the roof and interior. Another team, also under the master’s close supervision, dug the millrace.

The equipment was expensive, but Washington did not scrimp. His goals were loftier than just grinding his own grain; he also intended to earn profit from his neighbors by constructing a modern mill that could grind theirs as well, producing varying grades of meal for added profit. To that end, instead of purchasing the substantially cheaper but inferior-quality local millstones, he had two stones imported from France. These were not only superior but the best to be found anywhere, since they were exceptionally hard and held a good sharp edge for many years. The flour they produced would be the best in northern Virginia, and would command commensurate prices. It was worth the investment of £38, almost twice what he would have paid for local stones. By the time the stones were in place and the new mill was fully operational in 1771, Washington’s own wheat production was at its peak and he had a highly profitable and growing concern of domestic manufacture. Here too, though, experiments would continue, both with different kinds of wheat and other grains and with different means of harvesting and grinding it.

Wheat and flour could be sold domestically far more easily than tobacco, so that he could operate outside the colonial system. But American merchants were not necessarily easier to deal with than British ones. As he moved over to wheat, the first major firm Washington contracted with for sale was Carlyle & Adam of Alexandria. The relationship quickly went sour, however, and on February 15, 1767, Washington sent the unlucky partners one of the angriest and longest letters he ever wrote, lashing them savagely for their inability to procure a fair price for his wheat. At its end, he promised never to write them again. Ironically, though, Washington and the partners soon settled their differences. Carlyle & Adam would serve for many more years as his primary contractor for wheat and flour. A primary difference between the Alexandria merchants and the British, of course, was that the former were available for personal interaction while the latter were not. Also, with less money on account with the likes of Cary thanks to the decline of tobacco, Washington could concentrate his British purchases on necessities rather than luxuries.

As his productivity multiplied—some twenty-five times by the end of the 1760s—Washington’s flour production became a going concern. His finely equipped mill ground grain for other farmers at a fee, and plans were under way to construct similar operations in other parts of Virginia. Quantity, however, could not be allowed to impinge on quality. Washington’s insistence on high production standards paid off as his “G. Washington” brand of flour became known for its reliable superiority. A Norfolk merchant reflected the views of his peers in gratefully telling Washington that his brand had “the preference of any at this market.”31

By the 1770s, Washington was selling corn and meal for slaves in the West Indies. Even sailors gnawed Washington-brand biscuits as they plied the Atlantic trade. Here too, not all his experiences were positive. In 1772, Washington formed a partnership to sell flour refined at his and others’ mills in the West Indies via a Jamaican merchant. Unfortunately, the incompetence of his supercargo Daniel Jenifer Adams—whom Washington called a “worthless young Fellow”—doomed the venture. Expecting Adams’s ship to sink, he abandoned it quickly in an eighteenth-century harbinger of the modern “fail-fast” technique—but not before losing money that he recovered partly by seizing 500 acres of Adams’s land.32

Missteps of this sort were inevitable companions of bold entrepreneurship. But though the risks were substantial, the opportunities were too good to ignore. Increasingly large numbers of Washington’s countrymen followed his example or, more often, set examples of their own. Those willing to forego tobacco found that their profits went to their own pockets instead of to the British. As more planters moved to wheat and other profitable crops, America experienced an economic explosion. Productivity of staple goods boomed while enterprises for preparing, marketing, and transporting them via land or sea appeared in towns like Alexandria. As the American economy grew in size, however, the colonial shackles restraining it squeezed all the more tightly.

THE MOVE TO WHEAT SPURRED MOUNT VERNON’S TRANSFORMATION. Riding around the estate in 1759, Washington had scanned a vista awash in green, and would not have heard much more than birdsong, the clop of his horse’s hooves, and the calls of men in the fields. The same scene a decade later presented him with a bedazzling variety of sights and sounds. Production was everywhere. In the past, Washington’s slaves had depended almost entirely on others to supply their basic necessities, such as food and clothing. Now that they were free of tending tobacco, he expected them to provide for themselves. Fields echoed to hammers and saws as they built and maintained their housing, becoming skilled carpenters and masons. They constructed pens to raise hogs and chickens; tanned hides; cobbled shoes; constructed carts and wagons; cut stones; and made and laid bricks. The blacksmith shop, where a hammer or two had been wont to ring from time to time, now expanded into a hive of activity where skilled men not only shoed horses but also manufactured and repaired tools and household implements of all varieties. Before long, the smithy became a profitable enterprise. All of these crafts took training, but because Washington moved quickly over to wheat once he had made the decision to do so, he trained his labor more quickly than many of his neighbors, who now trekked to the Mount Vernon smithy with cash in hand to purchase manufactured goods and services.

As Mount Vernon’s slave population grew, so did the need for clothing. Demand was in fact increasing throughout the region as rising numbers of free and enslaved laborers worked to expand estates. Washington, keenly aware of the growing tide of European immigration, anticipated that the increased demand for standard consumer items like clothing offered him another venue for profit. To that end he hired a supervisor named Thomas Davis to train and oversee a team of women—slaves and indentured servants—to labor in a specially constructed spinning house. Soon Mount Vernon’s spinning wheels and looms were adding their voices to the chorus of industry at the estate. The scribble of Washington’s pen joined in as he took careful records of costs, production, and profit. In his spinning and weaving account for 1768, he noted that his laborers had churned out 1,365 yards of flax linens, woolens, linsey (wool cloth), and cotton fabric during the year. Beneath the account he tabulated what it would have cost him to import and prepare the same amount of material during the same period, and concluded that by manufacturing at home he was saving more than £50 per annum over and above what he earned by selling his excess production to neighbors for cash and barter goods.

The Mount Vernon community now could also take advantage of a rich natural resource close at hand—the Potomac River, abounding with fish. Washington had been sensitive since childhood to the importance of waterways not just as highways of commerce and trade but as resources in their own right. Water had been close at hand where he lived at his birthplace and on Ferry Farm, and fishing was one of his favorite pastimes. The same applied at Mount Vernon, which Lawrence had named after an admiral.

Given his druthers, George would have been a devoted fisherman. Throughout his life he had a particular fondness for fish on the table. In January 1760, he braved bitter weather to trek down to the river landing, where he “Hauled the Sein and got some fish.” Unfortunately, on his return to the landing a thuggish “Oyster Man” ambushed Washington and “plagud me a good deal by his disorderly behavior.” Inwardly seething—his spirits worsened by the fact that Martha and much of the family were sick with measles—George carried his fish home; but when he returned to the landing a few days later, the surly oysterman popped up again, this time accompanied by friends. Washington—whose temper befitted his imposing physique, but who usually refrained from initiating physical combat (especially when outnumbered)—“was obliged in the most preemptory manner to order him and his Company away which he did not incline to obey till next morning.”33

With the oysterman out of the way, Washington marveled at the river’s bounty. His diaries and letters abound with references to teeming fish. “The Sturgeon are now jumping,” he told Charles Washington on August 15, 1764; and on May 16, 1768, he spent the day “Fishing for Sturgeon from Breakfast to Dinner” although alas he “catched none.” On April 22, 1769, his sole diary entry expostulated on how “The Herrings run in great abundance.”34

Exploiting this resource was initially a simple matter. He would watch attentively as two men rowed out into the channel, drawing out behind them a seine up to 450 feet long, weighted with lead on one side and floated by corks on the other, and tied on each end with hauling ropes. Once the seine was fully deployed, men on shore would pull in the hauling ropes. Thousands of fish trapped in the net would then be pulled ashore, where slaves would wade in with bushel baskets to harvest the catch. Some fish ended up on the evening’s table in the mansion house and in slave quarters, but slaves would preserve the majority of the catch by cleaning and gutting the fish, salting them, and packing them in barrels either for future use at Mount Vernon or for sale in Alexandria.

With increasing labor and financial resources available to him after the switch away from tobacco, Washington expanded the fishery. His slaves added shipbuilding to their other skills as they constructed boats and even a fine schooner under the master’s supervision. Slaves and hired boatmen manned this small fleet (and eventually operated a river ferry), exponentially increasing production. By the 1770s, he was not only selling fish to neighbors but also shipping barrels of salted fish to the West Indies via Alexandria merchants.

Although restrictive British policies continued to create annoyances—forcing him, for example, to bypass fine Portuguese salt for fish-curing in favor of lower-quality Liverpool salt—the fisheries soon became one of his most valuable enterprises. In 1772 alone, his men caught a million herring along with ten thousand shad and other fish; and after meeting the needs of his own community at Mount Vernon, he sold the rest to merchants, clearing a profit of £184. The profits, and fortunately the fish, would remain ample throughout his lifetime. On December 12, 1793, he wrote to the Englishman Arthur Young: “This River, which encompasses the land the distance abovementioned, is well supplied with various kinds of fish at all seasons of the year; and in the Spring with the greatest profusion of Shad, Herring, Bass, Carp, Perch, Sturgeon &ca. Several valuable fisheries appertain to the estate; the whole shore in short is one entire fishery.”35

As for tobacco, it had become a sidelight. British merchants still tried to entice him back into the old system, but he informed one of them on May 5, 1768, that “Having discontinued the growth of Tobacco myself, except at a Plantation or two upon York River, I make no more of that Article than barely serves to furnish me with Goods [and] necessaries wanted for my Family’s use.” In effect, he regarded it as disposable income.36

That spring and summer, tobacco enjoyed a brief spike in prices, and Washington wrote to Cary of his belief that “Tobacco would rise & sell almost as high as it ever had done, was as clear to me as the Sun in its meridian height.” Instead of rushing to plant more leaf, however, he just exploited the temporary windfall as an opportunity to purchase extravagances that he would not otherwise have considered, such as a secondhand English chariot that he ordered through Cary. His correspondence with British merchants from then on concerned only his shrinking tobacco crop and the small quantities of hemp and wheat that he also produced for export to England.37

Washington had never been busier—or happier. Though not exactly a workaholic, he was industrious and the sensation of expansion and profit gave him deep satisfaction. Instead of joining in the public craze for consumer goods, he profited from it. His success in this arena helped to compensate for his disappointment at Martha’s not bearing him any children. Another cause for satisfaction was the revelation that by the early 1770s he was free of debt. The income from Mount Vernon’s many industries provided Washington with a modest but growing source of capital that allowed him not only to throw off the British credit system but also to look to other investment opportunities. Almost instinctively, he looked to the west.

WASHINGTON’S FINANCIAL INTERESTS transcended the boundaries of his far-flung and growing estate. Even as he attempted to make his farming and trading interests more profitable, he sought to buy, sell, and invest wherever the winds of commerce and his inclinations took him. His goal remained simple: to get rich as quickly as possible. He was not the only one to think that way, and in late colonial America there were more investment schemes available than a planter could shake his cane at. But when it came to large sums of money, Washington was an educated investor rather than a gambler. When opportunities arose, he would take their measure firsthand rather than relying on biased third-party information.

Extended interests also converged with Washington’s vision of the physical expansion and financial future of America as a whole. Above all, land was still a primary commodity of economic growth. It could be bartered, rented, settled, and developed in a variety of ways. Commercial towns could be founded and profits controlled. Opportunities for expansion abounded—at least insofar as the British government permitted their exploitation.

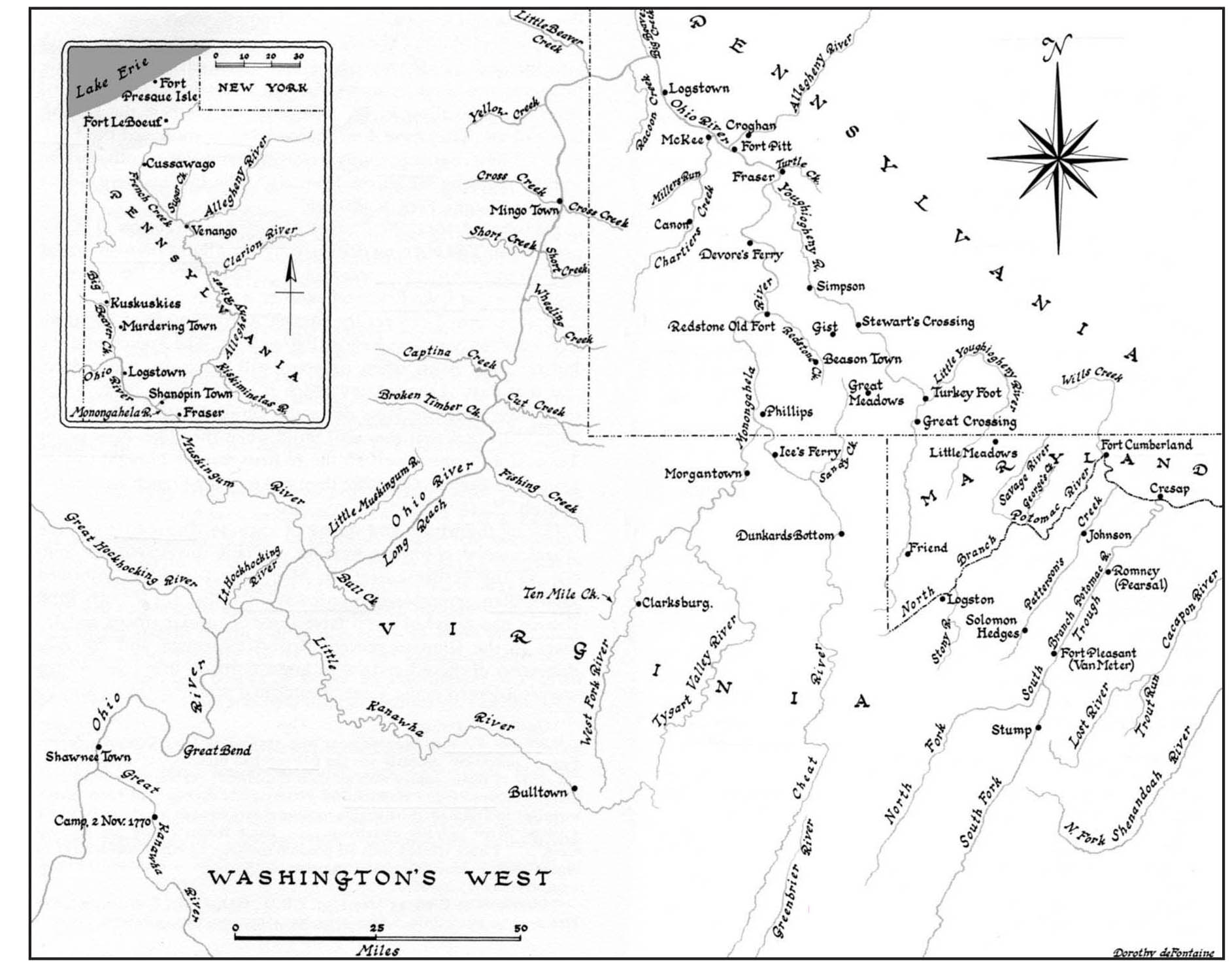

In May 1763, at the height of spring and before the flies and mosquitoes began to frolic, Washington and a small band of “adventurers” visited the Great Dismal Swamp. This aptly named quagmire was an odd feature on the landscape. It was higher than the surrounding land, so water drained out of it rather than into it. Other than that it was like a typical swamp, only a hundred times worse. Straddling the Virginia–North Carolina border along a twenty-mile stretch from south of Chesapeake to near present-day Elizabeth City, North Carolina, it was choked with standing cypress and white cedar trees surrounded by thousands of rotten trunks and branches clogging the muck amid clumps of reeds. But it had potential for those with eyes to see.

Taking a break from the General Assembly then meeting in Williamsburg, Washington and his friends Fielding Lewis, Burwell Bassett, and Thomas Walker—all young and equally bent on profit—rode south from Suffolk along the western edge of the swamp. At one point they dared to venture half a mile into the stinky expanse as their horses sank up to their fetlocks in the muck. They withdrew with some difficulty and continued their circuit east, crossing a small bridge across the Perquimans River and turning north up the great swamp’s eastern edge. Along the way there would have been plenty of young men’s banter, but they also took careful notes on water drainage and soil quality.

Far from being repelled by his little adventure through the wastes, Washington was refreshed and intrigued. Some corners of the swamp had already been drained, cleared, and settled on what he observed to be “prodigious fine land.” Given patents to the wasteland and the right of passage across already-settled territory, Washington and his friends were convinced they could make a profit from it. The soil seemed “excessive rich,” and the thousands of trees and logs were as good as money in the bank. While the land was being drained, they could harvest and sell the lumber, and once the draining was done, they could farm the rest to their mutual profit. Washington imagined the construction of a canal from the swamp to Norfolk that could both drain the morass and serve for commerce.38

The explorers joined with outside partners in forming a company optimistically dubbed “Adventurers for Draining the Dismal Swamp” and successfully petitioned the Assembly for the right to construct canals and causeways across private land to facilitate their work. Legal and practical difficulties would eventually sink the venture in a morass as intractable as the swamp itself. Washington nevertheless invested enough money into it to secure the rights to 4,000 acres of swampland. He would hold on to these until 1795, when he sold them to “Light Horse” Harry Lee.39

Just a few weeks after returning from this trip, on June 3, 1763, Washington joined another hardy band of “adventurers” in an organizational meeting of the Mississippi Land Company. The objectives of this company were considerably more grandiose than those of the Dismal Swamp Company. With the disappearance of the French from the Mississippi territory at the end of the war, land there seemed ripe for the taking. Property along the Mississippi looked especially attractive because of the advantages the river offered for interior and exterior trade and commerce. The adventurers invested funds to appoint an agent who would travel to England and secure rights to enough territory along the river to provide 50,000 acres per man. The king, it was assumed, would graciously provide military protection against the Native Americans, whom the settlers would brush aside before clearing and developing their land.