NEWS OF FRENCH INTERVENTION IN THE SPRING OF 1778 generated a wave—all too fleeting, alas—of popular joy. Americans dreamed of the arrival of a French army that would drive the British from the continent while the French Navy routed them from the high seas. Washington’s official camp celebration, with its parades and artillery salutes, was intended to reinforce that impression. His immediate hopes, though, were economic. Most obviously, the United States could look forward to an influx of French loans and supplies. But Washington also rejoiced at receiving “a clear proof of the intention of France to encourage and protect our trade” with the West Indies and Europe, and looked forward to the boost that public confidence would give to Continental currency. “The favorable news from Europe,” he wrote optimistically on May 15, “has already begun to produce a visable effect on the value of paper money . . . that . . . will extend its influence and reduce the price of horses and every other article.” Meanwhile, he expected the British to find it increasingly expensive to carry on a struggle that now extended beyond North America to the West Indies, Europe, and even Asia.1

With three years of war under his belt Washington had learned a great deal about the limits of patriotism, and he incorporated these lessons in his revised strategic vision for victory. He summed up his approach in a letter of April 21 to Virginia planter John Banister:

Men may speculate as they will—they may talk of patriotism—they may draw a few examples from ancient story of great atchievements performed by it’s influence; but, whoever builds upon it, as a sufficient basis, for conducting a long and bloody War, will find themselves deceived in the end. We must take the passions of Men, as nature has given them, and those principles as a guide, which are generally the rule of action. I do not mean to exclude altogether the idea of patriotism. I know it exists, and I know it has done much in the present contest. But I will venture to assert, that a great and lasting War can never be supported on this principle alone—It must be aided by a prospect of interest or some reward. For a time it may, of itself, push men to action—to bear much—to encounter difficulties; but it will not endure unassisted by interest.2

This was no declaration of cynicism, or recognition if not endorsement of selfishness. That is not what Washington meant by “interest.” Instead, he pointed to the basic human calculus of expense and reward. Patriots and Loyalists, he believed, were not born but created by virtue of their experiences and perceived interests. The categories were not rigid but ever-changing. Today’s popular war against British rule might well have become tomorrow’s revolt against Congress if personal sacrifices for independence seemed to go for naught.

Even French intervention, then, might avail nothing if the American people lost the sense that they had a personal stake in success, and lost confidence in victory. “Men are naturally fond of peace,” he told Banister, and there were clear signs “that the people of America, are pretty generally weary of the present war.” Many of them doubtless would be willing to come to an “accommodation” with the enemy “rather than persevere in a contest for independance.”3

With that in mind, it was essential to place the army upon “a substantial footing”—as a means not just of securing victory in the field but of encouraging the people. “This will conduce,” he wrote, “to inspire the Country with confidence [and] enable those at the head of affairs to consult the public honor and interest, notwithstanding the defection of some and temporary inconsistancy and irresolution of others, who may desire to compromise the dispute.” At the same time, and more important, it was essential to educate the people that their personal interests lay in “Nothing short of Independence”—not least because independence held forth the prospect of “unrestricted commerce.”4

Currency was the bellwether of public confidence. Building confidence strengthened the currency and vice versa. After 1778, this knowledge increasingly defined Washington’s military strategy. In June 1778, British forces evacuated Philadelphia and marched in sweltering heat across New Jersey with the Continental Army in their tracks. No one told Washington that he had to attack the British—the prospects for cutting them off were almost nil—but he did so anyway. The Battle of Monmouth on June 28 was essentially a draw, but in its aftermath Washington and his officers did everything in their power to spin it as an important victory. They did so partly to reinforce the commander in chief’s authority, but primarily to inspire public confidence.

Afterward, the British hunkered down in New York City and refused to engage militarily with the Americans on a large scale in the mid-Atlantic region, although the threat that they would do so—particularly up the Hudson toward West Point—always hovered overhead. The following months passed for Washington in grinding frustration. Ennui, he feared, could inflict as much harm as outright defeat, perhaps even more so—eroding confidence and endangering the economy, and thus independence, in the long run. Troubling financial signs reinforced his fears as the currency once again neared total collapse.

To Washington it seemed likely that time, despite French intervention, would work against American prospects for independence. “Can the Enemy prosecute the War?” he asked his friend Gouverneur Morris on October 4, 1778:

Can we carry on the War much longer? certainly No; unless some measures can be devised, and speedily executed, to restore the credit of our Currency—restrain Extortion—and punish Forestallers. Without these can be effected, what funds can stand the present Expences of the Army? And what Officer can bear the weight of prices, that every necessary article is now got to? A Rat, in the shape of a Horse, is not to be bought at this time for less than £200—A Saddle under Thirty or forty—Boots twenty—and Shoes and other articles in like proportion! How is it possible therefore for Officers to stand this, without an Increase of pay? And how is it possible to advance their pay, when Flour is selling (at different places) from five to fifteen pounds pr Ct—Hay from ten to thirty pounds pr Tunn—and Beef & other essentials in this proportion. The true point of light then, in which to place, & consider this matter, is not simply whether G. Britain can carry on the War, but whose Finances (theirs or ours) is most likely to fail.5

Washington was not the only one concerned that financial ruin would herald total defeat. Up to now Congress—still stubbornly thinking in the short term despite the commander in chief’s warnings—had attempted to curry popular support for the war effort by keeping the tax burden light. In December 1778, however, the delegates voted to enact a new war tax of $15 million. This, President of Congress Henry Laurens informed Washington, would hopefully return “many of us to first principles from which we have been too long wandering.” Though “almost intolerable,” he expected the tax to “rouse & animate our fellow Citizens” by forcing them to economize and eliminate waste and showing “the necessity for consolidating our strength, as well as the impropriety & danger of new expensive Military enterprizes.” Of course, it might also convince them that the war was too expensive to continue.6

French financial aid, both Laurens and Washington recognized, was a double-edged sword. “I warned my friends against the danger of Mortgaging these States to foreign powers,” Laurens wrote. “Every Million of Livres you borrow implies a pledge of your Lands.” Washington agreed, arguing that loans should be kept to a minimum and that even French military aid should be welcomed with care. It was for this reason among others that he rejected in 1779 a proposal for a prohibitively expensive Franco-American invasion of Canada. Almost instinctively, he returned to the old mantra he had learned in childhood. Economize, economize, economize, he proclaimed: “retrenching our Expences and adopting a general system of Oeconomy which may give success to the plans of Finance Congress have in contemplation and perhaps enable them to do something effectual for the releif of public Credit and for restoring the Value of our Currency. . . . The most uniform principle of Oeconomy should pervade every department.”7

But nothing seemed to work. By the spring of 1779, inflation once again clutched the economy in its grips. “Speculation—peculation—engrossing—forestalling—with all their concomitants, afford too many melancholy proofs of the decay of public virtue,” Washington wrote to Massachusetts Patriot James Warren on March 31; “and too glaring instances of its being the interest & desire of too many, who would wish to be thought friends, to continue the War.” There was nothing wrong with honest profit; but rampant speculation in pursuit of “a little dirty pelf” out of a “lust of gain” was among the most “monstrous evils” imaginable. “Let vigorous measures be adopted,” he begged Warren, “not to limit the price of articles—for this I conceive is inconsistent with the very nature of things, & impracticable in itself—but to punish speculators—forestallers—& extortioners—and above all—to sink the money by heavy Taxes—To promote public & private Œconomy—[and to] encourage Manufactures.”8

A crushing sense of helplessness engulfed Washington as he watched the currency continue to plunge despite his exhortations. By May 1779 he feared that economically speaking “our affairs are irretrievably lost,” and that “a general Crash of all things” was imminent. But what could he do? The British remained firmly ensconced in New York City, and despite pinprick raids that summer at Stony Point and Paulus Hook—symbolic actions specifically designed to refocus public energy on the war effort—there seemed little prospect of rooting them out. Washington nevertheless determined to try.9

Heavily fortified by land and sea and easily reinforced, New York was next to impregnable. Even if successful, an American assault on it would entail almost unimaginably heavy casualties. Why, then, was Washington so determined to attack it? Was his aggressiveness born of impatience or some sort of mental imbalance? In fact, from his perspective the focus on New York was completely rational. The collapse of the Continental currency—shored up only by massive French and eventually Dutch loans that might reduce the United States to debt slavery if allowed to continue for long—augured in Washington’s view a total paralysis of the war effort, forcing the army to concentrate solely on survival. This in turn would undermine popular support of the war, leading in a viciously spiraling circle to further economic dislocation, unrest, civilian commerce with the enemy leading to the development of pernicious communities of interest, and total defeat.

Washington did not want to risk everything on a single throw of the dice—he feared that he would be compelled to do so. For the remainder of 1779 and into 1780, as the British launched a crushingly successful campaign to conquer the South, and as Washington’s army reeled from mutinies brought on by pay shortages and economic distress, he set the groundwork for an assault that would decide everything in one stroke. The moment appeared to have arrived in the fall of 1779, when a French fleet seemed prepared to anchor off New York City. Washington eagerly mobilized his entire army for an imminent assault on the British entrenchments. When the fleet failed to materialize, he had to go back to biding his time. Still, though, he was prepared to resume the operation in an instant—whether from opportunity or out of final desperation.

THE YEAR 1781 DID NOT DAWN HAPPILY. At Morristown on New Year’s Day, troops of the Pennsylvania line rose up in mutiny. The men were orderly on the whole, but snarled ominously that if their demands for immediate relief were not met, they would push their quarrel with Congress at the point of the bayonet. They then marched to Princeton and made menacing gestures toward Philadelphia. Washington bought them off with honorable discharges and furloughs, only to face another mutiny by New Jersey troops a few weeks later. Alarmed that disaffection was metastasizing throughout the army, he put this revolt down brutally, rounding up the mutineers and forcing the men to execute their ringleaders.

The root causes of disaffection nevertheless remained, and they were predominantly financial. Pay, as usual, was badly in arrears; but that hardly mattered since it was worthless anyway. A horse cost $150,000, almost four times what it had cost a year earlier. Literate soldiers read letters from home telling tales of devastated farms and businesses, and of suffering wives and children. Illiterate soldiers fed on a rumor mill that warned of wholesale economic collapse and eventual starvation.

George Washington as a young surveyor. Library of Congress

Virginia governor Robert Dinwiddie (1693–1770) helped to establish George Washington’s career, first by establishing his career as a surveyor and then by appointing him to military office. National Portrait Gallery

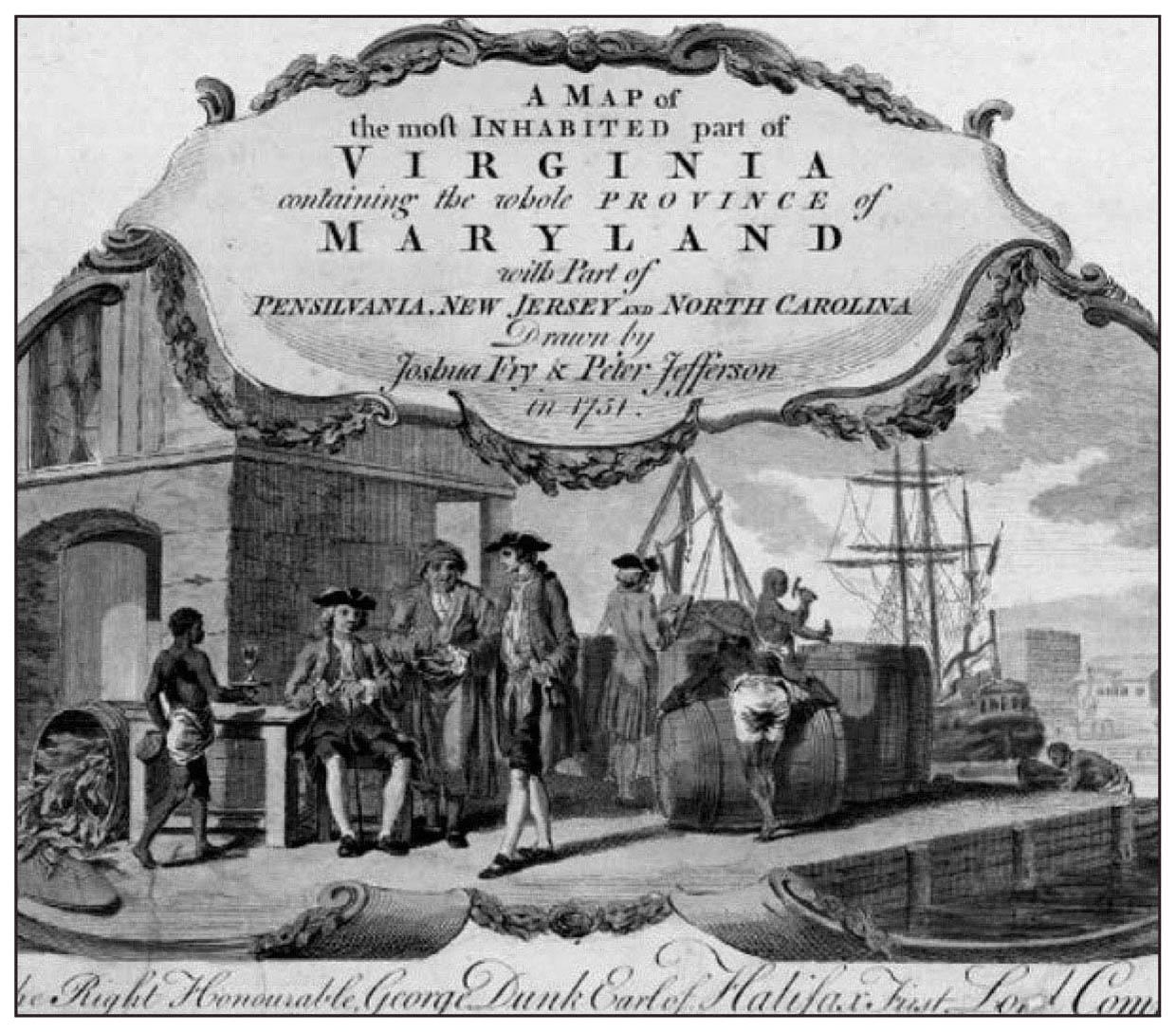

Tobacco hogsheads being inspected and prepared for shipment, from a 1755 map. Tobacco was both the source of Washington’s wealth and an obstacle to his future prosperity. From the 1755 Fry-Jefferson map at the Library of Congress; detail in the lower right.

Martha Dandridge Custis, a wealthy widow, brought more than just money to her marriage with George Washington in 1759. Over the course of their long, loving relationship she proved a steady partner and an able estate manager during her husband’s long absences from home. From an engraving by J. Cheney & J. G. Kellogg in Sparkes, Jered, “The Life of George Washington,” Boston: Tappen & Dennet 1843, “The Cooper Collections of American History”

Robert Morris (1734–1806), who as American Superintendent of Finance after 1781 helped to stave off financial collapse in the waning years of the Revolutionary War. Painting by Robert Edge Pine

Arthur Young (1741–1820), English agricultural innovator and George Washington’s collaborator. National Portrait Gallery

Alexander Hamilton, who as US Secretary of the Treasury from 1789–1795 both implemented and helped to define Washington’s economic policies. Bureau of Engraving and Printing

Meticulous account-keeping, which George Washington practiced throughout his life as in this record from 1788, was an essential element of his prosperity. Library of Congress

George Washington’s plan for his innovative sixteen-sided barn, prepared in 1792. Reproduced in The Papers of George Washington Presidential Series, 11:279; original in Library of Congress

Milling designs patented by the American inventor Oliver Evans formed the basis for Washington’s Mount Vernon gristmill and other highly productive eighteenth-century operations. From The Young Mill-wright and Miller’s Guide, by Oliver Evans, 1795

Washington inspects the Mount Vernon harvest, an 1851 painting by Junius Brutus Stearns. Slavery operated through coercion, removing any positive incentive for industry. Washington eventually came to view it as both morally reprehensible and economically counterproductive. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

George Washington’s meticulously drawn 1793 map of his Mount Vernon farms with notes on their contents. Reproduced in The Papers of George Washington Retirement Series, 4:460–61; original in Henry E. Huntington Library, San Marino, California

Washington was under no illusions about the probable outcome of this miserable state of affairs. At Valley Forge, he had labored hard to establish a community of commerce between the army and the civilian population—a community that left the British on the outside looking in. Now, despairing civilians were not only selling provisions to the British in New York City on a scale never seen before—they were also turning their long-cherished hoards of hard specie over to the British in exchange for desperately needed consumer goods such as clothing and household supplies.

This dangerous—and humiliating—commerce, Washington warned, “serves to drain us of our Provisions and Specie removes the barrier between us and the enemy, corrupt[s] the morals of our people by a lucrative traffic and by degrees weaken[s] the opposition.” Shattering the American system that Washington and others had labored so hard to create, it established new bonds of interest with an erstwhile enemy that might, over time, begin to look like a friend. “Men of all descriptions are now indiscriminately engaging in” commerce with the British, Washington anxiously observed, “Whig, Tory, Speculator. By its being practiced by those of the latter class, in a manner with impunity, Men who, two or three years ago, would have shuddered at the idea of such connexions now pursue it with avidity and reconcile it to themselves (in which their profits plead powerfully) upon a principle of equality, with the Tory.”10

Congress, finally, was doing more than just talk. Early in 1781 the delegates proposed to create ministers for war, foreign affairs, and finance. Some suggested Alexander Hamilton, whose talents “as a financier” had become well known, for the latter office, and Washington extolled his “probity and Sterling virtue.” In February, though, the delegates tapped Philadelphia financier Robert Morris. A successful businessman who had earned a small fortune from privateering, Morris had provided important financial support to Congress and the Continental Army in the winter of 1776–1777. He was also a fervent supporter of free-market advocates who decried Congress’s many ad hoc restrictive measures, such as price-fixing, to shore up the Continental currency.11

After taking the oath of office in June, Morris and a talented team that he assembled attempted to tackle the nation’s many economic problems and in particular to restore its currency. So much damage had already been done that his task was largely hopeless. Nevertheless, by securing more French loans, extending his own personal credit, creating a system of in-kind taxes that allowed farmers to fulfill their obligations to the government with goods rather than specie, and establishing the Bank of North America that advanced perhaps $1 million in loans to the government, Morris was at least able to prevent things from getting much worse.

Washington could not afford to wait and see what Morris could accomplish. Up until now his army had been paralyzed, from both lack of opportunity to smite the British and lack of funding. Enemy advances continued in the South despite hopeful signs at places like Cowpens and Guilford Courthouse. Virginia had now entered firmly in the enemy’s crosshairs. In the winter of 1780–1781, the traitor Benedict Arnold, sporting a general’s commission in the British army after attempting to betray West Point the previous September, conducted raids along the Virginia coast. He sacked Richmond, occupied Portsmouth, and in April torched warehouses full of tobacco at Petersburg. The blow to Virginia’s economy was severe and might have become crippling.

Nor was Mount Vernon safe. In April the British warship Savage appeared in the Potomac below the estate. Soldiers from the ship had already landed on the Maryland side, torching a number of estates there. With plumes of smoke rising high into the sky above the river, the British captain sent a message to Lund Washington promising him to expect the same treatment unless he provided the ship with “a large supply of provisions.” Lund hesitated, whereupon the ship drew closer to shore and the threat was repeated. Terrified, Lund boarded the ship carrying some cooked chicken for the British tars’ enjoyment. The captain praised George Washington’s character and promised that he would never “entertain the idea of taking the smallest measure offensive to so illustrious a character as the General.” Now charmed, Lund returned onshore and sent the British a large supply of livestock and other supplies. The warship then departed, carrying with it seventeen of Washington’s slaves who had taken the opportunity to escape. News of the affair sent George into a rage, though by then there was little he could do but chastise Lund—a catharsis he indulged in freely if fruitlessly. The net effect was to renew the commander in chief’s determination to end the war quickly.12

The means to force a showdown now seemed at hand. In July 1780, a French army under the Comte de Rochambeau had landed at Newport, Rhode Island. Washington conferred with the French general repeatedly and, in a conference at Wethersfield, Connecticut, on May 22, 1781, thought he had convinced him to collaborate in an attack on New York City. An approaching French fleet was supposed to cooperate by blockading the city. On August 14, though, Washington learned that the French fleet under Admiral de Grasse was instead heading for the Chesapeake, where it would bottle up a British force under Lord Cornwallis at Yorktown.

At any other time Washington might have hesitated to change his plans on the spur of the moment, but “Matters having now come to a crisis” he promptly decided to throw the Franco-American army in motion toward Virginia. If this was the only way to force the decision that could end the war before the economy collapsed, so be it. A timely infusion of funds from Morris helped to provide the means. After a long march characterized by impressive logistic efficiency, a troubling and all-too-brief visit to the now run-down estate at Mount Vernon, and a surprisingly short siege, Cornwallis surrendered on October 19.13

WINE FLOWED FREELY AT HEADQUARTERS as American and French officers celebrated the victory, and Washington was the dubious recipient of a hearty series of kisses from the French admiral that left him blushing “like a coy damsel.” He had no way of knowing, though, whether Yorktown was indeed the decisive war-ending victory that he had so avidly sought. The general repeatedly warned his army and Congress about the need to maintain vigilance, but to his chagrin nobody seemed to take him very seriously.14

The following months were anticlimactic, and as 1781 turned into 1782 and again into 1783, Washington’s anxiety increased. Peace negotiations had begun in Paris, but as they continued, the American economy and government seemed to be falling apart at the seams. Back in 1778, the commander in chief had proclaimed the essential need for “Congress to be replete with the first characters in every State.” But by 1783 those “first characters” were gone, leaving behind an assembly of mediocrities who could get nothing done. Congress’s inability to raise funds, thanks to deep financial woes and the recalcitrance of the states, left officers’ pay up to $5 million in arrears and their families pauperized. The delegates could not agree on means to address this, or on a pension establishment that would allow servicemen to get back on their feet after the war. “We have borne all that men can bear,” the officers protested; “our property is expended—our property is expended—our private resources are at an end.” By March they were on the verge of leading the army out of its camp at Newburgh, New York, and marching on Congress.15

Washington’s speech to his officers at Newburgh on March 15, 1783, is one of the great moments in American history. He delivered it with trembling hands, and famously punctuated it by donning spectacles that hearkened back to the years that he had labored to feed and clothe his men and keep them in the field. His message was simple: now was not the time to sacrifice all that they had worked for when peace was in view. True, the army—the government—the economy—had held together by a thread. But they had held. The war had been brutal. Families, as the officers knew too well, had been impoverished. At places like Falmouth and Richmond, much property had been destroyed. But for the most part it had been a limited war. Though weak, the civil polity was alive and stable. With peace, there would be something to build on, a hope for prosperity—not, though, if the country collapsed internally just as it arrived at the threshold of achieving its dream. He asked his officers, then, to “express your utmost horror and detestation of the Man who wishes, under any specious pretences, to overturn the liberties of our Country, and who wickedly attempts to open the flood Gates of Civil discord, and deluge our rising Empire in Blood.”16

Washington’s success in dissuading his officers from rebellion at Newburgh, gaining the necessary time that helped the United States to pull through to the September 1783 Treaty of Paris, was a magnificent accomplishment. Before resigning, though, he left behind one more great public legacy. This was his circular to the state governors of June 8, 1783. In it he expressed the perhaps naïve hope that the nation’s diverse civilian leaders would unite in a vision for the United States in which its people would grow “respectable and prosperous.” The human and natural resources necessary for America’s well-being already existed in abundance. So did the enlightened principles necessary for “the unbounded extension of Commerce.” To establish conditions conducive for natural growth, though, political leaders needed to adhere to four principles: a government “under one Federal Head,” a “Sacred regard to Public Justice,” a military “Peace Establishment,” and a spirit of national unity in which individuals would “make those mutual concessions which are requisite to the general prosperity.”17

Economic considerations underpinned all of these principles. It was only in a unified government, Washington wrote, that “our Independence is acknowledged, that our power can be regarded, or our Credit supported among Foreign Nations.” Public justice meant above all that the states rendered “compleat justice to all the Public Creditors.” All debts domestic and foreign, he insisted, must be scrupulously honored—including those to the men of the army. The alternative was “a National Bankruptcy, with all its deplorable consequences.” The military stood as “the Palladium of our security” under which free commerce could thrive. Finally, in advocating an undivided public spirit in which individuals would make sacrifices for the “interest of the Community,” Washington enshrined the principle of limited taxation, necessary not just for the survival of the government but for the public welfare.18

Washington’s understanding of the economic underpinnings of the war effort had informed his military leadership. As commander in chief he had set an example of probity and thrift, and by his intelligence, hard work, and ability to identify effective deputies he had ensured that the army ran efficiently. Washington’s diligence in this regard probably saved the country many millions of dollars. And while he could not solve the country’s economic problems, he did help to alleviate them. He did so in part by advising and consulting with Congress, and partly by working—if only symbolically—at critical moments such as Trenton to restore confidence and shore up public credit.

The community of commerce that Washington built between army and civilians simultaneously helped to unify American society and rebuff British efforts to undermine the war effort. Most important, Washington’s sense that the true threat to American independence was not external military pressure but internal collapse led him to conduct military operations in a way that ensured that a functioning civil society would emerge from the war. Much work remained to be done if the plant of national prosperity was to grow. Nothing would have been possible, though, had Washington not helped to sow and lovingly nurture the seed.