With the continuing difficulty we had in raising funding, the idea of doing a Kickstarter campaign became more appealing. It was something that we had discussed over the previous six months but never actively pursued. It had always been a consideration, mostly in the back of our minds, to be used much like the fire alarm on the wall with the inscription “Pull Lever in Case of Emergency.” That time had arrived.

Up to this point, we all had been working under a lot of pressure to complete the basic design of the player. We reached a point in the development where we had built fifty prototypes for testing. It was the first time we had a “looks like, almost works like” product to hold in our hands. While it didn’t have Stuart’s software or the new electronic design that Charley Hansen was developing, it allowed us to test almost everything else. It was a major milestone, one of the most exciting times in the development of a new product, when you go from having a few rough prototypes to dozens of identical-looking units that are close to the finished product.

No one was more excited than Neil to get one in his hands. He used it day and night, and over the next few months became the most prolific of all those testing the player. He’d find all the issues and bugs before any of us and would suggest many improvements, particularly for the software and user interface. While sometimes it would be embarrassing that he found a bug first, we all were resigned to the fact that he was just better than any of us in discovering issues. It was the same characteristic we saw over and over in Neil, doing everything with a high degree of passion and being a perfectionist about whatever project he took on.

SERIOUS NEED FOR MONEY

Focusing on the players, however, masked our serious financial state. We had managed to survive with financing from Neil’s friends and many small investors who believed in Neil’s cause. But we all knew that now, to get any further and take Pono into production, we would require much more money.

Designing hardware products is an expensive process. The development costs are rarely predictable, with the need to design, test, and redesign many times over to get everything working correctly. But the largest expense is purchasing the parts needed to build production quantities of the product well in advance of being able to sell them. The amount can be more than all the previous costs combined. This is the point that many startup companies reach, only to realize they need much more money than they anticipated. They’re suddenly surprised, unable to raise the needed funding to proceed, and often stall or even go out of business. It’s also the time when companies examine their product and sometimes cancel it if the market has changed and their product is no longer competitive. It’s the point of no return because these costs can typically reach a few million dollars. We were fast approaching this critical milestone as the new design was nearing completion.

With Stuart’s technology off the table and Hansen’s still an unproven alternative, there was too much doubt and uncertainty, at least among the large professional investors. Some still believed that no one cared about high-res music. Others believed streaming was replacing downloads and our approach was too little, too late. And some just didn’t want to invest in a company headed by a rock star. Neil was undeterred and did a couple of private concerts to bring in enough money to keep us going.

KICKING OFF KICKSTARTER

Kickstarter now looked like our best option. We debated how a Kickstarter campaign would affect Neil’s image. It was rare at the time for successful artists to appeal to the public to raise money, when the public’s perception was that artists could fund a project on their own—a perception not always consistent with reality.

Neil lived modestly, for the most part, but had huge expenses associated with supporting his family and his staff. The investments he kept putting into Pono were more to support the cause of music than to make a lot of money. He had much better ways to make money than working so hard on Pono. This was a labor of love. He kept pouring in money until his financial advisor told him, no more.

In January we decided to proceed with a Kickstarter campaign. In addition to providing us the money we needed to continue, we thought it would answer, once and for all, whether people really cared about high-quality audio. The professional investors we met with had dismissed the need for better audio and said no one cared anymore. Kickstarter could prove them wrong.

A Kickstarter campaign is simple in concept. It asks individuals to pledge a dollar amount in return for the expectation of receiving a reward—in our case, a Pono music player. Technically, it’s not a purchase but a donation. The donor hopes they’ll get what was offered, but there’s no assurance that they’ll get anything. There’s no recourse and no refunds, because they’ve not bought anything. If the campaign fails to reach its goal, then the money is returned. That encourages companies not to set too high of a goal, but it also means some companies make their goal but don’t have enough money to fulfill their commitments.

If a campaign reaches its goal after concluding, the company receives a lump sum payment, minus a commission to Kickstarter and payment processing fees to Amazon, together totaling about 10 percent of the gross.

At the time, in early 2014, few Kickstarter campaigns had raised large amounts of money. The biggest success had been the Pebble Watch, a watch connected to a phone that was the precursor to the Apple Watch and that raised more than $10 million—an astonishing amount. Most Kickstarter campaigns brought in anywhere from tens of thousands of dollars to, in rare cases, a few hundred thousand.

While many of us kept analyzing and discussing whether we should do Kickstarter, Neil was the most comfortable with just going forward and doing it. As was his nature, Neil often came to his conclusions based on intuition and instinct, doing what was best for his fans, fellow musicians, and music itself. While many of us were worried about his reputation as a result of doing Kickstarter, that was never an issue with Neil. When he believed in something, he pushed forward and never seemed to worry how others judged him. If something didn’t work, there was always plan B. He rarely looked back to express regrets.

Because the project was backed by Neil Young, we got the attention of Kickstarter’s cofounder Yancey Strickler, who encouraged us to move forward but counseled us to ask for less than a million dollars, explaining that a celebrity asking for so much money might result in a backlash that would hurt the campaign and tarnish the celebrity’s reputation.

Kickstarter recommends that campaigns begin before the product is completed, but usually within six to nine months of when it’s expected to be done. That adds to the excitement and creates more interest around the campaign. At the time of our offering, fewer than a quarter of the campaigns that were funded were successful as measured by the donor receiving what they pledged for, and many of those that were successful took years longer than promised.

In addition to getting the needed cash, Kickstarter can help measure interest in a product—still a big question we had. While we all cared deeply and believed our mission was important to music and the artists, how did others feel? While not scientific, a good showing on Kickstarter would confirm interest and might encourage others to invest. The big fear of those doing Kickstarter campaigns is to not reach their goal and, consequently, having to return the contributions, facing the disappointment of not enough interest, and even closing down.

Our Kickstarter campaign promise was to deliver a Pono music player, which still was being designed. We didn’t know how long that would take or how much the final product would cost. We didn’t even know whether Charley’s new design would fit into the case or how well it would work; we only had the promise from Hansen that he could do something that would sound great. That didn’t stop us from showing our current test models on our Kickstarter website. The fact that we were able to show many details gave us credibility that we were real and had a good chance of doing what we said we could.

To help us design and promote the Kickstarter campaign, we enlisted Alex Daly, a Brooklyn-based consultant who had run several successful Kickstarter campaigns and who a few years later become known as the “Crowdsourceress” after publishing a book by that name. Her task was to develop enticing content for the Kickstarter site and define all of the rewards and merchandise that we’d be offering. The campaign would run for about forty days, considered by Daly to be an ideal time to maximize donations without becoming stale. It would begin on March 11, 2014, the same day Neil was scheduled to deliver a keynote address at South by Southwest (SXSW), the annual music and entertainment conference in Austin, Texas.

Our internal goal was to raise $1.5 million, a number that seemed ambitious but was the minimum we’d need to complete the design and begin manufacturing. It was certainly not anywhere near enough to fund all of our manufacturing needs, but it was enough to keep us going while the search for serious funding continued. Following Strickler’s advice, we set the goal at $800,000—low enough to reach, but half of what we thought we’d need.

We had very little time between when we decided to crowdfund, in January, and the campaign launch, in March. The plan was for Neil to meet with the press covering SXSW the day after the Kickstarter began and to provide the first demo of Pono with the latest design, assuming Hansen was able to complete his prototype in time. That would help create more awareness of the campaign and improve our chances of reaching our goal.

Hansen and his engineers were hard at work on their design in Boulder and agreed to try to have their first demo in time for this SXSW press briefing. The prototype that would be shown would look nothing like a Pono, because it was all built by hand, months away from designing the circuit board that would hopefully fit. It would be several circuit boards with a jumble of wires, switches, and components.

The rewards we’d offer to Kickstarter supporters for their donations would be Pono players, as well as signed posters, shirts, and tickets to several group dinners with Neil. Early supporters would get the best deals on the players, and others would be enticed to jump in as they saw the early offerings being gobbled up, with the remaining players going for successively higher prices.

COST AND TIME?

As part of the preparation for the Kickstarter campaign, I needed to provide a delivery date and pricing for the players offered. Ship dates are notoriously hard to predict at this stage because of the uncertainty about the problems that lie ahead. The product cost would depend on the final parts being used (called the bill of materials, or BOM), the manufacturer’s costs to manage and assemble it, and their profit. All of these costs depended on how many units we would build. We were months away from knowing any of these details with much certainty.

I had to come up with numbers to use; a date and price that would be attractive enough for supporters, but not so far-out or expensive that the campaign might fail. After considerable head-scratching, I estimated that we’d be able to start delivering the product in about seven months, in October. I estimated the cost, based on the parts we used for the first design, and assumed the new design would not add very much more. The other uncertainties were the manufacturer’s assembly cost and margin and the volume we’d build. I decided to use an estimate of $175 as our cost for the player. That was based on about $140 in material costs at the time and a belief we could make inroads in that cost with higher volumes. That turned out to be fairly accurate.

To be able to offer a variety of Pono models on Kickstarter with different prices to entice early pledges, we offered the player in two colors, yellow and black, with the first 100 units of each color being sold for $199, and successive units at $299, compared to a suggested retail price of $399. The $399 was determined by what we considered the maximum selling price should be. While that limited our margin if the cost was really $175, I was confident the cost would be lower as the volume grew, but that anything greater than $399 retail would seriously restrict sales. We all thought $299 was a much more attractive retail price but decided to settle on $399. Even that price would make it difficult to sell at retail and still provide much profitability.

ARTISTS’ EDITIONS

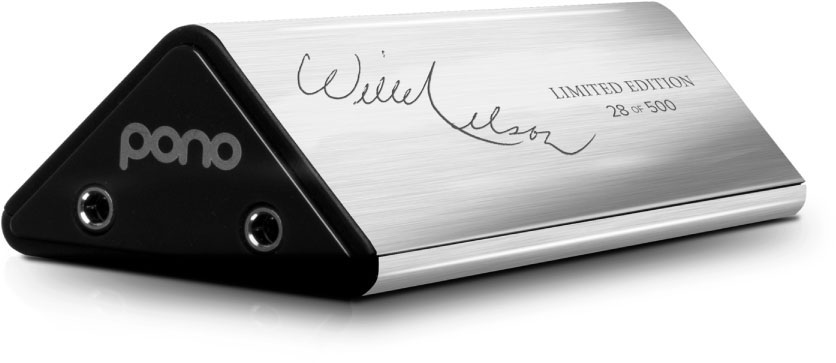

Shortly before the Kickstarter campaign was to begin, Neil called me and asked if we could make some special artists’ editions of the players in chrome in addition to the yellow and black ones. Neil and Elliot had been talking with other artists and their managers, asking for their participation in the campaign, since Pono was, in fact, an artists’ movement and many of them were early investors. Elliot told me that we got the go-ahead to create limited-edition players representing thirty different artists/groups supporting Pono: Pearl Jam, Metallica, Crosby, Stills & Nash, Tom Petty, Foo Fighters, Patti Smith, James Taylor, Herbie Hancock, Red Hot Chili Peppers, Norah Jones, Beck, Willie Nelson, Dave Matthews, Arcade Fire, The Grateful Dead, The Eagles, Buffalo Springfield, Jackson Browne, Lenny Kravitz, Elton John, Mumford and Sons, My Morning Jacket, ZZ Top, Tegan and Sara, Lyle Lovett, Emmylou Harris, Kings of Leon, Kenny Rogers, Neil Young with Crazy Horse, and Portugal. The Man.

And of course, there was a Neil Young edition.

There would be 500 serialized units for each artist with their names and signatures engraved on the players, and one of their albums preloaded, all in a special package that included a leather case. They would sell for $100 more, at $400, and they’d never be available again once the campaign was over.

The enclosures on the standard players were molded plastic with a rubberized, soft-touch paint finish. The challenge for the special-edition products was to be able to plate the plastic parts to look like metal and find a way to etch the artists’ names on them.

It was another example of Neil’s creative thinking to come up with new ideas, even if it was at the last minute. Of course, we can make them, I answered, wondering to myself, Just how? Somehow, I’d find a way. That night I emailed John Garvey, the head of engineering at our manufacturer, PCH, in China, and explained what Neil wanted. By the time I woke up the next morning, he had emailed me that it could be done, and I’d have samples a few days later. This kind of can-do response is one of the benefits of manufacturing in China. It’s never a month, rarely a week, and usually a day or two to get answers. They just work on a much more compressed time scale than their US counterparts.

Franz Krachtus, a graphic designer and friend I had brought on to help, created Photoshop images of the various versions of the players for the Kickstarter site. I asked him to make images of chrome-finished limited-edition players with artists’ signatures. A few hours later, he sent me the files and they looked just like the real product.

Building the Kickstarter website involved lots of work in order for us to tell the story. It used video, still images, and dialogue. Since Neil had told the story so often, the messaging would be clear: it was about saving the music and bringing music fans an easy way to buy and listen to the world’s finest recordings. The highlight of the site was the video of Neil demoing the player to dozens of his artist and music executive friends riding in his car and experiencing their reactions in real time.

The Kickstarter site went live at noon Austin time on March 15, four hours before Neil began his keynote speech. Neil posted this message to his artist friends:

First, we say thanks to all of you artists who have been here with Pono since the beginning. We are deeply grateful for your encouragement and support.

When you and your recording team go into a studio or recording environment to create your latest music, there are many choices for you to make. Besides the studios, songs, players, singers, producers, engineers, microphones, and other equipment, you have the ability to choose from the numerous digital resolutions at your disposal to capture your sound. This is where Pono can make a giant difference.

You no longer have to be satisfied with MP3 or CD being what your fans hear. Pono plays back anything you can create, just as you made it, in the digital domain.

If you are an artist who has been recording for years and this has been your life and always will be, your original creations in analog can be transferred to the highest quality digital and heard anew with Pono. No longer do your original recordings have to be the compressed sound of CDs and MP3s.

If you are a new artist, always released on MP3s and CDs, then your horizon has just been radically expanded. You can now record in whatever resolution you choose, and your fans will hear the same quality you heard in the studio. You no longer have to lose part of your sound when it goes to the people. You are no longer limited by a format. Now your audience can hear what you hear.

The Pono music player can bring new light to all of your creations through Pono Music.

Record companies, this is an opportunity to rescue the art of recorded sound. Why should a Frank Sinatra recording or an Adele recording or a Nirvana, Rolling Stones, Beatles, Led Zeppelin, Who, or classical recording be limited to the CD format for the future? This music is world cultural history. All of this cultural history should be preserved for enjoyment of the people in its highest possible form forever. In the twenty-first century, people, and art, deserve this technology. Bring it on. Now, as never before, it is possible.

Our listeners should hear what we heard.

Thanks for listening,

Neil Young

This message was posted on Kickstarter to potential donors:

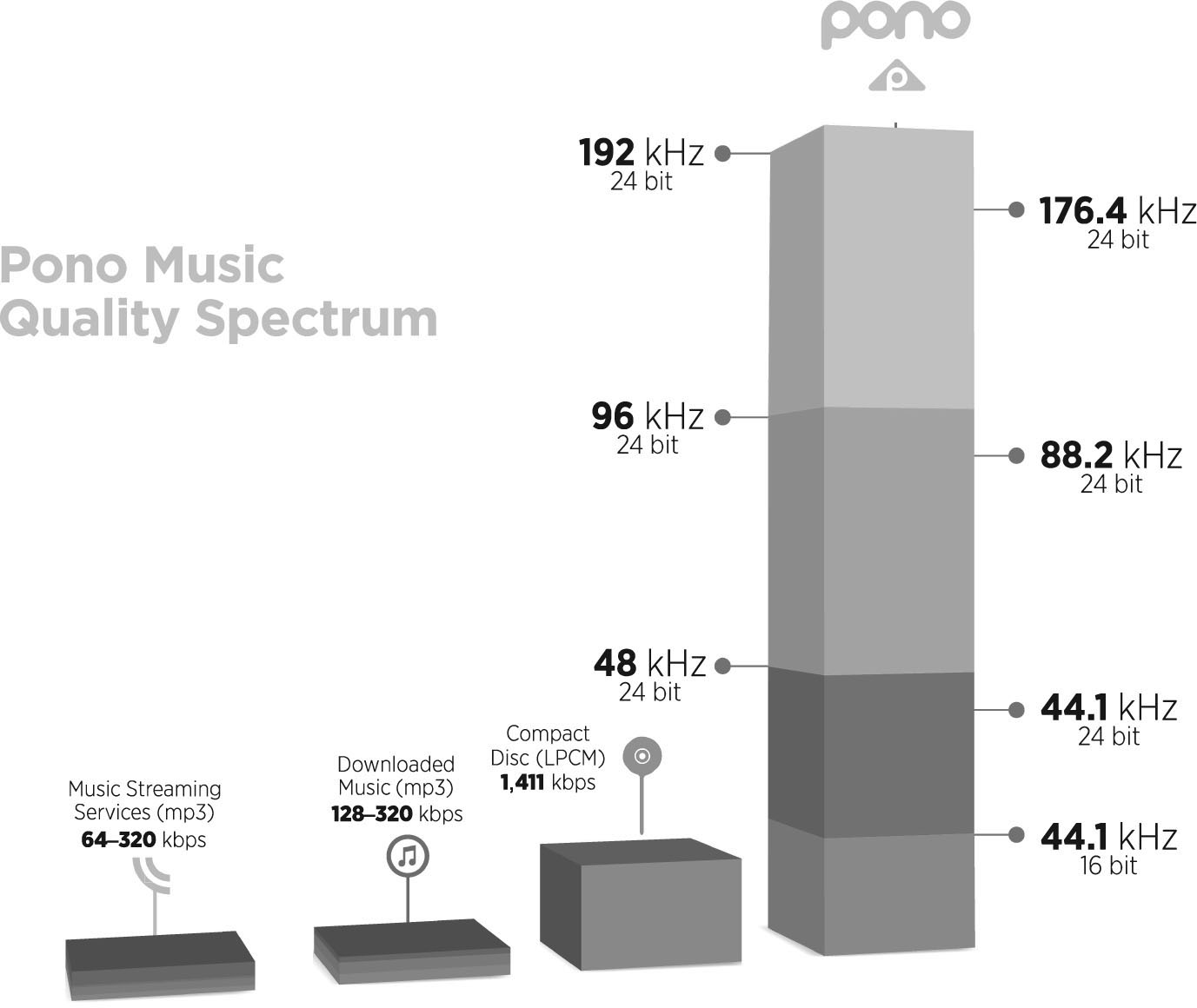

How Pono quality was explained on Kickstarter

What is Pono Music?

“Pono” is Hawaiian for righteous. What righteous means to our founder Neil Young is honoring the artist’s intention and the soul of music. That’s why he’s been on a quest, for a few years now, to revive the magic that has been squeezed out of digital music. In the process of making music more convenient—easier to download and more portable—we have sacrificed the emotional impact that only higher quality music can deliver. However, the world has changed in the last ten years—technology has solved some of the underlying problems that forced that tradeoff. You no longer have to choose between quality and convenience when listening to music—you can have both. This is the fundamental idea behind Pono Music.

Pono’s mission is to provide the best possible listening experience of your favorite music.

We are pursuing this vision by building a system for the entire music listening experience—from the original master recordings to the PonoMusic.com store to the portable Pono Player. So now you’ll hear the nuances, the soft touches, and the ends on the echo—the texture and the emotion of the music the artist worked so hard to create.

Thanks for listening,

Neil Young

KICKSTARTER KICKOFF

Once the Kickstarter campaign began, it didn’t take long to go from worrying if we’d ever hit $800,000 to being overwhelmed with excitement and enthusiasm. From pessimism to optimism, from planning our demise to being able to accomplish our mission; all those emotions occurred over a short twenty-four-hour time span as the money poured in. By the time Neil finished his talk at SXSW at about 5 pm, just a few hours after the campaign went live, we had reached $500,000. Over dinner a few hours later at a local restaurant, I sat next to Neil, quickly graphing the totals as a function of time on a napkin. (I later learned there was an app for that.) It showed an increase of about $100,000 each hour.

Our initial hesitation that we might not hit our minimum disappeared minutes after the campaign had begun. From the response, it seemed that there really might be an untapped market for high-quality music. At least that was what we believed at the time.

Our excitement and giddiness were suddenly interrupted the next morning with a surprise. Bob Stuart contacted our lawyer, Rick Cohen, and said we were disclosing confidential information on our Kickstarter website. He was referring to an image of the inside of the Pono player that showed the prototype circuit board, including the programmable memory chip that was to store his software—the software that hadn’t arrived.

I thought his complaint was unfounded because there was nothing that was proprietary in the image that would indicate anything related to his technology, and nothing that he designed. In fact, his backing out of our arrangement required us to design around the chip in order to get our early prototypes to work. The chips simply just sat on the boards unused.

But Cohen requested that we remove the images from our Kickstarter website right away. I called Franz and he quickly edited out the chip from the image.

To my astonishment, Cohen then asked that I recall all fifty prototypes that were in the hands of our employees, board members, and beta testers and destroy them! These prototypes cost us many thousands of dollars and were needed for testing and development work. That made no sense to me and I explained that it would seriously affect our ability to continue development and testing. I called Neil and Elliot, who advised me to follow Cohen’s advice, but agreed to allow Dave Gallatin and Dave Paulsen to hold on to their players and keep working on the design. (Cohen declined an interview for this book.)

Stuart’s call cast a momentary pall over the campaign, with all of us fearful that he might try to interfere with it, perhaps even try to shut it down. Some of us surmised that Stuart might have been upset that we were using audio technology from Charley Hansen and Ayre Acoustics, a competitor. This was all so ironic, since Stuart still owned a sizable chunk of Pono. Fortunately, that was the last we heard from him about our Kickstarter campaign.

Money continued to pour in. First, we hoped to hit $2 million, then $3 million. At the end of the campaign, 18,220 individuals contributed, including 17,159 who pledged $200 to $400 for the music players. We raised a total of $6.2 million—at the time, Kickstarter’s second-highest-grossing hardware campaign and third largest among all categories.

Rolling Stone magazine described the results:

The campaign closed out at over $6 million on April 15th with full backing on several pledges tied to rewards, including signature series Ponos bearing pre-loaded music and autograph inscriptions by Metallica, Tom Petty, Pearl Jam and, of course, Young. Two of the rewards for the top-priced $5,000 pledge levels—dinner and VIP listening parties with Young in California and New York City—also sold out. In total, 18,220 people backed the campaign, pledging $6,225,354. Kickstarter’s rules say that project organizers can keep money raised above and beyond the initial funding threshold.7

We were all elated. We proved there was interest, and we had the funding to finish developing the music store and player and begin manufacturing.

KICKSTARTER PLAYER BACKERS BY COUNTRY

Country |

No. of Backers |

United States |

8,582 |

Canada |

1,312 |

United Kingdom |

1,054 |

Australia |

685 |

Germany |

622 |

Japan |

617 |

Netherlands |

343 |

France |

317 |

Switzerland |

249 |

Sweden |

193 |

Italy |

180 |

Norway |

173 |

Spain |

161 |

Belgium |

150 |

New Zealand |

133 |

Denmark |

122 |

Singapore |

94 |

Hong Kong |

81 |

Ireland |

80 |

Brazil |

75 |

Austria |

63 |

Czech Republic |

62 |

Mexico |

61 |

Finland |

58 |

Israel |

46 |

Russian Federation |

33 |

Taiwan |

27 |

China |

24 |

Chile |

20 |

United Arab Emirates |

20 |

South Africa |

20 |

Portugal |

19 |

Malaysia |

18 |

Thailand |

16 |

Poland |

16 |

India |

15 |

Greece |

11 |

Luxembourg |

11 |

Korea, Republic of |

11 |

Hungary |

9 |

Indonesia |

8 |

Iceland |

4 |

Brunei Darussalam |

4 |

Philippines |

4 |

Peru |

4 |

Latvia |

4 |

Jersey |

3 |

Turkey |

3 |

Malta |

3 |

Slovenia |

3 |

Croatia |

3 |

Belarus |

3 |

Ukraine |

3 |

Lithuania |

2 |

Cyprus |

2 |

Cayman Islands |

2 |

Macao |

2 |

Argentina |

2 |

Oman |

2 |

Bulgaria |

2 |

Qatar |

2 |

Bermuda |

2 |

Romania |

2 |

Vietnam |

2 |

Bahrain |

2 |

Estonia |

2 |

Maldives |

1 |

Costa Rica |

1 |

New Caledonia |

1 |

Pakistan |

1 |

Uruguay |

1 |

Mauritius |

1 |

Guadeloupe |

1 |

Greenland |

1 |

Colombia |

1 |

French Polynesia |

1 |

Saudi Arabia |

1 |

Kuwait |

1 |

Azerbaijan |

1 |

Moldova, Republic of |

1 |

Lebanon |

1 |

Grand Total |

15,876 |

![]()

7 Kory Grow, “Neil Young’s Pono Kickstarter Raises Over $6 Million,” Rolling Stone, April 15, 2014, https://www.rollingstone.com/music/music-news/neil-youngs-pono-kickstarter-raises-over-6-million-189401/.