ADDING PAINT

If one says ‘Red’ – the name of the colour – and there are fifty people listening, it can be expected that there will be fifty reds in their minds. And one can be sure that all these reds will be very different.

Josef Albers

Colour is crucial in painting, but it is very hard to talk about. There is almost nothing you can say that holds up as a generalization, because it depends on too many factors: size, modulation, the rest of the field, a certain consistency that colour has with forms, and the statement you’re trying to make.

Roy Lichtenstein

I want to know one thing. What is colour?

Pablo Picasso

Colour, and its application, is a highly subjective area. The approach will vary from person to person and we all see and interpret colour in our own way. The use of colour is also associated with a personal painting style, and with the artist’s philosophical approach to making images. Certain techniques demand particular consistencies of paint, and environmental conditions will have a bearing on the pigments and suspensions.

Andrew Ellis: Roller.

The options are wide indeed and there are many instructive publications for the interested student to research. Firstly, however, you should be aware of the ‘colour wheel’, and what are primary, secondary and complementary colours. A colour wheel has six segments. In three, spaced evenly apart, are the primary colours (red, blue and yellow). Interspaced are the colours that are made when the flanking primaries are mixed. Between red and yellow is orange, between yellow and blue is green and between blue and red is purple. These are the secondary colours. In the six-segment wheel the colours opposite each other are called the complementary colours: red and green, blue and orange, and yellow and purple. When complementary colours are laid beside each other, they can make interesting combinations and each serves to emphasize the qualities of the other. When a complementary colour is applied over its opposite (or mixed with it), the effect is to subdue the vibrancy. There is much theory regarding colour; however, regarding the painting of birds it may be informative to follow a process through as in a real-life situation.

Nick Derry: green woodpecker. Watercolour, acrylics and collage.

Texture is closely allied to colour and notes on surface quality and feel will add to the richness of recollection when you come to revisit the original drawings.

ADDING COLOUR IN THE FIELD

The addition of colour to your drawings is a brave stride forward.

When drawing outside, written notes about local colour can help to break down the psychological barrier of actually painting in the field. The making of a list and a written description helps you to analyse what colours you are in fact seeing and additional observations such as ‘grades from pale purple to dark blue’ and a directional arrow can be interpreted when you come to address the collected sketches back in the studio. Try to use your own descriptions for how a scene looks – reference to food or emotions when describing colour can be very useful when you come to the process of painting. Before long, however, you’ll get the paints out and place a bit of colour on the paper.

In the first instance it should be kept as simple as possible, perhaps exchanging the grey values of the pencil marks for blue hues of shadow.

Take a sketch and lay a light shade of blue along the underside (use coloured pencils or a wash of watercolour) and see how the volume of the drawing is accentuated.

Highlighted areas in drawings can accept a pale yellow wash of colour to emphasize the strength of light bathing the image.

Tim Wootton: mallard duck. Early afternoon is a good time to draw birds if you’re after amenable subjects, as many birds will be thinking about having a mid-day rest, preen and stretch and maybe have a doze. This female mallard had just gone through such a routine and was now standing on a mid-water rock. I made a quick outline sketch in preparation for paint. Stage 1: paint an overall brown wash (raw umber); Stage 2: lay a darkish hue (purple) under the bird’s belly and on the top of its breast, leaving an area in the middle which is reflecting a lot of light; Stage 3: paint a warmer brown (burnt sienna) still leaving the light area; Stage 4: add a few markings in raw umber mixed with a touch of blue; Stage 5: darken the shadow, add colour to the bill and sketch a general tone behind the bird to give it background.

Paschalis Dougalis: male shoveler in eclipse plumage. Lights and darks and a subtle use of browns over a very precise pencil study made from a tame bird.

Tim Wootton: wigeon group. Blobs of colour quickly applied over thumbnail sketches – an account of the scene.

Taking it a step further: on page 95 is a demonstration of how I quickly place a touch of colour on a drawing whilst looking at the subject. This piece was drawn from a distant bird through a telescope from the relative comfort of a bird hide – an excellent place to paint as it has a shelf for sketchbooks, paints and water (although some may feel reluctant to draw in front of other people). A car can always double as a hide but is a little more cramped and the angle of view can give you a crick in the neck. The boot of an estate car can be surprisingly comfortable if you can manoeuvre it so the back is pointing towards the subject and set the scope up on the ground; all your drawing materials can be in easy reach and you and your artwork will receive some protection from the weather.

John Busby: house martins collecting mud. These are drawn as he sees them with a smear of blue and grey to lift the birds’ upper parts and a diluted hue suggesting shadow under the elevated wings.

John Threlfall: incubating fulmar. Field painting; the colours in shade are quite muted and washed with greyish blue, as are the shadow areas of the bird.

If there is strong light there will be strong shadow, or at least it will be apparent which areas are in the shade. A quick and effective way to describe this is to try and see the point at which the light stops hitting the bird and draw the boundary with a line. A wash of blue into this zone will quickly depict the shadow areas. There will also be subtle areas of shadow within the highlighted areas and areas of relative illumination within the shade.

Tim Wootton: eiders on the Peedie Pier. Field painting. These two colour sketches are of birds in strong direct light, influenced by reflected light from their immediate surroundings. Selecting compliant models such as incubating seabirds or loafing wildfowl gives the artist the opportunity to consider colour as well as the form of the subject and its environs. The aspect of the immediate landscape is important because only when the bird is put into its surroundings can it be understood in context.

Paschalis Dougalis: incubating coot. The artist has seized an ideal opportunity to explore the subtleties of hue, value and texture in the bird’s plumage. The floating nest of branches and dead vegetation is rendered as thoughtfully as the bird, giving the sketch a very wholesome flavour.

Tim Wootton: grey herons. Felt tip and watercolour drawn from the car using a telescope.

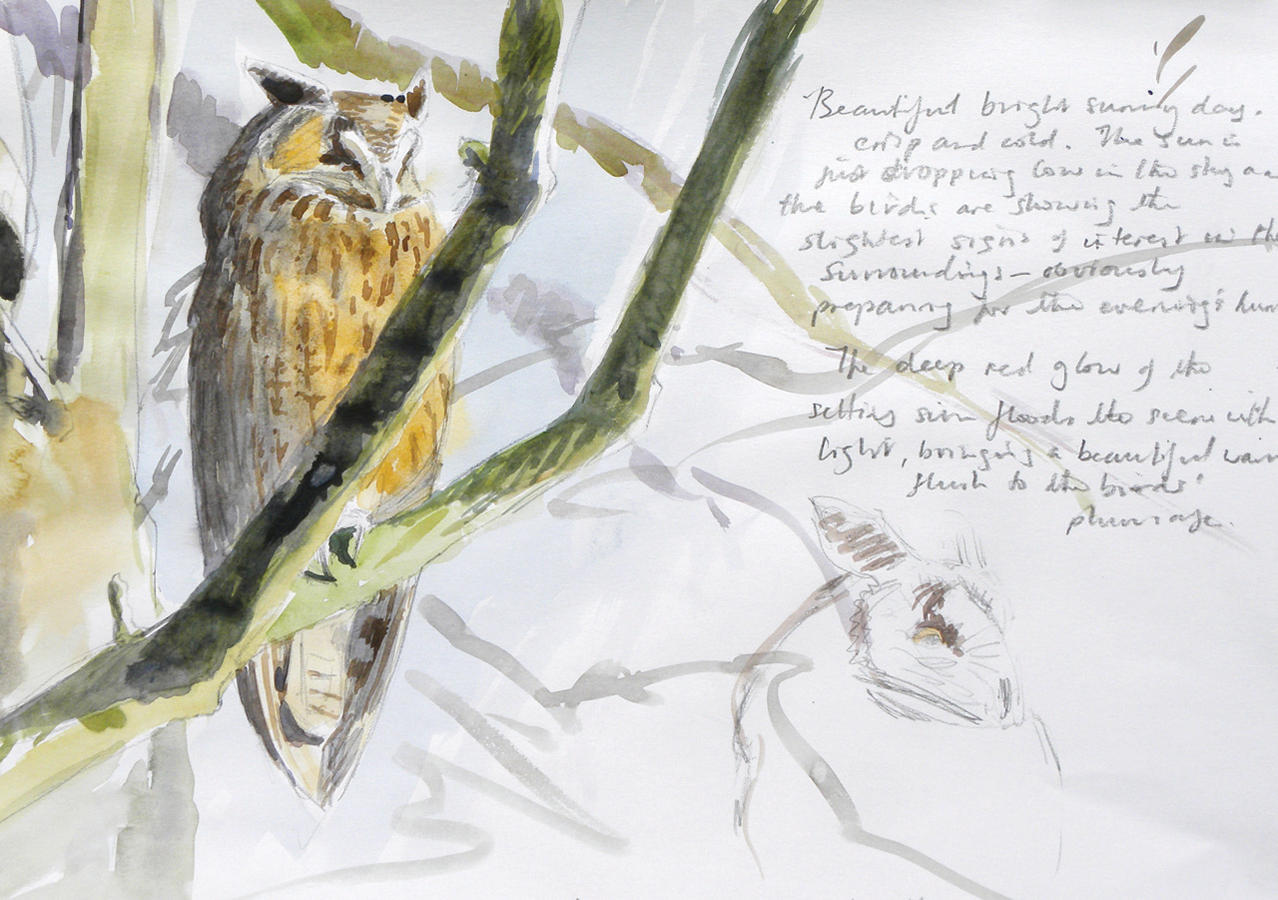

Tim Wootton: study of a long-eared owl. This is a drawing of one of two birds that had been using a stand of gnarled sycamore trees as a winter daytime roost for a number of weeks. It was apparent that they were very settled and unlikely to flee the scene so I took a little more time drawing detail than is usual for me in the field. The low winter sun bathed the scene in golden light, accentuating the warm hues in the bird’s plumage. The addition of the sketch of the tree is essential to place the bird in context as is the play of light and shade. There are three colours used in the sketch (in addition to the graphite drawing): burnt sienna, sap green and violet, mixed in different proportions and applied wet in places and more intensely within the darker areas. The study was painted whilst watching the bird through a telescope.

Darren Woodhead: peregrine food pass (watercolour). Using a very minimal palette of burnt sienna and Prussian blue the artist recreates this fascinating piece of behaviour in a very pure watercolour technique.

Colour in nature is always changing depending on the intensity and amount of light and the direction from which the light is coming. A hawthorn tree in a grassy field will look similar in colour and density to the grass if the sun is behind you, but walk around the other side of the tree and, being in shade, it now looks almost black, whereas the light will be reflecting off the grass and lightening the value and the hue. So actually seeing colour in nature is almost an intuitive thing and deciding what colour relates to the tubes in your kit can be very difficult to work out. One approach is to try and evaluate the relative temperatures of the colours you’re seeing: a blue-green is a cool green; a green with hints of burnt sienna is a warm green; but often it’s not easy to make these judgements until you’ve physically placed some colour on the paper. Likewise when painting a bird there will be the overall plumage colour, the effect of light on the upper parts, and often the undersides and shaded areas will be picking up reflected hues from the local environment.

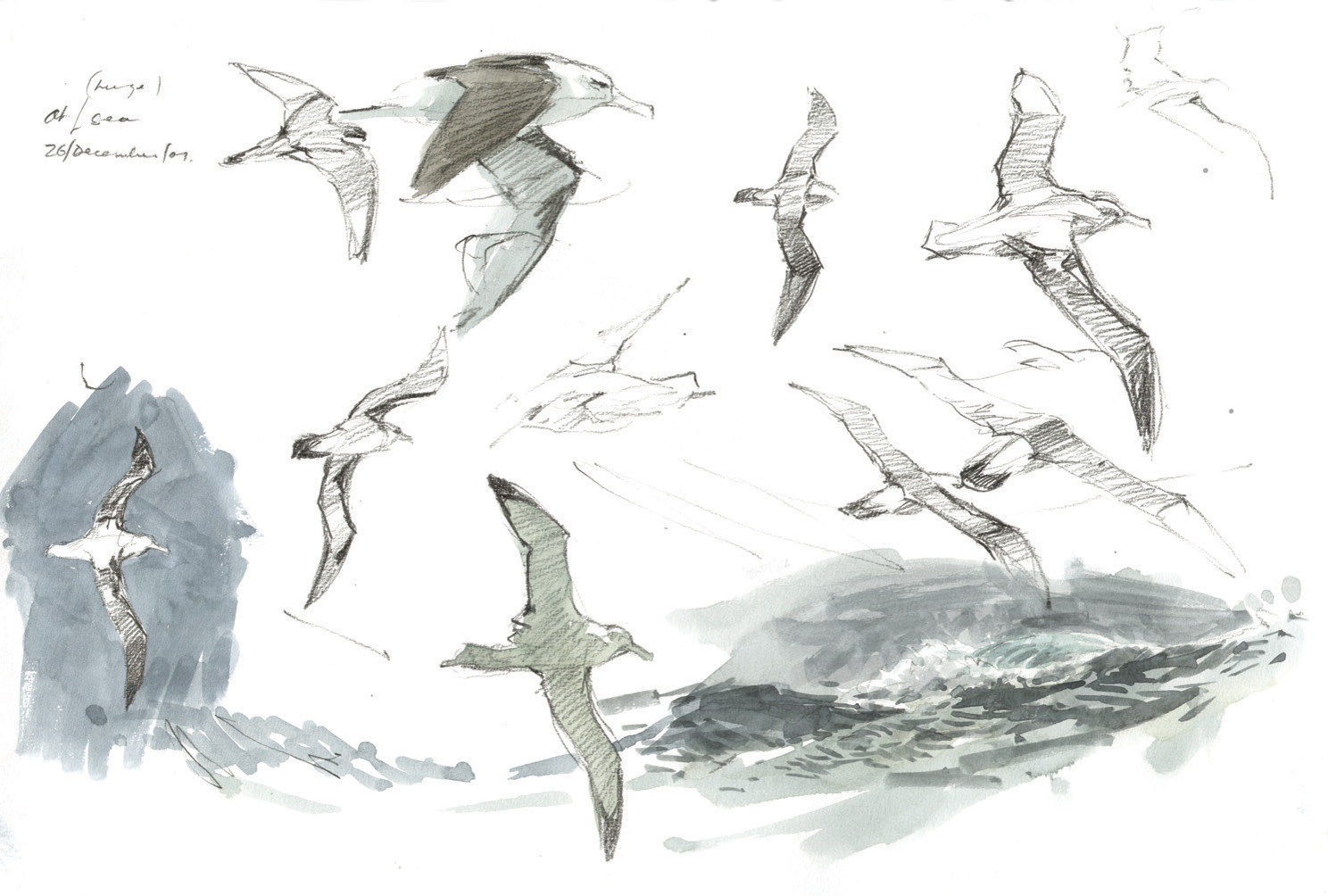

Bruce Pearson: field painting of albatrosses in the Southern Ocean (graphite and watercolour). Painted from the deck of a ship, the suggestion of light glaring from the surface of the sea is created by leaving much white paper showing through fairly transparent colours. The white underside of the lower bird is cast in shadow and set against the brightness of the reflected light; hence the artist places the bird relatively darker than its locale. The brooding sky is deckled with rain spots.

Bruce Pearson: flight studies of albatrosses. Graphite and watercolour wash. Investigative studies of form and light.

Be prepared! You never know when a wonderful opportunity to draw and paint may occur. Always have to hand a basic kit, which you can pop in a pocket or a handbag, glove box in the car or wherever. And for working in the field the kit could consist of a small watercolour field-box and a pencil case containing your preferred sketching pencils, a couple of watercolour brushes (with bristle protectors on), a pencil sharpener, biro and felt-tip pen. A small screw-top jar (the ones that have individual portions of jam or marmalade) containing water is very handy, as is a small selection of coloured pencils, which could feasibly be carried in your pencil case. A small tube of white gouache could also come in handy for obliterating errors in drawing (note: no rubber) and for mixing with watercolour to make a ‘body colour’ useful for stronger statements in colour or value.

Watercolour is the principal medium for field-sketching birds. Watercolour comes in tubes and as moist blocks called pans or, more often, half-pans. If you prefer tubes you will also need a palette (usually plastic or porcelain), whereas if you use half-pans they are available in compact boxes with integrated palettes. Both tubes and pans are used with the addition of water; colours are mixed on the palette. The colour is applied using conventional watercolour brushes or recently developed ‘reservoir’ brushes. The handles of these are tubes containing water – when they are squeezed, water irrigates through the bristles, thus negating the requirement of a separate water container.

Watercolour is a versatile medium but when used in direct sunshine it can dry exceptionally quickly. Conversely I have from time to time been working in the field when the water has frozen in the palette and on the bristles.

Watercolour pencils are worth trying. They are a convenient way to add tints; by drawing on paper interesting granular lines can be made and if water is added you can mix and wash colours on the paper. Heavier weight paper is recommended for this medium. Combining watercolour pencils and pure watercolour can give rise to some very interesting effects. Ordinary coloured pencils are appealing if you aren’t used to working in colour in the field – sketching with colour pencils has a natural feel to it and is a recommended process as an introduction to outdoor colour.

The serious plein-air painter will probably consider a pochade box – a portable kit containing drawers and compartments with paints, brushes, pastels, a mobile studio almost. Some have extendable arms that perform as an easel.

Oils and acrylics can be used outside. Acrylic paint is a fastdrying medium which is diluted with water for wash effects and used straight from the tube when painting more impasto pieces. Acrylics can also dry too quickly in warm weather and a spray bottle with water is worth taking with you. Spray the canvas or board regularly to keep your applied paints workable for longer. Retarding agents are also available; these extend drying times.

Oil paints are another traditional medium for outside painting, mainly by landscape painters, but they can be used for any style. White spirits are required to clean brushes and also to dilute the paints. They are less affected by climactic conditions than the water-based media. Recently developed are ‘interactive paints’. These are water-based oil paints; that is, they can be diluted and cleaned in water, but have many of the desirable properties of traditional oils. These could possibly be more practical for the outdoor painter.

Felt-tip pens are instant to use but may be a little crude for many situations in the field. Try using non-waterproof ones and add water for unusual wash effects. Pastels, soft and oil, are also instant and offer different possibilities for the artist. Try various combinations for grasses, water, rocks, and so on.

Painting blocks are an excellent idea. These are sheets of watercolour paper, lightly glued along the edges to form a block, which has inherent rigidity and is comfortable to work on. Once the painting is completed, the top sheet is removed, leaving a fresh surface to work on. Sheets of thin canvas and canvas-textured paper are available in pads too; a good solution for the outdoor painter who wishes to use thicker media.

In theory you could take as many materials as you were able to carry, but this would probably only confuse you; keeping it simple is sound advice. I tend to use only four or five colours in the field: burnt sienna and cobalt (or ultramarine) offer warm and cool hues in various proportions; violet is handy for lively shadow areas; sap green is nearly always combined with burnt sienna or yellow ochre for vegetation, occasionally with blue in certain circumstances. Yellow ochre can imply areas of sunlight and a tube of titanium white gouache is well worth taking along as it combines well with watercolour, creating opaque effects, and can be used as a glaze to suggest soft overhead light on a bird’s back, or to convey wet surfaces.

ADDING COLOUR IN THE STUDIO

Working in the studio is a very different process from working in the field. But that’s not to say that it is in any way a less exhilarating or indeed frustrating way of working. In fact, having more time to contemplate the methods and procedure can inhibit the way you make marks, apply paint, etc. Some methods of working would obviously not transfer from the studio into the field: spray guns which require air compressors, flimsy masking film, collage on windswept moorlands, etching presses, woodcut blocks and large-scale canvas pieces could all be tricky to use in the field. The studio is the place to experiment with processes and techniques. That’s not to say that your field kit and the way you use it isn’t just as valid in the studio. But the studio is more than a place sheltered from the wind. It’s where you can develop ideas, test equipment, have the music on to alter the mood and have a welcome tea break when required.

Esther Tyson: study of a cock house sparrow in oils. A very considered and economical use of oil pigment. The artist recounts the experience:

There has been a lot of snow this year and the house sparrows have congregated in and around the hedgerow at the bottom of my garden.

Snug and warm in the living room with my binoculars and oils, I watch the comings and goings of these little creatures. Sitting and watching I mix colours. Using a limited pallette, I work over and again on small studies, getting to know the sparrow. One minute puffed up, the next, feathers flatten; they become a different bird altogether. Behaviour, shape and pattern all aid me in my exploration in paint.

The ideas that form whilst you’re in the field are crucial to what you produce in the studio; however, that doesn’t mean they have to remain pure and untouched once indoors. Often it will be drawings and notes from weeks, months or even years ago that suddenly emerge from the pile of sketchbooks and demand your attention. No doubt you will recall almost every mark you made at the time, but the feelings you have about the drawings will certainly have altered in some way. And it’s often this change in perspective that makes revisiting older work so exciting and invigorating.

Tim Wootton: a typical workspace. Sketchbooks and coloured drawings being worked into a finished piece.

Someone who has spent most of his thirty-year career working entirely in the field, Bruce Pearson, has this to say about his modus operandi (from In A New Light, Lavenham, 2003):

The starting point has to be the field experience as pure observation is the raw material – perhaps a few small sketches, a larger more considered drawing, or an ambitious painting which one hopes distils something of the day’s experience. A work straight from the field can sometimes be framed and exhibited as it is; what’s left is taken back to the studio to be viewed in a new light and the snatched ideas worked through in different mediums – relief printing (lino and woodcuts), monotype, silk-screen printing, or oil painting.

Over a period of almost thirty years working as an artist I have travelled widely in search of subjects from the Arctic and Antarctica, to Africa, much of Europe, and the Americas. However, most of my time these days is spent in my studio.

The obsessive urge to head off into the field at every opportunity is transferring itself into an equal desire to work in the studio; to draw much more on the imagination, memory and accumulated experiences lying around.

So the studio is a place for reflection and experimentation, a place where we make art. But it can be virtually anywhere – it’s more a state of mind, I suppose. When I was younger I used my parents’ kitchen table, then a spare bedroom, an old cowshed and then a conservatory, so don’t let the lack of a purpose-built space stop you from creating art. If you can make a space your own for any length of time, it will become your studio and it can revert to being a utility room or greenhouse afterwards.

The one thing a studio really needs is decent lighting, be it from an anglepoise lamp or north-facing floor-to-ceiling windows – you need to be able to see what you’re doing. The work surface could be a table or an easel, or work could be pinned to the wall. A drawing board on your knee could suffice for smallish pieces and table-top easels are useful little things.

From there on it’s up to you to decide what media to work in, or which process you think would best suit the specific idea you are juggling with. Techniques you may like to tackle (besides the painting methods we touched on earlier) could include collage, lino-cut, woodblock and monotype printing and etching. Painting over prints can be an interesting way of making images too. It’s worth getting a good art-media book that covers techniques and materials; it is a vast subject.

Having time to reflect and make measured decisions about your work may result in a slight loss of spontaneity, but the compensation is that you can do exactly what you what, in your own timescale. In the case of oil painting, where drying times can run into weeks, a certain kind of mind-set is required. Little wonder then that oil painters tend to have several pieces on the go at the same time, which in itself can lead to cross-fertilization of ideas from piece to piece.

Time in the studio means you can devote time to planning and composition: subjects we will be covering in detail in Chapter 7.

John Threlfall: bullfinch.

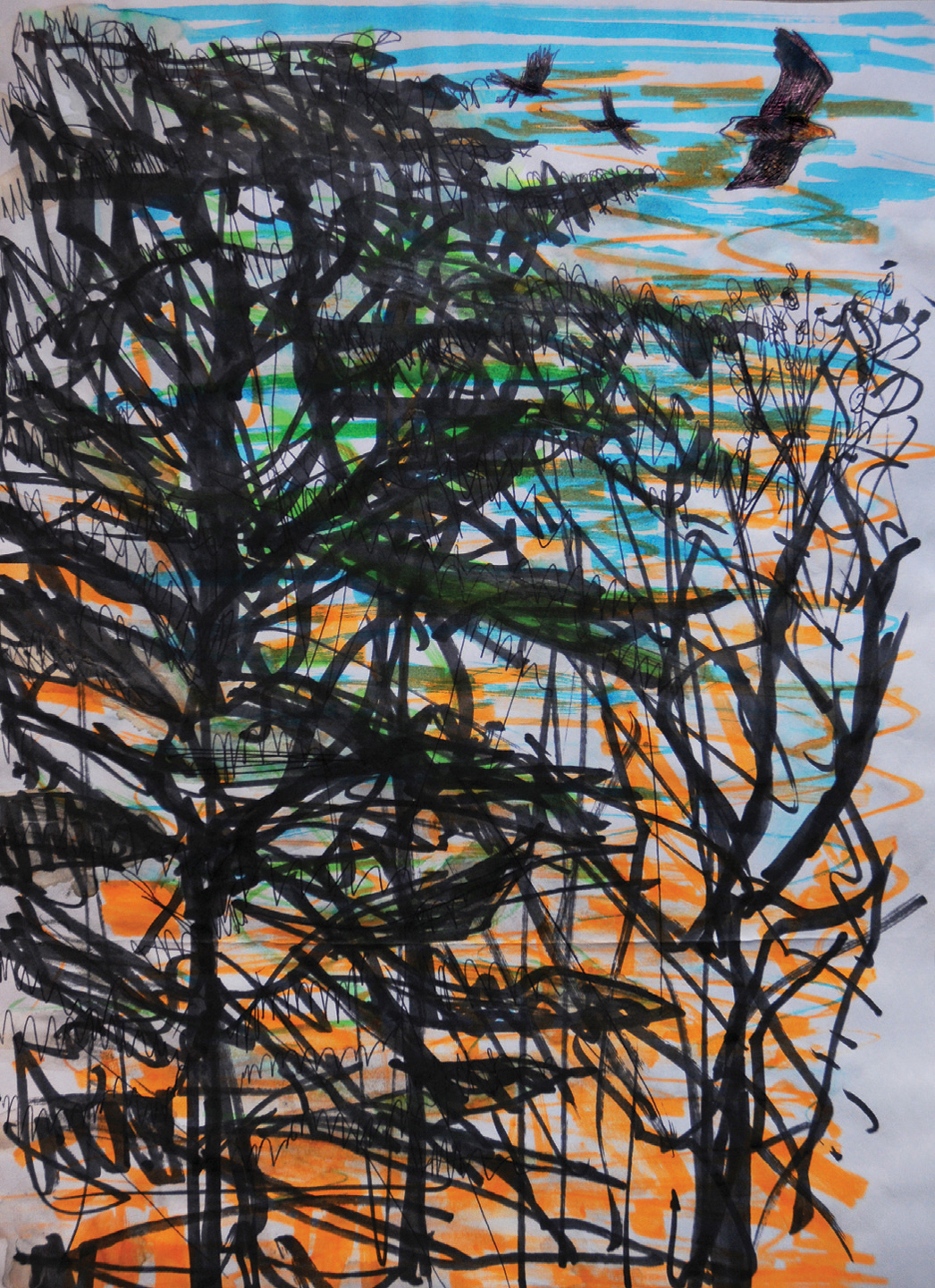

Ed Keeble: white-tailed eagle and crows. Felt tips and highlighter pen.

Paul Bartlett: preening egret. Collage and acrylic paint.

Tim Wootton: Force-seven Broadsides. Acrylic on canvas studio painting. Light and water form an irresistible combination; this painting is derived directly from seeing two fulmars on an afternoon dog-walk near my home. Although not late in the day, the northern winter sun was already low in the sky, a spicy 60-knot breeze was whipping spray from the caps of the rolling sea, and spume was collecting in banks along the high tide line. The fulmars just seemed to be enjoying it and I headed straight home, made a drawing in a sketchbook and over the next couple of days painted this piece.

Nick Derry: red-backed shrike. Acrylic on board.

THE SIBERIAN CRANE

Robert Bateman writes:

Imagine that the fate of your species depended upon some of the most densely populated, strife-torn, environmentally stressed and, in some cases, corrupt places in the world. That is where the future of the Siberian crane lies.

The western population is down to about ten birds; the central population has been reduced to two. The eastern population of approximately 2,500 birds is threatened by the Three Gorges Dam in China. These magnificent birds are the Asian equivalent of the whooping crane. With international efforts and of course financing, the good news story of the whooping cranes could be repeated. At one point their numbers were down to fourteen; now there are 300 to 350 birds.

I based this painting on one of the Siberians at the ICF. He is not preening; he is in a ‘sabre threat pose’. If you don’t get the hint, his next step is to jump you and either spear you with his beak or rake you with his claws. I was very taken by the abstract form in his defiant pose. I hope that in some small way it will help to get the attention of enough people to bring the Siberian crane back from its course towards extinction.

Robert Bateman: Defensive Stand – Siberian Crane. 36 × 36in. Acrylic on canvas, 1999.