CHAPTER ONE

EMBARCADERO

The land that became Sacramento was inhabited by the Nisenan (or Southern Maidu) for thousands of years. The town of Sa’cum’ne, or “Big Dance House,” was located near the original confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers, near the present-day site of Sacramento’s city hall. The Sacramento Valley was a highly ordered cultural landscape, managed by direct human intervention. The Nisenan’s deliberate use of fire and cultivation of important plants helped them to efficiently manage the bountiful but flood-prone plain, with defined areas of high ground used as retreats during winter months.2

The first nonnative visitor to the vicinity of K Street was probably New York–born mountain man Jedediah Smith. His 1826 trapping expedition from the Sacramento River to the site of Folsom prompted the Mexican government to name the river Smith’s party followed the Rio de los Americanos, or “American River.”3 A later trapping expedition by the Hudson Bay Company in 1833, led by John Work, introduced another foreign visitor—a virulent malaria epidemic that killed an estimated twenty thousand natives by the end of the year. This plague was devastating to the indigenous people of California, who had no resistance to the diseases introduced by Europeans. Due to this act of unintentional germ warfare, the formerly densely populated communities of the Sacramento Valley were still reeling from the effects when the first European settlers arrived. John Sutter, a Swiss trader seeking a land grant from the Mexican government, picked a defensible spot of high ground for his settlement a few miles east of the Sacramento River in 1839, near what is now the corner of Twenty-Seventh and K Streets.4

Sutter’s decision was not accidental. A decade of trapping expeditions coming south from Oregon Territory established the land near the confluence of the Sacramento and American Rivers as a trading site between Russian, French and American traders and the Nisenan. Farther south in the Sacramento River Delta were the Miwok, more hostile to European incursions and better equipped to resist them but welcoming of traders. Sutter approached them as a trader but did not settle in Miwok territory. The confluence of the two rivers created a sandbar that limited passage of large ships farther north. This combination of transportation accessibility and potential trading partners, combined with the high ground necessary for defense against attack and flood, made the site ideal for a fort and trading post. Sutter returned to Monterey after his survey and indicated the site as his choice. Governor Alvarado, charged with encouraging inland settlement in Alta California, awarded the grant to Sutter as a way to bring a larger European population inland.

As a naturalized Mexican citizen, Sutter’s land grant made him the ruler of Mexico’s first inland settlement in California. The adobe fort served as a military base, trading post and, despite the Mexican government’s wishes, an entry point for illegal emigrants from the United States. Sutter’s power was based on the land grant, a lack of competition and his ability to dominate the Nisenan and play them against the neighboring Miwok. He introduced himself to his new neighbors with plentiful gifts but also demonstrated the power of his cannon. Sutter’s combination of charm, fear and discipline turned the local Nisenan into his workforce, his soldiers and occasionally his merchandise. They were not technically slaves, but Sutter did give several Nisenan girls away as gifts to his neighbors. He also rented Nisenan laborers to other settlers, who then paid Sutter for their work.

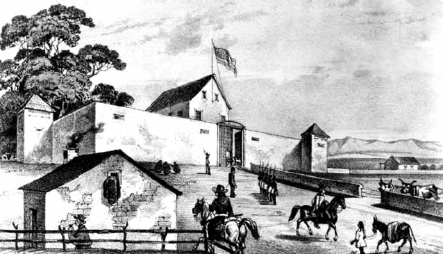

Sutter’s fort was a military encampment, trading post and production facility. The land the Nisenan cultivated for tule reeds and acorns was planted with grain and vegetables and was used to graze cattle, but agriculture was secondary to industrial production within the fort. Products like leather, blankets, clothing and baskets utilized the Nisenan’s skills at handicrafts. These goods were traded for iron, which Sutter’s blacksmith shops forged into tools that were sold to settlers. Grain and lumber mills increased Sutter’s ability to convert natural resources and newly planted crops into marketable trade goods.5

Sutter’s Fort. Center for Sacramento History.

While European workers were paid in cash, the Nisenan workers were paid using tin discs that were punched with holes to represent a day’s labor. This credit system kept the Nisenan economically dependent on Sutter because the discs could only be redeemed at his trading post. Observance of cultural tradition was not permitted if it interfered with Sutter’s production schedules. Following a traditional dance that left his laborers too exhausted to work the next day, Sutter burned down their dance huts in reprisal. Through their labor, the Nisenan became the most valuable commodity in Sutter’s growing economic empire. They produced the goods Sutter marketed to settlers and traders arriving from the north, east and downriver to Yerba Buena, the frontier settlement that later became San Francisco. Dressed in Russian uniforms purchased on credit, they also served as Sutter’s army.

While settlers and sojourners often stopped at Sutter’s Fort to trade and resupply, they seldom settled near the fort. In 1844, Sutter tried to promote settlement by laying out the town of Sutterville on a bluff along the Sacramento River, about three miles south of the American River. A path leading directly to the confluence of the two rivers was already established, but Sutter knew that this path was prone to flooding in winter and thus poorly suited as a town site. This path to the riverfront started near the sandbar at what is now the foot of I Street and extended to the front entrance of Sutter’s fort (today near Twenty-Seventh and L Streets) and crossed the current site of K Street.

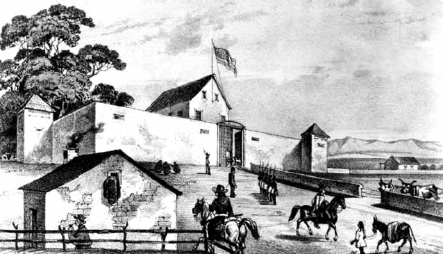

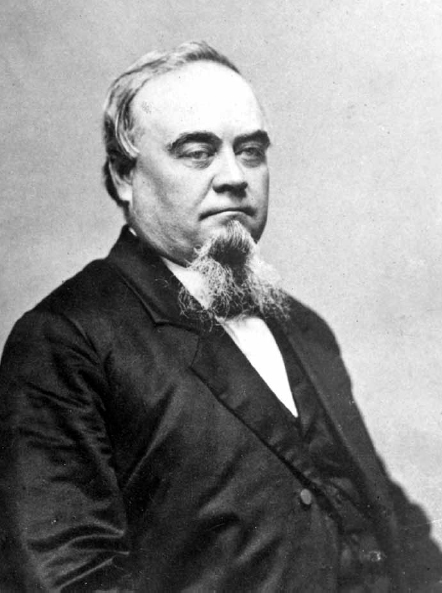

Sam Brannan. Center for Sacramento History.

Sutter and his Nisenan troops were captured while on a military expedition to Southern California in 1845, and by the time he returned to the fort, most of his Nisenan workforce was gone and a Miwok named Raphero led a rebellion against Sutter. Sutter captured and executed Raphero and displayed his head on a pike, an act that shocked and alienated the Miwok from Sutter. In 1846, the Mexican-American War brought California under United States control, and Colonel John C. Fremont took temporary command of the fort, renaming it Fort Sacramento. This political upheaval meant trouble for Sutter. Debts incurred from building and supplying the fort were overdue, and without his native workforce and unilateral control of his territory, he could not repay his creditors. Another of Sutter’s projects, a water-powered sawmill on the American River, had even more disastrous consequences for his empire when his employee James Marshall found flakes of gold in the mill’s tailrace. The coming gold rush spelled the end of Sutter’s empire, and the soft adobe walls of his fort crumbled not long afterward.6

Sam Brannan, a Mormon trader from Maine, saw opportunity along the path of K Street. Arriving in California in 1846, he established a store at Sutter’s Fort in 1847. Realizing a gold rush was coming after Marshall’s discovery, he asked Sutter’s land agent, Lanford Hastings, for free lots in Sutterville, Sutter’s planned city southeast of the fort. Hastings refused, so Brannan set his tents just south of the American River sandbar, near the site of a river ferry owned by George McDougal, who also used his ferryboat as a general store. Other than the trail to the fort, there was no formal street layout, but Brannan’s location was along Front Street, somewhere between I and K Streets’ later locations. He may have realized the risk of flood but considered it minimal compared to the coming flood of profits. Brannan’s cries of “Gold! Gold, from the American River!” through the streets of San Francisco in May 1848, shortly after buying every digging implement he could find, marked the start of the California gold rush. Sutter’s embarcadero was closer to the gold country than Sutterville and on the already established trade route, so the first wave of gold-seekers left the river at the front door of Brannan’s new store. The relatively dry winter of 1848–49, as well as the enormous profits from the sale of hardware and supplies to the first wave of miners, inspired Brannan to establish the area as a permanent settlement.7

Sutter’s mounting debts and circling creditors led him to transfer his property to John Sutter Jr., his son who had recently arrived from Switzerland, while Sutter Sr. departed for the foothills in search of gold. Sutter Jr. was twenty years old and spoke little English. Brannan proposed a way for Sutter Jr. to solve his father’s debt problems by subdividing and selling lots in a new settlement, Sacramento City, on the land between the fort and the Sacramento River. They hired recently arrived lawyer Peter Burnett to act as land agent. Captain William Warner of the Army Corps of Engineers, assisted by Lieutenants William Tecumseh Sherman and O.C.E. Ord, was hired to lay out a city plan in the fall of 1848. The blocks were 320 feet east–west by 340 feet north–south, including a 20-foot-wide alley with 80-foot-wide streets (except for M Street, which is 100 feet wide) and an extra 80 feet in the block between Twelfth and Thirteenth Streets. The north–south streets were numbered and the east–west streets were lettered. The first lots were auctioned off on January 8, 1849, although Brannan’s building on Front Street between J and K was already under construction by that date.8

Brannan understood that whoever controlled the waterfront of the new city of Sacramento had an enormous economic advantage. The ferryboat operator, George McDougal, claimed his lease from John Sutter Sr. covered the entire waterfront, but Brannan convinced John Jr. to challenge the lease in court. McDougal lost his claim and moved to Sutterville, then lowered his prices to compete directly with Brannan. Brannan responded with sabotage, destroying McDougal’s stock. Brannan also made an offer to Sutterville land agent Lanford Hastings to relocate his store to Sutterville in exchange for 80 lots of free land. Hastings accepted, hoping to capture Sacramento’s business, but Brannan went directly to Sutter Jr. and asked for a counteroffer to keep him in Sacramento. Sutter Jr. gave Brannan 500 city lots in return for a promise to stay in Sacramento. McDougal went to John Sutter Sr. to seek relief. Sutter left his winter camp at Coloma in a desperate effort to salvage what was left of his grant, but in the end all he could do was fire Peter Burnett. Because Sutter did not have enough money to pay the lawyer’s fee as his land agent, Burnett was paid in lots of Sacramento land. By early 1849, McDougal, Lanford Hastings, Sutter and his son and the vision of Sutterville had been defeated. The first city charter was approved by voters in October 1849, approved by the state legislature on February 27, 1850, and formally incorporated on March 18, 1850.9 The Sacramento City settlement became the city of Sacramento.

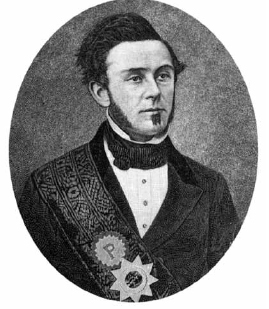

TERMINUS ON K STREET

In 1849, the Sacramento River levee at the foot of K Street was the arrival point for Argonauts seeking gold on the banks of the American River. As news of the gold rush reached the East Coast and the rest of the world, hundreds of thousands poured in via the Golden Gate and continued up the Sacramento River to the new city’s doorstep. Sacramento’s central location and river access for large sailing ships made it the busiest inland port in the state. Travelers stepping off the gangplanks at the foot of K Street were met with a row of hardware stores, grocers, hotels, gambling dens and taverns. Ships abandoned by gold-hungry crews became floating warehouses for Sacramento merchants called “storeships.” By May 1850, thirty-three storeships were permanently moored at the levee. The riverfront businesses equipped and refreshed new arrivals and provided a provisioning center and recreation area for those returning from the goldfields.

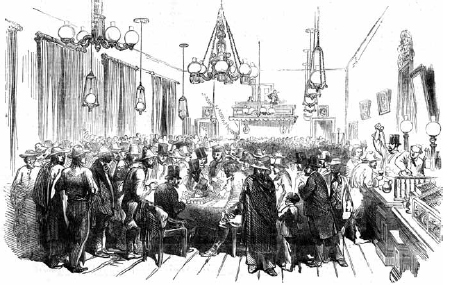

Sacramento’s waterfront in 1850. Center for Sacramento History.

Interior of a Sacramento gambling hall. Center for Sacramento History.

The first steamboat to operate on the Sacramento River was the Sitka, a boat so slow that on its inaugural voyage several passengers disembarked to continue on foot and actually beat the Sitka to San Francisco Bay. By 1850, large steam-powered side-wheeler steamboats worked between San Francisco and Sacramento, including the Senator, New World, Wilson G. Hunt and Antelope. A multitude of smaller steamboats, including the Governor Dana and Young America, worked farther north and in tributaries of the Sacramento River as far as Marysville and Red Bluff, where the large boats could not go.10 By 1854, the California Steam Navigation Company had gained a controlling interest in river traffic between Sacramento and San Francisco, with a permanent riverfront dock established at the foot of K Street.

The first stagecoach service in Sacramento was inaugurated in 1849 by James E. Burch of New England, who charged two ounces of gold dust (worth $3,000 in today’s currency) for a trip from the foot of K Street in Sacramento to Coloma, a trip of about fifty miles. J Street rapidly became the route to the goldfields, used by miners on foot and the newly inaugurated stagecoach and drayage wagons, but the foot of K Street, the point where passengers disembarked from riverboats, became the hub of California’s new stagecoach network. Like the riverboat crews who carried passengers rather than abandon their craft at the Sacramento waterfront, these frontier capitalists decided gold was easier to obtain via the miners than directly from the river.11 In July 1852, the Wells Fargo Express Company opened its first offices in Sacramento and San Francisco simultaneously, connected by riverboat. San Francisco was the blue-water port and emerging financial center, but Sacramento was the crossroads of transportation and trade. The office at Front and J Street was a block from the K Street embarcadero.

SACRAMENTO IN THE 1850S: FLOOD, RIOT, CHOLERA, FIRE AND MORE FLOODS

John Sutter placed his fort on high ground several miles from the river to avoid flooding problems.12 Sam Brannan’s decision to locate Sacramento next to the river was a decision for short-term gain, but it had long-term consequences for the new city. Many new Sacramentans believed Brannan’s claims that the area was not subject to flood and were caught by surprise when the Sacramento River overran its banks through the new city in January 1850. In response to the flood, Sacramento businessman Hardin Bigelow urged the new city council to build a short levee from the American River, just north of the city, and three miles to the south, near Sutterville. Dissatisfied with the city’s response to the plan, Bigelow hired a work crew and constructed the levee on his own. While his project was underway, Bigelow was elected Sacramento’s first mayor, and shortly after his election, the levee was officially authorized.13

Bigelow’s administration was cut short by the Squatter’s Riot in August 1850. Property owners and speculators who purchased official city lots came into conflict with settlers who argued Sutter’s Mexican land grant was invalid, allowing them to occupy vacant land without a deed. The riot ended months of escalating debate, legal battles, assaults and arrests (including that of future Sacramento Bee founder, James McClatchy) between the Settler’s Association, representing the squatters, and the city’s common council, representing holders of Sutter deeds. On August 12, Mayor Bigelow and Sacramento sheriff Charles Robinson moved to evict a squatter, but Mexican War veteran John Maloney and a force of fifty armed men stood in their way. Mayor Bigelow called out to the public to take up arms. Two large armed mobs met at Fourth and J Streets, one supporting the squatters, the other, the speculators.

The standoff was broken when Maloney shouted, “Shoot the Mayor; shoot the Mayor!” Both sides exchanged gunfire, killing four men and wounding five, including Mayor Bigelow, who was shot four times but not killed. Bigelow’s injuries were so serious that he was moved to San Francisco, where he died of cholera in October. This outbreak of cholera spread to Sacramento that same month, transmitted by a passenger on the riverboat New World.

The city flooded again in 1851, 1852 and 1853. After four years of regular floods, Sacramento property owners agreed to pay to elevate the city streets. This brought the city’s elevation up one to five feet, using Plaza Park at Tenth and J Streets as a baseline. Buildings in the raised district raised their street-side entrances by three to four feet to meet the new level of the sidewalks. Combined with levee improvements, this early street-raising project cost approximately $200,000 and kept Sacramento relatively dry through the remainder of the 1850s.14

Each time Sacramento flooded, Sacramentans temporarily moved east about four miles, near the vicinity of present-day Sacramento State University. During the 1850 flood, this high ground was called New Sacramento; it was called Hoboken in 1853 and, in the 1852 flood, property owner Sam Norris modestly named it Norristown.15 Each time floodwaters receded from Sacramento’s city site, the settlers returned from high ground to rebuild by the river. While the flood risk was undeniable, Sacramento was simply too valuable as a center of commerce to abandon. Its critical location outweighed the hazards. Sacramento had already become the second largest city in California, with thirteen thousand residents, a growing network of riverboats and wagon roads to the gold country and smaller towns throughout the valley. Proximity to the Sacramento River also linked the town to San Francisco and the Pacific coast. Sacramento’s location may not have made sense, but it did make money.

On November 2, 1852, another disaster struck. A fire started in Madame Lanos’s millinery shop on the north side of J Street at Fourth Street and spread to adjoining buildings. Sacramento was particularly vulnerable to fire, as most construction was of wood and canvas, with only a few brick buildings. Dry weather and strong winds blew burning coals to the southeast. In less than ten minutes, the fire had spread a block south to K Street. Sacramento’s handful of fledgling fire companies were rapidly overwhelmed by the scale and size of the fire. The final path of the fire destroyed everything on J Street east toward Ninth Street, and on K Street the devastation spread to Twelfth on both sides of the street.

On the following morning, survivors and salvaged property were crowded on the Front Street levee. Steamboats and stagecoaches dispatched in all directions from K Street summoned help. Within two days, citizens of Marysville started gathering donations for a relief effort, and performers in San Francisco arranged benefit concerts to raise repair funds. Lumber and even ready-made houses were loaded onto riverboats and barges for shipment. The massive demand for wood caused a dramatic spike in lumber prices. Rumors spread that speculators had raced to San Francisco to buy up stocks of lumber before news of the fire had even arrived, hoping to sell the lumber at a quick profit. Within a month, reconstruction of Sacramento was already underway, and some property owners used brick as a more fireproof alternative.

Sacramentans redoubled their efforts to build a city that would endure future disaster, including another flood on New Year’s Day 1853, less than two months after the fire. These efforts also included fire protection, including water cisterns on J and K Streets and two new volunteer fire companies. In order to supply these cisterns and the fire departments, a plan for a new city waterworks was needed. The citizens of Sacramento approved a tax to pay for a waterworks but rejected both of the proposed plans to build one, so the city council prepared its own plan for a municipal waterworks constructed at Front and I Streets, completed on April 1, 1854.16 K Street was also paved for the first time in 1853, using planks of Oregon fir and California pine; the paving stretched from the river to Eighth Street.

THE EARLY K STREET BUSINESSMEN: CROCKER, STANFORD, HOPKINS AND HUNTINGTON

Charles Crocker arrived in California in 1850 from New York with his brothers Clark and Henry, establishing a store in an El Dorado County mining camp. Charles’s job was driving freight wagons from the K Street dock to their store. This venture was successful, and by 1852, they decided to open a store in Sacramento at 246 J Street and were joined by their older brother, Edwin. Shortly after opening, this location was destroyed in the great 1852 fire. Fortunately for the Crocker brothers, Charles had traveled back to the East Coast to marry and returned with a large shipment of merchandise in March 1853, just in time for reconstruction of the store and profitable sales to others rebuilding in the wake of fire and flood.

Edwin Bryant Crocker, pioneer Sacramento businessman and civil rights attorney. Center for Sacramento History.

The rebuilt Crocker store combined dry goods downstairs and residences for Charles, Edwin and their wives upstairs. Edwin, who had worked as an attorney in the Crockers’ home state of New York, was admitted to the state bar and established the law firm of Crocker, McKune and Robinson in 1854. As the 1850s progressed and Sacramento was spared natural disasters for a few years, Charles’s dry goods business prospered, and Edwin pursued other interests, including gardening and viticulture. Edwin established the Sacramento Music Society in 1856 and served as its first president. He was also active in politics and the abolitionist movement. In New York, he had belonged to the antislavery Liberty Party and defended an escaped slave in Indiana in 1850. In 1856, he joined the fledgling Republican Party, whose platform opposed slavery and supported California pathfinder John C. Fremont as its presidential candidate. Edwin led the first Republican Party meeting on April 19, 1856. He also convinced his brother Charles to join, and through the Republicans, the Crockers met three other Sacramento businessmen: Leland Stanford, Mark Hopkins and Collis P. Huntington.17

While California was nominally a free state, slavery was a contentious political issue. Early Republican assemblies were disrupted by Cavalier Democrats, supporters of slavery in the southern United States, and representatives of the Native American (or “Know-Nothing”) Party. Many Southern Democrats, or Cavaliers, were interested in splitting California into two states, with “South California” as a slave state. The “Know-Nothings” opposed all immigration, including Catholics from Europe, and were powerful enough to elect their candidate, J. Neely Johnson, as California’s governor in 1856. Both groups opposed the Republicans’ pro-immigrant, antislavery stance, but some members of the so-called Tammany wing of the Democrats, aligned with Northern interests, were attracted to the new party. Another plank of the new Republican Party was a transcontinental railroad to reach California.18

Leland Stanford arrived in California in 1852, joining his brother Josiah, who came west in 1850, followed by another brother, Phillip. Like the Crockers, the Stanfords started with small shops in the mining camps but shifted their operations to Sacramento, where their businesses flourished. The Stanford store specialized in groceries and fresh produce and was located on L Street. When Josiah and Phillip opened an office in San Francisco, Leland took over the Sacramento store and distribution to outlying communities. In 1855, Leland briefly returned home to Albany, New York, originally intending to stay on the East Coast. His wife, Jane, expressed her dissatisfaction with Albany life in his absence, claiming that those in her social circle assumed he had abandoned her and treated her accordingly. Stanford returned to Sacramento shortly thereafter, bringing Jane with him.

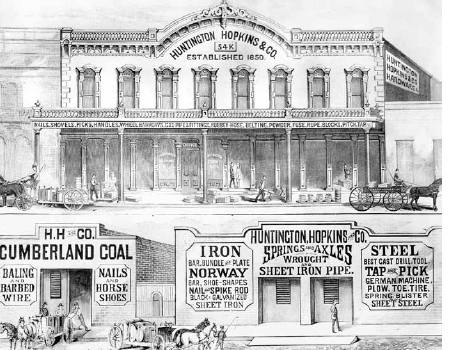

Huntington-Hopkins Hardware, 54 K Street. Center for Sacramento History.

In between the Crocker and Stanford stores on J and L Street was the Hopkins-Huntington Hardware Store at 54 K Street. Mark Hopkins and Collis P. Huntington came from New York to California separately, and like Crocker and Stanford, they had little interest in gold mining. At thirty-five years old, Mark Hopkins was considered an old man at the time of his arrival in California, where most gold-seekers were much younger men. He quickly made his reputation as a quiet, skilled accountant and bookkeeper, respected for his wisdom and earning the nickname “Uncle Mark.” Collis P. Huntington’s trading acumen was already proved by the time he arrived in California in the spring of 1850. On the journey to California, he increased his starting capital from $1,200 to $5,000 by trading with other passengers. Huntington and Hopkins specialized in hardware due to Huntington’s preference for non-perishable goods that could be stored while prices were low and sold when they were high. Number 54 K Street became the center for local business ventures that expanded the foot of K Street from a regional transportation hub to the connecting point for continent-spanning communication and transportation empires.19

CALIFORNIA’S FIRST RAILROAD AND K STREET

The Sacramento Valley Railroad (SVRR), the first steam railroad in the western United States, started construction in 1854 and was completed in 1856. The railroad was financed by Charles Lincoln Wilson of San Francisco, whose transportation empire also included riverboats on the Sacramento River and plank roads in San Francisco. Engineer Theodore Judah was solicited by Wilson to design the railroad. Its route stretched twenty-two miles from Sacramento to the city of Folsom. Judah had bigger dreams in mind for the railroad, imagining it as the first link in a transcontinental route. By 1860, SVRR had extended its Sacramento terminus from Front and R Streets to Front and K Streets. The SVRR had immediate consequences for K Street, as the speed and efficiency of railroad travel meant stagecoach and freight wagon traffic shifted from Sacramento to Folsom. The SVRR was originally intended to serve the goldfields along the American River, but by the mid-1850s, the gold rush was already slowing down. The fledgling railroad received a large economic boost when the Comstock Lode, an enormous silver strike in Nevada, started another economic boom. Wilson’s railroad sped the flow of materials, men and money from the Nevada silver mines to San Francisco via the Sacramento waterfront. The original terminus for the SVRR in Sacramento was at Second and R Streets, but by 1860, it had established a new passenger depot just south of K Street along the river levee. This pioneer railroad placed Sacramento in a critical location between the growing metropolis of San Francisco and the mineral resources that sent wealth to the bay, bringing more wealth and development to Sacramento, California’s second largest city and, in 1854, its new capitol.20

FIGHTING SLAVERY ON K STREET: THE STORY OF ARCHY LEE

In 1857, Sacramento became the site of a court battle between an escaped slave, Archy Lee, and his former owner. California law prior to the Civil War did not permit slavery for permanent residents, but slave-owning sojourners temporarily in California were allowed to keep them. With the help of Sacramento’s small but politically active African American community, Archy challenged this rule and gained his freedom. The resulting struggle was an early victory in American civil rights that began on K Street.

Archy Lee was born a slave in Mississippi and was brought to Sacramento by Charles Stovall. They arrived in Sacramento on October 2, 1857. During his stay in Sacramento, Lee met Charles Hackett and Charles W. Parker, the African American owners of the Hackett House Hotel at the corner of Third and K Streets. Hackett House was the center of Sacramento’s small but politically organized African American community. In a state where most whites were divided between those who wanted to exclude nonwhites entirely and those who wanted California to become a slave state, the black community’s need for organization was obvious. By 1857, they had established two churches, St. Andrew’s African Methodist Episcopal in 1850 and Siloam Baptist Church in 1856. They also established a public school and several local businesses and hosted statewide “Colored Convention” events to advocate for civil rights.

In January 1858, Stovall decided to return to Mississippi. Lee resisted by taking refuge at Hackett House. Stovall sought assistance from the Sacramento County sheriff and had Lee arrested. Shortly after Archy’s arrest, Charles Parker of Hackett House approached Edwin Crocker’s law firm to defend Archy. Crocker and his partner, John McKane, accepted the case.

The decision of Judge Robert Robinson on January 26, 1858, was that Archy was a free man because Stovall was a permanent resident of California and thus could not own slaves. However, Stovall arranged for a second arrest warrant by appealing to the state’s Supreme Court, and Lee found himself before another judge. In 1858, California’s Supreme Court was located in the Jansen Building at Fourth and J Streets, just over a block from Hackett House.

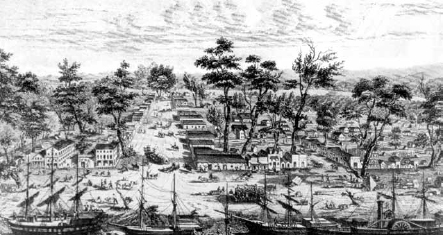

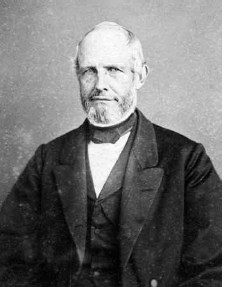

State Supreme Court justice Peter Burnett, formerly John Sutter Jr.’s land agent and California’s first elected governor, was also an ardent racist. While a member of the Oregon legislature before moving to California, he authored a bill banning African Americans from the state, punishing those who chose to remain by flogging them every six months. While governor of California, he attempted to pass a bill banning them from California entirely, whether slave or free. On February 11, 1858, Judge Burnett handed down a very unusual decision, supported by fellow Supreme Court justice David Terry (a Southern Democrat who fled the state the following year after killing antislavery advocate David Broderick in a duel). While California law prohibited slave ownership for state residents, Burnett decided that Stovall’s inexperience and poor health was sufficient reason to grant him leniency. Thus, in his opinion, Lee was Stovall’s property and had to leave California with him.

Peter Burnett, John Sutter Jr.’s land agent, California’s first elected governor and Supreme Court justice during the Archy Lee case. Center for Sacramento History.

Most Californians, especially in the African American community, were outraged by the absurdity of this decision. On March 5, Stovall tried to sneak Lee out of California on the ship Orizaba but was stopped by representatives of the Colored Convention. This time, both Lee and Stovall were taken into custody, Lee for safekeeping and Stovall for holding a slave illegally.

Two more trials awaited Archy Lee. In March, abolitionists and African Americans assembled another team of attorneys, and Judge Thomas W. Freelon of the San Francisco district court overturned Burnett’s decision. Stovall made a final plea to United States commissioner William Penn Johnston, a Southerner, arguing that Lee was in violation of the 1850 National Fugitive Slave Law. They hoped that Johnston’s status as a federal official would trump California state law. Lee’s San Francisco attorney, Edwin T. Baker, argued that since Lee had attempted to escape Stovall’s bondage while in California, no state lines were crossed and thus no federal case could be established. Johnston agreed, and on April 14, 1858, Archy Lee was declared a free man.

Lee joined an expedition of African Americans resettling in Victoria, British Columbia, but later returned to California. In 1873, several newspapers in San Francisco and Sacramento reported that Lee was found ill near the bank of the American River and was taken to the county hospital, where he died. Lee’s victory created a legal precedent that helped others escape slavery and promoted the abolitionist cause in Sacramento, via institutions like Hackett House and antislavery attorneys like Edwin Crocker.21