CHAPTER THREE

PROGRESS AND PROSPERITY

The lower quarter was not exclusively a Mexican barrio but a mix of many nationalities. Between L and N Streets two blocks from us, the Japanese had taken over. Their homes were in the alleys behind shops, which they advertised with signs covered with black scribbles…The Portuguese and Italian families gathered in their own neighborhoods along Fourth and Fifth Streets southward toward the Y Street levee. The Poles, Yugo-Slavs, and Koreans, too few to take over any particular part of it, were scattered throughout the barrio. Black men drifted in and out of town, working the waterfront. It was a kaleidoscope of colors and languages and customs that surprised and absorbed me at every turn.”

—Ernesto Galarza, Barrio Boy

By the dawn of the twentieth century, Sacramento had turned its location into its main advantage. At the center of an enormous agricultural region, and with multiple transportation routes, the city became the processing center for agricultural and natural resources for the entire valley. Sacramento’s earliest generation of businessmen, including Sam Brannan and the Central Pacific’s Big Four, had moved from Sacramento to San Francisco, taking their fortunes with them. While San Francisco’s wealth came from gold and silver mining in the Sierra Nevada, Sacramento’s wealth came from its surrounding farm regions, converting agricultural products into transportable commodities. Sacramento’s first millionaires took their fortunes and moved to San Francisco, but a second generation of businessmen emerged to take the earlier businessmen’s place on K Street. Often, these businessmen also had economic interests in regional agriculture.

California agriculture followed a different model than the family farm found across much of the United States. Sacramento and San Joaquin Valley farms were much larger, investor-owned operations. Instead of tenant farmers who lived on the land, most of the work was performed by migrant laborers, who worked intensely during planting and harvest seasons but were not employed by the farm during the rest of the year. Historian Carey McWilliams called them “Factories in the Field,” the agricultural equivalent of the nineteenth-century factories of the Industrial Revolution. Many Sacramento Valley farm owners were businessmen who lived in Sacramento. The migrant laborers who worked their farms also lived in Sacramento in between planting and harvest seasons, in hotels and boardinghouses near the waterfront and in the immigrant neighborhoods along the western end of K Street. These workers shared quarters with the thousands who worked in waterfront industries, the Southern Pacific Shops and yards, the city docks and the multitude of canneries, mills, lumberyards and other industries along the Front Street levee.

In The California Progressives, historian George Mowry identified the Progressives of the early twentieth century as a middle-class phenomenon, primarily consisting of conservative Republicans. In 1893, the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago prompted American cities to rethink their architecture and city planning. An economic panic in 1893 spurred a wave of labor unrest across the country, including the great Pullman Strike in 1894. The Populist movement united rural farmers in the 1870s and 1880s, an era of economic instability and alternating market bubbles and panics. The Progressive movement of the 1890s followed the Populist movement, but it emerged from the urban middle class, calling for greater economic stability after the wild market fluctuations of the late twentieth century, as well as an end to business monopolies that raised prices and restricted competition. In Sacramento, many middle-class businessmen, including farm owners, became part of the Progressive movement. As the seat of state government, Sacramento became an important part of the Progressive era’s national legacy. Progressives saw monopolistic companies like Southern Pacific and Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) as threats to their own business interests due to their control over transportation and power rates. While the “Big Four” of Central Pacific (known as Southern Pacific by the 1890s) started out in Sacramento and battled San Francisco’s dominance, all had left Sacramento for residences in San Francisco by the mid-1870s, as did Sacramento hardware merchant Albert Gallatin before founding PG&E. Sacramento’s remaining businessmen considered this a betrayal but, due to their enormous role in the Sacramento economy, could not avoid doing business with them.42

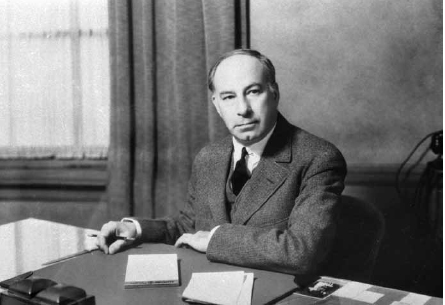

Sacramento native and California governor Hiram Johnson giving a speech in Sacramento. Center for Sacramento History.

Sacramento native Hiram Johnson was the leading figure of California progressivism in the early twentieth century. Born in 1866, Johnson was the son of attorney Grove Johnson, a member of the United States Congress in the 1890s and later the California legislature. Hiram grew up in Sacramento and after college joined his father’s law practice. He and his brother Albert worked on his father’s congressional campaign, but refused to endorse his reelection due to his support of the Southern Pacific Railroad, a schism that estranged Grove from his sons for many years. Hiram was appointed city attorney by Sacramento mayor George Clark in 1900 and began a crusade against gambling and other forms of vice in Sacramento’s pool halls and saloons. After helping reelect George Clark, Johnson moved to San Francisco, where his reputation as a crusader against corruption was made by prosecuting San Francisco mayor Eugene Schmitz and political boss Abraham Ruef in the wake of the 1906 earthquake and fire. He supported the Lincoln-Roosevelt League, an alliance of progressive Republicans, and was elected governor of California in 1910 as an anti-corruption crusader intent on limiting Southern Pacific’s power in California. With a native son in the Governor’s Mansion, Sacramento Progressives had much reason for optimism.43

THE SACRAMENTO CHAMBER OF COMMERCE AND THE RESTORATION OF SUTTER’S FORT

In September 1895, Sacramento’s business community formed the Sacramento Chamber of Commerce to foster business in the Sacramento region and encourage growth in the city. Its first office was on J Street, but most of the merchants who joined the chamber of commerce had commercial locations on K Street. They often used K Street as the site for parades, pageants and celebrations. The 1895 Grand Electric Carnival and the electric power it celebrated marked the beginning of a new era on K Street. It was a useful marketing tool and became the model for later festivals, but the real boon that the carnival celebrated was the advent of cheap, abundant and sustainable electric power.

During this era, K Street was the only place in the city with large department stores between Oakland and Reno, so it was a regional destination. Local streetcars and interurban trains shared the street with pedestrians, bicycles, horse-drawn carriages, wagons and even some automobiles. Between the department stores and specialty retail shops were theaters featuring vaudeville acts, dance halls and the new moving-picture theaters. Restaurants and bars in the business district satisfied Sacramentans’ hunger and thirst. K Street also featured hotels catering to travelers and visitors and apartments for downtown residents. Sacramento’s business district also had its underside in the form of gambling parlors, pool halls, taverns and brothels closer to the waterfront. Progressive members of the chamber of commerce criticized city government as too tolerant of vice and accused Southern Pacific and PG&E of undue influence at city hall.

On the eastern edge of K Street, Sutter’s Fort had seriously decayed, leaving only a central building by 1895. William Warner’s 1849 street plan ran L Street through the fort’s walls, and when growth on L Street pushed close enough to threaten the fort, local fraternal organizations (including the Society of California Pioneers and Native Sons of the Golden West) and the chamber of commerce intervened to protect the fort. They petitioned the city to curve L Street around the fort’s perimeter, raised funds to rebuild the fort’s walls and donated the reconstructed fort to the State of California for conversion to a museum and park.

The fort represented more than just a historic site to Sacramento’s Progressives. Up to the 1890s, Sutter was almost as forgotten as his fort, but like his fort’s reconstruction, his image as a historical figure was polished to meet a contemporary need. Instead of the semi-competent trader outwitted by merchants and overrun by miners, Sutter was portrayed as a visionary, whose dream of an agriculture-centered New Helvetia was crushed by greedy city builders and their hordes of immigrants, his pastoral farmlands polluted by mining and industry. This image of Sutter bore little similarity to Sutter the historic figure, but the resemblance to Sacramento’s agricultural entrepreneurs was unmistakable.44

This 1916 parade float on K Street demonstrated the solidarity of Sacramento’s Italian immigrants with their countrymen involved in World War I, even before the United States was officially involved in the conflict. The same parade also featured a similar float representing Portuguese soldiers. Center for Sacramento History.

Threatened by demolition in the 1890s, Sutter’s Fort became a symbol of the Progressive agrarian vision for Sacramento. Groups like the Native Sons of the Golden West and the Society of California Pioneers spearheaded efforts to rebuild the fort. The St. Francis Cathedral, constructed in 1910, sits behind the fort. Center for Sacramento History.

In June 1899, buoyed by the success of the Electric Carnival, a subcommittee of the chamber of commerce started plans for a new annual event. Established as the State Fair Club, its objective was to make better use of the state fair facilities, the racetrack at Twentieth and H Streets and the pavilion at Fifteenth and M Streets. The first Sacramento Street Fair and Trades Carnival, planned for April 30, was a weeklong celebration that used the state fair facilities, but much of the street fair took place on K Street and on adjacent business streets. Floral parades led by the Capital City Wheelmen, maypole dances, military marches and a three-hundred-foot long Chinese dragon march filled the streets of the business district, and chamber of commerce members hoped this event would fill hotel rooms and restaurants to capacity. 45

By 1903, the Street Fair and Trades Carnival had grown to the point where state senator Grove Johnson (Hiram Johnson’s father) remarked, “You’ve ruined the state fair by running your grand, magnificent and glorious street fairs!” After 1905, the state fair moved to new quarters on Stockton and Broadway, leaving the chamber of commerce without a downtown facility to host the fair.46

LIFE ON K STREET: HOTELS AND APARTMENTS, VAUDEVILLE AND MOVIE THEATERS

From the days of the gold rush, Sacramento businessmen like the Crocker brothers or Yee Fung Chung started out living in modest quarters above their stores in the downtown business district. Subsequent generations of small business owners followed the same patterns into the twentieth century. In Sacramento’s early days, when the business district only reached a few blocks inland, K Street still featured single-family residences, often interspersed with businesses. As the business district expanded, single-family homes along K Street were replaced by more intensive uses, both commercial and residential.

Some of Sacramento’s first buildings were hotels, intended for miners on their way to the mother lode or spending the winter in Sacramento before returning to their claim. The first purpose-built hotel was the City Hotel at 919 Front Street, constructed in 1849 using timbers originally intended for John Sutter’s flour mill near Brighton. By 1851, fifty-four hotels and forty boardinghouses were listed in the city directory. By the 1890s, a newer generation of elaborately designed hotels in popular architectural styles lined K Street and were just a short streetcar ride from Central Pacific’s new Gothic Revival arcade depot at Second and H Streets, which replaced its original passenger depot at Front and K Streets in 1879. Many of the gold rush–era hotels not destroyed by subsequent floods and fires were demoted in status to inexpensive railroad hotels as the end of K Street nearest the waterfront took on a far more industrial character.

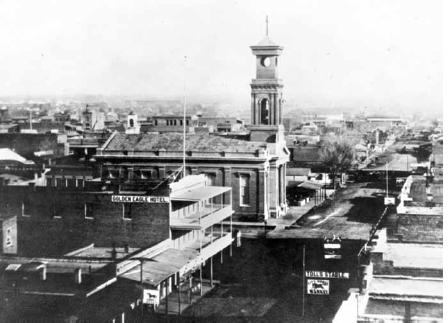

In the foreground are the Golden Eagle Hotel and the city horse market, circa 1868. Behind the hotel is St. Rose of Lima Church at Seventh and K Streets, Sacramento’s first Catholic church built on land donated by Peter Burnett in 1850. This version of the church was built in 1861, replacing an earlier wooden building. Center for Sacramento History.

Most of these hotels, both elegant and plain, were occupied by travelers or temporary sojourners, but many had long-term occupants. Waterfront hotels provided inexpensive winter quarters for migrant laborers. State senators, assemblymen and administrative aides lived in comfortable hotels just a few blocks from the capitol for months during the legislative season, returning home when the legislature adjourned. Others had estates or farms in the Sacramento Valley but needed a convenient place to stay while doing business in Sacramento. Professionals, business owners and elected officials called for a higher level of service than migrant farm workers, and the hotels where they lived reflected the status of their occupants.

Some K Street hotels, like the Golden Eagle, were reinvented by their owners to better serve the customers of the post–gold rush era. The original Golden Eagle Hotel was constructed in late 1850 by Daniel Callahan on two parcels near Seventh and K Streets, where a canvas structure first called Callahan’s Place stood. In 1851, Callahan built a wooden-frame building in the canvas structure’s place, but it did not survive the fire of 1852, so it was temporarily replaced with another canvas tent. In 1853, he mortgaged the property and bought another adjacent lot to build a new brick hotel, the Golden Eagle, with a granite front façade. This building was so fireproof it was credited with stopping the second great Sacramento fire in 1854. Due to the proximity of Sacramento’s horse market across K Street, the new Golden Eagle became a preferred residence of ranchers visiting Sacramento to trade livestock. As the business district expanded, nearby property owners lodged complaints about the smell from the horse market and the occasional policy of “test-driving” animals down the city’s thoroughfares at breakneck speeds. The ground floor of the Golden Eagle featured a restaurant called the Golden Eagle Oyster Saloon.

The building was elevated to the new grade and extended to the corner of Seventh and K Streets in 1867. By 1869, Callahan had completed a new Italianate façade that gave the Golden Eagle a stately grandeur. By 1870, Callahan’s neighbors included John Breuner’s furniture store, across K Street, and the St. Rose of Lima Church, Sacramento’s first Catholic church, just across Seventh Street. However, Callahan encountered financial difficulty and lost the Golden Eagle to his creditors, including John Breuner, in August 1874. According to Sacramento’s 1889 Blue Book social register, the Golden Eagle Hotel at 617 K Street was the home of People’s Savings Bank president William Beckman and also Warren O. Bowers, the new owner of the Golden Eagle.

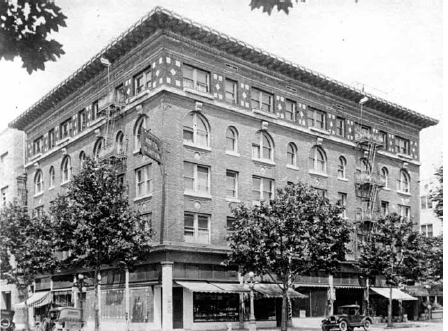

By 1902, the Golden Eagle was still home to some of Sacramento’s notables, but owner Warren O. Bowers had relocated to the Capital Hotel across K Street, a newer hotel with bay windows and fashionable Queen Anne architecture that replaced the odious horse market. Bowers came to Sacramento in 1867, working for the Central Pacific Railroad until 1878, when he purchased the Union Hotel on Second and K Streets. Other preferred hotels listed in Sacramento’s 1902 Blue Book include the State House Hotel and the Western Hotel, both at Tenth and K. Hotels like the Clunie, Coloma, Regis, Turclu, Berry, Californian, Ramona, Shasta and Argus provided rest for sojourners and more permanent homes for downtown residents. Many of these hotels were designed by prominent local architects, like the Hotel Sacramento at Tenth and K Streets, designed by former state architect George Sellon and built for Albert Bettens in 1910.47

While Sacramento’s hotels may not have met the standards of the finest palace hotels of New York and San Francisco, they were comfortable enough for many of Sacramento’s political class and business elite or those aspiring to that position. In 1919, young attorney Earl Warren lived in the Sequoia Hotel at 911 K Street, constructed in 1911, when he was a staff attorney for the California State Assembly Judiciary Committee. He later adopted more spacious quarters as governor or California.

In the early twentieth century, a new type of residential building appeared on K Street. Modern apartment buildings provided the proximity to job centers of older hotels but were intended for permanent residency. Instead of shared bathrooms, apartments had their own plumbing and often had kitchens, lessening apartment dwellers’ dependence on local restaurants or hotel room service. Apartment buildings like the Merrium, Maydestone, Francesca and Howe Apartments were generally not found directly on K Street, where businesses and hotels predominated. They were located on adjacent numbered streets within a block of K Street, providing convenient access to multiple downtown job centers.

The American Cash Apartments at 1117 Eighth Street, constructed in 1909, is a prime example of this sort of downtown apartment building. Designed by George Sellon in the Craftsman style, the ground floor housed the American Cash Store, a grocery store and the James Hays meat market, with twenty-four apartments composing its upper stories. Later commercial tenants included the J.Q. Fochetti Bakery, hat cleaner Wadyslaw Salmonki, the Muzio French-Italian Bakery, Otto Allen Liquors and the Fort Sutter Stamp Company. In 1938, the building was home to six laborers, two department store managers, three clerks, two railroad workers, a doctor, a nurse, a state commissioner and eight bartenders. By 1940, the building was renamed Bel-Vue Apartments.48

In 1895, K Street had three theaters: the Comique at 117 K, the Metropolitan between Fourth and Fifth Streets and the Clunie Theatre, attached to the Clunie Hotel, between Eighth and Ninth; the latter two were managed by J.H. Todd. Touring theater companies provided Sacramento with a variety of burlesque, vaudeville and traditional theatrical entertainment. One of the earliest movie theaters was Grauman’s at Sixth and J, where George Melies’s From the Earth to the Moon was shown in 1903, in addition to a vaudeville program. In the first decade of the twentieth century, many former vaudeville theaters showed early movies, and a handful of movie theaters converted existing buildings into movie houses. The Unique, opened in 1903, may have been the first opened as a movie theater rather than a vaudeville stage, but it later added live acts before relocating to 613 K Street in 1905. The same address operated as a theater under many names, including the Alisky in 1906, the Pantages in 1908, the Garrick in 1914, the T&D in 1917 and the Capitol in 1923, which it remained until 1957. Many Sacramento theaters operated under different names over the years, sometimes remodeling the building but often changing little more than the name on the sign.

The Hotel Sacramento and Hotel Land both sat on K Street, on opposite sides of Tenth Street. Both were built in 1910. They were primarily intended for travelers, but some of Sacramento’s most prominent citizens lived in downtown hotels, part time or full time. Across from the Hotel Sacramento was the Hippodrome, a vaudeville house and movie theater first constructed as the Empress Theatre. Center for Sacramento History.

Charles W. Godard operated multiple theaters on or near K Street, including the Liberty Theater at 617, the Majestic at 310 and the Acme at 1115 Seventh Street. His theaters focused on luxury and comfort, with modern heating and cooling systems, wicker loge seats and even a Japanese tearoom. The Empress opened at 1013 K Street on January 19, 1903, a two-thousand-seat vaudeville theater costing $150,000. The Empress featured a children’s nursery, smoking room, telephone booths and a modern ventilating system. But vaudeville was losing popularity to movies. In 1918, the Empress began showing films, and owner Marcus Loew changed its name to Loew’s Hippodrome, often called simply “the Hip.” A fire in August 1918 damaged the theater, ending vaudeville performances after fire repairs were complete, and a second fire in 1921 caused more damage.49

THE PROGRESS AND PROSPERITY COMMITTEE

By 1910, Sacramento’s gold rush era was long past, its role as western terminus of the Transcontinental Railroad superseded by Oakland and its place as the second largest California city long since lost to Los Angeles. Despite these setbacks, the chamber of commerce felt that Sacramento was poised for greatness and created a Progress and Prosperity Committee to focus on future plans for the city.

In 1909, a state referendum attempted to move the state capitol from Sacramento to Berkeley. The measure was defeated, but in response the Progress and Prosperity Committee sought recommendations for civic improvement by three of the most highly respected urban planners of the early twentieth century: Charles Mulford Robinson, Werner Hegemann and John Nolen. Between 1909 and 1915, after brief visits to Sacramento, each prepared a report recommending various changes.50

Charles Mulford Robinson’s report advised clearing the railroads from the waterfront and moving the industrial district north of the Southern Pacific Shops in order to allow beautification of the waterfront and creation of diagonal boulevards to allow direct access from Oak Park and other suburbs to the state capitol. He also recommended wholesale relocation of the American River, shifting its main channel south of Sacramento to allow unimpeded suburban expansion northward, beyond a new industrial zone north of the Southern Pacific Shops. Werner Hegemann recommended turning M Street into a grand boulevard and described K Street as “meaningless and vile.”

Park architect John Nolen’s plan included grand recommendations for a new Del Paso Park but was critical of high-density growth in downtown Sacramento, and in a November 1915 report to the chamber of commerce, he described the new generation of skyscrapers (the Forum Building on K Street and the Fruit Exchange on J Street, for example) as “an unqualified evil.” Sacramento’s business community was still centered on K Street, with the city’s entire population a one-mile walk or a short streetcar ride away. According to all three of the most eminent urban planners of the era, the future of Sacramento was in the suburbs to the north and east of the city limits.51

Sacramento’s new city hall building, completed in 1911, was first occupied by Mayor Marshall Beard, the last “strong mayor” of Sacramento. The 1893 strong mayor charter replaced the earlier 1863 charter’s three at-large trustees with a full-time executive mayor and a legislative board of trustees. This system was promoted by Sacramento’s business community and many founders of the chamber of commerce, who felt that more mayoral power would encourage businesslike efficiency and economy. Among the fifteen persons on the board of trustees elected in 1891 to rewrite the city charter were lawyer-industrialist and real estate developer Clinton L. White and department store magnate Harris Weinstock. Beard was a prominent member of Sacramento’s Democratic Party and a member of the chamber of commerce, and he held multiple elected positions, sitting on the city’s board of trustees and acting as superintendent of schools before being elected mayor in 1905 and again in 1911.

Beard was sometimes called “Boss Beard,” but many assumed the real power at city hall was held by board of trustees president E.P. Hammond and E.J. Carraghar, chair of the finance committee. Under this system, many residents felt that the city’s best interests took a backseat to big business interests. The strongest of those interests were Pacific Gas & Electric and the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Since its absorption of competing California railroads in the 1860s, Southern Pacific held an interstate transportation monopoly in northern California and had an enormous influence on state and local politics. The Southern Pacific Shops and Locomotive Works produced everything from hand tools to full-sized steam locomotives and was the main repair and supply facility for Southern Pacific’s national system. However, when Stanford, Crocker, Hunting and Hopkins moved from Sacramento to San Francisco, they took the railroad’s business offices with them. The company that formed to put Sacramento on an equal footing with San Francisco had left town. Reformers in Sacramento and throughout the state felt the railroad had too much influence on city politics, and its monopoly on transportation held Sacramento back while San Francisco reaped the benefits.52

ELECTRIC INTERURBANS LINK K STREET TO THE VALLEY

A phenomenon of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, interurban railroads served distances too long for a streetcar but too short for a steam railroad. Their passenger vehicles were also somewhere in between the two in size, powered by overhead electric wires or third rail and operable in multicar trains. Sacramento’s first interurban was Northern Electric, a route from Chico that reached Sacramento in 1907. Northern Electric’s Sacramento Depot was located at the corner of Eighth and J Streets, allowing shoppers from nearby cities and farm towns direct access to K Street, one block away. Northern Electric also operated freight trains, but it was forbidden from downtown Sacramento streets. Northern Electric operated local streetcars between K Street and McKinley Park on Alhambra Boulevard via C Street. Like the local PG&E streetcars, Northern Electric trains were powered by PG&E’s hydroelectric and oil-fired generators.

In 1911, Northern Electric built a railroad bridge across the Sacramento River at M Street as part of its expansion to the nearby city of Woodland and, in conjunction with the West Sacramento Land Company, started suburban streetcar service to its new suburb in 1913. This western branch was intended to become a new electric railroad to the Bay Area, the Vallejo & Northern, but was never completed. Another branch was added in 1913 to serve the new community of North Sacramento. Originally proposed to reach all the way to Orangevale, it, like the Vallejo & Northern, was never completed, and its route ended at the Swanston meatpacking plant. South of the M Street Bridge sat the river lines’ steam-powered riverboats, Capital City and Navajo, which made nightly runs from Sacramento to San Francisco. This new embarkation point at M Street moved riverboat traffic from its location at the foot of K Street.

Northern Electric abandoned its plans to build a route to the Bay Area when a competing electric railroad from Oakland, the Oakland & Antioch, arrived from the southeast, using the new M Street bridge (via a lease agreement with Northern Electric) to bring Bay Area and Sacramento Delta passengers to Sacramento. Its passenger depot crossed K Street at Third before stopping at the passenger depot at Second and I Streets, just south of the Southern Pacific Depot. The O&A later renamed itself the Oakland Antioch & Eastern but never built tracks to Antioch.53

From the south, another interurban, Central California Traction (CCT), which operated from Sacramento to Stockton, arrived in 1909. CCT’s route ran through Oak Park via Stockton Boulevard past the new California State Fairgrounds, shared Northern Electric’s freight route on X Street and terminated at its own depot at 1024 Eighth Street, half a block south of the Northern Electric Depot and just north of K Street. Like Northern Electric, Central California Traction also carried freight and operated a local streetcar between Eighth and K and the new suburbs of Colonial Heights and Colonial Acres, developed by affiliates of the interurban company. Electric power for CCT and its new suburbs was provided by the Great Western Power Company, a PG&E competitor.

The intersection of Eighth and K Streets was the hub of electric transit in the Sacramento Valley. On the left is a PG&E streetcar on K Street. On the right is a Central California Traction local streetcar and a Sacramento Northern interurban coach. From this corner, a traveler could reach Chico, Woodland, Oakland, Stockton or anywhere in Sacramento. Center for Sacramento History.

Three interurban railroads with separate facilities may have caused confusion for passengers, but in 1925, a union depot was built south of H Street between Eleventh and Twelfth Streets, facing an alley renamed Terminal Way. By 1926, all three interurbans stopped at the new Union Station, and in 1929, the lines that started as Northern Electric and Oakland & Antioch became a single railroad, the Sacramento Northern Railway. However, due to its importance as a shopping and business destination, Sacramento Northern and Central California Traction streetcars still met at Eighth and K Streets, and interurban trains stopped there on their way to or from Oakland and Stockton.54

WESTERN PACIFIC: THE LAST TRANSCONTINENTAL RAILROAD REACHES K STREET

Western Pacific, the last of America’s transcontinental railroads, was the western link of three roads all owned by financier George Jay Gould. Combined with the Denver & Rio Grande Western from Salt Lake City to Denver and the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy from Denver to Chicago, it competed directly with the giant Southern Pacific, breaking Southern Pacific’s monopoly on northern California railroad traffic. Western Pacific ran from Salt Lake City to Oakland, California, and passed directly through Sacramento. Prior to Western Pacific’s arrival, nearly every product shipped to or sent from Sacramento, and nearly every passenger entering or leaving Northern California, traveled on Southern Pacific trains, barges or riverboats.

Running a new steam railroad through Sacramento was not a simple proposition. Electric railroads, like the streetcar and interurban companies, obtained franchises to run on city streets from the board of trustees, but steam railroads were required to gain the written consent of two-thirds of the property owners adjoining the railroad. Realizing that this task was nearly impossible, primarily due to Southern Pacific’s interest in maintaining its monopoly, Western Pacific chief engineer V.C. Bogue planned a different approach outlined in a letter to the Sacramento Bee on October 7, 1907. Instead of running on a city street, Western Pacific purchased an eighty-foot right of way from property owners between Nineteenth and Twentieth Streets. Edward James Carraghar, the president of the Sacramento Board of Trustees in 1907, objected to the route because “it would practically destroy the very best residence district of our fair city.”55 Carraghar, owner of the Saddle Rock Tavern at Second and K Streets, was closely allied with Southern Pacific and the interests of the city waterfront.

This initial resistance to Western Pacific’s arrival prompted several proposals to mitigate the effects of steam locomotives running through a mostly residential district. Some advocated for an elevated railroad route to prevent trains from blocking streets, but others felt elevated railroad structures were an even greater hazard to the city. Western Pacific proposed landscaping its right of way into a parkway and building overhead crossings on the busiest pedestrian streets. While Western Pacific’s entry was opposed by the board of trustees, it had the full support of the chamber of commerce, which welcomed the railroad as a way to break Southern Pacific’s monopoly. The trustees voted against granting the franchise, so the chamber backed a public referendum to decide the issue. On October 22, 1907, Sacramento’s voters approved Western Pacific’s plan, and the way through Sacramento was ensured. Former chamber of commerce president Clinton L. White, a Progressive reformer, real estate developer and public opponent of the Southern Pacific, was elected mayor of Sacramento in the same election.

Western Pacific’s first passenger train operated on August 21, 1910. It gave Sacramento its second transcontinental railroad, bringing railroad competition and new jobs but not a real estate boom. Author’s collection.

Sacramento was a critical location for Western Pacific, due to its already-established role as the collection point and processing center for agricultural goods and natural resources in the Sacramento Valley. As the only major city between Salt Lake City and Oakland, Sacramento also had a large, skilled workforce and could supply the workers needed for Western Pacific’s planned main railroad shop. A subcommittee of the chamber of commerce, including Valentine S. McClatchy of the Sacramento Bee, William Schaw of Schaw Bros. Manufacturing, George W. Peltier of the California State Bank and real estate developer P.C. Drescher, bought properties south of Sacramento and gave the land to Western Pacific in January 1909 for use as a railroad shop.56

Sacramento’s Western Pacific passenger depot, located next to the new mainline between J and K Streets, was designed by Willis Polk, an architect of the D.H. Burnham Company of Chicago. It was considered one of Sacramento’s finest examples of the Mission Revival style, with deeply recessed quatrefoils in the gable ends, a clay tile roof and broad arcades to shelter passengers from both rain and sun. Its sprawling design stretched between Sacramento’s two main business streets and was accessible via streetcar lines on either end. For residents of the eastern half of Sacramento, including Sacramento’s growing middle class, the Western Pacific Depot was far more convenient than the Southern Pacific Depot downtown.

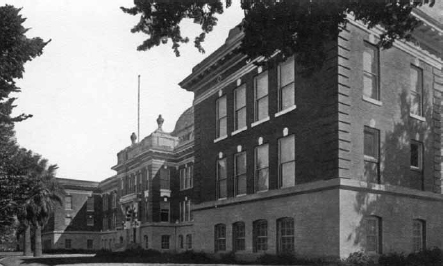

In 1908, Sacramento High School moved from its original location on M Street to Eighteenth and K Streets, closer to the Progressive middle-class neighborhoods and farther from downtown. It later became John Sutter Junior High School. Center for Sacramento History.

The building was completed in 1909, the same year that the Western Pacific began freight service, but passenger service had to wait until other facilities were completed. Western Pacific also constructed its main repair shop in Sacramento, hiring many Sacramento workers trained in the Southern Pacific Shops. The first day of passenger operation, August 21, 1910, came with considerable fanfare. The official timetable establishing passenger service was not adopted until the following day, with the first official train leaving Oakland for Salt Lake City on August 22.57

The arrival of the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad in Los Angeles in 1884 spurred an enormous Southern California real estate boom, and AT&SF’s arrival in San Francisco via the San Francisco & San Joaquin Valley Railroad in 1896 promoted similar growth in the Bay Area. The chamber of commerce was eager to see the same sort of growth in Sacramento. The era of political reform and anti-monopoly sentiment and the strong support of the chamber of commerce encouraged the city to accept this new competitor despite Southern Pacific’s influence.

However, Progressive regulatory reform already passed at the national level also limited the railroad rate wars. AT&SF’s arrival in Southern California caused an enormous housing bubble in the 1880s that turned Los Angeles from a quiet ranching town into California’s second biggest city. Sacramento grew because of the Western Pacific, but not to the dramatic extent seen in Los Angeles or the Bay Area, although it was also spared the devastating housing market crash that followed the bubble. Still, the beginning of Western Pacific service in 1909 and the opening of the Western Pacific Depot in August 1910 were as welcomed as the jobs at the Western Pacific Shops. The Jeffery Shops became Western Pacific’s primary maintenance facility, and their presence also gave Sacramento the unique distinction of being the only city in the United States containing two transcontinental railroads’ main shops.

THE LEGACIES OF DAVID LUBIN AND HARRIS WEINSTOCK

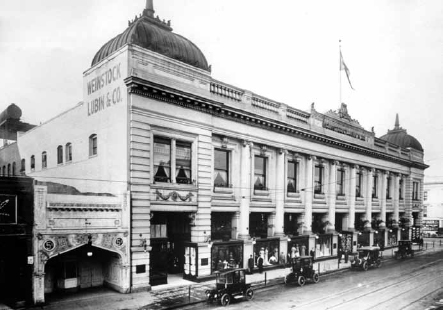

David Lubin was born in Poland on June 1, 1849. His family immigrated to New York City, where he grew up on the Lower East Side. Trained as a jewelry maker, he worked as a craftsman, gold prospector, traveling salesman and even as a cowboy. He arrived in Sacramento in October 1874, renting a small space at Fourth and K Streets where he opened a dry goods store. Three years later, he partnered with his half brother Harris Weinstock and expanded his Mechanic’s Store. In order to meet the Central Pacific Railroad Shops workers’ demands for durable work clothes, Lubin designed his own line of heavy-duty overalls manufactured in his store on K Street. By 1891, the Weinstock, Lubin & Company store marketed itself as the largest general retail establishment on the West Coast.

In the same year, they opened a grand four-story department store at Fourth and K Streets atop their original 120-square-foot retail space. The building was designed to resemble the A.T. Stewart Company Department Store on Broadway in New York City. The interior was a gigantic sales floor with an enormous light well and three levels of sales galleries around the building perimeter. A basement level even utilized the spaces under K Street’s sidewalks as part of the sales floor. Just as Sacramento’s first generation of entrepreneurs like Stanford and Crocker moved from Sacramento to San Francisco, men like Lubin and Weinstock took their place, building their homes along the H Street streetcar line through Alkali Flat, north of K Street and farther from the waterfront. Their neighbors included fellow K Street department store owner Edward W. Hale, new president of the Huntington-Hopkins Hardware empire Albert Gallatin and agricultural investor R.S. Carey.

Weinstock & Lubin Department Store, circa 1912, rebuilt after the 1904 fire. In 1924, a new location was built at Twelfth and K Streets, replacing this store. To the left of the department store is the Edison Theatre, one of Sacramento’s earliest movie theaters. Center for Sacramento History.

Lubin’s legacy went beyond his business empire. After an 1884 trip to Jerusalem, he experienced a crisis of conscience and sought ways to look beyond the needs of his business for personal fulfillment. In Sacramento, he helped form the California Museum Association and urged Margaret Crocker, the widow of Edwin Bryant Crocker (who had died in 1875), to leave her family’s art collection and its art gallery to the City of Sacramento to be maintained as a public museum. Margaret took his advice, donating the museum and its collection to the City of Sacramento in 1885. Weinstock and Lubin also helped establish the Crocker School of Design, and Lubin was instrumental in creating a state Indian Museum alongside the reconstructed Sutter Fort. While the Indian Museum was small, it became Sacramento’s first public institution dedicated to the people who had inhabited the land for millennia before Europeans arrived.

Lubin was also concerned with issues of world hunger and agricultural distribution. He established an experimental ranch north of Sacramento in Colusa County, researching methods of agricultural production. His research quickly proved that California’s potential for agriculture far outweighed the riches of its gold mines but limited means of distribution and that freight rates, as set by the Southern Pacific Railroad, meant the farmers of California saw minimal benefit from the value of their crops. The necessity of wholesale distribution limited the power of small farmers, giving the advantage to large landowners who could fill entire trains with goods. Lubin sought ways to connect the farmer directly with the consumer and eliminate the middlemen of distribution where possible.

Lubin’s experiments in the Sacramento Valley eventually led him to Rome, where he started an international organization to address the issues of world hunger and ways to modernize agronomy and worldwide food distribution. The International Institute of Agriculture lives on today as the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and is still headquartered in Rome.58

The Weinstock & Lubin Department Store expanded twice, adding annexes in 1900 and increasing the store’s frontage on K Street by forty feet in 1901. In 1898, the company opened a store in San Francisco. On January 31, 1903, the Sacramento store was destroyed by fire, and nine days later, the store opened temporary quarters at the former Agriculture Hall of the California State Fair located at Sixth and M Streets. A new store was completed on Fourth and K Streets in 1904, less than a year after the fire.59

David’s son Simon Lubin took over the Sacramento Weinstock & Lubin store until 1932 and followed his father’s example by entering into the world of social reform. In 1912, he was appointed president of California’s first Commission of Immigration and Housing by Governor Hiram Johnson.60

Harris Weinstock was born in London, England, in 1854. His family immigrated to the United States a year later, and he relocated to San Francisco in 1869. While David Lubin studied agriculture, Weinstock concerned himself with labor. Weinstock had experienced labor struggle directly while he was an officer in the California National Guard assigned to break the 1894 Pullman Strike at the Sacramento shops. The Weinstock & Lubin Department Store was well-known for its excellent labor relations and unionized labor force. In 1910, Weinstock was assigned by California governor James Gillett to prepare a report on the labor laws and conditions of Europe to see what California could learn in addressing labor problems. Weinstock traveled extensively in Europe with Lubin on behalf of the American Commission and was appointed to the Industrial Relations Commission by President Woodrow Wilson and Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan.61 In his 1910 report, Weinstock stated:

The idea of the worker being entitled to a voice in the matter of wages, hours of labor, or conditions of employment, seemed to the employer an impossible thought, and for the worker even to hint at such a right on his part was regarded as a bit of arrogance and a decided impertinence meriting instant dismissal. Conditions, however, have changed. Labor unionism has done much to educate the employer to the fact that the worker is entitled to a voice in all things affecting his own welfare. Trade unionism has through hard fought battles involving at times great industrial wars, with their frightful consequent sufferings to both sides and to society generally, forced upon even the most aristocratic and arrogant among employers the fact that it is a power to be reckoned with.62

Weinstock was even considered as a candidate for governor of California in 1910 by the Lincoln-Roosevelt League, an organization of progressive Republicans, but Weinstock, a supporter of Sacramento-born attorney Hiram Johnson’s gubernatorial campaign, refused to run.63

PROGRESSIVE PHILANTHROPISTS: WILLIAM LAND AND SARAH CLAYTON

Born in rural New York in 1837, William Land came to Sacramento in 1860, securing a job as a busboy at the Western Hotel on Second and K Streets. He married a housekeeper at the hotel, Katie Donnelly, but she died in 1870, followed less than a month later by their son Willie. By 1871, he had saved enough to buy the hotel where he worked. Tragedy struck again when the hotel burned down in 1875, but the indomitable Land rebuilt a more modern hotel on the same site. With 252 rooms and the city’s first passenger elevator and fire extinguisher, the hotel became an immediate success. Land bought another hotel, the State Hotel at Tenth and K Streets, and sold the Western in 1904. His new hotel, the Hotel Land, was constructed on the State Hotel site and completed in 1910.

Land had other business interests besides hotels, including business and residential real estate within the city of Sacramento and agricultural investments outside the city limits. He was an early president of the Sacramento Chamber of Commerce and was elected mayor of Sacramento in 1897.

William Land died on December 30, 1911, only a year after the opening of the hotel that bore his name. Lacking heirs, he left the bulk of his estate to churches, convents, orphanages and charitable organizations. He also bequeathed $250,000 to the City of Sacramento to purchase a public park. The location was unspecified, starting a fierce competition regarding where the park should go. Some members of the chamber of commerce suggested buying PG&E’s privately owned Joyland Park in Oak Park or renaming the recently acquired Del Paso Park after Land. This debate continued until 1922, when the site of William Land Park was chosen, the Swanston-McDevitt lot south of Sacramento. The park’s creation spurred suburban development around the new park site.64

During the late nineteenth century, the social roles of women were often as restrictive and stifling as the corsets and bustles of the era that were designed to make women conform to an idealized stereotype of womanhood. Despite these barriers, some women found important roles to play in their community. Sarah Clayton, wife of a Sacramento physician, became a living symbol of Progressive politics from a woman’s perspective in the city of Sacramento.

Born in Delaware in 1826, she became a schoolteacher in Bucyrus, Ohio, in 1846 and married Dr. Marion Clayton in 1851. In 1859, Dr. Clayton set out for California, leaving Sarah and their four children in Ohio. Rather than sit at home awaiting her husband’s call, Sarah became involved in philanthropic work. During the Civil War, Sarah worked for the Sanitary Commission, an organization dedicated to promoting modern sanitation methods in army camps and hospitals. Practices like bathing regularly, disposal of garbage and sewage and washing clothes were still very new ideas in the 1860s. Even doctors performing surgery seldom gave a thought to clearing viscera off the operating table or washing their hands before surgery. The Sanitary Commission served as hospital orderlies and trained medical staff and military commanders in disease prevention and sanitary techniques. The result was a profound drop in soldiers’ deaths from disease and infection. As secretary of the Sanitary Commission for five years, Mrs. Clayton learned about administration as well as sanitation.

In California, Dr. Clayton worked for eight years in Placerville before establishing a practice in Sacramento in 1867. Sarah and their children joined him in 1870, and shortly thereafter, they established the Pacific Water Cure and Health Institute at Seventh and L Streets. This facility provided “Turkish, Russian, electric and medicated water and vapor baths” to its patients. This facility combined Dr. Clayton’s medical skills with Sarah’s knowledge of sanitary principles. As a hydropathic physician in her own right, Sarah continued the management and operation of the Pacific Water Cure after Dr. Clayton’s death in 1892.

The Clayton Hotel, located at Seventh and L Streets, was constructed on the site of the Pacific Water Cure sanitary hospital in 1910 by Hattie C. Gardiner, daughter of Marion and Sarah Clayton. The hotel was renamed the Marshall in 1939, but the original name lived on through the 1950s through the Clayton Club, a jazz nightclub in the building’s basement. Center for Sacramento History.

Sarah found Sacramento an ideal place to pursue the goals of improved public sanitation. She noted the poor and unsanitary condition of the county hospital at Tenth and L Streets and convinced the county board of supervisors to establish a new county hospital on Stockton Boulevard, the current site of UC-Davis Medical Center. In addition to sanitation, Sarah was very involved with local orphanages. First a director for Sacramento’s Protestant Orphanage, she later established the Sacramento Foundlings’ Home, later renamed the Sacramento Children’s Home.

While social prejudices limited women’s careers greatly during her lifetime, women like Sarah Clayton rose above these limitations to make a difference in their communities and express their talents and intelligence. Many of these endeavors were considered “women’s work,” like childcare, nursing and teaching. Women like Sarah transcended traditional gender roles and influenced politics and policy on a local and sometimes even national scale. They also helped promote women’s suffrage by training a generation of young women in administrative and organizational skills and by encouraging their involvement in local political and social issues. Sarah Clayton died in 1911, the same year women gained the right to vote in California.65

O-FU: PROGRESS AND PROSPERITY IN JAPANTOWN

As new laws forbidding Chinese immigration went into effect, cultural changes in Japan allowed a new wave of Asian immigrants into the United States. Prior to 1884, Japanese workers were forbidden to leave Japan, and only a handful of Japanese had visited California. In that year, an agreement was signed between Japan and the United States to allow labor immigration, primarily for sugar plantations in Hawaii. By 1890, over one thousand Japanese lived in California, and communities like Sacramento’s Japantown appeared. The period of legal Japanese immigration was brief, ending with the 1907 Gentleman’s Agreement that prohibited further immigration of laborers. The first waves of Japanese laborers were overwhelmingly male, but the wives and children of Japanese workers in the United States were allowed to immigrate. Until further changes in immigration law were enacted in 1924, many Japanese women immigrated as “picture brides,” entering into arranged marriages with workers already in the United States. The gender imbalance was corrected quickly, and this first generation of Japanese immigrants, or Issei, soon produced a second generation of American-born Japanese, or Nisei.66

Sacramento quickly acquired the nickname “Sakura-mento” among Japanese immigrants. The Sakura, or cherry blossom, was a symbol rich with meaning for the Japanese, and their name for the Japanese community reflected this connection and its meaning. The Chinese character for “sakura” was sometimes pronounced “o,” and the term “fu” meant “capitol”; Sacramento then became O-fu, “cherry blossom capitol.” The first Japanese laborers arriving in Sacramento discovered they were not welcome in white boardinghouses, but by 1891, Sacramento had its first Japanese boardinghouse, the Tamagawa Inn. By 1909, there were thirty-seven boardinghouses in the newly established Japantown. From a population of 51 in 1890, Sacramento County’s Japanese population had reached 5,800 by 1920, the largest in the state except for Los Angeles (nearly 20,000.) Sacramento County’s considerably smaller population made Sacramento the most Japanese county in California. Japanese immigrants operated farms in rural communities like Florin, Perkins, Mayhew and Sutterville, while Japantown emerged between L and P Streets between Second and Sixth. The northern edge closest to K Street dealt the most with the rest of Sacramento, but a separate business district emerged along M Street that served Japantown’s needs more directly.67

Tametaro Kunishi Soda Fountain and Billiards, 1230 Second Street, part of O-fu’s business district. Center for Sacramento History.

Established prejudices and racial barriers separated Japantown from the mainstream of Sacramento life. The 1922 Ozawa v. United States Supreme Court case declared that Issei could not be naturalized as American citizens, and California’s 1913 Alien Land Law prohibited “aliens ineligible for citizenship” from owning land in California, a category that included all Asian immigrants. The size of Sacramento’s Japanese population was large enough for a level of relative autonomy, aided by kenjinkai, social organizations based on the immigrants’ home prefecture in Japan, and religious institutions including a Buddhist temple and Tenrikyo, Presbyterian, Episcopal and Methodist churches.

Ofu Kinyu Sha (Japanese Bank of Sacramento), Japantown’s first bank, opened in 1905 at 1007 Third Street, between J and K Streets. The first store selling Japanese goods opened in 1893, and by 1909, there were twelve grocery and general stores in Japantown, thirty-seven hotels, thirty-six restaurants, twenty-six barbershops, nine furnishing stores, three tofu makers and even a movie house, the Nippon Theatre on L and Third Streets. In 1913, druggist Tsunesaburo Miyakawa opened a Japanese hospital, Eagle Hospital, and later Agnes Hospital at 1409 Third Street in 1922, due to his dissatisfaction with treatment of Japanese at Sacramento’s county hospital.68

THE SACRAMENTO BARRIO

Japantown was not the only ethnic community south of K Street. Ernesto Galarza, born in the Mexican village of Jalcocótan, left Mexico in 1910 and came with his family to Sacramento, moving into a boardinghouse at 418 L Street. He described the end of town nearest the river as a mix of many nationalities. In addition to Chinatown and Japantown on both sides of K Street, he noticed the growing barrio of fellow refugees escaping political turmoil in Mexico, a small Filipino community and even a group of immigrants from India. The Indian community included “Big Singh,” a Sikh cook whom Galarza befriended despite their language barrier when he noted the similarities between the Indian roti flatbread and a Mexican tortilla.

Galarza’s childhood and adolescence in Sacramento revolved around the economic necessity of immigrants to take advantage of every opportunity for work and his enculturation through the Lincoln School, located at Fourth and P Streets. Sacramento’s immigrant communities were generally not large enough to justify separate public schools, so Lincoln School was highly racially integrated and, according to Galarza, encouraged multiculturalism and mutual respect. Teachers, led by principal Nettie Hopley, taught students American language, history and culture but never discouraged them from speaking their native languages or expressing their nation’s cultural practices. Galarza described Lincoln as “not so much a melting pot as a griddle where Miss Hopley and her helpers warmed knowledge into us and roasted racial hatreds out of us.”

Simon Lubin, president of Weinstock & Lubin Department Store and son of the store’s co-founder, David Lubin. Ernesto Galarza’s meeting with Lubin left a strong impression on Galarza, prompting his career as a labor activist. Center for Sacramento History.

As a teenager, Ernesto spent his summers working on farms and experienced firsthand the problems of migrant workers, a multicultural population with a growing number of Mexican immigrants. Because of his eloquence and skill with language, he was often asked to represent workers when dealing with authorities. In approximately 1920, Ernesto worked at a hop farm near Folsom, where several children were sickened by the polluted water from a drainage ditch that served as the workers’ water supply. One child had already died as a result, and Ernesto was asked to speak to a representative of the state labor board, Simon Lubin, son of department store founder David Lubin. Ernesto visited Simon Lubin at the Weinstock & Lubin Department Store on K Street. He explained the problems at the camp to Mr. Lubin, expecting little in the way of direct help, but with a result that surprised young Ernesto.

He heard me out, asked me questions and made notes on a pad. He promised that an inspector would come to the camp. I thanked him and thought the business of my visit was over; but Mr. Lubin did not break the handshake until he had said to tell the people in the camp to organize. Only by organizing, he told me, will they ever have decent places to live.69

In response to this meeting, Ernesto made his first organizing speech, and the workers voted to stop work until the inspector arrived. The inspector came, bringing a water tank to supply clean water to the camp. Ernesto was fired shortly thereafter by the contractor, but this activity began Galarza’s career as a labor activist and union organizer.