9English-German contrasts in cohesion and implications for translation69

Abstract: This study discusses findings from a corpus-based comparison of cohesive features in English and German written and spoken registers with a view to translation studies. We use several multivariate techniques to empirically analyse our corpus data and to interpret it with respect to four research questions. These concern contrastive differences in the overall degree of cohesion, in the strength of cohesive relations, the meaning relations established and the breadth of inter- and intralingual register variation. We hereby add a focus on semantic relations across grammatical domains to the available lexicogrammatical accounts of language contrast, which provides a background for making suggestions for translation strategies.

1Cohesion and contrastive linguistics: the added value for the study of translation

The present study discusses findings on cohesion in an English-German comparable corpus as a step towards deriving potential translation strategies for this language pair. We start from the claim that there are systemic and textual contrasts between English and German on the level of cohesion. Systemic contrasts in cohesion concern differences in the linguistic resources of the two languages to establish relations of meaning across grammatical domains, i.e. above the phrase level, between different clauses, sentences or larger stretches of text. The question here is which (cohesive) devices are available in each language to explicitly indicate particular cohesive relations to other linguistic expressions (called antecedent in the literature, especially in the case of coreference). We have discussed these differences in Kunz and Steiner (2012) for coreference, Kunz and Steiner (2013) for substitution, Kunz and Lapshinova-Koltunski (2014) for conjunction and Menzel (2014) for ellipsis. A summary of these studies is provided in section 2.

It is especially relevant for translation studies to see which of these resources are used and how they create cohesive relations in naturally occurring texts of English and German. Therefore, our focus is on identifying contrasts in the textual realizations of cohesion. This includes not only the investigation of the explicit signal, the cohesive device, but also the cohesive relation triggered. Depending on the type of cohesion, several cohesive devices may be used to create a cohesive chain, containing more than two linguistic elements and stretching over longer textual passages than two adjacent sentences. Knowledge about these textual contrasts between English and German original texts should impact on the conscious use of particular cohesive strategies when translating or interpreting within this language-pair.

1.1Motivation and main research objectives

Our research objective is not to draw any conclusions about properties of translation, or translationese, such as explicitation, standardization or interference (see e.g. Baker 1993; Toury 1995). We rather aim at complementing contrastive works on differences between English and German such as Hawkins (1986) or König and Gast (2012). While these approaches mainly focus on systemic features in lexicogrammar, our corpus-based work examines instantiations of textual relations across grammatical domains. Furthermore, the findings from our contrastive study are a point of departure for making suggestions about systematic and adequate translation strategies on the level of text/discourse. The importance of cohesion in general and of coreference resolution in particular has variously been addressed in the literature on translation (cf. among others Baker 1992: 180; Becher 2011: 55; Blum-Kulka 1986; Doherty 2002: 160; Fabricius-Hansen 1996; Hatim and Mason 1990: 192; House 2004; Königs 2011: 72), though usually in a programmatic or at best example-based way. Our study aims at a more comprehensive account and at one that has improved empirical grounding.

For this purpose, we compare corpora of English and German original texts in the first instance, rather than translations and originals. A contrastive study aiming at wide coverage requires accounting for the textual variation as a signal of variation in contextual configurations. Our corpus resource therefore comprises comparable subcorpora in 10 different English and German registers. In this way, we obtain findings about the cohesive norms informing general strategies for translations between the two languages. Additionally, the corpus constellation yields data on variation in different written70 and spoken registers and allows deriving register-specific translation (and interpreting) strategies.

Our approach goes beyond the investigation of individual cohesive phenomena. Following the classification by Halliday and Hasan (1976), our analyses cover various features of coreference, substitution, ellipsis, cohesive conjunction and lexical cohesion. Applying several statistical methods we capture language-and register-specific preferences as to the meaning relations that are established by cohesion, as to the forms to encode these relations, and as to the interaction of cohesive types.

1.2Research questions and methodology

Our research design addresses four research questions about English-German contrasts which are especially relevant for translation studies. Research questions (1), (2) and (4) are based on assumptions that have already been discussed in contrastive works, however mostly with a view to lexicogrammar, while to our knowledge, question (3) has not been addressed so far:

(1)How cohesive are the texts in our corpus?

(2)How strong are the cohesive relations?

(3)Which semantic relations are generally expressed and which relations are preferred over others?

(4)How much cohesive variation is there in one language as compared to the other? How much difference is there between (written and spoken) registers?

Several statistical methods are applied to evaluate our corpus data in terms of questions (1) to (4) and to obtain insights about a) English-German language contrast, b) register variation and, within register variation, c) variation between written and spoken modes.

Question (1) is a very general one and concerns contrasts in the overall degree of cohesion. The term implies the number of cohesive devices per linguistic unit occurring per text, i.e. tokens, not types. Some strands of contrastive pragmatics (e.g. House 1997: 84) suggest that German and English differ along the explicitness – implicitness dimension, with German showing a preference for expressing meaning more explicitly by linguistic signals than English. This assumption is supported for lexicogrammar, information packaging and grammatical metaphor (cf. Fabricius-Hansen 1996; Steiner 2005; Hansen-Schirra et al. 2012). We expect that these differences also manifest themselves in the choice of cohesive devices for explicitly indicating relations of coherence, i.e. at a deeper conceptual level of the text (cf. Beaugrande and Dressler 1981). Another assumption formulated in the literature is that variation in terms of cohesive vs. non-cohesive expressions per text depends not only on language, but also on register (following on from Hansen-Schirra et al. 2007: 249; Kunz 2010: 395). We particularly expect variation between written and spoken registers. The degree of cohesion should be higher in spoken than in written registers, along with reduced information density, less metaphorical semantics to grammar mapping and a looser grammatical structure, which cannot be dealt with in the frame of this study. All these features are said to reflect the particular constraints of oral communication such as reduced working memory capacity, speaker interaction or a noisy environment (cf. Halliday 1989: 41; Levy and Jaeger 2007).

The degree of cohesion is measured in our study by relating the total number of cohesive devices to the total number of tokens per corpus or subcorpus. Yet, a lower degree of cohesion in one language/register relative to another does not necessarily imply a lower degree of explicitness in general as encoding could be provided on a different linguistic level such as lexicogrammar.

Research question (2) considers differences in the strength of the cohesive relation71. The term strength of relation is chosen in this study to cover not only coreference but also other types of cohesion. Our focus is on the following two aspects:

(I)How explicitly is the relation indicated by linguistic signals in the cohesive device? This has to do with parameters such as semantic reduction vs. semantic specification; multifunctionality vs. single precise function of the cohesive device. Here again, we draw on literature on contrastive pragmatics to suggest that German may use rather specific/explicit cohesive devices to strengthen cohesive relations while in English cohesive relations may be vaguer, created by more underspecified/less explicit cohesive devices. Take, for instance, the coordinating conjunction and and its counterpart und in German. Both are semantically vague and may be applied for a variety of logico-semantic relations or even pragmatic functions (see e.g. Carston 2002). We expect a higher amount of more specific conjunctive devices in German to express relations of addition (e.g. darüber hinaus or außerdem). Additionally, we expect spoken registers to employ more cohesive devices than written registers overall (see question (1) above) but at the same time these devices may be shorter and semantically more underspecified. Structural indicators for measuring cohesive devices along the dimension of implicitness/explicitness or underspecification/specification in this study are elliptical constructions vs. other cohesive types, pronouns as nominal heads vs. determiners/modifiers (within coreference and substitution), connects vs. conjunctive adverbials (within cohesive conjunction). A cohesive relation is “strong” in the sense of (2) if it is specific in its encoding and functionally unambiguous.

(II)How much does the cohesive relation contribute to the overall textual or thematic coherence? Two more specific aspects can be addressed in the frame of this study: chain size (number of elements in one chain) and number of (different) chains: while higher numbers of elements in one chain contribute to thematic continuity, higher frequencies of different chains per text reflect thematic progression or variation. There are no assumptions in the literature suggesting contrasts in terms of cohesive relations. A cohesive relation is “strong” in the sense of question (2) if it occurs in a chain of many elements and/or if a text has many chains of its type.

The degree of cohesion (research question (1)) may or may not impact on the strength of relation: whenever high frequencies of cohesive devices are employed to establish the same type of relation – e.g. a succession of conjunctive devices to establish a temporal sequence or long coreference chains – the sequence or the coreference chain is strengthened. Yet, extensive use of cohesive devices may also translate into a high number of short chains, which are only of local relevance for the text.

Question (3) deals with differences in the type of meaning relations that are signalled by cohesion. Differences in the meaning relations expressed would point to different cultural preferences for expressing four main types of semantic relations which can be indicated on the basis of cohesion in English and German by the following cohesive types:

–Coreference: Identity between instantiated referents, mainly expressed by subtypes of personal and demonstrative coreference;

–Type reference: involving comparison between instantiated or generic referents belonging to the same referential type, expressed by subtypes of comparative reference, ellipsis and substitution;

–Similarity: Sense relations between different types of referents, expressed by lexical cohesion (general nouns);

–Logico-semantic relations: relations such addition, cause, time, contrast and manner as expressed by subtypes of cohesive conjunction (additive, causal, adversative, temporal and modal conjunctions).

Section 2 presents a discussion and exemplification of the cohesive types/devices realizing these meaning relations. To our knowledge, no studies exist that deal with contrasts along the dimension of meaning relations expressed by cohesive devices based on empirical data of the type offered here.

The research question can be approached from different angles for which we employ different statistical methods (see in more detail below): if we compare the two languages with respect to the distribution in percentage of the main cohesive types, we can see which type is more important for the overall cohesion in one language (or mode) than the other. Correspondence analysis shows how certain cohesive features cluster together and where the biggest differences and similarities lie: between languages or between registers (including spoken and written modes). On the other hand, text classification reveals those cohesive features which are (strongly) distinctive, i.e. which mainly contribute to the differences.

Question (4) finally examines differences in the breadth of variation between written and spoken registers of English and German. From a general perspective, this research question dives into language contrast by relating it to intralingual register variation. There are several works concerned with lexicogrammar suggesting that distinctions along the register dimensions of written vs. spoken, and formal vs. colloquial may be weaker in English than in German (Collins 2012; Leech et al. 2009: 20, 239; Mair 2006: 183). So far, this has not been seriously investigated for patterns of cohesion at all. We here attempt a first assessment for cohesion by examining differences in variation with respect to the research questions (1) to (3) raised above. The statistical methods will be correspondence analysis and text classification.

Knowledge about contrasts in terms of these four research questions by translators will impact on the local and possibly also on the global translation strategies that are consciously chosen for establishing textuality or coherence as well as thematic progression in texts. It may direct translators towards decisions such as the following in order to adhere to target language conventions on the level of cohesion:

–Generally explicitate textual relations which are left implicit in the source text by inserting cohesive devices in the target text.

–Move a textual relation that is preferred in the source text into the background in the target text by implicitating particular meaning relations and explicitating others.

–Make a vague cohesive relation stronger by using a more specific cohesive device or by using more cohesive devices in one cohesive chain.

–Use more different cohesive devices to mark one conceptual type of cohesive relation.

In addition, our study may shed light on whether any of these decisions generally holds for translating into a particular translation direction or whether it strongly depends on the register. Any recommendations made here are, of course, limited by the quantitative size and registerial spread of our corpus (cf. section 3.1 below). The fact that all of the written texts (approx. 1 million tokens) are published texts should at least provide a bottom line of quality assurance.

1.3Overview of sections

The chapter is structured as follows: section 2 will be concerned with a definition of cohesive types and an overview of contrasts between the English and German language systems as to the resources available for establishing cohesion. Section 3 will describe the corpus and outline the methodologies for annotating and querying cohesive features as well as the multivariate techniques for analysing our corpus data. Section 4 will describe the findings obtained by the multivariate techniques, which will then be interpreted with respect to our four research questions in section 5.

2Cohesion in English and German

2.1Cohesive types and semantic distinctions

The types and subtypes of cohesion discussed below are classified on the basis of English (following Halliday and Hasan 1976) and occur in our presentations and discussions of data in sections 3 and 4 of this chapter (cf. Table 1 later on). In order to be able to relate these types to each other in a cross-linguistic comparison, we need to specify the semantic distinctions which they encode. Research question 1 in section 1 (the overall degree of cohesion) requires a maximally comprehensive view of cohesive types/devices. For an investigation of research question 2 (the strength of the cohesive relation), we need the structural realization of the types. The differences in the type of meaning relations signalled by cohesion (research question 3) is accounted for by the semantic distinctions encoded in the different types of cohesive devices. Finally, differences in the breadth of variation between written and spoken registers of English and German (question 4) can be stated either in terms of devices or in terms of semantic distinctions – hence both cohesive types/devices and their semantic distinctions need to be part of our model.

The relationship of cohesive coreference encodes identity between textually instantiated entities, including events (cf. examples (1) and (2)).

(1)We work for prosperity and opportunity because they’re right. It’s the right thing to do. [EO_ESSAY]

(2)Wir arbeiten für Wohlstand und Chancen, weil das richtig ist. Wir tun damit das Richtige. [GTRANS_ESSAY]

‘We work for prosperity and opportunity because that is right. We do thereby the right’72

The English example (1) uses the personal reference pronouns they and It to corefer to the entities prosperity and opportunity in the first case, and to the event working for prosperity and opportunity in the second. The German corpus translation uses the demonstrative das and the demonstrative deictic damit, referring to the event working for prosperity and opportunity in both cases, but encoding an additional adverbial relation of instrument in the second. This is one of the typical cases of translation between English and German where the coreference relation as such is preserved, but it is not coreference exactly to the same entities in both cases, and it is semantically enriched by the instrumental relation in the second.

For coreference, we distinguish personal and demonstrative types. Their subtypes are based on their functions, e.g. acting as heads or modifiers in a text, or expressing local and temporal relations. Here, we also include demonstrative deictics and definite articles.

We separately analyse the category of coreference chains in terms of the number of referents and referring expressions in chains (antecedents and ana-phors), as well as the number of chains and chain length. Coreference chain is thus not a separate cohesive category, but the chain aspect of coreference. These data are included in our statistical analyses in sections 3 and 4, but are not extensively discussed in this chapter.

Comparative reference is semantically distinct from personal and demonstrative reference. It does not create identity of reference (coreference) but rather evokes a relation of comparison between referents, events or propositions of the same type (see e.g. Halliday and Matthiessen 2013: 632; Schubert 2008: 35). We here include two subtypes, which express general (see 3) or particular comparison (see 4).

(3)Although we believe privatization is beneficial, it is not part of the trade negotiations. Countries will continue to make such decisions for themselves. [EO_ESSAY]

(4)Ich habe diese einfache Art der Verschlüsselung nur deshalb gewählt, weil wir damit bei kleinen Zahlen bleiben, bei denen sich das Verfahren leichter nachvollziehen lässt. Eine bessere Möglichkeit bietet sich Herrn Weiss, wenn [. . .] [GO_POPSCI]

I chose this form of encryption only so we could keep to small numbers, where the operation is easier to follow. Mr. White, however, can choose a better way by [. . .] [ETRANS_POPSCI]

Similarly to comparative reference, cohesive substitution and ellipsis encode comparison between different entities of the same type, based on co-denotation of that presupposed type.

(5)In future studies of adult stem cell potential, it will be crucial to rule out the possibility that stem cells are merely fusing to local cells rather than generating new ones. [EO_POPSCI]

(6)Daher ist bei künftigen Studien zum wahren Potenzial von adulten Stammzellen unbedingt auszuschließen, daß die Zellen nur mit den lokal vorhandenen (0) verschmelzen, statt wunschgemäß neue (0) zu erzeugen. [GTRANS_POPSCI]

In the German translation of the English original in (6), we see first a change in the type of cohesive device (substitution one and lexical cells by German ellipses). Second, ellipsis and substitution by themselves do not encode coreference, but rather co-denotation (neue (0) in 6). The latter does not presuppose joint reference to the same individual entity, but rather joint denotation of the same class of entities. Another instance of this semantic relationship can be seen in the denotation of the various occurrences of cell(s) in (5).

For substitution and ellipsis we define categories depending on what is substituted or elided: nominal or verbal phrase, or their parts, a part of a clause or even a whole clause (nominal, verbal and clausal in Table 1).

Cohesive conjunction73 encodes logico-semantic relations between discourse units, usually propositions, such as addition, contrast, cause. We have already seen this in the adding of an instrumental adverbial relation in (2) above. (7) and (8) show the shift in the semantic type of conjunctive relation – in this case from adversative dagegen to additive moreover.

We again have the preservation of the general type of cohesive device (conjunctive relation), but a change in subtype, and hence in the encoded semantic relation.

(7)Dagegen ist das Gewicht der Bauwirtschaft mit 15 Prozent gegenüber Westdeutschland (4 Prozent) noch entschieden zu hoch. [GO_ESSAY]

(8)Moreover, the significance of the construction industry (15 %) remains much too high when compared with western Germany (4 %). [ETRANS_ESSAY]

Conjunctive relations are analysed in terms of the logico-semantic relations they explicitate between discourse segments in section 3 below: additive (relation of addition), adversative (relation of contrast or alternative), causal (relation of causality), temporal (time-relation between events) and modal (relation between events connected by an evaluation of the speaker). We also consider the restrictions in their syntactic function (coordinating conjunctions and conjunctive adverbials), and include them into our definition of types under analysis (additive connects, additive adverbials, etc. in Table 1). Subordinating conjunctions are excluded from our analysis as their encoding is grammatical, rather than cohesive only.

Lexical cohesion involves sense relations between lexical items (e.g. hyper-onymy, part-whole relations), yet also semantically weaker relationships of collocation (Halliday and Hasan 1976: 284).

(9)Sweetheart. That’s what that weather was called. Sweetheart weather, the prettiest day of the year. And that’s when it started. On a day so pure and steady trees preened. Standing in the middle of a concrete slab, scared for their lives, they preened. Silly, yes, but it was that kind of day [. . .] [EO_FICTION].

(10)HERZBLATT. So wurde das Wetter genannt. Herzblattwetter, der schönste Tag des Jahres. Und da hat es angefangen. An einem Tag so rein und beständig, daß die Bäume sich herausputzten. In der Mitte eines Stücks Beton, um ihr Leben besorgt, putzten sie sich das Gefieder. Albern, ja, aber so ein Tag war es. [GTRANS_FICTION]

In examples (9) and (10) from our corpus, we see a case where lexical cohesion is very much preserved. Notable exceptions are the variable translation of English preen as sich putzen, sich herausputzen, establishing a hyponymic relationship in German differently from English, and the translation of the English that kind of day using the general noun kind (of) by the German so ein Tag using the comparative reference item so for the English lexical expression.

There is no one-to-one relationship between semantic distinctions and patterns expressing them: coreference as a semantic relationship, for example, may be encoded in grammatical constructions or in cohesive configurations. And even within the latter, it may involve cohesive devices other than reference.

One further example for the multiple possible mapping relationships between semantics and variously lexicogrammar or cohesion is given below, this time using logico-semantic relations as an example (cf. (11) to (15)):

(11)The performance was followed by a round of applause.

(12)After the performance, there was a round of applause.

(13)After the performance ended, there was a round of applause.

(14)The performance ended. Afterwards, there was a round of applause.

(15)After the event, there was a round of applause.

The semantic relationship of temporal precedence is variously encoded in (11)–(15) through lexical, grammatical and cohesive devices. And in (15), it is additionally encoded through a combination of the grammatical preposition after, the demonstrative reference item the and the lexically cohesive hyponymy relationship between performance and event.

Most of the semantic distinctions encoded in cohesive devices can be expressed lexicogrammatically or cohesively across and even within languages – and we are particularly interested in the cohesive encoding and its systemic and instantial (textual) differences between English and German.

As we said at the beginning of this section, our classifications of cohesive devices are initially based on the account given for English in Halliday and Hasan (1976). Although the systemic possibilities for cohesive devices in the two languages are relatively similar, at least for the more general parts of the two systems, there are contrastive differences as well. The most important of these will be mentioned in the next section. Where such non-matching systems exist, they will show up in one-sided occurrences in the data: demonstrative pronominal adverbs (deictics) or demonstrative articles are rare or non-existent in our English data, for example, whereas verbal substitution and general nouns are very infrequent in our German data. In our lists of cohesive categories for the two languages, though, we are aiming at comprehensiveness – so no categories were excluded if they are specific to only one of the two language systems. Table 1 gives an overview of the categories of cohesion and their realizational types annotated in the corpus:

| Categories of cohesion | Realizational types |

| coreference | personal head, personal modifier, demonstrative head, demonstrative modifier, demonstrative local, demonstrative temporal, pronominal adverbs, definite articles |

| coreference chain | number of antecedents, number of anaphors, number of chains, chain length |

| comparative reference | comparative general, comparative particular |

| substitution | nominal, verbal, clausal |

| ellipsis | nominal, verbal, clausal |

| conjunctive relations | additive connects, additive adverbials, adversative connects, adversative adverbials, causal connects, causal adverbials, temporal adverbials, modal adverbials |

| lexical cohesion | general nouns |

Our categories of cohesion are thus language specific, but comprehensive for the two languages. There is no assumption that they would form the tertium comparationis or the basis for a definition of translational equivalence. The semantic relationships encoded by these devices would be better candidates, but even they are not necessarily preserved in translations, as our examples in this section demonstrate. However, the bases for comparison here are not the systems, but rather textual frequencies of occurrences by language, register, and by the generalized written vs. spoken modes, even where the systems are similar or identical.

2.2Systemic differences and some associated tendencies of instantiation

In the area of personal coreference (cf. Kunz and Steiner 2012), we find marginally more systemic distinctions in German overall (encoding of social distance in forms of address). In addition to distinctions in terms of lexical base forms, the encoding in German of grammatical as opposed to natural gender influences local resolvability of antecedent-anaphor chains with 3rd person singular pronouns differently from English; cf. examples (16) and (17) below.

(16)Denn Erhards Philosophie war nicht einfach ein singulärer Geistesblitz – sie stand in einer langen deutschen Tradition des Bemühens um das Glück der großen Zahl. [GO_ESSAY]

(17)For Erhard’s philosophy was not just a singular flash of inspiration – it was part of a long German tradition of seeking the happiness of the majority.

[ETRANS_ESSAY]

The English it in (17) may have either the subject or the subject complement as antecedent of the preceding clause, although the syntactic parallelism strongly suggests the former. The German sie in (16), by contrast, does not have any potential ambiguity.

Even where the systemic options for cohesive reference coincide, we find frequent alternative use of demonstrative reference in German as in examples (1, 2) above. Finally, there is frequent use of cohesive substitution, ellipsis, or lexical cohesion combined with reference devices (articles, demonstratives) for the encoding of coreference as a semantic relation.

In the area of demonstrative coreference, German has a diversified system of demonstratives for all the major referents and relations, including ‘demonstrative deictics’ (darüber, damit, dabei etc.). For many of these, it also has asserting vs. questioning (darüber vs. worüber) and near vs. far (darüber vs. hierüber) variants. There are also semantic and/or registerial differences between analytic and synthetic variants in particular (darüber vs. über das vs. da rüber). In terms of instantiation, German demonstratives serving as anaphors to complex antecedents may be preferred to personal it in English and es in German (as in examples 1 and 2 above). Finally, the English proximity-distinction between this/that may be more systematic and frequent than its German counterparts.

Comparing substitution in English and German (Kunz and Steiner 2013), we find that nominal and verbal forms are less grammaticalized in German, i.e. retaining more of their lexical meanings (ein(e,r,s), tun, so) than those of English. Clausal substitution relies on etymologically related forms in the two languages, but with differing meaning relations. Generally in the area of substitution there are more forms in German at the borderline to other cohesive types (comparative reference, conjunction) than in English, and they may exhibit multifunctionality in both languages, though in different ways, as in the case of so (König 2015). This is illustrated in (18) and (19) below:

(18)He thought he recognised the twisted thorn trees, and might indeed have done so. [EO_FICTION]

(19)Es wollte ihm scheinen, als erkenne er die krummen Weißdornbäume wieder, und das mochte sich durchaus so verhalten [. . .] [GTRANS_FICTION]

The English verbal substitution in (18) is translated as a combination of demonstrative reference (das), comparative reference (so), and a general verb (verhalten). The German so, classified here as comparative reference because of its remaining “manner”-meaning, is on the borderline between reference and substitution. The cohesive effect of (19) is similar to the one in (18), but the cohesive devices are different.

Comparing conjunction in English and German (cf. Kunz and Lapshinova-Koltunski 2014), we find a richer inventory in German (pronominal adverbs/demonstrative deictics) encoding fine-grained distinctions of meanings. For these and other distinctions, we find more multi-word constructions in English, for example use of English that is why for German deshalb. Because of the generally freer word order of German, there is more positional flexibility in German for the encoding devices, such as deshalb, which may occur in clause initial or clause-internal position. Additionally, more of the systemically available forms in German are at the borderline to reference and substitution, a possible overall indicator of a high multifunctionality of cohesive devices in German. Deshalb is a combination of demonstrative des- and logically conjunctive halb (like therefore in English), and German dabei in its adversative meaning is a combination demonstrative da with a preposition bei, fusing into an overall adversative conjunctive relation expression.

Moving onwards to ellipsis (cf. Menzel 2014), we first note the systemic possibility of ellipsis remnants with morphological agreement suffix to license elided nouns in German in the domain of NPs (21). In English, this possibility is very rare, hence the classification of ‘one/s’ as substitution in (20).

(20)People who need this science, I would make an effort to tell them we have real sciences, hard sciences, we don’t need imaginary ones. [EO_FICTION]

(21)Den Leuten, die diese Wissenschaft brauchen, also, ich würde mir extra Mühe geben, ihnen zu erzählen, daß wir richtige Wissenschaften haben, hieb- und stichfeste Wissenschaften, wir brauchen keine imaginäre (0). [GTRANS_FICTION]

German cases of ellipsis are on the borderline to substitution, if the ellipsis remnant can be analysed either as a pronoun replacing the noun or as a determiner in an incomplete phrase. This is the case if its inflectional paradigm allows the insertion of a supposedly elided head noun only after certain agreement suffixes (eine, keine (0) vs. eines,r keines,r (/) (one, none)). In the domain of VPs, we find more possibilities for omission of lexical verbs after operator/modal verbs in English. In the domain of the clause and its constituents, there are more possibilities for fragment clauses in German. There are probably more possibilities for true fragments in German altogether because of less ambiguity due to morphological markers. Those true fragments do not necessarily have underlying sentential structures that were subject to deletion/omission; therefore they will not be subsumed under the category of cohesive ellipsis. Exophoric or situational ellipses refer to the extralinguistic context and do not fall under the category of cohesive ellipsis in our annotation either.

The area of lexical cohesion is currently under investigation and receives little coverage in our chapter here. We do give a preliminary analysis of the distribution of general nouns, yet in conjunction with referential modification (these, such etc.) where necessary.

3Methodology

3.1Corpus Resources

For the corpus-based analysis of instantiations of cohesive categories we envisage here, we use GECCo, a German-English corpus containing written and spoken texts (cf. Lapshinova-Koltunski et al. 2012). The whole corpus contains ca. 1.3 million tokens and six subcorpora: English and German originals and their translations (extracted from CroCo; Hansen-Schirra et al. 2012), as well as two spoken subcorpora: German written originals (GO), English written originals (EO), English spoken originals (EO-SPOKEN) and German spoken originals (GO-SPOKEN), translations of German written originals into English (ETRANS) and translations of English written originals into German (GTRANS).74 The two written subcorpora (EO and GO) consist of texts from eight registers: popular-scientific texts (POPSCI), tourism leaflets (TOU), prepared speeches (SPEECH), political essays (ESSAYS), fictional texts (FICTION), corporate communication (SHARE), instruction manuals (INSTR) and corporate websites (WEB). The two spoken subcorpora contain academic speeches (ACADEMIC) and interviews (INTERVIEW). This text collection provides 20 subcorpora (the size of the subcorpora are given in Table 3, see section 4.1 below) which serve as variables for our corpus-based statistical analysis.

To extract frequency information on the occurrence of cohesive categories under analysis in these subcorpora, we deploy annotations available in GECCo. They include information on tokens, lemmas, morpho-syntactic features (e.g. case, number), parts-of-speech, grammatical chunks along with their syntactic functions, clauses, and sentence boundaries. The annotation of the written sub-corpora was partly imported from CroCo, whereas for the spoken part, we use the Stanford POS Tagger (Toutanova et al. 2003) and the Stanford Parser (Klein and Manning 2003). The corpus is encoded in the CWB format (CWB 2010) and can be queried with Corpus Query Processor (CQP; Evert 2005). The described annotation levels provide us with additional information on cohesive types, i.e. for coreference or conjunctive relations: morpho-syntactic preferences of antecedents and anaphors, position of coordinating conjunctions and conjunctive adverbials in a clause, etc. Information on cohesive devices and their categories is also annotated in the corpus, and includes both functional and structural subtypes of coreference, conjunction, substitution, ellipsis and lexical cohesion, as outlined in Table 1 in section 2. For reference chains, our annotations provide us with the information on the number of antecedents, anaphors, chains, as well as chain length.

For the annotation of cohesive categories, semi-automatic procedures were applied, which include a rule-based tagging of cohesive candidates and their manual post-correction by humans. The procedures involve an iterative extraction-annotation process based on the method derived from the system used for the YAC chunker (see Kermes and Evert 2002; Kermes 2003). The system is based on the option of the CWB tools to incrementally enhance corpus annotations, as query results deliver not only concordances of the searched structures but also information on their corpus positions. This permits the importation of information on queried data back into the corpus. In this way, we annotate candidates for cohesive categories, which are then corrected manually by human annotators with the help of MMAX2 (Müller and Strube 2006), as visualization options of this tool allow annotators to decide whether the candidates tagged by the automatic procedures have a cohesive function and belong to the given category. Moreover, in instantiations of cohesive relations, the borderlines between their categories may be blurred, e.g. the same realizational form (e.g. English or German so) may serve as different cohesive devices, depending on the context in which it is realized, see examples (18) and (19). These ambiguities can be resolved in the course of manual correction.

Manual procedures are also used for annotation of coreference chains, as human annotators manually identify antecedents and link them to the cohesive referring expressions (anaphors) which were automatically tagged by our system. A detailed description of the semi-automatic procedures of coreference, substitution and conjunctive relations is given in Lapshinova-Koltunski and Kunz (2014).

The instantiations of the categories given in Table 1 above can be easily extracted from the corpus, as relevant information is annotated and can be queried with CQP. Table 2 contains examples of queries used for data extraction.

Table 2: Query examples used to extract the categories under analysis

| Query | Explanation | |

| 1 | [_.mention_chain_id="set.*"& .mention_antecedent="none"] |

element in a reference chain & does not have an antecedent, an antecedent itself |

| 2 | [_.mention_chain_id="set.*"& .mention_antecedent!="none"] |

element in a reference chain & an anaphor has an antecedent |

| 3 | [_.mention_func="poss.*"] | personal reference with a modifying function (pers_mod) |

| 4 | [_.mention_func="temporal"] | temporal demonstrative reference (dem_temporal) |

| 5 | [_.mention_chain_id="set.*"] & post-processing |

all reference chains (nr_of_chains) |

| 6 | [_.conj_func="additive" & _.conj_type="connect"] |

additive coordinating conjunctions (additive_connect) |

| 7 | [_.conj_func="additive" & _.conj_type="adverbial"] |

additive adverbials (additive_adverbial) |

| 8 | [_.substitution_type="verbal"] | all cases of verbal substitution |

| 9 | [_.ellipsis_type="clausal"] | all cases of clausal ellipsis |

| 10 | [_.noun_type="general"] | general nouns |

For instance, query 1 is used to extract information on the number of antecedents in cohesive chains, query 2 to extract the number of referring expressions in cohesive chains. With the help of query 3, we can identify how many referring expressions function as personal modifiers, whereas query 4 is used to identify all cases of cohesive demonstrative reference with a temporal function. Query 5 is enhanced with a post-processing procedure to count chains which have the same ID (chain_id) per text. Queries 6 and 7 are built to differentiate between coordinating conjunctions and adverbials expressing additive relations. We apply queries like in 8 and 9 to extract different types of substitution and ellipsis, and query 10 is used to extract occurrences of general nouns. The extracted numeric results are saved in tables for statistical validation which is described in the analysis presented in section 4 below.

3.2Statistical methods applied

As already mentioned in section 1, we aim to analyse contrasts between languages and registers. This will help us to identify those phenomena that are relevant for translation analysis in terms of the four research questions raised in the introduction.

To answer these questions, we apply different types of quantitative analysis. We use descriptive data analysis to obtain information on the frequency of cohesive devices and in terms of distributions of main cohesive types. The findings provide a basis for interpretations in terms of research question (1) and also partially for question (3). In order to interpret our results with respect to questions (2), (3) and (4), we use explorative techniques, viz. correspondence analysis (CA; Venables and Smith 2010; Baayen 2008; Greenacre 2010), and supervised techniques, i.e. classification with support vector machines (SVM; Vapnik and Chervonenkis 1974; Joachims 1998).

3.2.1Descriptive data analysis

Descriptive data analyses are employed for two purposes: First, for the investigation of general frequencies, we relate the total number of cohesive devices to the total number of tokens per corpus and subcorpus. The results are tested for significance using the Pearson’s chi-squared test. Second, relating the frequencies of main cohesive features to the total number of cohesive features per corpus and subcorpus, we obtain insight into distributions of main cohesive types.

3.2.2Correspondence analysis (CA)

Correspondence analysis allows us to see which variables (e.g. languages or registers) have similarities and which differ from each other. Moreover, we are able to trace the interplay of categories of the cohesive devices under analysis. Some of the independent variables defined in our corpus (e.g. English and German) lead to clearly distinguished classes in terms of the exploratory technique of CA, while others (e.g. registers) are less well distinguishable than with text classification (with support vector machines, see below).

An input for CA is a table of numeric data, in our case frequencies of the categories under analysis across registers and languages (subcorpora). First, distances (differences) between rows, and distances between columns are calculated. In a second step, these distances are represented in a low-dimensional map (we use a two-dimensional map for the representation). The larger the differences between subcorpora, the further apart these subcorpora are on the map. Likewise, dissimilar categories of cohesive devices are further apart. Proximity between columns and rows (subcorpora and cohesive devices) in the merged map is as good an approximation as possible of the correlation between them.

In computing this low-dimensional approximation, correspondence analysis transforms the correlations between rows and columns of our table into a set of uncorrelated variables, called principal axes or dimensions. These dimensions are computed in such a way that any subset of k dimensions accounts for as much variation as possible in one dimension, the first two principal axes account for as much variation as possible in two dimensions, and so on. In this way, we can identify new meaningful underlying variables, which ideally correlate with such variables as language or register, indicating the reasons for the similarities or differences between these subcorpora. The degree of the contribution of a certain dimension to the plot will show where the greatest differences lie.

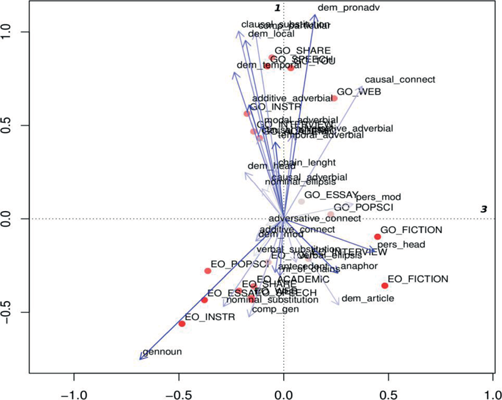

The ca package (cf. Nenadic and Greenacre 2007) is used to perform correspondence analysis in the R environment (cf. Venables and Smith 2010). The output of the correspondence analysis is plotted into a two dimensional graph. The length of the arrows indicates how pronounced a cohesive device is for the overall analysis, see Jenset and McGillivray (2012) for details. The position of the points in relation to the arrows indicates the relative importance of a cohesive device for a subcorpus. The arrows pointing in the direction of an axis indicate a high correlation with the respective dimension, and thus, a high contribution of the feature to this dimension, see Figure 2 in section 4.2 below.

3.2.3Support vector machines (SVM)

We use text classification with SVM to observe more fine-grained differences between the two languages (English and German) and the registers with respect to the features analysed. The major difference to CA is that with SVM (a supervised method) we impose the variables (language, register) on the data (rather than getting possible variables represented by the dimensions from the CA, an unsupervised method). Thus, while CA helps to get an overview of whether the features under analysis really reflect the variables that one wants to consider, with SVM, as we impose the variables, we can inspect in detail the whole range of features that make the variables distinct from one another. With SVM texts are classified according to the respective variables which are represented as classes. The classes defined in our corpus and used for classification are: (1) the languages, i.e. English and German, and (2) the registers shown in Table 3, again for each language, with particular consideration of the mode-dimension in some cases. The most distinctive features are drawn by the observation of how well they contribute to the distinction of specific classes.

Text classification tasks have been widely used, mostly based on bag-of-words representations (see e.g. Fox et al. 2012; Joachims 1998), where documents are represented by the words occurring in them. Other studies have used linguistic features generated out of linguistic theories (e.g. Argamon et al. 2008; Degaetano-Ortlieb et al. 2014), where the documents are represented by the occurrences of linguistic features rather than the occurrences of all words. In our approach, we use linguistic features based on cohesion.

For classification, we use support vector machines (SVM; Vapnik and Chervonenkis 1974), as they are known to obtain very good results on many relevant features (see Joachims 1998; Manning et al. 2008). In principle, SVM performs a binary classification trying to separate two classes from each other. As we have to solve a multi-class problem, we use a pairwise classification, i.e. one-versus-one classifiers are built. Considering the register distinction, for example, a classifier is built for each register pair (EO_ACADEMIC vs. EO_ INTERVIEW, EO_ACADEMIC vs. EO_ESSAY, etc.). Classification is performed with the data mining platform Weka (Witten et al. 2011). As a dataset, we use a matrix of linguistic features per text for each class. For interpretation, we consider the classification accuracy (overall and for each class) as well as the F-Measure, i.e. the harmonic mean or weighted average of Precision and Recall (Powers 2011; Van Rijsbergen 1979). Additionally, we inspect the SVM weights. The higher the weight of a feature, the more distinctive it is for a particular class, regardless of its positive or negative sign, which only indicates the class it belongs to.

In the analysis, we perform two classifications according to the distinction of language and register, analysing which cohesive categories and features contribute most to the distinctions.

4Quantitative analyses of English and German

4.1Descriptive data analysis

We start with a comparison of frequency distributions, which allow interpretations in terms of the overall degree of cohesion, our research question (1).

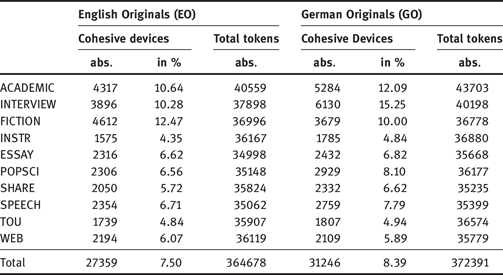

The total number of cohesive devices per register and per language (see TOTAL, last row) is presented in Table 3. It also provides information on the total number of tokens per text register as well as the distribution in percentage of cohesive devices in relation to the total number of tokens.

Table 3: Cohesive devices across languages and registers

Table 4 illustrates whether the contrasts between main corpora EO and GO (see ALL in last row), and contrasts per register between languages are significant, using Pearson’s chi-squared test. A p-value below 0.05 shows significant differences (+) between the languages and the registers of each language. In case the p-value is above 0.05, differences are not significant (–).

Table 4: Cohesive devices across languages and registers: results of the chi-squared tests

| EO ⇔ GO | p-value | Significance |

| ACADEMIC | < .0001 | + |

| INTERVIEW | < .0001 | + |

| FICTION | < .0001 | + |

| INSTR | < .003 | + |

| ESSAY | > .05 | – |

| POPSCI | < .0001 | + |

| SHARE | < .0001 | + |

| SPEECH | < .0001 | + |

| TOU | > .05 | – |

| WEB | > .05 | – |

| All | < .0001 | + |

Considering the results in Table 3, there is only a slight difference in the distributions in percentage between the main corpora EO and GO (TOTAL), i.e. all registers per language taken together. However, as the results from the Pearson’s chi squared test in Table 4 illustrate, the contrast between languages is significant as the p-value is below 0.05. Furthermore, we note variation if we compare the findings for each language per register: Table 3 illustrates that equally low distributions are found in both languages for the registers INSTR, WEB, TOU, ESSAY. Here the contrasts are not significant, except for INSTR, where the contrast is slightly significant (see Table 4). The distributions in the register SPEECH and SHARE are also rather low; differences between the languages are slightly significant. The contrasts for the registers POPSCI, FICTION, INTERVIEW and ACADEMIC are highly significant; while the amount of cohesive devices in POPSCI are somewhat in the middle in both languages, frequencies for FICTION and the two spoken registers are the highest of all registers in both languages. With some exceptions, language contrasts between written registers (hence translation relevant registers) are generally less pronounced than in the spoken registers. The greatest differences are attested for the register INTERVIEW, where we note a distribution of 10.28% cohesive devices in relation to all tokens in English and 15.25% in German. The register of FICTION stands out as it is the only register in which the frequencies in German (10.00%) clearly lie below those in English (12.47%). Quite interestingly, there is considerable variation across registers, language internally. The differences between registers in German are more pronounced than in English, ranging from 4.84% in INSTR to 15.25% in INTERVIEW (compare English, ranging from 4.35% in INSTR to 12.47% in FICTION). More variation in the degree of cohesiveness is therefore observed between registers in German than English, and between written and spoken registers, in particular.

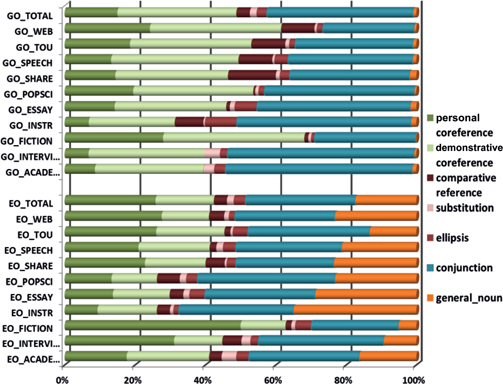

Figure 1 illustrates the distributions of cohesive devices signalling the main types of cohesion of all cohesive devices per register and per language. The findings are taken as a basis of interpretation (together with the analyses in sections 4.2 and 4.3 below) for research questions (2) to (4). The types shown in Figure 1 are personal and demonstrative coreference, comparative reference (comparison particular and general taken together), substitution (nominal, verbal and clausal taken together), ellipsis (nominal, verbal and clausal taken together), conjunction (additive, adversative, temporal, causal and modal) and general nouns (as the one type of lexical cohesion analysed in this study).

Figure 1 reveals general tendencies in the distribution of meaning relations (research question (3): we note a strong preference for relations of coreference and conjunctive relations in both languages. Most cross-linguistic similarities are observed for the register of FICTION, where we find the highest amount of coreference relations and lowest distributions for conjunctive relations. Apart from that, the amount of conjunctive relations is clearly higher and the amount of indicators of coreference slightly lower in German than English. All registers in German favour demonstratives for realizing coreference relations over personal reference, whereas the opposite is the case for most English registers. Comparative reference is preferred in five registers of German for realizing type-reference/comparison over substitution and ellipsis while English exhibits more even distributions. We observe a rather high amount of general nouns in English whereas this category can almost be neglected in German. German spoken registers are characterized by very high frequencies of conjunctive relations and demonstratives and higher distributions of substitution than other German registers. The differences between English registers altogether seem to be less pronounced than between German registers. Evidence for this tendency will be further provided with the analyses in sections 4.2 and 4.3.

4.2Exploratory analysis

We go on with correspondence analysis as presented in 3.2.2 above, which allows us to see which subcorpora have commonalities and which differ significantly from each other, so that we are able to detect where the biggest differences and similarities lie in the use of cohesive devices. Moreover, it provides us with information on the interplay of cohesive categories, and we can see which cohesive relations are generally preferred over others, as well as how much cohesive variation there is in different languages and registers.

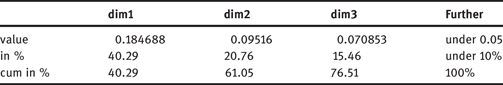

We use frequencies of the cohesive categories in different subcorpora to calculate distances (see section 3.2.2). In the first step, we determine how many dimensions are needed to represent and interpret our data. For this, principal inertias of dimensions (eigenvalues) are analysed.

Table 5: Principal inertias of dimensions

We can see from Table 5 that the first two dimensions (dim 2) can explain only 61.05% of the inertia. This means that some profiles (combinations of subcorpora) would lie more along the third or fourth axis etc., which are not visualized on a two-dimensional graph. However, we need to include the third dimension into our analysis to get a cumulative value of 76.51%, which is a satisfying coverage. So, we use two figures to represent the results in a two-dimensional map (Figures 2 and 3).

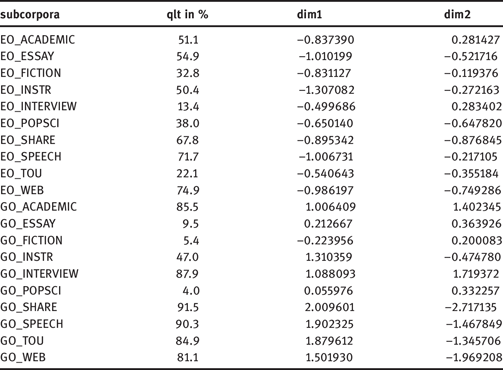

Figure 2 shows a graph representing the first two dimensions. Concerning dimension 1, we see a clear distinction between English and German subcorpora (along the x-axis on the left and on the right from zero respectively), with the exception of GO-FICTION, which is represented on the left side of the plot. However, GO-FICTION is not clearly visible on the graph, which is also seen in Table 6 illustrating χ2-distance (distances calculated on the basis of rows and columns, see section 3.2.1 above) to the centroid (dim1 and dim2) as well as the quality of display (qlt) of a variable in the graph (which amounts to only 5.4% for GO-FICTION). GO_ESSAY and GO_POPSCI have also very low values (their quality is <10%), although situated on the right (German) side of the axis. Thus, the higher the quality the better the subcorpora are represented by dimension 1 and 2, while the lower the quality the less representative these two dimensions are for the respective subcorpora.

We assume that the distinction along the first dimension (x-axis) reflects language contrasts in the use of particular cohesive features. Focusing on the features, cohesive devices on the right side are specific for German, whereas those on the left side are specific for English. Note that the three subcorpora with a lower quality of display, i.e. which are weakly represented in the first dimension, show distinction on the basis of register specific- rather than language-specific cohesive features, and therefore, should not be considered for the analysis of language contrasts. This assumption is confirmed by the results from text classification (see section 4.1.2), which show that German political essays, fictional texts and popular-scientific articles differ more strongly from the other registers in German. These three registers should be excluded also from the interpretation along the second dimension (y-axis), where we note a separation between written and spoken registers, as both English and German INTERVIEW and ACADEMIC subcorpora (representing the spoken registers) are situated above the zero, while the written subcorpora are situated below.

The graph also provides us with information on the relevance of cohesive features contributing to the separation along both dimensions by considering the direction of the arrow. The arrows pointing to the right (such as additive, adversative, temporal conjunctive relations) and to the left (substitution and lexical cohesion), contribute more to the distinction between languages, whereas those pointing up and down, such as coreference devices (especially personal subtypes) and features of coreference chains (expressed in chain length and number of chains75) contribute rather to the distinction between written and spoken registers. Some arrows are situated in the middle of the field, e.g. those of clausal substitution or comparative reference. This means that they contribute to the two distinctions observed.

Table 6: CA numerical results for the first two dimensions

Differences can also be seen in terms of cohesive variation in both languages with regard to both cohesive features and registers within languages. English registers seem to be more alike, as the distances between their points are shorter than those between German registers. The same tendency can be stated for the arrows indicating cohesive features – those specific for English.

To compensate the under-representation of the data (61.1%, see again Table 5), we add the third dimension, which allows us to increase the quality of subcorpora display, see Table 7. Particularly, the representation of GO-FICTION increases rapidly (from 5.4% to 88.4%).

Table 7: Numeric data for the third dimension and quality in the three-dimensional representation

| register | qlt | dim3 |

| EO_ACADEMIC | 58.7 | –0.537025 |

| EO_ESSAY | 91.6 | –1.421468 |

| EO_FICTION | 91.9 | 1.812896 |

| EO_INSTR | 87.2 | –1.824372 |

| EO_INTERVIEW | 17.0 | 0.446020 |

| EO_POPSCI | 80.1 | –1.360351 |

| EO_SHARE | 81.7 | –0.800174 |

| EO_SPEECH | 80.2 | –0.565533 |

| EO_TOU | 24.0 | –0.279389 |

| EO_WEB | 82.5 | –0.577310 |

| GO_ACADEMIC | 88.5 | –0.433591 |

| GO_ESSAY | 12.7 | 0.318894 |

| GO_FICTION | 88.4 | 1.683101 |

| GO_INSTR | 51.3 | –0.657484 |

| GO_INTERVIEW | 91.5 | –0.537037 |

| GO_POPSCI | 22.0 | 0.845048 |

| GO_SHARE | 91.7 | –0.213742 |

| GO_SPEECH | 90.9 | –0.294369 |

| GO_TOU | 85.0 | 0.126993 |

| GO_WEB | 87.1 | 0.903294 |

In Figure 3, we plot the third dimension in a two-dimensional graph (together with dimension 1). We suggest that the separation along this dimension shows which registers show similarities (independently from the languages), and which cohesive features contribute to these similarities. For example, we can clearly see this for ACADEMIC, FICTION, SPEECH and SHARE, whereas other registers (ESSAY, INTERVIEW, POPSCI, TOU and WEB) seem to be rather language-dependent. Moreover, the plot allows us to identify cohesive features contributing to these similarities. In our case, these are especially fictional texts with (personal) reference as a feature that makes them similar.

By the results of the correspondence analysis, we see that the first dimension represents the variable of language, and thus shows us where the differences between languages lie. The second dimension represents the variable of mode, which groups registers according to written and spoken features. And finally, the third dimension is the one of registers – yet another confirmation of a widely-shared assumption (e.g. Biber 2014) that apart from language itself, the written-spoken and the narrative-non-narrative dimension are strong interlingual dimensions of register contrast.

Now, looking for an answer to the question, where the greatest differences lie, we look again at Table 5. The greatest differences lie between languages, as this dimension contributes ca. 40%, the two others in the ranking list are the dimensions related to registers (21% and ca. 16% respectively), which, to our opinion, comprise a considerable proportion.

Summing up, with the help of correspondence analysis we were able to see where the differences and similarities lie, observe the breadth of cohesive variation in both languages, as well as find out which cohesive features contribute to the distinction along these dimensions (language and register).

However, this analysis procedure does not allow us to precisely define which cohesive features are distinctive for the different subcorpora under analysis. Therefore, we use supervised classification techniques in the next step.

4.3Supervised analysis

For the supervised approach, we use support vector machines (SVM) as a text classification technique (see also section 3.2.3). The classes are defined beforehand on the basis of (1) the two languages (i.e. English and German), and (2) the registers represented in the GECCo corpus. In the analysis we perform two classifications, analysing which cohesive categories and features contribute most to the distinctions of language and register.

The classification by language achieves an overall accuracy of 98.96%. Table 8 shows that for both languages the accuracies as well as the F-measure are very high, i.e. the languages are quite well distinguished from one another. This matches the findings obtained by correspondence analysis (section 4.1.1).

Table 8: Accuracy and F-Measure for the language distinction

| language | accuracy in % | F-Measure |

| GO | 97.90 | 0.99 |

| EO | 100.00 | 0.99 |

Table 9 shows the top 10 most distinctive features for each language according to the cohesive category.76

Table 9: Top 10 features for German and English

For features of conjunctive relations, German typically uses conjunctive adverbials (temporal, adversative, modal, and additive) while English uses connects (additive, causal). In terms of coreference, German and English differ in the use of demonstrative reference (GO dem-pronadv, EO dem-temporal). Additionally, while German uses comparatives of the particular type, English uses comparatives of the general type. In terms of substitution, clausal substitution is typical for German and verbal substitution for English (see section 5 for examples).

In summary, German and English are quite well distinguished by cohesive features, showing the biggest differences in the preference of (a) conjunctive adverbials and demonstrative reference for German, and (b) temporal demonstratives, in particular, as well as verbal substitution and general nouns associated with lexical cohesion for English (see features in bold in Table 9).

For the classification of registers by cohesion features, we achieve an overall accuracy of 76.46%, which is clearly lower than for the distinction by language. Thus, registers show some differences, but are less well distinguishable from one another. This is again in line with the results of the correspondence analysis in section 4.2. However, while correspondence analysis is an unsupervised method, in text classification, which is a supervised method, we impose the classes (in this case the register classes), getting more insights into the distinction of registers and which features contribute best to this distinction.

Table 10 shows the registers for each language ranked by F-Measure. We observe that the spoken registers for both languages show relatively high F-Measures (0.92-1.0), being very well distinguished by cohesion features from the other registers. Considering the written registers, fiction is best distinguished from the other registers for both languages (F-Measure of 1 for German and 0.98 for English). Popular scientific texts (POPSCI) are also quite well distinguished, in particular for German (F-Measure of 0.96 for German and 0.80 for English). The other written registers are less well distinguished; most obviously when considering the F-Measure, even though they show relatively high accuracies (consider, e.g., GO_TOU with an accuracy of 86.20% but an F-Measure of 0.58).

Table 10: Accuracy and F-Measure for German and English registers (ranked by F-Measure)

Table 11: Top 5 distinctive features for all GO_ACAD binary classification pairs

Table 12: Top 5 distinctive features for all EO_ACAD binary classification pairs

In the following, as an example, we present in more detail the contribution of features for the German and English ACADEMIC register, as it shows the best classification results. Tables 11 and 12 show the top 5 distinctive features for GO_ACADEMIC and EO_ACADEMIC, respectively. Focusing on feature categories, we can see that features of conjunctive relations prevail for GO_ACADEMIC (see Table 11), while coreference features prevail for EO_ACADEMIC (see Table 12) in the top 5. By inspecting more closely the top 5 features across all register pairs of ACADEMIC and another register for each language, we can detect some more fine-grained differences.

Table 11 (boldfaced features) shows that GO_ACADEMIC is distinguished from the other registers by adverbial modal conjunctions (present in all pairs), verbal substitution (in 7 pairs), and adverbial additive conjunctions (in 6 pairs). Note that modal conjunctions are more distinctive than additive ones or verbal substitution by the sum of SVM weights of all pairs (compare 10.9, 5.0, and 4.9, respectively).

From Table 12, we can see that EO_ACADEMIC is distinguished by lexical cohesion (9 pairs, 8.2 weight), nominal substitution (9 pairs, 7.4 weight) as well as by demonstrative reference (dem-mod: 7 pairs, 5.5 weight; dem-head: 7 pairs, 4.6 weight) and to some extent by personal reference (8 pairs, 4.6 weight) (see section 5 for examples).

In summary, GO_ACADEMIC and EO_ACADEMIC are very well distinguished from the other registers. Moreover, they distinctively use different cohesive features, which clearly reflect the language differences, where conjunctive relations are mostly distinctive for German and coreference mostly for English.

5Interpretation of findings and implications for translation

In this final section, we attempt an overall interpretation of the statistical results that have been discussed in section 4 with respect to the four research questions addressed in the introduction (section 1). Our focus here is on identifying contrasts in cohesion in terms of three variables: language (English vs. German), mode of production (written vs. spoken) and register. As explained in section 1, the mode of production translation vs. original will not be foregrounded here in terms of translationese. Rather, we will take the contrastive interpretations for each research question as a starting point for suggestions with regard to preferred translation strategies, to some extent, also with a view to interpreting.

Let us begin with the first research question, which is concerned with contrasts in the degree of cohesion. As the discussion in section 1 suggests, this question does not consider the relation between different cohesive features (as our other research questions do), but relates these features to other textual ranks. Cohesive devices serve as explicit indicators of textual relations to other linguistic expressions, beyond the level of grammar. The degree of cohesion can be calculated if we take the frequencies of all cohesive devices together, and relate them to the total number of tokens, as presented in section 4.1, Tables 3 and 4. The frequencies show that although there are only moderate differences in the distributions, language contrast between the main corpora EO and GO (all registers per language taken together) is significant. Some assumptions in the literature, assuming a preference for more explicit strategies in German as compared to English77, which have been attested for lexicogrammar by other studies (e.g. Hawkins 1986), therefore seem to be corroborated for the level of cohesion. Even more pronounced contrasts surface if we compare language contrasts per register. While similar distributions (no significant contrasts) or slightly significant differences are found in both languages for most written registers, contrasts between English and German in the registers POPSCI, FICTION, INTERVIEW and ACADEMIC are highly significant – although the direction of the differences is not the same across the board (e.g. FICTION in Table 3). So except for the registers popular scientific and fictional texts, language contrasts between written registers (hence translation relevant registers) are less marked than in the spoken registers. Therefore, the general translation method in terms of degree of cohesion for translators would be to keep the overall number of cohesive devices at a similar level as in the source texts, or to slightly increase it when translating from English into German. Our data shows however, that language contrasts in these and all other registers exist in the features used for creating cohesion (see below). Marked differences for the popular science texts suggest that translators should use cohesive devices more extensively when translating scientific texts from English into German. This requires verification by integrating written academic texts into the corpus in the future. FICTION is one notable exception to the overall tendency as the frequencies in German are lower than those in English. Our analyses may have to be combined with qualitative studies in the future to see whether strategies for literary translations should differ from those applied to non-fictional and specialized texts. The information that the differences between registers are more pronounced in German than in English, (mostly due to the higher frequencies in the spoken registers than in the written registers) – might be relevant for interpreting. We assume that register variation in the degree of cohesion may even be more marked in German than English, when integrating data from more spoken registers.

The interpretation of data in terms of strength of relation is partially drawn from Figure 1, permitting a comparison of general distributions of cohesive forms, from correspondence analyses, as shown in Figures 2 and 3, and text classification as shown in table 9. One relevant aspect for this parameter is whether cohesive relations are indicated by explicit and specific vs. weakly specified cohesive devices. Devices of ellipsis and substitution generally are considered to create weaker semantic ties than reference and lexical cohesion not only because of structural reduction but also because the specific semantic relation between referents is often less clear. Stronger relations of identity are created by referential modifiers as these are combined with devices of lexical cohesion, vaguer and/or ambiguous relations are established by referential pronouns, and the neuter pronoun it, in particular. Moreover, demonstratives serve as focus lifters and therefore are more explicit than devices of personal reference. Stronger relations of comparison are created by comparative reference, vaguer relations by substitution and ellipsis. Conjunctive adverbials indicate logico-semantic relations more explicitly than coordinating conjunctions (connects) since they usually contain more information in terms of the specific meaning relations established. General nouns establish less explicit sense relations than other types of lexical cohesion, e.g. repetition.

The data evaluated so far points to considerable differences between English and German in the explicit creation of logico-semantic relations. German prefers usage of adverbials and English mainly employs coordinating conjunctions (compare examples 22 vs. 23).

(22)Aufgrund der veränderten Sicherheitslage konnte die Mannschaftsstärke um 40 Prozent reduziert werden. Außerdem wurden, [. . .], knapp 11000 ehemalige Soldaten der Nationalen Volksarmee der DDR in die nun gesamtdeutsche Bundeswehr integriert. [GO_ESSAY]

The new security situation made it possible to reduce personnel by 40 %. Furthermore, almost 11,000 former soldiers from the GDR’s National People’s Army (NVA), [. . .] , were integrated into the new all-German Bundeswehr. [ETRANS_ESSAY]

(23)Mr. Bush has time and again demonstrated his commitment to open trade. And he is determined to extend the benefits of open markets to the world’s poorer nations. [EO_ESSAY]

Distributions of ellipsis are equally low in both languages. Moreover, they do not belong to the top distinctive features and therefore are no indicators of variation in strength of relation, from the perspective of language contrast. We note, however, that German generally shows a higher tendency towards comparative reference than English (especially towards comparative particular) in the written registers, which points to a more explicit marking of relations of type reference. The fact that clausal substitution is a distinctive feature of German has to be interpreted against the background that comparative reference plays a greater role for the overall creation of type reference/comparison than substitution or ellipsis in German relative to English. In addition, German shows a preference for demonstratives, hence focusing devices, for creating identity of reference (see Figure 2). For instance, consider examples (1) and (2) above, where German favours a demonstrative pronoun (e.g. das) or a demonstrative deictic (e.g. damit) over the neuter pronoun It, which is vaguer with respect to the (scope) of the antecedent.

While individual types of demonstratives (local and temporal) are distinctive features for coreference in English, the overall distributions for demonstratives are lower in all registers, whereas distributions for the two types of personal reference are generally higher than in German.78 Hence, German seems to be more explicit with respect to the creation of identity of reference.

In English, we find a clear preference for general nouns. This may point to a tendency in English towards creating weak relations of similarity by lexical cohesion. Whether general nouns here are indeed an indicator of weak relations has to be seen when evaluating data about other types of cohesion such as synonymy, meronymy, etc.

So the overall assumption that German tends towards more explicit cohesive devices and thus creates semantically stronger relations seems to be confirmed along most dimensions in our data. The findings suggest that translators should use more explicit devices in their target texts than in the source texts when translating from English into German. For instance, additive or adversative connects should often be transferred to adverbials in translations. Demonstrative pronouns should be used more often instead of personal pronouns (e.g. dies/das instead of es/it) and demonstrative modifiers in combination with types of lexical cohesion such as synonymy more often than the definite article in combination with a general noun. And finally, comparative particular should occur more often than comparative general or substitution. Opposite strategies should be favoured when translating from German into English.

Furthermore, we observe a stronger variation in the strength of cohesive devices between German registers than English registers (see Figures 2 and 3). We note a preference for substitution pointing to weaker relations in spoken than written German, and also a very low distribution of comparative reference in GO_ACADEMIC and GO_INTERVIEW (see Figure 1). German spoken registers are also marked in the heavy use of demonstrative pronouns and a lower distribution of demonstrative modifiers (combined with lexical cohesion). This may correlate with a preference to summarize large textual passages but needs to be tested by examining the textual scope of coreferential antecedents. The tendency towards substitution and also elliptical constructions reflects weaker relations in spoken than written English. Hence altogether, we observe that there is a tendency in both languages for spoken registers to use more cohesive devices (as shown in Table 1) but at the same time these devices are less explicit than in the written registers. This again may be relevant information for interpreters and also translators, who additionally have to be aware of the fact that different features are responsible for the variation in mode in German as compared to English.