6

NEW KINGS, 1377–99

The war reopened in 1377 on an indecisive course. There was a new king, Richard II, on the English throne; a boy incapable of providing the leadership that Edward III had given. The government adopted a new strategy, that of the ‘barbicans’. Cherbourg was leased from Charles of Navarre in 1378, and Brest had been in English hands since 1342. These ports would give the English a good position to control the sea route to Gascony, and they would provide convenient bases from which their armies could operate. Calais and the Gascon ports were also seen as barbicans. The commons in parliament, dubious about the cost, were told, ‘if the barbicans are well guarded, and the sea safeguarded, the kingdom shall find itself well enough secure’.1 For the English, the war against the French was increasingly defensive, and increasingly expensive.

In 1378 there was a new element in the conflict, the papal schism. On the death of Gregory XI, the Roman candidate, Urban VI, was supported by the English. His rival at Avignon was Clement VII; he was backed by the French. The schism would continue to divide Europe until 1417; though there were no doctrinal differences between the two sides, a new dimension was added to dynastic and other conflicts.

Gascony was not given a high priority by the English in these years. James Sherborne calculated that the duchy received just 16 per cent of all of the funds spent on the war from 1369 to 1375, less than Calais with 29 per cent. It cost over £32,000 to send John of Gaunt to the duchy in 1370, returning in the next year, but after 1372 very little was spent on the defence of Gascony. In 1377 a major French offensive under the Duke of Anjou captured, among other places, Bergerac and Saint-Macaire. The chief English commander, Thomas Felton, was taken prisoner in a skirmish. Yet the English were not to be driven out of the duchy. A new royal lieutenant, John Neville, had considerable success in 1378. Real power in southwestern France, however, lay increasingly in the hands of Gaston Phoebus, count of Foix, and the counts of Armagnac. The Duke of Berry proved to be an ineffectual French royal lieutenant, and little was done to dislodge the English. Routier companies, many claiming some allegiance to the English, found the region a good hunting ground. The Duke of Bourbon, given command alongside Berry in 1385, had some notable successes; at the siege of Verteuil he fought hand-to-hand in the mine that his engineers had dug under the walls of the castle, and duly received its surrender.

In 1378 the parlement of Paris condemned the Duke of Brittany, John de Montfort, in his absence. The duchy was declared confiscated. There was much hostility in Brittany to this move, and when the duke returned there in 1379, he found widespread support. However, when an English fleet set sail for the duchy in December it was destroyed by a fierce storm. The commander, John Arundel, was drowned; Hugh Calveley clung to some rigging, and was blown ashore onto a beach. For the chronicler Walsingham, the disaster was hardly surprising, for before the fleet had sailed, Arundel had insisted on billeting many of his men in a convent, where they ‘subjected the nuns to their excesses, giving no thought to the infamy that would result from their sinful debauchery’.2

The year 1379 saw an extraordinary plan adopted, which suggests that some English ministers were living in a fantasy world. At Windsor the young Count of St Pol, who had been captured in 1374, met a seemingly adorable widow, Matilda Courtenay, half-sister to the king. His release was agreed on condition that he did homage to Richard II, held his castles for the English, and attacked the town and castle of Guise in Picardy. The plan failed dismally, but the count paid his ransom, and married Matilda. The wedding featured musicians and actors galore, but the chronicler Walsingham commented sourly that ‘it gave joy to few and advantage to nobody, and indeed most people were upset by it, and found it hateful’.3 The count would die at Agincourt.

A major loss for the French in 1380 was the death of du Guesclin, who fell ill at a siege in southern France. He was seen in his own lifetime as a chivalric hero par excellence, comparable with the Nine Worthies of legend, who included Charlemagne and King Arthur. He had been appointed Constable of France in 1370 in an acknowledgement of his military reputation. Until his death he was constantly active in French service against the English. His career, however, remains something of a puzzle. He experienced defeat as well as victory, and quite what it was that so impressed his contemporaries about his leadership abilities has been lost in the welter of adulation accorded him. For one French historian, Edouard Perroy, he was ‘a mediocre captain, incapable of winning a battle or being successful in a siege of any scope’, and was a man ‘swollen with self-importance’.4 He was, however, an inspirational leader, who had an excellent sense of strategy. It was not a matter of glorious battles, but one of rapid marches and surprise attacks in what was almost guerrilla warfare. Together with Olivier de Clisson, he transformed the course of the war.

Fig. 8: The tomb effigy of Bertrand du Guesclin, in the basilica of Saint-Denis

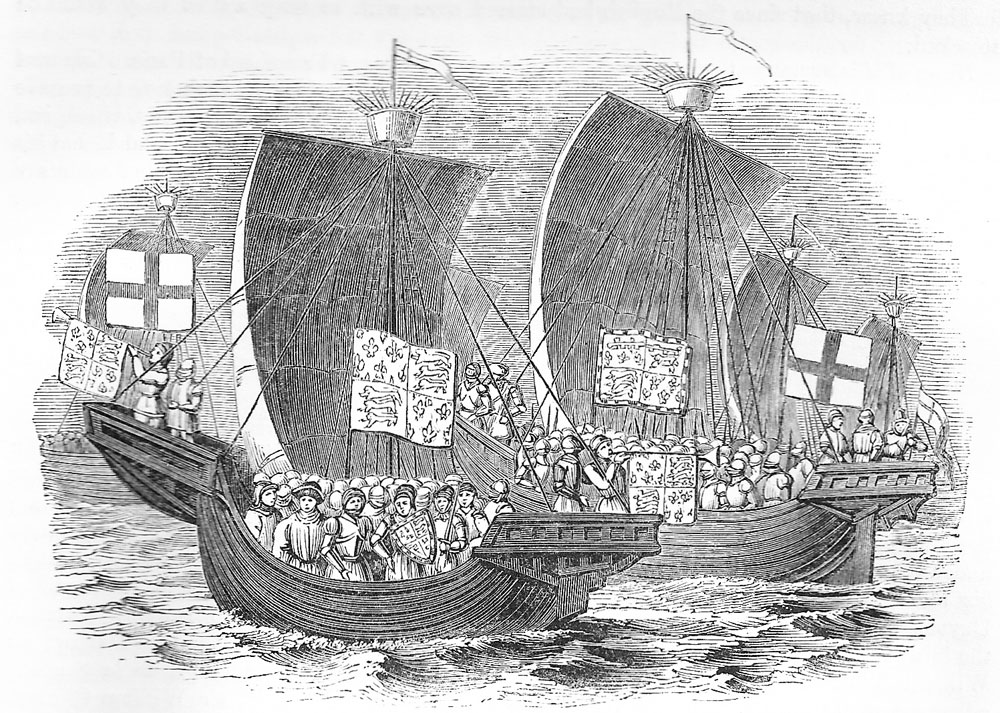

Fig. 9: The Earl of Buckingham crossing to Calais, 1380

The English had ambitious plans in 1380. Initially, it was hoped to send a substantial force to Brittany, but there were insufficient ships. Instead, the Earl of Buckingham set out from Calais towards Reims and then Troyes. This traditional English strategy of the chevauchée was no longer as effective as in the past. The Duke of Burgundy refused battle, and the army proceeded on its destructive course to Brittany. The French might have blocked its route, had it not been for the news of the death of Charles V.

The new king, Charles VI, was almost 12; like England, France faced the problems of an underage monarch. The war with England was of less concern than the situation in Flanders. The towns of Ghent, Bruges and Ypres had risen against the count in 1379. The Ghent militia known as the White Hoods led the way; in 1382, Philip van Artevelde, son of Jacob, emerged as leader and was victorious at Beverhoutsveld over the Bruges militia. There, an initial artillery barrage proved highly effective. Artevelde sought English support, but no worthwhile assistance was forthcoming, and at Roosebeke a large Franco-Burgundian army, its strategy and tactics masterminded by Olivier de Clisson, defeated the townsmen. Artevelde himself was slain. The Flemish artillery proved ineffective against well-organized cavalry attacks. The Duke of Bourbon’s biographer described the way his hero swung his axe left and right and ‘plunged amongst the Flemings, and fell to the ground and was wounded, but was soon rescued by the good knights and squires’.5 This was the first experience of battle for a future hero of chivalry, the 16-year-old Jean le Meingre, known as Boucicaut.

In 1383 English assistance to the Flemings finally arrived. It took an unusual form: Bishop Despenser of Norwich led an expedition which, taking advantage of the papal schism, took the form of a crusade supporting the claims of Urban VI against the supporters of Clement VII. Roosebeke had been a Clementist triumph. A crusade had advantages for recruitment, as Bishop Despenser could offer heavenly rewards: ‘It was even said that some of his commissaries asserted that angels would descend from the skies at their bidding.’6 His force did not lack experience; both Calveley and Knollys took part in the expedition. Initial success was deceptive. A siege of Ypres failed, and though a large French army did not engage Despenser in battle, the English lost all that they had taken at the start of the campaign. Despenser and three of his captains (though not Calveley or Knollys) were put on trial when they returned, thoroughly demoralized, to England. This dismal expedition to the continent was the last of Richard II’s reign.

THREATS OF INVASION

These years saw England threatened by invasion, to much alarm. In 1371 the Chancellor, William Wykeham, told parliament that the French were stronger than in the past and had a sufficient army to conquer all the English possessions. Their fleet was sufficient to destroy the English navy, and then invasion would follow. There proved to be justification for his warning. In 1377 a French fleet, which included Castilian and Portuguese ships, raided the south coast. Ports from Rye in the east to Plymouth in the west were assaulted. After returning to Harfleur for resupplying, the notable French admiral, Jean de Vienne, sacked much of the Isle of Wight in a second raid. In 1380 the French took Jersey and Guernsey, and Castilian galleys attacked Winchelsea and Gravesend. There was real panic right across the south coast.

Measures were taken to deal with the invasion threat. At Southampton over £1,700 was spent on a new tower, which was started in 1378. Some new castles were built, notably Bodiam and Cooling, both licensed in the 1380s, and built respectively by the veteran soldiers Edward Dalyngrigge and John Cobham. No doubt personal glorification was one motive, but a sense of patriotic duty should not be dismissed. There was a very real fear that the war that had so ravaged France would come to England.

The renewal of the conflict with France in 1369 had brought with it an inevitable renewal of the Franco-Scottish alliance. David II died in 1371 and was succeeded by Robert II, a Stewart. Cross-border raids, and the fact that some of David II’s ransom remained unpaid, were a cause of friction, but the truces largely held. In 1384, however, a small French force landed in Scotland, and joined in a raid into Northumberland. In the next year a larger French force of 1,300 men-at-arms and 300 crossbowmen sailed to Scotland in a fleet of some 180 ships. Orders were given for ‘four of the largest ships in the army’s fleet to be painted in a bright red colour, with the arms and emblems of Monseigneur Jean de Vienne, admiral of France’.7 There was justified concern ‘lest any riot or debate occur between any of the French and Scots’. Those who were disobedient were threatened: ‘if he is a man-at-arms he will lose horse and harness, and if he is a valet, he will lose his fist or ear’.8 Though the French reached Morpeth, well into Northumberland, the expedition ended in disarray, with bitter recriminations between the French and the Scots.

Meanwhile, Richard II had raised a large army of some 14,000 men. An old-fashioned feudal summons was employed, the first since 1327; there may have been a concern that if none was issued during the reign, the precedent would be entirely lost. Faced with a large-scale invasion, the Scots did as they had done in 1322, and simply pulled back, taking as much food away as they could. The English army reached Edinburgh, and, increasingly short of supplies, rapidly withdrew.

The next year, 1386, saw by far the most serious threat of invasion, when a huge Franco-Burgundian fleet and army assembled at Sluys. Preparations included the construction of ‘a palisade of marvellous contrivance, with towers and armaments, which they were to take with them, and which, wonderful to relate, could be assembled within three hours of their landing in England’.9 One French writer estimated that there were 16,000 ships, of which half were large vessels with two sails. No finer fleet and army, he thought, had been assembled since the siege of Troy.10 However, the winds were unfavourable, and the French army was diverted to recapture Damme, taken earlier in the year by the men of Ghent (with English assistance). The invasion of England was delayed and then abandoned when the weather turned in October, with contrary winds and torrential rain. This was a major turning point, for it was the closest that the French came to a large-scale invasion during the whole of the Hundred Years War. Had they managed a landing, they might well have succeeded in overthrowing Richard II’s weak and unpopular rule. English preparations saw some 4,500 men recruited, but such a force would have been quite inadequate in face of a French army which may have numbered as much as 30,000.

In the following year the English had a rare success. A large Franco-Flemish fleet had been loaded with wine at La Rochelle. In March the Earl of Arundel, with a fleet of some 60 ships, larger and better equipped, defeated the Franco-Flemish in a running battle, initially off Margate, and finally near Cadzand. The earl’s forces then engaged in a brief pillaging campaign, but were unable to follow their victory through. Arundel’s attentions were then directed to domestic politics; he was one of the Lords Appellant who attacked the king’s favourites in the Merciless Parliament of 1388.

The Scots continued to threaten; in 1388 they launched a double attack on the north, with one army in the east and one in the west. At Otterburn an English force under Henry Hotspur, son of the Earl of Northumberland, was routed, even though the leader of the outnumbered Scots, Douglas, was killed in the battle. In 1389 a truce was agreed, which lasted for the rest of the century.

POLITICS AND PEACE

After the failure of the planned invasion of England in 1386 there was little enthusiasm in France for a continuation of the war with England. In 1388 the young king Charles VI threw off the control exercised by his uncles, the dukes of Burgundy, Berry, Anjou and Bourbon. A group referred to sarcastically by their opponents as marmousets dominated government until 1392. These men were largely drawn from the middling nobility; Olivier de Clisson was among them. There were also some with bourgeois backgrounds. The marmousets had a clear, coherent and ambitious view of the nature of the state. A programme of reform was instituted, aimed at reducing administrative costs and taxes. Indirect taxes were reduced; the king should live off his own resources. Officials would be selected for their competence. However, when the king’s mental instability became all too clear, the king’s uncles moved against the marmousets. Clisson, who had survived an assassination attempt in the summer, was deprived of the office of Constable, and was fined 100,000 francs. Rather than renewing the war with England, the French became increasingly involved in the complex world of Italian politics. In 1396 the crisis-ridden city of Genoa decided to accept French rule. A further ambitious and difficult project was the crusade. In 1396 a large crusading army, largely drawn from France and including many veterans of the war with England, was crushed in the Balkans by the Turks at the Battle of Nicopolis.

The war, its expense and what was seen as its mismanagement provided the backdrop to the turbulent politics of this period in England. In 1376, in the Good Parliament, the commons had attacked the king’s ministers, and his mistress Alice Perrers. Accusations over the loss of Saint-Sauveur and Bécherel were directed at Lord Latimer and Thomas Catrington. Richard II faced the anger of the Lords Appellant (the Duke of Gloucester and the earls of Arundel, Warwick, Derby and Nottingham) in 1388 in the Merciless Parliament. Many of the king’s favourites and associates, notably the Duke of Suffolk, were summarily found guilty of treason. Suffolk escaped, but many were executed. Court intrigue, with an extreme dislike of Richard’s favourites, does much to explain the crisis, but it is also the case that the Appellants wished to see a far more aggressive policy taken in the war, rather than the appeasement favoured by the young king.

Peace with England was one of the objectives of the marmousets, and a truce was agreed in 1389, though a final agreement remained elusive. In 1390, Richard II granted Aquitaine to his uncle John of Gaunt, to hold from him in his claimed position as king of France. This has given rise to much argument among historians. John Palmer argued that this was a first step towards a peace settlement, in which Gaunt would hold Aquitaine from the French king. His views have attracted much revision.11 It is likely that this was among the many options discussed, but by 1393, with a different regime in control in France, the way forward was envisaged as agreeing on the one hand to settle the boundaries of English-held Aquitaine, and on the other, accepting that Richard would do liege homage to Charles VI. This, however, was unacceptable to the English parliament, and the peace process ground to a halt. In 1395, however, Richard married Charles VI’s daughter Isabella, aged just six. Relations between the two countries were now on a very different footing, and in the following year a 28-year truce was agreed.

FINANCING WAR

A peace policy made sense, for the costs of war were high in these years. Even though there was no great campaign on the scale of Edward III’s 1359 expedition in these years, military expenses following the renewal of hostilities in 1369 were very high. James Sherborne estimated that almost £1,100,000 was spent by 1381. Lancaster’s chevauchée in 1369 cost £75,000, and that of 1373 at least £82,000. The 1381 expedition brought expenses of about £82,000. The war at sea was costly: in 1373, naval expenses approached £40,000. Arundel’s expedition in 1387 was an exception, for it was relatively cheap, at about £18,000. It was also successful, with prizes and booty totalling about £16,500, a quarter of which went to the crown. Maintaining the Calais garrison, with associated expenses, cost £20,000 or more a year. Brest and Cherbourg, the barbicans, were also very expensive to maintain, at some £30,000 a year. In the years 1377 to 1381 about a third of English war expenditure was accounted for by these three ports.

The French also faced high costs, but ways were found to overcome the financial problems. In 1371, payment of officials’ salaries was halted, and with tax revenues declining, Charles V had to borrow 10,000 francs from a syndicate of Italian bankers. Yet by continuing to levy taxes initially imposed in order to pay for King John’s ransom, the position of Charles’s government improved, with receipts probably worth double those of the English crown. However, a major crisis over taxation began in 1380, when the dying king, aware of the possibility of rebellion, abolished the fouage, the hearth tax. His successor, Charles VI, was only 12. Popular pressure led to the promised abolition of all taxes introduced since the early fourteenth century. A request to the estates-general for new grants met with a hostile response, but it was agreed that regional assemblies should be approached. Grants were made, but these were insufficient, and when a general assembly conceded a sales tax of 12 pence in the pound, the townspeople ‘took no account of the ordinance, saying that if axes were used to compel them, they would never accept the decree without widespread slaughter’.12 There was a violent reaction in many towns to the demands. In Rouen a local merchant was proclaimed king of the city, promising the abolition of all taxes, but the rebellion was soon put down. Victory in Flanders at the Battle of Roosebeke in 1382 strengthened the crown’s position, and the traditional taxes were reimposed. In 1385 the familiar expedient of debasement of the coinage yielded substantial receipts, while a forced loan raised large sums. By 1390, French royal revenue was probably higher than at any other point of the Hundred Years War.13

For the English, the traditional means of raising revenue for war were no longer sufficient. It was not possible to raise loans on the imprudent scale of Edward III’s borrowings in the initial years of the war, and the parliamentary subsidies, the fifteenths and tenths, were inadequate, as were customs revenues. Even a grant of a double subsidy in 1377 was not enough. A tax levied on parishes in 1371 was granted specifically as a one-off. The calculations for this tax were seriously out of line, as the government assumed there were far more parishes than was the case. Poll taxes, of which three were levied, were introduced in 1377. As in France, unpopular taxation led to popular rebellion, for this was a major cause of the Peasants Revolt of 1381.

ITALY

The fragile peace established at Brétigny, and the English lack of success when the war was renewed in 1369, led some English soldiers to look elsewhere for fame and fortune. Italy was tormented by war, with complex rivalries between wealthy cities. These conflicts provided splendid opportunities for ambitious men schooled in the Anglo-French wars. By 1369, Florence had 33 English captains in its forces, employing a new formation, that of the lance, which consisted of two men-at-arms supported by a squire and backed up with archers.

The most notable of the English who fought in Italy was John Hawkwood, whose career there began in the early 1360s, when he was one those who, following the Treaty of Brétigny, continued to fight. He joined the mercenary White Company, commanded by a German, Albert Stertz. Nothing is known of Hawkwood’s experience in Edward III’s armies, but he clearly had an excellent knowledge of the arts of war. His first real success came in 1369 at Cascina, where he dismounted his men-at-arms in a manner familiar from the battlefields of France. His forces soon became known as the English Company; some of his men were drawn from his own home neighbourhood in Essex. Over the years he fought for Pisa, Milan, the kingdom of Naples and the papacy, but above all he served Florence, where he became captain-general in 1380. Hawkwood’s successes were many; one resounding triumph was at the Battle of Castagnaro in 1387, where he led forces from Padua against Verona. Dismounted cavalry, supported by archers, and a carefully chosen battle site were the key to victory, as had been the case at Crécy and elsewhere. In his final campaign, in 1391, Hawkwood succeeded in extricating the Florentine army when the Milanese appeared to have it at their mercy. It was his strategic and tactical awareness, his skilled surprise tactics and his use of intelligence that made Hawkwood such a notable commander. He was a loyal Englishman; both Edward III and Richard II employed him in their diplomacy in Italy, particularly in negotiations with Milan. There was no move, however, to employ him in the French war. Though Hawkwood sought a comfortable retirement in England, he died in 1394 before his planned return home, having lost most of the fortune he had won.

SPAIN AND PORTUGAL

One reason why the English were unsuccessful in the war with France in this period was the distraction provided by continuing ambitions in the Iberian Peninsula. John of Gaunt’s marriage to King Pedro’s daughter Constanza in 1371 gave him a claim to the kingdom of Castile. In the following year Edward recognized Gaunt as king of Castile. This was an obvious way to counter the French alliance with Enrique of Trastamara. It seems likely that the English optimistically hoped to detach Enrique from his alliance with France by withdrawing Gaunt’s claim, but Enrique was not to be moved. Gaunt’s alliance with the Portuguese ruler, Fernando I, came to nothing, nor did those with Aragon and Navarre. It was not until 1381 that an English force landed in the Peninsula. This was led by Gaunt’s brother Edmund of Langley, later duke of York, who was married to Constanza’s younger sister Isabel. The expedition was a failure. The English troops allegedly behaved disgracefully towards their allies, ‘killing and robbing and raping women, haughty and disdainful to all as if they were their mortal enemies’.14 Fernando made peace with Enrique’s son, Juan I, who had succeeded to the Castilian throne in 1379.

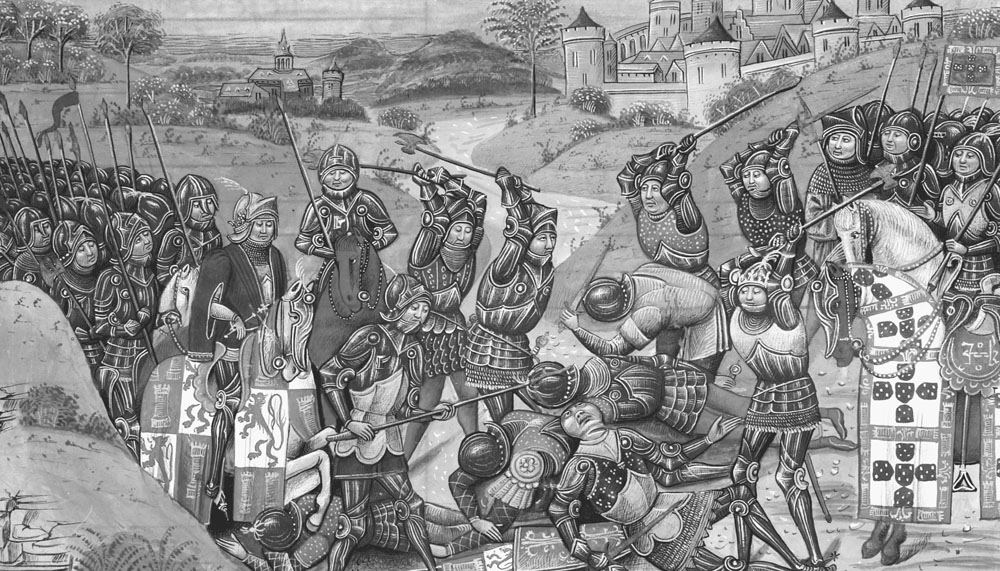

In parliament in 1383 the Bishop of Hereford compared the prospects for campaigning in Flanders or Portugal and declared of the latter that ‘there is no place on earth so likely to bring an end to the wars, swiftly and effectively concluding them, as is that place at present’.15 Before Fernando’s death in 1383, his queen had made an alliance with Juan of Castile, who married her daughter Beatriz. She was underage, and Juan took advantage of the situation to try to take over Portugal. A rebellion saw Fernando’s illegitimate half-brother João of Avis first become regent, and then king in 1385. He sought an alliance with England, and achieved a striking victory over Juan at Aljubarrota. There were probably about 700 English troops present, mainly archers, part of an army of some 12,000. The Portuguese organized their forces along English lines, with dismounted men-at-arms in the centre in two divisions one behind the other, and cavalry on the wings with archers placed behind them. Nuno Álvares Pereira, the Portuguese Constable, had argued for a battle, in contradiction to most of João’s council. The first position he chose was outflanked by the Castilians; the second proved ideal. The Castilian vanguard was decimated by archery and javelins; further attacks failed disastrously, though there was such alarm when the main Castilian division advanced that the order was given to kill the prisoners who had been taken, just as would happen at Agincourt. The argument was that ‘It is better to kill than to be killed, and if we do not kill them, they will free themselves while we are fighting, and then kill us. No one should trust their prisoners.’16 Eventually Juan fled, his army cut to pieces. Most battles in this period were not decisive; this one was, for it ensured the survival of the independent kingdom of Portugal.

Aljubarrota is particularly interesting because of the exceptional archaeological survivals, unique among battles of the Hundred Years War. Excavations revealed a defensive system of ditches and pits, clearly intended to protect infantry from cavalry attack. In many cases pebbles were found in them, which fits with chronicle evidence that the infantry hurled stones at the start of the battle. Bones from some 400 individuals were discovered, which show the horrific effects of battle, with many savage cuts to the head, and evidence of wounds from crossbow bolts and longbow arrows.17

Fig. 10: The Battle of Aljubarrota, 1385

Following the Portuguese victory, John of Gaunt’s claim to the kingdom of Castile looked more realistic. In parliament in 1385 the Chancellor ‘argued by a variety of reasons and examples that the best and safest defence of the said kingdom would be to conduct and wage fierce war on the enemies of the king and kingdom in foreign parts, since beyond doubt to await war on home soil would be most dangerous and greatly to be feared’.18 It was agreed that part of the taxes granted should go towards Gaunt’s expedition, though the sum involved was well short of what was needed. When he sailed in 1386 it was with a force probably numbering about 1,500 men-at-arms and 2,000 archers. He landed in A Coruña, and conquered Galicia with surprisingly little difficulty; Juan was not concerned to protect a remote province, nor was he willing to risk the battle that Gaunt was ready to offer. Gaunt’s position became more difficult in the following year. He was able to provide only limited assistance to the Portuguese invasion of Léon, and though Villalobos surrendered, the campaign was soon abandoned. Dysentery and desertion led to the disintegration of the English force. Juan’s position was strengthened by French reinforcements. Gaunt cut his losses, and negotiated terms with the Castilian ruler. Each would work for peace between England and France; Juan’s son would marry Gaunt’s daughter. Gaunt would give up his claim to the Castilian throne, and his conquests in Galicia, in return for substantial sums. In 1389, further negotiations, aimed at establishing both a permanent peace and the end of the papal schism, ended in failure. Gaunt’s involvement in Spanish affairs came to an inglorious end. His claim to the Castilian throne was extinguished, the Franco-Castilian alliance was not broken and the schism was not ended. Gaunt eventually died in 1399.

Richard II’s reign closed with his deposition in 1399, and his life ended, somewhat mysteriously, in 1400. A complex character, he had an exalted view of kingship, but lacked military ambition. ‘Fair-haired, with a pale complexion and a rounded, feminine face’ and ‘capricious in his behaviour’, he was considered ‘unlucky as well as faint-hearted in foreign warfare’.19 Among his disastrous miscalculations in his final years, the most serious was his decision to exile John of Gaunt’s heir, Henry Bolingbroke. Richard’s power base of a narrow clique of councillors proved totally inadequate. The war with France was not a major factor in the crisis that led to his deposition, but a treaty between Bolingbroke and the Duke of Orléans, drawn up in 1399, threatened the amicable relationship between Richard and the French government. It was from France that Bolingbroke set out, to land at Ravenspur. With the support of the powerful Percies in the north, he swept to power, facing virtually no resistance. With the advent of a new dynasty, that of Lancaster, the war would take a new course.