13

ARMIES IN THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY

The English faced new issues in the fifteenth century. Not only did they have to recruit expeditionary forces, but they also needed to find ways of providing effective defences for their possessions in France. Despite the pressures, there were no attempts to transform English armies. The methods that had served well in the past continued to be employed, against a background of financial difficulties and a lack of enthusiasm for an increasingly unsuccessful war. One major change came with Henry V’s death, for after that, with an underage king, the royal household ceased to play its central part in providing troops and organizing the military effort. In contrast to their rivals, the French made considerable efforts in the 1440s to reform their armies, with major ordinances setting out the principles on which well-organized and properly integrated armies should operate.

The largest force that Henry V led to Normandy was that of 1417, some 10,000 strong. However, expeditionary forces were subsequently much smaller, generally numbering under 2,000. There were exceptions: the Earl of Gloucester commanded about 7,500 men in 1436 when Calais was threatened. Beaufort led 4,500 in 1443, the largest force in the final decade of the war. In some cases, as with the Earl of Salisbury’s expedition of 1428, when he had about 2,700 men, the crown entered into a single indenture with the leader of an expedition, who would then make his own agreements with smaller companies. In others, separate indentures were made by the crown with the leaders of such companies; in 1430 there were 114 such contracts. This made no difference to the forces in the field, which were organized as ever into retinues of varying size. Regular musters took place, ensuring that the men were properly equipped, and that the terms of contracts were properly fulfilled.

Large numbers of men were employed on garrison service in Calais and in Normandy; it has been calculated that in 1436 there were almost 6,000. Recruitment followed the same pattern as for expeditionary forces. Contracts were made with individual captains, who then provided retinues. Evidence suggests that career soldiers might serve under a number of captains, in different retinues.1 Though there was no true standing army, garrisons provided an element of permanence. Men could be detached from garrison service so as to reinforce field armies. In addition, there were troops raised locally in Normandy. There, feudal summonses could in theory have raised 1,400 men, while general summonses of ‘all the nobles and other people who are accustomed to war’ were backed by threats that anyone who did not respond would be reputed to be ‘rebels and disobedient to the king our lord’.2

SUPPORT FOR THE WAR

There was a powerful tradition that the greatest men in the land would take a leading role in war. In 1436, eight dukes and earls, and 17 barons, served on the campaign to defend Calais. Thereafter the story was very different. In 1443 Somerset complained of the ‘lack of barons, bannerets and knights’ on his expedition.3 There was no aristocratic involvement at Formigny in 1450, and John Talbot, earl of Shrewsbury since 1442, had no earls or barons with him when he was defeated at Castillon in 1453, save his son, Viscount Lisle. The level of overall support for the war from the nobility was far from what it had been earlier.

Knightly involvement in the war also fell. An enquiry in Yorkshire in 1420, seeking the names of those prepared to serve Henry V in Normandy for wages, revealed a striking lack of enthusiasm for the war. Some were too old. Poverty was the most common excuse for refusing to take up arms, with illness, often unspecified, the second explanation most often used. Other reasons were also given. William Thornlynson denied that he was a gentleman. Another said that he was a lawyer. One man said that ‘he will do any service that he can within this realm of England, but he will not pass it.’ In all, 70 ‘gentlemen’ said they could not serve. One man was volunteered: the local community of Holderness was anxious to get rid of John Routh, ‘a right able man for your wars and one busy at home to vex your poor people as it is plainly said’. Negotiations with the Norfolk gentry were even less successful, and the commissioners sadly concluded that ‘We cannot see that the king may be served of any men here in this country as it is desired, the which is to us great heaviness and disease.’4

This meant that the proportion of knights in the armies fell dramatically. Beaufort’s army of 1443 contained just seven knights, 0.15 per cent of the total force. In contrast, 10 per cent of John of Gaunt’s force in 1370 had been knights. One reason was that there was a decline in the number of knights in the country; it seems likely that there were no more than about 200 in the 1430s. This fall needs to be qualified by the fact that esquires were coming to take the place in society that had been held by knights. In war they served as men-at-arms, just as knights did. Even so, the numbers available for recruitment were limited: ‘In Warwickshire in 1436 there were eighteen knights, fifty-nine esquires and something in the region of fifty-five gentlemen.’5 The latter regarded themselves as entitled to bear coats of arms, but their expectation was that they would serve in local politics and administration, looking to law not war. The war, particularly in its final phases, did not see society become increasingly militarized; rather, the reverse was the case.

ARCHERS AND OTHERS

As noble and knightly involvement in the war declined, the proportion of archers in English armies rose. Whereas it had been normal in the late fourteenth century for there to be equal numbers of archers and men-at-arms, as when the Earl of Warwick agreed to serve in 1373 with 200 men-at-arms and 200 archers, by Henry V’s reign a ratio of one man-at-arms to three archers was usual. In 1425 the Earl of Suffolk was contracted to have a force of 100 men-at-arms and 300 mounted archers for the siege of Mont-Saint-Michel. The proportion in expeditionary forces rose higher still, from one to five in 1428 to one to nine by 1449.

In contrast to the knights and men-at-arms, there was no great difficulty in recruiting archers. Pay, at 6d. a day, for a mounted archer was higher than what a skilled craftsman might expect to earn, and there was always the hope of gaining plunder. The social origins of the archers are not easy to discern, but some were men of substance, of at least yeoman status. There were veterans with extensive experience among them. Hegyn Tomson served at Harfleur for almost 30 years, on and off, and Richard Bullock served in the garrison of Saint-Lô for at least 19 years, and overall for 22.

The conventional view is that the English archers were superb soldiers, ‘some of the finest, most highly trained and militarily efficient troops that any nation ever put into the field of battle’.6 Such hyperbole is difficult to justify. The victory of Agincourt certainly owed much to the archers; the case is harder to argue for Verneuil. Archers were valuable in some minor engagements, such as the Battle of the Herrings, but they did not serve the English well at Patay. The performance of English armies by the 1440s suggests that the low proportion of men-at-arms was a disadvantage. In the final stages of the war the archers did not provide the English with the battle-winning capability they had displayed earlier.

There were some specialist troops needed. Gunners were increasingly important. In readiness for the siege of Harfleur, Henry V recruited 29 master gunners and 59 others, mostly from the Low Counties. A typical ordnance company was that established later at Rouen, consisting of a master gunner, a forger (or foundryman), his assistant, a master carpenter and his helper (to make the gun carriages and protective shields), a master mason (to prepare ammunition) and a carter. A man-at-arms and up to 18 archers provided an escort. When Meulan was besieged in 1436, this company was reinforced by eight additional gunners. Crossbowmen were valuable in siege warfare, both in attack and defence. The crossbow was slow to load, but in these circumstances that was no great disadvantage. Few were recruited in England; Gascony and Normandy provided men with this particular expertise. A number of professions made their contribution to the war effort. Armourers and fletchers were needed, and victuallers were needed in castle garrisons. Miners, mostly from the Forest of Dean, were required for siege warfare.

DISCIPLINE

The chronicler Jean de Waurin, commenting on the ill-disciplined troops from Brabant, remarked that ‘a thousand men of war of good stuff were worth more than 10,000 of such shit’.7 To judge by the ordinances that were issued, English armies should have been well disciplined. Henry V’s ordinances show that for him, obedience to orders was vital. Sacrilegious actions were forcibly forbidden, and women in childbirth were given special protection. Foraging was regulated, and there was to be no pillage in conquered territory. There were detailed regulations for the taking of prisoners. There was to be no taunting on grounds of national origin, be it English, Irish, Welsh or French. Prostitutes were allowed no nearer than a league away from the army.8

Not surprisingly, the disciplinary ordinances were not easy to enforce. The Duke of Bedford wrote in 1423 that he understood that churches were being broken into, women raped, goods seized, men imprisoned and unjust tolls levied. There were ‘certain vagabond English who wander from place to place robbing and inciting the soldiers to desert’.9 In the following year some newly arrived from England left their retinues and offered their services to whichever captain paid the best, an act of ‘fraud and deceit’. Others promptly deserted.10

FRENCH FORCES

In France there was an acknowledgement of the need for reform which was not matched in England. French forces were markedly larger than those the English could muster; Charles VII had up to 20,000 men in pay for the Normandy campaign of 1449–50. There were, however, similarities. The numbers of knights in French armies fell startlingly at the start of the fifteenth century. Only 1.7 per cent of the men-at-arms retained by the Armagnac government in 1414 were bannerets or knights. Remarkably, Pierre de Rochefort, created Marshal of France in 1417, though a banneret, was a squire, not a knight. Social changes provide part of the explanation for this decline in knighthood, but there was surely also a reluctance to take up arms in support of an unsuccessful cause. In France, unlike England or Burgundy, there was an acknowledgement that the distinction between knights and other men-at-arms had little warrant in military terms, for from the late 1430s all were paid at the same rate. The title of banneret fell out of use; command of companies went to captains. At the start of the fifteenth century the proportion of men-at-arms to gens de trait (archers and crossbowmen) stood at two to one, or even less. In agreements made in 1414, the Count of Vendôme was to serve with 2,000 men-at-arms and 1,000 gens de trait, and Arthur de Richemont with 500 men-at-arms and 100 gens de trait. By the 1430s the ratio had shifted to one man-at-arms to two archers.

Foreign mercenaries from Scotland, Spain and Italy provided an important element in French armies, particularly in the 1420s, when they formed up to half of Charles VII’s forces. In 1424, 2,500 Scottish men-at-arms and 4,000 archers mustered at Bourges. At Verneuil the English faced Lombard cavalry as well as the Scots. The battle was a disaster for the foreigners in French service, and marked the end of their recruitment on such a large scale. Nevertheless, during the siege of Orléans, foreign soldiers received about a third of the garrison’s limited food supplies, while there were 60 Scottish men-at-arms, with 300 archers, in the relief force. By 1445 there were just two companies of Scots, one of Italians and one of Spaniards in the French armies.

By the 1430s, despite the successes inspired by the Maid, French forces were in chaos. Attempts to revive the arrière-ban had failed. Proper systems of pay and review had collapsed. Undisciplined routiers and écorcheurs, completely out of royal control, ravaged the countryside, demanding goods and money. Aiming to deal with these problems, in 1439 a royal ordinance set out plans for reform. The fundamental principle was that commanders should be responsible to the king. Captains were to be appointed by the crown. Anyone who led a company without royal approval was guilty of lèse-majesté. Companies were not to seize crops or cattle. Frontier garrisons should not leave their positions, and were not to live off the land. Garrisons that were oppressing the people should be disbanded, and defence left to local lords.11 The ordinance was understandably unpopular with the nobility; it contributed to the Duke of Bourbon’s brief rebellion in 1440. However, it marked the beginning of a crucially important process which saw the transformation of the French army.

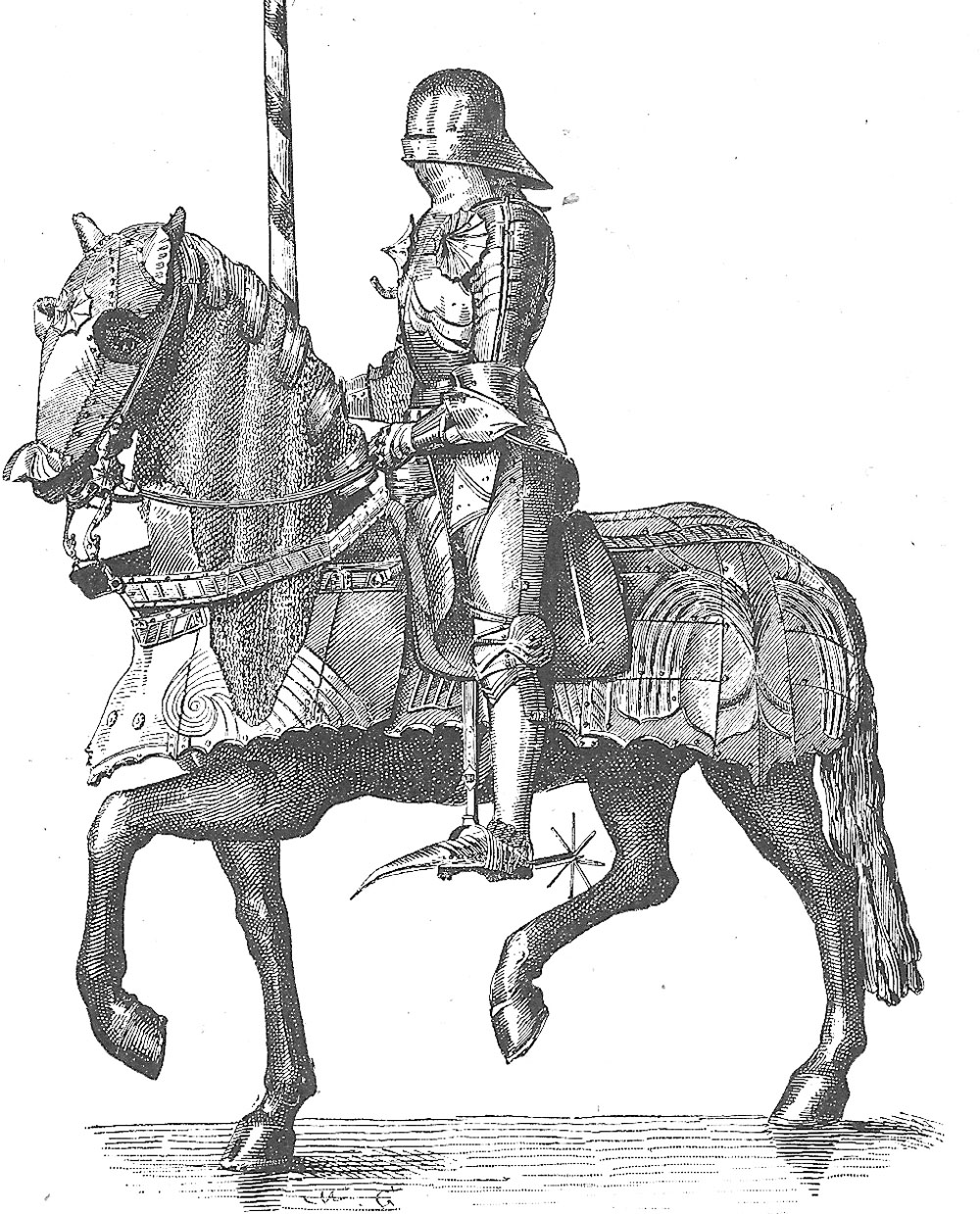

Fig. 17: A mid-fifteenth-century mounted knight

In 1445 there were fresh demands for reform, and a new military ordinance, for which Arthur de Richemont was largely responsible. It aimed to deal with the problem of the undisciplined routiers and écorcheurs who plagued France, rather than to achieve the expulsion of the English. Unfortunately the text has not survived, but its chief contents are clear. It set out the organization of the army into companies, known as compagnies d’ordonnance. The lance, composed of six men, was the basic unit for the men-at-arms. One man would be fully armed and equipped, with full armour, a second more lightly armed, with the third acting as a page. In addition there were to be two mounted archers, with their page. This provided the basis for effective, integrated forces, much as the incorporation of mounted archers into retinues had done for English armies in the fourteenth century. The victuals required by a lance were carefully worked out; each month the six men would need two sheep and half a cow. Each man was allocated a substantial two pipes of wine (252 gallons) a year. The worthless hangers-on who accompanied armies, who did no more than pillage the countryside, were to be sent home. Richemont’s biographer commented that ‘Thus the pillage of the people that had lasted so long was ended, for which my lord was joyful, for it was one of the things he most desired, and which he had always failed to achieve, but the king would not listen to him until now.’12 In 1448 there was a further important reform, when the franc-archers were established. These militia-men provided the crown with a new kind of national infantry force, intended to deal with local disorder. They were to be mustered regularly. Each man was to have a light helmet, a padded jacket or a brigandine (made of cloth heavily reinforced with plates), sword, dagger and bow. To see the reforms as amounting to the creation of a standing army is to go too far; but they did create the potential for such an army. The reforms, probably influenced by ideas drawn from Vegetius, set new standards, and it was armies created in this new spirit that achieved the French reconquest of Normandy and of English Gascony.

ARMOUR AND WEAPONRY

The chronicler Jean Chartier emphasized that the French troops who reconquered Normandy were well armoured. He described the men-at-arms ‘all armed with good cuirasses, leg armour, swords, salades [rounded helmets], of which most were garnished with silver, and with lances carried by their pages’.13 Other troops included mounted archers, equipped with brigandines, leg armour and salades. A driving force in the development of armour was the need to provide effective protection for men fighting on foot, as had become the normal practice for both English and French armies. A knight in up-to-date armour of this period looked very different from his fourteenth-century predecessor. He would no longer have a fabric surcoat or jupon; rather, he would display the bright steel plates of his armour. A breastplate in one piece replaced the ‘pair of plates’, and the armour was carefully jointed, with internal leather straps. The mail aventail, that had provided neck protection, was abandoned in favour of plate; with the great bacinet this became part of the helmet. English fashion in the early fifteenth century, as shown on memorial brasses, was for large circular besagnes to protect the shoulder joints.14 Well-made armour was little hindrance to mobility. Boucicaut was said to be able to jump into the saddle, fully armoured, without using the stirrup. He was an athlete of very considerable ability, and it was said that, after taking his helmet off, he could even perform a complete somersault wearing full armour. Nevertheless, despite the ease of movement that was possible, it still took a great deal of energy to move about in armour.

Fig. 18: A fifteenth-century French crossbowman

The hand weapons used changed little. Lances, swords, daggers, battleaxes, bill-hooks and gisarmes all featured. Crossbows were improved with the use of steel bows and winches for reloading; longbows required no development. Nor was there significant progress in the design of stone-throwing siege engines; trebuchets in particular, powered by heavy counterweights, continued in use. Traditional types of siege equipment, such as movable towers, or belfries, were also employed, while mining remained an important part of the means available to besieging forces.

GUNS

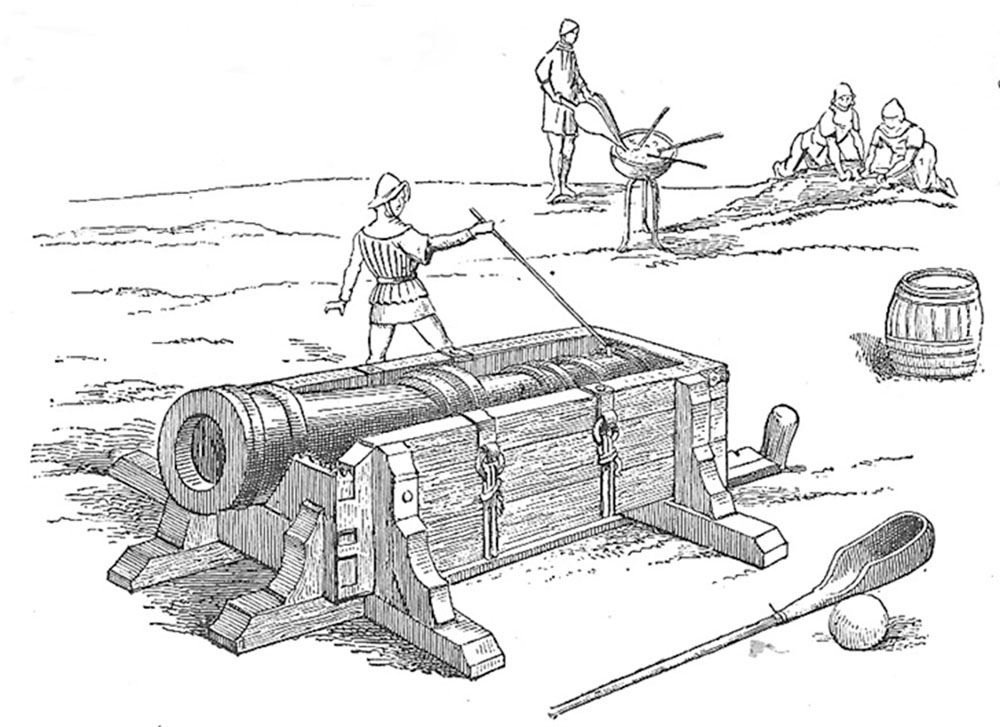

The major technological change during the Hundred Years War was the development of guns. An important shift had begun in the final quarter of the fourteenth century, when besieging forces began to employ them to good effect. The evolution speeded up in the fifteenth century. Great bombards were used extensively in siege warfare, as at Harfleur. There were various types of gun, and several methods of manufacture. The largest were normally fabricated using long staves of iron, bound together with hoops, while others were cast using bronze or iron. Most were breech-loading, with separate powder chambers: such guns would have had a faster rate of fire than muzzle-loaders. Bombards were the largest. They had a wide bore, and used stone ammunition, shot in a relatively flat trajectory. It took two years and 35 tons of iron for the donderbusmeester Pasquier den Kick to make one ordered by the Duke of Brabant in 1409. The largest bombards were capable of firing a stone of almost half a ton. Veuglaires were smaller: in 1445 a dozen Burgundian veuglaires had two chambers each, holding three pounds of powder. They could fire ammunition weighing 12 lbs. Crapaudaux were similar, but shorter and lighter. The smallest guns were coulovrines, handguns shooting lead bullets, used against troops, not stone walls. Guns were made more effective by improvements to gunpowder in the early fifteenth century, particularly by ‘corning’, forming it into dense grains. Furthermore, by about 1430 gunpowder came down in price, as it began to be manufactured on an increasingly large scale.

Fig. 19: Dulle Griet, a fifteenth-century bombard now in Ghent

There were many problems. The transport of huge siege guns was difficult. In 1409 a Burgundian bombard, weighing 7,700 lbs, required 25 men, 32 oxen and 31 horses to move it at a pace of a league a day. It took 48 horses in 1436 to pull the cart carrying the 22-inch calibre barrel of a gun called Bourgogne, while 36 horses hauled another cart with the powder chamber. In addition, an ‘engine’ to hoist the bombard into place was hauled by five horses. The convoy was too much for the bridges over the Marne, and boats had to be used instead.

Despite the difficulties, guns were available in considerable quantities. For his expedition to France in 1428 the Earl of Salisbury had seven bombards and 64 smaller guns, 16 of them hand-held weapons. In 1436 the Duke of Burgundy assembled an astonishing arsenal for his unsuccessful siege of Calais. By one count there were ten bombards, 60 veuglaires, 55 crapaudaux and 450 coulouvrines. The noise and smoke from a bombardment by such a battery was a weapon in itself. Guns were not always successful; a day’s bombardment in 1431 saw 412 stones fired into Lagny-sur-Marne, but the only casualty was a single chicken. Yet bombards were capable of breaching stone walls, as in 1441 when Charles VII brought ‘several bombards and other artillery against the town of Pontoise, and they fired incessantly against the walls, until it was broken in various places’.15 By the late 1440s, under the Bureau brothers, French artillery was formidable indeed, with place after place surrendering at the threat of bombardment.

Fig. 20: A nineteenth-century reconstruction drawing of a bombard

In a classic study, J. R. Hale argued that it was not until the second half of the fifteenth century, with the development in Italy of a new and more scientific approach, that defences were constructed in a novel style so as to deal with powerful artillery. Bastions offering flanking fire were a crucial element in complex interconnecting systems of defence. However, earlier in the fifteenth century in France a new style of defence against gunpowder artillery had been introduced, with earthen ramparts known as boulevards constructed around existing fortifications. With their palisades and timber reinforcements, boulevards were able to absorb the shock of gunfire, as well as providing platforms on which artillery could be mounted. Existing defences were reinforced with earth, but it was not until around 1450 that massive purpose-built artillery towers appeared.16

AN ORDINARY SOLDIER

The records provide a few glimpses of the men who served at this time. Gilet de Lointren, a poor man of good descent, aged about 30, became a man-at-arms through poverty and ‘went to the land of Normandy to seek adventure, as men-at-arms do’. He served first with the lord of Ivry for a couple of years. Then he moved from one garrison and one lord to another, until he was captured and held in prison for seven months, as he could not afford the ransom demanded of him. He made four écus, his share from ransoming an Englishman, Robin Maine. Captured again by the English, he was bought by a consortium of four, with his ransom set at 81 écus. He was held in prison for six months, and eventually agreed to serve the English, as he could not afford the sum demanded. Further captures, imprisonments and ransom demands followed, until finally he was condemned to death. The tale has an extraordinary happy ending, for a girl of about 15, a ‘maiden of good renown’, accompanied by her parents and friends, went to Lord Scales, the English commander at Alençon, and offered to marry Gilet. The sentence was deferred, and in 1424 Gilet finally received a pardon.17