lift head briefly when on stomach on a flat surface

lift head briefly when on stomach on a flat surfaceYou’ve brought your baby home and you’re giving parenthood everything you’ve got. Yet you can’t help wondering: Is everything you’ve got enough? After all, your schedule (and life as you seem to recall knowing it) is upended; you’re holding your baby as if he or she were made of glass; and you can’t remember the last time you’ve showered or slept more than two hours in a row.

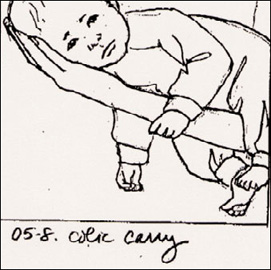

As your baby grows from a cute but largely unresponsive newborn to a full-fledged cuddly infant, your sleepless nights and hectic days will likely be filled not only with pure joy but also with exhaustion—not to mention new questions and concerns: Is my baby getting enough to eat? Why does he spit up so much? Are these crying spells considered colic? Will she (and we) ever sleep through the night? And how many times a day can I actually call the pediatrician? Not to worry. Believe it or not, by month’s end you’ll have settled into a comfortable routine with baby, one that’s still exhausting but much more manageable. You’ll also feel like a seasoned pro in the baby-care game (at least compared to what you feel like today)—feeding, burping, bathing, and handling baby with relative ease.

All babies reach milestones on their own developmental time line. If your baby seems not to have reached one or more of these milestones, rest assured, he or she probably will very soon. Your baby’s rate of development is almost certainly normal for your baby. Keep in mind, too, that skills babies perform from the tummy position can be mastered only if there’s an opportunity to practice. So make sure your baby spends supervised playtime on his or her belly. If you have concerns about your baby’s development, check with the doctor. Premature infants generally reach milestones later than others of the same birth age, often achieving them closer to their adjusted age (the age they would be if they had been born at term), and sometimes later.

All parents want to know if their babies are developing well. The problem is that when they compare their babies to the “average” baby of the same age, they find that their own child is usually ahead or behind—few are exactly average.

To help you determine whether your baby’s development fits within the wide range of normal rather than just into the limited range of “average,” we’ve developed a monthly span of achievements into which virtually all babies fall, based on the Denver Developmental Screening Tests and on the Clinical Linguistic and Auditory Milestone Scale (CLAMS). In any one month, a full 90 percent of all babies will have mastered the achievements in the first category, “What your baby should be able to do.” About 75 percent will have gained command of those in the second category, “What your baby will probably be able to do.” Roughly half will have accomplished the feats in the third category, “What your baby may possibly be able to do.” And about 25 percent will have pulled off the exploits in the last category, “What your baby may even be able to do.”

Most parents will find their babies achieving in several different categories at any one time. A few may find their offspring staying constantly in the same category. Some may find their baby’s development uneven—slow one month, making a big leap the next. All can relax in the knowledge that their babies are perfectly normal.

Only when a baby is not achieving what a child of the same age “should be able to do” on a consistent basis, need a parent be concerned and consult the doctor. Even then, no problem may exist—baby may just be marching (or rolling over, or pulling up) to a different drummer.

Use the What Your Baby May Be Doing sections of the book to check progress monthly, if you like. But don’t use them to make assessment of your baby’s abilities now or in the future. They are far from predictive. If checking your baby against such lists becomes anxiety-provoking rather than reassuring, by all means ignore them. Your baby will develop just as well if you never look at them—and you may be a lot happier.

By one month, your baby … should be able to:

lift head briefly when on stomach on a flat surface

lift head briefly when on stomach on a flat surface

focus on a face

focus on a face

… will probably be able to:

respond to a bell in some way, such as startling, crying, quieting

respond to a bell in some way, such as startling, crying, quieting

… may possibly be able to:

lift head 45 degrees when on stomach

lift head 45 degrees when on stomach

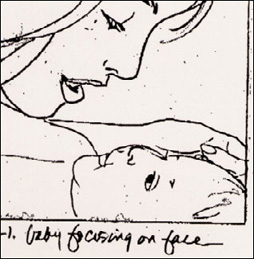

By the end of this month, a baby should be able to focus on a face.

vocalize in ways other than crying (e.g. cooing)

vocalize in ways other than crying (e.g. cooing)

smile in response to your smile

smile in response to your smile

… may even be able to:

lift head 90 degrees when on stomach

lift head 90 degrees when on stomach

hold head steady when upright

hold head steady when upright

bring both hands together

bring both hands together

smile spontaneously

smile spontaneously

Well-baby checkups will be events you’ll come to look forward to; not only as an opportunity to see how much your baby’s grown, but to ask the dozens of questions that have come up since the last visit with the practitioner but didn’t rate an immediate frantic phone call (there will be plenty of those, too). Make sure you keep a list of these questions and bring them along to appointments.

Each practitioner will have his or her own approach to well-baby checkups. The overall organization of the physical exam, as well as the number and type of assessment techniques used and procedures performed, will also vary with the individual needs of the child. But, in general, you can expect the following at a checkup when your baby is between one and four weeks old. (The first visit may take place earlier, or there may be more than one checkup in the first month, under special circumstances, such as when a newborn has had jaundice, was premature, or when there are any problems with breastfeeding.)

Questions about how you and baby and the family are doing at home, and about baby’s eating, sleeping, bowel movements, and general progress.

Questions about how you and baby and the family are doing at home, and about baby’s eating, sleeping, bowel movements, and general progress.

Measurement of baby’s weight, length, and head circumference, and plotting of progress since birth.

Measurement of baby’s weight, length, and head circumference, and plotting of progress since birth.

Vision and hearing assessments.

Vision and hearing assessments.

A report on results of neonatal screening tests (for PKU, hypothyroidism, and other inborn errors of metabolism), if not given previously. If the doctor doesn’t mention the tests, the results were very likely normal, but do ask for them for your own records. If your baby was released from the hospital before these tests were performed, or if they were done before he or she was seventy-two hours old, they will probably be performed or repeated now.

A report on results of neonatal screening tests (for PKU, hypothyroidism, and other inborn errors of metabolism), if not given previously. If the doctor doesn’t mention the tests, the results were very likely normal, but do ask for them for your own records. If your baby was released from the hospital before these tests were performed, or if they were done before he or she was seventy-two hours old, they will probably be performed or repeated now.

A physical exam. The doctor or nurse practitioner will examine all or most of the following; some evaluations will be carried out by the experienced eye or hand, without comment:

A physical exam. The doctor or nurse practitioner will examine all or most of the following; some evaluations will be carried out by the experienced eye or hand, without comment:

heart sounds with a stethoscope, and visual check of the heartbeat through the chest wall

heart sounds with a stethoscope, and visual check of the heartbeat through the chest wall

abdomen, by palpation (feeling outside), for any abnormal masses

abdomen, by palpation (feeling outside), for any abnormal masses

hips, checking for dislocation by rotating the legs

hips, checking for dislocation by rotating the legs

hands and arms, feet and legs, for normal development and motion

hands and arms, feet and legs, for normal development and motion

back and spine, for any abnormalities

back and spine, for any abnormalities

eyes, with an ophthalmoscope and/or a penlight, for normal reflexes and focusing, and for tear duct functioning

eyes, with an ophthalmoscope and/or a penlight, for normal reflexes and focusing, and for tear duct functioning

ears, with an otoscope, for color, fluid, movement

ears, with an otoscope, for color, fluid, movement

nose, with otoscope, for color and condition of mucous membranes

nose, with otoscope, for color and condition of mucous membranes

mouth and throat, using a wooden tongue depressor, for color, sores, bumps

mouth and throat, using a wooden tongue depressor, for color, sores, bumps

neck, for normal motion, thyroid and lymph gland size (lymph glands are more easily felt in infants, and this is normal)

neck, for normal motion, thyroid and lymph gland size (lymph glands are more easily felt in infants, and this is normal)

underarms, for swollen lymph glands

underarms, for swollen lymph glands

the fontanels (the soft spots on the head), by feeling with the hands

the fontanels (the soft spots on the head), by feeling with the hands

respiration and respiratory function, by observation, and sometimes with stethoscope and/or light tapping of chest and back

respiration and respiratory function, by observation, and sometimes with stethoscope and/or light tapping of chest and back

the genitalia, for any abnormalities, such as hernias or undescended testicles; the anus for cracks or fissures; the femoral pulse in the groin, for a strong, steady beat

the genitalia, for any abnormalities, such as hernias or undescended testicles; the anus for cracks or fissures; the femoral pulse in the groin, for a strong, steady beat

healing of the umbilical cord and circumcision (if applicable)

healing of the umbilical cord and circumcision (if applicable)

the skin, for color, tone, rashes, and lesions, such as birthmarks

the skin, for color, tone, rashes, and lesions, such as birthmarks

reflexes specific to baby’s age

reflexes specific to baby’s age

overall movement and behavior, ability to relate to others

overall movement and behavior, ability to relate to others

Guidance about what to expect in the next month in relation to feeding, sleeping, development, and infant safety.

Guidance about what to expect in the next month in relation to feeding, sleeping, development, and infant safety.

Possibly hepatitis B vaccination, if baby did not receive it at birth and won’t be getting the combined DTaPhepB-IPV vaccine (Pediarix) starting at two months.

Possibly hepatitis B vaccination, if baby did not receive it at birth and won’t be getting the combined DTaPhepB-IPV vaccine (Pediarix) starting at two months.

Before the visit is over, be sure to:

Ask for guidelines for calling when baby is sick. (What would necessitate a call in the middle of the night? How can the doctor be reached outside of regular calling times?)

Ask for guidelines for calling when baby is sick. (What would necessitate a call in the middle of the night? How can the doctor be reached outside of regular calling times?)

Express any concerns that may have arisen over the past month—about baby’s health, behavior, sleep, feeding, and so on.

Express any concerns that may have arisen over the past month—about baby’s health, behavior, sleep, feeding, and so on.

Jot down information and instructions from the doctor so you don’t forget.

Jot down information and instructions from the doctor so you don’t forget.

When you get home, record all pertinent information (baby’s weight, length, head circumference, blood type, test results, birthmarks) in a permanent health record.

Though this early in the parenting game you and your baby probably haven’t been apart for more than an hour or two (if that), there comes a time in every nursing mother’s life when she needs, or wants, more flexibility than round-the-clock breastfeeding can provide. When she can’t breastfeed her baby—because she’s working, traveling, or just out for the evening—but still wants her baby to be fed breast milk. Enter expressed milk.

It’s not so much a law of physics as it is a law of busy motherhood: You can’t always count on your baby and your breasts being at the same place at the same time. There is a way, however, to feed your baby breast milk (and keep your milk supply up) even if you and baby are miles apart: by expressing milk.

There are many situations (short- or long-term, on a regular schedule or just occasionally) when a mother might need or want to express breast milk, usually by pumping. The most common reasons why women pump are to:

Relieve engorgement when the milk comes in

Relieve engorgement when the milk comes in

Collect milk for feedings when working

Collect milk for feedings when working

Provide relief bottles when away from home

Provide relief bottles when away from home

Increase or maintain the milk supply

Increase or maintain the milk supply

Store milk in the freezer for emergencies

Store milk in the freezer for emergencies

Prevent engorgement and maintain milk supply when nursing is temporarily halted because of illness (mother’s or baby’s)

Prevent engorgement and maintain milk supply when nursing is temporarily halted because of illness (mother’s or baby’s)

Maintain milk supply if nursing needs to be stopped temporarily because mother is taking medication that is incompatible with nursing

Maintain milk supply if nursing needs to be stopped temporarily because mother is taking medication that is incompatible with nursing

Provide breast milk for a hospitalized sick or premature baby

Provide breast milk for a hospitalized sick or premature baby

Provide milk for bottle or tube feeding when a baby (premature or otherwise) is too weak to nurse or has an oral defect that hinders nursing

Provide milk for bottle or tube feeding when a baby (premature or otherwise) is too weak to nurse or has an oral defect that hinders nursing

Stimulate relactation, if a mother changes her mind about nursing or if a baby turns out to be allergic to cow’s milk after early weaning

Stimulate relactation, if a mother changes her mind about nursing or if a baby turns out to be allergic to cow’s milk after early weaning

Induce lactation in an adopting mother, or in a biological mother whose milk is slow in coming in

Induce lactation in an adopting mother, or in a biological mother whose milk is slow in coming in

At one time, the only way to express milk was by hand, a long and tedious process that often failed to produce significant quantities of milk (and, frankly, hurt—a lot). Today, spurred by the resurgence of breastfeeding, manufacturers are marketing a variety of breast pumps—ranging from simple hand-operated models that cost a few dollars to pricey hospital-grade electric ones (that are now more affordable for home use)—to make pumping easier and more convenient. Though an occasional mother will still express by hand, at least to relieve engorgement, most will invest in either an electric, battery-operated, or manual pump.

Before deciding which type of pump is best for you, you’ll need to do a little homework:

Consider your needs. Will you be pumping regularly because you’re going back to work or will be out of the house on a daily basis? Will you pump only once in a while to provide a relief bottle? Or will you be pumping full-time to provide nourishment for your sick or premature baby, who may be in the hospital for weeks or months?

Consider your needs. Will you be pumping regularly because you’re going back to work or will be out of the house on a daily basis? Will you pump only once in a while to provide a relief bottle? Or will you be pumping full-time to provide nourishment for your sick or premature baby, who may be in the hospital for weeks or months?

Weigh your options. If you’ll be pumping several times a day for an extended period of time (such as when working or to feed a preterm infant), a double electric pump will probably be your best bet. If you need to pump only for occasional outings, a single electric, battery, or manual pump will fill your needs (and those few bottles). If you’re planning on expressing only when you’re engorged or for a rare bottle feeding, you can probably get away with expressing by hand (though an inexpensive manual pump may still make sense; it can take a lot of squeezing by hand to fill even one bottle).

Weigh your options. If you’ll be pumping several times a day for an extended period of time (such as when working or to feed a preterm infant), a double electric pump will probably be your best bet. If you need to pump only for occasional outings, a single electric, battery, or manual pump will fill your needs (and those few bottles). If you’re planning on expressing only when you’re engorged or for a rare bottle feeding, you can probably get away with expressing by hand (though an inexpensive manual pump may still make sense; it can take a lot of squeezing by hand to fill even one bottle).

Investigate. Talk to friends who use pumps to see which they prefer. Not all pumps are created equal—not even among the electric ones. Some electric pumps can be uncomfortable to use, and some hand pumps painfully slow (and sometimes just plain painful) for expressing large quantities of milk. Also, discuss the options with a lactation consultant or your doctor. Research the types of pumps available (call up the manufacturers, check their Web sites), and consider your wallet as well as the models’ features before choosing one.

Investigate. Talk to friends who use pumps to see which they prefer. Not all pumps are created equal—not even among the electric ones. Some electric pumps can be uncomfortable to use, and some hand pumps painfully slow (and sometimes just plain painful) for expressing large quantities of milk. Also, discuss the options with a lactation consultant or your doctor. Research the types of pumps available (call up the manufacturers, check their Web sites), and consider your wallet as well as the models’ features before choosing one.

All pumps use a breast cup or shield that’s placed over your breast, centered over your nipple and areola. Whether you’re using an electric or manual pump, suction is created when the pumping action is begun, mimicking baby’s suckling. Depending on the pump you use (and how fast your let-down is), it can take anywhere from ten to forty-five minutes to pump both breasts. Pumping shouldn’t hurt; if it does, make sure you’re pumping correctly. If you are, and it still hurts, the fault might lie with the pump; consider making a switch.

It’s normal for human milk to be bluish or yellowish in color. Expressed milk will separate into milk and cream. This, too, is normal. Just shake gently to mix before feeding.

Electric pump. Powerful, fast, and easy to use (usually), a fully automatic electric pump closely imitates the rhythmic suckling action of a nursing baby. Many electric pumps allow for double pumping—a great feature if you’re pumping often. Not only does pumping both breasts simultaneously cut pumping time in half, it stimulates an increase in prolactin, which means you’ll actually produce more milk faster. Hospital-grade electric pumps are usually expensive, costing anywhere from a few hundred to a little more than a thousand dollars, but if time is an important consideration, one may be well worth the investment. (Also, when you weigh it against the cost of formula, you may break even or possibly come out ahead.)

Many women rent hospital-grade electric pumps from hospitals, pharmacies, or La Leche groups; some buy or rent jointly with other women, or buy them, use them, and then sell them (or lend them). Electric pumps also come in portable models that are inconspicuous (the black carrying cases are designed to look like backpacks or shoulder bags) and are also less expensive, smaller than and just as efficient as the hospital-grade ones. Some also come with a car adapter and/or battery pack so you don’t have to plug them in.

Battery-operated pump. Less powerful than the electric pumps, more expensive than the manual pumps, battery-operated pumps promise portability and efficient operation, but not all models deliver. They are usually moderately priced, but the speed at which some eat batteries makes them expensive to use and of questionable practicality.

Double pumping is quick, efficient, and comfortable.

Taking convenience to another level entirely are battery-operated pumps that are “wearable.” They come with soft breast cups about the size of a doughnut that are placed inside your bra and hooked up to small collection bags that lie flat against your body. Because the system is so discreet, you can wear it at the office, pumping while you work, without anyone being the wiser. And since it’s completely hands free, it’s the multitasker’s dream come true; you can pump while typing at the computer, talking on the phone, even cooking dinner. Check with your local La Leche League for the latest scoop on these.

Manual pump. These hand-operated pumps come in several styles; some are better than others:

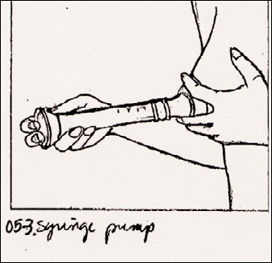

A syringe pump is composed of two cylinders, one inside the other. The inner cylinder is placed over the nipple and the outer, when pushed in and pulled out, creates suction that draws milk into it.

A syringe pump is composed of two cylinders, one inside the other. The inner cylinder is placed over the nipple and the outer, when pushed in and pulled out, creates suction that draws milk into it.

Though tough on the arm that’s doing the pumping, the syringe pump is a convenient way to express milk.

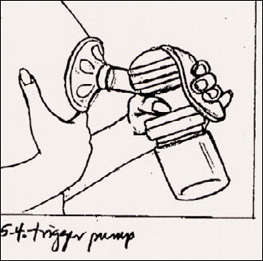

A trigger-operated pump creates suction with each squeeze of the handle. One popular type includes petal massage cushions designed to simulate the infant’s compression on the areola, which stimulates let-down.

A trigger-operated pump creates suction with each squeeze of the handle. One popular type includes petal massage cushions designed to simulate the infant’s compression on the areola, which stimulates let-down.

A bulb or “bicycle-horn” pump, which suctions milk from breasts with each squeeze of the bulb, is not recommended because it is very inefficient, uncomfortable, and extremely unsanitary (breeding bacteria that can contaminate the breast milk). It can also lead to sore nipples and damage breast tissue.

A bulb or “bicycle-horn” pump, which suctions milk from breasts with each squeeze of the bulb, is not recommended because it is very inefficient, uncomfortable, and extremely unsanitary (breeding bacteria that can contaminate the breast milk). It can also lead to sore nipples and damage breast tissue.

A trigger pump can efficiently stimulate let-down, making expressing milk an easy task.

No matter what method of expressing you choose, you may find it difficult to extract much milk the first few times. Consider those initial pumping sessions to be practice—your goal should be to figure out how to use the pump, not necessarily to score large quantities of milk. Milk probably won’t be flowing in copious amounts during early sessions anyway, for two reasons: First, you’re not producing that much milk yet (if your baby is still less than a month or two old); second, a pump (especially as wielded by a novice pumper) is much less effective in extracting milk than a baby is. But with perseverance (and practice, practice, practice), you’ll become an expert pumper in no time.

Both the syringe and trigger pumps are popular because they are fairly simple to use, moderate in price, easy to clean, portable, and can also double as feeding bottles.

Whenever you pump (and no matter what type of pump you’re using), there are basic preparation steps you’ll need to take to ensure a safe and easy pumping session:

Time it right. Choose a time of day when your breasts are ordinarily full. If you’re pumping because you’re away from your baby and missing feedings, try to pump at the same times you would normally feed, about once every three hours. If you’re home and want to stock the freezer with breast milk for emergencies or relief bottles, pump one hour after baby’s first morning feeding, since most women have more milk earlier in the day. (Late afternoon or early evening, when women typically have the least milk, thanks to exhaustion and end-of-the-day stress, is usually a particularly unproductive time to pump.) Or pump from one breast while nursing your baby from the other one; the natural let-down action your body produces for your suckling baby will help stimulate milk flow in the pumped breast as well. (But don’t try this until you’re skilled at both nursing and expressing, since this can be a tricky maneuver for a beginner).

Time it right. Choose a time of day when your breasts are ordinarily full. If you’re pumping because you’re away from your baby and missing feedings, try to pump at the same times you would normally feed, about once every three hours. If you’re home and want to stock the freezer with breast milk for emergencies or relief bottles, pump one hour after baby’s first morning feeding, since most women have more milk earlier in the day. (Late afternoon or early evening, when women typically have the least milk, thanks to exhaustion and end-of-the-day stress, is usually a particularly unproductive time to pump.) Or pump from one breast while nursing your baby from the other one; the natural let-down action your body produces for your suckling baby will help stimulate milk flow in the pumped breast as well. (But don’t try this until you’re skilled at both nursing and expressing, since this can be a tricky maneuver for a beginner).

Wash up. Wash your hands and make sure that all your pumping equipment is clean. Washing your pump immediately after each use in hot, soapy water will make the job of keeping it clean easier. If you use your pump away from home, carry along a bottle brush, detergent, and paper towels for washup.

Wash up. Wash your hands and make sure that all your pumping equipment is clean. Washing your pump immediately after each use in hot, soapy water will make the job of keeping it clean easier. If you use your pump away from home, carry along a bottle brush, detergent, and paper towels for washup.

Keep it quiet. Choose a quiet, comfortably warm environment for pumping, where you won’t be interrupted by phones or doorbells, and where you will have some privacy. At work, a private office, an unoccupied meeting room, or the women’s lounge can serve as your pumping headquarters. If you’re at home, wait until baby’s naptime, or hand baby over to someone else so you can be free to concentrate on pumping (unless you’re pumping while nursing).

Keep it quiet. Choose a quiet, comfortably warm environment for pumping, where you won’t be interrupted by phones or doorbells, and where you will have some privacy. At work, a private office, an unoccupied meeting room, or the women’s lounge can serve as your pumping headquarters. If you’re at home, wait until baby’s naptime, or hand baby over to someone else so you can be free to concentrate on pumping (unless you’re pumping while nursing).

If you’re not double pumping, the breast not being pumped will start getting into the action ahead of time and will leak accordingly. To avoid a mess, make sure the breast that’s being ignored is well packed with breast pads (especially if you’ll be going back to your desk after pumping), or take advantage of every drop of milk and collect whatever leaks in a bottle, a clean cup, or a milk cup.

Get comfy. Make yourself comfortable, with your feet up, if possible. Relax for several minutes before beginning. Use meditation or other relaxation techniques, music, TV, or whatever you find helps you unwind.

Get comfy. Make yourself comfortable, with your feet up, if possible. Relax for several minutes before beginning. Use meditation or other relaxation techniques, music, TV, or whatever you find helps you unwind.

Hydrate. Drink some water, juice, milk, decaffeinated tea or coffee, or broth just before beginning.

Hydrate. Drink some water, juice, milk, decaffeinated tea or coffee, or broth just before beginning.

Encourage let-down. Think about your baby, look at baby’s photo, and/or picture yourself nursing, to help stimulate let-down. If you’re home, giving baby a quick cuddle just before you start pumping could do the trick. If you’re using a “wearable” pump or an electric pump that leaves your hands free (by using a special “bra” devised to keep the pumps in place), you can even hold the baby—though many babies balk at being so near and yet so far from the source of their food (“Hey … why’s that machine having all the fun?”). Applying hot soaks to your nipples and breasts for five or ten minutes, taking a hot shower, doing breast massage, or leaning over and shaking your breasts are other ways of enhancing let-down.

Encourage let-down. Think about your baby, look at baby’s photo, and/or picture yourself nursing, to help stimulate let-down. If you’re home, giving baby a quick cuddle just before you start pumping could do the trick. If you’re using a “wearable” pump or an electric pump that leaves your hands free (by using a special “bra” devised to keep the pumps in place), you can even hold the baby—though many babies balk at being so near and yet so far from the source of their food (“Hey … why’s that machine having all the fun?”). Applying hot soaks to your nipples and breasts for five or ten minutes, taking a hot shower, doing breast massage, or leaning over and shaking your breasts are other ways of enhancing let-down.

Though the basic principle of expressing milk is the same whichever pump you use (stimulation and compression of the areola draws milk from the ducts out through the nipples), there are subtle differences in techniques depending on the type of pump (or, in the case of hand expression, nonpump) you’re using.

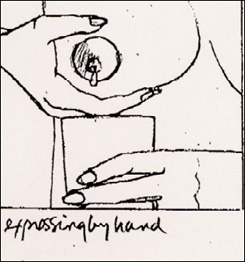

Expressing milk by hand. To begin, place your hand on one breast, with your thumb and forefingers opposite each other around the edge of the areola. Press your hand in toward your chest, gently pressing thumb and forefinger together while pulling forward slightly. (Don’t let your fingers slip onto the nipple.) Repeat rhythmically to start milk flowing, rotating your hand position to get to all milk ducts. Repeat with the other breast, massaging in between expressions, as needed. Repeat with the first breast, then do the second again.

Expressing breast milk by hand is a slow process. This method is best for expressing only small amounts, as when the breast is too engorged for baby to get a comfortable mouthful.

To massage your breast, place one hand underneath your breast, the other on top. Slide the palm of one hand or both from the chest gently toward the nipple and apply mild pressure. Rotate your hands around the breast, and repeat in order to reach all the milk ducts.

If you want to collect the milk expressed, use a clean wide-topped cup under the breast you’re working on. You can collect whatever drips from the other breast by placing a breast shell2 over it inside your bra. Collected milk should be poured into bottles or storage bags and refrigerated as soon as possible (see page 162).

Expressing milk with a manual pump. Follow the directions for the pump you are using. You might find moistening the outer edge of the flange with water or breast milk will ensure a good suction, but it’s not a necessary step. The flange should surround the nipple and areola, with all of the nipple and part of the areola in it. Use quick, short pulses at the start of the pumping session to closely imitate baby’s sucking action. Once let-down occurs, you can switch to long, steady strokes. If you want to use a hand pump on one breast while nursing your baby on the other, prop the baby at your breast on a pillow (being sure he or she can’t tumble off your lap).

Expressing milk with an electric pump. Follow the directions for the pump you are using. Double pumping is ideal because it saves time and increases milk volume. You might want to moisten the outer edge of the flange with water or breast milk to ensure a good suction. Start out on the minimum suction and increase it as the milk begins to flow, if necessary. If your nipples are sore, keep the pump at the lower setting. You might find you get more milk from one breast than the other when you double pump—that’s normal, because each breast functions independently of the other.

Many pumps come with containers that can be used as storage and feeding bottles; others allow you to use a standard feeding bottle to collect the milk. Special breast milk storage bags are convenient for freezing milk. (Disposable bottle liners are made of thinner plastic than the milk storage bags and can break more easily.) Some pumps allow you to collect the expressed milk directly into the storage bags, so you don’t need the extra step of transferring the milk from bottle to bag before storing. Be sure to wash any containers or bottles used for milk collection in hot soapy water or a dishwasher after you’re done.

Fill breast milk storage containers or bags for the freezer only three-fourths full to allow for expansion, and label with the date (always use the oldest milk first).

Keep the milk that you expressed fresh and safe for baby by keeping these storage guidelines in mind:

Refrigerate expressed milk as soon as you can; if that’s not possible, breast milk will stay fresh at room temperature (but away from radiators, sun, or other sources of heat) for as long as six hours.

Refrigerate expressed milk as soon as you can; if that’s not possible, breast milk will stay fresh at room temperature (but away from radiators, sun, or other sources of heat) for as long as six hours.

Store breast milk for up to forty-eight hours in the refrigerator, or chill for thirty minutes, then freeze.

Store breast milk for up to forty-eight hours in the refrigerator, or chill for thirty minutes, then freeze.

Breast milk will stay fresh in the freezer for anywhere from a week or two in a single-door refrigerator, to about three months in a two-door frost-free model that keeps foods frozen solid, to six months in a freezer that maintains a 0°F temperature.

Breast milk will stay fresh in the freezer for anywhere from a week or two in a single-door refrigerator, to about three months in a two-door frost-free model that keeps foods frozen solid, to six months in a freezer that maintains a 0°F temperature.

Freeze milk in small quantities, 3 to 4 ounces at a time, to minimize waste and allow for easier thawing.

Freeze milk in small quantities, 3 to 4 ounces at a time, to minimize waste and allow for easier thawing.

To thaw breast milk, shake the bottle or bag under lukewarm tap water; then use within thirty minutes. Or thaw in the refrigerator and use within twenty-four hours. Do not thaw in a microwave oven, on the top of the stove, or at room temperature; and do not refreeze.

To thaw breast milk, shake the bottle or bag under lukewarm tap water; then use within thirty minutes. Or thaw in the refrigerator and use within twenty-four hours. Do not thaw in a microwave oven, on the top of the stove, or at room temperature; and do not refreeze.

When your baby has finished feeding on a bottle, discard the remaining milk. Also discard any milk that has been stored for periods longer than those recommended above.

“I’m so afraid of handling the baby—he’s so tiny and fragile looking.”

Newborn babies may look as fragile as porcelain dolls, but they’re not. In fact, they’re really pretty sturdy. As long as their heads are well supported, they can’t be harmed by normal handling—even when it’s a little clumsy and tentative, as is often the case when the handling’s being done by a first-time parent. You’ll gradually learn what’s comfortable for your baby and for you, since handling styles vary greatly from parent to parent. Soon you’ll be toting your baby as casually as a bag of groceries—and often with a bag of groceries. For handling instructions, see pages 144–146.

“I’m so nervous when I handle my baby’s head—that soft spot seems so vulnerable. Sometimes it seems to pulsate, which really makes me nervous.”

That “soft spot”—actually there are two and they are called fontanels—is tougher than it looks. The sturdy membrane covering the fontanels is capable of protecting the newborn from the probing of even the most curious sibling fingers (though that’s definitely not something you’d want to encourage), and certainly from everyday handling.

These openings in the skull, where the bones haven’t yet grown together, aren’t there to make new parents nervous about handling baby (though that’s often the upshot) but, rather, for two very important reasons. During childbirth, they allow the fetal head to mold to fit through the birth canal, something a solidly fused skull couldn’t do. Later, they allow for the tremendous brain growth of the first year.

The larger of the two openings, the anterior fontanel, is on the top of the newborn’s head; it is diamond shaped and may be as wide as two inches. It starts to close when an infant is six months old and is usually totally closed by eighteen months.

The fontanel normally appears flat, though it may bulge a bit when baby cries, and if baby’s hair is sparse and fair, the cerebral pulse may be visible through it (which is completely normal, and nothing to worry about). An anterior fontanel that appears significantly sunken is usually a sign of dehydration, a warning that the baby needs to be given fluids promptly. (Call the baby’s doctor immediately to report this symptom.) A fontanel that bulges persistently (as opposed to a little bulging with crying) may indicate increased pressure inside the head and also requires immediate medical attention.

The posterior fontanel, a smaller triangular opening toward the back of the head less than half an inch in diameter, is much less noticeable, and may be difficult for you to locate. It generally is completely closed by the third month. Fontanels that close prematurely (they rarely do) can result in a misshapen head and require medical attention.

“At three weeks, my baby seems skinnier than when he was born. What could be wrong?”

Occasionally, an infant who had a lot of facial swelling at birth begins to look thinner as the swelling goes down. Most, however, have started to fill out by three weeks, looking less like scrawny chickens and more like rounded babies. In most cases, you can expect a breastfed baby to regain his birthweight by two weeks and then gain roughly 6 to 8 ounces a week for the next couple of months. But your eyes are not necessarily a reliable gauge of your baby’s weight gain (sometimes those who see a baby every day are less likely to notice his growth than those who see him less often). If you have some doubt about whether your baby’s making that kind of progress, call the doctor’s office and ask if you could bring him in for an impromptu weighing.

If baby’s tipping the scales just fine, then chances are he’s being fed just fine. If his weight isn’t up to speed, it’s possible that he’s not getting enough to eat (see page 164).

“When my milk came in, my breasts were overflowing. Now that the engorgement is gone, I’m not leaking anymore, and I’m worried I don’t have enough milk for my son.”

Since the human breast doesn’t come equipped with ounce calibrations, it’s virtually impossible to discern with the eye how adequate your milk supply is. Instead, you’ll have to use your baby as a guide. If he seems to be happy, healthy, and gaining weight well, you’re producing enough milk. You don’t have to spray like a fountain or leak like a faucet to nurse successfully; the only milk that counts is the milk that goes into your baby. If at any time your baby doesn’t seem to be thriving, more frequent nursing plus the other tips on the opposite page should help you produce more milk.

“My baby was nursing about every three hours and seemed to be doing very well. Now, suddenly, she seems to want to nurse every hour. Could something have happened to my milk supply?”

Unlike a well, a milk supply is unlikely to dry up if it’s used regularly. In fact, quite the opposite is true: The more your baby nurses, the more milk your breasts will produce. A much more plausible explanation for your baby’s frequent trips to the breast is a growth or appetite spurt. These occur most commonly at three weeks, six weeks, and three months, but can occur at any time during an infant’s development. Sometimes, much to parental dismay, even a baby who has been sleeping through the night begins to wake for a middle-of-the-night feeding during a growth spurt. In this case, a baby’s active appetite is merely nature’s way of ensuring that her mother’s body increases milk production to meet her growth needs.

Just relax and keep your breasts handy until the growth spurt passes. Don’t be tempted to give your baby formula (or even worse, solids) to appease her appetite, because a decrease in frequency of nursing would cut down your supply of milk, which is just the opposite of what the baby ordered. Such a pattern—started by baby wanting to nurse more, leading to mom becoming anxious about the adequacy of her milk supply and offering a supplement, followed by a decrease in milk production—is one of the major causes of breastfeeding being abandoned early on.

Sometimes a baby begins to demand more daytime feedings temporarily when she begins to sleep through the night, but this, too, shall pass with time. If, however, your baby continues to want to nurse hourly (or nearly so) for more than a week, check her weight gain (and see below). It could mean she’s not getting enough to eat.

“How can I be sure that my breastfed son is getting enough to eat?”

When it comes to bottle feeding, the proof that baby’s getting enough to eat is in the bottle—the empty bottle. When it comes to breastfeeding, determining whether baby’s well fed takes a little more digging. Luckily, there are several signs you can look for to reassure yourself that your breastfed baby is getting his fair share of food:

He’s having at least five large, seedy, mustardy bowel movements a day. Fewer than five movements a day in the early weeks could indicate inadequate food intake. (Though later on, around age six weeks to three months, the rate could slow down to one a day or even one every two to three days.)

His diaper is wet when he’s changed before each feeding. A baby who urinates more than eight to ten times a day is getting adequate fluid.

His urine is colorless. A baby who is not getting enough fluids passes urine that is yellow, possibly fishy smelling, and/or contains urate crystals (these look like powdered brick, give the wet diaper a pinkish red tinge, and are normal before the mother’s breast milk comes in but not later).

You hear a lot of gulping and swallowing as your baby nurses. If you don’t, he may not be getting much to swallow. Don’t worry, however, about relatively silent eating if baby is gaining well.

He seems happy and content after most feedings. A lot of crying and fussing or frantic finger sucking after a full nursing could mean a baby is still hungry. Not all fussing, of course, is related to hunger. After eating, it could also be related to gas, an attempt to push out a bowel movement or to settle down for a nap, or a craving for attention. Or your baby could be fussy because of colic (see pages 186–187).

You experienced breast engorgement when your milk came in. Engorgement is a good sign you can produce milk. And breasts that are fuller when you get up in the morning and after three or four hours without nursing than they are after nursing indicate they are filling with milk regularly—and also that your baby is draining them. If baby is gaining well, however, lack of noticeable engorgement shouldn’t concern you.

You notice the sensation of let-down and/or experience milk leakage. Different women experience let-down differently (see page 82), but feeling it when you start nursing indicates that milk is coming down from the storage ducts to the nipples ready to be enjoyed by your baby. Not every woman notices let-down when it occurs, but its absence (in combination with signs of baby’s failure to thrive) should raise a warning flag.

You don’t start menstruating during the first three months postpartum. The period usually doesn’t return in a woman who is exclusively breastfeeding, particularly in the first three months. Its premature return may be due to changing hormone levels, reflecting inadequate milk production.

“I thought my baby was getting enough to eat, but the doctor says the baby isn’t gaining weight quickly enough. What could be the problem?“

There are a number of possible reasons why your baby may not be thriving on breast milk. Many of them can be easily remedied, so that baby can continue nursing and start gaining weight faster:

Possible problem: You’re not feeding baby often enough.

Solution: Increase feedings to at least eight to ten times in twenty-four hours. Don’t go more than three hours during the day or four at night between feedings (four-hour daytime schedules were devised for bottle-fed babies). That means waking up a sleeping baby so that he won’t miss dinner or feeding a hungry one even if he just finished a meal an hour earlier. If your baby is “happy to starve” (some newborns are) and never demands feeding, it means taking the initiative yourself and setting a busy feeding schedule for him. Frequent nursings will not only help to fill baby’s tummy (and fill out his frame), they will also stimulate your milk production.

Possible problem: You’re not draining at least one breast at each feeding.

Solution: Nursing for at least ten minutes at the first breast should drain it sufficiently; if your baby accomplishes this task, let him nurse for as long (or as little) as he likes on the second. Remember to alternate the starting breast at each feeding.

Possible problem: You’re limiting the amount of time spent at the breast. Switching breasts after only five minutes (or before baby is ready to let go) can deprive baby of the rich, fatty hindmilk necessary for weight gain.

Solution: Watch your baby—and not the clock—to ensure that he gets not only the foremilk but also the hindmilk.

Possible problem: Your baby is a lazy or ineffective suckler. This may be because he was preterm, is ill, or has abnormal mouth development (such as a cleft palate or tied tongue).

Solution: The less effective the suckling, the less milk is produced, setting baby up for failure to thrive. Until he’s a strong suckler, he will need help stimulating your breasts to provide adequate milk. This can be done with a breast pump, which you can use to empty the breasts after each feeding (save any milk you collect for future use in bottles). Until milk production is adequate, your doctor will very likely recommend supplemental bottle feedings of formula (given after breastfeeding sessions) or the use of a supplemental system, or SNS (see illustration on facing page). The SNS has the advantage of not causing nipple confusion because it doesn’t introduce an artificial nipple.

If your baby tires easily, you may be advised to nurse for only a short time at each breast (you can pump the rest later to empty the breast), then follow with a supplement of expressed milk or formula given by bottle or the supplemental nutrition system, both of which require less effort by the baby.

Possible problem: Your baby hasn’t yet learned how to coordinate his jaw muscles for suckling.

Solution: An ineffective suckler will also need help from a breast pump to stimulate his mother’s breasts to begin producing larger quantities of milk. In addition, he will need lessons in improving his suckling technique; the doctor may recommend you get help from a lactation consultant and possibly even a speech/language pathologist. While your baby is learning, he may need supplemental feedings (see above). For further suggestions on improving suckling technique, call your local La Leche League.

Possible problem: Your nipples are sore or you have a breast infection. Not only can the pain interfere with your desire to nurse, reducing nursing frequency and milk production, it can actually inhibit milk let-down.

Solution: Take steps to heal sore nipples or cure mastitis (see pages 83 and 88). But do not use a nipple shield, as this can interfere with your baby’s ability to latch on to your nipples, compounding your problems.

Possible problem: Your nipples are flat or inverted. It’s sometimes difficult for a baby to get a firm hold on such nipples. This situation sets up the negative cycle of not enough suckling, leading to not enough milk, to even less suckling, and less milk.

Solution: Help baby get a better grip during nursing by taking the outer part of the areola between your thumb and forefinger and compressing the entire area for his sucking. Use breast shells between feedings to make your nipples easier to draw out, but avoid breast shields during nursing, which, though they can draw nipples out, can prevent baby from properly grasping your nipple and sets up a longer-term problem.

Possible problem: Some other factor is interfering with milk let-down. Let-down is a physical function that can be inhibited as well as stimulated by your state of mind. If you’re embarrassed or anxious about breastfeeding in general, or in a particular situation, not only can let-down be stifled, but the volume and calorie count of your milk can be affected.

Solution: Try to feed baby where you are most at ease—in private, if nursing around other people makes you tense. To help you relax, sit in a comfortable chair, play soft music, have something nonalcoholic to drink, try meditation or relaxation techniques. Massaging the breasts or applying warm soaks also encourages let-down, as does opening your shirt and cuddling baby skin to skin.

Supplemental Nutrition System: This apparatus can supply baby with supplementary feedings while stimulating mother’s milk production. A feeding bottle hangs around the mother’s neck; slim tubes leading from the bottle are taped down her breasts, extending slightly past the nipples. The bottle is filled with mother’s own milk, collected with a breast pump, with breast milk from a milk bank, or with the formula recommended by the baby’s doctor. As baby nurses at the breast, he takes the supplement through the tube. This system avoids the nipple confusion that arises when supplementary feedings are given in a bottle (a baby must learn to suck differently at bottle than at breast) and stimulates the mother to produce more milk even as she is supplementing artificially.

Possible problem: Your baby is getting sucking satisfaction elsewhere. If your baby is getting most of his sucking satisfaction from a pacifier or other nonnutritive source, he may have little interest in the breast.

Solution: Toss out the pacifier, and nurse baby when he seems to want to suck. And don’t give him supplementary bottles of water, which not only supply nonnutritive sucking but can dampen appetite and, in excess, alter blood sodium levels.

Possible problem: You’re not burping baby between breasts. A baby who’s swallowed air can stop eating before he’s had enough because he feels uncomfortably full.

Solution: Bringing up the air will give him room for more milk. Be sure to burp baby between breasts (or even mid-breast if nursing is taking a while) whether he seems to need it or not, more often if he fusses a lot while nursing.

Possible problem: Your baby is sleeping through the night. An uninterrupted night’s sleep is great for your looks but not necessarily for your milk supply. If baby is going seven or eight (or even ten) hours a night without nursing, your milk may be diminishing, and supplementation may eventually be needed.

Solution: To make sure this doesn’t happen, you may have to wake your little sleepyhead once in the middle of the night. He shouldn’t be going longer than four hours at night without a feeding during the first month.

Possible problem: You’ve returned to work. Returning to work—and going eight to ten hours without nursing during the day—can also decrease the milk supply.

Solution: One way to prevent this is to express milk at work at least once every four hours you’re away from baby (even if you’re not using the milk for feeding).

Possible problem: You’re doing too much too soon. Producing breast milk requires a lot of energy. If you’re expending yours in other ways and not getting adequate rest, your breast milk supply may diminish.

Solution: Try a day of almost complete bed rest, followed by three or four days of taking it easy, and see if your baby isn’t more satisfied.

Possible problem: You’re sleeping on your stomach. When you sleep on your stomach, something a lot of women are eager to do after the later months of pregnancy when they couldn’t, you also sleep on your breasts. And the pressure on your breasts could cut down on your milk production.

Solution: Turn over, at least partway, to take the pressure off those mammary glands.

Possible problem: You can use some help. Solution: Breastfeeding doesn’t come easily to every mother and every baby—and chances are some guidance from a knowledgeable source, such as a lactation consultant, can put you back on course (see page 69).

Possible problem: You’re harboring placental fragments in your uterus. Your body won’t accept the fact that you’ve actually delivered until all the products of pregnancy have been expelled, including the entire placenta. Until it’s thoroughly convinced that baby’s living on the outside now, your body may not produce adequate levels of prolactin, the hormone that stimulates milk production.

Solution: If you have any abnormal bleeding or other signs of retained placental fragments, contact your practitioner at once. A dilatation and curettage (D & C) could put you and your baby on the right track to successful breastfeeding, while avoiding the danger a retained placenta can pose to your own health.

Even with your best efforts, under the best conditions, with ample support from your doctor, a lactation consultant, your spouse, and your friends, it may turn out that you’re still unable to provide all the milk your baby needs. A small percentage of women are simply unable to breastfeed their babies without supplementation, and a very few can’t breastfeed at all. The reason may be physical, such as a prolactin deficiency, insufficient mammary glandular tissue, markedly asymmetrical breasts, or damage to the nerves to the nipple caused by breast surgery. Or it could be due to excessive stress, which can inhibit let-down. Or, occasionally, it may not be pinpointed at all. An early clue that your breasts may not be able to produce adequate milk is their failure to enlarge at all during pregnancy—though it’s not an infallible clue and is often less reliable in second and subsequent pregnancies than in first ones.

If your baby isn’t thriving, and unless the problem appears to be one that can be cleared up in just a few days, his doctor is almost certain to prescribe supplemental formula feedings. Don’t despair. What’s most important is adequately nourishing your baby, not whether you give breast or bottle. In most cases, when supplementing, you can have the benefits of the direct parent-baby contact that nursing affords by letting baby suckle at your breast for pleasure (his and yours) after he’s finished his bottle, or by using a supplemental nursing system.

Once a baby who is not doing well on the breast is put on formula, he almost invariably thrives. In the rare instance that he doesn’t, a return trip to the doctor is necessary to see what it is that is interfering with adequate weight gain.

“Why does my baby have a blister on her upper lip? Is she sucking too hard?”

For a baby with a hearty appetite, there’s no such thing as sucking too hard—although a new mother with tender nipples may disagree. And though “nursing blisters,” which develop on the center of the upper lips of many newborns, both breast and bottle fed, are caused by vigorous suckling, they have no medical significance, cause the infant no discomfort, and will disappear without treatment within a few weeks to months. Sometimes, they even seem to disappear between feedings.

“I seem to be nursing my new daughter all the time. Whatever happened to the four-hour schedules I’ve heard about?”

Apparently, your baby (like all the other nursing babies you’ll notice nipping at their mothers’ breasts almost continuously in the first few months of life) hasn’t heard about the four-hour schedule. Hunger calls and she wants to eat—a lot more often than most “schedules” would permit her to.

Let her—at least for now. Three- and four-hour schedules are based on the needs of bottle-fed newborns, who usually do very well on such regimens. But most breastfed babies need to eat more often than that. That’s because breast milk is digested more quickly than formula, making them feel hungry again sooner, and because frequent nursing helps establish a good milk supply—the foundation of a successful breastfeeding relationship.

Nurse as frequently as baby seems to want to during the early weeks. But if your baby is still demanding food every hour at three weeks of age or so, check with the doctor to see if her weight gain is normal. If it isn’t, seek advice from the doctor, and see Baby Getting Enough Breast Milk, page 166. If she seems to be thriving, however, it’s time to start making demands of your own. Hourly nursing is not only too much of an emotional strain for you, it’s a physical strain as well, making you exhausted, and may actually lead to decreased milk supply. Neither is it best for your baby, since she needs longer periods of sleep and longer periods of wakefulness when she should be looking at something other than a breast. Keep in mind, too, that crying doesn’t always signal hunger; babies also cry when they’re sleepy, bored, or just in the mood for attention (for help interpreting your baby’s cries, see page 123).

Assuming your milk supply is well established, you can start slightly stretching the periods between feedings (which may also help your baby sleep better at night). When baby wakes crying an hour after feeding, don’t rush to feed her. If she still seems sleepy, try to get her back to sleep without nursing her. Before picking her up, pat or rub her or turn on a musical toy, and see if she’ll drift back off. If not, pick her up, sing softly to her, walk with her, rock her, again with the goal of getting her back to sleep. If she seems alert, change her, talk to her, distract her in some other way, even take her for a stroll outdoors. She may become so interested in you and the rest of the world that she actually forgets about your breasts—at least for a few minutes.

When you finally do nurse, don’t accept the snack-bar approach some babies try to take; encourage her to nurse at least ten minutes on each side. If she falls off to sleep, try to waken her to continue the meal. If you can manage to stretch the periods between nursings a little more each day, eventually you and baby will be on a more reasonable schedule: two to three hours, and eventually four or so. But it should be a schedule based on her hunger, not the clock.

Today, most expectant parents of twins see double on the ultrasound screen early in pregnancy, making mad postpartum dashes to the store for a second set of everything rare. But even with seven or eight months’ notice, it may be impossible to prepare completely for the day when babies make four (or, if siblings are already on the scene, more). Knowing how to plan and what to expect can provide a greater sense of control over what may seem (at least initially) a fundamentally uncontrollable situation.

Be doubly prepared. Since double blessings often come early (full term for twins may be 37 weeks, rather than 40), it’s a good idea to start organizing for the babies’arrival well in advance. Try to have every childcare item in the house and ready for use before you go to the hospital. But while it makes sense to devote a lot of time to preparations, it doesn’t make sense to exhaust yourself (particularly if your practitioner has given you specific orders to take it easy). Get plenty of rest before the babies arrive—you can expect it to be a rare luxury once they do.

Double up. Do as much as possible for your babies in tandem. That means waking them at the same time so they can be fed together, putting them in the bath (once they’re able to sit) together, walking them in the stroller together. Double burp them together across your lap, or with one on your lap and the other your shoulder. When you can’t double up, alternate. At an early age, daily baths aren’t necessary, so bathe one one night, the other the next. Or bathe them every second or third night and sponge in between. Putting them foot to foot in the same crib during the early weeks may help them sleep better—but ask your doctor first. Some experts warn that tandem sleeping can increase the SIDS risk once the twins are able to roll over.

Split up. The work, that is. When both parents are around, divide the household chores (cooking, cleaning, laundry, shopping) and the babies (you take over one baby, your spouse the other). Be sure that you alternate babies so that both children get to know both parents well, and vice versa.

Try the double-breasted approach. Nursing twins can be physically challenging but eliminates fussing with dozens of bottles and endless ounces of formula. Nursing simultaneously will save time and avoid a daily breastfeeding marathon. You can hold the babies, propped on pillows, in the football position with their feet behind you (see page 72), or, with one at each breast, their bodies crossed in front of you. Alternate the breast each baby gets at every feeding to avoid creating favorites (and to avoid mismatched breasts, should one baby turn out to be a more proficient sucker than the other, or one baby getting less to eat if one breast turns out to be a less productive provider). If you find it too difficult to breastfeed your twins exclusively, you can nurse one while you bottle feed the other—again alternating from feeding to feeding. To keep up both your energy and your milk supply, be sure to get super nutrition (including 400 to 500 extra calories per baby) and adequate rest.

Plan to have some extra hands on hand, if you’re bottle feeding. Bottle feeding twins requires either an extra set of hands or great ingenuity. If you find yourself with two babies and just two hands at feeding time, you can sit on a sofa between the babies with their feet toward the back and hold a bottle for each. Or hold them both in your arms with the bottles in bottle proppers raised to a comfortable height by pillows. You can also occasionally prop the bottle for one in a baby seat (but never lying down), while you feed the other the traditional way. Feeding them one after the other is another possibility, but that will significantly cut into the already tiny amount of time you’ll have for other activities. This procedure will also put the babies on somewhat different napping schedules if they sleep after eating, which can be good if you’d like some time alone with each, or bad if you depend on that tandem sleeping time to rest or get things done around the house.

Double the help. All new parents need help—you need it twice as much. Accept all the help you can get, from any willing source.

Double up on equipment. When you don’t have another pair of hands around to help, utilize such conveniences as baby carriers (you can use a large sling for two babies, use two slings, or tote one baby in a carrier and one in your arms), baby swings (some models can’t be used until a baby is six weeks old), and infant seats. A play yard is a safe playground for your twins as they get older, and because they’ll have each other for company, they will be willing to be relegated to it more often and for longer periods than a singleton would. Select a twin stroller to meet your needs (if you will be traversing narrow grocery aisles, for example, a back-to-front model will be more practical than a side-by-side one); you will probably find a baby carriage a waste of money. And don’t forget that you will need two car seats. Put both in the backseat of the car.

Keep twice as many records. Who took what at which feeding, who was bathed yesterday, who’s scheduled for today? Unless you keep a log (in a notebook posted on the nursery wall, or on a blackboard), you’re sure to forget. Also make note in a permanent record book of immunizations, illnesses, and so on. Though most of the time, the babies will both get everything that’s going around, occasionally only one will—and you may not remember which one.

Don’t split zzz’s. Sleep will necessarily be scarce for the first few months, but it will be scarcer if you allow your babies to waken at random during the night. Instead, when the first cries, wake the second and feed them both. Any time that both your little darlings are napping during the day, catch a few winks yourself—or at least put your feet up.

Go one-on-one. Though it won’t be easy (at least in the beginning), there are ways to find that special one-on-one time with each child during the day. When you’re better rested yourself, stagger naptime—put one child down 15 minutes before the other—so you can shower some individualized attention on the one who’s awake. Or take only one child on an errand and leave the other one with a sitter or your spouse. Join a playgroup or parent-and-me class and alternate which child you bring along each week. Even everyday baby chores, such as diapering or dressing, can become special one-onone time for each child.

Double up on support. Other parents of twins will be your best source of advice and support; be sure to tap them. Find a parents-of-twins support group in your neighborhood or, if one is lacking, start one. But avoid becoming too clannish, socializing with only the parents of twins and having your babies participate in twins-only play groups. Though there’s something indisputably different about being a twin, excluding your children from relationships with singletons will discourage normal social development with peers—the majority of whom will not be twins.

Be doubly alert, once your twins are mobile. You’ll find, as your babies begin crawling and cruising, that what one of them doesn’t think of in the way of exploits, the other will. So they will need to be watched twice as carefully.

Expect things to get doubly better. The first four months with twins are the most challenging. Once you begin to work out the many logistics, you’ll find yourself falling into an easier rhythm. Keep in mind, too, that twins are often each other’s best company—many have a way of keeping each other busy that parents of demanding singletons find enviable, and which will free you up more and more in the months and years to come.

“I’ve been breastfeeding my son for three weeks, and I’m just not enjoying it. I’d like to switch to a bottle, but I feel so guilty.”

Beginning breastfeeding can be a frustrating series of trials and (plenty of) errors. As far as enjoyment goes, it can be elusive on both sides of the breast in this early adjustment period. It’s very possible that your dissatisfaction with Breastfeeding is just the result of a bumpy start (which almost always turns into a smooth ride by the middle of the second month). So it might make sense to hold off on your decision until your baby is six weeks old (or even two months), by which time he will have received many of the benefits of breastfeeding (though there are a lot of benefits to extended breastfeeding, see page 268), and breastfeeding generally will have become much easier and more satisfying for both participants. Then, if you’re still not enjoying nursing, feel free—and free of remorse—to wean. Remember, if it doesn’t feel right for you and your baby, it probably isn’t. Trust your feelings and your instincts.

“My baby loves his bottle. If it were up to him, he’d drink all day. How do I know when to give him more formula or when to stop?”

Because their intake is regulated both by their appetite and by an ingenious supply-and-demand system, breastfed babies rarely get too much—or too little—of a good thing. Bottle-fed babies, whose intake is regulated instead by their parents, can. As long as your baby is healthy, happy, and gaining adequate weight, you know he’s getting enough formula. But he can be taking in more than he needs—especially if his bottle becomes the liquid equivalent of an all-you-can eat buffet, continuously refilled by well meaning parents even after his appetite is satisfied.

Like labor contractions, intervals between feedings are timed from the beginning of one to the beginning of the next. So a baby who nurses for forty minutes starting at 10 A.M., then sleeps for an hour and twenty minutes before eating again, is on a two-hour schedule, not a one-hour-and-twenty-minute one.

Too much formula can lead to a too chubby baby (which, research shows, can lead to a too chubby child and a too chubby adult). But it can also lead to other problems. If your baby seems to be spitting up a lot (more than normal, see page 174), if he has abdominal pain (he draws his legs up onto a tense abdomen immediately after a feeding), and/or is gaining weight excessively, he might be taking too many ounces. Your baby’s pediatrician will be able to tell you what his rate of gain should be, and how much formula (approximately) he should be getting at each feeding (see page 108). If he does seem to be taking too much, try offering smaller-volume feedings, and stop when baby seems full instead of pushing him to take more; burp more often to relieve any abdominal discomfort he may have; and ask the doctor about whether you can give him an occasional small bottle of water (to quench his thirst without filling him up). Keep in mind, too, that it may just be the sucking (not the formula that comes with it) that he’s craving; some babies need to suck more than others. If that’s the case, consider using a pacifier during the next couple of months, while this need to suck is strongest (see page 194), or help him find his fingers or fist to suck on.

“I’m wondering if I should give our daughter bottles of water instead of nursing her so often.”

Sorry, but a bottle of water is no substitute—or supplement—for your breasts right now. A baby who is exclusively breastfed gets all the fluids she needs from breast milk, and that’s exactly where she should be getting them from. Not only doesn’t she need supplementary water under normal circumstances, she shouldn’t be offered any. First of all, bottles of water (particularly early on in breastfeeding) can satisfy her appetite and her need to suck, sabotaging nursing efforts. Second of all, too much water can dangerously dilute a baby’s blood, causing chemical imbalances. This second potential problem also holds true for bottle-fed babies who are fed too much water. Though it’s fine to give a little water to a bottle-fed baby in very hot weather, it’s not usually necessary. Giving an older infant (over age four months) small sips of water from a cup, however, is fine (they won’t be able to take too much from a cup, only from a bottle). Children on solids can handle more water, whether they’re breastfed or formula-fed.

“Everybody we talk to has a different opinion on vitamins for babies. We can’t decide whether or not to give them to our new son.”

The science of nutrition is still in its relative infancy—and that includes the study of vitamins (they weren’t even given that name until 1912). With lots more to learn, and with new information being uncovered each day, it’s not surprising that recommendations on giving vitamins seem to be ever-changing and ever-conflicting. And it’s not surprising that consumers—including new parents—are often left wondering how to proceed.

What’s clear is that babies who are formula-fed don’t need supplemental vitamins of any kind, because all the nutrients they need are already in the formula (just read the label and you’ll see). Plus, the double dose of vitamins can up their risk of developing food allergies, according to researchers. The picture’s less clear when it comes to babies who are exclusively breastfed. Current research indicates that healthy breastfeeding infants get most (though not all) of the vitamins and minerals they are believed to need from breast milk (if their mothers are eating a good diet and taking a pregnancy-lactation supplement daily). The vitamins that are missing from breast milk, most notably vitamin D, can be obtained from supplemental drops (see box on pages 174–175).

Some infants may need even more in the way of supplemental nutrients—for instance, babies who have health problems that compromise their nutritional status (those who are not able to absorb certain nutrients well from their foods and/or are on restricted diets) and babies of breastfeeding vegans who eat no animal products and take no supplements themselves. The latter should receive, at the very least, vitamin B½, which may be totally absent in their mother’s milk, and probably folic acid as well; but a complete vitamin-mineral supplement with iron is usually a good idea.

Healthy older children with adequate diets, on the other hand, probably do not need routine vitamins—even if one day the oatmeal ends up on the floor, most of the yogurt appears to be smeared on the high chair tray, and the evening offering of pureed chicken is tentatively tasted, then spit out. Some physicians nevertheless recommend giving vitamin drops daily, as health insurance, and probably will recommend an over-the-counter supplement that supplies no more than the recommended daily allowance of vitamins and minerals for your older baby. Don’t give your baby any additional vitamin, mineral, or herbal supplements unless recommended by the pediatrician.

Here’s a guide to the most common supplemental nutrients your baby’s pediatrician may prescribe:

Vitamin D. This vitamin, which is necessary for proper bone development and protects against diseases such as rickets, is naturally manufactured by the skin when it is exposed to sunlight. But because not all babies get enough sun to fill their vitamin D quota (about 15 minutes a week for fair-skinned babies, more for dark-skinned babies) due to protective clothing, sunscreen, and long winter months in certain instances, and because breast milk contains only a small amount of D, the AAP recommends vitamin D supplementation for infants who are breastfed—often in the form of ACD drops (which contain vitamins A, C, and D)—beginning within the first two months of life.

Since all the vitamins and minerals a baby needs (including D) are provided by commercial baby formula, bottle-fed infants who receive more than 16 ounces of formula a day do not need any additional supplementation. (Too much vitamin D can be toxic.)

Iron. Since iron deficiency during the first eighteen months of life can cause serious developmental and behavioral problems, it’s important that babies get enough iron. Your newborn, unless premature or low birth-weight, probably arrived with a considerable iron reserve, but this will be depleted somewhere between four and six months of age.

If you’re formula feeding, iron-fortified formula (the only kind recommended by the AAP) will fill baby’s needs. Breast milk contains sufficient iron during the first six months, so if you’re nursing, there’s no need for supplemental iron until the half-year mark is reached. Once solids are started, you can guarantee that your baby will continue to fill his or her requirement for this vital mineral by serving up foods that contain supplemental iron, such as enriched cereals, meats, and green vegetables. Adequate vitamin C intake will improve iron absorption, and once your baby begins taking a lot of solids, it’s a good idea to give a vitamin C food at each meal so that the benefits of any iron taken are maximized (see page 318). Supplemental iron drops are not a first choice for babies (though they may be recommended for preemies) because they are not well tolerated and can cause staining on the teeth. Also, the mineral can be toxic in large doses, so pediatricians use drops only when necessary.

Fluoride. According to the AAP, babies do not need fluoride supplementation during the first six months of life. After six months, a fluoride supplement should be given if there isn’t adequate fluoride in your water system. If you’re uncertain of the fluoride levels in your tap water, your baby’s doctor may be able to advise you. Or you can call your local water company or water authority. If your water is from a well or other private source, you can have its fluoride content checked by a lab (ask the health department how to have this done). Then check with your pediatrician to see if any additional fluoride is necessary.

With fluoride, as with most good things, too much can be bad. Excessive intake while the teeth are developing in the gums, such as might occur when a baby drinks fluoridated water (either plain or mixed with formula) and takes a supplement, can cause “fluorosis,” or mottling (white striations appearing on the teeth). Excessive intake can also occur if a baby or young child uses fluoridated toothpaste, which they tend to swallow. The lesser forms of mottling are not noticeable or aesthetically unattractive. More serious mottling, however, is not only disfiguring, but the pitting can predispose the teeth to decay, eliminating the good that fluoride is supposed to do.