CHAPTER 19

First Aid Do’s and Don’ts

Boo-boos happen. Even when you’re conscientious, even when you’re painstakingly careful and ever vigilant, even when you’ve taken all the precautions and then some. Hopefully, most of the boo-boos that happen in your baby’s life will be small (the kiss-and-make-better variety). Still, you’ll need to know how to respond in the event of a bigger mishap, and how to care for injuries (such as cuts, bruises, burns, and breaks) that need more treatment than a cuddle—and that’s what this chapter is for. It will be even more helpful if reinforced with a live first-aid course. But don’t wait until baby tumbles down the stairs or chews on a rhododendron leaf to look up what to do in an emergency. Now—before those incidents happen—become as familiar with the procedures for treating common injuries as you are with those for bathing baby or changing a diaper, and review less common ones when appropriate (snakebite, for example, if you live in a desert area or before you go on a camping trip). See that anyone else who cares for your baby does the same.

Below are the most common injuries, what you should know about them, how to treat (and not treat) them, and when to seek medical care for them. Types of injuries are listed alphabetically (abdominal injuries, bites, and broken bones, for example), with individual injuries numbered for easy cross-reference.

A gray bar has been added to the top of these pages, making them easy to flip to in an emergency.

ABDOMINAL INJURIES

1. Internal bleeding. A severe blow to your baby’s abdomen could result in internal injury. The signs of such injury would include: bruising or other discoloration of the abdomen; vomited or coughed-up blood that is dark or bright red and has the consistency of coffee grounds (this could also be a sign of baby’s having swallowed a caustic substance); blood (it may be dark or bright red) in the stool or urine; shock (cold, clammy, pale skin; weak, rapid pulse; chills; confusion; and possibly nausea, vomiting, and/or shallow breathing). Seek emergency medical assistance by calling 911. If baby appears to be in shock (#46), treat immediately. Do not give food or drink.

2. Cuts or lacerations of the abdomen. Treat as for other cuts (#49, #50). With a major laceration, intestines may protrude. Do not try to put them back into the abdomen. Instead, cover them with a clean, moistened washcloth or diaper and get emergency medical assistance immediately.

BITES

3. Animal bites. Try to avoid moving the affected part. Call the doctor immediately. Wash wound gently and thoroughly with soap and water. Do not apply antiseptic or anything else. Control bleeding (#49, #50, #51), and apply a sterile bandage. Try to restrain animal for testing, but avoid getting bitten. Dogs, cats, bats, skunks, and raccoons that bite may be rabid, especially if they attacked unprovoked. Infection (redness, tenderness, swelling) is common with cat bites and may require antibiotics.

Low-risk dog bites (bites from a dog that is known not to have rabies) do not usually require antibiotics, but it’s important to consult your baby’s doctor for any animal bite, both to decide on the need for antibiotics and for post-exposure rabies protection. Call the doctor immediately if redness, swelling, and tenderness develop at the site of the bite.

4. Human bites. If your baby is bitten by a sibling or another child, don’t worry unless the skin is broken. If it is, wash the bite area thoroughly with mild soap and cool water by running tap water over it, if you can, or by pouring water from a pitcher or a cup. Don’t rub the wound or apply any spray or ointment (antibiotic or otherwise). Simply cover the bite with a sterile dressing and call the doctor. Use pressure to stem the bleeding (#50), if necessary. Antibiotics may be prescribed to prevent infection.

5. Insect stings or bites. Treat insect stings or bites as follows:

Scrape off the honeybee’s stinger immediately, by scraping it horizontally with the edge of a blunt butter knife, a credit card, or your fingernail, or gently remove it with tweezers or your fingers. (Try not to pinch the stinger, because doing so could inject more venom.) Then treat as below.

Scrape off the honeybee’s stinger immediately, by scraping it horizontally with the edge of a blunt butter knife, a credit card, or your fingernail, or gently remove it with tweezers or your fingers. (Try not to pinch the stinger, because doing so could inject more venom.) Then treat as below.

Remove ticks promptly, using blunt tweezers or your fingertips protected by a tissue, paper towel, or rubber glove. Grasp the bug near the head as close to baby’s skin as possible and pull upward, steadily and evenly. Don’t twist, jerk, squeeze, crush, or puncture the tick. Don’t use such folk remedies as Vaseline, gasoline, or a hot match—they can make matters worse. If you suspect Lyme disease (see page 770), call the doctor.

Remove ticks promptly, using blunt tweezers or your fingertips protected by a tissue, paper towel, or rubber glove. Grasp the bug near the head as close to baby’s skin as possible and pull upward, steadily and evenly. Don’t twist, jerk, squeeze, crush, or puncture the tick. Don’t use such folk remedies as Vaseline, gasoline, or a hot match—they can make matters worse. If you suspect Lyme disease (see page 770), call the doctor.

Wash the site of a minor bee or wasp sting, or an ant, spider, or tick bite with soap and water. Then apply ice or cold compresses (see page 756) if there appears to be swelling or pain.

Wash the site of a minor bee or wasp sting, or an ant, spider, or tick bite with soap and water. Then apply ice or cold compresses (see page 756) if there appears to be swelling or pain.

Apply calamine lotion to itchy bites, such as those caused by mosquitoes.

Apply calamine lotion to itchy bites, such as those caused by mosquitoes.

If there seems to be extreme pain after a spider bite, apply ice or cold compresses and call 911 for emergency help. Try to find the spider and take it to the hospital with you (avoid being bitten yourself), or at least be able to describe it; it might be poisonous. If you know the spider was poisonous—a black widow, brown recluse spider, tarantula, or scorpion, for example—get emergency treatment immediately, even before symptoms appear.

If there seems to be extreme pain after a spider bite, apply ice or cold compresses and call 911 for emergency help. Try to find the spider and take it to the hospital with you (avoid being bitten yourself), or at least be able to describe it; it might be poisonous. If you know the spider was poisonous—a black widow, brown recluse spider, tarantula, or scorpion, for example—get emergency treatment immediately, even before symptoms appear.

Watch for signs of hypersensitivity, such as severe pain or swelling or any degree of shortness of breath, following any bee, wasp, or hornet sting. Individuals who exhibit such symptoms with a first sting usually develop hypersensitivities, or allergies, to the venom, in which case a subsequent sting could be fatal if immediate emergency treatment is not administered. Should your baby’s reaction to a sting be anything more than pain or swelling at the immediate site of the sting, report this to the doctor, who is likely to recommend allergy testing. If allergy is diagnosed, it will probably be necessary for you to carry a beesting emergency kit with you on outings during bee season.

Watch for signs of hypersensitivity, such as severe pain or swelling or any degree of shortness of breath, following any bee, wasp, or hornet sting. Individuals who exhibit such symptoms with a first sting usually develop hypersensitivities, or allergies, to the venom, in which case a subsequent sting could be fatal if immediate emergency treatment is not administered. Should your baby’s reaction to a sting be anything more than pain or swelling at the immediate site of the sting, report this to the doctor, who is likely to recommend allergy testing. If allergy is diagnosed, it will probably be necessary for you to carry a beesting emergency kit with you on outings during bee season.

It’s possible, of course, for sensitization to bee venom to occur without a previously noticed reaction, especially in a baby. So if after a sting your baby should break out in hives all over the body, experience difficulty breathing, hoarseness, coughing, wheezing, severe headache, nausea, vomiting, thickened tongue, facial swelling, weakness, dizziness, or fainting, get immediate emergency medical attention.

It’s possible, of course, for sensitization to bee venom to occur without a previously noticed reaction, especially in a baby. So if after a sting your baby should break out in hives all over the body, experience difficulty breathing, hoarseness, coughing, wheezing, severe headache, nausea, vomiting, thickened tongue, facial swelling, weakness, dizziness, or fainting, get immediate emergency medical attention.

6. Snakebite. It’s rare that a baby is bitten by a poisonous snake (the four major types in the U.S. are rattlesnakes, copperheads, coral snakes, and cottonmouths or water moccasins—and all have fangs, which usually leave identifying marks when they bite), but such a bite is very dangerous. Because of an infant’s small size, even a tiny amount of venom can be fatal. Following such a bite, it is important to keep the baby and the affected part as still as possible. If the bite is on a limb, immobilize it, with a splint if necessary, and keep it below the level of the heart. Use a cool compress, if available, to relieve pain, but do not apply ice or give any medication without medical advice. Get prompt medical help; and be ready to identify the variety of snake if possible. If you will not be able to get medical help within an hour, apply a loose constricting band (a belt, tie, or hair ribbon loose enough for you to slip a finger under) 2 inches above the bite to slow circulation. (Do not tie such a tourniquet around a finger or toe, or around the neck, head, or trunk.) Check pulse (see page 596) beneath the tourniquet frequently to be sure circulation is not cut off, and loosen it if the limb begins to swell. Make a note of the time it was tied. Sucking out the venom by mouth (and spitting it out) may be helpful if done immediately, but do not make an incision of any kind, unless you are four or five hours from help and severe symptoms occur. If baby is not breathing, give CPR (see page 593). Treat for shock (#46), if necessary.

Treat nonpoisonous snakebites as puncture wounds (#52), and notify baby’s doctor.

7. Marine animal stings. Such stings are not usually serious, but an occasional baby or child will have a severe reaction. Medical treatment should be sought immediately as a precaution. First-aid treatment varies with the type of marine animal involved, but in general, any clinging fragments of the stinger should be gingerly brushed away with a diaper or piece of clothing (to protect your own fingers). Treatment for heavy bleeding (#51), shock (#46), or stopped breathing (see page 596), if needed, should be begun immediately. (Don’t worry about light bleeding; it may help purge toxins.) The sting of a stingray, lionfish, catfish, stonefish, or sea urchin should be soaked in very warm water, if available, for 30 minutes, or until medical help arrives. The toxins from the sting of a jellyfish or Portuguese man-of-war can be counteracted by applying alcohol, diluted ammonia, or meat tenderizer. (Pack a couple of alcohol pads in your beach bag, just in case.)

BLEEDING

see #49, #50, #51

BLEEDING, INTERNAL

see #1

BROKEN BONES OR FRACTURES

8. Possible broken arms, legs, collarbones, or fingers. It’s hard to tell when a bone is broken in a baby. Signs of a break include: a snapping sound at the time of the injury; deformity (although this could also indicate a dislocation, #17); inability to move or bear weight on the part; severe pain (persistent crying could be a clue); numbness and/or tingling (neither of which a baby would be able to tell you about); swelling and discoloration. If a fractured limb is suspected, don’t move the child (if possible) without checking with the doctor first—unless necessary for safety. If you must move baby immediately, first try to immobilize the injured limb by splinting it in the position it’s in with a ruler, a magazine, a book, or other firm object, padded with a soft cloth to protect the skin. Or use a small, firm pillow as a splint. Fasten the splint securely at the break and above and below it with bandages, strips of cloth, scarves, or neckties, but not so tightly that circulation is hampered. Check regularly to be sure the splint doesn’t cut off circulation. If no potential splint is handy, try to splint the injured limb with your arm. Though fractures in small children usually mend quickly, medical treatment is necessary to ensure proper healing. Take your child to the doctor or ER even if you only suspect a break.

9. Compound fractures. If bone protrudes through the skin, don’t touch the bone. Cover the injury, if possible, with sterile gauze or with a clean cloth diaper; control bleeding, if necessary, with pressure (#50, #51); and get emergency medical assistance.

10. Possible neck or back injury. If neck or back injury is suspected, don’t move baby at all. Call for emergency medical assistance. Cover and keep child comfortable while waiting for help, and if possible, put some heavy objects (such as books) around the child’s head to help immobilize it. Don’t give food or drink. If there is severe bleeding (#50), shock (#46), or absence of breathing (see page 596), treat these immediately.

BRUISES, SKIN

see #47

BURNS AND SCALDS

Important: If a child’s clothing is on fire, use a coat, blanket, rug, bedspread, or your own body to smother the flames.

11. Limited burns from heat. If it’s an extremity (arm, leg, foot, hand, finger) that has been burned, immerse the part in cool water (if possible, and if baby is cooperative, hold it under running cool water). If baby’s face or trunk is burned, apply cool compresses (50°F to 60°F). Continue until baby doesn’t seem to be in pain anymore, usually about half an hour. Don’t apply ice, butter, or ointments to the burn, all of which could compound the skin damage, and don’t break any blisters that form. After soaking, gently pat burned area dry and cover with nonadhesive material (such as a nonstick bandage, or in an emergency, aluminum foil). Burns on the face, hands, feet, or genitals should be seen by a doctor immediately. Any burn, even a minor one, on a child under a year old warrants a call to the doctor.

12. Extensive burns from heat. Keep baby lying flat. Remove any clothing from the burn area that does not adhere to the wound. Apply cool wet compresses (you can use a washcloth) to the injured area (but not to more than 25 percent of the body at one time). Keep the baby comfortably warm, with extremities higher than heart if they are burned. Do not apply pressure, ointments, butter or other fats, powder, or boric acid soaks to the burn. If baby is conscious and doesn’t have severe mouth burns, nurse or give water or another fluid. Transport the child to the ER at once or call for emergency medical assistance.

BE PREPARED

Discuss with your baby’s doctor what the best plan of action would be in case of injury—calling the office, going to the emergency room (ER), or following some other protocol. Recommendations may vary, depending upon the seriousness of the injury, the day of the week, and the time of day.

Discuss with your baby’s doctor what the best plan of action would be in case of injury—calling the office, going to the emergency room (ER), or following some other protocol. Recommendations may vary, depending upon the seriousness of the injury, the day of the week, and the time of day.

Keep your first-aid supplies (see page 47) in a childproof, easily manageable kit or box so they can be moved as a whole to an accident site. Make sure you have a charged cordless or cell phone handy, so that it can be taken to the site of injury in or around your home.

Keep your first-aid supplies (see page 47) in a childproof, easily manageable kit or box so they can be moved as a whole to an accident site. Make sure you have a charged cordless or cell phone handy, so that it can be taken to the site of injury in or around your home.

Near each telephone in your home, post the numbers of the doctors your family uses, the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222), the nearest hospital emergency room (or the one you plan on using), your pharmacy, the Emergency Medical Service (911), as well as the number of a close friend or neighbor you can call on in an emergency. Keep a card with the same listings in your diaper bag.

Near each telephone in your home, post the numbers of the doctors your family uses, the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222), the nearest hospital emergency room (or the one you plan on using), your pharmacy, the Emergency Medical Service (911), as well as the number of a close friend or neighbor you can call on in an emergency. Keep a card with the same listings in your diaper bag.

Know the quickest route to the ER or other emergency medical facility.

Know the quickest route to the ER or other emergency medical facility.

Take a course in baby CPR, and keep your skills current and ready to use with periodic refresher courses and regular home practice on a doll. Also become familiar with first-aid procedures for common injuries.

Take a course in baby CPR, and keep your skills current and ready to use with periodic refresher courses and regular home practice on a doll. Also become familiar with first-aid procedures for common injuries.

Keep some cash reserved in a safe place in case you need cab fare to get to the ER or a doctor’s office in an emergency.

Keep some cash reserved in a safe place in case you need cab fare to get to the ER or a doctor’s office in an emergency.

Learn to handle minor accidents calmly, which will help you keep your cool should a serious one ever occur. Your manner and tone of voice (or those of another caregiver) will affect how your baby responds to an injury. Panic or worry on your part could upset your baby. A baby who is upset is less likely to cooperate in an emergency and will be harder to treat.

Learn to handle minor accidents calmly, which will help you keep your cool should a serious one ever occur. Your manner and tone of voice (or those of another caregiver) will affect how your baby responds to an injury. Panic or worry on your part could upset your baby. A baby who is upset is less likely to cooperate in an emergency and will be harder to treat.

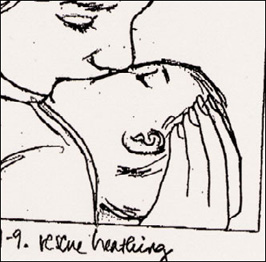

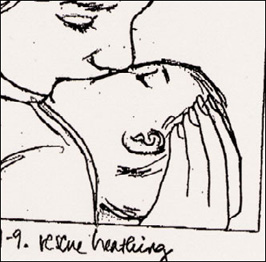

Remember that TLC (tender loving care) is often the best treatment for minor injuries. But tailor your comfort to the hurt’s degree of seriousness. A smile, a kiss, and a little reassurance (“You’re all right”) are all a little bump on the knee may need. But a painful pinched finger will probably warrant a heavy dose of kisses and some distraction. In most cases, you will need to calm a baby before giving first aid. Only in life-threatening situations (which are fortunately rare, and in which babies are not usually up to being uncooperative) will taking some time to quiet baby interfere with the outcome of treatment.

Remember that TLC (tender loving care) is often the best treatment for minor injuries. But tailor your comfort to the hurt’s degree of seriousness. A smile, a kiss, and a little reassurance (“You’re all right”) are all a little bump on the knee may need. But a painful pinched finger will probably warrant a heavy dose of kisses and some distraction. In most cases, you will need to calm a baby before giving first aid. Only in life-threatening situations (which are fortunately rare, and in which babies are not usually up to being uncooperative) will taking some time to quiet baby interfere with the outcome of treatment.

13. Chemical burns. Caustic substances (such as lye and acids) can cause serious burns. Using a clean cloth, gently brush off dry chemical matter from the skin and remove any contaminated clothing. Immediately wash the skin with large amounts of water. Call a physician, the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222), or the ER for further advice. Get immediate medical assistance if there is difficult or painful breathing, which could indicate lung injury from inhalation of caustic fumes. (If a chemical has been swallowed, see #42.)

14. Electrical burns. Immediately disconnect the power source, if possible. Or separate the victim from the source using a dry nonmetallic object such as a wooden broom, wooden ladder, rope, cushion, chair, or even a large book—but not your bare hands. Initiate CPR (page 593) if baby is not breathing. All electrical burns should be evaluated by a physician, so call your baby’s doctor or go to the ER at once.

15. Sunburn. If your baby (or anyone else in the family) gets a sunburn, treat it by applying cool tap-water compresses (see page 756) for 10 to 15 minutes, three or four times a day, until the redness subsides; the evaporating water helps to cool the skin. In between these treatments, apply pure aloe vera gel (available in pharmacies or directly from the leaves of an aloe plant if you have one), Nutraderm, Lubriderm, or a similar mild moisturizing cream. Don’t use petroleum jelly (Vaseline) on a burn, because it seals out air, which is needed for healing. Don’t give antihistamines unless they are prescribed by the doctor. For severe burns, steroid ointments or creams may be prescribed, and large blisters may be drained and dressed. A baby pain reliever, such as acetaminophen, may reduce the discomfort. If there is swelling, ibuprofen would be a better choice. As with any other burn in a baby, sunburns merit at least a call to the doctor. Extensive sunburn can cause more serious symptoms, such as headache and vomiting, and needs urgent medical evaluation.

CHEMICAL BURNS

see #13

CHOKING

(see page 589)

CONVULSIONS

16. Symptoms of a seizure or convulsion include: collapse, eyes rolling upward, stiffening of the body followed by uncontrolled jerking movements, and in the most serious cases, breathing difficulty. Brief convulsions are not uncommon with high fevers (see page 563). Deal with a seizure this way: Clear the area around baby, but don’t restrain except if necessary to prevent injury. Loosen clothing around the neck and middle, and lay baby on one side with head lower than hips. Don’t put anything in the mouth, including food or drink, breast or bottle. Call the doctor. When the convulsion has passed, sponge with cool water if fever is present, but don’t put baby into a bath or throw water in his or her face. If baby isn’t breathing, begin CPR (see page 593) immediately.

CUTS

see #49, #50

DISLOCATIONS

17. Shoulder and elbow dislocations are not as common among babies as they are among toddlers, who get them mostly because they are often tugged along by the arm by adults in a hurry (or lifted or “flown” through the air by their arms). A deformity of the arm or the inability of the child to move it, usually combined with persistent crying because of pain, are typical indications. A quick trip to the doctor’s office or the ER, where an experienced professional will reposition the dislocated part, will provide virtually instant relief. If pain seems severe, apply a cool compress and a splint before leaving (see pages 756 and 575).

DOG BITES

see #3

DROWNING (SUBMERSION INJURY)

18. Even a child who quickly revives after being taken from the water unconscious should get medical evaluation. For the child who remains unconscious, have someone else call for emergency medical assistance, if possible, while you begin CPR (see page 593). Even if no one is available to phone for help, begin CPR immediately and call later. Don’t stop CPR until the child revives or help arrives, no matter how long that takes. If there is vomiting, turn baby to one side to avoid choking. If you suspect a blow to the head or a neck injury, immobilize these parts (#10).

EAR INJURIES

19. Foreign object in the ear. Try to dislodge the object with these techniques:

For an insect, use a flashlight to try to lure it out.

For an insect, use a flashlight to try to lure it out.

For a metal object, try a magnet to draw it out (but don’t insert the magnet in the ear).

For a metal object, try a magnet to draw it out (but don’t insert the magnet in the ear).

For a plastic or wooden object that can be seen and is not deeply lodged in the ear, dab a drop of quick-drying glue (don’t use one that might bond to the skin) on a straightened paper clip and touch it to the object. Do not probe into the inner ear. Wait for the glue to dry, then pull the clip out, hopefully with the object attached. Don’t attempt this if there’s no one around to help hold the baby still.

For a plastic or wooden object that can be seen and is not deeply lodged in the ear, dab a drop of quick-drying glue (don’t use one that might bond to the skin) on a straightened paper clip and touch it to the object. Do not probe into the inner ear. Wait for the glue to dry, then pull the clip out, hopefully with the object attached. Don’t attempt this if there’s no one around to help hold the baby still.

If the above techniques fail, don’t try to dig the object out with your fingers or an instrument. Instead, take baby to the doctor’s office or the ER.

20. Damage to the ear. If a pointed object has been pushed into the ear or if your baby shows signs of ear injury (bleeding from the ear canal, sudden difficulty hearing, swollen earlobe), call the doctor.

ELECTRIC SHOCK

21. Break contact with the electrical source by turning off the power, if possible, or separate the child from the current by using a dry nonmetallic object such as a wooden broom, wooden ladder, robe, cushion, chair, or even a large book. Call for emergency medical assistance, and if baby isn’t breathing, begin CPR (see page 593).

EYE INJURY

Important: Don’t apply pressure to an injured eye, touch the eye with your fingers, or instill medications without a physician’s advice. Keep baby from rubbing the eye by holding a small cup or glass over it or by restraining baby’s hands, if necessary.

22. Foreign object in the eye. If you can see the object (lash or grain of sand, for example), wash your hands and use a moist cotton ball to gently attempt to remove it from baby’s eye, while someone else holds the baby still (attempt this only in the corner of the eye, beneath the lower lid, or on the white of the eye; stay away from the pupil to avoid scratching the cornea). Or try pulling the upper lid down over the lower for a few seconds. If those techniques don’t work, and if baby is very uncomfortable, you can also try flushing the object out by pouring a little tepid (body temperature) water from a pitcher, cup, or bottle into the eye while someone holds baby still (but be careful not to get water into baby’s nose).

Baby won’t enjoy an eye bath, but it’s crucial for washing away a corrosive substance.

If after these attempts you can still see the object in the eye or if baby still seems uncomfortable, proceed to the doctor’s office or the ER, since the object may have become embedded or scratched the eye. Don’t try to remove an embedded object yourself. Cover the eye with a sterile gauze pad taped loosely in place, or with a few clean tissues or a clean handkerchief, to alleviate some of the discomfort en route.

23. Corrosive substance in the eye. Flush the eye immediately and thoroughly with plain lukewarm water (poured from a pitcher, cup, or bottle) for 15 minutes, holding the eye open with your fingers. If just one eye is involved, keep baby’s head turned so that the unaffected eye is higher than the affected one and the chemical runoff doesn’t drip into it. Don’t use drops or ointments, and don’t allow baby to rub the eye or eyes. Call the doctor or the Poison Control Center (800-222-1222) for further instructions.

24. Injury to the eye with a pointed or sharp object. Keep baby in a semireclining position while you seek help. If the object is still in the eye, do not try to remove it. If it isn’t, cover the eye lightly with a gauze pad, clean washcloth, or facial tissue; do not apply pressure. In either case, get emergency medical assistance immediately. Though such injuries often look worse than they are, it’s wise to consult an ophthalmologist any time the eye is scratched or punctured, even slightly.

25. Injury to the eye with a blunt object. Keep baby lying faceup. Cover the injured eye with an ice pack or cold compress (see page 756). If the eye blackens, if baby seems to be having difficulty seeing or keeps rubbing the eye a lot, or if an object hit the eye at high speed, consult the doctor.

FAINTING/LOSS OF CONSCIOUSNESS

26. Check for breathing, and if it is absent begin CPR immediately (see page 593). If you detect breathing, keep baby lying flat, lightly covered for warmth if necessary. Loosen clothing around the neck. Turn baby’s head to one side and clear the mouth of any food or objects. Check briefly to see if baby could have gotten into a medicine or household cleanser (if so, call the Poison Control Center, 800-222-1222). Don’t give anything to eat or drink. Call the doctor immediately.

FINGER AND TOE INJURIES

27. Bruises. Babies, ever curious, are particularly prone to painful bruises from catching fingers in drawers and doors. For such a bruise, soak the finger in ice water. As much as an hour of soaking is recommended, with a break every 15 minutes (long enough for the finger to rewarm) to avoid frostbite. Unfortunately, few babies will sit still for this long, though you may be able to treat for a few minutes by using distraction or force. A stubbed toe will also benefit from soaking, but again it often isn’t practical with a baby who won’t cooperate. The bruised fingers and toes will swell less if kept elevated—again, not likely to happen when the victim is a baby.

TREATING A YOUNG PATIENT

Babies are rarely cooperative patients. No matter how uncomfortable the symptoms of their illness or how painful their injuries, they’re likely to consider the treatment worse. Because of their limited comprehension, it won’t help to tell them that applying pressure to a bleeding cut will make it heal faster or that the ice pack will keep a bruised finger from swelling. Your best approach when trying to treat a baby is to use distraction.

Entertainment (begun before the treatment, and hopefully, before the tears have started) in the form of a favorite music box or audiotape; a toy dog that yaps and wags its tail; a choo-choo train that can travel across the coffee table; or a parent or sibling who can dance, jump up and down, or sing silly songs can help make the difference between a successful treatment session and a disastrous one. You can also try sailing some boats in the soaking water; taking a teddy bear’s temperature; giving a doll a dose of medicine; putting an ice pack on a stuffed doggie’s boo-boo.

How forceful you will have to be about treatment will depend on the severity of the injury. A slight bruise may not warrant upsetting yourself and a baby who’s rejecting the ice pack. A severe burn, however, will certainly merit the cold soaks, even if baby screams and thrashes during the entire treatment. In most cases, try to treat at least briefly: Even a few minutes of soaking will reduce inflammation of a burn; even a few minutes of ice on a bruise will reduce swelling. Know when to call it quits. When baby’s upset outweighs the benefits of the treatment, abandon it.

If the injured finger or toe becomes very swollen very quickly, is misshapen, or can’t be straightened, suspect a break (#8). Call the doctor immediately if the bruise is from a wringer-type injury or from catching a hand or foot in the spokes of a moving wheel.

28. Bleeding under the nail. When a finger or toe is badly bruised, a blood clot may form under the nail, causing painful pressure. If blood oozes out from under the nail, press on it to encourage the flow, which will help to relieve the pressure. Soak the injury in ice water if baby will tolerate it. If the pain continues, a hole may have to be made in the nail to relieve the pressure. Your doctor can do the job or may tell you how to do it yourself.

29. Torn nail. For a small tear, secure with a piece of adhesive tape or a Band-Aid until the torn nail grows to a point where it can be trimmed. For a tear that is almost complete, trim away along the tear line and cover with a Band-Aid until the nail is long enough to protect the fingertip once again.

30. Detached nail. The nail will fall off by itself; it’s not necessary to pull it off. Soaking the finger or toe is not recommended because constant moisture of a nail bed without the protection of a nail increases the risk of fungal infections. Do make sure, however, to keep the area clean. Antibiotic ointments can be applied but are not always necessary (ask your baby’s pediatrician). Cover the nail bed with a fresh Band-Aid often, but once the nail starts growing back in, Band-Aids are not necessary. It usually takes four to six months for a nail to grow all the way back. If the redness, heat, and swelling of infection occur at any point, call the doctor.

FROSTBITE AND HYPOTHERMIA

31. Babies are extremely susceptible to frostbite, particularly on fingers and toes, ears, nose, and cheeks. In frostbite, the affected part becomes very cold and turns white or yellowish gray. Should you note such signs in your baby, immediately try to warm the frosty parts against your body—open your coat and shirt and tuck baby inside next to your skin. As soon as possible, get to a doctor or an emergency room. If that isn’t feasible immediately, get baby indoors and begin a gradual rewarming process. Don’t put a baby with frostbite right next to a radiator, stove, open fire, or heat lamp, because the damaged skin may burn; don’t try to quick-thaw in hot water, which can also add to the damage. Instead, soak affected fingers and toes directly in water that is about 102°F—just a little warmer than normal body temperature and just slightly warm to the touch. For unsoakable parts, such as nose, ears, and cheeks, use compresses (wet washcloths or towels) of the same temperature, but don’t apply pressure. Continue the soaks until color returns to the skin, usually in 30 to 60 minutes (add warm water as needed), nursing baby or giving warm (not hot) fluids by bottle or cup as you do. As frostbitten skin rewarms it becomes red and slightly swollen, and it may blister. If baby’s injury hasn’t been seen by a doctor up to this point, it is important to get medical attention now.

If, once the injured parts have been warmed, you have to go out again to take baby to the doctor (or anywhere else), be especially careful to keep the affected areas warm en route, as refreezing of thawed tissues can cause additional damage.

Much more common than frostbite (and much less serious) is frostnip. In frostnip, the affected body part is cold and pale, but rewarming (as for frostbite) takes less time and causes less pain and swelling. As with frostbite, avoid dry heat and avoid refreezing with frostnip. Though an office or ER visit isn’t necessary, a call to the doctor makes sense.

After prolonged exposure to cold, a baby’s body temperature may drop below normal levels. This is a medical emergency known as hypothermia. No time should be wasted in getting a baby who seems unusually cold to the touch to the nearest emergency room. Keep baby warm next to your body en route.

HEAD INJURIES

Important: Head injuries are usually more serious if a child falls onto a hard surface from a height equal to or greater than his or her own height, or is hit with a heavy object. Blows to the side of the head may do more damage than those to the front or back of the head.

32. Cuts and bruises to the scalp. Because of the profusion of blood vessels in the scalp, heavy bleeding is common with cuts to the head, even tiny ones, and bruises there tend to swell to egg size very quickly. Treat as you would any cut (#49, #50) or bruise (#47). Check with the doctor for all but very minor scalp wounds.

33. Possibly serious head trauma. Most babies experience several minor bumps on the head during the first year. Usually these require no more than a few make-it-better kisses from mommy or daddy, but it’s wise to observe a baby carefully for 6 hours following a severe blow to the head. Call the doctor or summon emergency medical assistance immediately if your baby shows any of these signs after a head injury:

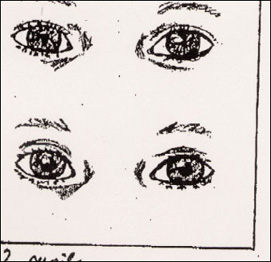

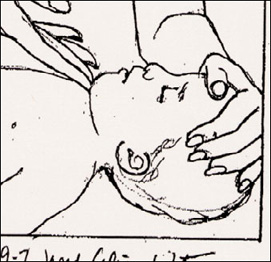

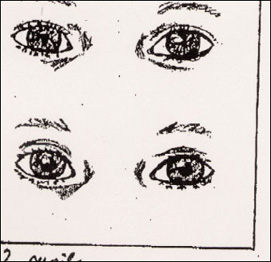

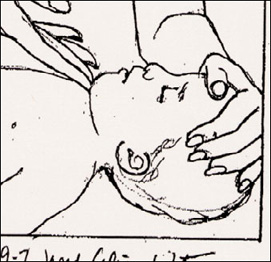

Pupils (the dark circle in the center of the eyeball) should become smaller in response to light (above) and larger once the light is removed (below).

Loss of consciousness (though a brief period of drowsiness—no more than 2 or 3 hours—is common and is usually nothing to worry about; let the degree and duration of the drowsiness be your guide)

Loss of consciousness (though a brief period of drowsiness—no more than 2 or 3 hours—is common and is usually nothing to worry about; let the degree and duration of the drowsiness be your guide)

Convulsions

Convulsions

Difficulty being roused. Check every hour or two during daytime naps, two or three times during the night for the first 6 hours following the injury to be sure baby is responsive; if you can’t rouse a sleeping baby, check for breathing: see page 594.

Difficulty being roused. Check every hour or two during daytime naps, two or three times during the night for the first 6 hours following the injury to be sure baby is responsive; if you can’t rouse a sleeping baby, check for breathing: see page 594.

More than one or two episodes of vomiting

More than one or two episodes of vomiting

A depression or indentation in the skull, or so much swelling over the wound that you can’t tell whether the skull might be depressed

A depression or indentation in the skull, or so much swelling over the wound that you can’t tell whether the skull might be depressed

Inability to move an arm or leg

Inability to move an arm or leg

Oozing of blood or watery fluid from the ears or nose

Oozing of blood or watery fluid from the ears or nose

Black-and-blue areas appearing around the eyes or behind the ears

Black-and-blue areas appearing around the eyes or behind the ears

Apparent pain for more than an hour that interferes with normal activity and/or sleep

Apparent pain for more than an hour that interferes with normal activity and/or sleep

Dizziness that persists beyond one hour after the injury (baby’s balance seems off)

Dizziness that persists beyond one hour after the injury (baby’s balance seems off)

Unequal pupil size, or pupils that don’t respond to the light of a penlight by shrinking (constricting; see illustration) or to the removal of the light by growing larger (dilating)

Unequal pupil size, or pupils that don’t respond to the light of a penlight by shrinking (constricting; see illustration) or to the removal of the light by growing larger (dilating)

Unusual paleness that persists for more than a short time

Unusual paleness that persists for more than a short time

Your baby just isn’t acting right—seems dazed, confused, doesn’t recognize you, is unusually clumsy, and so on

Your baby just isn’t acting right—seems dazed, confused, doesn’t recognize you, is unusually clumsy, and so on

While waiting for help, keep your baby lying quietly with head turned to one side. Treat for shock (#46), if necessary. Begin CPR (see page 593) if baby stops breathing.

Don’t offer any food or drink until you talk to the doctor.

HEAT INJURIES

34. Heatstroke typically comes on suddenly. Signs to watch for include hot and dry (or occasionally, moist) skin, very high fever, diarrhea, agitation or lethargy, confusion, convulsions, and loss of consciousness. If you suspect heatstroke, wrap your baby in a large towel that has been soaked in ice water (dump ice cubes in the sink while it’s filling with cold tap water, then add the towel) and summon immediate emergency medical help, or rush baby to the nearest emergency room. If the towel becomes warm, repeat with a freshly chilled one.

HYPOTHERMIA

see #31

INSECT STINGS OR BITES

see #5

LIP, SPLIT OR CUT

see #35, #36

MOUTH INJURIES

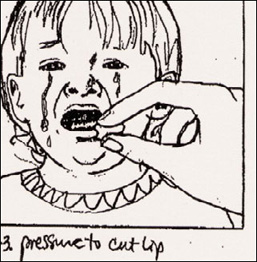

35. Split lip. Few babies escape the first year without at least one cut on the lip. Fortunately, these cuts usually look a lot worse than they are and heal a lot more quickly than you’d think. To ease pain and control bleeding, apply an ice pack. Or let an older baby suck on an ice pop. If the cut gapes open, or if bleeding doesn’t stop in 10 or 15 minutes, call the doctor. Occasionally a lip injury is caused by baby chewing on an electrical cord. If this is suspected, call the doctor.

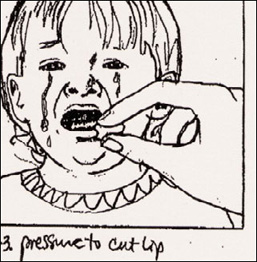

36. Cuts inside the lip or mouth (including tongue). Such injuries, too, are common in young children. An ice pack for young infants, or an ice pop to suck on will relieve pain and control bleeding inside the lip or cheek. To stop bleeding of the tongue, if it doesn’t stop spontaneously, apply pressure to cut with a piece of gauze or clean cloth. If the injury is in the back of the throat or on the soft palate (the rear of the upper mouth), if there is a puncture wound from a sharp object (such as a pencil or a stick), or if bleeding doesn’t stop within 10 to 15 minutes, call the doctor.

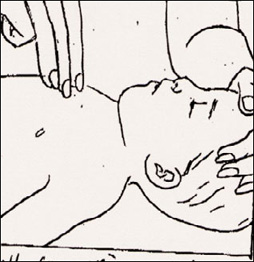

Applying pressure to a cut lip with a piece of gauze held between thumb and forefinger will stop the bleeding.

37. Knocked-out tooth. There is little chance that the dentist will try to reimplant a dislodged baby tooth (such implantations often abscess and rarely hold), so precautions to preserve the tooth aren’t necessary. But the dentist will want to see the tooth to be sure it’s whole. Fragments left in the gum could be expelled and then inhaled or choked on by the baby. So take the tooth along to the dentist or to the ER if you are unable to reach a dentist.

38. Broken tooth. Clean dirt or debris carefully from the mouth with warm water and gauze or a clean cloth. Be sure the broken parts of the tooth are not still in baby’s mouth—they could cause choking. Place cold compresses (see page 756) on the face in the area of the injured tooth to minimize swelling. Call the dentist as soon as you can for further instructions.

NOSE INJURIES

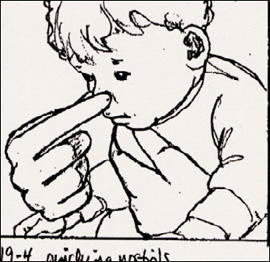

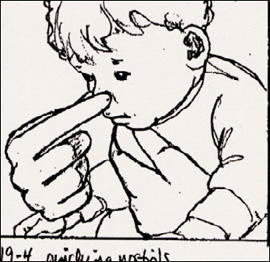

39. Nosebleeds. Keeping baby in an upright position or leaning slightly forward, pinch both nostrils gently between your thumb and index finger for 10 minutes. (Baby will automatically switch to mouth breathing.) Try to calm baby, because crying will increase the blood flow. If bleeding persists, pinch for 10 minutes more. If this doesn’t work and bleeding continues, call the doctor—keeping baby upright while you do. Frequent nosebleeds, even if easily stopped, should be reported to baby’s doctor.

Pinching the nostrils stems the flow of a bloody nose.

40. Foreign object in the nose. Difficulty breathing through the nose and/or a foul-smelling, sometimes bloody, nasal discharge may be a sign that something has been pushed up the nose. Keep baby calm and encourage mouth breathing. Remove the object with your fingers if you can reach it easily, but don’t probe or use tweezers or anything else that could injure the nose if baby moves unexpectedly or that could push the object farther into the nasal canal. If you can’t remove the object, blow through your nose and try to get baby to imitate your action. If this fails, take baby to the doctor or emergency room.

41. Blows to the nose. If there is bleeding, keep baby upright and leaning forward to reduce the swallowing of blood and the risk of choking on it (#39). Use an ice pack or cold compresses (see page 756) to reduce swelling. Check with the doctor to be sure there is no break.

POISONING

42. Swallowed poisons. Any non-food substance is a potential poison. If your baby becomes unconscious, and you know of or suspect the ingestion of a dangerous substance, begin emergency treatment immediately. Place baby face-up on a table and check for respiration (see page 594). If there is no sign of breathing, begin CPR promptly. Call for emergency medical assistance after one minute, then continue CPR until baby revives or until help arrives.

The more common symptoms of poisoning include: lethargy, agitation, or other behavior that deviates from the norm; racing, irregular pulse and/or rapid breathing; diarrhea or vomiting (baby should be turned on one side to avoid choking on vomit); excessive watering of the eyes, sweating, drooling; hot, dry skin and mouth; dilated (wide open) or constricted (pinpoint) pupils; flickering, sideways eye movements; tremors or convulsions.

If your baby has several of these symptoms (and they cannot be explained in any other way), or if you have evidence that your baby has definitely or possibly ingested a questionable substance, do not try to treat it on your own. Instead, call the Poison Control Center at 800-222-1222, or the doctor or the hospital emergency room immediately for instructions. Call even if there are no symptoms—they may not appear for hours. Take with you to the phone the container the suspected substance came in, label intact, as well as any of the remaining contents. Report the name of the substance (or of the plant if your baby ingested greenery) and how much of it you know or believe baby took, if it’s possible to determine that. Also be prepared to supply your baby’s age, size, weight, and symptoms.

Never give activated charcoal (used to absorb the poison) or anything to induce vomiting (including syrup of ipecac) without medical advice. The wrong treatment can do much more harm than good.

43. Noxious fumes or gases. Fumes from gasoline, auto exhaust, and some poisonous chemicals and dense smoke from fires can all be toxic. Promptly get a baby who has been exposed to any such hazards into fresh air (open windows or take the child outside). If baby is not breathing, begin CPR (see page 593) immediately and continue until breathing is well established or help arrives. If possible, have someone else call the Poison Control Center or an emergency medical service while you continue CPR. If no one else is around, take a moment to call for help yourself after one minute of resuscitation efforts—and then return immediately to CPR. Unless an emergency vehicle is on its way, transport baby to a medical facility promptly, but not if doing so means discontinuing CPR—or if you were also exposed and your judgment is impaired. Have someone else drive. Even if you should succeed in establishing breathing, immediate medical attention will be necessary.

POISON IVY, POISON OAK, POISON SUMAC

44. Most children who come in contact with poison ivy, poison oak, or poison sumac will have an allergic reaction (usually a red, itchy rash, with possible swelling, blistering, and oozing) that develops within 12 to 48 hours and can last from 10 days to 4 weeks. If you know your baby has had such contact, remove his or her clothing, protecting your hands from the sap (which contains the resin that triggers the reaction) with gloves, paper towels, or a clean diaper. The rash itself is not contagious and won’t spread from person to person or from one part of the body to another once the sap has been washed away (do this as quickly as possible, preferably within 10 minutes).

To prevent resin from “fixing,” wash the skin thoroughly with soap and flush with cool water for at least 10 minutes; rinse thoroughly. In a pinch, use a wipe. Also wash anything else that may have come in contact with the plants (including clothes, pets, stroller, and so on); the rash-causing resin can remain active for up to a year on such objects. Shoes can be thoroughly wiped down if they aren’t washable.

Should a reaction occur, calamine or an anti-itch lotion that contains pramoxine (such as Caladryl) will help relieve the itching, but avoid lotions that contain antihistamines (though the doctor may recommend an oral antihistamine to reduce itching and scratching, or in the case of severe poison ivy or swelling in sensitive areas, a few days of an oral steroid). Acetaminophen, cool compresses, and/or an oatmeal bath may also offer relief. Cut your baby’s nails to minimize scratching. Contact the pediatrician if the rash is severe or involves the eyes, face, or genitalia.

PUNCTURE WOUNDS

see # 52

SCRAPES

see #48

SEVERED LIMB OR DIGIT

45. Such serious injuries are rare, but knowing what to do when one occurs can mean the difference between saving and losing an arm, leg, finger, or toe. Take these steps as needed immediately:

Try to control bleeding. With several sterile gauze pads, a clean diaper, a sanitary napkin, or a clean washcloth apply heavy pressure to the wound. If bleeding continues, increase pressure. Don’t worry about doing damage by pressing too hard. Do not apply a tourniquet without medical advice.

Try to control bleeding. With several sterile gauze pads, a clean diaper, a sanitary napkin, or a clean washcloth apply heavy pressure to the wound. If bleeding continues, increase pressure. Don’t worry about doing damage by pressing too hard. Do not apply a tourniquet without medical advice.

Treat shock if present. If baby’s skin seems pale, cold, and clammy, pulse is weak and rapid, and respiration is shallow, treat for shock by loosening clothing, covering baby lightly to prevent loss of body heat, and elevating legs on a pillow (or folded garment) to force blood to the brain. If breathing seems labored, raise baby’s head and shoulders slightly.

Treat shock if present. If baby’s skin seems pale, cold, and clammy, pulse is weak and rapid, and respiration is shallow, treat for shock by loosening clothing, covering baby lightly to prevent loss of body heat, and elevating legs on a pillow (or folded garment) to force blood to the brain. If breathing seems labored, raise baby’s head and shoulders slightly.

Reestablish breathing, if necessary. Begin CPR immediately if baby isn’t breathing (see page 593).

Reestablish breathing, if necessary. Begin CPR immediately if baby isn’t breathing (see page 593).

Preserve the severed limb or digit. As soon as possible, wrap it in a wet clean cloth or sponge, and place in a plastic bag. Pack the bag with ice and tie it shut. Do not place part directly on ice, don’t use dry ice, and don’t immerse it in water or antiseptics.

Preserve the severed limb or digit. As soon as possible, wrap it in a wet clean cloth or sponge, and place in a plastic bag. Pack the bag with ice and tie it shut. Do not place part directly on ice, don’t use dry ice, and don’t immerse it in water or antiseptics.

Get help. Call or have someone else call for immediate emergency medical assistance, or rush to the ER, calling ahead so they can prepare for your arrival. Be sure to take along the ice-packed limb; surgeons may be able to reattach it. During transport, keep pressure on the wound and continue other lifesaving procedures, if necessary.

Get help. Call or have someone else call for immediate emergency medical assistance, or rush to the ER, calling ahead so they can prepare for your arrival. Be sure to take along the ice-packed limb; surgeons may be able to reattach it. During transport, keep pressure on the wound and continue other lifesaving procedures, if necessary.

SHOCK

46. Shock can develop in severe injuries or illnesses. Signs include cold, clammy, pale skin; rapid, weak pulse; chills; convulsions; and frequently, nausea or vomiting, excessive thirst, and/or shallow breathing. Call 911 immediately. Until help arrives, position baby on back. Loosen restrictive clothing, elevate legs on a pillow or folded garment to force blood to the brain, and cover baby lightly to prevent chilling or loss of body heat. If breathing seems labored, raise baby’s head and shoulders very slightly. Do not give food or water or use a hot water bottle to warm a baby in shock.

SKIN WOUNDS

Important: Exposure to tetanus is a possibility whenever the skin is broken. Should your child incur an open skin wound, check to be sure tetanus immunization is up-to-date. Also be alert for signs of possible infection (swelling, warmth, tenderness, reddening of surrounding area, oozing of pus from the wound), and call the doctor if they develop.

47. Bruises or black-and-blue marks. Encourage quiet play to rest the injured part, if possible. Apply cold compresses, an ice pack, or cloth-wrapped ice for 30 minutes. (Do not apply ice directly to the skin.) If the skin is broken, treat the bruise as you would a cut (#49, #50). Call the doctor immediately if the bruise is from a wringer-type injury or if it resulted from catching a hand or foot in the spokes of a moving wheel. Bruises that seem to appear out of nowhere or that coincide with a fever should also be seen by a doctor.

48. Scrapes or abrasions. In such injuries (most common on knees and elbows) the top layer (or layers) of skin is scraped off, leaving the area raw and tender. There is usually slight bleeding from the more deeply abraded areas. Using sterile gauze or cotton or a clean washcloth, gently sponge off the wound with soap and water to remove dirt and other foreign matter. If baby strenuously objects to this, try soaking the scrape in the bathtub. Apply pressure if the bleeding doesn’t stop on its own. Cover with a sterile nonstick bandage. Most scrapes heal quickly.

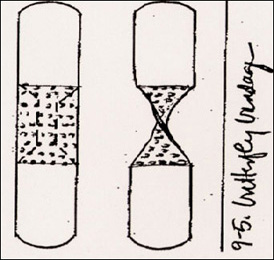

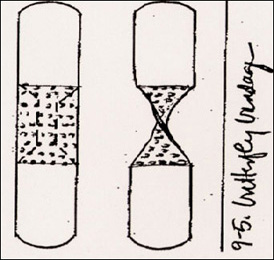

49. Small cuts. Wash the area with clean water and soap, then hold the cut under running water to flush out dirt and foreign matter. Apply a sterile nonstick Band-Aid. A butterfly bandage (see illustration) will keep a small cut closed while it heals. To prevent infection, apply an antiseptic solution or antibacterial ointment (such as bacitracin; ask the doctor for a recommendation) before putting on the bandage. Check with the doctor about any cuts on a baby’s face.

50. Large cuts. With a sterile gauze pad, a fresh diaper, a sanitary napkin, a clean washcloth, or if necessary, your bare finger, apply pressure to try to stop the bleeding, elevating the injured part above the level of the heart, if possible, at the same time. If bleeding persists after 15 minutes of pressure, add more gauze pads or cloth and increase the pressure. (Don’t worry about doing damage with too much pressure.) If necessary, keep the pressure on until help arrives or you get baby to the doctor or ER. If there are other injuries, try to tie or bandage the pressure pack in place so that your hands can be free to attend to them. Apply a sterile nonstick bandage to the wound when the bleeding stops, loose enough so that it doesn’t interfere with circulation. Do not use iodine, Burrow’s solution, or other antiseptic without medical advice. Take baby to the doctor’s office (call first) or the ER for wounds that gape, appear deep, or don’t stop bleeding within 30 minutes. Lacerations that involve the face, are longer than half an inch, are deep, or are bleeding heavily, may require stitches or surgical adhesive.

A butterfly bandage keeps a gaping cut closed so it can heal. If you don’t have one on hand, trim down a regular Band-Aid and make one complete twist to form a strong butterfly.

51. Massive bleeding. Get emergency medical attention by calling 911 or rush to the nearest ER if a limb is severed (#45) and/or blood is gushing or pumping out. In the meantime, apply pressure on the wound with gauze pads, a fresh diaper, a sanitary napkin, or a clean washcloth or towel. Increase the packing and pressure if bleeding doesn’t stop. Do not resort to a tourniquet without medical advice, as it can sometimes do more harm than good. Maintain pressure until help arrives.

52. Puncture wounds. Soak the injury in comfortably warm, soapy water for 15 minutes, if possible. Consult the baby’s doctor or go to the ER. Do not remove any object (such as a knife or stick) that protrudes from the wound, as this could lead to increased bleeding. Pad it, if necessary, to keep it from moving around. Keep baby as calm and still as possible to avoid thrashing and making the injury worse.

BANDAGING A BOO-BOO

As a parent, you can expect to apply dozens, possibly hundreds, of adhesive plastic strips and bandages over the years, on cuts and scrapes sometimes large, mostly small. These tips make bandaging easier while helping boo-boos get better faster:

Treat the injury appropriately (see individual injuries).

Treat the injury appropriately (see individual injuries).

To improve stickability, always apply Band-Aids to clean, dry skin.

To improve stickability, always apply Band-Aids to clean, dry skin.

If your baby resists bandages or tends to pick them off, or for places where it’s hard to get a Band-Aid to stay put, consider applying a liquid, gel, or spray bandage. They’re expensive, but in some cases, well worth the premium price.

If your baby resists bandages or tends to pick them off, or for places where it’s hard to get a Band-Aid to stay put, consider applying a liquid, gel, or spray bandage. They’re expensive, but in some cases, well worth the premium price.

On open wounds, use only sterile bandages or gauze pads that have not been opened prior to use. Don’t touch the face of the pad with your fingers; handle only the tape.

On open wounds, use only sterile bandages or gauze pads that have not been opened prior to use. Don’t touch the face of the pad with your fingers; handle only the tape.

Use nonstick pads and/or an antibiotic ointment to prevent the bandage from sticking to the wound. If the bandage does stick, soak it in warm water rather than trying to yank it off.

Use nonstick pads and/or an antibiotic ointment to prevent the bandage from sticking to the wound. If the bandage does stick, soak it in warm water rather than trying to yank it off.

Except for cuts that need to be held closed, bandage loosely to allow air to enter.

Except for cuts that need to be held closed, bandage loosely to allow air to enter.

Don’t wrap a bandage around a toe or finger so tightly that it cuts off circulation.

Don’t wrap a bandage around a toe or finger so tightly that it cuts off circulation.

Remove the bandage daily to check how the wound is healing (the best time is during or just after a bath, when the bandage is wet and loosened and will slip off without tugging). Rebandage the wound if it still looks raw or open. If a scab has formed on a scrape or if a cut has closed up, continued covering isn’t necessary.

Remove the bandage daily to check how the wound is healing (the best time is during or just after a bath, when the bandage is wet and loosened and will slip off without tugging). Rebandage the wound if it still looks raw or open. If a scab has formed on a scrape or if a cut has closed up, continued covering isn’t necessary.

Change bandages more often if they become wet or dirty.

Change bandages more often if they become wet or dirty.

53. Splinters or slivers. Wash the area with clean water and soap, then numb it with an ice pack (see page 758). If the sliver is completely embedded, try to work it loose with a sewing needle that has been sterilized with alcohol or the flame of a match. If one end of the sliver is clearly visible, try to remove it with tweezers (also sterilized by flame or alcohol). Don’t try to remove it with your fingernails, which might be dirty. Wash the site again after you have removed the splinter. If the splinter is not easily removed, try soaking in warm, soapy water for 15 minutes, three times a day for a couple of days, which may help it work its way out. If it doesn’t, or if the area becomes infected (indicated by redness, heat, swelling), consult the doctor. Also call the doctor if the splinter was deep and your baby’s tetanus shots are not up-to-date.

SPLINTERS OR SLIVERS

see #53

SUNBURN

see #15

SWALLOWED FOREIGN OBJECTS

54. Coins, marbles, and similar small round objects. When a baby has swallowed such an object and doesn’t seem to be in any distress, it’s best to wait for the object to travel through the digestive tract. Most children will pass a small object within two or three days. Check the stool for the object until it’s passed. The exception: If baby has swallowed a button battery consult with the doctor right away.

If, however, after ingesting such an object, your baby has difficulty swallowing, or if wheezing, drooling, gagging, vomiting, or difficulty swallowing develop later, the object may have lodged in the esophagus. Call the doctor and take your child to the emergency room immediately.

If there is coughing or there seems to be difficulty breathing, the object may have been inhaled rather than swallowed; in this case, treat it as a choking incident (see below).

55. Sharp objects. Get prompt medical attention if a swallowed object is sharp (a pin, a fish bone, a toy with sharp edges). It may have to be removed in the emergency room with a special instrument.

TEETH, INJURY TO

see #37, #38

TOE INJURIES

see #27, #28, #29, #30

TONGUE, INJURY TO

see #36

Resuscitation Techniques for Babies and Children

The instructions that follow should be used only as reinforcement. You must, for your child’s safety’s sake, take a course in baby CPR (check with baby’s doctor, a local hospital or Y, or the Red Cross for the location of a class in your community) in order to be sure you can carry out these life support procedures correctly. Periodically, reread these guidelines or those you receive at the course and run through them step by step on a doll (never on your baby or any other person, or even on a pet) so you will be able to perform them automatically should an emergency occur. Take a refresher course now and then—both to brush up on your skills and to learn the latest techniques.

WHEN BABY IS CHOKING

Coughing is nature’s way of trying to dislodge an obstruction in the airway. A baby (or anyone else) who is choking on food or some foreign object and who can breathe, cry, and cough forcefully should not be interefered with. But if after 2 or 3 minutes baby continues to cough, call the doctor. When the choking victim is struggling for breath, can’t cough effectively, is making high-pitched crowing sounds, and/or is turning blue (usually starting around the lips), begin the following rescue procedures. Begin immediately if the baby is unconscious and not breathing, and if attempts to open the airway and breathe air into the lungs (see pages 594–595, Steps A and B) are unsuccessful.

Important. An airway obstruction may also occur because of such infections as croup or epiglottitis. A choking baby who seems ill needs immediate attention at an ER. Do not waste time in a dangerous and futile attempt to try to relieve the problem.

FOR BABIES UNDER ONE YEAR

1. Get help. If someone else is present, ask them to phone for emergency medical assistance. If you’re alone and unfamiliar with rescue procedures, or if you panic and forget them, take the baby to a phone, or take a cordless or cell phone to where the child is and call for emergency medical assistance immediately. It’s also usually recommended that even if you’re familiar with rescue procedures, you take the time to call for emergency assistance before the situation worsens (it’s best to attempt rescue procedures for one minute and then call 911).

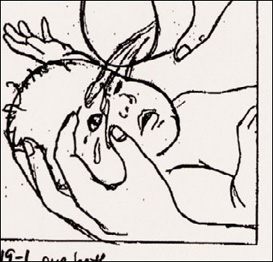

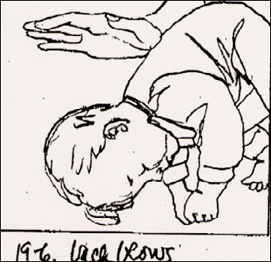

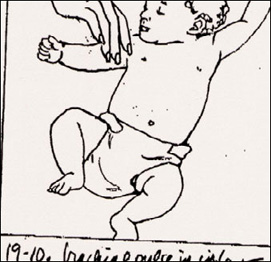

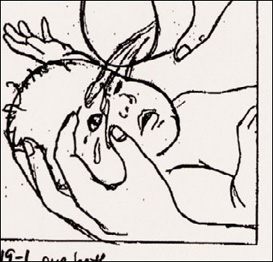

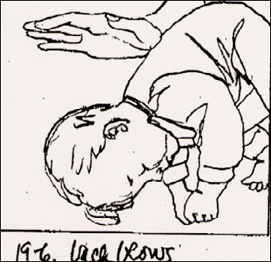

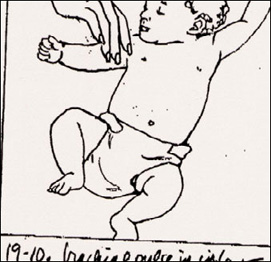

2. Position baby. Straddle baby facedown along your forearm, head lower than trunk (at about a 60-degree angle; see illustration above). Cradle baby’s chin in the curve between your thumb and forefinger. If you are seated, rest your forearm on your thigh for support. If baby is too big for you to comfortably support on your forearm, sit in a chair or on your knees on the floor and place baby face down across your lap in the same head-lower-than-body position.

3. Administer back blows. Give five consecutive forceful blows between baby’s shoulder blades with the heel of your free hand.

Back blows can often expel an inhaled object.

4. Administer chest thrusts. If there is no indication that the obstruction has been dislodged or loosened (forceful coughing, normal breathing, the object shoots out), place the flat of your free hand on the back, and, supporting the head, neck, and chest with the other hand, turn the child over, again with the head lower than the trunk. Support the head and neck with your hand, and rest your forearm on your thigh for support. (A baby who is too large to hold in this position can be placed faceup on your lap or on a firm surface.)

Imagine a horizontal line from nipple to nipple. Place the pad of your index finger just under the intersection of this line with the sternum (the flat breast-bone running midline down baby’s chest between the ribs). The area to compress is one finger’s width below this point of intersection. Position two fingers (three, if you aren’t achieving effective compression with two—but be careful to stay within the area from one finger’s width below the nipple line to above the end of the sternum) along the sternum on baby’s chest. Deliver five chest thrusts, compressing the sternum to a depth of ½ inch with each, allowing the sternum to return to its normal position in between compressions without removing your fingers. These are similar to CPR chest compressions (see page 597) but are performed at a slower rate—about 1 to 1½ seconds apart (one and, two and, three and, four and, five).

If baby is conscious, keep repeating the back blows and chest thrusts until the airway is cleared or the baby becomes unconscious. If baby is unconscious, continue below.

5. Do a foreign body check. If there is no indication that the obstruction has been dislodged or loosened (forceful coughing, normal breathing, the object shoots out), check for a visible obstruction. Open the mouth by placing your thumb in baby’s mouth, and grasp the tongue and lower jaw between your thumb and forefinger. As you lift the jaw up, depress the tongue with your thumb and move it away from the back of the throat. If you see a foreign object, attempt to remove it with a sweep of a finger. Do not sweep the mouth if you do not see an obstruction, and do not try to remove a visible obstruction with a pincer grasp, as you might force the object farther into the airway.

6. Do an airway check. If baby is still not breathing normally, open the airway with a head-tilt/chin-lift maneuver and attempt to administer two slow breaths with your mouth sealed over baby’s nose and mouth, as on page 595. If the chest rises and falls with each breath, the airway is clear.

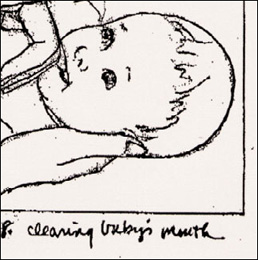

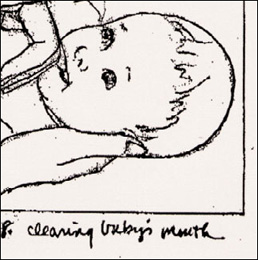

Clearing the baby’s mouth of foreign matter.

7. Repeat sequence. If the airway remains blocked, keep repeating the sequence above (items 2 through 6) until the airway is cleared and baby is conscious and breathing normally, or until emergency help has arrived. Don’t give up, since the longer the baby goes without oxygen, the more the muscles of the throat will relax, and the more likely the obstruction can be dislodged.

FOR CHILDREN OVER ONE YEAR (UNCONSCIOUS)

1. Position baby. Place child faceup on a firm, flat surface (floor or table). Stand or kneel at the child’s feet (don’t sit astride a small child) and place the heel of one hand on the abdomen in the midline between the navel and the rib cage, fingers facing toward the child’s face. Place the second hand on top of the first.

2. Administer abdominal thrusts. With the upper hand pressing against the lower, use a series of five rapid inward-and-upward abdominal thrusts to dislodge the foreign object. These thrusts should be gentler than they would be for an adult or older child. Be careful not to apply pressure to the tip of the sternum or to the ribs.

Head tilt/chin lift.

THE UNSUSPECTED INHALED OBJECT

If your baby seems to choke on something and then with or without emergency treatment, seems better, watch carefully for any signs of continued problems such as an unusual tone when crying or talking; decreased breathing sounds; wheezing; unexplained coughing; or blueness around the lips or fingernails, or of the skin generally. If any of these signs is apparent, take baby immediately to the emergency room. It’s possible an object has lodged in the lower respiratory tract.

3. Do a foreign body check. If there is no indication that the obstruction has been dislodged or loosened (forceful coughing, normal breathing, the object shoots out), check for a visible obstruction. Open the mouth by placing your thumb in baby’s mouth, and grasp the tongue and lower jaw between your thumb and forefinger. As you lift the jaw up, depress the tongue with your thumb and move it away from the back of the throat. If you see a foreign object, attempt to remove it with a sweep of a finger. Do not sweep the mouth if you do not see an obstruction, and do not try to remove a visible obstruction with a pincer grasp, as you might force the object farther into the airway.

4. Do an airway check. If the child is still not breathing spontaneously, tilt the head back slightly and administer two slow mouth-to-mouth breaths, while pinching the nostrils closed. If the chest rises and falls with each breath, the airway is clear. Check for spontaneous breathing, Step B (see page 594) and continue the procedure as necessary.

5. Repeat sequence. If the airway remains blocked, continue repeating the sequence above until the airway is cleared and the child is conscious and breathing normally, or until emergency help has arrived. Don’t give up, since the longer the child goes without oxygen, the more the muscles of the throat will relax, and the more likely the obstruction can be dislodged.

FOR CHILDREN OVER ONE YEAR (CONSCIOUS)

1. Position yourself. Stand behind the child (to reach a young child, you’ll need either to bend yourself or to elevate the child by placing him or her on a chair or table) and wrap your arms around his or her waist.

2. Position your hands. Make a fist. The thumb side of your fist should rest against the child’s abdomen in the midline, slightly above the naval and well below the tip of the breastbone.

3. Administer abdominal thrusts. Grasp the positioned fist with your other hand and press it into the child’s abdomen with five quick upward thrusts (the pressure should be less than you would use on an adult). Repeat until you see the object ejected; or the child begins breathing normally; or the child loses consciousness, in which case go to facing page.

Important: Even if your child recovers quickly from a choking episode, medical attention will be required. Call the doctor or the emergency room.

CARDIOPULMONARY RESUSCITATION (CPR): RESCUE BREATHING AND CHEST COMPRESSION

Begin the protocol below only on a baby who has stopped breathing, or on one who is struggling to breathe and turning blue (check around the lips and fingertips).

If a baby is struggling to breathe but hasn’t turned blue, call for emergency medical assistance immediately or rush to the nearest emergency room. Meanwhile, keep baby warm and as quiet as possible, and in the position he or she seems most comfortable.

If resuscitation seems necessary, survey baby’s condition with Steps 1-2-3:

STEP 1. CHECK FOR UNRESPONSIVENESS

Try to rouse a baby who appears to be unconscious by calling by name loudly, “Hannah, Hannah, are you okay?” several times. If that doesn’t work, try tapping the soles of baby’s feet. As a last resort, try gently shaking or tapping baby’s shoulder—do not shake vigorously, and don’t shake at all if there is any possibility of broken bones or of head, neck, or back injury.

STEP 2. SEEK HELP

If you get no response, have anyone else present call for emergency medical assistance while you continue to Step 3. If you are alone with baby and feel sure of your resuscitation skills, proceed without delay, periodically calling loudly to attract help. If, however, you are unfamiliar with resuscitation and/or feel paralyzed by panic, go to the nearest phone immediately with the baby (assuming there are no signs of head, neck, or back injuries), or better still, bring a cordless or cell phone to baby’s side, and call 911. The dispatcher will guide you as to the best course of action.

Important: The person calling for emergency medical assistance should be certain to stay on the phone as long as necessary to give complete information and until the dispatcher has concluded questioning. The following should be included: name and age of baby; present location (address, cross streets, apartment number, best route if there is more than one route); condition (is baby conscious? breathing? bleeding? in shock? Are there signs of life such as movement or responsiveness?); cause of condition (poison, drowning, fall), if known; phone number, if there is a phone at the site. Tell the person calling for help to report back to you after calling.

STEP 3. POSITION BABY

Move baby as a unit, carefully supporting head, neck, and back as you do, to a firm, flat surface (a table is good because you won’t have to kneel, but the floor will do). Quickly position baby faceup, head level with heart, and use Steps A-B-C (airway, breathing, circulation)1 to survey his or her condition.

A. CLEAR THE AIRWAY

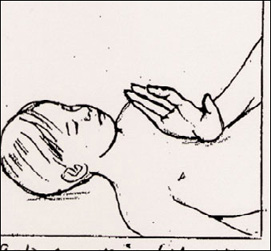

Use the following head-tilt/chin-lift technique to try to open the airway, unless there is a possibility of a head, neck, or back injury. If such an injury is suspected, use the jaw-thrust technique instead.

Important: The airway of an unconscious baby may be blocked by a relaxed tongue or epiglottis or by a foreign object. The airway must be cleared before baby can resume breathing.

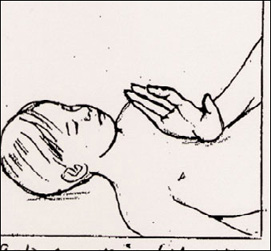

Head tilt/chin lift. Place the hand nearest baby’s head on the forehead and one or two fingers (not the thumb) of the other hand under the bony part of the lower jaw at the chin. Gently tilt baby’s head back slightly by applying pressure on the forehead and lifting the chin. Do not press on the soft tissues of the under-chin or let the mouth close completely (keep your thumb in it if necessary to keep the lips apart). Baby’s head should be facing the ceiling in what is called the neutral position, with the chin neither down on the chest nor pointing up in the air. The head tilt necessary to open the airway in a child over one year may be somewhat greater (the neutral-plus position; see facing page). If the airway does not open in a neutral position, move on to check for breathing (B).

Jaw thrust, for use when neck or back injury is suspected: With your elbows resting on the surface where baby is lying, place two or three fingers under each side of the lower jaw, at the angle where the upper and lower jaw meet, and gently lift the jaw upward to a neutral position (see head tilt, above).

Important: Even if baby resumes breathing immediately, get medical help. Any baby who has been unconscious, has stopped breathing, or has nearly drowned requires medical evaluation.

B: CHECK FOR BREATHING

1. After performing either the head tilt or the jaw thrust, look, listen, and feel for 3 to 5 seconds to see if baby is breathing: Can you hear or feel the passage of air when you place your ear near baby’s nose and mouth? Does a mirror placed in front of baby’s face cloud up? Can you see baby’s chest and abdomen rising and falling (this alone isn’t proof of breathing, since it could mean baby is trying to breathe but isn’t succeeding)?

If normal breathing has resumed, maintain an open airway with head tilt or jaw thrust. If baby regains consciousness as well (and has no injuries that make moving inadvisable), turn him or her to one side. Call for emergency medical assistance now if someone else hasn’t already called. If baby starts to breathe independently, and also starts to cough forcefully, this may be the body’s attempt to expel an obstruction. Don’t interfere with the coughing.

If breathing is absent, or if baby is struggling to breathe and has bluish lips and/or a weak, muffled cry, you must get air into the lungs immediately. Continue below. If emergency medical assistance has not been summoned and you are alone, continue trying to attract a neighbor or passersby.

2. Maintain an open airway by keeping baby’s head in a neutral position (or neutral-plus position, if needed, for a baby over a year) with your hand on the forehead. With a finger of the other hand, clear baby’s mouth of any visible vomit, dirt, or other foreign matter. Do not attempt a sweep if nothing is visible.

Important: If vomiting should occur at any point, immediately turn baby to one side, clear mouth of vomit with a finger, reposition baby on back, and quickly resume rescue procedures.

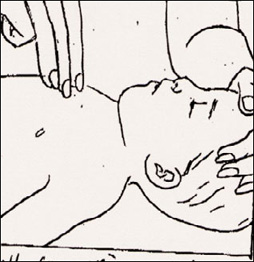

3. Take a breath through your mouth and place your mouth over baby’s mouth and nose, forming a tight seal (see illustration below). With a baby over a year old, cover just the mouth, and pinch the nostrils closed with the fingers of the hand that is keeping the head tilted back.

4. Blow two light, slow breaths of 1 to 1½ seconds each into baby’s mouth, pausing between them to turn your head slightly and take a breath. Observe baby’s chest with each breath. Stop blowing when the chest rises, and wait for the chest to fall before beginning another breath. In addition, listen and feel for air being exhaled.

In rescue breathing for infants, both mouth and nose must be covered.

Important: Remember, a small baby needs only a small amount of air to fill the lungs. Though blowing too lightly may not expand the lungs fully, blowing too hard or too fast can force air into the stomach, causing distension. If at any point during rescue breathing baby’s abdomen becomes distended, don’t try to push it down—this might cause vomiting, which could present the risk of vomit being aspirated, or inhaled, into the lungs. If the distension seems to be interfering with chest expansion, turn baby to one side, head down if possible, and apply gentle pressure to the abdomen for a second or two.

5. If the chest does not rise and fall with each breath, readjust the head-tilt/chin-lift (or jaw-thrust) position and try two more breaths. Blow a bit harder if necessary. If the chest still does not rise, it is possible that the airway is obstructed by food or a foreign object—in which case move quickly to dislodge it, using the procedure in When Baby Is Choking on page 589.