THE most accessible of Blake’s poems are the Songs of Innocence, intended to be read aloud by adults to small children, and embedded in images that enrich the texts. Some of these are simple illustrations, but others differ suggestively from the words, hinting at perspectives that adult readers may ponder while the children receive a simpler message. More than in his illustrations for other poets, Blake was developing symbolic ideas that were very much his own, but the same techniques of “reading” the images are called into play.

Containing just twenty-three short lyrics, Songs of Innocence was first printed in 1789, five years before being reissued with a set of companion poems as Songs of Innocence and of Experience. The combined volume, in which four of the earlier poems were moved to Experience, is subtitled Showing the Two Contrary States of the Human Soul. Experience complements Innocence rather than supplanting or refuting it, for Innocence has a hopefulness and sense of trust that it is crucial not to lose. “Innocence dwells with wisdom,” Blake later wrote, “but never with ignorance.”1

The early biographer Alan Cunningham said that “the original genius of Blake was always confined through poverty to small dimensions.” Copper was indeed expensive, and the plates were just three inches by five, but that was not necessarily a drawback. The format suited the engraving style in which he had been trained, and large plates might have diminished his intensity of focus. An art historian comments, “Blake was a miniaturist, a jeweler in his colouring, always preferring the small-scale. The movement in his art always comes from the wrist, never from the shoulder.”2

The jewel-like effect is vividly apparent in the title page, reproduced here from the late copy Z, printed in 1826 for Blake’s friend Henry Crabb Robinson and now in the Library of Congress (color plate 3). At the knee of their mother or nurse, a little boy and girl are gazing at the pictures that accompany the words. Behind them a tree laden with apples supports a climbing vine, a traditional symbol for children sustained by adults. The word “Innocence” flows in a graceful cursive script, and “songs” bursts out in leaves.

For a parent, aware of the bleak truths of Experience, the situation is poignant. “Reassuring gestures and words experienced in early childhood,” the sociologist Peter Berger says, “build in the child a fundamental trust in the world. Yet speaking empirically, this trust is misplaced, is an illusion. The world is not at all trustworthy. It is a world in which the child will experience every sort of pain, and it is a world that in the end will kill him.” The apples hanging above the mother and children may hint at the tree of knowledge—knowledge that will be acquired all too soon.3

William and Catherine Blake never had a child, and we don’t know how much unhappiness that may have caused. In any event, the Songs of Innocence were clearly written by someone deeply sympathetic to children, and in this they differ greatly from the publications for children that were widely consumed at the time. Some of those took a stern line on childish wickedness, as in a hymn by Isaac Watts:

O Father, I am but a child,

My body is made of the earth,

My nature, alas! is defiled,

And a sinner I was from my birth.

John Wesley, cofounder of Methodism, instructed parents, “Whatever pains it costs, break the will if you would not damn the child. Let a child from a year old be taught to fear the rod and to cry softly; from that age make him do as he is bid, if you whip him ten times running.”4 The child should cry softly because loud cries would provoke further thrashing.

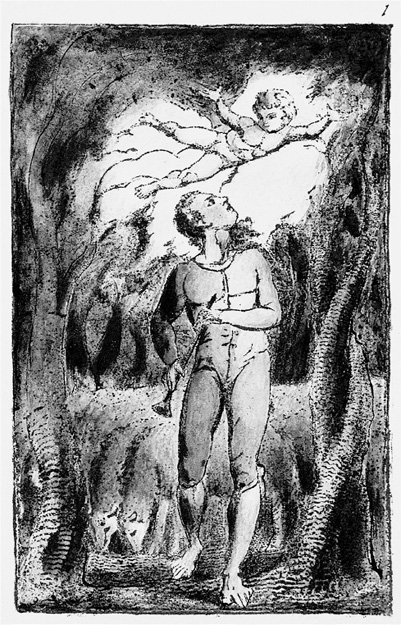

13. Songs of Innocence, frontispiece, copy L, plate 1

Progressive books for children did exist, but although no longer obsessed with hellfire, they were just as didactic in their own way. A typical title was The History of Tommy Playlove and Jacky Lovebook: Wherein Is Shown the Superiority of Virtue over Vice; another was Fables in Monosyllables, by Mrs. Teachwell, to Which Are Added Morals, in Dialogues, between a Mother and Children.5 Blake wants to challenge and inspire children, not preach, and his world of Innocence is filled with beauty, tenderness, sympathy, and joy.

The title page of Songs of Innocence is not the actual first plate. Preceding it comes a remarkable frontispiece (figure 13) in which a musician gazes up at a soaring child, framed by trees and with sheep grazing in the background. The mother and children on the title page were clothed, but Blake’s more overtly symbolic figures are usually naked or wear diaphanous garments, in accordance with his conviction that in a good painting “the drapery is formed alone by the shape of the naked body.”6

Since there are no words in this frontispiece, it invites us to ponder whatever the image may suggest. The poem entitled Introduction on the third plate (not reproduced here) clarifies what we were seeing in the frontispiece:

Piping down the valleys wild,

Piping songs of pleasant glee,

On a cloud I saw a child,

And he laughing said to me:

“Pipe a song about a lamb;”

So I piped with merry cheer;

“Piper pipe that song again,”

So I piped, he wept to hear.

“Drop thy pipe, thy happy pipe,

Sing thy songs of happy cheer.”

So I sung the same again

While he wept with joy to hear.

“Piper sit thee down and write

In a book that all may read—”

So he vanished from my sight,

And I plucked a hollow reed.

And I stained the water clear,

And I wrote my happy songs

Every child may joy to hear.

Judging from references in poems further on, the lamb is suggestive of the Lamb of God. Weeping here expresses joy, not grief, as in one of the Proverbs of Hell in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “Excess of sorrow laughs, excess of joy weeps.”7

Floating above the piper’s head in the frontispiece, the visionary child tells him what his song should be. First comes melody alone, then melody with words, and finally words that are written down, using natural materials. And then the airborne child vanishes, leaving the poem on the page as his gift. It is the gift of the musician-poet too. On the title page a miniature piper is shown leaning against the sloping “I” of the word “Innocence.”

When Blake called these lyrics songs, he meant it literally. Someone who knew him recalled that he used to compose his own tunes, “and though, according to his confession, he was entirely unacquainted with the science of music, his ear was so good that his tunes were sometimes most singularly beautiful, and were noted down by musical professors.” Alas, none of their transcriptions have survived, but in all likelihood Blake’s melodies would have resembled the hymns and folk songs that he loved. Another writer reported that he liked to compose in all three arts simultaneously: “As he drew the figure he meditated the song which was to accompany it, and the music to which the verse was to be sung was the offspring too of the same moment.”8

An expression of Innocence at its simplest is a rhapsodic little lyric entitled Infant Joy:

“I have no name;

I am but two days old.”

What shall I call thee?

Joy is my name.”

Sweet joy befall thee!

Pretty joy!

Sweet joy but two days old,

Sweet joy I call thee;

Thou dost smile;

I sing the while,

Sweet joy befall thee.9

Unobtrusively, Blake varies the stresses from the regular underlying beat:

Thóu dost smíle.

I síng the while,

Swéet jóy befáll thee.

The language has the extreme simplicity of childish speech or of traditional nursery rhymes, which Dylan Thomas says that he loved before he was old enough to understand them: “I had come to love just the words of them, the words alone. . . . And as I read more and more, my love for the real life of words increased until I knew that I must live with them and in them, always.”10

In any effective lyric, rhythm is as important as verbal meaning. Blake occasionally uses anapests, in which an accented syllable is preceded by two unaccented ones. If used without variation, it can sometimes sound too bouncy for serious verse, as in a poem Blake knew, William Cowper’s The Poplar Field:

Twelve years have elapsed since I last took a view

Of my favourite field and the bank where they grew,

And now in the grass behold they are laid,

And the tree is my seat that once lent me a shade.

By shortening the line length in another poem, The Ecchoing Green, Blake gives anapests an elegiac resonance:

Old John with white hair

Does laugh away care,

Among the old folk.

They laugh at our play,

And soon they all say,

“Such such were the joys

When we all girls and boys

In our youth time were seen

On the echoing green.”11

That rosy impression of community is proper to the mood of Innocence, although in hindsight it will look different. George Orwell entitled his searing memoir of life in an abusive boarding school “Such, Such Were the Joys.”

Simple as Infant Joy is, the ecstatic baby talk departs from fact, for as Coleridge reprovingly noted, a two-day-old baby doesn’t smile. The age is symbolic. It was customary to baptize an infant on the third day after birth, at which moment the parents would confer its name. So at this point the infant is absolutely innocent and gets to name herself—Joy is a girl’s name—in the immediacy of her happiness, while her mother foresees the future and can only hope that sweet joy will continue to befall her.12

The ravishing picture (color plate 4) is self-evidently symbolic. Copy Z, reproduced here, is the very one that Coleridge saw and admired in the last year of Blake’s life. Seated in a huge open blossom are a mother and child with a winged figure facing them, unmistakably recalling paintings of the Virgin Mary adoring the Christ child. But Blake despised the theological doctrine that Mary was a virgin, and liked to suggest that if Joseph didn’t get her pregnant, somebody else must have.

And what flowers are these? They are anemones, sacred in classical lore to Venus, supposedly stained red by the blood of the dying Adonis. It was a recent revelation in botany that plants have sex, and Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles) published an immensely popular poem called Loves of the Plants. Darwin’s language is unabashedly erotic:

With honeyed lips enamoured woodbines meet,

Clasp with fond arms, and mix their kisses sweet.

In Darwin’s poem the anemone, recalling the association with Venus’s grief, is a victim of autumnal frost:

All wan and shivering in the leafless glade

The sad Anemone reclined her head;

Grief on her cheeks had paled the roseate hue,

And her sweet eyelids dropped with pearly dew.13

Blake was interested in Loves of the Plants, and in Songs of Innocence flowers participate in a sexual energy that human beings share with the rest of nature. Commentators have suggested that the maternal blossom in Infant Joy is meant to look womblike and the drooping bud below it phallic. Throughout Innocence there are further hints of sexuality, along with references to stroking, playing, licking, kissing, and touching. In Visions of the Daughters of Albion a few years later, the feminist character Oothoon exclaims, “Infancy, fearless, lustful, happy! nestling for delight / In laps of pleasure.” As for the winged figure in the Infant Joy picture—the dotted wings seem more insectlike than angelic—that is probably Psyche, symbol of the immortal spirit, as in A Sunshine Holiday.14

Since the poems express multiple facets of Innocence, there is no correct order in which to read them. Twenty copies of Songs of Innocence still exist for which the original sequence is known (Blake and his wife sewed the pages together with simple paper covers, to be rebound by purchasers later on). Remarkably, the sequence is uniquely different in each.15 Infant Joy sometimes appears near the beginning of the book, sometimes almost at the end. Another poem, The Blossom (color plate 5), usually appears at some distance from it, but visually they have much in common. Again we see a mother and infant, but this time she has wings, and little winged beings are dancing and soaring around. The mother and child are seated on what is evidently some form of vegetation, but it surges with extraordinary energy and resembles no actual plant. David Erdman’s description has caught on: it is a flame-flower. One may think of Dylan Thomas’s line, “The force that through the green fuse drives the flower.”16

The text is like a riddle.

Merry merry sparrow

Under leaves so green

A happy blossom

Sees you swift as arrow

Seek your cradle narrow

Near my bosom.

Pretty pretty robin

Under leaves so green

A happy blossom

Hears you sobbing sobbing

Pretty pretty robin

Near my bosom.

What is going on, spoken by the blossom itself? A merry sparrow flies down to a nest that is described, in terms a small child can understand, as its cradle. As for the pretty robin, it is not merry at all, for it sobs. Very likely an allegory of birth is implied, and the sobs express the pains of childbirth—pain even in joy. One of Blake’s made-up proverbs is “Joys impregnate. Sorrows bring forth.”17 The sparrow and robin might also represent two aspects of a small child’s mood, sometimes nestling and content, at other times sobbing. It may seem surprising that neither bird actually appears in the picture, but it is characteristic of Blake to emphasize symbolic significance, not literal imagery. The focus is on the speaking blossom.

If the figures surrounding the mother and child can be seen as a sequence moving clockwise from left to right, then the ones embracing above her head might symbolize the sexual union that will lead to birth, while the final figure, holding up wingless arms as it drops from the air, is a cherub about to be born. Such an interpretation makes sense, but others do too. “We may think of the five winged joys,” Erdman suggests, “as the aroused senses, capable of soaring, and the wingless but actually soaring boy as the imagination or genius.” We may also be reminded of the infant Jesus and his mother. In a few late copies, a white sun shines out from behind the mother’s head, surrounding it like a halo.18

Might the sobbing of the robin make the listener think also of a familiar nursery rhyme?

Who killed Cock Robin?

“I, said the sparrow,

With my little bow and arrow,

I killed Cock Robin.”

Innocence is trusting, but it is not ignorant of death, which was all too frequent for the very young in Blake’s day.

Blake is sometimes referred to as a Cockney, but there is no evidence that he had a specifically Cockney pronunciation (“hartist” for “artist,” and so on). By looking at his rhymes, however, it is possible to get some notion of how he did pronounce words, and he often heard exact rhymes where we no longer do. “Poor” rhymes with “more, “devil” with “civil,” and “creature” with “later” (like the American “critter”). Since he left off the final “g” in words that ended in “ing,” “sobbing” did indeed rhyme with “robin.”19

Still another sweetly simple lyric, The Lamb, explicitly invokes a religious theme:

Little lamb who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

Gave thee life and bid thee feed

By the stream and o’er the mead;

Gave thee clothing of delight,

Softest clothing wooly bright;

Gave thee such a tender voice,

Making all the vales rejoice!

Little lamb who made thee?

Dost thou know who made thee?

Little lamb I’ll tell thee:

He is callèd by thy name,

For he calls himself a lamb:

He is meek and he is mild,

He became a little child:

I a child and thou a lamb,

We are callèd by his name.

Little lamb God bless thee.

Little lamb God bless thee.20

It is the child who speaks, catechizing the lamb—“Little lamb I’ll tell thee.” The God who protects the world of Innocence is the Jesus who was born a little child, not a patriarch far off in heaven.

The picture accompanying The Lamb (figure 14) has a comfortable realism very different from the symbolic intensity of Infant Joy and The Blossom. The text nestles within an arch formed by sinuous trees, wreathed in vines and tendrils. A flock of sheep has gathered at the door of the thatched cottage, and a naked boy holds out his hand for a lamb to lick. A pair of white birds, lovebirds perhaps, perch at the far end of the roof. In some copies a green lawn fills the bottom of the picture; in others a stream of blue water is flowing there. It is sometimes suggested that the trees look fragile, implying that their protection may not last, but at any rate the immediate impression is of security and trust, which is certainly reinforced by the massive shade tree in the background.

This is not to say that Innocence possesses an adequate understanding of existence. In a much later poem Blake asks,

Why is the sheep given to the knife? the lamb plays in the sun;

He starts! he hears the foot of man! he says, “Take thou my wool,

But spare my life;” but he knows not that winter cometh fast.21

In winter the lamb will lament the loss of its wool, transformed into garments to keep humans warm. And lambs as well as sheep often end up as dinner.

At various places in Songs of Innocence there are intimations of the threatening aspects of life. On Another’s Sorrow hints at the Crucifixion when it explains why Jesus is able to empathize with human suffering:

14. The Lamb, Songs of Innocence, copy L, plate 24

He becomes an infant small.

He becomes a man of woe;

He doth feel the sorrow too.22

He feels the sorrow because he is a man of sorrows himself.

In most of these poems any ambiguities are deeply buried, but a few embody a double message very clearly: the consoling one that small children need to hear, and another that reflects adult perspective. In one such poem, a little black boy hopes that an English boy can learn to love him despite his dark skin, but imagines having to wait for a heaven in which his skin too will be white. In another, poor children who were being educated in charity schools file into Saint Paul’s Cathedral for an annual service of thanksgiving:

Now like a mighty wind they raise to heaven the voice of song,

Or like harmonious thunderings the seats of heaven among.

Beneath them sit the aged men, wise guardians of the poor;

Then cherish pity, lest you drive an angel from your door.

There is an echo of the Book of Revelation: “I heard as it were the voice of the great multitude, and as the voice of many waters, and as the voice of mighty thunderings.” And perhaps there is an echo as well of the Epistle to the Hebrews: “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.”23

This may sound positive, but as Blake well knew, conditions in charity schools were truly dreadful, and the last line can therefore be read as grimly ironic. Far from cherishing pity, these “wise guardians” will send their wards right back to labor in exploitative workhouses. A small child, listening to the poem, will take in the positive message, but an adult will notice what has been described as the “latent presence of Experience within Innocence.”24

One poem especially, The Chimney Sweeper, brings this double perspective into the open.

When my mother died I was very young,

And my father sold me while yet my tongue

Could scarcely cry “weep weep weep weep,”

So your chimneys I sweep and in soot I sleep.

There’s little Tom Dacre, who cried when his head

That curled like a lamb’s back was shaved, so I said,

“Hush Tom never mind it, for when your head’s bare,

You know that the soot cannot spoil your white hair.”

And so he was quiet, and that very night,

As Tom was a sleeping he had such a sight,

That thousands of sweepers, Dick, Joe, Ned and Jack,

Were all of them locked up in coffins of black,

And by came an angel who had a bright key,

And he opened the coffins and set them all free.

Then down a green plain leaping laughing they run

And wash in a river and shine in the sun.

Then naked and white, all their bags left behind,

They rise upon clouds, and sport in the wind.

And the angel told Tom if he’d be a good boy,

He’d have God for his father and never want joy.

And so Tom awoke and we rose in the dark

And got with our bags and our brushes to work.

Though the morning was cold, Tom was happy and warm,

So if all do their duty, they need not fear harm.25

The condition of chimney sweeps was horrendous, and a campaign to do something about it produced a stream of books and pamphlets that make harrowing reading. The usual age to start an apprenticeship, as in Blake’s own case, was thirteen, but by then a boy would be too large to squeeze into narrow, crooked chimneys. He—very occasionally she—would therefore begin work by the age of seven, and sometimes as young as four. “My father sold me” is literally correct. Parents normally paid a master a premium in return for the skills he would teach, as Blake’s parents did with the engraver Basire, but in this horrible trade it was the master who paid the parents. The children suffered injuries of all kinds, such as twisted joints and spines, and since there were no facilities for washing off soot, cancer of the scrotum was common. They were often required to be naked while they worked, lest clothing catch on the rough plaster with which chimneys were lined.26

A bill was passed in Parliament in 1788, one year before Songs of Innocence, to prohibit apprenticeship of boys younger than eight, and it required that they bathe once a week, though without specifying how facilities for that were to be provided. Just how callously young sweeps were treated is indicated by another provision: that they should no longer be forced to go up ignited chimneys. Even that modest attempt at reform was never enforced, and employing small children as chimney sweeps did not become illegal until 1875.27

Yet Blake’s poem is remarkable, as Heather Glen observes, for avoiding any explicit note of protest. The speaker accepts it as simply inevitable that because his mother died, his father sold him when he was still too little to pronounce the cry of “Sweep!” in search of work. “Weep weep weep weep” is a poignant lamentation. And there is a casual but telling challenge to the reader: “So your chimneys I sweep and in soot I sleep.” The children did indeed sleep on bags they had filled with soot.28

The plight of injured innocence is evoked by a hint of rural imagery in Tom’s hair “that curled like a lamb’s back,” recalling the loving trust in The Lamb. The older boy clearly knows that he’s offering a consoling rationalization when he says that shaving Tom’s blond curls will make it easier to keep his head clean. But the last line of the poem is a much more insidious rationalization that the older boy himself has internalized: “So if all do their duty, they need not fear harm.” The implication is that if they ever slack off for a moment, punishment will promptly follow. And the still more chilling implication is that they are doing their appalling duty, yet even so they experience harm every day of their lives—with the further threat that if they should ever fail to do that duty, God will refuse to be their father.

The picture that accompanies this poem (color plate 6) is strangely minimal. The text fills up nearly the whole page, and the boys running toward the river are tiny stick figures at the very bottom, where an angelic figure stoops to help the smallest one out of a coffin—a dream version of the claustrophobic chimneys. Blake was perfectly capable of using two plates for a poem when he wanted to; evidently the congested effect here was deliberate. Zachary Leader offers a persuasive interpretation: “The scene lacks the very qualities the sweeps most long for: open spaces, sun, warmth, clear bright colors. The great block of text presses down upon Tom’s dream like a weight, stunting and crushing it, much as Innocence itself is ground down by a life of poverty and oppression.”29 In a few copies, however, the effect is startlingly different. As in the one reproduced here, the sky is suffused with golden light, and the stooping figure has a bright halo around his head. That is the Jesus of Innocence, fully human as well as divine.

Institutional religion serves here as ideology, inculcating a coercive message about obedience and duty. Still, it is not “false consciousness” in the negative Marxist sense. The consolation that the boys feel is very real, and their lives would be even more miserable if it were taken away from them. Little Tom’s dream is likewise a desperately needed refuge from too much reality. By day the boys may cry “Weep weep weep weep”; in dreams they can wash themselves clean and leap in the sun.30

To illustrate Blake’s wide range of reference, Kathleen Raine points to a passage in Emanuel Swedenborg, the self-styled prophet whose works Blake read and annotated:

There are also spirits amongst those from Jupiter, whom they call Sweepers of Chimneys, because they appear in like garments, and likewise with sooty faces. . . . One of these spirits came to me, and anxiously requested that I would intercede for him to be admitted into heaven. . . . At that instant the angel called to him to cast off his raiment, which he did immediately with inconceivable quickness from the vehemence of his desire. . . . I was informed that such, when they are prepared for Heaven, are stripped of their own garments and are closed with new shining raiment, and become angels.31

This is the Neoplatonic concept of the body as a temporary covering for the immortal spirit, which Swedenborg thought of as a wholly positive symbolism. In Blake’s poem it is grimly ironic, since he does not believe in waiting for an afterlife to compensate for the sufferings of this one.

Rationalization of what cannot be avoided is not the same thing as willing acceptance, and some aphoristic verses in Blake’s notebook, collected under the title Auguries of Innocence, are keenly expressive of cruelty and injustice.

A robin red breast in a cage

Puts all Heaven in a rage;

A dove house filled with doves and pigeons

Shudders Hell through all its regions.

A dog starved at his master’s gate

Predicts the ruin of the state;

A horse misused upon the road

Calls to Heaven for human blood.32

The plain meaning of the first lines is that robins fly free and ought not to be caged, whereas domesticated doves come home willingly to their dovecotes. But the reason Hell shudders may be that the harmonious friendship of humans and doves is only apparent—people kept doves in order to eat them. There are religious echoes as well. In folk tradition, the robin got its red breast—much redder in the little British robin than in the American thrush also called by that name—for having done a kindness to Jesus on the cross. And Hell shuddered with earthquake when Jesus harrowed it to redeem the souls of the just.33

Innocence, as Blake imagines it, is trusting but not naïve, inexperienced but already anticipating immersion in Experience. He was apparently willing to sell separate copies of Songs of Innocence to purchasers who didn’t want Songs of Experience, but in the combined Songs he achieves an extraordinary extension of imaginative insight. And with few exceptions, the poems in the second set are ones that nobody would want to read to small children.