WITH Songs of Experience—clearly aimed at adults, not children—we enter an altogether different imaginative world, one haunted by loneliness, frustration, and cruelty. Sometimes a poem in the second series corresponds directly to one in the first; there is a Chimney Sweeper in both sets, and The Tyger makes a direct allusion to The Lamb. For other poems, the brilliant London for example, there is no corresponding poem in Innocence, whose imagery is usually rural rather than urban.

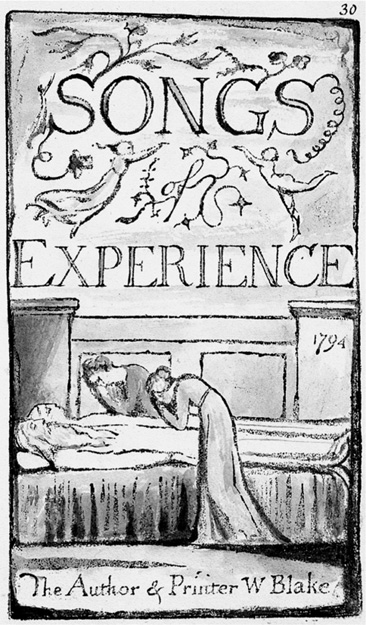

Songs of Experience has a separate title page of its own (figure 15) that shows leaves and tendrils sprouting from “songs,” but the stiff block letters of “experience” might be chiseled on a tombstone, and indeed, two mourners bend over bodies or funerary effigies that probably belong to their parents. Experience may believe that death is final, but Innocence is more hopeful, and the little figures in the air suggest that the spirit does not perish with the mortal body. That is not to say, though, that Innocence is entirely right. Blake did believe that the human spirit lives on, but not in the orthodox sense of reanimation in an otherworldly heaven altogether different from the life we know. In Europe, published in the same year as Songs of Experience, he contemptuously called that heaven “an allegorical abode where existence hath never come.”1

The frontispiece for Songs of Experience (figure 16) echoes, but also contrasts with, the one in Innocence. In this one the man no longer carries a musical instrument, the sheltering bower has been replaced by a thick trunk close by and another tree far away, and the winged child is seated oddly on the man’s head. Are the child’s hands being held to help him balance there or to prevent his escape? Both man and child stare directly at us, with expressions that are hard to read—questioning? coolly challenging? In some copies the sky glows golden, in others red, suggesting that the sun has set. The landscape in this frontispiece seems barren, and the flock of sheep has been replaced by two, or possibly three, grazing in a single shadowy mass.

15. Songs of Experience, title page, copy L, plate 30

16. Songs of Experience, frontispiece, copy L, plate 29

There is also a new title page for the combined volume (color plate 7), and in this one Experience is dominant. Fig leaves conceal the genitals of a couple who are prostrating themselves and are unmistakably Adam and Eve just after eating the forbidden fruit. Sex, which was innocent before the Fall, now provokes shame, and flames of divine wrath blaze above. But since Blake rejected the concept of original sin, the guilt must be their own projection, and so are the punitive flames. In Blake’s view, the story in Genesis that an angel was stationed to bar the reentry of Adam and Eve into Paradise is likewise false. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, probably printed in 1793, a year before Songs of Experience, he proclaims, “The cherub with his flaming sword is hereby commanded to leave his guard at the tree of life.”2 If Adam and Eve have been expelled from Paradise, it is because they mistakenly expelled themselves.

There is an explicit counterpart to Infant Joy in Songs of Experience, entitled Infant Sorrow.

My mother groaned! my father wept.

Into the dangerous world I leapt:

Helpless, naked, piping loud,

Like a fiend hid in a cloud.

Struggling in my father’s hands,

Striving against my swaddling bands,

Bound and weary I thought best

To sulk upon my mother’s breast.

All of the sounds are distressing: a mother groaning in childbirth, a father weeping (at her anguish?), and a newborn infant squalling like an alarming fiend. In the earlier poem “joy” was an emotion and also a name. “Sorrow” here is not an identity, just a condition of sadness and pain, and the infant might be either male or female. After its spirited leap into the dangerous world, it finds itself frustrated by helplessness and confined in swaddling clothes. The only choice open to it is “to sulk upon my mother’s breast.”3

The picture (figure 17) is ambiguous. Does it suggest maternal love or maternal control? Beneath heavy curtains, the child—bigger and more robust than an actual newborn—seems to be recoiling from the mother rather than reaching out. Her expression is sternly determined, perhaps irritated. Though the room is well furnished and comfortable, this is indeed going to be a dangerous world, and from the very outset the child is conscious of threatening emotions that are very different from the mood of Infant Joy.

Fathers were barely visible in Innocence. In Experience they are patriarchs who impose repression even when they mean well. A Little Girl Lost begins with a vehement declaration:

Children of the future age,

Reading this indignant page,

Know that in a former time

Love! sweet love! was thought a crime.

Then comes a frank celebration of nakedness:

In the age of gold,

Free from winters cold,

Youth and maiden bright

To the holy light

Naked in the sunny beams delight.

They dally innocently in a garden, like an unfallen Adam and Eve, and agree to meet again at nightfall. But the patriarch intervenes:

17. Infant Sorrow, Songs of Experience, copy L, plate 39

Came the maiden bright;

But his loving look,

Like the holy book,

All her tender limbs with terror shook.

“Ona! pale and weak!

To thy father speak:

O the trembling fear!

O the dismal care!

That shakes the blossoms of my hoary hair.”

It is a loving father who creates guilt, blaming the daughter for provoking his own fear, and recalling the “holy book” that teaches guilt for sin. According to Saint Paul that is precisely what the Bible is for: “I had not known sin, but by the law: for I had not known lust, except the law had said, Thou shalt not covet.”4

Institutional religion, Blake thought, had a wicked commitment to promoting sexual repression. Innocence exists in a world of nurturing gardens; Experience is haunted by memories of the lost garden from which Adam and Eve were ejected—or ejected themselves.

I went to the garden of love,

And saw what I never had seen:

A chapel was built in the midst,

Where I used to play on the green.

And the gates of this chapel were shut,

And “thou shalt not” writ over the door;

So I turned to the garden of love

That so many sweet flowers bore.

And I saw it was filled with graves,

And tombstones where flowers should be,

And priests in black gowns were walking their rounds,

And binding with briars my joys and desires.5

The picture (not reproduced here) shows an open grave and a boy and girl kneeling nearby in prayer while a monk reads from a black book.

Another garden poem suggests how deeply repression can be internalized.

Ah sunflower! weary of time,

Who countest the steps of the sun:

Seeking after that sweet golden clime

Where the traveler’s journey is done;

Where the youth pined away with desire

And the pale virgin shrouded in snow

Arise from their graves and aspire

Where my sunflower wishes to go.6

Sunflowers are heliotropes, turning to follow the moving sun across the sky, and therefore weary of time in a cycle that never ends. The frustrated youth and the pale virgin are wasting their lives in needless self-denial, waiting for eventual reward in an unreal heaven instead of seizing pleasure here and now.

These poems may suggest that a hopeful resolution could still be possible, but a central theme throughout Blake’s work is the persistent conflicts that seem inseparable from sexuality. One of the most memorable Songs of Experience, just eight lines long, is filled with disturbing implications. It has, Harold Bloom says, the “ruthless economy of thirty-four words.”

O rose, thou art sick.

The invisible worm

That flies in the night,

In the howling storm,

Has found out thy bed

Of crimson joy,

And his dark secret love

Does thy life destroy.

The picture (color plate 8) shows a crimson blossom bent down to the ground, with a worm wriggling into it while a terrified female figure tries to escape. Above, a caterpillar is feeding, and two more females—withered blossoms, perhaps—huddle on bare stems. The big thorns are no help in protecting the rose from blight. A critic comments, “Attack is a worm’s form of ‘love.’”7

However one chooses to interpret this enigmatic poem, it is clearly concerned with corrosive sexual guilt, and also with the excitement that taboo and secrecy provoke. Roses were an age-old symbol for the transitory nature of beauty, as in Robert Herrick’s “Gather ye rosebuds while ye may.” In addition Blake is likely to have had two recent texts in mind. One is scribbled by the heroine of Samuel Richardson’s popular novel Clarissa, after realizing that her frustrated seducer had raped her while she was drugged unconscious: “Thou pernicious caterpillar, that preyest upon the fair leaf of virgin fame, and poisonest those leaves which thou canst not devour! . . . Thou eating canker-worm that preyest upon the opening bud, and turnest the damask rose into livid yellowness!”8 Convinced that she has been defiled, even though against her will, Clarissa wastes away and dies as a saint who is too good for this world.

The other text is a jeu d’esprit by Matthew Prior entitled A True Maid (“maid” meaning “virgin”):

“No, no; for my virginity,

When I lose that,” says Rose, “I’ll die.”

“Behind the elms last night,” cried Dick,

“Rose, were you not extremely sick?”9

This is a girl who is literally named Rose, and she has escaped the fate worse than death, but just barely—the poem is a knowing dirty joke, with an aptly named Dick. Blake evidently had the inspiration of taking Prior’s last line and making it his first: “O Rose, thou art sick.” The implication is that there is something very wrong with a culture that chuckles at Prior’s sly innuendo.

In Blake’s poem, who is saying, “O Rose, thou art sick”? Unlike the other Romantics, he rarely uses a confessional first-person style. His lyrics reflect what Susanne Langer calls “impersonal subjectivity,” as in hymns, where a whole congregation can sing, “Jesu, lover of my soul.”10 Richardson’s Clarissa is a character in a realistic narrative; Prior’s Rose and Dick are protagonists in a joke. Blake’s poem is about universal experience.

Goethe does something similar in the remarkably “Blakean” Heidenröslein (Little Heath Rose), which was set superbly to music by Schubert. It needs to be read in the original, because the lyric beauty evaporates in translation. A boy reaches down to pluck a rose, it warns that it will prick, and he plucks it all the same:

Und der wilde Knabe brach

’s Röslein auf der Heiden;

Röslein wehrte sich und stach,

Half ihm doch kein Weh und Ach,

Mußt es eben leiden.

Röslein, Röslein, Röslein rot,

Röslein auf der Heiden.

And the rough boy picked the rose,

Little rose on the heath;

Little rose defended itself and pricked,

No “woe” or “alas” was any use,

It simply had to bear it.

Little rose, little rose, little red rose,

Little rose on the heath.

But Goethe’s poem is tender and sad, acknowledging the way things always are. Blake’s is indignant, indicting the way things are.

The Sick Rose has often been interpreted as a call for sexual liberation. If priests would stop enforcing “thou shalt not,” and if naked love were indulged instead of prohibited, wouldn’t erotic liberation ensue? Blake does sometimes talk that way: “This will come to pass by an improvement of sensual enjoyment.”11 But since the worm is just as much part of nature as the rose, the problem seems deeper than an effect of repressive ideology. And some of the songs of Experience suggest a much darker possibility: that inhibition and frustration are so deeply bound up with sexuality that they are impossible to transcend. That will form a major, even an obsessive, theme in the later poems beyond the Songs.

In another song of Experience the speakers are inanimate objects, presenting contrasting philosophies of life in a symmetrical format.

Love seeketh not itself to please,

Nor for itself hath any care,

But for another gives its ease,

And builds a Heaven in Hell’s despair.

So sang a little clod of clay,

Trodden with the cattle’s feet;

But a pebble of the brook

Warbled out these metres meet:

Love seeketh only self to please,

To bind another to its delight:

Joys in another’s loss of ease,

And builds a Hell in Heaven’s despite.12

Not only are Innocence and Experience contrary states of the soul, but from the perspective of Experience they are irreconcilable. The pebble here is obviously selfish and sadistic, but critics disagree about the clod. Some have argued that it is noble in its self-sacrifice. It is true that selfless love is praised in the first Epistle to the Corinthians, and that according to one of Blake’s Proverbs of Hell, “The most sublime act is to set another before you.” However, a consciously chosen action on someone else’s behalf is very different from continuous self-abnegation, and Blake never approved of turning the other cheek:

Was Jesus humble or did he

Give any proofs of humility?13

It is often assumed that the clod is female and the pebble male, but they could perfectly well be the same sex, if indeed we should see them as gendered at all. And what kind of relationship do they have, if any? Are their two songs going right past each other, or are we overhearing a dialogue? If we do imagine them together, then their relationship would be profoundly sadomasochistic, and Blake can hardly be recommending that. The poem is like a miniature diagram of Les Liaisons Dangereuses, in which a pious woman suffers tragically for giving herself to a narcissistic Don Juan. Bloom says succinctly, “The clod joys in its own loss of ease, the pebble in another’s loss, but there is loss in either case.”14 And if one does imagine a relationship, the clod’s self-abasement might just stimulate the pebble’s selfish desire.

In the picture, once again, Blake neglects to illustrate, inasmuch as the clod and pebble aren’t shown at all (figure 18). We see sheep drinking from a stream, together with two impressively horned bovines. All of them are oblivious of both the clod and the pebble, who are presumably conducting their little psychodrama below. So the hard pebble, just as much as the soft clod, is “trodden with the cattle’s feet.” Meanwhile a duck drifts placidly on the stream, and a frog reposes while another frog jumps into the air with an earthworm beneath. These are creatures at home in their world, as if visitors from pastoral Innocence. But then, the clod and the pebble are at home here too.

Two of the Songs of Experience are masterpieces. The best known, and deservedly so, is The Tyger.

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand dare seize the fire?

And what shoulder, and what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? and what dread feet?

18. The Clod and the Pebble, Songs of Experience, copy Z, plate 32

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And watered heaven with their tears,

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?15

The final stanza is a verbatim reprise of the first—except that contemplating this formidable being has led the speaker to replace “could frame” with “dare frame.”

Alexander Welsh, noting the similar metrical pattern in “Rain, rain, go away, come again another day,” says that Blake has managed to combine “the rhythms of innocent nursery rhymes and game-songs and the rhythms of magical incantation, epiphanic invocation, and prophetic hymn.” The standard poetic meter in English is iambic, stressing every second syllable, as in Milton’s “I may assert eternal Providence / And justify the ways of God to men.” Throwing the accent on the first syllable instead of the second, in trochaic meter, accentuates the stresses as Blake does here. If the phrase “in the forests of the night” appeared in a piece of prose, one would probably hear just two stresses: “in the fórests of the níght.” But cast into pounding trochees, there are four powerful stresses in each line:

Týger Týger búrning bríght

Īn the fórests óf the níght. . . .16

Blake was an exacting reviser. Multiple drafts of The Tyger can be discerned in the notebook known as the Rossetti Manuscript. He once wrote, “Ideas cannot be given but in their minutely appropriate words,” and the pains he took with The Tyger reflect that conviction. In preliminary versions the tiger was conventionally scary. Near the bottom right-hand side of the notebook page reproduced here (figure 19), some almost obliterated lines suggest a really horrible beast:

Could fetch it from the furnace deep

And in thy horrid ribs dare steep

In the well of sanguine woe

In what clay and in what mould

Were thy eyes of fury rolled

Englishmen who had lived in India regularly described man-eating tigers as remorseless. According to the first edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, “The tiger is more ferocious, cruel, and savage than the lion. Although gorged with carnage, his thirst for blood is not appeased; he seizes and tears to pieces a new prey with equal fury and rapacity, the very moment after devouring a former one.” But the tiger in Blake’s poem is no naturalistic beast, and whatever the forests of the night may be, they are not an ordinary Indian jungle. Blake’s tiger dwells in mysterious distant deeps or skies, not on earth at all.17

The companion poem to The Tyger is The Lamb, as is implied in the question, “Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” The Lamb asks a single question that yields a single answer: “Little Lamb, I’ll tell thee.” The Tyger is all questions and no answer, with a driving, accelerating tempo. In The Lamb creation is imagined as a loving gift of life to children and lambs by a God who is himself a shepherd and a lamb. In The Tyger creation gives form to a majestic tiger, a labor that requires titanic daring and strength.

In Genesis, “God said, Let there be light, and there was light.” For creators in Blake’s poems—and he has many versions of them—it is not so effortless as that. Often, as here, they are blacksmiths heating resistant material to be hammered into shape. The chain probably refers to the vertebrae, and the product is organic as well as metallic, with twisted sinews for the beating heart.

Critics who look for irony in Blake’s poems sometimes claim that the speaker of this one is deluded, foolishly worshipping a phantom of his own imagination. But the awesome power of the tiger’s creator simply cannot be dismissed. The questions are challengingly open, for as David Fuller says, “The poem wonders at; it does not explain or expound.”18

19. Manuscript page from Blake’s Notebook

Not only does The Tyger question what kind of creator makes predators as well as their prey, it hints as well at other myths that suggest further lines of questioning. Intoxicated by the driving verse, readers may not stop to ask what is meant by “When the stars threw down their spears / And watered heaven with their tears.” The spears are presumably rays of starlight, and they also recall the weapons of the fallen angels in Paradise Lost, cast down after the Almighty crushed their rebellion; it is their bitter weeping that waters heaven. A clear hint in The Tyger does indeed point to Satan as the creator in the poem. “On what wings dare he aspire” recalls his flight through chaos to destroy the newly created Adam and Eve, as narrated by Milton: “Now shaves with level wing the deep, then soars / Up to the fiery concave towering high.”19 Blake knew Paradise Lost practically by heart, argued with it throughout his life, and eventually summoned Milton back to earth to unite with him in a poem called Milton.

In Blake’s wonderfully condensed lyric, yet another rebel is invoked in “What the hand dare seize the fire?” The striking resemblance of Prometheus to Satan was well known to the early Church fathers. Zeus punished Prometheus with eternal torture for disobeying the commandment that no god should give the gift of fire—in effect, civilization—to the human race. Not surprisingly, Christian theologians held that Prometheus was right to rebel whereas Satan was wrong. For Blake, however, both rebellions are equally justified, since in his opinion the God of Genesis is just as tyrannical as Zeus. That is why Blake claims in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell that “Milton was a true poet, and of the Devil’s party without knowing it.”20 Milton rebelled against the earthly tyrant Charles I, but in Blake’s view, he tried in vain in Paradise Lost to justify the tyranny of a patriarchal God.

This doesn’t mean that Blake was a Satanist. His meaning is that Christian doctrine has confused two very different things, wrongly calling them both by the name of Satan. One is resistance to tyranny, whereas the other is sadistic cruelty. The Satan who revenges himself on God by tempting Adam and Eve to sin has nothing in common with the heroic rebel at the beginning of Paradise Lost. Blake thought it outrageous to believe that an omnipotent, all-knowing God could first prohibit the fruit of knowledge and then allow an immensely powerful fallen angel to tempt the just-created Adam and Eve to pluck it and incur damnation.

Finally, what is one to make of the picture of the tiger? Although in the original format it would be seen simultaneously with the text, it strikes most viewers as bizarrely incongruous. In addition, it differs markedly from one copy to another, depending on how it is colored and how the tiger’s expression is rendered. In the first of the two copies reproduced here (color plate 9), the scene is dark and rather ominous. In the second (color plate 10), the wide-eyed tiger looks merely anxious or bemused, in a bright daytime scene—hardly forests of the night. Erdman describes the single tree as “scared leafless.” This tiger is certainly not burning bright, and there is nothing to suggest fearful symmetry.21

Many commentators have complained that the image is miserably inadequate to the poem; one calls this tiger “mild and silly,” another “simpering.” It has even been suggested that Blake wasn’t any good at drawing animals, but that’s absurd. He was perfectly capable of drawing fierce tigers, and there are two of them in a page of his notebook.22

There is another possibility. From the perspective of Experience, whatever seems overwhelming in existence should arouse fear and awe. Innocence sees it differently. Not only did the same God make tigers and lambs, but both of them inhabit the world we live in. Predators exist that seek to kill us, just as we ourselves kill trusting sheep and lambs. But an animal that can suggest nature as threat may also symbolize nature as our proper home. In a beautiful lyric in Songs of Innocence called Night, “wolves and tygers howl for prey,” but a tender lion stands guard:

And there the lion’s ruddy eyes

Shall flow with tears of gold,

And pitying the tender cries,

And walking round the fold:

Saying “Wrath by his meekness

And by his health, sickness,

Is driven away

From our immortal day.”23

The Tyger doesn’t answer the questions it poses. The picture reminds us that there can be more than one way of trying to answer them. Experience speaks in the text; Innocence responds in the picture. Thus Innocence and Experience continue to be in dialogue, and although the poem is filled with challenging questions about what a creator might be like, it is also an eloquent celebration of creativity and life.

The Chimney Sweeper in Songs of Innocence hinted strongly at social protest, both against the exploitation of small children and against the religious ideology that teaches them to accept their lot. A poem in Songs of Experience is also entitled The Chimney Sweeper, and here the political issues are explicit.

A little black thing among the snow,

Crying “weep, weep,” in notes of woe!

Where are thy father and mother, say?

“They are both gone up to the church to pray.

Because I was happy upon the heath,

And smiled among the winter’s snow,

They clothed me in the clothes of death,

And taught me to sing the notes of woe.

And because I am happy and dance and sing,

They think they have done me no injury,

And are gone to praise God and his priest and king

Who make up a heaven of our misery.”24

The picture (figure 20) presents what for Blake is an unusually three-dimensional, naturalistic scene. The boy, carrying his bag of soot on his back and a wire brush (not easy to see in this copy) in his right hand, looks anxiously up into the pelting snow as he passes houses that are closed against him. He believes that he has been forced to suffer simply “because I was happy upon the heath,” and his blackened garments are indeed clothes of death.

One might suppose that churches in Blake’s day would have seen it as their mission to relieve such suffering, but far from it—they taught that child labor of every kind was a moral obligation. Chimney sweepers, owing to their filthy appearance, were forbidden even to enter a church. If they did try to go in, a reformer said, “They were driven out by the beadle with this taunt, ‘What have chimney sweepers to do in a church?’” Even when churches promoted charity, Blake saw it as hypocritical evasion of responsibility for the injustice that makes charity necessary. The Divine Image in Songs of Innocence declares optimistically:

20. The Chimney Sweeper, Songs of Experience, copy L, plate 41

Pity, a human face,

And love, the human form divine,

And peace, the human dress.

In Experience the corresponding poem, The Human Abstract, is bitterly disillusioned.

Pity would be no more

If we did not make somebody poor,

And mercy no more could be

If all were as happy as we.

It may be worth mentioning that “poor” still rhymes with “more” in the speech of many British people, as it does in Mark Twain—“drot your pore broken heart.”25

Besides The Tyger, the other masterpiece in Songs of Experience is an overwhelming indictment of social injustice. It is entitled simply London.

I wander through each chartered street,

Near where the chartered Thames does flow,

And mark in every face I meet

Marks of weakness, marks of woe.

In every cry of every man,

In every infant’s cry of fear,

In every voice, in every ban,

The mind-forged manacles I hear.

How the chimney sweeper’s cry

Every blackening church appalls,

And the hapless soldier’s sigh

Runs in blood down palace walls.

But most through midnight streets I hear

How the youthful harlot’s curse

Blasts the newborn infant’s tear

And blights with plagues the marriage hearse.26

Blake was a lifelong Londoner. As he imagines wandering through his native city—there is nothing to suggest that the poem’s speaker is different from himself—he is assaulted on every side by sights and sounds of human suffering. Men and children cry aloud (“bans” are curses); chimney sweeps call, “Sweep! Sweep!” in search of work. Indeed, sounds are heard so intensely that they can become sights, in the synesthesia with which Blake seems to have perceived the world. The sighs of soldiers drip like blood on the palace that orders them abroad to die for the British Empire. The cries of chimney sweeps are likewise made visible, in the soot that covers churches like a funeral pall (there may also be a suggestion that the churches should grow pale with horror or shame). James Joyce put it well: “Looking at St. Paul’s cathedral, Blake heard with the ear of the soul the cry of the little chimney sweep. Looking at Buckingham Palace, he sees with the eye of the mind the sigh of the hapless soldier running down the palace wall.”27 It is probably no accident that the initial letters of the third stanza of London spell out the word hear, just as the “newborn infant’s tear” near the end of the poem echoes “every infant’s cry of fear” near the beginning.

Like The Tyger, London has an urgent, driving rhythm. The underlying meter is iambic, but so passionately indignant that it often surges into a trochaic drumbeat:

Hów the yóuthful hárlot’s cúrse

Blásts the néwborn ínfant’s téar. . . .

The accusation is repeated with hypnotic intensity: “in every—in every—in every—in every—in every.” And in the intensity of visionary perception, verbs can become nouns: “Mark in every face I meet / Marks of weakness, marks of woe.” Blake is thinking of passages in the Bible such as the Lord’s command to Ezekiel: “Go through the midst of the city, through the midst of Jerusalem, and set a mark upon the foreheads of the men that sigh and that cry for all the abominations that be done in the midst thereof.”28

The streets are “chartered” because charters played an important role in an intense political debate at the time. London radicals, with whom Blake identified, hoped that a revolution like the one in France could establish liberty, equality, and fraternity. Conservatives, Edmund Burke for example, countered that the English people had more than enough liberty already, guaranteed by legal charters that went all the way back to the Great Charter, the thirteenth-century Magna Carta. But the radicals, such as Thomas Paine, saw this legal system as narrowly restrictive, prohibiting whatever it did not specifically permit. In Blake’s London the very streets are legalistically defined, and even the flowing river is confined between man-made walls.

London is a political protest in a profoundly moral sense, not in a programmatic way. Orwell said, “There is more understanding of the nature of capitalist society in a poem like ‘I wander through each chartered street’ than in three-quarters of socialist literature.” Michael Ferber remarks that near Westminster Bridge today, Blake’s London can be seen chiseled into the stone pavement. Across the river are the Houses of Parliament and the Ministry of Defense, twin strongholds of the very power structure that the poem was written to expose.29

The picture for London (figure 21) complements the text. An aged man on a crutch is being led by a small boy, passing a door closed tight against them. It is evidently winter, since another boy is warming his hands at a fire in the street. The old man may well be blind, as he is when a similar image is invoked in the late poem Jerusalem:

I see London blind and age-bent begging through the streets

Of Babylon, led by a child. His tears run down his beard. . . .

The corner of Broad Street weeps; Poland Street languishes

To Great Queen Street and Lincoln’s Inn, all is distress and woe.30

In his later poems Blake imagined an ideal London as Jerusalem, and the actual London as Babylon. He was born in the family shop in Broad Street, Poland Street was right around the corner, and Great Queen Street is where he spent his seven years’ apprenticeship to James Basire. Close by is Lincoln’s Inn where lawyers were and are trained. In a number of copies of the Songs, the undulating border at the foot of the page in London resembles an earthworm, emblem of mortality; in the copy reproduced here it is a hissing snake.

21. London, Songs of Experience, copy N, plate 21

All of these victims have internalized a cruel ideology, crystallized in the brilliant expression “the mind-forged manacles.” In an earlier draft Blake called them “German forged links,” with the Hanoverian monarchy in mind (see figure 19, page 82, above), but that was too reductive. A generation later Shelley too spoke of fetters that bite “with poisonous rust into the soul,” but he suggested that they might turn out to be “brittle perchance as straw.” Blake’s metaphor is suggestive of manacles made of iron or steel, not straw, and in later poems he often acknowledged how hard it would be to shed them: “He could not take their fetters off for they grew from the soul.” The South African martyr Steve Biko said memorably, “The most potent weapon of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”31

Finally, it is in “midnight streets” that the most harrowing sound is heard. The plight of the youthful harlot forms the culmination of this amazing social indictment, for it gathers together all of the themes of the poem. In Jerusalem Blake speaks of “a religion of chastity, forming a commerce to sell loves / With moral law.” Marriages were regularly arranged between families for financial considerations, wives were encouraged to be chastely asexual, and divorce was virtually unobtainable. So a subculture of prostitution, officially condemned but in practice condoned, grew up for dissatisfied men; women’s needs were not considered. In Jerusalem Blake poses a telling question:

What is a wife and what is a harlot? what is a church? and what

Is a theatre? are they two and not one? can they exist separate?

Are not religion and politics the same thing?

Conventional marriage was thus institutionalized prostitution, and conventional religion was a theatrical performance for a passive audience. Blake would have heard the voice of Satan in T. S. Eliot’s remark, “The only dramatic satisfaction that I find now is in a High Mass well performed.”32 Religion and politics are the same thing because the Church of England is a tool of the repressive state. For Blake the mission of religion should be to inspire change in the world we live in right now, not to preach resignation while awaiting the hereafter.

The most startling thing in the poem is its very last word. In the opinion of the poet and critic John Holloway, “It gives to London the most powerful closing line of any poem known to me in any language.” “Marriage bed” would be the expected idea: the husband contracts a venereal disease from the harlot and then transmits it to his wife, who in turn infects their child (symptoms of gonorrhea, potentially fatal, could show up in a newborn’s tears). In that sense the carriage that bears them away from their wedding is really a hearse in disguise. But society is diseased at a more profound level than just the literal infections that a prostitute might pass on. As with the mind-forged manacles, the implications are all-embracing. “Blake is talking about every marriage,” Bloom says, “and he means literally that each rides in a hearse”—a kind of living death.33

According to a trenchant Proverb of Hell, “Prisons are built with stones of law, brothels with bricks of religion.”34 The distinction is thought-provoking. Stone is a natural substance, hard and durable, shaped with effort and skill into building blocks. Blake unquestionably believed that the criminal justice system in England was corrupt and unjust, but he would not have denied that societies do need laws. Bricks are not stones but mock-stones, soft clay held together with straw and cast in identical molds. And it is religion that builds brothels with them, for the policing of sex by religion is what creates the incentive for brothels to exist.

In the notebook poem known as Auguries of Innocence, we hear the harlot’s cry again, together with the rhyme on “curse” and “hearse.”

The whore and gambler by the state

Licensed build that nation’s fate;

The harlot’s cry from street to street

Shall weave old England’s winding sheet.

The winners shout, the losers curse,

Dance before dead England’s hearse.

Every night and every morn

Some to misery are born;

Every morn and every night

Some are born to sweet delight.

Some are born to sweet delight,

Some are born to endless night.

Quoted by themselves, as they often are, “sweet delight” and “endless night” may seem to acknowledge inevitable human differences, but they are not inevitable at all. The key insight is in the phrase “by the state licensed.” Without it, David Punter observes, “the extract would be mere lamentation; with it, it becomes already a diagnosis.” In London, in just sixteen lines, Blake manages to indict the church, the law, the monarchy, property, and marriage. In marriage, as he sees it, nearly all of the others are combined—maybe even all of them, if one thinks of monarchy as the symbolic embodiment of patriarchy.35

It might seem that London would serve as an appropriate culmination to Songs of Experience, and it does usually appear near the end, but not as the final poem. Just as in Songs of Innocence, Blake varied the sequence of poems from one copy to another. In copy N, the one reproduced here, London is fifth from the end, followed by The Little Vagabond, Holy Thursday, Nurse’s Song, and finally a rather mild poem called The Schoolboy. The Tyger, in the two copies reproduced here, is ninth from the end in copy F and thirteenth in copy Z.

In part because his poems were issued in such limited editions, but also because they are undeniably strange, Blake was virtually unknown as a poet during his lifetime. The few people who bought his illuminated books paid little attention to the texts. Even as an artist he was marginalized, known for little else besides the illustrations to Night Thoughts and The Grave. In his annotations to Reynolds he wrote bitterly, “Fuseli almost hid himself—I am hid.”36 He first wrote, “I was hid,” and then changed “was” to “am.” Henry Fuseli was a mentor and friend, more successful as an artist than Blake, but likewise regarded as eccentric and outside the mainstream.

A few of the early lyrics did find their way into print, for example, the Innocence version of The Chimney Sweeper in a reformist treatise entitled The Chimney Sweeper’s Friend and Climbing Boy’s Album. A reviewer commented, “We know not how to characterize the song given from Blake’s Songs of Innocence. It is wild and strange, like the singing of a ‘maid in Bedlam in the spring;’ but it is the madness of genius.”37 That this perfectly straightforward poem could be called mad suggests just how conventional most readers’ tastes were.

A friend of Blake’s named Benjamin Heath Malkin included a number of the poems, including The Tyger, in a little volume in 1806, and reviewers were even more dismissive. One said condescendingly that the poems were “not devoid of merit,” another that “the poetry of Mr. Blake does not rise above mediocrity.” Shortly after his death someone who knew him well had this to say: “The poetry of these songs is wild, irregular, and highly mystical, but of not great degree of elegance or excellence, and their prevailing feature is a tone of complaint of the misery of man-kind.”38 “Complaint” is a feeble description of Blake’s searing exposure of cruelty, hypocrisy, and exploitation.

Through their mutual friend Henry Crabb Robinson, two great poets, Words-worth and Coleridge, did hear of Blake near the end of his life. Coleridge actually paid him a visit, and Robinson reported that Coleridge “talks finely about him,” though without mentioning what he said. Wordsworth responded favorably to the Songs; he and his sister Dorothy copied out several of them, including The Tyger. But according to Robinson their admiration was qualified. “There is no doubt that this man is mad,” he remembered Wordsworth saying, “but there is something in this madness which I enjoy more than the sense of Walter Scott or Lord Byron.” Coleridge too borrowed Robinson’s copy of the Songs and used a system of markings to indicate the ones he liked best and least, putting Infant Joy at the top. He thought The Sick Rose was good and The Tyger still better, but he ranked The Chimney Sweeper (probably the Experience version) and The Blossom at the very bottom.39

It was a long time before even Wordsworth and Coleridge attained the prestige they now enjoy. When Samuel Johnson’s friend Charles Burney reviewed their breakthrough volume, Lyrical Ballads, he found the poems entertaining but concluded, “We cannot regard them as poetry, of a class to be cultivated at the expense of a higher species of versification.” During that era the most admired poets were Sir Walter Scott, Lord Byron, Robert Southey, Samuel Rogers, and Thomas Moore.40

An eloquent lament in The Four Zoas, begun in the late 1790s, captures all too convincingly the story of Blake’s career:

What is the price of experience? do men buy it for a song,

Or wisdom for a dance in the street? No it is bought with the price

Of all that a man hath, his house his wife his children.

Wisdom is sold in the desolate market where none come to buy

And in the withered fields where the farmer ploughs for bread in vain.41