DURING the early 1790s, inspired by the French Revolution, an organized campaign developed for British political reform. Its focus was on extending the franchise so that more men could vote (not women, of course) and on restructuring parliamentary districts so that the rapidly growing industrial cities would have proper representation. There was also a call to abolish so-called pocket boroughs, in which local magnates would choose members of parliament to suit themselves, as well as rotten boroughs, seats established in the Middle Ages but now with few inhabitants, and in some scandalous instances none whatsoever.

These were important goals, and it took forty years to achieve them if only partially, in the Reform Bill of 1832. Still, the reformers were attempting to work within the political system, not to overthrow it. A small number of radicals saw this program as pitifully inadequate and hoped instead to ignite a vast remaking of the entire social order. Historians have tried hard to identify these people, but that is far from easy, since they were compelled to operate in secrecy. What is clear is that they shared many ideas with the revolutionaries of the 1640s who had executed King Charles I and who proudly appropriated a biblical description of the early Christians as “these that have turned the world upside down.” Those seventeenth-century radicals were known as antinomians, meaning “against the law,” from the Greek nomos. Detesting institutional religion, they believed that the Law of the Old Testament had been abolished, and they anticipated that Puritan victory would ignite a revolution far more profound than mere political change. Jerusalem was to be created anew and an age of brotherhood achieved, as had long been prophesied under the name of the Everlasting Gospel, a phrase from the Book of Revelation.1 One of Blake’s notebook poems is The Everlasting Gospel.

After the Puritans gained power in the 1650s, however, they turned conservative, and made it clear that their radical fringe was no longer welcome. As it turned out, their own rule was short-lived, and the English people welcomed back King Charles II in the Restoration of 1660. Thereafter the antinomians were fiercely persecuted and driven underground, all but invisible until they began to surface again in Blake’s time, a century and a half later. They were never organized and never had a collective program, but the most extreme among them still hoped to get rid of the monarchy, and even to abolish class distinctions altogether.

What contacts Blake may have had with the radical fringe of his day is unknown. The eminent historian E. P. Thompson was convinced that he must have been connected with a tiny splinter group known as Muggletonians, which had a few dozen members at most, but he was never a joiner, and anyway the Muggletonian writings are conventional and obvious by comparison with his.2

Whatever Blake’s personal connection with the radical underground may have been, he certainly sympathized with many of its ideas. It is less illuminating to associate him, as is sometimes done, with self-styled prophets such as Richard Brothers, who proclaimed himself Prince of the Hebrews and was institutionalized for insanity. Blake never claimed to be specially appointed, and he stated explicitly that he was not a prophet in any literal sense. “Prophets in the modern sense of the word,” he wrote, “have never existed. . . . Every honest man is a prophet; he utters his opinion both of private and public matters. Thus, if you go on so, the result is so. He never says such a thing shall happen, let you do what you will. A prophet is a seer, not an arbitrary dictator.” At another time Blake quoted Moses: “Would to God that all the Lord’s people were prophets!”3

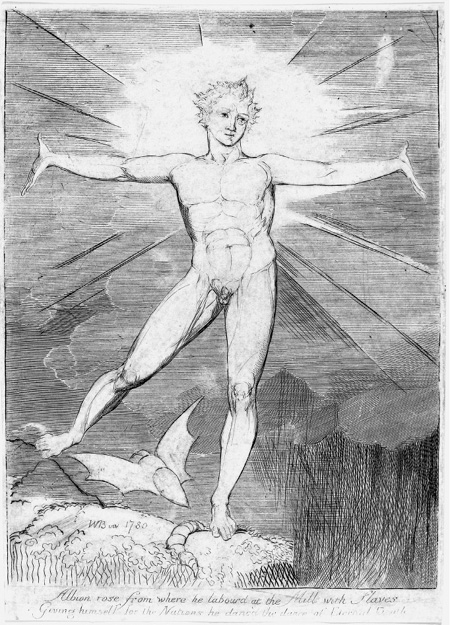

A magnificent color print known as Albion Rose (color plate 11) epitomizes Blake’s vision of national rebirth. The print exists in several versions made over a period of years, and its meaning probably changed for him during that time. The copy reproduced here, now in the Huntington Library in Pasadena, is the second impression from a printing that was done in 1795 or 1796 (the first impression is in the British Museum). Since paint was not reapplied after each printing, it inevitably got thinner after the first copy was made. In this one, lines show through that reveal that the design was engraved on copper before colors were applied.4

At first the print was untitled, and Gilchrist, just guessing, called it Glad Day, a name it continued to go by for a long time. But Blake’s own title is indicated by an inscription he added to a final copy around 1804:

Albion rose from where he laboured at the mill with slaves

Giving himself for the nations he danced the dance of eternal death

“Death” for Blake means what we normally call life—the living death of isolated selfhood in a mechanical universe. In an early work, There Is No Natural Religion, he likens that existence to the endless grinding of a mill: “The same dull round even of a universe would soon become a mill with complicated wheels.”5

Albion was a traditional poetic name for England, and in Blake’s early works it refers simply to the land, as it does in Spenser and Milton. But in his poems in the 1800s, when this inscription was added, Albion becomes a full personification, a giant form in whom all the people of England are embodied. “At the mill with slaves” alludes to Milton’s blind Samson, forced to labor “eyeless in Gaza, at the mill with slaves.” Like Samson, Albion triumphs through death, but in Blake’s symbolism that self-sacrifice is actually an ascent into life, “giving himself for the nations.” He must have been thinking also of a famous passage in Milton’s Areopagitica: “Me-thinks I see in my mind a noble and puissant nation rousing herself like a strong man after sleep, and shaking her invincible locks.”6

On the final state of the print Blake inscribed “W.B. inv 1780.” “Inv” was the printmakers’ term for “invenit,” referring to the “invention” of the design. But it is not likely that he actually engraved it at that early date, for in that case he would have added “sculp” for “sculpsit,” the sculptural process of incising lines into the plate. What he probably meant is that he first conceived the design, perhaps in the form of a sketch, in 1780, even though he didn’t produce the print until fifteen years later.7

The 1780 date suggests at least two implications. That was the year when Blake completed his apprenticeship and was free at last to develop his own style. And it was also when he found himself unexpectedly swept along in what became known as the Gordon Riots. An enraged mob, inflamed by anti-Catholic feeling but also by general grievances, surged through the streets and broke open Newgate Prison, allowing hundreds of prisoners to escape. After a week of anarchy the army was called out and opened fire indiscriminately, killing nearly three hundred rioters. Albion Rose may well have been originally conceived as a symbol of popular insurrection, and when Blake later added the reference to the dance of death he may have been thinking of Edmund Burke’s contemptuous phrase, “the death dance of democratic revolution,” which implied that calls for reform were really just a cover for mob anarchy.8

With a radiant sunrise behind him, Albion’s pose is expansive. As W. J. T. Mitchell says, the picture gives an impression of “a human body glowing with vitality, radiating an aura of sensuous light and heat—the image of Albion dancing in liberated ecstasy.” Mitchell notes also that while the posture recalls Renaissance diagrams of ideal human proportions, they usually center on the navel, whereas this one is centered on the genitals. There may even be a personal reference in Albion’s curly golden hair. Frederick Tatham said that in Blake’s youth “his hair was of a yellow brown, and curled with the utmost crispness and luxuriance. His locks, instead of falling down, stood up like a curling flame, and looked at a distance like radiations.”9

In the late, uncolored 1804 print of Albion Rose (figure 22) two creatures have been added. In the original version Albion’s feet had rested on stone covered with mottled vegetation. In this revised print the vegetation is gone, the right foot is in the air, and the left foot tramples on what may be an earthworm, or else the larval form of the moth taking wing above it. As already noted, earthworms are a recurring symbol of the cycle of mortality, and moths or butterflies of the soul’s liberation from it. But then, why does this weird moth have wings like a bat? Bats are negative symbols for Blake. One possible interpretation is that Albion is indeed liberated and that the bat-moth is an oppressive fiend from which he has joyfully escaped. But it may also be that these additions reflect disillusionment with revolution. Just as the French Revolution, which Blake had eagerly hailed in 1789, degenerated into the horrific Terror, so in the perspective of 1804 Albion’s dance may be a true dance of death after all.10

22. Albion Rose, second state

Blake’s most overtly antinomian work is The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, probably published in 1793. It seems to have begun as a limited satire on the teachings of Emanuel Swedenborg, who struck Blake as a conventional church founder only pretending to be an inspired visionary.11 Soon, however, it grew into a wide-ranging challenge to orthodox morality, in an extraordinary medley of biblical imitation, prose satire, poetry, and homemade proverbs.

In celebrating what he calls Hell, Blake has in mind something very different from the usual connotations of that word. The fundamental idea in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is that theologians and preachers have wrongly stigmatized energy as diabolical, even though it is absolutely essential to existence. They claim that “good is the passive that obeys reason; evil is the active springing from energy.”12 Blake’s counterclaim is that Heaven and Hell must interact as vital contraries, like partners in a marriage who are different yet joined. Both are equally important, though in his enthusiastic polemic Hell gets the better of the argument.

The title page (color plate 12) magnificently embodies these ideas. Gilchrist may not have understood it fully, but he described it well: “The ever-fluctuating colour, the spectral pigmies rolling, flying, leaping among the letters; the ripe bloom of quiet corners, the living light and bursts of flame, the spires and tongues of fire vibrating with the full prism, make the page seem to move and quiver within its boundaries.”13

In a rather pallid scene at the top, a courting couple strolls demurely and a woman reclines while her suitor reads to her (or perhaps plays a musical instrument). The trees above them are drooping and leafless. But from below, energy surges powerfully up, and a pair of naked figures embrace. An antinomian devil rises from the flames, and an orthodox angel rests upon a cloud; their union is repeated above in the small soaring couples. But the torsion in the embrace is striking: although they are locked in a kiss, their bodies extend and twist in opposing directions. Marriage is not identity, and for that matter, gender is not necessarily its basis. Both figures are female, as is clearly apparent in an uncolored copy, although the one on the left—the devil, presumably—is more voluptuous.14 Over the years Blake’s ideal figures would become increasingly androgynous.

A recurring theme of Blake’s work is that his symbols express what goes on in our minds, and it is possible to see in this title page design the shape of a human head. The trees outline its hairy scalp, the courting couples are its eyes, and the circle around the word “and” is its mouth. Our world as we normally perceive it lies above the line that runs, as it were, from ear to ear. Beneath burns the energy that makes life possible. And both worlds, Heaven and Hell, exist within human consciousness.15

Flaming energy is one aspect of vital existence, but there are tranquil aspects too. In another image (color plate 13) a naked young man, with genitals frankly exposed, looks up hopefully into the sky. The skull under his knee is a reminder that revolution abolishes bondage to dead ancestors. Horrified by the French Revolution, Burke declared that society is a contract that must not be altered: “As the ends of such a partnership cannot be obtained in many generations, it becomes a partnership not only between those who are living, but between those who are living, those who are dead, and those who are to be born.” Thomas Paine retorted, “Mr. Burke is contending for the authority of the dead over the rights and freedom of the living. . . . As government is for the living and not for the dead, it is the living only that has any right in it.” Blake put it crisply in one of the Proverbs of Hell: “Drive your cart and your plow over the bones of the dead.”16

Remarkably, in every copy of this plate except the one reproduced here, there are no pyramids. They were never in the etched design but were added with water-color on this particular copy. It must have struck Blake as appropriate to introduce a symbol that he often used in his poems, the pyramids of Egypt, recalling the bondage from which the Israelites escaped. In his last poem, Jerusalem, London laborers don’t just make bricks, they become bricks:

Here they take up

The articulations of a man’s soul, and laughing throw it down

Into the frame, then knock it out upon the plank, and souls are baked

In bricks to build the pyramids of Heber and Terah.

(Terah was the father of Abraham, and Heber an earlier patriarch.)17

A memorable section of The Marriage of Heaven and Hell is entitled “Proverbs of Hell,” which are really anti-proverbs. Ordinary proverbs convey conventional truisms, even when they sometimes contradict each other, as in “Absence makes the heart grow fonder” but also “Out of sight, out of mind.” Blake’s aphorisms are anything but conventional: “Exuberance is beauty”; “The cistern contains, the fountain overflows”; “The tygers of wrath are wiser than the horses of instruction”; “He who desires but acts not, breeds pestilence”; “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.” At times these anti-proverbs seem deliberately intended to shock: “Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires.”18 Blake can’t mean that every possible desire should be acted on, and still less that babies should be murdered, but rather that an unacted desire is like an infanticide. Just as we nurse a grudge, so we may nurse a desire that we are unable or too cowardly to gratify. Yet if that is indeed the meaning, it is not an immediately obvious one. The point of Blake’s proverbs is not to restate what we already know but to make us think.

Since they are so very open-ended, these proverbs are easily detachable from their context. “What is now proved was once only imagined,” says one of the Proverbs of Hell, referring presumably to spiritual insight. But some years ago I encountered it blazoned on the display window of a Paris boutique: what was once only imagined by the designer now dresses the mannequins in the window (figure 23). The library in Donald Trump’s extravagant edifice on Central Park in New York reportedly displays another Proverb of Hell, transformed into a self-congratulatory slogan: “The road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom.”

23. Paris boutique

In 1793, the same year as The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Blake published his most hopeful account of revolution. America: A Prophecy is prophetic in the sense already explained, a commentary on the meaning of events, not a prediction of the future. The illuminated books from this period are known collectively as the Lam-beth Books, after the district south of the Thames where the Blakes were then living. It was amusing that a near neighbor was the archbishop of Canterbury, whose official residence is Lambeth Palace.

The “Preludium” of America introduces a new character, Orc, a name adapted from a Latin word for the infernal regions (it is also the source of an Old English word from which J. R. R. Tolkien named his orcs). Blake’s Orc seems demonic to the established order, for he is the youthful spirit of rebellion, striving to burst his shackles. In America he first appears as a sprawling naked youth fettered to a rock (color plate 14). This late copy, made to appeal to an art collector, is stunningly beautiful. The outline is printed in rich blue, and in applying watercolors great care has been taken to keep the blue sky and yellow leaves from blurring into each other.19 The text is an especially elegant example of Blake’s italic lettering, easily legible but obviously inscribed by hand, and at times it flourishes into life in ways that printed typography never could. In the sixth line, for example, the initial “W” trails a tendril downward, and the “d” of the final word “need” spirals upward.

What exactly are we looking at? Many possibilities have been proposed. The youth resembles Prometheus fettered to his cliff in the Caucasus, and there may also be an allusion to the Crucifixion, since Christ too is a god who suffers on behalf of humankind. The adults in the picture resemble Adam and Eve in traditional depictions of the expulsion from Paradise, but instead of repenting for sin as in the title page of Songs of Innocence and of Experience, they recoil in shock at what they are seeing. Perhaps the young man is a conflated version of their two sons, the martyred Abel and the murderer Cain.20

In the classical myth Prometheus occupies a kind of absolute space, hanging above the world on his rock of agony. In Blake’s picture we are gazing down at the rock, which is really just the surface of the ground, with gnarly humanized roots below. At the bottom a naked man sits huddled and brooding, as if awaiting resurrection, and beneath the text is an earthworm, symbolic of mortality once again. It has six coils because, in a phrase Blake used several times, man is “a worm of sixty winters.”21

In the accompanying text, “red Orc” has reached his fourteenth year, the age of puberty, and yearns to seize “the shadowy daughter of Urthona,” who brings him food and drink. She is not otherwise identified, and for that matter neither is Urthona, though the name may suggest “earth owner.” Perhaps she is the American continent itself.

In the next plate Orc has somehow broken free and is able to gratify his desire.

Silent as despairing love, and strong as jealousy,

The hairy shoulders rend the links; free are the wrists of fire.

Round the terrific loins he seized the panting struggling womb;

It joyed: she put aside her clouds and smiled her first-born smile,

As when a black cloud shows its lightnings to the silent deep.

Soon as she saw the terrible boy then burst the virgin cry:

“I know thee, I have found thee, and I will not let thee go.”

This is commonly seen as a rape, which is undoubtedly right; similar sexual violence occurs in Visions of the Daughters of Albion, which was published in the same year as America. Blake’s ambiguous and often disturbing view of sexuality will be considered later. Here it has to be acknowledged that the violation is apparently welcomed by the “shadowy daughter.” Her womb “joys,” and her speech echoes the Song of Solomon, “I found him whom my soul loveth: I held him, and would not let him go.”22

Perhaps Blake’s meaning is that although revolutions are inevitably violent, Orc’s energy is libidinal, not destructive. Otherwise it would be inexplicable that it is Orc who is given this eloquent speech later on:

For every thing that lives is holy, life delights in life;

Because the soul of sweet delight can never be defiled.

Similarly, the picture that accompanies the lines about Orc’s union with the shadowy daughter (figure 24) is not violent at all. No longer chained down, the young man gazes hopefully into the sky while a grapevine spirals upward from underground roots. This monochrome copy shows Blake’s firm outlines to advantage, and since ten of the copies in the original 1793 printing are uncolored, he may have hoped to sell them cheaply to a wide audience, not just to collectors of art.23

As Blake imagines it, the American Revolution could have been the spark to ignite a universal uprising, in which the French Revolution would be followed by a British revolution yet to come. Though actual events in America are barely mentioned in the poem, we do meet some familiar characters:

Fury! rage! madness! in a wind swept through America

And the red flames of Orc that folded roaring fierce around

The angry shores, and the fierce rushing of th’ inhabitants together.

The citizens of New York close their books and lock their chests;

The mariners of Boston drop their anchors and unlade;

The scribe of Pennsylvania casts his pen upon the earth;

The builder of Virginia throws his hammer down in fear.

Then had America been lost, o’erwhelmed by the Atlantic,

And Earth had lost another portion of the infinite,

But all rush together in the night in wrath and raging fire.

24. America: A Prophecy, copy E, plate 4

The mariners are the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Franklin is the scribe of Pennsylvania, and Jefferson is the builder of Virginia. In their own minds those rebels were rejecting the authority of George III but keeping the social order pretty much unchanged. In Blake’s vision it is the people united who “rush together,” much to the alarm of their self-styled leaders, who drop their pen and hammer and lock up their valuables. It didn’t actually happen like that, as he knew perfectly well, but from a prophetic point of view it should have.24

In another picture (figure 25) Orc appears in a pose very similar to one that we saw in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, genitals displayed without shame and a skull at his side. In colored copies he has curly yellow hair, reminiscent of Albion Rose—and of William Blake. Commentators have noted also the relevance of an ancient Roman statue known as the Barberini Faun, in which a dissolute figure lounges in a suggestive posture, dozing and presumably drunk. There is nothing indecent about Blake’s figure, which might be taken to illustrate a Proverb of Hell: “The head sublime, the heart pathos, the genitals beauty, the hands and feet proportion.” Christopher Hobson comments, “Though there is nothing homosexual as such about this design, it is an image of intense, and intensely vulnerable, male beauty.”25

The text in this plate celebrates liberation, in some of the most eloquent lines that Blake ever wrote:

The morning comes, the night decays, the watchmen leave their stations;

The grave is burst, the spices shed, the linen wrapped up;

The bones of death, the covering clay, the sinews shrunk and dried

Reviving shake, inspiring move, breathing! awakening!

Spring like redeemed captives when their bonds and bars are burst.

Let the slave grinding at the mill run out into the field;

Let him look up into the heavens and laugh in the bright air;

Let the enchained soul shut up in darkness and in sighing,

Whose face has never seen a smile in thirty weary years,

Rise and look out, his chains are loose, his dungeon doors are open,

And let his wife and children return from the oppressor’s scourge.

They look behind at every step and believe it is a dream,

Singing: “The sun has left his blackness, and has found a fresher morning,

And the fair moon rejoices in the clear and cloudless night,

For empire is no more, and now the lion and wolf shall cease.”

25. America: A Prophecy, copy E, plate 8

These lines are full of biblical echoes. The slave at the mill and the watchmen come from the Gospel of Matthew, and the linen clothes from Christ’s empty tomb in the Gospel of John. Ezekiel saw the dry bones revive: “I prophesied as I was commanded: and as I prophesied, there was a noise, and behold a shaking, and the bones came together . . . and the breath came into them, and they lived, and stood up upon their feet, an exceeding great army.”26

The language is dynamic—shaking, springing, running—but the seated figure is at rest, pondering the future now that the dungeons have been broken open. The plants and small creatures at the bottom of the picture may be allegorical references of some kind, but if so they are obscure. At any rate they seem to be at home in a healthy natural world, very like the creatures in the picture for The Clod and the Pebble.27

Revolution is fed by energy, and in another picture (figure 26) Orc is buoyed up by flames that even invade the text. William Michael Rossetti, Dante Gabriel’s brother, called Blake “the supreme painter of fire,” and Blake himself coined the memorable phrase “fire delights in its form.” In another work from this period he speaks of the “thick-flaming, thought-creating fires of Orc” (he knew Shakespeare well and may have been recalling Lear’s “sulfurous and thought-executing fires”). As Mitchell says, in this picture the flames “are to be seen as inside him, as an externalization or projection of his consciousness.”28

It could also be said that Orc embodies an aspect of our own consciousness. But he is not the only aspect, and in this picture his expression is uneasy, for he has a mighty antagonist who is equally fundamental to consciousness. That character Blake calls Urizen, a white-bearded patriarch who is associated with God the Father, and with patriarchs of every kind from kings and bishops down to ordinary fathers.

26. America: A Prophecy, copy E, plate 12

In a visual parallel to the image of Orc in flames, Urizen appears in a similar pose (figure 27), although balanced on the opposite foot, and not naked but robed in a heavy, full-length gown. In the text immediately below,

The terror answered: “I am Orc, wreathed round the accursèd tree.

The times are ended; shadows pass, the morning gins to break;

The fiery joy, that Urizen perverted to ten commands,

What night he led the starry hosts through the wide wilderness:

That stony law I stamp to dust, and scatter religion abroad

To the four winds as a torn book, and none shall gather the leaves.”29

The accursed tree is the prohibited tree of knowledge, at whose foot the biblical serpent tempted Eve. The implication is that to the forces of reaction, Orc does appear a diabolical serpent, twining around the forbidden tree. Like the activist Satan in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, his mission is to smash the repressive law that Moses brought down from Mount Sinai on tablets of stone.

Urizen is sitting on heavy clouds, embracing them like boulders, while he gazes gloomily down on the world below. His expression is no more hopeful than Orc’s in the companion picture, but everything about Urizen expresses heaviness, whereas Orc rises upward in his flames, spreading his fingers to catch the updraft. Urizen’s clouds are modeled with elaborate cross-hatching of the kind used in commercial copy engraving, and it has been argued that Blake thought of this laborious technique as a visual sign of repressive control.30

Northrop Frye once described the struggle of Urizen and Orc as an “Orc cycle,” in which every revolution degenerates into repression and every Orc becomes a Urizen. Frye was so persuasive that generations of critics adopted his idea, but in fact there is no basis for it in the poems themselves. Blake understood very well that revolutions can turn cruel, as was happening in France, but Orc and Urizen are not two names for the same thing. An older commentator, Milton Percival, described Orc more accurately as “a deathless phenomenon, the spirit of revolution that arises when energy is repressed.”31

27. America: A Prophecy, copy E, plate 10

Even in this optimistic early poem, Blake was thinking about revolution from multiple points of view, and his creative deployment of symbols was well suited to expressing that complexity. In conventional art, iconic symbols usually have a stable, consistent meaning; thus a cross signifies Christianity, a pair of scales justice. But Blake’s symbols are dynamic, not iconic. We learn what they mean by observing what they do, and their actions change according to context. Another way of saying this is that they play active roles in an ever-evolving myth, and since the myth is being invented by Blake himself, we can’t rely on traditional associations, even when he borrows materials from the Bible or Milton or the Bhagavad Gita.32

The imagery of the serpent is an excellent example of the range of implications in a single dynamic Blakean symbol. The sequel to America is a poem called Europe: A Prophecy, with a startling title page (color plate 15). This spectacular reptile is usually thought to symbolize Orc’s rebellious energy, as perceived by the forces of repression, and perhaps recalling the snake with three coils in the American “Don’t Tread on Me” flag. Erdman sees the image as entirely positive, “embodying energy, desire, phallic power, the fiery tongue,” but other interpreters suspect a negative message. Morton Paley asks, “Does the grinning, coiled Orc serpent of the title page suggest that although Energy promises apocalyptic freedom, it actually betrays man to the cycle of history?”33

During the course of Europe, the serpent does in fact become a symbol of nature-worshipping repression. An “ancient temple serpent-formed” is constructed of huge stones in a winding pattern, like the one at Avebury that in Blake’s time was attributed to Druid priests (see figure 38, page 193, below).

Thought changed the infinite to a serpent; that which pitieth

To a devouring flame; and man fled from its face and hid

In forests of night. Then all the eternal forests were divided

Into earths rolling in circles of space, that like an ocean rushed

And overwhelmed all except this finite wall of flesh.

Then was the serpent temple formed, image of infinite

Shut up in finite revolutions, and man became an angel;

Heaven a mighty circle turning; God a tyrant crowned.34

Planets revolve endlessly in the solar system, which is mimicked by the serpent temple in which priests propitiate their god with human sacrifice. “Forests of night” recalls the ambiguous creator of The Tyger.

In America, however, there is also an auspicious image of a serpent, on whose back three children ride at their ease (figure 28). The oldest holds the reins lightly, while the middle child reaches back to help the youngest. The serpentine form is repeated higher up in the neck of a soaring swan whose reins are held by a muscular young man. Above his head appear the words “Boston’s Angel”—he might be an aerial version of Paul Revere. Both swan and serpent can be seen as phallic, and Blake knew of a sculpture from Herculaneum that showed a child riding on an enormous penis.35 Here serpent symbolism is clearly positive, though no one has satisfactorily explained why images of night are glimpsed behind the clouds—a crescent moon, and the constellation of the Pleiades.

There are other animals in America besides serpents. One lovely picture (color plate 16) presents a total contrast to the furious text on the same plate, in which a wrathful Albion’s Angel, the “spiritual form” of George III, denounces Orc as “serpent-formed . . . blasphemous demon, Antichrist, hater of dignities.” Under a delicate tree on which birds of paradise perch, a naked young woman lies asleep on the ground, and a curly-headed young man rests on the woolly back of a sleeping ram. Very likely they have been making love. In this late, colored copy a sunrise suffuses the sky. It is a vision of Innocence, more explicitly sexualized than in Songs of Innocence, that invokes an alternative reality to rebellion and repression. It also fulfills the declaration that concludes the previous plate, “For empire is now no more, and now the lion and wolf shall cease.”36

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell sexuality was positive, and in the heyday of the 1960s counterculture Blake was often invoked to that effect. But he was always aware that sex can be a means of exerting control, and at times he was tormented by it. It is probably no accident that most of the naked bodies in Blake’s pictures are un-erotic, and at times positively repellent. We know that his hero was Michelangelo, about whom an art historian asks, “Why are his Madonnas so unmaternal? Why are his figures of superhuman scale and size?”37

Here, in Europe, two of the most attractive bodies Blake ever depicted (color plate 17) turn out to have highly negative implications. “No nude, however abstract,” Kenneth Clark says, “should fail to arouse in the spectator some vestige of erotic feeling, even though it be only the faintest shadow—and if it does not do so, it is bad art and false morals.” Insofar as that is true, Blake makes ironic use of it, for what his text describes is “Albion’s Angel smitten with his own plagues,” in consequence of England’s counterrevolutionary war against France. These two shapely figures are in fact fairies scattering blight upon the crops through swirling trumpets. In a kind of visual pun, the trumpets emit blasts of sound just as mildew blasts grain. So England is being punished by the very plague it has brought into being, and the context completely undermines the erotic attractiveness of the picture.38

28. America: A Prophecy, copy E, plate 13

A sign of Blake’s disillusionment with revolution is that in one of two copies of America that he printed in 1795, four lines were added on the plate that shows the young man clambering out of the ground:

The stern Bard ceased, ashamed of his own song; enraged he swung

His harp aloft sounding, then dashed its shining frame against

A ruined pillar in glitt’ring fragments; silent he turned away,

And wandered down the vales of Kent in sick and drear lamentings.

Smashing a harp was a traditional bardic refusal to perform in slavery.39

As early as 1792 a royal proclamation promised “to prosecute with severity all persons guilty of writing and publishing seditious pamphlets tending to alienate the affections of his Majesty’s subjects, and to disturb the peace, order, and tranquility of the State, as well as to prohibit all illegal meetings.” Prosecutions and imprisonment followed, and it must have been especially concerning for Blake that the Stationers’ Company published a “determined resolution utterly to discountenance and discourage all seditious and inflammatory productions whatever.” That resolution was signed by numerous publishers on whom he depended for income, as well as by his former master Basire.40

Whatever contribution Blake may once have thought of making to the anticipated revolution, by the mid-1790s he was retreating from any active political stance, and the few copies of his early illuminated books that still exist today were all sold or given to trusted friends. Starting with The Book of Urizen, which will be considered later, he turned instead to a critical dialogue with the Bible and then stopped creating illuminated books altogether for over a decade. He genuinely believed that if the authorities should become aware of his writings, his life might be in danger. He wrote in his notebook, “I say I shan’t live five years, and if I live one it will be a wonder. June 1793.” He was talking about legal persecution, not physical health. In 1797, annotating a bishop’s attack on Thomas Paine, he declared, “I have been commanded from Hell not to print this; it is what our enemies wish.”41

Besides fearing prosecution, Blake was becoming apolitical in any activist sense, and commentators who insist that he never retreated from political commitment are using the term in a very broad sense. In the more usual sense, he wrote in 1810, “I am really sorry to see my countrymen trouble themselves about politics. If men were wise the most arbitrary princes could not hurt them. If they are not wise the freest government is compelled to be a tyranny. Princes appear to me to be fools; Houses of Commons and Houses of Lords appear to me to be fools. They seem to me to be something else besides human life.”42

Blake lived for sixty-nine years, and Britain was at war during half of that time. It fought in vain to hold on to its American colonies, it fought in vain to suppress the French Revolution, and then it fought with success to bring down the Napoleonic empire. Writing about Blake during World War II, Jacob Bronowski commented that “after the eagles and the magnificence, [the age of Napoleon] remains in the memory as Goya savagely pictured it: twenty-two years without conscience, stamping the men and the treasure of Europe into the dirt.”43

The increasing pessimism of Blake’s later poems has perplexed critics who would like to see him as a forerunner of Marxism, or at least of working-class radicalism. But class solidarity was never part of his thinking, and although he resented many aspects of capitalism, his values were those of an independent artisan. Whatever may have been lost when the dream of revolution faded, as he continued to develop his ideas he wrote no more political poems like America and Europe, and instead explored perennial tensions in human experience in ever-increasing depth. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell he had made a declaration that is often quoted as if it were the key to his thought: “Without contraries is no progression. Attraction and repulsion, reason and energy, love and hate, are necessary to human existence.”44 In Blake’s later writings contraries would continue to play a central role, but we no longer hear of forward-trending “progression.” And whereas Urizen would remain a central figure in his mythic thinking, Orc would dwindle from view, and a whole new cast of symbolic characters would need to be invented.