UNDERLYING Blake’s critique of the psychological, political, and religious assumptions of his time was a conviction that modern ways of thought blind us to the fullness of experience. As a stopgap measure in their retreat from belief, eighteenth-century agnostics were fond of recommending deism (from the Latin deus), also known as natural religion, which claimed that anything worth knowing about the deity could be deduced rationally from the orderly processes of nature. Just as a clock must be the work of a skilled clockmaker, so the solar system must be the product of a clockmaker-god. Such a god, of course, need have no interest whatever in human beings, and Blake thought that an impersonal, detached deity like that was no god at all. But neither was the orthodox Jehovah. The god Blake did acknowledge was the very human Jesus whose benevolent presence pervades Songs of Innocence.

Blake’s attack on natural religion, and the symbolism with which he counters it, are embodied in an unpublished lyric in his notebook, which has no title and no accompanying picture.

Mock on Mock on Voltaire Rousseau

Mock on Mock on! ’tis all in vain!

You throw the sand against the wind

And the wind blows it back again

Reflected in the beams divine

Blown back they blind the mocking eye

But still in Israel’s paths they shine

The atoms of Democritus

And Newton’s particles of light

Are sands upon the Red Sea shore

Where Israel’s tents do shine so bright1

Always sparing with punctuation, Blake used none at all here except for a pair of exclamation points. He evidently wanted each line to carry its own separate weight, not to slot neatly into place in tidy syntax.

Voltaire and Rousseau were leading figures in the Enlightenment, so called because it aspired to shed light on the dark places of superstition and tyranny. After the French Revolution the remains of these two great philosophes were reinterred next to each other in the Pantheon, but in life they had thought of themselves as opposites. The worldly, sophisticated Voltaire was a cynical wit, a rich landowner, and an admirer of philosopher-kings. Rousseau was a loner and hermit, a spokesman for “natural” simplicity, and the theorist of a radically new political system that would embody the “general will” of all citizens. From Blake’s point of view, however, the affinities were deeper than the differences. He saw both Voltaire and Rousseau as believers in natural religion, and his own conviction was that the natural world as understood by modern thinkers was a barrier against truth, not a window into it.

What Blake did approve of in the Enlightenment was its campaign against institutional religion. Voltaire had a favorite slogan, Écrasez l’infâme: “Crush the infamous thing,” meaning the Catholic Church, which controlled French education, imposed orthodox theological doctrine, and rigorously censored publications. He rejected most of orthodox doctrine as moralizing thought control, and so did Blake, who agreed that it was wrong to take the Bible as literally and factually true. “Voltaire was commissioned by God,” he said, “to expose that.”2

In Blake’s view, the thinkers of the Enlightenment performed a necessary act of destruction with their critique of orthodoxy, but they didn’t know how to reconstruct. In an inspired metaphor, he exploits the fact that although grains of sand can look like inert particles, if thrown up into sunlight they sparkle like jewels. The philosophes made that happen when they stirred up the sands of superstition, but because they foolishly faced into the wind, the sharp crystals stung their eyes into spiritual blindness.

There is another way to think about sand, though. Theorists of science in Blake’s day thought that nature is best understood through mathematical laws, which supposedly described the interaction of atoms, far too tiny to be seen. Atoms were not conceived of as force fields, as they would be today; they were more like identical marbles in a bag. The ancient philosopher Democritus had imagined them as unbreakably solid building blocks, and in empiricist philosophy they were held to constitute everything that exists, including ourselves. As for the so-called secondary qualities that we perceive as color and taste and odor, they have no real existence at all. They are merely illusions that our brains construct from the sense data that stream in on us. As summarized by a modern historian of science, “The world that people had thought themselves living in [before empiricism]—a world rich with color and sound, redolent with fragrance, filled with gladness, love and beauty, speaking everywhere of purposive harmony and creative ideals—was now crowded into minute corners of the brains of scattered organic beings. The really important world outside was a world hard, cold, colorless, silent, and dead; a world of quantity, a world of mathematically computable motions in mechanical regularity.”3

Blake understood these implications and utterly despised them. “Deduct from a rose its redness,” he wrote, “from a lily its whiteness, from a diamond its hardness, from a sponge its softness, from an oak its height, from a daisy its lowness, and rectify everything in nature as the philosophers do, and then we shall return to chaos.”4

Isaac Newton was a major culture hero in the eighteenth century, much as Albert Einstein would be in the twentieth. And like Einstein, Newton advanced theories that only specialists could grasp. His masterpiece was Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica—Mathematical Principles of Natural Philosophy. For nonexperts the math was impossibly difficult, but Newton’s other classic, Opticks, was a book that ordinary readers could understand. Using prisms and lenses, he conducted a series of experiments on the properties of light, showing that a prism breaks seemingly white light into all the colors of the spectrum. Alexander Pope wrote a memorable epitaph:

Nature and Nature’s laws lay hid in night;

God said, “Let Newton be!” and all was light.

With similar awe, Blake’s contemporary Wordsworth described a statue at Trinity College, Cambridge, where Newton had once lived and taught:

Newton with his prism and silent face,

The marble index of a mind for ever

Voyaging through strange seas of thought, alone.5

Blake would certainly not have disagreed that raindrops and prisms reveal the colors of the rainbow. What he objected to was Newton’s claim that like everything else, light was composed of minute particles, which he called corpuscles. At the creation of the universe, Newton wrote, God “formed matter in solid, massy, hard, impenetrable, movable particles,” which resemble each other just as much “as the sands on the shore.”6 Whenever we open our eyes, the stream of particles strikes our retinas and triggers signals in the brain. Blake invokes Newton’s “sands on the shore” for a very different purpose: for him they suggest the Sinai Desert—“sands upon the Red Sea shore”—through which the Israelites journeyed from Egyptian captivity to the Promised Land. Newton described the ways in which light always behaves; Blake invokes a great symbolic story, the Exodus from bondage to freedom. The light that illuminates that journey is a spiritual force, not a hailstorm of material particles.

There is also a grain of sand in another of Blake’s notebook poems:

To see a world in a grain of sand

And a heaven in a wild flower,

Hold infinity in the palm of your hand

And eternity in an hour.

One of Blake’s favorite writers was the seventeenth-century German mystic Jacob Boehme, who wrote, “When I take up a stone or clod of earth and look upon it, then I see that which is above and that which is below; yea, I see the whole world therein.” That kind of mysticism is very different from the kind that dismisses the visible world as mere illusion. Far from wanting to escape to a “higher” realm, Blake, like Boehme, sought richer apprehension of this one. “I can look at a knot in a piece of wood,” he once said, “till I am frightened at it.” Perhaps surprisingly, he was friendly with the far better known painter John Constable. Once, leafing through Constable’s sketchbook, Blake commented on a drawing of trees, “Why, this is not drawing, but inspiration.” “I never knew it before,” Constable replied, no doubt with a smile. “I meant it for drawing.” It is the same real world that we inhabit all the time but seen with new freshness, or with what Robert Frost calls “strangeness.”7

Infinity, the empiricists thought, was a meaningless concept, since we are unable to comprehend a universe that goes on forever without end. Likewise eternity was meaningless, since all we can ever actually know is the ticktock of each successive second. Blake would agree that those were hopelessly abstract ways of trying to imagine infinity and eternity, but for him both were immediate and concrete. Infinity is present here and now in the real world we inhabit, not far away in unimaginable endlessness. Eternity, likewise, is present in each moment of lived experience; it is the river of time in which we are continuously immersed. He coined a memorable term for it—“the Eternal Now”—and he would have appreciated Ludwig Wittgenstein’s statement, “If we take eternity to mean not infinite temporal duration but timelessness, then eternal life belongs to those who live in the present.” “Eternity is in love with the productions of time,” Blake wrote in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell; elsewhere he called time “the mercy of Eternity.”8 Perhaps that means that for mortal men and women, the vastness of Eternity would be overwhelming if we were fully conscious of it. Mercifully, we are aware only of the onward flow of time in which we are immersed.

Although Blake criticized Newton’s assumptions as reductive, he nevertheless had a generous admiration for Newton’s genius. The great physicist is the subject of an extraordinary picture (color plate 18), though without knowing that its title is Newton one would be hard put to guess what it shows. Here Newton is very much alone, as in Wordsworth’s lines, but not gazing into the heavens as the statue does. On a lichen-encrusted rock at the bottom of the sea, he sits in a constricted posture, compressed almost into a ball, the very opposite of the wide-flung limbs in pictures such as Albion Rose. Tracing a geometric diagram with a pair of compasses, he stares with intense concentration at a little scroll.

Whereas the Newton of history was a gaunt, ascetic professor, this Newton is a muscular athlete. Hunched over though he is, his powerful body, with clearly articulated muscles, contrasts vividly with the simplified diagram that he believes to be a true picture of reality. Much as Michelangelo would, Blake has thus translated intellectual power into a physical equivalent.9 Newton is shown on the sea floor because Blake adopted from Neoplatonic philosophy the symbolism of water as suffocating materiality. But by implication nothing is stopping him from getting up off his rock and rising to the surface, into the world of sunlight and fresh air. Nor does he show any interest in the intricate and beautiful life-forms that cover his rock. Newton is a mighty genius, but also the prisoner of a reductive intellectual program. Blake’s intention in this picture is not to deny his greatness but to suggest the imaginative bondage that his intellectual system imposed.

It is interesting that when Blake did try to study geometry, he couldn’t see the point of formal proofs as opposed to immediate intuition. Thomas Taylor, whose translations of Plato Blake used, undertook to tutor him. According to someone who knew Taylor, they got as far as the fifth proposition in Euclid, “which proves that any two angles at the base of an isosceles triangle must be equal. Taylor was going through the demonstration, but was interrupted by Blake exclaiming, ‘Ah, never mind that—what’s the use of going to prove it? Why, I see with my eyes that it is so, and do not require any proof to make it clearer.’”10

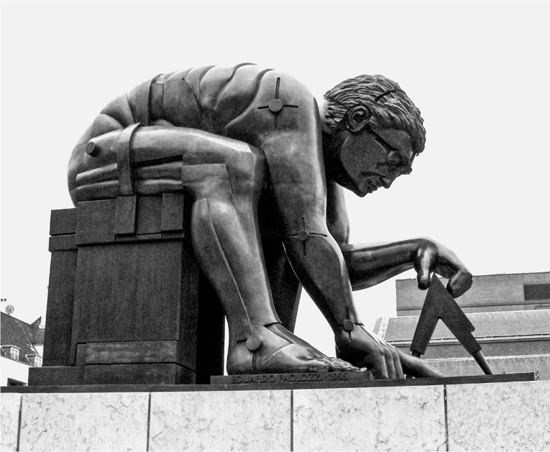

29. Newton, by Eduardo Paolozzi

A note about the process by which Blake produced this print can add to our appreciation, and it accounts for the striking contrast between the enamel-like human form and the blurry vegetation. A painter friend of his explained how it was done:

When he wanted to make his prints in oil, he took a common thick millboard, and drew in some strong ink or colour his design upon it strong and thick. He then painted upon that in such oil colours and in such a state of fusion that they would blur well. He painted roughly and quickly, so that no colour would have time to dry. He then took a print of that on paper, and this impression he coloured up in watercolours, repainting his outline on the millboard when he wanted to take another print. This plan he had recourse to because he could vary slightly each impression; and each having a sort of accidental look, he could branch out so as to make each one different. The accidental look they had was very enticing.11

Blake has thus given visual embodiment to the contrast between the clarity of the human form and the confused, stifling materiality of the world as Newton and the empiricists conceived of it.

In modern times Blake’s Newton inspired a remarkable sculpture by Eduardo Paolozzi (figure 29), erected in 1995 outside the British Library in London. Constructed of weighty metal plates that are visibly bolted together, and peering through tight-fitting eyeglasses that resemble goggles, this Newton provides a thought-provoking reimagining of Blake’s picture. A commentator calls him “a three-dimensional machine man,” reinforcing Blake’s critique of Newtonian science by emphasizing its artificiality.12