WHEN he created the Lambeth Books, particularly The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Visions of the Daughters of Albion, and America: A Prophecy, Blake was a man with a social message. At Felpham he became convinced that he was more than that: he felt called to be a prophet in the line that stretched from Isaiah and Ezekiel through John of Patmos. “Mark well my words!” he exclaims in Milton, “they are of your eternal salvation.” And in Jerusalem he testifies, as his predecessors had, that the prophet’s obligation is heavy:

Trembling I sit day and night, my friends are astonished at me,

Yet they forgive my wanderings, I rest not from my great task!

To open the eternal worlds, to open the immortal eyes

Of man inwards into the worlds of thought: into Eternity,

Ever expanding in the bosom of God, the human imagination.

O Saviour pour upon me thy spirit of meekness and love:

Annihilate the selfhood in me, be thou all my life!

Guide thou my hand which trembles exceedingly upon the rock of ages.1

As Blake understood the role of prophecy, it was to give expression to an individual’s perception of truth. No biblical prophet was infallible, far from it. Nor did prophecy cease after the Bible was compiled. Blake regarded Milton as the most recent of the prophets, and as he worked to elaborate his own personal myth, he became obsessed with his great predecessor.

As a feat of imagination, Paradise Lost was exceptionally appealing to Blake. “To paint things as they are,” Samuel Johnson said, “requires a minute attention, and employs the memory rather than the fancy.” That was just the kind of art that Blake despised. But Johnson went on to say, “Milton’s delight was to sport in the wide regions of possibility; reality was a scene too narrow for his mind. He sent his faculties out upon discovery, into worlds where only imagination can travel, and delighted to form new modes of existence, and furnish sentiment and action to superior beings, to trace the counsels of hell, or accompany the choirs of heaven.” Blake would agree with all of that, except to insist that the world of imagination is the true reality, not an escape from it.2

In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell Blake had criticized Milton’s theology but honored him as “a true poet.” At Felpham he began to think about Milton more deeply. William Hayley owned many books by and about Milton, and had written a biography in which he speculated about what would happen if Milton could return to earth to correct mistaken interpretations of his life and writings. That suggestion may well have given Blake the idea of bringing Milton back in a poem of his own. But in Blake’s opinion it was Milton himself, and not just his interpreters, who needed correction.3

Milton begins with a long “Bard’s song” that presents a heavily disguised version of Blake’s spiritual struggle with Hayley. That struggle played itself out within Blake’s consciousness, and in all probability Hayley never suspected it. He was never the real target anyway, since Blake gratefully acknowledged how kindly his intentions were. Insofar as Hayley does play a role in Milton, it is by embodying the conventional worldly expectations that Blake had long struggled against and that he had hoped to be liberated from in Felpham. Disillusionment came when he realized that if he followed Hayley’s advice, he would be in artistic bondage just as much as before.

As the poem’s title indicates, its true target is Milton, whom Hayley was seeking to coopt as self-appointed custodian of his reputation. Blake’s attitude toward Milton was deeply complicated. As creator of a mighty mythic narrative, he was an inspiration; as defender of a repressive belief system, he was an obstacle.

Say first! what moved Milton, who walked about in Eternity

One hundred years, pondering the intricate mazes of Providence.

Unhappy though in heaven, he obeyed, he murmured not, he was silent

Viewing his sixfold emanation scattered through the deep

In torment! To go into the deep, her to redeem and himself perish:

What cause at length moved Milton to this unexampled deed?

A Bard’s prophetic song!

The Bard is an idealized version of Blake; the “sixfold emanation” is Milton’s three wives and three daughters, the collective female counterpart over whom he supposedly tyrannized during his lifetime. Since his death, his spirit has been confined unhappily to the bleak heaven he depicted in Paradise Lost, presided over by a tyrant God who declares imperiously in that poem, “What I will is fate.”4

Blake’s aggressive critique of Milton furnishes one of Harold Bloom’s examples of the “anxiety of influence,” in which a “strong poet” achieves his own vision by wrestling with an intimidating predecessor. Blake himself would have said that he was uniting with Milton, not displacing or rejecting him, and that he was rescuing what was inspired in Milton’s vision by purging it of error.5

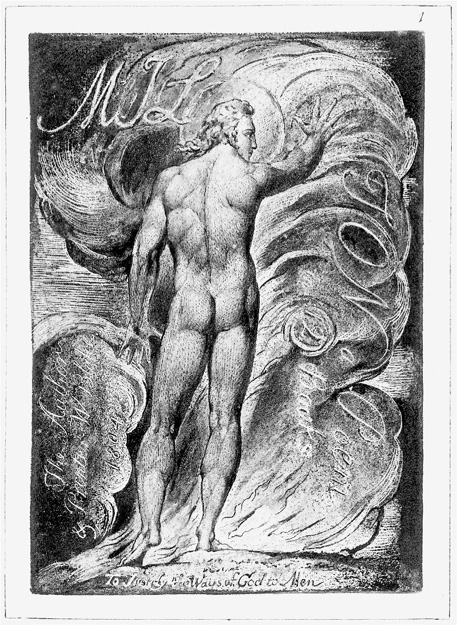

The majestic title page for Milton (figure 33) shows a naked, muscular figure with his back to us, advancing resolutely into flames of renewal. With his right hand he breaks open his name, MIL–TON, pushing forward into our world and into Blake’s poem. At the bottom of the plate his own mandate in Paradise Lost is quoted: “To justify the ways of God to men.”6 Milton believed that he could justify God by showing that humankind is responsible for its own suffering. Blake will seek to “justify” a conception of the divine very different from that of the seventeenth-century Calvinist.

The Milton who wrote Paradise Lost was personally authoritarian, and it is time to free him from his self-righteous ego, or in Blake’s terms from the “false body” of selfhood.

33. Milton, copy C, title page

This is a false body: an incrustation over my immortal

Spirit; a selfhood, which must be put off and annihilated alway

To cleanse the face of my spirit by self-examination,

To bathe in the waters of life: to wash off the not human.

I come in self-annihilation and the grandeur of inspiration

To cast off rational demonstration by faith in the Saviour,

To cast off the rotten rags of memory by inspiration.7

Milton’s immortal spirit lives on, but the ragged garment of his selfhood—the historical Milton, with all his limitations and biases—must be “annihilated.” In the picture that illustrates these lines (color plate 20) he is again naked, as he was on the title page, but now he is facing us. His face is Christlike, and the sun rises behind him while a radiant halo surrounds his head.

Since it is Blake in Felpham who has summoned Milton back to earth, a crucial event in the poem is their direct encounter. It is described, however, in imagery of surpassing weirdness:

Then first I saw him in the zenith as a falling star

Descending perpendicular, swift as the swallow or swift,

And on my left foot falling on the tarsus, entered there;

But from my left foot a black cloud redounding spread over Europe.

Milton the man no longer exists; it is his spirit that hurtles down from the heavens, taking the form of a shooting star and not a person. The star strikes Blake’s foot, perhaps since he thought of feet as our point of contact with the physical world. It is Jesus’ feet that are invoked in the lyric in Milton known as Jerusalem: “And did those feet in ancient time / Walk upon England’s mountains green!”8

Though not always consistently, Blake generally saw negative implications in the left or “sinister” side. With surprising specificity, he identifies the point of contact here as the tarsus. That is the upper part of the foot that joins the ankle, but Blake must have chosen it because it is also a biblical name: Saul of Tarsus was struck down on the road to Damascus and became Saint Paul. The black cloud may be the false elements of Milton’s former beliefs, now dispersing. Or, since the cloud seems to spread from Blake himself, perhaps he too is complicit in errors that must be exposed and rejected.9

The moment of Milton’s descent is illustrated with not one image but two, each occupying a full page. The first (figure 34) is positioned as a divider between the two books of Milton. Blake, identified as “William” in the caption, staggers backward at the very instant when the shooting star, trailing light, is about to strike his foot. In one copy of the poem he is naked; in the other three, as here, he wears diaphanous briefs through which his body can be seen. A number of commentators are convinced that his penis is erect, but if so it is very tactfully represented.10

The other image (figure 35) is altogether surprising. It comes a few plates later, not facing this one as might be expected, but obviously a mirror image of it. Its caption, “Robert,” would have baffled any contemporary viewer, since that name appears nowhere in the poem. This is Blake’s much-loved younger brother, who had died in his teens and whom Blake continued to regard as a kind of alter ego in Eternity. The star may represent Robert’s astral body as imagined in Neoplatonic philosophy, a spiritual projection that can revisit earth from the afterlife.11

A few months before he moved to Felpham, Blake sent a moving letter of consolation to Hayley, whose teenage son had just died after a long and painful illness.

I am very sorry for your immense loss, which is a repetition of what all feel in this valley of misery and happiness mixed. . . . I know that our deceased friends are more really with us than when they were apparent to our mortal part. Thirteen years ago I lost a brother, and with his spirit I converse daily and hourly in the spirit, and see him in my remembrance in the regions of my imagination. I hear his advice and even now write from his dictate—for-give me for expressing to you my enthusiasm which I wish all to partake of since it is to me a source of immortal joy even in this world. By it I am the companion of angels. May you continue to be so more and more, and to be more and more persuaded that every mortal loss is an immortal gain. The ruins of time builds mansions in Eternity.12

All Christians are supposed to believe that their loved ones enjoy eternal life. What is exceptional in Blake is his conviction that Robert has not ascended to some remote heaven, but continues to communicate with him “daily and hourly.” So the letter to Hayley moves from reminiscence—“thirteen years ago”—to “even now” as the words flow from the pen.

It is hard to know how literally to take Blake’s claim that he communicates directly with Robert. Remarks that are scattered throughout his works suggest that the contact must be with Robert’s essential spirit, which lives on in Eternity but is no longer identical with the young sibling who died in 1787. Blake always criticized orthodox preaching that encouraged people to endure suffering in this life with the promise that their individual selfhood would survive unchanged in Heaven. Similarly, as the paired “William” and “Robert” pictures suggest, Blake’s union with Milton is spiritual and symbolic. After it occurs, we do not see Milton walking the earth with Blake as a novelistic character might. And in any case, the heart of the poem is not so much Blake’s union with Milton as Blake’s union with Los.

Los first made his appearance in two of the short Lambeth Books, The Book of Urizen and The Book of Los. In Milton he emerges not as a rebel but as a formidable rival creator to Urizen. Urizen attempts to create after the fashion of the biblical Jehovah: “God said, Let there be light: and there was light.” In contrast, Los creates with intense physical labor, a blacksmith hammering recalcitrant iron on his anvil. This creator is an artist and a craftsman, and in the late Jerusalem Blake imagines himself as an avatar of Los, a blacksmith who uses the Thames as the trough in which to cool the molten metal:

Round from heaven to earth down falling with heavy blow

Dead on the anvil, where the red hot wedge groans in pain,

He quenches it in the black trough of his forge; London’s River

Feeds the dread forge, trembling and shuddering along the valleys.13

The “he” in this passage is Rintrah, one of the sons of Los, who was associated in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell with prophetic wrath.

In conceiving this blacksmith creator, Blake may well have been thinking of Hephaestus, known to the Romans as Vulcan, the artificer of Olympus who creates the great shield of Achilles. But most important, surely, was Blake’s own experience as an artist and craftsman. A writer like Shelley could think of creativity as wholly mental: “The mind in creation is as a fading coal which some invisible influence, like an inconstant wind, awakens to transitory brightness.” But Blake’s poems were not fully realized until sharp tools had gouged them into copper plates or until acid had raised the metal outline into relief—“melting apparent surfaces away, and displaying the infinite which was hid,” as he says in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell.14

34. Milton, copy C, plate 31

35. Milton, copy C, plate 36

Still, even if Blake was a worker in metal, a tidy engraver’s studio is very different from a hot and smoke-filled smithy, such as he and his contemporaries would have seen constantly—even in the city, horses needed to be shod. It must have been the blacksmith’s associations with flames and muscular energy that appealed to Blake. Perhaps he was thinking of a well-known series of paintings, all entitled A Blacksmith’s Shop, by Joseph Wright of Derby. In the most striking of these, a glowing forge stands out from a shadowy background, and at the center a white-hot metal bar lies beneath the blacksmith’s hammer. Blake may also have remembered Ben Jonson’s use of blacksmith imagery in his tribute to Shakespeare, which likewise captures the heat and effort of the forge, as well as the effect of creation on the artist himself:

And that he

Who casts to write a living line, must sweat . . .

Upon the muses’ anvil: turn the same,

(And himself with it) that he thinks to frame.

At the end of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Stephen Dedalus invokes the same analogy, with a moral emphasis that is very Blakean: “I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.”15

As with Blake’s other invented characters, no one knows how he pronounced “Los.” The name is suggestive of “loss,” and may have been pronounced that way, though it seems easier somehow to make it rhyme with “close.”

Just as the other Zoas do, Los experiences a fall when Albion slips into nightmare; that was when all four Zoas, together with their emanations, broke apart into competing entities. In Eternity, where he represented the unfallen imagination, he was known as Urthona, and the very presence of the new name is a symptom of the disaster.

What, exactly, Los is falling from is not made clear, since Blake never tries to describe the mysterious life of Eternity or what the Eternals themselves might be like. Their mode of existence is drastically different from our own, so we can only guess at it; at the end of Jerusalem Blake describes the unfallen Zoas as “the four living creatures, chariots of humanity divine, incomprehensible.”16 For that matter, Albion himself is none too easy to understand. Although all four Zoas were once fully integrated within him, they are now bitterly divided, and their quarrelsome interaction is what fills the poems.

One of the final Lambeth Books, The Book of Los, published in 1795, describes Los’s fall in verse that is tumbling and unstable:

Falling, falling! Los fell and fell,

Sunk precipitant heavy down down

Times on times, night on night, day on day;

Truth has bounds, error none. Falling, falling,

Years on years, and ages on ages

Still he fell through the void, still a void

Found for falling, day and night without end,

For though day or night was not, their spaces

Were measured by his incessant whirls

In the horrid vacuity bottomless.17

The vertiginous fall threatens to go on forever, since error has no bounds. Los tumbles through the void for “ages on ages,” before time as we know it even exists—“day or night was not.” But as he spins it is he himself who begins to define day and night, “measured by his incessant whirls.”

In Blake’s myth, Los is consistently associated with the measurement of time. While he was falling he measured time involuntarily, but was somehow able to arrest his fall; thereafter he measures time more constructively with rhythmic blows of his blacksmith’s hammer. Blake is not a narrative poet in any conventional sense, and we are not told how the change from fall to reconstruction takes place. Perhaps it can’t be narrated; it is a psychic turn that is felt but not fully understood.

Los had already appeared as a blacksmith measuring time in The Book of Urizen, published one year before The Book of Los:

The eternal prophet heaved the dark bellows

And turned restless the tongs, and the hammer

Incessant beat; forging chains new and new,

Numb’ring with links hours, days and years.

The Eternals, whatever they are, inhabit a perpetual Now, but in our fallen world we desperately need the structuring that is given by time. Thus, in Milton:

Time is the mercy of Eternity; without time’s swiftness,

Which is the swiftest of all things, all were eternal torment.18

Terrified by formlessness, Urizen tries to create a world of petrified stability. Los rightly breaks it asunder, but that act precipitates his own fall. As described in The Book of Los,

The prophetic wrath, struggling for vent

Hurls apart, stamping furious to dust

And crumbling with bursting sobs; heaves

The black marble on high into fragments.

Hurled apart on all sides, as a falling

Rock, the innumerable fragments away

Fell asunder; and horrible vacuum

Beneath him and on all sides round.

Having smashed Urizen’s rigid and sterile universe, Los wields his mighty hammer to rebuild Urizen himself. In allegorical terms, one might say that imagination comes to the rescue of self-crippled reason.

Los beat on the anvil, till glorious

An immense orb of fire he framed. . . .

Nine ages completed their circles

When Los heated the glowing mass, casting

It down into the deeps, the deeps fled

Away in redounding smoke; the sun

Stood self-balanced, and Los smiled with joy.

He the vast spine of Urizen seized

And bound down to the glowing illusion.19

“Smiled with joy” recalls “and did he smile his work to see” in The Tyger, published just one year previously. In a sense Los, like Urizen, plays the part of a Neoplatonic or Gnostic demiurge who creates the material world. In this unusually short work—The Book of Los has just five plates—the following words all appear: “hands,” “feet,” “immortal,” “furnaces,” “anvil,” “hammer,” “framed,” “deeps,” and “seizing.” That is the very same vocabulary as in The Tyger.20

As usual with Blake, there are multiple versions of every “event,” and in an account in The Book of Urizen there is no smiling Los:

A vast spine writhed in torment

Upon the winds; shooting pained

Ribs, like a bending cavern

And bones of solidness, froze

Over all his nerves of joy.

Exhausted by the effort and horrified at the hideous creature he has fabricated,

In terrors Los shrunk from his task:

His great hammer fell from his hand.

The image that illustrates these lines (color plate 21) shows Los experiencing the “dismal woe” that is described just above the image, with a huge fluted column projecting weirdly from his body. It seems grotesquely phallic, and architectural as well; Erdman thinks it’s a leaning tower like that of Pisa, about to topple over. We don’t see the “vast spine” and ribs mentioned in the poem, but Urizen is indeed shockingly skeletal, with neck vertebrae disturbingly visible. Still, the work of reconstruction is under way, and as David Bindman says, he is now “sentient enough to agonize in the flames of the forge.”21 His ankles are shackled to the ground.

There are many ways to imagine creativity, and the blacksmith’s labor is not the only one. Further on in The Book of Urizen, Los somehow extrudes a globe of organic “life blood” from his head:

The globe of life blood trembled

Branching out into roots,

Fibrous, writhing upon the winds;

Fibres of blood, milk and tears,

In pangs, eternity on eternity.

Anatomists at the time understood the organs to be composed of fibers, and they identified three different types of fluid-bearing vessels. These were blood, lacteals, and tears—the very ones that emerge from Los’s bloody globe. In the picture that corresponds to these lines (color plate 22) he presses his hands forcibly against his head while his hair drips down upon the globe like bloody rain.22

In still another poem on this theme, The Song of Los, published in the same year as The Book of Los, a weary Los is depicted at rest with a blood-red sun before him (color plate 23). Here he seems melancholy and even tender, though oddly chubby. The just-created sun gives off crimson beams, while a greater source of light and energy spills from beyond it. Los is a creator, but he is not the creator. Creation is an ongoing expression of energy, not the primal event described in Genesis.

In the densely colored images in the books of this period there is no etching at all, just paint laid directly on the plate and touched up as needed after printing. Robert Essick describes what can be seen in the particular copy that is reproduced here:

The design is built up by multiple layers of color printing, painting, and perhaps blotting. The major elements of the design were printed in thick, opaque colors that formed large dendritic patterns. These can be seen in areas untouched by subsequent layers, such as the background and just below the figure’s left knee. The man and hammer were then painted with thick colors, but the suns received further printings or blottings. Below the hammer are a number of short hairs stuck to the paper—very likely the remains of a stubble brush used to daub on colors. . . . Subsequent layers of color shimmer above the paper to form a “glowing illusion” like the sun described in the Book of Los.23

In reproduction, unfortunately, these subtle effects disappear.

When he was first imagining the role of Los, Blake concentrated on mythic origins. In Milton and in its sequel, Jerusalem, Los enters our world, and in the frontispiece to Jerusalem (figure 36) we see him doing so. He is dressed as a night watchman; the sun is now a “globe of fire,” not blood, and serves as his lantern. Strange dark rays shine from inside the archway, and a wind blows Los’s hair and clothing to one side. His hat is a broad-brimmed one such as Blake himself was accustomed to wear, and his garment—blue in the sole colored copy of Jerusalem—is perhaps a printer’s smock. One item is hardly British, however: the sandal, which for Blake symbolizes prophetic vocation. And again we hear of the left foot, which in Milton was the place where Milton’s spirit entered Blake as a falling star. Here he speaks in his own voice:

All this vegetable world appeared on my left foot

As a bright sandal formed immortal of precious stones and gold;

I stooped down and bound it on to walk forward through Eternity.

“Sounds solid,” Stephen Dedalus reflects as he walks with eyes closed on a Dublin beach, “made by the mallet of Los Demiurgos. Am I walking into eternity along Sandymount Strand?”24

Los’s left hand is raised in a gesture that is hard to read. Is he registering apprehension? Just keeping his balance? He is gazing to the right; what does he see that we can’t? Above the archway some lines of verse were originally engraved, deleted from the printed version but recoverable from a proof sheet, and one of them describes this moment: “He entered the door of death for Albion’s sake inspired.”25

Two biblical texts help to clarify the significance of the watchman. One is in Isaiah: “Watchman, what of the night? The watchman said, The morning cometh, and also the night: if ye will inquire, inquire ye: return, come.” And since by entering death’s door Los is enacting a Christlike role, the Gospel of John is relevant too: “I am the door: by me if any man enter in, he shall be saved.”26

Just as Milton unites with Blake in Felpham, so does Los, as described at length in a verse letter to Butts. (It is worth remarking that if Blake had not had Butts for a sympathetic correspondent, some of his most memorable statements and poems would not exist.) Setting out from Felpham to meet his sister, who was coming from London for a visit, Blake finds the way threateningly blocked by family demons:

36. Jerusalem, copy E, frontispiece

With my father hovering upon the wind

And my brother Robert just behind

And my brother John the evil one

In a black cloud making his moan,

Though dead they appear upon my path

Notwithstanding my terrible wrath.

They beg they entreat they drop their tears

Filled full of hopes filled full of fears,

With a thousand angels upon the wind

Pouring disconsolate from behind

To drive them off, and before my way

A frowning thistle implores my stay.

What to others a trifle appears

Fills me full of smiles or tears,

For double the vision my eyes do see

And a double vision is always with me.

With my inward eye ’tis an old man grey,

With my outward a thistle across my way.

“If thou goest back,” the thistle said

“Thou art to endless woe betrayed,

For here does Theotormon lower

And here is Enitharmon’s bower

And Los the terrible thus hath sworn

Because thou backward dost return

Poverty envy old age and fear

Shall bring thy wife upon a bier.”27

(“Theotormon” here is one of the sons of Los.)

This is a vision, not a hallucination. But if to other people a thistle is just a thistle, to Blake it looms as a figure of stern reproof, accusing him of failing to support his depressed and sickly wife. Catherine was ill a good deal of the time at Felpham, and Blake evidently felt that she was reproaching him for failing to bring in more income—but the way to do that would be to abandon his original work and to drudge full-time at tiresome commissions secured by Hayley. By invoking Los, the thistle uses Blake’s own mythic character against him, provoking a crisis of self-doubt. He passes the test and kicks the thistle aside. Suddenly an epiphany bursts upon him:

Then Los appeared in all his power;

In the sun he appeared descending before

My face in fierce flames; in my double sight

’Twas outward a sun, inward Los in his might. . . .

With the bows of my mind and the arrows of thought,

My bowstring fierce with ardour breathes,

My arrows glow in their golden sheaves.

My brothers and father march before,

The heavens drop with human gore.

Now I a fourfold vision see

And a fourfold vision is given to me.

’Tis fourfold in my supreme delight

And threefold in soft Beulah’s night

And twofold always. May God us keep

From single vision and Newton’s sleep.

Strikingly, the family members are all male. There is no mention of Blake’s mother, or for that matter of the sister who is about to arrive. And why do the heavens drip with “human gore”? Has Blake wounded the familial blocking figures with his arrows of thought?

At any rate, the mandate must not be refused, and the bow and arrows are the ones that Blake will invoke again in the lyric that introduces Milton: “Bring me my bow of burning gold, / Bring me my arrows of desire.” When this episode is recapitulated in Milton, the relatives and the blood are no longer mentioned.

While Los heard indistinct in fear, what time I bound my sandals

On, to walk forward through Eternity, Los descended to me,

And Los behind me stood, a terrible flaming sun, just close

Behind my back. I turned round in terror, and behold,

Los stood in that fierce glowing fire; and he also stooped down

And bound my sandals on in Udan-Adan. Trembling I stood

Exceedingly with fear and terror, standing in the vale

Of Lambeth: but he kissed me and wished me health,

And I became one man with him arising in my strength.

’Twas too late now to recede; Los had entered into my soul:

His terrors now possessed me whole! I arose in fury and strength.28

This moment is illustrated by a full-page design (color plate 24) in which an impressively muscular Blake—as usual, blond—pauses from strapping on his sandal and turns “in terror” as Los steps forward out of the sun. (Commentators suggest that his name implies the sun—sol, its Latin name, spelled backward.) Why is Blake’s head positioned at the level of Los’s crotch? Mitchell long ago suspected “homoerotic implications,” while a more recent commentator objects that the conjunction of head and loins may be merely a botched attempt to suggest three-dimensional depth. Christopher Hobson, in his judicious Blake and Homosexuality, argues that Blake was tolerant of all sexual practices but not personally homosexual, and points out that in this picture “Blake’s posture of twisting to face someone behind him is an unlikely configuration for an actual sexual act or kiss.”29 But even if, as does seem likely, no literal sexual encounter is implied, the location of the head is surely not accidental. As in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell and in America, energy is libidinal, and Los is transmitting that potency to Blake.

Painful though the struggle was, Blake has accepted his prophetic calling—but that is only the beginning. Acting as an avatar of the inspiring Los, he must now strive to bring about a breakthrough into Eternity. Each of the three major prophecies—The Four Zoas, Milton, and Jerusalem—ends with an apocalypse, which is described in imagery from the Book of Revelation that was once familiar to everybody, as in “Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord; / He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.” According to Revelation, that apocalypse lies in the future, when the entire universe will end. In Blake’s myth it is an interior Last Judgment that takes place “whenever any individual rejects error and embraces truth.”30 It is thus constructive, not destructive, apprehending Eternity within the world of time.