War and reconstruction

Ever since the American revolution the shadow of renewed hostilities had hung darkly over British North America. Perhaps little attention to such a threat was paid by many of those absorbed in the compelling task of establishing themselves in the pioneer province of Upper Canada; but to officials and others who followed public affairs signs of approaching collision were too evident to be ignored. It may be that international disputes over border towns and the allegiance of Indian tribes could have been resolved peacefully, but Britain’s deep involvement in war with revolutionary and Napoleonic France aggravated the situation in more ways than one. While both belligerents imposed restrictions on neutral trade, the British ones were those that were felt because they could be enforced by sea power. Yet that very naval strength depended on a sufficiency of seamen, many of whom were escaping to the more attractive employment on American ships. The British government, convinced that the leak had to be plugged at all cost, caused American vessels to be stopped at sea so that deserters – or men claimed to be deserters – might be removed by force. By 1812 at least six thousand sailors had been recovered. It seems reasonable to assume, too, that Britain’s preoccupation with Europe affected the issue in another way: the United States, divided in opinion and militarily weak, would have been less ready to make war on an England not handicapped by other commitments.

Be that as it may, the United States did declare war in June of 1812, albeit by a narrow margin in the Congress. In the House of Representatives the vote was 79 to 49 and in the Senate 19 to 13; and it was significant for the conduct of the war that the division was largely geographical, opposition being strong in New England and New York. The country was in other ways unready for war. The regular army had shrunk to a skeleton and recruits were elusive even when sought. The militia, with little training, was in many cases lacking in enthusiasm and sometimes its employment was restricted by state regulations. The central government was as yet without adequate authority, and even when it did issue commands they were, in the early campaigns, to generals with limited competence.

On the high seas the Americans had some success in minor engagements and with privateers, but they had no fleet able to meet a large British force. Thus the maritime provinces were safe from attack and the Canadas could be supplied through the St Lawrence. In the first year of the war, too, the British held a strong position on the Great Lakes, the continuation of the St Lawrence route. The Provincial Marine had been used mainly as a transport service and did not rank high by naval standards, but its armed vessels were superior to anything the Americans possessed at the beginning; and of course it continued to be valuable for moving troops and supplies. The British weakness lay in the small number of regular regiments that could be assigned to the Canadas in view of the demands of the European theatre; and for what units could be spared the first priority was Lower Canada. If it fell Upper Canada would follow automatically.

Few as they were, the regulars in Upper Canada formed the hard core of the defensive forces. That the people of Upper Canada turned out as a man to defend their homeland is a myth that has long since been exploded. Loyalty, indeed, was a scarce commodity, and especially west of Kingston. The open-door immigration policy inaugurated by Simcoe may have brought to the province some so-called late United Empire Loyalists, but more conspicuously it allowed the entrance of those loyal only to their own interests. They came for free land, and the oath of allegiance that they took was all too often meaningless. Brighter spots showed here and there. When Brock asked in York for volunteers to serve against the invaders more men stepped forward than he could transport, and so he could accept only one hundred of those who were ready to fight. Such a response, however, was not general. In some areas individuals defected to the enemy or militia units simply refused to come out on duty. In other cases the militia was half-hearted, more concerned with the immediate harvest then defence of the land on which it grew. On the other hand some militia companies fought well, especially if stiffened by the presence of regulars.

The state of opinion in the province was bad enough but an exaggerated version of it gave rise to the American belief that no more was needed than to ‘liberate’ an oppressed people. The Upper Canadians, the argument ran, would welcome an opportunity to throw off British rule. With that in mind the American government was anxious to treat civilians gently, as friends rather than foes (just as the British thought it wise not to needle New England or New York into a more militant spirit). General Hull’s proclamation from Sandwich was intended to implement this policy: ‘Raise not your hands against your brethren… You will be emancipated from tyranny and oppression and restored to the dignified position of freemen.’ That sort of language had been tried in 1776 without much result, but the appeal in 1812 was to those who had come from the United States not long before and the effect was considerable.

Psychological warfare, to use the modern expression, was pursued with some success but the pen could not altogether replace the sword. American military authorities were aware that their main objective should be to cut British communications as far east as possible. In his classic Sea Power in Relation to the War of 1812 Admiral Mahan stated the issue succinctly: ‘The Canadian tree was rooted in the ocean, where it was nourished by the sea power of Great Britain. To destroy it, failing the ocean navy which the United States had not, the trunk must be severed; the nearer the root the better.’ That was accepted in Washington and by the generals – in principle but not in practice. Sir James Yeo, British commander of naval forces on the lakes, commented after the war that Britain owed much to ‘the perverse stupidity of the enemy,’ and by that he meant primarily failure to follow the strategy so obviously required. Quebec, it was true, could be strongly defended and Montreal only less so, and there was little stomach for an attack on either.

Kingston was not close to the root of Mahan’s tree, but still on the trunk and American possession of it would deny British access to the lakes and thus make it virtually impossible to hold Upper Canada. With this in mind the American strategic plan for the spring of 1813 was to mount from Sackett’s Harbour, the American strongpoint opposite Kingston, an attack on the latter, followed by moves against York and then Niagara. The plan was sensible but on second thoughts was turned upside down on representations to the secretary of war by the army and navy commanders, Dearborn and Chauncey. Claiming, on the basis of false intelligence, the presence of regulars in Kingston far beyond their actual strength, Dearborn asked to postpone the major task and begin with York. The object, according to his letter,1 was to secure command of Lake Ontario by capturing or destroying the armed vessels at York; and, indeed, in the delicate balance of naval power, a vessel or two might turn the scales. In the afternoon of 26 April the American fleet was sighted from Scarborough Bluffs.

And so the war came to York, a town in almost every respect unprepared for battle. Its significance in the war was confused by compromises. It was, temporarily, the capital of the province; but the lieutenant governor remained in England throughout the war, and the administrator, as commander-in-chief, was wherever the campaigns led him. Members of the assembly seemed to be mentally incapable of comprehending the dangers to the province and any interruption of their proceedings would have involved no loss. Strongly patriotic citizens were balanced by those actually or passively disloyal.

Apart from being a source of supplies York had some other part in functions relating to the war. One was that it was on a route to the northwest which was still in the stage of planning and development when hostilities broke out. In previous months it had seemed reasonable to suppose that this way of avoiding the American border would be valuable in wartime. Early in 1812 Captain A. Gray, the acting quartermaster general, had talks with the North West and Michilimackinac companies assuring them of the interest of the governor general, Sir George Prevost, in the protection of trade. The representatives of both companies said that in the event of war they would go by York instead of Detroit. So far as is known, however, they made no use of Yonge Street during the war. Governmental authorities were also interested in the movement of troops and military supplies and in communications, and for those purposes Yonge Street did prove to be of value. The reinforcements for Michilimackinac, for example, consisting of two hundred soldiers from Kingston, proceeded up Yonge Street to Lake Simcoe in 1814.

An argument had started over the use of York as a dockyard and naval base before the town was founded and the controversy continued. In March 1812 Gray looked nervously at the concentration of naval and ordnance capacity in Kingston and inclined toward York as less vulnerable and yet having a good harbour. Unlike Kingston it was far from any of the potential bases of American strength and could be defended.

The most important consideration is the safety afforded against any Coup de Main of the Enemy. York will in all probability be held as long as we have a foot of territory in Upper Canada, as from its remote situation, and being so far retired from the frontier, it can be secured from any sudden assault; nothing therefore can affect it but operations having for their object the subjugation of the Province, and which object this Post is admirably calculated to defeat, if it were fortified in a proper manner and well garrisoned.2

All this had been said so often but it never seemed to penetrate. As it was York was given enough role as a shipyard and naval base to make it a target for attack but never the means of resisting. In the winter of 1813 construction began on what was to be one of the largest fighting ships on the lakes, Sir Isaac Brock. General Sir Roger Sheaffe, commander after the death of Brock, urged, only a month before the American landing, that York be ‘put into a more respectable state of defence’ in view of the likelihood that the Americans would seek to destroy a ship that could be decisive on Lake Ontario.

In April 1813 York was a sitting duck. The town, at the east end of the bay, had a simple blockhouse near the water’s edge. From there a broken line of houses extended about a mile to the west. Beyond that was an open space followed by the mouth of Garrison Creek. At that point a fort had been started but only the magazine finished. Close to the lake were two twelve-pounder guns behind earthworks. The Western Battery was some hundreds of yards beyond that and consisted of two eighteen-pounder guns. These were, however, of little value. They had long since been condemned and were without gudgeons, that is to say they could not be pivoted, only fired from a fixed position and for a fixed range. The troops in York were under the command of Sheaffe, who happened to be there at the time. The regulars amounted to about three hundred men, consisting of two companies of the 8th or King’s Regiment; a detachment of the Royal Newfoundland Regiment, of company size; and a company of the Glengarry Light Infantry Fencibles (that is, a regular regiment raised locally). To that were added companies of the 3rd York Militia Regiment and something over fifty Indians.

The American fleet consisted of fifteen ships of various sizes, some being heavily armed. Some seventeen hundred soldiers were aboard. On the morning of 27 April the indications were that the landing would be near old Fort Rouillé. Sheaffe therefore sent toward that point the Glengarry Light Infantry and the Indians. The former somehow lost their way although there was a road of sorts. Dearborn had indeed picked on Fort Rouillé, but a strong east wind drove the boats some distance beyond that and the landing was made on a wooded shore. Contemporary accounts, being partisan, differ. Chauncey claimed that as the schooners beat into position they were ‘under a very heavy fire from the enemy’s batteries.’ In view of the antiques with which the gunners were struggling it seems improbable that whatever fire there was did much harm. On the other hand there is more solid evidence that the grapeshot fired from the ships was a considerable aid to the landing parties.3

The first American unit to land, opposed by Indians, the only defenders nearby, scrambled on to the high ground. The grenadier company of the 8th Regiment hurried to the scene, tried to counterattack, but the odds were too great and they had to back toward the Western Battery. There, where other troops had assembled, a small portable magazine blew up by accident, killing and wounding several men and handicapping those who had been using it. The retirement continued to Garrison Creek and Sheaffe concluded that, against forces greatly superior in numbers and weapons, he could do nothing, and that he could save his troops only by abandoning York. He had already lost sixty-two killed and ninety-four wounded. Before withdrawing toward Kingston he ordered the destruction of the main magazine and the warship on the stocks, and left to the militia officers the negotiation of a capitulation.

The militia had barely been in the engagement but some of its officers, together with civilians, were bitterly critical of Sheaffe’s handling of the engagement and particularly of the surrender of the town. Extreme things were said and written. W. D. Powell, who was away from York, first wrote a measured account including modified praise for Sheaffe, but later – probably after his return – joined in the chorus of condemnation. A strange document, preserved only in a draft in the hand of John Strachan, the new rector of York, is dated 8 May 1813. It was signed by Strachan himself, Lieutenant Colonel William Chewett, Major William Allan, and Captain Duncan Cameron, all of the 3rd Militia Regiment; also by Alexander Wood, Samuel Smith, and W. W. Baldwin. Thomas Ridout signed but on second thoughts scratched out his signature. There is an indication that the sheriff, John Beikie, refused to sign. The letter was to be sent to John Richardson, a member of the executive council of Lower Canada, with the suggestion that it be shown to Governor General Prevost and then published.

It is a foolish document, more like childish tantrums than an expression of adult opinion. None of the signatories, Strachan least of all, had any serious knowledge of military affairs and they wrote in the mood of what sports writers call a Monday morning quarterback. There was room for criticism of Sheaffe of course. Brock, whose death at Queenston Heights in October 1812 was a tragic loss, would have acted with more precision and vigour; but to claim that York could have been held is sheer nonsense. To suggest that a town defended by a few obsolete cannon and three hundred regulars, with the shaky support of an equal number of inexperienced militia, against an invading army of seventeen hundred supported by powerful guns on ships that moved at will, is absurd. It is probable that the Americans had no intention of holding York. What they could gain there would come from a short stay, and as it turned out they gained little and suffered substantial losses, mainly from the explosion of the magazine. The shower of rocks killed General Pike with thirty-eight soldiers and wounded 222 men. A last ditch stand by the little British force would have served no useful purpose, while on the other hand it was essential to preserve what few regulars there were in Upper Canada.4

York was left under an army of occupation. The militia officers who had been instructed to settle terms had the energetic support of Strachan, who also secured better treatment of the wounded and prisoners and protection of private property. The capitulation contained three points: that regular, militia, and naval personnel – other than surgeons – become prisoners of war; that naval and military stores be given up but private property be guaranteed to citizens; and that papers of the civil government be retained by its officials. Since the American ships were already overloaded the militia prisoners were paroled. Apart from looking after the wounded the only problem that the citizens had to face was to ensure that the promise of preserving private property was honoured. On the face of it this would seem to mean against looting by the American soldiery; and there was some of that, especially in houses abandoned by their owners, although the American officers did what they could to stop it. The bizarre factor, however, was that not a few of the citizens were as active in looting as were the American privates, and the magistrates could do nothing to stop them. The height of absurdity was reached when the Americans hired nearby farmers to cart to the dock stores from the commissariat, paying them by a proportion of what they carried. Meanwhile the legislative buildings were set on fire, and it is consistent with what had already assumed something of the nature of a comic opera that there is still a dispute as to whether the fire was set by Americans or Canadians. The balance of evidence points toward the former but no definite proof has been found.

The Americans left as soon as they could, partly because there was no point in remaining, partly because they could not be sure that their ships were free from attack. What had they gained? Some government funds were picked up, having had no proper protection, but largely in army bills which might not be easy to cash. They collected a good deal of liquor, and took or destroyed what military supplies and food they could. Success no doubt raised the morale of their militia, though tempered by unexpectedly heavy casualties. They did eliminate the ship under construction, but the Prince Rupert had sailed from York shortly before they arrived, and while the Duke of Gloucester, at York under repair, was towed away it turned out to be unseaworthy.

The capture of York had no major effect on the course of the war other than to divert attention from Kingston, the proper target. The people of the town suffered little. Five Canadians were killed, two of them by the explosion, and five were wounded. Goods were taken from shops and some articles stolen from houses. On the other hand many of the American officers and men fraternized with the inhabitants. With unconscious irony Mrs Powell wrote to her husband that ‘the Fleet so hostile to our comforts departed on Saturday morning.’

York was in a curious state of mind during and after the occupation. The militia officers complained that their force could have performed to advantage if it had been given a chance, but what part it played in the attempt to hold back the Americans gave no evidence to support that claim, and the men seemed to go on parole without regret. Behind the criticisms that have been mentioned lay the assumption that this was a British war fought (to their inconvenience) on the soil of Canadians, and indeed there is a case for such a position. It followed that the British were responsible for winning the war and defending this particular town. The corollary was that Britain should make compensation for loss of property, which to some extent it did.

The occupation left other worries. One arose out of the revelation of disloyalty and of lawlessness in the forms of theft and vandalism. Men were charged in court but in few cases would juries convict. It was also uncomfortable to realize that York, with its militia paroled and defences destroyed, could be captured at will, subject only to naval power on Lake Ontario. The sight of sails caused alarm. A second landing was in fact made at the end of July, and there are indications that renegade Canadians passed word on the location of government stores to be had for the asking. Certain it is that some Canadians helped the Americans in their search for loot, although others frustrated their efforts. Those who liked to call themselves ‘the principal inhabitants’ had retreated into the woods. In September ships were again seen to be bearing on York, but they sailed away.

Neither losses nor hardships throughout this disturbed summer were sufficient to put a heavy drag on the progress of the town, but a major disaster loomed as a result of the war and was narrowly averted. In 1815 the British government decided to move the capital of the province to Kingston, influenced in the main by the proven vulnerability of York. It had never, of course, been intended that York should be the permanent seat of government. Simcoe’s choice of London was not reaffirmed and Kingston, which had frightened off the enemy and was still the largest town in the province, seemed to be the best bet. Loud and indignant cries came from the officials. They recalled with pride that they had heroically accepted the primitive conditions of York where they had selflessly established themselves at high personal cost; and now it was proposed that they should abandon their hard-won homes. Most unreasonable. Halfway through a memorial on the subject5 they just remembered to refer to the overriding importance of the public interest, only to drop back into the arithmetic of what they would lose financially by another move. Why some of the junior employees might even resign! Happily for them and for the town Francis Gore, the lieutenant governor, back at his post with days of peace, was persuaded that the change would be unwise and he induced London to reverse its decision. That did not end the argument, but in fact the government stayed in York throughout the life of the Province of Upper Canada.

That York should remain the capital was regarded as important not only by the personnel of government, who were concerned with their own welfare, but also by the laymen of the town. It was an asset, but one of proportionately decreasing value as the town went through a more general development in the twenty years after Waterloo. During the period of hostilities inconveniences and shortages had existed, caused in part by the dislocation of shipping and in part by the heavy purchasing for the British forces. That very purchasing, although it might have caused some problems for civilian buyers, had brought prosperity to the town and wealth to individual merchants who were more than compensated for damages and appropriation of goods during the few days of military occupation. When the army buying stopped business slumped and prices went down, but a less transitory factor turned the economic curve upward again.

Above all the Province of Upper Canada needed people. It had, not long before, started from scratch as an unoccupied land of lakes and forests. The trickle of people into it had been stopped by the war, during which the population of York and the immediate townships declined. After Napoleon had finally been escorted to St Helena, Upper Canada’s opportunity came. Peace brought to the British Isles not only its blessings but a serious economic depression which, coming on top of the enclosure movement and the dislocation that accompanied the industrial revolution, caused widespread unemployment and suffering. Emigration appeared to the victims of these circumstances to be the only expedient. A desperate one it was for many families, for they had no funds and few possessions to take to this far land of North America; and anything they may have known of the ocean crossing under the disgraceful conditions of the time would make that seem like a nightmare, as indeed it was. Yet there was a chance of a better future and little enough to lose. In addition to the poverty-stricken were substantial numbers of farmers and artisans, and of middle-class people who had some means but hoped to improve their situation in the new world.6

No exact statistics can be found for immigrants moving into York or the Home District as a whole, but the numbers did climb in the twenties and thirties, bringing a substantial if not spectacular flow of people. In 1816 the population of York was only slightly over prewar level but in 1818 it first edged into four figures, more than doubled in the next decade, and by 1833 was over six thousand. It seemed to some contemporaries that too many people were crowding into the town, quenching their thirst at taverns though they had no jobs, whereas they could have been usefully employed on the land. In 1830 the editor of the York Observer wrote:

We have been in some of the back townships, and have to regret, that the scarcity of hands will occasion very great destruction of the wheat. Hundreds of emigrants have recently arrived, and although unemployed about the town, they refuse to enter the bush! Farmers came in from the back townships and offered 3/9 a day, and board, to labourers, and they could not induce those appealed to, to proceed with them!

Immigration from the British Isles, heavy in comparison to the sparsely populated town and country to which it was attracted, changed also the political and racial complexion of Upper Canada. William Berczy’s plan for large-scale settlement of Germans in the 1790s dwindled to very little, although it did result in establishing some progressive farmers in Markham County, on and near Yonge Street. The other European group, that of French royalists led by the Comte de Puisaye, faded almost to nothing on its lands near Whitby. Americans, of course, had come in large numbers and some of them became good subjects of the king. But in view of the disloyalty of others during the war further immigration from the United States was not encouraged. In any case it dwindled because of the prospects opening in the American west. The number of American negroes was not large, perhaps something over three hundred in 1830. Large-scale escapes had hardly begun.

A few families of York, such as the Robinsons, had been well established in the Thirteen Colonies while others had been there only during the revolutionary war. A strong English contingent in York included the Denisons, Jarvises, Powells, Elmsleys, Boultons, Ridouts, Chewetts, and Cawthras. The Scots were numerous too, some of the prominent ones being William Allan, John Strachan, James Macaulay, Aeneas Shaw, John McGill, Robert Hay (of furniture fame), and W. L. Mackenzie. Many more Irish came a little later, but meanwhile they were well represented by the Baldwins, Willcocks, Sullivans, John Gamble (the army surgeon), the legal Gwynnes, John Carey, and Francis Collins.

Both the Town of York and the country about it were enriched by the flow of immigrants, the one gaining more of the institutions and facilities of an urban centre and the other multiplying cleared farms and hamlets. Integration of town and country was not new; it had always been seen as essential. Now, however, it acquired more substance because of the higher scale of population and because both the rural and urban parties had more to offer. By almost any standard travel between them was difficult, for the province was in no position to make drastic improvements in roads.

In spite of handicaps, however, it is obvious that people did travel in and out of York as a matter of routine. Thomas Magrath’s lovely estate, Erindale, was where Dundas Street crosses the Credit River, and he thought nothing of visiting York. ‘We have frequently,’ he wrote in 1832, ‘occupied the morning at work in a potato field, and passed the evening most agreeably in the ball room at York!!!’7 Mary O’Brien, who before and for a time after her marriage lived on farms between Thornhill and Richmond Hill, made frequent references in her diary8 to visits to York by herself, her brother, her husband, and their neighbours. The drive of over fifteen miles took on the average two to two and a half hours. Occasionally trips had to be postponed because of the state of what was locally called ‘the street.’ Early one December Edward O’Brien had to postpone taking his oats to market until the frost returned, and in another November the road was too bad for even riding.

Ordinarily, however, the people in that area took it as a matter of course that they would go to York for any of many reasons: to see friends, shop, deliver farm products, attend meetings of the legislature, do garrison duty, or see a doctor. At one time O’Brien was going to York every day in connection with some land business. On other occasions he walked to the town, on one of these his wife remarking in a matter-of-fact way: ‘Edward went to York again, and as he has walked I do not expect him to return tonight.’ In general these people seemed to think no more of an expedition to York than do modern residents of northern Toronto of going to the downtown shops. How far this generalization would apply to the humbler farmers as well as to such educated, middle-class families is not clear, but there are many references to waggon loads of grain and other products finding their way to the market. Beyond the Don and Humber rivers, too, settlement was moving forward, changing the appearance of the countryside from the first stage of pioneering to something more like an established agricultural area. Roads – probably no better and no worse than Yonge Street – connected them with York, allowing what in the Upper Canadian standard of the day might be called ready access.

York grew with its hinterland – with it and because of it. The economic life of the town, however, consisted of more than local exchange of goods and services for farm products. In both buying and selling, merchants and merchandise had to cover great distances. Between the end of the war and the collapse of the Montreal fur trade in 1821 the dream of Yonge Street as an artery of the northwest trade had at last some slight reality. The evidence on the amount carried is very slight. Isaac Wilson, a settler on Yonge Street, wrote in the summer of 1815 of seeing ‘waggons to carry goods through the country to the Lakes for the North West Company to trade with the Indians and bringing stores back for Government which were conveyed up at an immense expense during the war.’9 This particular twoway traffic was by its nature ephemeral. If Wilson’s description is accurate – and his letters are sensible – the Nor’ Westers were not bringing down their furs by waggon, and there is little evidence that the company continued this transport on its own whenever what was presumably a cost-sharing arrangement with the government was terminated. The customs records of York for early years after the war show importations from the United States of salt and tobacco consigned to the North West Company and non-dutiable goods may also have passed by this land route. There was, then, some long-haul freight on Yonge Street but there seems to be hardly a reference to it in contemporary newspapers, letters, or diaries. This is significant in view of the publicity before the war when the traffic was only a hope.

In this period, then, Yonge Street was principally used for transport within the area between York and Lake Simcoe. The lake shore route to Kingston and Montreal, however, did carry goods over a long distance in the winter; and in the summer could be traversed the whole way or serve as supplementary to ships. In May 1831 William Weller,10 a prominent operator of stage coaches, advertised summer arrangements:

Mail will leave York Sunday, Tuesday, and Thursday at 5 P.M., sleep at Pickering; leave there at 4 A.M.; breakfast at Darlington; dinner at Cobourg; arrive at carryplace [near Trenton] same evening in time for steamboats for Kingston and Prescott.

The steamboat, indeed, added a new dimension to travel. The Frontenac was the first Canadian-built steamer on the lakes. It was large (740 tons) and well equipped. Its maiden voyage was in 1817, and after an unsuccessful experiment in running to Prescott, the route was established as Kingston-York-Queenston. The fare for the first leg was £3 and for the second £1. Other steamships followed, so that in 1826 the York newspaper, United Empire Loyalist, could express satisfaction with the progress made:

In noticing the first trip of another Steam Boat [the Canada of 250 tons] we cannot help contrasting the present means of conveyance with those of ten years ago. At that time few schooners navigated the Lake, and the passage was attended with many delays and much inconvenience. Now there are Five Steam Boats, all affording excellent accommodation, and the means of expeditious travelling. The routes of each are so arranged that every day of the week the traveller may find opportunities of being conveyed from one extremity of the Lake to the other in few hours.

Sailing vessels increased steadily in numbers and carried most of the bulk freight. More attention, however, was directed to the steamships, partly because they were novel, partly because they captured a growing proportion of the passenger traffic. When Thomas Magrath and his family migrated in 1831 they went from Prescott to York by steamer, in ‘first cabin,’ at a cost of £20. For the benefit of his correspondent in Ireland Magrath remarked that lake travel would have been cheaper by three-quarters if they had chosen a schooner, but that their arrival would then have been dependent on the winds. Sailing vessels carried lumber as freight but steamers used quantities of wood for fuel. In 1828 D’Arcy Boulton the younger made a formal contract with Hugh Richardson of York, master of the Canada, to supply a thousand cords of sound dry pine to be delivered at either one of two docks. Not less than eight cords were always to be on the wharf, and if the Canada was held up for lack of fuel Boulton would forfeit £5 or Richardson could consider the contract void. The price was 6/3 a cord.11

Improvements in the harbour were overdue and now were urgently needed to accommodate more and larger ships and heavier traffic. With the facilities available little could be done to make the western gap less hazardous or to dredge the shifting silt there and elsewhere. Three wharves were constructed in 1816. The King’s Wharf, close to Peter Street, was for military purposes and quite short until its enlargement in 1833 or 1834. Cooper’s Wharf was at the foot of Church Street, and the Merchants’ Wharf, built by a syndicate, at the foot of Frederick Street. The last was 770 feet long and said to have ten feet of water at its extremity. That depth, however, must soon have become inadequate in view of the draught of even the early steamers.

The principal exports through the port were all bulky: wheat, flour, lumber, and potash. The main sales were in Britain, the grain being subject to the vicissitudes of the corn laws. Imports covered a very wide range of goods. They were drawn in the main from the British Isles and secondarily from the United States. For the latter the customs records show such goods as were dutiable. Salt and tobacco were the largest items but other imports were varied: whisky, beer, and cider; chocolates, butter, and apples; pork and hams; hats; spelling books; scythes, mill saws, gunpowder, paint, nails, and plaster; waggons and a little furniture. It is noticeable that several of the commodities were in competition with those commonly produced in the Home District. Waggons, carriages, and furniture were certainly made in York, though they may have been of limited types. Cider, hats, and probably mill saws were also made locally. Pork and hams came in from the nearby farms. No one had to go far to find the breweries of John Farr, John Severn, or the Copland Brewing Company.

Taking into account the unlisted British imports it can be said that York was importing from abroad most of the manufactured articles that it required. A few simple things were made in and near the town in addition to beer: lumber, flour, soap, leather, and some simple iron goods. But York was still preoccupied with trade, for which the growing population in the town and beyond offered greater opportunities. By the thirties some wholesalers could be identified as separate from retailers, the beginning of one of the most profitable activities for many years to come. In some cases retail shops were becoming more specialized but that trend was conspicuous a little later. Mrs O’Brien was struck by the progress of the shops, and after one of her many expeditions to York, in the autumn of 1829, wrote that ‘We found the shops so much improved that it is hardly worthwhile to send for any common things from England or to bring out any stores except for the arts and sciences, which will not perhaps be well supplied for some time to come. For the rest the chances are that you may get them as well here.’

Some of the leading shopkeepers of early days dropped out, Alexander Wood in 1821 and William Allan in 1822. Quetton St George had already returned to France, but left two partners, Jules Quesnel and John Spread Baldwin, to run the business locally and send a share of the profits to him. After five years of what proved to be an unsatisfactory arrangement St George was persuaded to sell out to the other two for cash. Not long after that Quesnel returned to Montreal, leaving Baldwin in charge. In 1819 the firm imported goods from England to the value of £11,000 and from the United States of about £1,500. They invested in land and shipping, and Baldwin turned with particular interest to that most important innovation, banking.12

As business began to revive after the war and then to expand, the absence of banking facilities became more serious. Army bills, being legal tender, had served a useful purpose, but at the end of the war the whole issue was called in for redemption in cash. The need of banks was obvious, but so was the fact that whoever controlled them had powerful instruments in their hands. Montreal, the financial as well as the commercial capital of the Canadas, sought to extend its banks into Upper Canada almost as soon as they existed at home. In 1818 the Bank of Montreal appointed William Allan as its agent in York and the Bank of Canada appointed Henry Drean, a York merchant. At that stage, however, these were agencies rather than branches and appear not to have attempted a general banking business.

Meanwhile York had locked horns with Kingston, which was the most important town of Upper Canada. In 1817 a group of Kingston merchants petitioned the assembly for legislation to incorporate a bank, and a few days later a York group, headed by John Strachan, submitted a similar petition. The first only was acted on, the desired legislation being passed and duly forwarded to London for approval, as the lieutenant governor’s standing instructions required. There, however, it became stuck in what Dickens called the Circumlocution Office, and in 1819 the Kingston men began banking operations as a private association.

The arrival of Sir Peregrine Maitland as lieutenant governor in 1818 allowed the oligarchy, centred at York, to use its not-very-secret weapon. Maitland’s extreme conservatism brought him close to the leading York Tories and in particular to Strachan, the titular leader of the local group seeking a bank charter. After being indoctrinated Maitland dutifully reported to London that the Kingston bankers were untrustworthy and had committed the unpardonable sin of establishing American connections, that in turn suggesting to him the shadow of those impossible people, the Reformers. From the point of view of York all then went well. The Bank of Upper Canada was approved in legislation and the charter came into effect in 1821. Its business was largely in discounting promissory notes and in negotiating bills of exchange. Deposits did not constitute an important feature of banking anywhere in British North America and no interest was paid on them. The bank helped to relieve the shortage of currency by issuing bank notes, the total in circulation in 1825 being of the value of £61,000.

The Bank of Upper Canada was a remarkable organization, imbedded in the government, itself dominated by the ruling group involved in the bank. One-quarter of the stock was to be subscribed by the government, which was to appoint four out of fifteen directors. The others were nearly all members of the executive and legislative councils or associated in some way with the oligarchy. Authorized to do so, the bank established branches and agencies in other parts of the province and beyond. It was a neat monopoly and its stock was regarded as a gilt-edged investment. To maintain its sole rule it resisted further Montreal invaders by legislation making their position impossible. As may well be imagined the Bank of Upper Canada was popular neither with the Reformers nor with the commercial communities of other towns in the province. It made no concession to the former, but Kingston – after the collapse of its private bank (whose methods were, to say the least, peculiar) – finally reached its original objective with the incorporation of the Commercial Bank of the Midland District in 1831.13

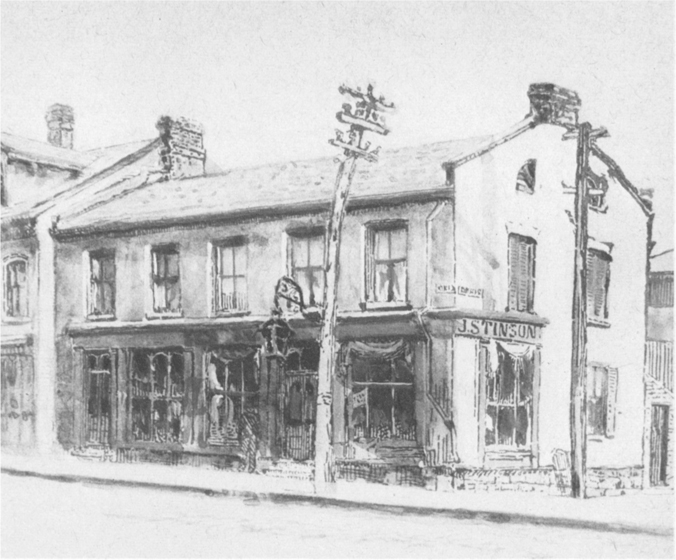

The Bank of Upper Canada, 1821, the first building of the first bank

Another financial institution, closely related to the Bank of Upper Canada, was the British American Fire and Life Assurance Company appropriately situated across the street. William Allan was its governor, and he was president of the bank. J. S. Baldwin was deputy, and on the board were D’Arcy Boulton and William Proudfoot – all, too, connected with the bank. Looking at these financial institutions it would perhaps be fair to conclude that here was the oligarchy at its best and at its worst. The bank and the insurance company made real contributions to the economy and the men connected with them could not be justly accused of maladministration or corruption. They could, however, be convicted of maintaining privilege and securing personal benefit.

Mary O’Brien described the York of 1829 as ‘all suburb … the town is so scattered that I hardly know where the centre may be.’ The better houses were usually in large grounds and for a long time vacant lots added to the appearance of space. She added that on the road along the lake shore were the houses of the ‘principal inhabitants,’ this being in general true but subject to exceptions. While port installations and some small commercial establishments had their places on the bay, the people of the town were determined to maintain the waterfront as partly residential and partly for the enjoyment of the citizens generally. For this latter purpose letters patent of 1818 vested a strip of land next to the bay ‘in John Beverley Robinson, William Allan, George Crookshank, Duncan Cameron and Grant Powell … their heirs and assigns, forever, in trust to hold the same for the use and benefit of the inhabitants of the Town of York, as or for a public walk in front of the said Town.’ Thus began the tortured history of what came to be called the Esplanade.

In a town in which commercial and residential buildings jostled each other, and indeed were often combined, it was symbolic that the road along the shore of the bay should have been divided by the public market at King and New (Jarvis) streets, Palace Street running to its east and Front Street to its west. The market was an important institution which from its origin was designed to benefit both the town and the area around it. More than anything else in York it represented the urban-rural relationship. The market in early years appears to have been entirely out of doors and no record has been found of its appearance or how it was managed. The proclamation of 1803 stated only where sales were to be made and that they were to be each Saturday. Probably the market was interrupted during the American occupation, and it is possible that fear of further invasions discouraged farmers from bringing in produce.

Some months before the end of the war, however, the legislature passed an act (54 Geo. III, c. 15) which was similar to one of 1801 that applied to Kingston. For the convenience of the inhabitants of the Home District a market was to be established, and since there had already been one this must have meant a new and more organized market. The justices of the peace were to choose a location and draw up rules for its operation. Copies of such rules were to be posted in the most public place in each township, and in York on the doors of the church and the court house. The Court of Quarter Sessions duly issued regulations a little over a year later (in April 1815), by which time a wooden building had been erected in the old market square. Both sellers and purchasers were protected. Nowhere else might meat, poultry, fish, butter, eggs, or vegetables be sold between 6 AM and 4 PM. On the other hand tainted meat might not be offered for sale and weights must be accurate. To maintain these and other rules a clerk of the market was appointed and fines provided for violation of any regulation. In 1831 the market was further improved when the wooden building was replaced by a brick one designed by J. G. Chewett and W. W. Baldwin.

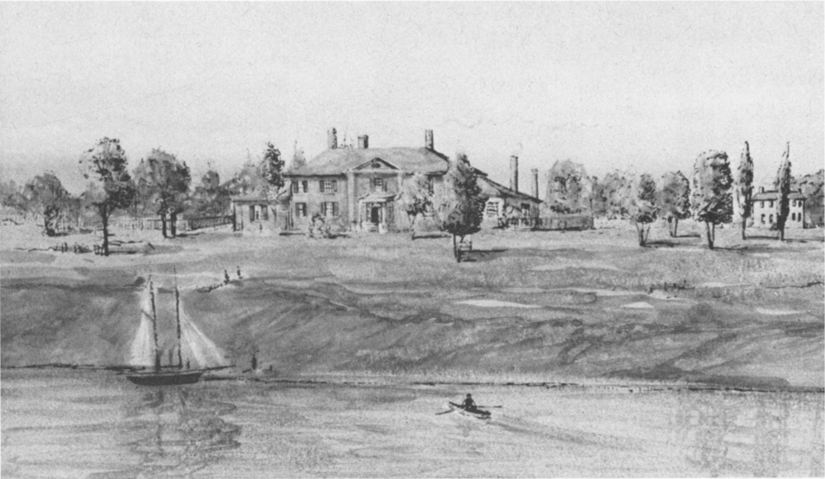

George Crookshank’s residence, northeast corner of Front and Peter streets, erected in 1824

A glance at Palace Street shows that it was becoming more commercial.14 Russell Abbey was half deserted and factories were crowding in elsewhere. Going westward on Front Street good residences began to show from about Church Street. Mr Justice L. P. Sherwood had a view of Freeland’s soap factory, a lumber yard, and a ship carpenter’s yard on the bay shore; but he was flanked by his son-in-law, Dr John King, and a fellow justice of the Court of King’s Bench, J. B. Macaulay. Henry John Boulton, a prominent lawyer, was just east of Bay Street in what the Directory called ‘a newly erected Gothic mansion stucco’d.’ Next door was W. D. Powell. John Strachan had built himself a fine house east of York Street, and there he lived in some style. George Crookshank was at the corner of Peter Street, the western limit of the town. His sister-in-law, on a visit from the United States, found the house pleasant and ‘open to the lake.’ In the garden were pears, apples, cherries, gooseberries, plums, and peaches.

Going back to the east side and inland from Palace Street the houses of several prominent citizens would have been seen. J. S. Baldwin and Alexander Wood lived on Frederick Street. Sir William Campbell, the chief justice, and T. G. Ridout, cashier of the bank, were on Duke Street. The combined properties of S. P. Jarvis, Captain McGill, and William Allan blocked the extension of Lot Street east of Yonge Street.

On the west end of the town three blocks between Graves (Simcoe) and John streets were being turned over to public purposes. From Front to Market (Wellington) Street was Simcoe Place on which were the new buildings for the legislature which had been wandering about unhappily since it was burned out in the southeast. The buildings were ready for occupancy in 1832. Designed by J. G. Chewett, they were simple but dignified and were placed on spacious grounds. In the next block north the Elmsley house had been taken over for a Government House. North of that again was Russell Square on which Upper Canada College was built. Further north again and just within the town limits was Beverley House, rebuilt by J. B. Robinson from D’Arcy Boulton’s cottage. It was a large house and in even larger grounds, for they ran from John to Graves Street and from Hospital to Lot Street. The value of fire insurance on this house gives some indication of the substantial buildings of this period. The policy was for £1,500, with the contents being insured for £300 and the books for another £200.15

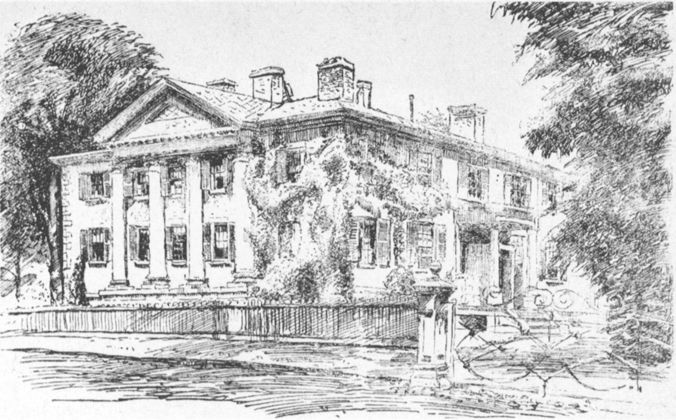

Boulton himself was one of those who chose to live outside the town, although that cannot have been for lack of space within it. The lovely house which he built about 1818, and which has happily been preserved, was called the Grange. It was on park lot 13 which he had bought in 1808 and was entered at Lot Street at the head of John Street. G. T. Denison’s Bellevue, built in 1815, was another handsome house and was between the Grange and the modern College Street. North of Bloor Street and well in the country was Rosedale, built by J. E. Small in 1821 and bought by W. B. Jarvis in 1824. This pleasant house looked across the ravine to Yonge Street which was the western boundary of the property of 120 acres. The whole was considerably smaller than the area named after it. On the east it extended to a line now marked by the lower part of Glen Road; on the north to Roxborough Street; and the southern boundary was irregular, being approximately at the present Elm Avenue. The house was reached from Yonge Street by a ravine road, now Park Road.

W. W. Baldwin followed the example of Peter Russell by living part of his time in town and part in the country. Shortly before the war he built Spadina (Indian for hill) on the brow of the rise at a point just east of the present Casa Loma. The land had been left to the Baldwins by William Willcocks and the house cost £1,500. On the ground floor were two parlours; on the next floor four bedrooms and a study; and in the basement a kitchen, dairy, root cellar, wine cellar, and man’s bedroom. As in the larger house he later built on Front Street no dining room was identified, but presumably one of the parlours served that purpose. The same is true of other old houses in York and also of houses in England of an earlier date.

Moss Park, William Allan’s house on Sherbourne Street, erected in 1830

Within the town it would be difficult to distinguish districts which were residential. Large and small houses, shops, small industries, offices, churches, schools, hotels, boarding houses, and taverns were intermingled. Quite often one building would serve two purposes. A doctor probably always had his office in his residence and merchants had long lived over their shops. One convenient arrangement of the day which saved steps was a ‘Gentlemen’s Boarding House and Liquor Store.’

Taverns were more plentiful than some of those concerned with public morals thought proper, but church buildings came slowly into the landscape. The Church of England still had the largest number of members but not to such an overwhelming degree as formerly. No exact statistics, however, exist.16 The Anglicans were led by their vigorous archdeacon, John Strachan.17 For long St James’ remained the sole church in the town. It was enlarged in 1818 and rebuilt in stone in 1833. To finance the church the practice was to assign pews to individuals who paid for them both lump sums and annual rent. In 1820, for example, Joseph Shaw won at a public auction a pew in the gallery for which he paid £35. The formal document which embodied the terms provided that he and his heirs would continue to have possession subject to an annual rent of £2.18 Complaints were made that little space was left for those who did not own pews.

In spite of their record of missionary work in the province the Methodists found difficulties in establishing themselves in York, and they were slow to do so although for some time preachers who were visiting there addressed ad hoc gatherings. In addition to the need of shifting their focus to urban communities the Methodists were accused of political disloyalty because of early American connections. It proved later that there was scarcely any ground for such charges. Furthermore they were weakened by being split two ways and sometimes more. By degrees their methods were modified and they came to enjoy the support of some of the wealthier merchants. The first small chapel was built in 1818 and by 1833 a good-sized brick church had been completed.

The Presbyterians were badly divided too, and the little congregaton set up in 1820 by a minister of the Secessionist Church who came from Ireland was regarded by some contemporaries as including too many political radicals, an impression perhaps stimulated by the occasional presence of William Lyon Mackenzie. To make matters worse the Secessionists battled with each other. So did the other main branch of Presbyterians, housed from 1830 in St Andrew’s, which a year later came under the newly formed Synod of the Presbyterian Church of Canada in Connection with the Church of Scotland. The Baptists were later in the field, having no solid footing in York before 1829; and the Congregationalists not until 1834.

It seemed difficult for Christians within one church to love one another, and at moments inter-church relations looked better in comparison. Originally few Roman Catholics had lived in York, but the numbers went up with Irish immigration and in 1824 the first church was built, this being in part made possible by contributions from Protestants. The trustees of the church – James Baby, John Small, and the Reverend Alexander McDonell – welcomed this ‘liberality … as a certain prelude to future concord among all classes of the community.’ It was a nice, if an optimistic, thought; but concord was all too soon broken within the church itself. W. J. O’Grady, the Irish priest who came to York, entered too enthusiastically into politics as a radical, bringing dissension into the congregation. When ordered by Bishop McDonell to leave York he refused to go, and before he was finally forced out his supporters and opponents were completely at odds. McDonell, meanwhile, had found a new ally in John Elmsley who left the Church of England, of which he hadbeen an active member, to join the Roman Catholics. In a small town the conversion of such a prominent citizen caused a sensation. Elmsley’s own explanation of his action was that he had been convinced by a pamphlet on transubstantiation written by the Bishop of Strasbourg, and he thought highly enough of it to have five thousand copies printed and distributed throughout the province. It is, however, perhaps not without relevance that in 1831 Elmsley had married a Roman Catholic, the daughter of L. P. Sherwood.

One unwelcome result of immigration was the warfare between Roman Catholic and Protestant factions that broke out intermittently in York as elsewhere in Upper Canada, and in which the imported Orange Order played an active part. Previously the only fraternal society in York was that of the Freemasons and they had made only moderate progress. Simon McGillivray, their grand master for Upper Canada from 1822 to 1841, was struck by what he found when he took office, observing ‘that Masonry had not been in such hands, nor conducted in such a manner as to offer any inducement to respectable men to associate with some of those whom they might be liable to meet in lodges.’ His solution was to form a new lodge, St Andrew’s No. 1, and it did include a number of most ‘respectable men.’ Membership was not exclusively Protestant. Angus McDonell was a high officer of the order in 1800. L. P. Sherwood joined in the early thirties and John King a little later.19

The Orange Order, on the other hand, was militantly Protestant. The first recorded march in York was in 1822 when the Orangemen went to church on 12 July and heard an ‘eloquent and appropriate Discourse’ by Strachan. That was a peaceful event but not much later riots occurred in Upper Canadian towns. Francis Collins, editor of the Canadian Freeman, a Roman Catholic paper, wrote of the danger of the ‘blind folly of party spirit and religious animosity.’ Presumably that shot was aimed in one direction but responsibility for starting fights was variously attributed to one side or the other. The Orange parade on 12 July 1833 ended up in a free-for-all but the magistrates were able to restore order.20

Religious affiliation was a thread in the social and political pattern of York. Roman Catholics and dissenters were always free to conduct services and were subject to no legal disabilities in respect of voting or holding public office. The Church of England received the lion’s share of governmental funds available to the churches because it was regarded by those in authority in England and largely in Upper Canada as an integral part of the structure of a safe and sane colony. Anglicanism was strongly represented in that segment of the population of York which grew out of the little group that dominated the town in its earliest days. It was conspicuous in government, on the Bench, and on the Bar.

The preponderance of Anglicans in the community, the extent to which senior government officials belonged to that church, and the current English conception of the relations between religion and education together influenced in the 1820s and 1830s a controversy which has never flagged throughout the life of Ontario. Partly because it was the provincial capital, partly by chance, York had more than its share of the dispute over the place of the churches in education.

Schooling in Upper Canada was neither compulsory nor generally free, but neither was it in England nor in most parts of the United States. Among those who gave serious thought to the subject probably more concluded that education was for the relatively few – those who could take advantage of it – than argued that all children should attend school. Under the circumstances of the day the Common School Act of 1816, inspired by John Strachan with his Scottish belief in education, was well in the van. The act was not designed to throw all responsibility on the state but to afford financial support to common (that is, elementary) schools that already existed or might be set up by local initiative.

Such a one was started by public subscription in York, and in 1820 Thomas Appleton, a recent immigrant from Yorkshire, was appointed master. Peregrine Maitland, however, decided to introduce the Madras system under which younger children were taught by elder, and took over the Common School for that purpose. York was to have the first of what was intended to be (but never was) a series of Madras schools. One of the two branches of the Madras group, that led by Andrew Bell, was chosen and it tied the school to the Church of England. To Maitland the move would serve to offset the influence of American republican teachers (he was not the only one to be concerned about them), and he obtained public lands for the support of what came to be called the Upper Canada Central School. Charges were made that this action, including the dismissal of Appleton, was arbitrary, and objection taken to having a denominational school. In spite of these handicaps, however, the school had a healthy life. In its twenty-four years 5,514 pupils passed through it. In its first year, 1821, it enrolled ninety-five children of whom fifty-seven were boys. Of that total class only forty-three paid fees.

Since 1807 the Home District Grammar School had been located in York, the ‘Blue School’ as it was called from the colour of the exterior walls. In 1812 Strachan, who was the most influential educationalist in the history of Ontario, succeeded G. O. Stuart as master and held that position until 1823. The school taught everything from the classics to bookkeeping and its pupils included a long list of men later famous. It too, however, fell victim to the educational policy of a lieutenant governor.21

Sir John Colborne was unimpressed by the plan for King’s College, another of Strachan’s brain children. To him it was madness to go ahead with a university when there was ‘no tolerable seminary in the Province to prepare Boys for it.’ This conclusion, which may well be challenged, led him to believe that the urgent need was for an advanced secondary school which might additionally form the nucleus of a later university. The result of this train of thought was the institution with the unwieldy name of Upper Canada College and Royal Grammar School, which, as the name suggests, absorbed the District school. Indeed it occupied the old Blue School building until the new quarters on Russell Square were ready. Upper Canada could not be neatly classified as private or public. It received funds from public lands and for many years was in one way or another under the control of government, but at no time was it a standard unit in the provincial system. Technically it was undenominational, but the principal and teaching staff, with perhaps occasional exceptions, were members of the Church of England. The first principal, J. H. Harris, was a doctor of divinity of Cambridge and the masters were chosen from graduates of Oxford. Since both English universities gave degrees only to Anglicans it followed that the teachers first chosen for Upper Canada were of that persuasion. It is relevant to recall at this point that the clergy, particularly Anglicans and Roman Catholics, had made a great contribution to education in the province, both in private and state schools.

Closing the District school was a mistake since it reduced educational facilities which were in any case hardly sufficient for the town. Moreover, parents in the eastern part of York, where the old Blue School had been, protested at the distance to be covered to Russell Square. In 1836 the school was revived and a year later it had ninety to a hundred pupils. In due course of time it blossomed into the Jarvis Collegiate Institute. Of the children who did not attend any of the institutions mentioned a number went to private schools, both primary and secondary. A considerable proportion of the children went to no school; figures are not available for this period but there is no doubt that they were quite high. For all children the school year was longer than in modern times. A fortnight at Christmas, a week at Whitsun, and six weeks in the summer were the usual holidays.

In addition to the controversy over the relation of churches and schools was that over the curricula, and it centred on Upper Canada College which had a strongly classical programme. The documents in the case22 are far from enlightening since they confuse the secondary and university levels, and education with the training of mechanics and farmers. It may well be that the balance of subjects at Upper Canada College was too much based on that in the English public schools and in response to criticism it was modified. But the respective cases for vocational training and development of the mind were no more convincing to the unconverted than they have ever been.

In practice entrance to the skilled trades was through apprenticeship, and in the absence of universities much the same principle was applied to young men seeking admission to the professions. In 1831, however, the Law Society began specialized teaching at Osgoode Hall and the first medical school, a private one, was opened by Dr John Rolph in York in 1832. Organized theological colleges had to await the establishment of universities.

Illiteracy was declining (although figures would be no more than guesswork) but the rate of improvement was slowed by the fact that so many people kept their children from school. Some of them thought that education was useless except for the middle class; others claimed that fees and lack of clothes were obstacles. Others again were frank in saying that their children would be more usefully occupied at home.

The York Mechanics’ Institute, founded in 1830, was designed for adult education. It and similar institutions in other towns were modelled on those which began in Scotland in 1823 and spread throughout industrial England. The movement in the British Isles was a child of the industrial revolution and arose specifically from the desire of skilled workmen to study science, partly from general interest, partly as an aid in their work. The institutes were successful in Britain, Francis Place noting with satisfaction that he had seen ‘800–900 clean respectable-looking mechanics paying most marked attention’ to a lecture on chemistry. Started by leading citizens and subsidized by government the York institute had a useful life, but its clientele was limited by the fact that Upper Canada was not industrialized. As a result it was overweighted by the middle class. James Lesslie, a shopkeeper and associate of W. L. Mackenzie, had a different explanation of the small number of mechanics who attended. The institute, he wrote in his diary, was regarded with suspicion ‘by some of our Gentry,’ who believed that the ‘lower classes’ could be kept as slaves only so long as they were ignorant.

Public services other than education were showing improvement in varying degrees. A few streets were macadamized, yet Julia Lambert wrote that in the spring she was reluctant to go outdoors because of the pervading mud. Maintenance of law continued to rest shakily on the shoulders of part-time constables, but that the law was not without effect was noted by Mary O’Brien who observed that two murderers were convicted at the same assizes. The burning of the legislative buildings in 1824 demonstrated to the Upper Canada Gazette the necessity of having ‘a properly organized company of Fire-men’ instead of ad hoc volunteers. Two years later the York Fire Company was established and in 1831 the Hook and Ladder Company. Shortage of water, however, limited their usefulness.

Water was not only in short supply but most of it was probably contaminated. The first terrible cholera outbreak in 1832 dramatically turned public attention to the prevention and cure of disease. Under normal conditions the care of the sick was comparatively good in relation to the standards and scientific knowledge of the time. Of a number of competent doctors Christopher Widmer was perhaps the best known. An English surgeon who had served in the Peninsular War, he came to York about 1815 and there both practised and interested himself in medical education and regulations governing practice.23 His partner, Dr Peter Diehl, had studied medicine in Montreal and Edinburgh and practised in the former. The building of a general hospital was made possible by the transfer to that purpose of the surplus funds of the Loyal and Patriotic Society after provision had been made for those who suffered in the war of 1812. The substantial sum of £4,000 allowed for a brick building at the corner of King and John streets in 1820, but could not be stretched to pay for furniture or staff. When the building used by the legislature burned down in 1814 the vacant hospital was taken over for sessions until 1829 when the hospital could finally be opened with the additional aid of annual government grants.

As was the case for some decades competent dentists were rare. Mrs O’Brien wrote in 1829 that ‘I did not describe the solemn reverence with which the apothecary at York, to whom I carried my tooth, folded his hands between every ineffectual attempt to lay hold on it, looking up with a gradual inclination of his body to Anthony [her brother] for advice and sanction for the next step.’

Little had been done to improve sanitary conditions in the town. Admittedly this was a weakness not peculiar to York. In 1832 an ex-mayor of New York described that city as ‘one huge pigsty’ and even a dozen years later a newspaper capped that by charging that the streets were too foul even for the hogs that rambled over them. Not all citizens of York were complacent. Even before cholera was brought to York by immigrants, and while its relentless march was being viewed with alarm, the editor of the Canadian Freeman, Francis Collins (who was himself to die in the epidemic), was waging a campaign to clean up the town:

All the filth of the town – dead horses, dogs, cats, manure, etc. heaped up together on the ice, to drop down, in a few days, into the water which is used by almost all the inhabitants on the Bay shore … There is not a drop of good well-water about the Market-square and the people are obliged to use the Bay water however rotten. – Instead therefore of corrupting the present bad supply, we think the authorities ought rather adopt measures to supply the town from the pure fountain that springs from the Spadina and Davenport Hill, which could be done at a trifling expense.

In further articles Collins wrote of conditions within the town, which, he said, were enough to produce a plague. Remedial measures began. Lime was issued to householders; collection of garbage and sewage was initiated; box drains were installed at some points. All that was good for the future, but meanwhile cholera took its toll. The doctors did what they could but little was known of effective treatment. Circulars were distributed emphasizing the need of medical attention at the first symptom of the disease. In the absence of an isolation hospital the old District school was taken over at the instigation of a hastily organized Board of Health, but a vicious circle limited its value. Fatalities in it were high because individuals became patients only when the disease was too far advanced for the hospital to help, and reports of deaths deterred others from going there at the stage at which treatment might be of avail. It was a grim period, with cholera claiming (according to contemporary statistics) 205 deaths among civilians and twelve in the garrison.24

As a seat of government York had always been a political centre, but only after the war, when the population grew and diversified, did partisan politics play any large part. One cannot speak of party politics since parties in the modern sense did not as yet exist.

The constitution of Upper Canada was drawn up in eighteenth-century England and inevitably echoed the politico-social ideas dominant then and hardly modified before the reform bill of 1832. The monarchy, established church, and great landowners were in undisputed control. In a very real sense there was a ruling class, a fact evident in the House of Commons and throughout officialdom, the ranks of which were filled by patronage and from a very limited sector of the population. The accepted view was that those with land, education, and the tradition of public service were best qualified to carry the responsibility of government. Not all the appointees were of ancient lineage but enough were to give colour to the whole.

The British system could not be imported intact to Upper Canada, partly because the social conditions were different and partly because the latter was a colony. The head of government was not a native but a temporary visitor and one whose instructions came from overseas. In general officials were appointed by the same means and on the same principles as those in England, but with some differences. Some of them were sent from England and it proved not always possible to draw those from the cream of the crop. For local recruitment the youth of the colony and its social fabric did not present conditions comparable to those of England, but candidates did come from among a small minority of the population. An important distinction between the metropolitan power and the colony was that in the latter the elected house of the legislature was far more representative than that in Westminster.

Contemporary parallels drawn with the United States were selective and therefore misleading. In early years after the revolution Americans did not question democracy, but they did not all mean the same thing by it. Some Upper Canadians who called for a more popular control of government felt an affinity with Americans who upheld the same cause; and when that cause had a marked success with the election of Andrew Jackson in 1829 they became convinced that they had found the land of the free. The Tories – at least before that date – could have found moral support in the American ruling group who successfully maintained the principle that office holders should come from the ‘responsible’ class of society and keep their positions indefinitely. Strangely enough, however, the Upper Canadian Tories did not look at their powerful opposite numbers across the line but saw the American scene through the same spectacles as did the Reformers, so that republican and democrat were equated with radical, and radical with reformer.

The political argument in Upper Canada was essentially on the degree of popular control of legislation and administration. In spite of some claims that constitutional change was needed the results sought by all but the most extreme Reformers could be achieved through altered conventions and practices. In itself the constitution of the 1820s was essentially the same as that of modern Canada, in contrast with the reconstruction of the lower house that had to precede change in England. As the situation stood in the twenties and thirties, however, a small group had a stranglehold on government. This they secured by various means. They alone had the ear of the lieutenant governor whose power was very real. They held all the seats in the executive council and most of those in the legislative council, the upper house. And they had wide support among all classes of society in York and elsewhere.

They were called the ‘family compact,’ a phrase originally applied to an agreement on foreign policy reached between the French and Spanish Bourbons during the Seven Years’ War. Though almost meaningless as applied to Upper Canada, it was a useful form of abuse since it somehow had a sinister connotation. It was, however, misleading because it glossed over the fact that the Tories who supported this group were as representative as those who backed the Reform leaders, and because the phrase conveyed the impression of a blood relationship.

In one sense the latter did exist, for in a small place, in which ‘society’ tended to be a closed circle, marriage tied families together to such an extent that it became dangerous to gossip. John Strachan, often regarded as the epitome of the regime, had married the widow of Andrew McGill of Montreal. His relationship to members of the oligarchy arose out of the lasting influence he had over his former pupils at the Grammar Schools in Cornwall and York. Of the orginal group in York a Heward married a Robinson, an Allan a Gamble, and a Macaulay a Crookshank. In the next generation marriages took place between a Jarvis and a Powell, a Gamble and a Boulton, an Allan and a Robinson, a Macaulay and an Elmsley, a Cartwright and a Macaulay.

These are but examples and the list could be extended indefinitely. On the other hand the small size of the group regarded as eligible offers an easier explanation of office-holding than does nepotism. Some members of the oligarchy were in business as well as government, many were large landowners. Commercially enterprising, they were politically conservative. They were described by critics as self-seeking, inefficient, and even corrupt. They merited none of these accusations, but were vulnerable on the ground that they found an agreeable coincidence between public duty and private advantage. They had always benefited from land grants and patronage. By a convenient stretch of the imagination they associated opposition to themselves with disloyalty. Government, they argued, must be kept in the hands of loyal, educated, and capable men.

The opposition, lumped indiscriminately into the category of Reformers, had in common only the desire to dislodge the oligarchy. Unfriendly critics could accuse them of self-interest comparable to that of the Tories in that they wanted to seize the loaves and fishes. Some of the opposition had no need of pecuniary aid. Certainly the Baldwins – Dr William Baldwin and his more famous son, Robert – were in that class. Wealthy, somewhat austere, and welcome in the highest society, they were the most effective of the conservative reformers. Even Lieutenant Governor Maitland, who regarded all Reformers as far below the salt, admitted reluctantly that the Baldwins were gentlemen. Some other Reformers, who were substantial members of the community, would not have been accepted by the simple-minded Maitland: men like Joseph Cawthra, the shopkeeper; John Doel, the brewer; or Jesse Ketchum, the tanner.

The most notorious and vocal reformer in York was William Lyon Mackenzie. An immigrant from Scotland he succeeded as a shopkeeper in Dundas but abandoned that secure existence for the uncertainties of journalism. He began publication of the Colonial Advocate in Queenston in 1824 but later in the same year transferred it to York. Editor of a highly political paper he had no consistent political philosophy. He distrusted parties of whatever colour because he was essentially a critic and could be sure of no one who held office. His shots were aimed at the Tory oligarchy, who, he was convinced, governed in their own interest and not in that of the ‘intelligent yeomanry’ of York County, the farmers from whom he received his main support.

Moderation was seldom found in the newspapers of those days but the Advocate excelled in extremes and abuse. On a day in 1826 Mackenzie made in his paper violent personal attacks on several of the official families. It was journalism of the gutter, wholly indefensible and unrelated to public questions. Some of the young men whose relations were maligned marched to the newspaper office, did as much damage as they could, and threw the type into the bay. It was a stupid act as Robert Stanton, a Tory journalist, was quick to point out in a letter to his friend, John Macaulay:

Entre nous I fear the zeal of some of our friends has been rather intemperately expressed in the destruction of some of Mackenzie’s printing apparatus … The measure was too strong I fear and may be the means of affording the blackguard a sort of triumph at the expense of respectability – he had gone and we heard of him from persons who saw him at Youngstown, and I have no doubt we should have been entirely rid of him and very soon of his paper too … the fellow will now I think return to prosecute the parties.25

He did indeed, and was awarded substantial damages which enabled him to resuscitate a dying paper. That is one interest of the episode, but it also illustrates the persistence of the oligarchy and their friends in putting themselves in the wrong. Magistrates were, with good reason, accused of being partisans in that they did not quell a disturbance. The stupidity of the young was excelled only by that of their elders in ostentatiously collecting money to recompense law breakers who might have learned sense if their pockets had been emptied. All good grist for Mackenzie’s mill – a martyr now, and richer.