The end of an era

A description of Toronto as it was in the generation before the second world war might still bear the title of Henry Scadding’s classic, Toronto of Old; for, large as it had become, the city had still much of the ancient character that was to be diluted and modified in postwar years.

Between 1905 and 1939 the city grew from about seventeen square miles to thirty-five. The change was due to a series of annexations of which the principal were North Rosedale (1906), Deer Park (1908), East Toronto (1908), West Toronto (1909), Midway, well beyond the Don (1909), Dovercourt and Earlscourt (1910), the very large North Toronto (1912), and Moore Park (1912). By the time of the first war Toronto had reached approximately its present boundaries, with the exceptions of Forest Hill and Swansea, which were added by the provincial government in 1967.

Within this expanding territory the city was sorting itself into quarters: wholesale trade, retail trade, finance, manufacturing, and the different classes of residential districts. Here and there were individual houses beyond the limits and further out the suburbs, most of which were still small. Already at the beginning of the century Toronto was a substantial city, but its new-found prosperity nearly went up in flames.

Fire, caused by defective wiring, broke out on the evening of 19 April 1904 in E. and S. Currie’s neckware factory on the north side of Wellington Street west of Bay. Chief Thompson entered the building with a small detachment, was trapped, and in escaping injured his leg and was taken to hospital. The fire was already fierce and out of control. Fanned by a gale from the northwest it swept down Bay Street, jumped across Front Street at about eleven o’clock, and spread westward at the same time. The Toronto Fire Department was putting up a good fight, but the water pressure was not good and men and equipment were insufficient to deal with this over-whelming march of flames. Appeals for help brought reinforcements from Hamilton, Buffalo, London, and Peterborough.

It was a frightening scene, with sparks and debris blowing wildly for hundreds of yards. Dynamiting was tried but to little avail as the wind blew fire across the spaces thus made. Boats pulled out of the docks into the bay while citizens crowded downtown to see the spectacle and children were held up to distant windows to watch the glow. A few companies were able to rescue their records and other valuables and in several cases employees entered the battle with such hoses as were in their buildings and often strove to good effect. In the Queen’s Hotel, close to the centre of the fire area, guests and staff draped wet blankets over the window frames and kept dousing them as the hot wind dried everything. Several times the roof caught fire but watchers put it out. ‘Acts of daring and strategy as any feat of arms’ was the way in which the Globe described the stands made at the Customs House and the Bank of Montreal. Up Bay Street the Telegram building was saved, and with that the prospect of destruction of more vulnerable buildings was averted. For a time it must have seemed that it would be impossible to stop a fire so widespread and so violent, and it was a tribute to the local fire department and its allies that the danger was over by the morning.

‘Standing at the corner of Front and Bay Streets,’ wrote the Globe reporter early on the next day, ‘one begins to realize the extent of the awful destruction that has been wrought, on every hand are ruins almost as far as one can see. Within the whole burned area there is not a single wall intact.’ Fourteen acres with eighty-six factories and warehouses, much of the commercial strength of Toronto, were devastated. Insurance experts estimated the loss at $13 million and five thousand employees were thrown out of work. The companies concerned were enterprising in making temporary arrangements, and before the embers were cold architects were at work on plans for new buildings. But for decades afterwards blocks of ruins along Front Street reminded Toronto of its great fire.

Destructive as the fire was it never got beyond one area, thanks to the efforts of the firemen and the direction of the wind. Part of the main business district escaped as did all the residential ones. At the time 226,365 people lived in Toronto. Ten years later the number had risen to 470,151, and at the time of the second war to 649,123. The last was not far below the point at which the population was stabilized by the metro system and by withdrawals beyond the city limits. Toronto had more immigrants than any other Canadian city, and in 1931 they made up more than a third of the whole. For the most part, however, the newcomers were – as in the past – from the British Isles, so that the population was predominantly British. Migration into the province from Quebec became considerable, but most of it was to the northeast. The thin end of the European wedge was beginning to show in the census of 1941. Germans, Italians, Poles, Scandinavians, and Ukrainians were all to be found in Toronto but as yet in numbers too small to affect the balance.

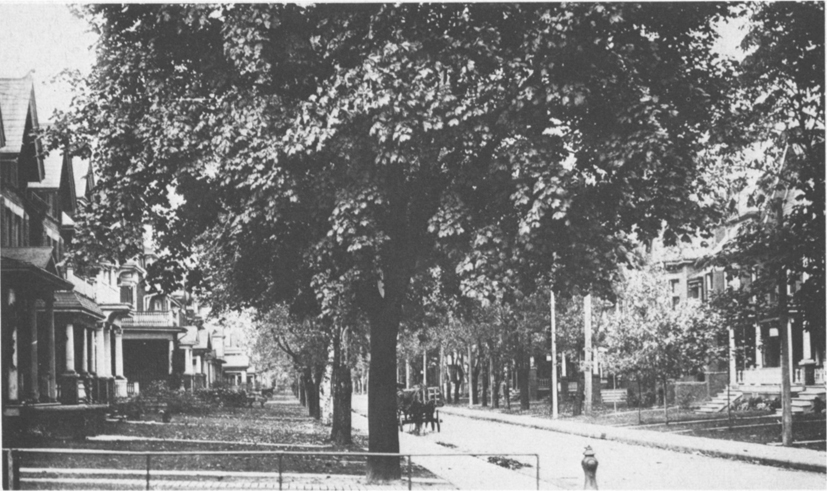

Macdonell Avenue, Parkdale, 1917, characteristic of middle-income districts

Some of the wealthy and comparatively wealthy continued to live on such established streets as Beverley, the lower part of St George, and Jarvis. North of that the Annex was filling up with numerous semi-detached houses, solid and capacious but lacking in style, and larger houses interspersed among them. On the hill, above and below St Clair Avenue, neighbours were remote at the beginning of the century but building continued in all that part. By the twenties apartment houses were still not common but numerous enough to constitute a recognized category of dwellings.

Little headway was made in providing houses for low-income families. One stage of the problem has been described in some detail in the previous chapter. Under the authority of a provincial act of 1913 the Toronto Housing Company was incorporated and the city guaranteed its bonds; The company built and operated Riverdale Courts on Bain Avenue (east of Broadview) and the Spruce Courts on Spruce Street. They contained cottage flats of three to six rooms with separate entrances and together could accommodate 334 families. The rents were $23 to $40.

In 1920 the Toronto Housing Commission was established by statute and was authorized to build houses for working men of moderate means. The commission, made up first of private citizens and later of municipal officials, erected 236 houses in the eastern and western parts of the city, and sold them on condition of monthly payments covering principal and interest. In the depression years the owners found difficulty in meeting their commitments.

In 1934, at the suggestion of the lieutenant governor, H. A. Bruce, the city appointed a commission, not to build houses, but to examine the housing that existed in poorer districts. Its findings on slum areas make grim reading. Of 1,332 dwellings covered in the survey 96 per cent fell below the committee’s standard of amenities and 75 per cent below its standard of health.1

Early in the war, Board of Control appointed two men to examine housing in general. They reported ‘the most acute housing situation in half a century. More than three thousand dwelling units were needed. They gave as causes of the shortage the city’s failure to act on any housing plan in the years 1922-42, decline in building, increase of employment in Toronto, higher earnings which enabled some families to have separate dwellings, and movement of suburbanites into the city because of gasoline rationing.2

Within the average house radical changes took place in the first thirty years of the twentieth century. Already at the beginning of that period central heating by coal burning furnaces was fairly general. Hot air, steam, and hot water systems were all used. Indoor plumbing, too, had been accepted by even the most conservative. Since the city sewers did not always keep up with the spread of houses, septic tanks had sometimes to be installed. Electricity was slower to be generally employed for lighting but then gas already gave satisfactory results. Mechanization was not rapid, but neither was it as essential when domestic servants were available. Electric clothes washers were not on the market until the early twenties, electric sewing machines before the middle, or vacuum cleaners before the end.

Many houses had furniture of an older and better period, but if additions were needed or new houses required to be equipped it would ordinarily be necessary to draw on what was made at the time. Through the first two decades of the century anything not especially designed by an enlightened few was of unequalled ugliness. The contorted styles of the late Victorian era faded out after the first war, but unhappily the pieces were solidly made and lasted all too long. Complicated patterns and a general impression of heaviness were evident in curtains and blinds of the same years. Comfort was not ignored but aestheticism had no priority.3

The churches continued to play an important part in the life of the community, not only because the average family attended religious services on Sunday, but because the churches were active in organizing social activities and in welfare work. According to the census of 1921 the Church of England still had a substantial lead, with the Presbyterians next, then the Methodists, and the Roman Catholics somewhat fewer. The Jewish population of Toronto had increased considerably. The exact numbers of adherents of any church are not known, but the important fact is that the churches were filled and new ones were built as the city grew. Few contemporary records can be found of the range of activities of any of the churches, perhaps because they were taken as a matter of course. One interesting diary is that of Mrs Mary Robertson, wife of a Scottish beadle at St Andrew’s Presbyterian Church on King Street, for she jotted down her ‘experiences and anecdotes.’ In 1917 the church was busy with war work. Women came to spend all day at such tasks. ‘How these women work, and how they gabbled.’ In 1919 the church’s finances needed to be restored after expenditures on soldiers’ comforts, and to that end sixty men spent five evenings planning a campaign to raise money.

January of 1920 was bitterly cold and many calls came in from those who were without food or fuel. Members of the congregation, Mrs Robertson recorded, were marvellously kind in meeting needs. In December Christmas tree parties were held for the children, Mrs Robertson filling two hundred bags with candy for the occasion. Then came receptions for new members of the church, dancing classes for the children, and Irish banquets – complete with jigs – for the boys of the Sunday school. Supper parties, too, were organized for children from various missions.4

Mrs Robertson was violently opposed to church union, being in step with the minister, Stuart Parker, also a Scot, who was actively in opposition to the proposed merger of the Presbyterians with the Methodists and the Congregationalists. In the case of the Presbyterians the decision was to be made by individual congregations. The vote at St Andrew’s – according to the diarist – showed only one woman in favour of union and Mrs Robertson declared that she was really a Methodist. St Andrew’s and a number of other Presbyterian churches rejected the union proposals and became known as ‘continuing Presbyterians,’ but the United Church was none the less founded in 1925.

Public schools, separate schools, high schools, and private schools together formed a complete pattern. For pupils, and more especially for adults, the library system was adequate. The reference library at the corner of College and St George streets, the central circulating library on Adelaide Street, the municipal reference library in the city hall, and twelve branch libraries scattered throughout the city were ample for the reading public. Books issued for home reading in 1922 amounted to 1,854,579.

After years of stress and uncertainty the University of Toronto was settling down to solid growth under the wise guidance of two successive presidents. Sir Robert Falconer (1907-32), who had come from Pine Hill College in Halifax, had been a Presbyterian minister and a scholar whose own attainments led him to encourage advanced studies in the university. He was succeeded by H. J. Cody who as rector had filled the great church of St Paul’s, was minister of education in 1918, and member of the board of governors of the university since 1917. He became president in 1932 and held that office until elected chancellor in 1944. Over a span of nearly forty years the university became considerably larger and known for advanced studies in several fields. To take a few examples: J. C. (later Sir John) McLennan was a distinguished physicist whose researches included the magnetic detection of submarines. Dr (later Sir) Frederick Banting and Dr Charles Best discovered insulin. H. A. Innis, economist and philosopher, inspired a whole new school of scholars in their approaches to economics, history, and communications. E. J. Pratt became recognized as an accomplished poet from the time of his first publication in 1923. The smaller McMaster University moved from the shadow of its large neighbour in 1930 to develop rapidly in Hamilton.

Mendelssohn Choir, 1911, conductor Augustus Vogt, performance of ‘Children’s Crusade’ in Massey Hall

An important addition to education and culture in Toronto was the Royal Ontario Museum. Formally opened in 1914 it had for several years been in the planning stage with some gathered works of art. Early in the century C. T. Currelly, who became the museum’s first director, had been sending material from the middle east to Victoria College, but consultation led to the conclusion that it would be best to establish one museum for the university as a whole. Sir Edmund Walker, chairman of the board of governors of the University of Toronto, had long advocated museums, and he now took a leading part in organizing the foundation by the university and the provincial government of a museum that quickly attained international rank.5

In the field of communications it was a question whether the spread of radio broadcasting would overshadow the press. Receiving sets were coming to be the rule rather than the exception in Toronto by the late thirties. As it proved, the newspapers survived the rivalry but they themselves were going through changes. A relatively large number of dailies, each expressing the personality of the editor, were being caught up in the trend toward large-scale business. Fewer papers with larger circulation took over. They might be politically partisan but were no longer dependent on the financial support of political parties and were more commonly associated with the publisher (often the owner) than with the editor. In 1936 the Globe, long since dissociated from the Brown family, was bought by a businessman, George McCullagh. He, with financial support from a mining man, W. H. Wright, also bought the Mail and Empire. The two were then merged under the name of Globe and Mail, a paper professedly independent politically. Thus Toronto readers were left with one morning and two evening newspapers.

Toronto was rich in musical performance if not in composition. Families and groups of friends, amateur and professional, continued to enjoy evenings of music in their houses. Old and new choruses flourished. A. S. Vogt disbanded the Mendelssohn Choir for three years, reconstituting it in 1900 on a different basis. In 1902 the choir began its joint concerts with American orchestras, the first being the Pittsburgh Symphony under Victor Herbert. Combined concerts were given in both Canada and the United States, notably of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony in New York in 1907 and of Brahms’ Requiem in Cleveland in 1910. In 1917 Vogt was succeeded by H. A. Fricker, an English organist, and in 1942 by the Canadian organist, E. C. MacMillan. Albert Ham, organist of St James’ Cathedral, directed the National Chorus from 1903, and Edward Broome the Oratorio Society. Healey Willan, who came to Toronto in 1913, was still another of the distinguished organists of Toronto. Before and after his arrival he composed church music, symphonies, radio operas, and a piano concerto.

Most of the leading musicians in Toronto had come from the United Kingdom, but there were European influences as well. Vogt was born in Ontario, the son of a German émigré of 1848, and himself returned to Germany to study. The three Hambourg brothers – Mark, Boris, and Jan – came to Toronto from Russia in 1910, already having achieved fame as an instrumental trio. They founded the Hambourg Conservatory of Music, and Boris was the cellist of the Hart House Quartet when that was founded in 1924. The Conservatory String Quartet, active in the same period, included another distinguished cellist, Leo Smith, who was professor of music at the University of Toronto.

Individual artists, including the incomparable Caruso, other leading singers and instrumentalists, and a number of orchestras performed in Toronto. A local symphony orchestra was founded in 1908, one with seventy to eighty professional players and with Frank Welsman as conductor. Suspended during the war, it was revived in another form in 1924. Luigi von Kunits was the conductor. Only twilight concerts were given, that making it possible to enlist musicians who in the evening played in theatres. The third form of the orchestra began in 1932. Evening concerts were brought back, with Ernest MacMillan as conductor. The Promenade Symphony Orchestra, under Reginald Stewart, gave summer concerts from 1934, providing pleasure for the audiences and employment for professional players.6

For a dozen or more years of the new century the professional theatre, free of the rivalry of motion pictures, flourished as before. Many excellent touring companies came throughout the season to the Grand Opera House, the Princess, and the Royal Alexandra. The last, too, had for several years a repertory company during the summer. A leading lady who came for several summers, Percy Haswell, was a particular favourite. Amateur theatricals gained increased vigour and support, some of the companies competing in the Dominion Drama Festival which began in 1933.

One of the most interesting and least visited corners in Toronto was the Studio Building in a Rosedale ravine where three of the new Group of Seven painters – J. E. H. MacDonald, A. Y. Jackson, and Lawren Harris – had their winter quarters. Tom Thomson refused such luxury so an old shack behind the building was partially restored, and in it he impatiently awaited spring and Algonquin Park. The Group’s subjects were peculiarly but not typically Canadian, since they were for the most part scenes in the pre-Cambrian shield with hardly a glance at the softer lands of the south in the style which had appealed to the late nineteenth-century landscape painters. At first the new style of painting was regarded as strange, almost revolutionary, but in time its character was appreciated, and the wealthy began to look doubtfully at the Dutch pictures which almost invariably adorned their walls.7

In any late summer pictures could be seen too at the Exhibition, in company, of course, with innumerable other things. The popularity of the fair was increasing, both for residents and visitors. It was estimated that the latter annually brought $5 million to the city. Attendance first edged past the million mark in 1928 but fell again under the weight of the depression. Toronto has never been famous for its parks but the exhibition grounds had been kept free. The official list of parks and playgrounds in 1928 gave a total of 1,662.51 acres. As many as eighty-three baseball diamonds showed how that game had gained favour at the expense of lacrosse, which was allotted only five. Similarly 261 tennis courts indicate another conquest. Several cricket clubs played on every Saturday afternoon of the season. For skating there were sixty-two rinks and for hockey sixty. Some, though never enough, playgrounds were open for children. A small zoo at Riverdale Park, exhibits of flowers, and the pleasant spaces of the island were all spread out for the people generally. In 1931 the Maple Leaf Gardens were ready for the hockey team of that name. It was at this time that the great amateur hockey teams and football teams of the twenties were being eclipsed by professional ones.

In the variegated life of a city the ideal is a partnership between public and government in which, according to subject, one takes the lead, helped as need be by the other. At the same time it is necessary for the citizens to participate in the process of government, if only in elections, supporting such improvements as they deem appropriate. Without reaching perfection this kind of relationship did exist to advantage in the first thirty years of the century.

The form of municipal government was little altered, nor was there, apparently, any appreciable demand that it should be. On the other hand the provincial agencies concerned with municipal affairs were reconstructed in such ways as to place greater authority in the hands of specialized bodies. The Ontario Railway and Municipal Board was created by statute in 1906 and given powers in certain fields, particularly the financial, and of course over railways. In 1917 the Bureau of Municipal Affairs was set up to deal with public utilities. In 1932 the Railway and Municipal Board was renamed the Ontario Municipal Board, the Bureau of Municipal Affairs placed under it, and its powers widened then and later. A Department of Municipal Affairs began in 1935, designed to have a general oversight of municipal questions.8

The system of taxation went through some changes. In 1904 the personal property tax was, by provincial statute, replaced with a business tax, which was on premises used for carrying out any trade or profession. That delighted the Board of Trade which had described the old method as ‘inequitable and inquisitorial.’ For a time a municipal income tax was imposed but that too was abolished in 1936. The tax on real property remained the principal source of revenue. For example, in 1937 it was 88 per cent of the total.9

Expenditure of public funds was obviously a question on which the public might properly comment. Estimates before the depression of 1929 showed as major items debt charges, schools, police, and a variety of public services.10 The last particularly affected the daily life of citizens. The humble but necessary sewer had become almost general but disposal was not satisfactory (or ever was to be). The city works produced an adequate amount of water, but the public did not all share official confidence in its purity. The fire department had been reorganized, although, as will be seen, it was still the object of criticism. For street lighting gas was used to some extent until 1911 but electricity was steadily taking its place.

Electricity for both light and power was introduced, as has earlier been noted, in the late nineteenth century. Technical difficulties, however, limited its usefulness. The arc lamp was too bright for most interior purposes and, being wired in series, all such lamps had to be on or off at the same time. Originally all electricity was generated by steam engines in local plants and passed short distances, by direct current and in unchanged voltage, to the lights. Three innovations gave to electricity its more general usefulness. Generated by water power, it could be transmitted in alternating current and at a high voltage over considerable distances, with the current then reduced to a safer level by means of transformers, and fed into incandescent lamps.

It was, then, possible to convey electricity from the Niagara rapids to Toronto. The Toronto group headed by Frederic Nicholls, Henry Pellatt, and William Mackenzie absorbed the Niagara Power Company – the transmission agency – as a feeder for the Toronto Electric Light Company and the Toronto Street Railway. In these first years of the century, however, municipalities in Ontario were demanding an investigation of the possibility of public suppliers which, they thought, could charge lower rates. A provincial act of 1903 authorized municipally owned works on condition that an advisory commission first explore the field. Such a one was established in the same year with Adam Beck as a member. It did prepare a report recommending that municipalities proceed with a joint programme, but before that was finished a Conservative government came into office, in 1905, and followed a modified course. Beck became a member of Whitney’s cabinet and chairman of a second commission of inquiry.

Fashion parade, 12 March 1919; one of the early Eaton fashion shows during the company’s fiftieth year celebrations, auditorium of the Furniture Building (later the Annex)

Meanwhile cities and towns continued their cry for cheap power, dramatizing it by a parade of fifteen hundred delegates to the Toronto city hall and the parliament buildings. In the same year, 1906, the legislature passed an act ‘to provide for the transmission of power to municipalities’ and for a Hydro-Electric Power Commission of Ontario. Toronto responded by signing with the commission a contract for the purchase of power, brought from Niagara, to be distributed by a civic agency created for that purpose, the Toronto Hydro-Electric Commission. By 1911 rates had been cut almost in half. Until 1920, however, the Toronto Electric Light Company continued to operate, in competition with the municipal body. The former had the advantage of using 60-cycle current, whereas the Ontario Hydro had ill-advisedly selected the flickering 25-cycle (which later they abandoned).11

Up to a quarter-century ago citizens of Toronto charged, with some reason, that their city was being allowed to grow in a haphazard way without thought for the future, and indeed without solutions to pressing current problems. It was sprawling across a widening area, so it seemed to them, without proper attention to health, appearance, or convenience. Streets were not broadened or cut through before expensive buildings stood in the way, and highways leading out of the city were wholly inadequate. A maze of overhead wires defaced the streets. No substantial steps were taken to eliminate slums. Land that could have been reserved for parks was allowed to be used for other purposes. The waterfront was shut off by railway tracks, commercial buildings, and smoke.

And yet if the city had been judged by the quantity and quality of paper plans it would have been seen as one of the most advanced of its time. A whole library of studies, all containing excellent recommendations, accumulated. Planning began when the Town of York was first laid out. Most of the bad and few of the good features survived. For the first fifty years of the city’s existence nothing resembling modern plans were made, but the local government did conduct a series of ad hoc struggles over the preservation of the waterfront, the use of the Garrison Reserve, and those parks that did come its way.

At the turn of the century, however, the initiative of a group of public-spirited citizens marked the beginning of a period of hard thinking about the future of the city. For a time the effort was principally unofficial but developed into that alliance of public and government that has been suggested as a sign of health in an urban community. The Toronto Guild of Civic Art was organized in 1897 by a number of men who sought to promote the improvement of the city in both its artistic and utilitarian sides. By 1908 it had nearly four hundred members and an able committee. At the time of its first report, in 1909, the advent of the motor car, increase in population, and swelling boundaries were all signs, as the Guild remarked, that the city was at the parting of the ways. It was, indeed, to remain stuck at the parting of the ways for a long time, oblivious of the excellent suggestions for arterial roads cut diagonally, wider streets, and more parks.12

The Guild made further reports at intervals, but in the first one proposed the establishment of a body to prepare a plan for the improvement of the city. Acting quickly, the city council set up a Civic Improvement Committee in the same year. The new body was almost inactive for two years, but after being reorganized began to face its job. Membership included the mayor, three controllers, seven aldermen, and a number of well-known citizens, including a useful overlap with the Guild. Sir William Meredith, formerly leader of the provincial Conservative party and now chief justice, was elected chairman. Later in 1911 a report was issued that covered a wide field. The emphasis was again on transportation. From a proposed civic centre, the boundaries of which were defined, diagonal roads should be cut northeast and northwest. A long list of existing streets should be widened and connected wherever there were breaks. A bridge over the Don Valley was needed, to be connected with Bloor Street (which stopped at Sherbourne) by a diagonal from the corner of Howard and Parliament streets.

Particular attention was drawn to transportation to, and within, districts then outside the city. The ‘piecemeal and haphazard development of the suburbs’ left an ‘inconvenient maze of uncoordinated streets, which, by the greatest stretch of the imagination cannot be called thoroughfares.’ Bearing in mind this deplorable situation in relation to the future of the city, the report called for the creation by the provincial legislature of a metropolitan district and ‘a competent body clothed with the necessary powers for carrying out a broad, sane and comprehensive scheme of Civic Improvement.’ Specifically on transportation the report asked for rapid transit to the suburbs, which, they said, would mean subways.13

In making that study the committee had the advantage of an analysis of public transport prepared by two American experts who were called in by the municipal government. The resultant report was based on two convictions. One was that ‘the growth and standing of cities are enormously dependent upon transit facilities,’ and the other that municipal operation was ‘usually incompetent and wasteful and unsatisfactory to the public.’ They considered that within the city limits the street car service was on the whole adequate, but that the same was not true of outlying districts. Like the contemporary planning groups they recommended diagonal highways, but were also convinced that shallow-depth subways were needed, starting with a line from south to north.14 In 1911 city engineers prepared plans for a subway, but when the proposal was put before the electors it was rejected. Another consulting engineer advised a subway in 1912.

From that time the idea of subways remained for long quiescent, attention being directed to street railways and radials. For the latter a sweeping scheme of lines was being advocated by Adam Beck.15 It was with these discussions in mind that in 1915 T. L. Church, the colourful and perennial mayor, asked for advice from a technical group consisting of the city’s commissioner of works, the chief engineer of the Ontario Hydro, and the chief engineer of the Toronto Harbour Commission. Two recommendations were made: that the city take over the street railway on the expiry of the company’s franchise, and that a new transportation commission be established including representatives of the bodies from which the members of the group came. Such a commission should be vested ‘with all necessary power to plan, control and direct all transportation and terminal facilities of every kind whatsoever (exclusive of existing steam railways).’16

Since 1911 the city had been operating street cars as supplementary to those of the Toronto Railway Company, which had refused to extend its one-fare tickets beyond the city limits of 1891. These lines, known collectively as Toronto Civic Railways, served the outlying districts of the expanded city, but each of them collected a separate fare. By 1920 there were nine separate transit systems, an inconvenient and expensive situation for anyone travelling in the outer areas. Since the company’s franchise terminated in 1921 the future of the railway was put to public vote, the electors deciding to take it over so that it, combined with existing public lines, would form a single street railway, publicly owned and operated.

The Toronto Transportation Commission was ready to assume responsibility in 1921, and immediately began to implement a programme of consolidation and modernization. Better rolling stock was procured and the more important change to a single ticket for the whole system put into effect by 1923. Buses were introduced as supplementary to street cars, the first, appearing in 1921, being double-deckers with solid tires on the London or New York model.17

Since the city was so rapidly absorbing the immediate suburbs the system of transportation that had thus been evolved applied to a large area. Beyond those widened limits density of population was low and it was not rising rapidly. In 1921 the Township of Etobicoke had only 10,445 people, that of Scarborough 11,746, and the three Yorks together 57,448. Yet a need existed for travel to these and other townships and the means of doing so left a good deal to be desired. Electric radials seemed for a time to be the solution, but they necessarily left many routes uncovered and were being overshadowed by the automobile, which did not need to follow set tracks. It was true that roads were still inadequate, but from 1914 the province undertook to build better ones radiating from Toronto. The Toronto and York Highway Commission and the Toronto and Hamilton Highway Commission were two bodies set up for this purpose. The cost of works undertaken by either would be shared with the city. The concrete highway built to Hamilton might nowadays be mistaken for a wide sidewalk, but no great trucks spread themselves across it, and to the reluctant mudlarks of fifty years ago it was a glimpse of heaven.

Planning continued along much the same lines. The Civic Guild described how College Street should be widened,18 and later analysed the difficulties of the Moore Park area;19 but the next broad approach was left to a new body, the Advisory City Planning Commission, consisting of eight men appointed by the city council in 1928. Its first report concentrated on widening streets, including Richmond, York, and Queen; extending University Avenue southward; opening a new diagonal boulevard to the exhibition grounds; and running a new street between Bay and York.20 The permanent officials to whom the report was referred recommended the adoption of proposals for widening certain of the streets.21 In 1930 the Civic Guild made further suggestions concerning streets.22

Such is the tale of city planning, prewar style. It was limited in range and down to earth, but it did offer sensible solutions to a number of pressing problems. Here and there throughout the pages of the many documents were imaginative suggestions that later bore fruit, but the immediate results were small. A little widening was done, and a few streets, like University Avenue, extended. Government and public were cautious and the city was little altered as a result of so much mental effort. Finally the depression tied purse strings, and Toronto remained essentially as it had been.

Another type of private intervention had to do with the administration of the city generally and particularly in fields other than traffic. In 1913 an organization of citizens first known as the City Survey Committee commissioned the Bureau of Municipal Research in New York to examine the treasury, assessment, works, fire, and property departments. The report thinly concealed an iron hand in a velvet glove.23 ‘Administrative defects,’ the director wrote, ‘are primarily those of methods and not of men.’ It was a pleasant gesture to officials who had co-operated, but followed by a long list of mistaken procedures and in some cases of inefficiency. In the treasury department accounting was well done but budgetary methods had many faults. Departmental estimates provided inadequate information and a civil list was needed. That revenue from the street railway should be used to reduce taxation while repairs to the railway track pavements came out of debenture issues was beyond understanding. Such are examples taken from seventy-five pages of criticism.

In writing of the assessment department it was pointed out that while density of population in Toronto was exceptionally high and housing conditions poor, owners of property had not been encouraged by their assessment to improve their houses. Insufficient information was made public, although ‘publicity and publicity alone will insure equity and fair play in making assessments.’ The department of works was already being reorganized, but in any case the bureau made twenty-nine suggestions for change.

The fire department was the object of the most severe censure. Organization, training, size, and efficiency were all below par. Preventive rules were being ignored in theatres and the department had done nothing to enforce the provisions of the by-law. Indeed the situation was considered to be so serious that the bureau had made an emergency report to the mayor. In the property department the conspicuous weakness was the incongruous list of duties for which it was responsible. Several of the functions should be transferred to more relevant departments.

The City Survey Committee, perhaps impressed by the value of the report which it had inspired, reorganized under the name of the Toronto Bureau of Municipal Research. It described itself as

a permanent citizens’ organization supported entirely by private subscriptions. Its chief aim is to keep alive citizen interest in the citizens’ business during the 365 days of each year between elections. It strives to attain this end by discovering all the meaningful facts concerning city government and keeping the citizens continuously informed as to those facts by concentrated publicity, without indulging in personalities or partisan politics. Its belief is that an untiring pursuit of this end by these means will, within five years, result in large savings and more efficient city services.24

The members of the Toronto Bureau, drawn in the main from the business world, were an able group, supported financially by a long and imposing list of commercial, financial, and legal firms. The bureau issued bulletins on particular aspects of city business and an annual report, the first of which was dated June 1915. The bureau, like that of New York, emphasized co-operation with city officials, and one of its early activities was to have a series of conferences on aspects of municipal government. It examined many subjects, for example in 1920-1 it surveyed public and separate schools, motor buses, telephones, and the budget. Like the planning groups it marked an important stage in acceptance of responsibility by private citizens for the well-being of their city.

At midnight on 5 to 6 March 1934 rockets and bombs sent up on the island, a giant bonfire on the western sandbar, and the strokes of the bell in the tower of the city hall proclaimed that Toronto was a hundred years old as a city. Within the Coliseum in the exhibition grounds eleven thousand people took part in a watch-night service. All the celebrities were there: governor general and lieutenant governor, prime minister and leader of the opposition, premier of Ontario, military, religious, and academic leaders. As the new day and the city’s new century began the choir sang a Te Deum and the national anthem.

In the middle of April a series of concerts were given: by the Toronto Symphony Orchestra, the Hart House String Quartet, pupils of the public and secondary schools, the American Bandmasters’ Association, and the Mendelssohn Choir. The twenty-fourth of May was chosen as the beginning of outdoor festivities since, as the official programme remarked, Victoria Day had long been a public holiday dear to the heart of Toronto.25 In spite of this British beginning the one new note in the proceedings was then struck – a parade of ‘national groups’ in native costumes. Then came the veterans of wars, and after them floats recalling the history of York-Toronto. The objective of the procession was Fort York, to be reopened after restoration. On the following Sunday games were arranged in all the parks, again with a bow to the allegedly international character of Toronto’s population. It was well meant but not descriptive.

Toronto, as the programme and the speakers did not fail to point out, had grown greatly in territory and population. It had become a modern city with the amenities that pertained to that status. It was as prosperous as the depression allowed, if without the great wealth of later years. People and government had given much thought to the steps needed in relation to future growth. Yet Toronto still retained much of its traditional character. Even physically it inclined to the past, since the imagination of the planners had done little more that build a bank of ideas from which to draw in the future. The sharp edge of religious intolerance had been blunted by time but the Puritan Sunday died hard. Visitors complained that on that day nothing was open except the churches. On the whole, too, they still thought it to be dull and provincial. The residents were aware of their reputation. Some of them thought it nonsense. Others remarked lightly that Toronto was an overgrown village, uninteresting, perhaps, to visit, but a pleasant place in which to live.

In politics Toronto was rated as supporting the Conservative party and generally suspicious of anything unorthodox. Such a state of mind has sometimes been attributed to British ancestry, an argument that is invalid since Britain has always been a refuge of new ideas. Indeed, the creed of the principal socialist groups in Toronto was imported from England, as was the experience of organized labour in politics. While it was not necessary to be conservative to disapprove of the philosophy of Russian communism, a predominantly conservative community was particularly sensitive to any sign of an attempt to spread into Canada a doctrine designed to overthrow the political, social, and religious order. The general strike in Winnipeg in 1919 was widely believed to have been organized by imported communist agitators, and as such to be a warning of danger.

To some of those who suffered most from the depression which began in 1929, or to those who studied its effects, it seemed that an order of society which could collapse so badly and produce so much misery must be defective. Such reflections did not by any means necessarily lead to adherence to any particular alternative, but did bring serious discontent and criticism of the existing regime. The communists in Canada hoped to channel such thinking into the stream of their argument that capitalism could bring only inequity and disaster for the masses. Unrest in labour camps organized for the unemployed seemed to some observers to be an indication that communists were exploiting the dissatisfaction of the day. In reply to those who claimed that communists in Canada were too few to constitute any threat the reply could be made that the Bolshevik revolution had been the work of a handful of Russians and that the Communist party in the Soviet Union was a small part of the population.

The question that came before the people of Toronto, as they saw it, was whether to tolerate the public exposition of communist ideas. For a year or more before the depression began, an active controversy had raged over this point, and it gained momentum from the conditions that followed the autumn of 1929. By a strange anomaly the decision was made on behalf of the city not by its elected representatives or by an expression of public opinion but by a body ill-designed for that purpose, the Board of Police Commissioners. By a provincial statute of 1858 such a board was to be established in each city and was to be made up of the mayor, recorder, and police magistrate. The municipal council was, then, represented only by the mayor who, apparently by convention, was elected as chairman. The other two members were provincial appointees. That the board should be independent of council was a main principle followed in the act, the intention being that by this means the police force would be insulated from political pressure and patronage. Decisions of the board were to be by majority vote.

No substantial amendments were subsequently made to the act of 1858. The Consolidated Municipal Act of 1922 (12 and 13 Geo. v, c. 72) substituted a county court judge for the recorder, adding that if there were two or more judges the lieutenant-governor-in-council would name one of them to the board. Similarly an act of 1929 (19 Geo. v, c. 58) provided that if more than one magistrate held office the provincial government would assign one of them. In 1928 the Toronto board consisted of the mayor, Samuel McBride; a county judge, M. Morson; and a police magistrate, Emerson Coatsworth. In 1930 only the mayor changed when B. S. Wemp took office. In 1931 W. J. Stewart became mayor and Morson retired. The chief constable, D. C. Draper, a former army officer with no police experience, was for a time secretary of the board and later attended only in an advisory capacity. The newspapers of those years spoke of a wide split within the board, noting that the mayor was always in a minority of one on questions concerning allegedly communist meetings, and that the course followed by the board, and therefore by the police, was laid down by Coatsworth and Draper, supported by the county judge.

The responsibility of the police force, under direction of the commissioners, was to enforce existing laws and by-laws. It did not have, nor was it intended to have, competence in judging political or social doctrines. The course of events, however, suggests that the distinction between these two functions was blurred. The simple purpose followed by the board was to prevent communists from conducting any propaganda. Two difficulties seem not to have deterred the majority. One was the definition of ‘communist.’ Members of the party, if they could be identified, were obvious; but there was a tendency – encouraged by the communists themselves – to confuse communism with other forms of socialism or indeed with anything judged to be radical. The second difficulty was that the legal foundation for police action was shaky.

The city council was deeply concerned with the situation that developed. Its sole representative on the board of commissioners, the mayor, was helpless and frustrated. Although the board had been deliberately designed as a non-political body it had in fact become intensely political, and was a law unto itself. Members of the council attempted to take the only remedial action at their disposal, to induce the provincial government and legislature to modify the composition and powers of the board. In November 1930 council agreed that there be referred to its committee on legislation a proposal that the board be in the future composed of the mayor, the senior county judge, and a third man to be agreed upon by those two.

After examining the matter the committee sought and obtained authority from council ‘to confer with the Board of Police Commissioners with the view of establishing a closer relationship between the Board and the Council.’ If they did so confer – and no doubt they did – the absence of any report suggests that their efforts met with failure. In March 1931 they made the following positive proposal:

Your committee recommend that legislation be sought at the present session of the Ontario Legislature whereby the Police Commission in the future shall consist of the mayor, a county judge or magistrate to be appointed by the Ontario Government, and a third member to be agreed upon and approved by these two for a period of two years, and that provision be made for a member of the Supreme Court to hear appeals against the decisions of the said Police Commission.

That recommendation went substantially further than the original one but was adopted by council. There, however, the printed record ends. Presumably the proposal was sent to the provincial government, but if so there is no indication of how it was received. By negative evidence it must be concluded that the government was not favourably impressed. Certainly no bill was introduced and no discussion took place in the legislature.

Thus the police commission was left to develop and pursue a political course unhindered by any governmental or judicial authority. It continued to do so by majority decisions. The principal device for preventing communist – or what it deemed to be communist – meetings indoors was thinly veiled intimidation of owners or managers of public halls. Their attention was drawn to section 98 of the criminal code under which they were liable to fines if they permitted a gathering unlawful in itself or in which force or violence was advocated. At least on one occasion when such broad hints were not taken the police broke up a meeting by exploding a gas bomb. For outdoor meetings the favourite location was Queen’s Park. Existing by-laws restricting open air meetings related only to religious ones (because they had much earlier led to riots) and to such as obstructed traffic. Undeterred by the limits of legal restraints the board, in close communion with the chief constable, either prevented persons whom they considered undesirable from speaking or drove the public from the park.

Eight persons were arrested for failure to stop making speeches and two candidates in the provincial election, who were communists, were taken into custody. Newspaper reporters described dramatically scenes in the park as ‘the motorcycles roared their way,’ and as, so they said, the less agile of the public were trampled underfoot. Editorially, however, three of the Toronto dailies – the Telegram, the Mail and Empire, and the Globe – consistently supported the police commission, and there is every reason to believe that they reflected a strong body of local opinion, probably a distinct majority. In reply to criticism that freedom of speech was endangered one point was consistently made, as is illustrated by an editorial in the Globe:

The absurd effort to make it appear that Toronto’s Police Commission is opposed to ‘free speech’ was denied by Judge Coatsworth in a statement to the Globe in language more moderate than the situation merited. ‘The Police Commissioners,’ he said, ‘are in favour of free speech, and will not interfere with such unless conducted by Communists to make unlawful utterances by preaching sedition’ …

To say that it cannot be known that the Bolsheviks preach sedition until they begin to speak is as ridiculous as to say that it is not certain that a gunman whose sole desire and object is to kill will not do so until he has pulled the trigger …

The aims of the Bolsheviki are not secret. The orders from Moscow are well known …

Apologists for the Communists claim that they are but a handful of harmless fanatics not worth bothering about. They are, on the contrary, the emissaries of Soviet Russia spreading poison wherever they can do so.

The argument was not wholly without validity but it did have two serious flaws. One was that the persons who were prevented from speaking publicly were not all communists. The other was to argue that, even if sedition were woven into communist doctrine, any remarks on communism were in themselves seditious.

Those people in Toronto who overtly opposed the policy of repression were strange allies. The communists, those who sympathized with them in part, and organizations which had come under their control, formed one group. What they needed was supporters from outside it and for that reason may well have welcomed the actions of the police. Organized labour was divided, influenced on the one hand by the knowledge that communism in practice would mean the end of unions, and on the other by a tendency to favour the left rather than the right, the small man against the capitalist. The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation had a similar problem, for to form even a temporary and limited common front with communists would conflict with its attempt to purge communists from its own ranks. To the extent that any of the churches entered the debate they could not ignore the fact that communism was a sworn enemy of religion, although some churchmen emphasized different aspects of the problem. Other people in Toronto expressed, individually or in groups, the view that freedom of speech was being curtailed without any legal authority.26

In their usual patter the communists described their opponents as fascists, with no referee to point out that, from the point of view of human liberty, no difference existed between communism and fascism. And, as if to prove it, the two leading exponents of the authority of the state over the individual, Hitler and Stalin, came together in the summer of 1939 to make an unholy alliance under which peoples were to be bought and sold like cattle.

The burden of the depression was such as to divert attention from the international scene, but for those who could raise their eyes above the problem of their daily bread the outlook was sombre. Individuals wrote articles as to what Canada’s stand should be in the face of aggression and groups met to discuss the same subject. Various views were expressed, one body of opinion holding the view that collective security should be sternly enforced – but not by them. Action tore through the words. The Japanese seized Manchuria with impunity and the Italians Ethiopia. Rearmament of Germany was carried out in defiance of the Treaty of Versailles. All plans for opposing force collapsed as members of the League of Nations, Canada among them, shied away from acceptance of responsibility.

The aggressors moved forward unhindered. In 1938 Hitler took possession of Czechoslovakia and blackmailed the western powers into the Munich agreement. After it was signed individuals in Toronto were critical and hinted that they would have battled for freedom to the last ditch, but a sense of relief was the common reaction. On 1 September 1939 the German forces invaded western Poland. On 10 September Canada declared war on Germany. A week later Soviet troops entered eastern Poland and at the end of the month invaded Finland. Minor operations continued until in May 1940 the German mass attack on western Europe began.

The blitzkrieg in Belgium, the Netherlands, and France crowded minor events off the front page of newspapers. Freedom of speech was no longer an abstract question, for where the armies of the dictators triumphed no freedom for the individual could survive. Men in Toronto, and women too, enlisted in large numbers in the army and navy and in the newer air force. In the thirties some thinking on public questions had been confused and fumbling; but the people of Toronto could recognize a clear issue when they saw one, and this was a struggle for the survival of a way of life in which, with all its defects, they believed. In flights over Germany and the middle east, in the Battle of the Atlantic, and on the beaches of Dieppe young men were tragically lost who not long before had been searching for reality in a world of puzzling values.

As the tempo of campaigns increased so did the demand for munitions and other instruments of war. As in the first great war unemployment was replaced by a shortage of labour and women were needed in large numbers to fill the ranks in factories that emerged from little or nothing. Ammunition was made in several plants. The aircraft industry expanded rapidly, as did the industries concerned with chemical products, precision instruments, electrical apparatus, shipbuilding, guns, and explosives. Seen in statistical form the rise in employment was as follows:

30 September 1939 – 1 June 1942 |

57.3 per cent |

30 September 1939 – 1 July 1943 |

68.8 per cent |

30 September 1939 – 1 July 1944 |

74.1 per cent |

In the summer of 1943 the proportion of the working force in war employment was 67 per cent and in civilian employment 33 per cent.27

The second world war was a grim, businesslike affair for those abroad or at home. A regime of moderate austerity was imposed through taxation, rationing, and control of prices and rents. Some food items like tea, butter, and meat were strictly rationed. Shortage of electricity because of the demands of industry blacked out houses for some hours in each day, and the citizens scrambled in attics or summer cottages for half-forgotten oil lamps. Streets had a strange appearance with candles flickering in the windows of each house. New cars were unprocurable and so were tires for old ones. Gasoline was so narrowly limited that bicycles had a new vogue. Some of the large shops brought back into service horse-drawn delivery waggons. The number of passengers in street cars and buses rose from 154 millions in 1939 to 303 millions in 1945.

Concentration on the needs of war affected the supply of many consumer goods. It became difficult to buy a shirt, a tea kettle, or a refrigerator. Shops frowned on anyone suspected of hoarding. Some expendable activities were dropped. At the outbreak of war the entire physical plant of the Canadian National Exhibition was offered to the Department of National Defence, which gradually took it over, so that the old Military Reserve came back into its own. Similarly the Royal Winter Fair, which was held on the exhibition grounds, was suspended during the period of hostilities.

For fifteen years conditions had been abnormal. The depression had halted immigration, slowed or stopped private business enterprise, and committed a substantial proportion of municipal funds to relief of the unemployed. During the war immigration did not revive. Austerity continued after 1939 but for very different reasons. Goods were in short supply and incomes were deliberately restricted in order to channel effort into the production of aeroplanes and munitions. On these terms the economy expanded rapidly, creating a new level of industrial capacity and a large labour force trained in its use. So long as hostilities continued the effect was not materially to change the character of life in Toronto but to build up power which later could be turned into the ways of peace. The stage stood ready for whatever new play might follow when the guns were silenced.