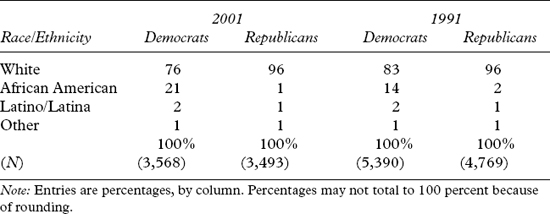

As emphasized by the previous chapter, the social forces that shape party politics in the South have become increasingly complex in the contemporary era. It is now much too simplistic to say, in V. O. Key’s oft-quoted phrase from his 1949 text, “In its grand outlines the politics of the South revolves around the position of the Negro” (Key 1949, 5). That said, race has only moved from its place as the defining characteristic of the region’s politics to a defining characteristic of party politics in the South. As the considerable amount of previous research on southern party organizations noted in chapter 1 makes clear, a void would exist in any analysis that failed to examine the cleavages created by race in the region. Still, as this chapter shows, an essential stability to the racial dynamics of party politics at the grassroots level has arrived in the South. Table 3.1 shows the race and ethnicity of the two parties’ local activists in 2001. There is much similarity between these data and those collected from activists in 1991, which are also in table 3.1.

While the percentage of Democratic activists who are African American has grown to just over 20 percent from slightly under 15 percent a decade before (and the white percentages have declined a bit), the party’s local party organizations remain decidedly biracial as has been the case since African Americans entered electoral politics in large numbers throughout the region after the passage of the Voting Rights Act (VRA) of 1965. The first two decades after the passage of the initial VRA showed, of course, not just the entrance of African Americans into the ranks of the voters and activists into the political party that, at the national level, had led the fight for the VRA (and accompanying civil rights legislation) but also the departure of whites from what was the only consequential political party in the South during the first six decades of the twentieth century. This white “departure” included both literal party switching by white Democrats who became Republicans and the absence of Democratic allegiance by new white voters and activists coming of age. So, while local Democratic Party organizations have continued to show openness to the entrance of the traditional “out” group in southern politics, as shown by Clawson and Clark (1998) in their analysis of the 1991 SGPA data, white activists, as a group, have not continued to flee the party in large numbers.

Table 3.1 Southern Grassroots Party Activists, by Race and Party, 2001 and 1991

The examination of racial and ethnic demographic data for Republicans shows the picture that has been consistent since the civil rights era as conservative whites fled to the empty shells that were Republican Party organizations in southern states. Reiterating the findings from a decade earlier, the Republican Party has shown no ability to diversify its activist ranks in terms of race and ethnicity, with only a relative handful of Republican loyalists identifying themselves as anything other than white.

Just as interesting as these now familiar racial patterns is the general absence of Latino and Latina grassroots activists in either party in 2001. Many southern communities throughout the region have been transformed by the arrival of Latinos and Latinas in the past decade; and observers, following upon 2000 census findings, have analyzed the more generalized impact of the enlarged Latino/Latina population in several southern states and in the region as a whole.1 While Spanish-language campaign appeals have become increasingly common in a number of southern states, the 2001 SGPA survey data indicate that neither party has brought Latino and Latina community leaders into their local organizations. As a result, the survey responses present no enhanced clarity about the partisan path that the first generation of new immigrants will take in the coming election cycles. While future analysis of grassroots political activists in the South will likely need to be enhanced to reflect ethnic diversity, for the purposes of this analysis the three categories of political actors—white Republicans, white Democrats, and African American Democrats—who have shaped modern southern dynamics remain the focus. The bulk of this chapter therefore focuses on differences and commonalities across those three groups, with two important—and, as will be emphasized, interrelated—questions in mind: What diagnosis is the result of this checkup on the oft-troubled Democratic biracial coalition? What distinctive contributions to the work of their party do activist African Americans, the traditional outsiders in southern politics, provide to their contemporary political home?

As numerous scholars of the modern South have noted, Democratic success in the region is dependent upon the enlivening of a biracial coalition. Black and Black (1987, 138–144) were most clear in presenting the mathematical realities present for the Democratic candidates in the region; they must pull together biracial coalitions of sufficient size and cohesiveness to win elections in the region. Most of the threats to the coalition had come from the departure of whites from the party. And, it was the shocks to the coalition that had arisen from white flight that were the appropriate focuses of analysis of the region’s politics from the time of the Voting Rights Act until the Clinton era.

Despite these jolts to the party’s fragile coalition, in their analysis of the 1991 Southern Grassroots Party Activists data, Hadley and Stanley (1998, 22) concluded that “while the biracial Democratic coalition in the South was far from rock solid, neither was that coalition on the verge of collapse.” The 2001 data indicate that fissures remain in the coalition at the activist level, but that white and African American party activists increasingly share much demographically and see the political world in similar ways; thus, the Democratic coalition no longer seems in dire threat of self-destruction at the activist level.

Some of the deepest demographic and ideological divides within the Democratic coalition are religious in their roots, as noted in the previous chapter, and serve as a potential source of angst for African Americans, who may see persons who understand their religiosity better in the other party. Yet it is these activists who are decidedly most loyal attitudinally and behaviorally to the Democratic Party. This African American fealty, combined with the perceived hostility of the modern Republican Party to their interests, therefore serves as an effective block against large-scale African American abandonment of the Democrats, at least at this level of southern party politics.

Most of the divisiveness in the post-VRA Democratic Party revolved around issues related to race. The data analyzed below show that divisions indeed persist in the Democratic Party on issues related to African American civil rights. But, more than the flight of white activists from the party that served as the key threat to the biracial Democratic coalition in the past, it is now the potential deactivation of African American activists—a set of activists who play a distinctive role in the workings of the party in the electoral arena—that is the direst threat to the continuing health of the coalition.

Intraparty divides generally arise from either of two fundamental points: who the activists are and what the activists believe. Thus, it is crucial to examine the demographic attributes and attitudinal orientations of activists. As noted earlier, the overwhelming majority of grassroots party activists in the South fall into three distinct groups that include racial and party differentiators: white Republicans, white Democrats, and African American Democrats. Therefore, the most straightforward analysis of the interaction of race and party in the region at the beginning of the new century involves the comparison of these three groups into which almost all party activists can be categorized. As the questions posed at the start of this chapter suggest, the focus of this analysis of the three groups will be on evaluating whether party or race is, on the whole, more potent as a differentiator of the attributes, attitudes, and political work of grassroots activists in the South.

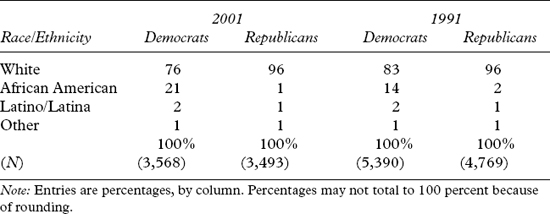

As shown in table 3.2, women activists near parity with men among white and African American Democrats. In both groups, the percentage of female activists has grown since 1991, but change is most striking among white Democrats. In 1991, only 35 percent of white Democratic activists were female, the smallest percentage in any of the three groups. In the 2001 survey results, the percentage of women among white Democratic activists has grown to 43 percent.

Findings regarding women in the ranks of African American activists reflect a similar percentage change over the decade; in 1991, 43 percent of African American Democratic activists were female; as of 2001, just under half were. Nearly one in four (23 percent) female Democratic activists in the South are now African American, showing the importance of this doubly deprived group in the party’s base. The factors that potentially promote disproportionate races of activism in this group include their work in other social organizations (especially churches), the enhanced political consciousness that comes with double deprivation, and the influence of black female elected officials (who compose a disproportionate percentage of all female elected officials in the region).2 All told, the survey data show that the openness to traditional outsiders in the Democratic Party has moved beyond race to include gender. In stark contrast, the Republican Party organizations of the region have, if anything, become less welcoming of women at the grassroots level over the same period. In 1991, 36 percent of white Republican activists were women; by 2001, the percentage had shrunk to 32 percent. The face of the Republican Party in local communities in the South is, therefore, overwhelmingly male, perhaps serving as another factor in pushing rank-and-file women voters away from the party. At the most superficial level, it is the Democratic Party that looks most like the southern communities in which it operates.

Table 3.2 Demographic Characteristics of Party Activists, 2001

Another important demographic force—geographical migration—will be examined in detail in the chapter that follows. While a full analysis can be found there, it is relevant to note that one of the most clear racial divides across the demographic profiles can be seen in one of the two areas: where activists came of age. In 1991, the largest gap on southern nativity was partisan: white Democrats and African American Democrats—86 percent and 93 percent southern-bred, respectively—were both decidedly more likely to be native southerners than were Republicans (with one in four nonnative). According to the 2001 survey, while the high levels of nativity among African Americans remain constant and while little change can be seen on this measure among white Republicans, white Democrats have become markedly less native. In 2001, over one in five came of age outside the region, only a slightly smaller percentage than among their Republican counterparts.

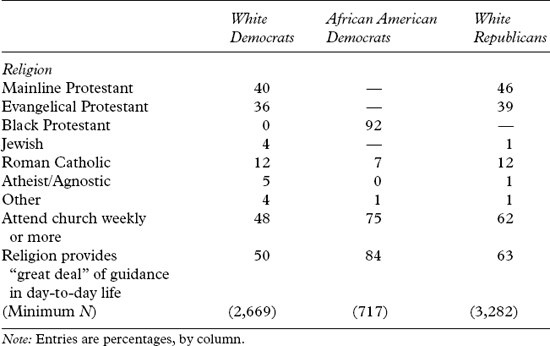

Race and party are both important in dividing activists on family income. Over half (54 percent) of African American Democratic activists have family incomes below $50,000, followed by 38 percent of white Democrats and 31 percent of white Republicans. At the other end of the income spectrum, 26 percent of the Republicans surveyed have incomes above $100,000, followed by 19 percent of white Democrats and only 8 percent of African American Democrats.

On the other most potent determinant of socioeconomic status, educational attainment, white and black Democrats are essentially indistinguishable: over one in three activists from each group have some educational training following their college graduation. The relatively small difference among activist groupings that shows itself on this demographic attribute is a partisan one with white Republicans more likely both to have attended some college and to be college graduates than their Democratic counterparts but less likely to have advanced educational experiences. All told, while differences between white and African American Democrats show themselves on the demographic characteristics presented in table 3.2, they are certainly not of a nature to create deep intraparty divisions and they are generally less striking than the differences between Republican and Democratic activists, white and black.

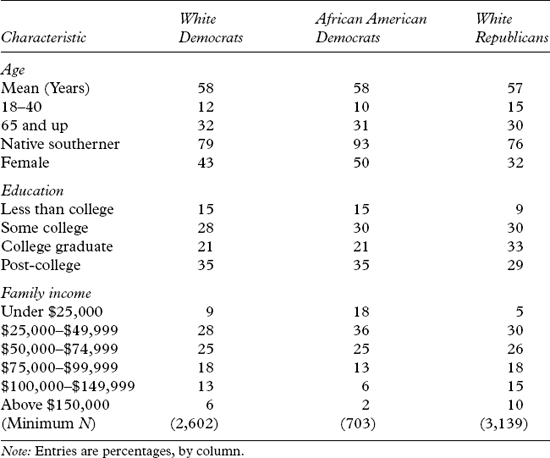

In a variety of ways, however, the three groups differ significantly on religious attributes. And, in contrast to the pattern shown with the previous demographic characteristics, white Democrats do not fall between their African American partisans and white Republicans; the middle ground on these gauges of religiosity and an acceptance of a linkage between religion and politics among the three groups is filled by white Republicans. Thus, the potential for damaging intraparty tensions within the Democratic Party activist base is clearly present here.

As shown in table 3.3, white southern Democratic activists are, as a group, anything but secularists. All but a small percentage of this group identify with a religious denomination, including 36 percent who term themselves evangelical Protestants. And, nearly half of white Democrats attend church at least once per week, and a similar percentage note the significant role that their religion provides in guiding their life decisions on a daily basis.

Still, the importance of religion in their personal lives is strikingly greater for the other two groups, especially for the white Democrats’ partisan comrades. With the exception that a larger percentage of Democrats identify themselves as Jewish or as atheist or agnostic, white Republicans appear quite similar to white Democrats in terms of the the religious affiliations with which they identify. But, white Republican activists attend church more regularly (62 percent at least weekly) and are more cognizant of the role that their religion provides for their daily lives (63 percent say a “great deal”). It is for African American Democrats, most all of whom are Protestant, that religion is an even more significant part of their lives. Three in four of the members of this group say that they attend church weekly or more often. And, an incredible 84 percent state that religion provides a great deal of guidance for their daily lives.

Table 3.3 Religious Characteristics of Party Activists, 2001

Most importantly, and similar to the worldview of many white Republicans, this is a group for whom the lines between the secular and the spiritual are not sharply drawn. As such, the influence of black Democrats’ religious beliefs on their political views are noticeable, as the next section clearly points out. But, while the hints of common ground between religious African American Democratic activists and white Republican activists are present on certain social issues, these are more than overwhelmed by the liberalism on many other issues that divides the parties, which results from African Americans’ unique religious perspective.

As shown in table 3.4, African American activists are indeed more conservative than white Democratic activists on the civil liberties issues of prayer in schools and abortion rights. On prayer in schools, only 6 percent of African American activists take the most liberal position, that is, strong opposition to school prayer. On this issue, and reflecting the trend shown in 1991 data, they look much more like Republican activists (2 percent oppose school prayer) than white Democrats (over one in five oppose school prayer). In addition, African American activists are less likely than white Democrats to see the legal protections of a woman’s right to choose abortion as appropriate. Here, however, the difference between the two groups of Democrats is tiny compared to the partisan divide that exists on the issue of abortion rights.

Table 3.4 Position on Issues for Democratic and Republican Party Activists, 2001

In addition, religious beliefs likely do mute African Americans’ support for the promotion of women’s equality in business and politics and for the expansion of civil rights protections to gay men and lesbians. The patriarchal nature of the black church (and, by extension, key components of the civil rights movement grounded in that church) has been noted by numerous scholars.3 Still, this religious-based conservatism only results in lessening the liberalism of African Americans on these issues; they remain slightly more supportive than white Democrats of promoting women’s equality in the public sphere and of civil rights expansions to gay men and lesbians in the job arena.

Table 3.5 Ideological Self-Identification of Party Activists, 2001

The larger impact of African American religious tenets on political predispositions actually comes in the form of enhancing their liberalism on a wide range of issues, thus more than outweighing any shared ideological space with Republican Party activists on social issues. While it is important not to overgeneralize, a key tenet of the teachings of most African American churches emphasizes the importance of creating social change that enhances justice, that is, the social gospel. As the key civil rights movement leader (and present congressman) John Lewis (1988, 87) puts it in his autobiography: “[Martin Luther King’s notion of] the Beloved Community was nothing less than the kingdom of God on earth.”4

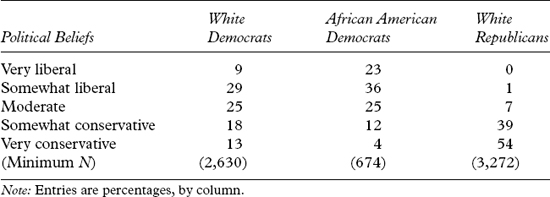

Despite the elements of conservatism present in the religious beliefs so fundamentally important to the vast majority of African American activists, these more progressive tenets of that same religious tradition are more important in shaping their ideologies. As shown in table 3.5, nearly six in ten African American activists describe themselves as “very” or “somewhat” liberal. And, despite the fact that on most issues there are not huge differences in the stances of white and black Democratic activists, “liberals” only outnumber “conservatives” among those activists by a small margin (38 percent to 31 percent). Even on this measure of ideology, it is party rather than race that matters more in dividing activists, as white Republicans are emphatically conservative ideologically.

Combined with the relative economic disadvantage of African American families, this ideology leads naturally to the stances expressed by African American activists on a variety of social safety net issues shown in table 3.4. Generally reiterating the findings reported by Hadley and Stanley using the 1991 data, African Americans have more faith than other activists in the capacity of government to be a force for protecting and promoting the interests of the less powerful in society. Still, while African Americans are more emphatic about the importance of a strong government in regulating businesses (such as HMOs) and the maintenance of government activity in funding domestic programs, the differences between white and African American Democrats pale in comparison with differences across party lines. Similarly, while African Americans are more liberal on issues related to the use of force, it is differences between Democrats and Republicans on gun control and the death penalty that are more decisive.

While the numbers vary from issue to issue (on those questions that are replicated exactly in the two surveys), on these issues white Democratic activists of 2001 have liberalized slightly from 1991. It is this movement on these non-African American civil rights, civil liberties, social safety net, and use of force issues that is responsible for most of the closing of the gap between white and African American activists on issue stances that has occurred. The more intense change—leading to the growing gap between white activists from the two parties—is the increasingly rigid and consistent conservatism of white Republican activists in the region.

So, the religious differences between white and African American Democratic activists, important as they are in creating cultural differences between whites and blacks in the South, are not serious enough to create threats to the biracial coalition. The threats to the coalition, not surprisingly considering the region’s history, are grounded in race. But, it is increasingly African American frustrations with fellow Democrats rather than the white Democrats’ sense that their party has left them behind on issues related to race that appear to present the true threat to the ongoing vitality of the Democratic coalition.

Undeniably, some of the issues analyzed previously have implicit racial components. For instance, both gun violence and the death penalty have important racial components, especially in the South. African Americans are more likely to be victims of gun violence and, even more disproportionately, they are more likely to be recipients of death sentences. But, as shown in table 3.4, it is as political issues move into explicit racial turf that the divisions between activists move from the partisan to racial. The most explicitly racial political issues about which activists were asked their views are the especial role of the government in bettering the economic position of African Americans and the appropriateness of hiring policies that would preference racial minorities. On both of these issues, white Democrats are more in sync with white Republicans than with their fellow partisans. Moreover, on these issues, the chasm between African American activists and white activists from both parties is larger than in the 1991 survey with both white groups moving in the conservative direction.

The white Democratic activists are not particularly cognizant of the sharp attitudinal divisions that show themselves on African American civil rights issues in the party. According to the survey, only 16 percent of white Democrats note a “great deal” of disagreement on racial issues within their state parties. More than twice as many African American Democrats (35 percent) are conscious of these divisions; indeed, over two-thirds of black activists (67 percent) note a “great deal” or a “fair amount” of disagreement with state parties on the issues. So, African American activists, as a minority of Democratic activists, are aware they are on the short end within their party on issues that are deeply important to them as activists.

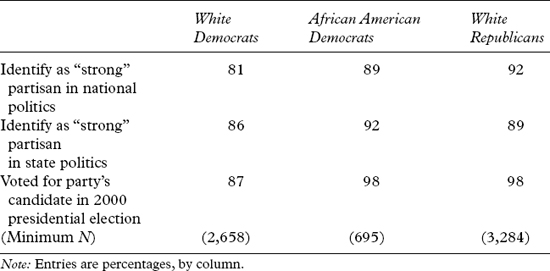

Despite these divisions about which African Americans are concerned, there is absolutely no worry that these activists will bail out on their party. They are decidedly loyal in their partisan allegiance and in their support for the party’s candidates. As shown in table 3.6, African Americans are as cohesive in their party affiliation and support for their party’s presidential candidates as are the deeply committed white Republican activists. Indeed, in state politics, African American activists are the most committed group. And, as is the case with all three groups (especially with white Democrats and their views of their national party), the strength of partisanship has grown in activists as compared to 1991.

Thus, the racial divisions noted and noticed by African American activists do not threaten their core allegiance. But, just as troublesome for Democrats is the potential muting of support of African Americans that could imperil the important work that they do in reaching out to rank-and-file African American voters at election time. As African American turnout is just as important a variable in the mathematics of modern biracial southern politics described by Black and Black as is the voting group’s cohesiveness, such prospects of lessening of the activists’ energy for party work are a real threat to the vitality of the coalition.

Table 3.6 Strength of Partisanship and Presidential Voting Behavior of Party Activists, 2001

Table 3.7 shows the activities in which county activists in the South engage on behalf of their parties. The pertinent differences among the groups are race based rather than partisan. Not surprising considering the income differences noted earlier, white activists of both parties are more likely to contribute money themselves and to engage in other activities where raising or spending money is the focus of the work. Money obviously matters in driving turnout, but African American activists report engaging in a series of activities that are much more directly related to actually “getting out the vote” on election day and in the days leading up to that event. African Americans are decidedly more likely to work in voter registration efforts, to go door to door on behalf of candidates, to distribute campaign literature, and to make get-out-the-vote phone calls. This is the time-intensive work at which volunteers are particularly effective. And, as has been shown in analyses of the relationship between contact and turnout that controls for other important variables explaining African American turnout, this work makes a significant difference in enlivening the African American component of the biracial coalition (Wielhouwer 2000).5

Table 3.7 Campaign Activities in Which Party Activists Report Having Participated, 2001

Because of the investment of time necessary for these activities to be done effectively, a threat to the biracial coalition does arise if African American activists no longer feel that their work is worthy of the personal cost. Moreover, working to get out the vote in the African American community may become even more difficult if less committed rank-and-file African Americans also come to believe that their traditional political party is no longer working on behalf of them and their community or if significant numbers of African Americans begin to be drawn to elements of the social conservative platform of the Republican Party. The potential threat to the work of African American activists is highlighted when the survey data that examine the incentives that drive grassroots activists to become and stay involved in their party are examined, a topic examined in considerably more detail in chapter 10.

Following upon the work of Clark and Wilson (1961) that provides the foundation for the analysis in chapter 10, incentives for activism can be clumped into three major categories: purposive incentives (i.e., the desire to promote public policy change), solidary incentives (i.e., the desire to interact with others on a task), and material incentives (i.e., the desire for self-interested benefits). Fortunately, the survey instrument in use in the 2001 SGPA Project tapped each of these incentives with multiple questions, the results of which for the three groups are shown in table 3.8.

Like all party activists, African American Democratic activists are decidedly purposive. For this reason, the threats that arise from doubts about the commitment of their party to their interests and ideology are potentially serious ones. As the data indicate, the two “minority” groups reflected here—African Americans and the traditional “out” party in the South, Republicans—are both more purposive than white Democrats. Interesting patterns also show themselves in two other categories. First, Democrats are decidedly more driven by solidary incentives than are Republicans. When the ideologies of the two parties are considered, it is not surprising that the antigovernment Republicans would be less inspired by working with others in activities related to the acquisition and maintenance of governmental power. Activists from all three groups are least likely to identify self-interest-oriented incentives as reasons for their involvement in party politics. But, African American Democrats are the group most likely to note their desire for personal and economic gain in party work. Considering that the other primary social outlet for African Americans, the church, is a segregated institution, it makes sense that African Americans would see this one biracial social institution in which they are involved as a venue that would give them access to the economic and social power that, in most southern communities, remains in the hands of whites.

Table 3.8 Incentives for Party Activists, 2001

This finding that African Americans are more driven by material incentives than other activists leads to an additional potentially problematic area for the Democratic coalition. While compared to the findings reported by Clawson and Clark (1998) that African Americans are enlarging their leadership roles in the party, they still lag significantly behind white Democratic activists in positions of power in local parties despite two generations of African American commitment to the Democratic coalition. In 1991, just over 6 percent of Democratic local party chairs were African American; in 2001, the percentage of African American leaders had grown to just over 10 percent indicating some movement up the party hierarchy by the traditional “out” group. But, the continuing disproportionate lack of power held by African Americans in local Democratic Party organizations is made more clear from a different cut of the 2001 data: just over 8 percent of African American activists hold chair positions as compared to 18 percent of white activists.

The 2001 Southern Grassroots Party Activists Project data, much like the survey data from 1991 analyzed by Hadley and Stanley, show a Democratic biracial coalition that is generally stable. Indeed, white Democrats’ comfort with their party seems enhanced over that of their predecessors. For most of the contemporary era, analysts of electoral politics in the South have focused on the angst about the direction of their party expressed, attitudinally and behaviorally, by white Democrats. But, if anything, the divisions that now are shown in the coalition at the grassroots level are putting more pressure on African American activists, the continued minority group in the biracial coalition that recognizes that whites see public policy issues where race is a factor in a decidedly different way than they do. These data certainly do not indicate that a bailout of the party by African American activists is on the horizon. Indeed, this is a decidedly loyal and committed group of activists. But, some warning signs appear here that, if African Americans come to feel taken for granted and/or ignored in the operations of their parties at a state and local level, then the Democratic Party and its candidates could feel the effects of African Americans’ no longer feeling that the hard work in which they engage on behalf of their party is sufficiently benefiting them. This tension—along with the enhanced diversification of one or both parties at the grassroots that will come with the entrance of Latinos and Latinas that will likely produce new ethnic and racial tensions—and the other intraparty tensions discussed elsewhere in this text indicate that the dynamics of party politics in the South in the coming decade will be increasingly complex and consequential.

1. On this issue, see, for example: Dorie Turner, “The Changing South,” Chatanooga Times Free Press, August 17, 2003; Suzi Parker, “Hispanics Reshape Culture of the South,” Christian Science Monitor, June 10, 1999; Gary Martin, “Candidates Targeting Hispanic Leaders, Voters,” San Antonio Express-News, June 4, 2003; Mark Niesse, “Census Numbers Show South Seeing Boom in Hispanic Population,” The Associated Press, September 17, 2003.

2. The initial examination of African American women active in the church and their political involvement by Clawson and Clark (2003), using the 1991 data, indicates the potency of this impetus. On this issue, also see Frederick (2003).

3. See, for instance, Dyson (2000, 197–222) and Frederick (2003). As Martin Luther King Jr. himself said in indirectly promoting the notion of separate spheres for men and women, “The primary obligation of the woman is that of motherhood” (quoted in Garrow 1986, 99). D’Emilio (2003) also writes extensively on the impact of the homosexuality of 1963 March on Washington organizer Bayard Rustin in limiting his visible role in the movement.

4. A number of authors have argued that the roots of these tenets are found in the distinctive African American religion that grew up during the era of slavery. As Genovese (1976, 252) has written, “Black eschatology emerges more clearly from the slaves’ treatment of Moses and Jesus. The slaves did not draw a sharp line between them but merged them into a single deliverer, at one this-worldly and otherworldly.”

5. Interestingly, many of these activities that focus on one-on-one communication are also disproportionately engaged in by women—another traditional “out” group in the region’s public life—according to the survey data (Barth 2002).