A timeless concern of scholars studying political party organizations has been to identify what motivates people to join and become active in the organization. Researchers have identified three major incentives that precipitate joining the organization—to attain a material benefit, to influence the making of good public policy, and to enjoy socializing with other people. People motivated by differing incentives can exert an important effect over the direction of the political party. An organization heavily dominated by ideologues who wish to enact their extreme versions of good public policy could see its hopes of electing candidates diminished by the nomination of candidates who are too ideologically extreme for the average voter. On the other hand, an organization dominated by those seeking material benefits may quickly atrophy as members soon discover that the party organization has limited rewards to distribute to its members.

It is particularly important to study how these incentives motivate people to join the party organizations in the modern American South. The South today is a truly critical region in determining the future of two-party competition in the United States. Since the mid-1960s, every American president who was a Democratic Party member hailed from the South. In the 1994 congressional midterm elections, the Republican Party finally captured a majority of U.S. House seats from the eleven southern states, which was instrumental in making the Republican Party the majority party in the U.S. House of Representatives for the first time since 1954. What motivates people to join the party organizations in the South may shed light on the types of candidates that the parties offer in future years and how competitive the parties will be. Our chapter focusing on incentives for being members of the organizations complements the study of the purist and pragmatic orientations of party organization members in chapter 9, which provides a fascinating analysis of differences between the parties and changes in orientations over the past decade, with clear implications for electoral competition in the modern South.

The study of incentives for activism in the party organizations of the new South has become even more timely over the past decade, as the Republican Party continues to make electoral gains over the historically dominant Democrats. By the year 2003, Republicans controlled both state legislative chambers in Florida, Virginia, Texas, and South Carolina; controlled the state senate in Georgia; tied the Democrats in the state house in North Carolina; held 45 percent of the seats in both Tennessee chambers; and, for the first time since Reconstruction, reached the 40 percent mark in the Alabama house and the Mississippi senate (Shaffer, Pierce, and Kohnke 2000; updated by authors). Our current analysis is further enlightened by a comparison with a similar study conducted ten years ago, as we can assess how the party organizations have changed over this most recent, turbulent decade (Shaffer and Breaux 1998).

In the modern era of multimillion-dollar campaigns, party workers remain the “foot soldiers” who work to get the party’s supporters to the polls to elect candidates to office. Given the considerable burden on a person’s time and peace of mind that such heavy responsibilities may place on the individual party organization member, one must ask why anyone would want to join a party organization. In other words, “What’s in it for me?” The answer to this question is vital in sustaining political party organizations that are essential to American democracy. It is also important in explaining how American democracy operates and what kinds of choices it offers to voters.

Our theoretical framework is that of incentive systems in organizations more generally, a pioneering theory developed by Peter B. Clark and James Q. Wilson over forty years ago. Clark and Wilson (1961) argued that political and nonpolitical organizations were distinguished by the different kinds of incentives that explained why people became members. They also pointed out that shortages in the availability of some incentives would force the organization leader to seek out other ways of attracting members, and that chief executives of organizations could rely on a diversity of incentives rather than just one.

Clark and Wilson proposed that incentives could be classified into three broad types: material, solidary, and purposive. Material incentives were tangible rewards that could be translated into a monetary value. Examples of organizations employing material incentives were a taxpayer’s association that sought to reduce the taxes of its members and a neighborhood improvement group that sought beautification projects that raised the property values of its members. Historically, urban political machines, such as Mayor Richard Daley’s in Chicago, that rewarded their members with patronage jobs and government contracts were clearly relying on material incentives to attract party workers. Solidary incentives were intangible rewards lacking monetary value but instead were based on personal satisfactions derived from the act of associating with other people. Individuals might join a group because they found it enjoyable to socialize with the other people in the group, or because they had a sense of identification with the group, or because they derived some social status from being a group member. Such incentives for joining the group were not dependent on the outcome of what the group actually accomplished; therefore, members were typically flexible about the goals of the group. An example of a solidary organization offered by Clark and Wilson was a women’s luncheon group that members found to be sociable and fun. Purposive incentives also provided intangible rewards, but unlike solidary incentives these rewards were derived from the outcomes of group membership instead of merely the act of being a member. Organizations might seek such goals as eliminating corruption and inefficiency in government or some other change in public policy. Examples of purposive organizations provided by Clark and Wilson were reform and social protest groups, such as the NAACP.

While Clark and Wilson provided an invaluable theoretical framework, it was left to other scholars to apply this theory to modern political party organizations by systematically collecting information about party workers and scientifically testing this incentives theory with real-world data. Studying party organizations in a rural Illinois county and a suburban Maryland county, Conway and Feigert (1968) learned that people sought precinct leadership positions primarily for purposive reasons, such as a belief that it was their civic duty or because of a desire to influence public policy. Studying political party precinct and ward chairs in five communities in North Carolina and Massachusetts, Bowman, Ippolito, and Donaldson (1969) found purposive incentives most important, solidary incentives second in importance, and material incentives least important reasons for why these organization leaders were active in politics.

A related question is not merely why people join a party organization but whether their motivations change over time. Some studies suggest an evolution away from purposive incentives over time, as organization members find material and purposive goals difficult to achieve and increasingly enjoy such solidary rewards as social contacts and intense party loyalty that organizational membership provides (Conway and Feigert 1968; Bowman, Ippolito and Donaldson 1969). Other studies suggest a greater stability of incentives over time, with purposive incentives generally being most important in motivating people to first become politically active and remaining the key motivation keeping people politically involved as the years go by (Ippolito 1969; Hedges 1984; Miller, Jewell, and Sigelman 1987).

While a number of scholars have focused on why people join or remain in a party organization, very few have examined what may motivate people to rely on a particular type of incentive. For instance, why are some people more motivated by solidary incentives to join a party, while others are motivated by purposive incentives? Bowman and Boynton (1966a) found that party leaders in their five communities often came from politically active families and that they were more likely to have been encouraged by other party members to seek the party leadership post rather than to have taken the initiative by themselves. In a study of party delegates attending the 1972 and 1976 Republican national convention, Roback (1980) found that the two most important reasons that delegates first became interested in politics were socialization by their family and their own interest in issues or social movements. Neither study specifically examined why one person may be motivated by one incentive to become active in politics while another person may be motivated by a different incentive.

In the previous Southern Grassroots Party Activists Project, Steed and Bowman (1998) found that party members coming from politically active families and who have been active in the party organizations for a longer time were more likely to be consistently strong partisans (feeling intensely identified with and close to their party at both the national and state levels) than other organization members. Unlike the other studies cited, Steed and Bowman also specifically examined a possible source of purposive, solidary, and material incentives. They found that strong partisans were motivated to become involved in party work by all three types of incentives, while weak partisans rated purposive, solidary, and material incentives as less important motivations.

Given the importance of the solidary-material-purposive incentives theoretical framework to the study of political party organizations, it is somewhat surprising that so few studies have sought to examine what impact these different incentives may have on the behavior of the organization. One pioneering work is by Conway and Feigert (1974), who found that the effect of purposive motivations on task performance of party workers in two counties studied depended on the environment. In the county having the higher socioeconomic level, party members motivated by purposive incentives relied more on communicating the party’s principles to voters, while in the lower socioeconomic county, party members motivated by the same incentive focused more on increasing voter turnout. The impact of incentives, particularly purposive incentives, on support for presidential candidates has been more extensively studied, as political activists motivated by purposive incentives are particularly likely to favor more ideologically extreme candidates who mirror their own issue orientations (Roback 1980; Abramowitz, McGlennon, and Rapoport 1983; Hedges 1984).

A more comprehensive examination of the sources as well as the effects of solidary, purposive, and material incentives was the previous 1991 study of county executive committee members of the Democratic and Republican Parties in the eleven southern states (Shaffer and Breaux 1998). Southern grassroots party activists as a whole were motivated more by purposive incentives than by solidary or material incentives. Republicans were more motivated than Democrats by purposive incentives, while Democrats were reliant more on solidary and material rewards. Incentives were also found to be related to party members’ issue orientations and to whether their stylistic orientation was pragmatic or purist. All three incentives appeared to motivate party members to be more actively involved in political campaigns at local, state, and national levels, an intriguing finding that suggests that a diverse range of personal motivations, even potentially divisive purposive incentives, may contribute to the vitality of party organizations.

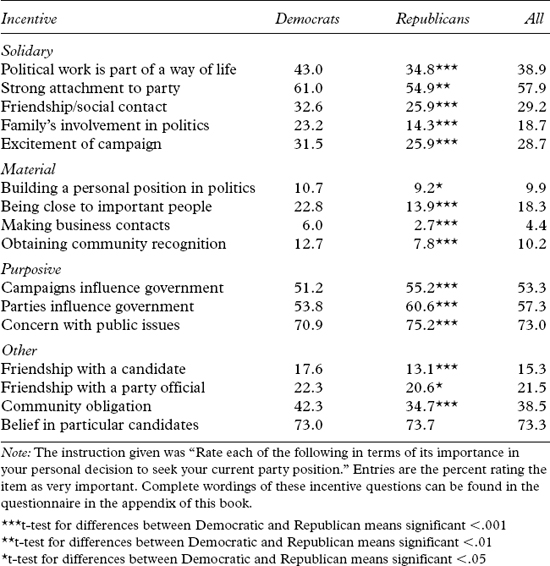

We now turn to an analysis of the 2001 SGPA data, a data source described in chapter 1. Examining all sixteen questionnaire items that measured solidary, material, purposive, and other reasons for seeking one’s current party position, we find that the motives cited as “very” important are candidate-centered, purposive, and party-oriented motivations. Nearly three-fourths of workers of both parties sought their current party positions to support a candidate they believed in or because of a concern over issues, and over 50 percent cited party attachment or viewing party and campaign work as a vehicle for influencing government. Examining each group of incentives separately for the two parties combined, purposive incentives were most frequently cited, with over 50 percent of aggregated party workers rating each of the three purposive indicators as very important (table 10.1: last column). Solidary incentives were second in importance, cited as very important by 19 percent to 58 percent of party activists. Material incentives were least important, rated as very important less than 20 percent of the time. The relative importance of these incentives for seeking one’s current party position is very similar to what it was among southern grassroots party activists ten years ago and to what was found in previous studies (Shaffer and Breaux 1998; Bowman, Ippolito, and Donaldson 1969; Hedges 1984).

Table 10.1 Incentives for Seeking Current Party Position

Despite this commonality of incentive rankings among Democrats and Republicans, there is a difference in emphasis on incentives between the two parties. Republicans are somewhat more likely than Democrats to rate all three items measuring purposive incentives as very important, while Democrats are more likely than Republicans to rate all five solidary items and all four material items as very important (table 10.1). These results were also found among southern grassroots party activists ten years ago, and they suggest a rational response by the two southern parties to their political environment. Southern Republicans who found an ideologically compatible home in a national Republican Party that was basically conservative were therefore motivated by issue-oriented purposive incentives to join their state or local party organization, while Southern Democrats who were often out of touch with their “liberal” national party found themselves relying more on interpersonal solidary or self-seeking material incentives that were divorced from policy concerns. One potential problem for the southern Republican Party stemming from its members’ greater focus on purposive incentives is conflict within the organization, as heated disputes over the goals of the party may cause significant divisions among party members. Divisions within each party’s membership in terms of “pragmatic” versus ideological “purist” goals, and how these conflicting orientations may affect the party’s candidates chances of getting elected, were examined in chapter 9.

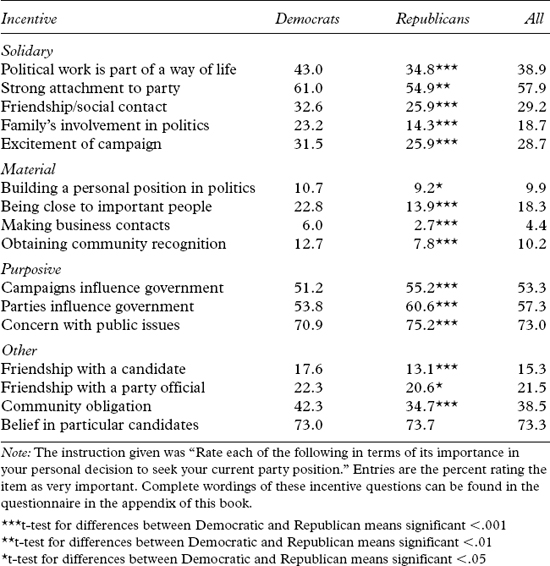

Table 10.2 Change in Incentives for Seeking Current Party Position

The essential stability of incentives among southern grassroots party activists over the past ten years is illustrated in table 10.2, which directly compares responses on each questionnaire item between 1991 and 2001. Change among all activists (table 10.2: last column) was within four percentage points on every item except candidate support and a concern with issues, two items that workers in both parties cited as increasingly important to them. A more careful examination of change over time for the three incentive groups yields some interesting patterns. Solidary incentives appeared to become slightly more important to both parties’ activists since 1991, suggesting an increasing relevance of the political parties to southerners as organizations that provide intangible rewards resulting from socializing with other people. Yet purposive incentives also became increasingly important over the years, particularly among Democrats, suggesting a slight change in the nature of the southern Democratic Party into a more ideologically concerned organization. Today’s Democratic activists are beginning to mirror the more issue-oriented nature of the southern Republican Party, though in an opposing ideological direction. These results are consistent with the findings in chapter 9 that Democrats have become somewhat more purist over the past decade and that both parties have become more ideologically polarized.

In the remainder of this chapter, we examine how party members having these solidary, material, or purposive incentives for joining the organization may differ in other ways from members lacking such motivations, and how these incentives may shape party workers’ activities. We employ a data reduction technique called principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation, which combines all sixteen incentive items into three major scales (factors) that correspond to the solidary, material, and purposive incentives. These three factors accounted for 47 percent of the variation in the sixteen items’ intercorrelations, and the questionnaire items loading (related or correlated to) most highly on each factor are identical to how the items are grouped together in table 10.1 and table 10.2. Four other items either loaded on a minor “personal friendship” factor or loaded on more than one factor and for theoretical reasons are omitted from our analyses.

For ease of interpretation before performing the factor analysis, we recoded each of the motivational incentives to range from a low score of 1 for the incentive being not important at all to a high of 4 for the incentive being very important. Therefore, in all succeeding analyses, groups having the higher mean factor scores rate that incentive as more important than groups with a lower mean factor score. For instance, Republicans, who have a mean purposive factor score of .12, rate purposive incentives as more important than Democrats, who have a mean purposive factor score of –.12. Solidary incentives are more important to Democrats (mean solidary scale score of .13) than to Republicans (mean solidary scale score of –.13). Finally, material incentives are also more important to Democrats (mean material scale score of .08) than to Republicans (mean score of –.08).

In each of the following three sections, we determine through multiple regression whether differences in the means of the incentives across theoretically relevant groups are substantively significant. This advanced methodological technique permits us to rule out other possible explanations for why membership in a group is related to an incentive being cited as important.

The considerable literature on political socialization points out the importance of parents as a key source of the average citizen’s political orientations, though fewer studies have examined whether parents affect the socialization of political party activists. Bowman and Boynton (1966a) and Roback (1980) are notable exceptions, though their finding that party officials and national convention delegates often come from politically active families does not explain why or how the family is an important motivating factor. Steed and Bowman (1998) find that having a politically active family can result in party organization members being consistent and intense partisans, though they also are not able to identify specifically why or how the family is influential over their offspring. We examine two important attributes of parents—their political activity levels and their party identifications—with questionnaire items asking respondents to recall whether their “parents or other relatives” had “ever been active in politics beyond merely voting” and to recall each parent’s “party affiliation at the time you were growing up.” Parents were either active or not active in politics, and we combined each parent’s party identification item into one scale of parental partisanship that measured whether both parents held the same party as their offspring or whether one or both parents adhered to a different party.

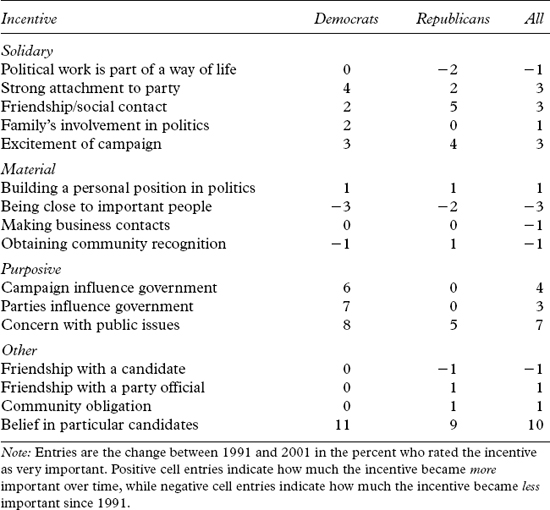

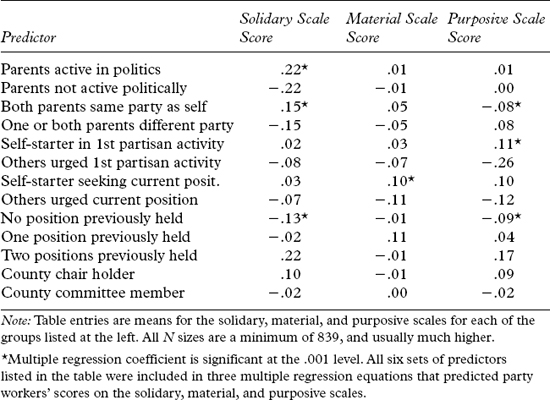

Only the solidary incentive scale was related to having politically active parents, as respondents with more politically active parents rated solidary incentives as more important than those with politically inactive parents, as one might expect from the interpersonal nature of the solidary incentive that includes the family as one personal influence (table 10.3). Patterns varied depending on whether respondents shared their parents’ partisanship. Party workers who kept the same partisanship as their parents may have been socialized by their families to value solidary incentives, which included attachment to a political party, as such incentives were more important to activists sharing their parents’ partisan orientations than they were to respondents who disagreed with their parents’ partisanship. On the other hand, party workers who disagreed with their parents’ party identifications rated purposive incentives as more important than did those having the same party as their parents. This suggests that the ideological views of some respondents may have led them to choose to adopt a political party different from their family. For instance, conservative Republicans whose parents had been Democrats were likely motivated by their concern over issues to defect and to join the modern Republican Party.

Party organizations must have members in order to exist and to carry out their functions. They either actively seek out new members or decide whether to admit people who take the initiative to join their group. Bowman and Boynton (1966a) found that most local party officials were recruited by other party members rather than self-recruited, while Hulbary and Bowman (1998) found that both mechanisms were important in recruiting southern grassroots party activists to their party office. Generally unexamined by the literature is how these differing recruitment mechanisms may be related to the incentives that motivate party members, though Hulbary and Bowman’s (1998) discovery that purposive and material incentives are more related to self-recruitment while solidary incentives are more linked to recruitment by others is a notable exception.

Table 10.3 Incentives and Possible Sources of Activism

We examined the differences between being a self-starter or being recruited by others for two separate decisions—the decision to “first become involved in party politics” and the decision to “seek your current party position.” For both questionnaire items, those who responded that a major consideration was that they had decided “to participate/run pretty much on my own” were classified as self-starters, while other party members were regarded as being more influenced by other people, such as party or elected officials. Interestingly enough, while we also find that being a self-starter is related to material and purposive incentives, these incentives are related to differing decisions. Being a self-starter in the initial decision to become involved in party politics is related only to purposive incentives, while being a self-starter in the later decision to seek a party position is significantly related only to material incentives (table 10.3). Those urged by other people to become active in party politics and to seek a party position rate purposive and material incentives as less important than self-starters, and there are no significant differences in solidary incentives between self-starters and those urged by other people to be active.

Other studies have generally agreed that purposive incentives are particularly important in motivating people to become active in partisan politics, while disagreeing over whether purposive or solidary incentives are most important in keeping people active as the years go on (Ippolito 1969; Hedges 1984; Miller, Jewell, and Sigelman 1987; Conway and Feigert 1968; Bowman, Ippolito and Donaldson 1969). Our chapter suggests that there may indeed be an evolution in one’s motivations as one gains more experience in party politics, but that change is most likely to occur among self-starters. Self-starters may first become active in party politics for the idealistic and perhaps naïve belief that they can really “make a difference” in public policy, but as time goes on their realization of their limited impact on governmental policies may cause some to seek out more tangible material rewards for seeking a party office. It is intriguing that while other studies have argued that material incentives are so scarce that party members rely more on solidary incentives as reasons to remain in the organization, we find in the modern South that material rewards remain important incentives, as least for self-starters.

Since previous studies found that purposive or solidary incentives were especially important motivations for remaining active in a party organization and we found that material incentives were important to one group of activists, it is logical to expect that incentives may be related to two likely rewards for years of party experience—becoming a county party chair instead of remaining a mere county committee member, and having previously held party or appointed public office positions. Whether respondents were county chairs or county committee members was one of the items collected by the survey; we created a scale from three questionnaire items to measure the number of previous party or appointed public office positions held. We found that incentives were related to leadership experience in the party organizational activity, though not to the current occupation of a leadership position.

Those reported to have previously held two or more party positions or appointed public offices rated purposive and solidary incentives as more important incentives, compared to those who had held no previous party or public position (table 10.3). Furthermore, differences in the importance of purposive and solidary incentives between those having and those lacking previous positions remained after controlling for other possible correlates of incentives. Holding previous political positions was significantly related to solidary and purposive motivations, even when taking into account other factors such as having politically active parents with the same partisanship as their own, being self-starters in the decisions to first become active in party politics and to seek one’s current position, and being a county chair or committee member. Such was not the case for currently being a county party chair instead of a committee member. While county chairs rated purposive and solidary incentives as more important compared to mere county committee members, this distinction disappeared after multivariate controls for all of the other predictors listed in table 10.3. A likely explanation is that county chairs tended to hold more previous party/public positions than did county committee members, and number of previous positions was the more important of the two factors in shaping reliance on solidary and purposive incentives.

To summarize, each of the three incentives for occupying one’s current party position are related to social background and experience factors in different ways. Having politically active parents may socialize party workers into the importance of solidary reasons for being active in a party organization. Those who continue to hold the same party identification as their parents are even more motivated by solidary incentives, while those who have switched from their parents’ partisanship are more motivated by issue-oriented purposive incentives. Issues often motivate a person to take the initiative to first become involved in party politics, as self-starters rate purposive incentives as more important than do other party workers. As time goes on, party workers find multiple reasons for remaining active in the organization. Those holding two or more previous party or public positions, for example, rate solidary and purposive incentives as more important than do those in their first party position. In addition, those who took the initiative to seek their current party position regard material incentives as more important motivations than those who weren’t self-starters.

It is important to examine how incentives are related to party workers’ issue orientations, their partisan intensity, and their purist versus pragmatic orientations toward party work for two major reasons. First, it sheds light on why people become and remain active in a party organization, a vital question for the very existence of the organization. For instance, what would induce a liberal or even a moderate person to be active in a party as conservative as is today’s southern Republican organization? Second, how issues or partisanship are related to motivational incentives can have important implications for the operation and electoral success of the party. If people motivated by a purposive orientation to join a political party are also more ideologically extreme than other party members, and if their decisions as party members are motivated more by a desire to promote their ideological goals rather than by a more pragmatic desire for their party to win at any cost, then they may support candidates who are so distant from the average citizen that they are unelectable.

The literature disagrees over whether people view policy issues in a unidimensional manner consistent with a liberal-conservative framework, or in a multidimensional framework reflecting different issue areas (see chapter 8 for a review of this controversy). With fourteen agree-disagree issue items, seven federal spending on programs items, and one ideological self-identification question in our questionnaire (see the appendix for the specific items), we addressed this controversy and simplified the data by conducting a principal components factor analysis with varimax rotation. Two factors explained 51 percent of the variance in the items’ inter-correlations, with cultural issue items loading most highly on the first factor and domestic economic spending items loading most highly on the second factor. After examining two correlation matrices of the items loading most highly on the first and second factors, we determined that agree-disagree items on school prayer, the death penalty, and defense spending best measured cultural issues and that federal spending on the public schools, social security, and health care best measured domestic economic issues. The economic and cultural issue scales were created through simple summation, as the codes of items within each issue area ranged in the same ideological directions, and each scale was trichotomized so that each category contained virtually the same number of categories. The resulting scales resulted in more cultural conservatives (53 percent) than economic conservatives (11 percent), and more economic liberals (50 percent) than cultural liberals (13 percent), as one would anticipate from the policy views of average southerners (Breaux, Shaffer, and Cotter 1998).

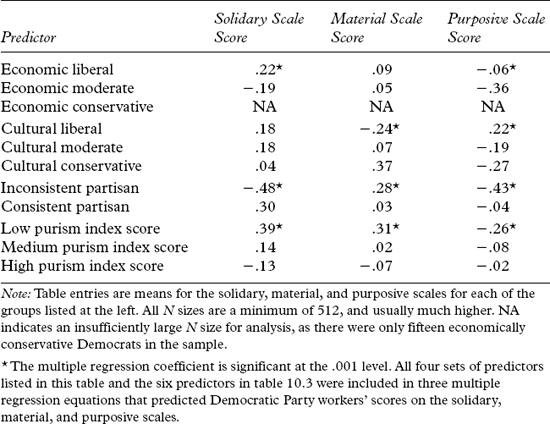

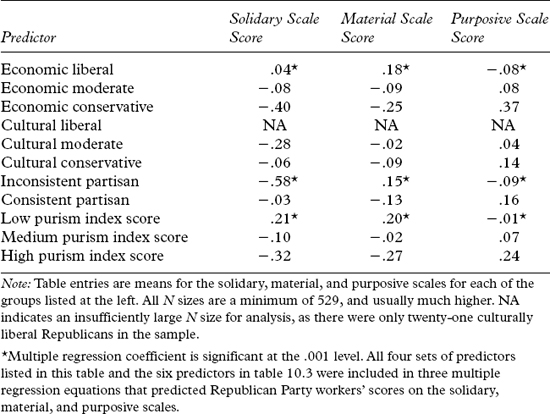

The relevance of incentives to party activists, particularly purposive incentives, clearly depends on the dominant ideology of the national party. Among Democrats, both economic and cultural liberals were more motivated by purposive incentives to seek their current party position than were economic or cultural moderates or conservatives (table 10.4). Among Republicans, economic conservatives were more motivated by purposive incentives than were economic moderates or liberals (table 10.5). A similar pattern existed in the 1991 study, illustrating how contemporary southerners who are motivated by issues to be active in the party organizations are able to sort themselves out into the party that best reflects their policy preferences—liberals joining the Democratic Party and conservatives joining the Republican Party (Shaffer and Breaux 1998). Other studies have also pointed out how party sorting by ideology is going on in the modern, two-party South but have not examined the role that incentives play in this process (Steed 1998).

Issue differences in material and solidary incentives are less clear. Material incentives do appear to provide some motivation for ideological deviants to remain in a party organization where they are in the philosophical minority. Thus, culturally conservative Democrats rate material incentives as more important than do culturally liberal or moderate party colleagues, while economically liberal Republicans rely more on material incentives than do economically moderate or conservative Republicans. However, material incentives are unrelated to economic issues among Democrats or to cultural issues among Republicans. Solidary incentives may bear some relationship to issue orientations for Democrats, as economic liberals rate these incentives as more important than do nonliberals, though cultural issues are not significantly related to solidary incentives among Democrats. The relationship between solidary incentives and issue orientations among Republicans is contradictory, as economic liberals and cultural conservatives rate solidary incentives as more important than do other issue groupings. In conclusion, while purposive incentives help activists sort themselves out into the party that best represents their positions on issues, material incentives operate to ensure that the parties are broader tents than they otherwise would be. Such broader tents retain at least some ideological dissenters, thereby enhancing the party’s electoral hopes of attracting more middle-of-the-road voters.

Table 10.4 Incentives and Issues, Partisan Intensity, and Purist-Pragmatist Attitudes among Democrats (Means of Incentive Scales)

Table 10.5 Incentives and Issues, Partisan Intensity, and Purist-Pragmatist Attitudes among Republicans (Means of Incentive Scales)

Intensity of one’s partisanship can benefit a party by encouraging party members to actively support the organization (Steed and Bowman 1998) or by dampening the potentially divisive effects of ideologically extreme party activists in the nomination of candidates (Abramowitz, McGlennon, and Rapoport 1983). This topic is discussed in chapter 6. We defined intense or consistent partisans as those having strong identifications with their party at the national and state levels who also voted for their party’s presidential candidates in 1996 and 2000, while all other party workers were classified as less intense or inconsistent partisans. Party workers’ responses on all four of these questionnaire items were correlated at the Pearson r level of .95 or higher, justifying combining these items into a single scale.

We found that consistent partisans in both parties were more motivated by purposive and solidary incentives than were inconsistent partisans (table 10.4 and table 10.5), confirming Abramowitz, McGlennon, and Rapoport’s (1983) argument that a purposive orientation does not conflict with one’s psychological commitment to a party or with support for nominating an electable candidate. Inconsistent partisans in both parties were more motivated by material incentives compared to consistent partisans. The 1991 study found that organization workers who were more partisan tended to have higher motivations on all three incentives than did less partisan workers. Therefore, the greater material motivation of inconsistent Democratic and Republican partisans today suggests that workers less psychologically committed to the party, as well as ideological dissidents, are able to find some tangible reason for remaining active members of their party.

To measure the concept of purist-pragmatist orientations, or the extent to which party workers value promoting ideological purity over party unity and a broad electoral appeal that helps to win elections, we employed the trichotomized index of purism discussed in chapter 9. Workers in both parties who were low on the purism index, and therefore more pragmatically geared toward “winning” elections, rated material and solidary incentives as more important than did other party workers. This was also the case in our 1991 study, suggesting that the pragmatic politician who avoids divisive issues remains an important element in party politics in the South. Members of both parties who were high on the purism index and therefore more geared toward seeking ideological purity, rated purposive incentives as more important than did other party members (table 10.4 and table 10.5). This is a change from the 1991 study, when purposive incentives were more important to purist Republicans but not to purist Democrats. It is also interesting to recall chapter 9’s finding that Democrats today are a little more purist in orientation than they were in 1991. The emergence of purposive incentives as a motivating force for purist Democrats as well as Republicans suggests that the modern southern Democratic Party may be on its way to becoming as “ideological” an organization as the conservative southern Republican Party was in the latter years of the twentieth century.

Issue orientations, partisan consistency, and purist orientations are clearly interrelated with purposive, solidary, and material incentives among today’s southern party activists. Activists who are from the ideologically dominant wing of their party, who are consistent partisans, and who are purists all rate purposive incentives as more important in their decisions to seek their current party positions, compared to other members of their party. In both party organizations, consistent partisans and pragmatists rate solidary incentives as more important than do inconsistent partisans and purists. More marginalized party members, such as inconsistent partisans and those in the ideological minorities of their parties, who also tend to be pragmatists, are motivated more by material incentives. These patterns persist even after controlling for other possible explanations for differences in incentives among issue, partisan, and purist groups of activists. Six multiple regression equations that predicted the solidary, material, and purposive scale scores for each party separately from the ten predictors in the preceding and current sections of this chapter yielded the statistical significance levels noted in table 10.4 and table 10.5.

Studies have shown how solidary, material, and purposive incentives can motivate people to become politically active and to join a party organization, but very few scholars have explored whether such incentives influence the activities of people after they join the organization. Conway and Feigert (1974) argued that party organization members who were motivated by purposive incentives stressed different campaign activities in differing environments, stressing communicating the party’s principles to voters in higher socioeconomic environments and seeking to increase voter turnout in lower socioeconomic areas. Shaffer and Breaux (1998) discovered that all three incentives may play a role in motivating party members to generally be more involved in political campaigns at the local, state, and national levels than other party members, though they did not examine the specific ways that members became more active.

While not linking up specific activities with party members’ solidary, material, or purposive incentives, previous studies do suggest what types of activities we should focus on. Bowman and Boynton (1966b) and Ippolito and Bowman (1969) found that local party officials viewed their roles in terms of the most important things that they did in their jobs, and those tasks were primarily campaign-related tasks and party organizational work. Bowman and Boynton (1966b) also explored the communication patterns of party officials, finding that party members were more likely to talk to local and state public officials about public problems than to national officials, though no study has attempted to link communication patterns with the three types of incentives.

We examined southern grassroots party activists’ behaviors in their general role as party organization members, in their more specific roles as activists in political campaigns, and as members of an intraparty communications network. Party workers were asked how important each of fourteen different activities was in their “current party position,” and whether they performed each of thirteen different activities in “recent election campaigns.” They were also asked how frequently they communicated with the county and state party chairs; the county, state, and national executive committee members; and government officials at the local, state, and national levels. To identify conceptually distinct types of party and campaign activities and of communication patterns, we subjected all three sets of questions to three separate principal components factor analyses with varimax rotations.

Activities performed by party workers in their current party positions did indeed form two separate factors or dimensions—working with voters and maintaining the party organization. Activities performed in recent election campaigns formed three separate dimensions, which we labeled as working with media to get the candidate’s message out, mobilizing voters, and supporting the candidate by distributing literature or raising money. Intraparty communication formed two separate dimensions—communications at the local level where 73 percent of activists fell into the high communications category, and communications at the state and national levels where only 17 percent fell into the high communication group. To relate these two communication scales, the two party position activity scales, and the three campaign scales to solidary, material, and purposive incentives, all seven of these scales were dichotomized into higher and lower activity groupings.

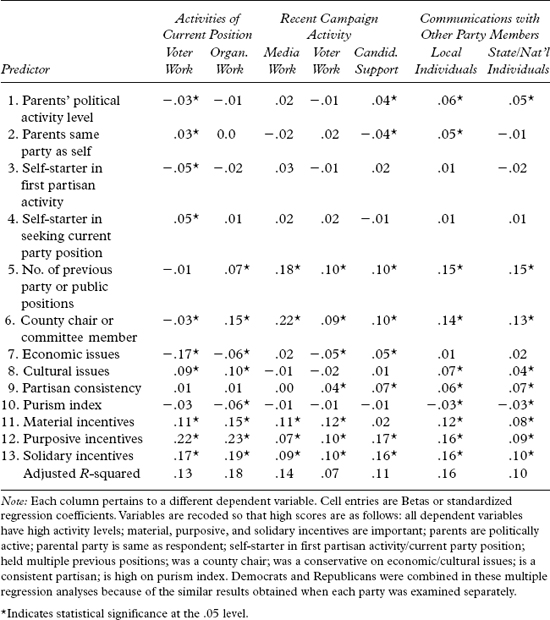

Our examination of a diverse range of party and campaign activities reinforces the conclusions of our 1991 study. Party members who were most motivated by all three types of incentives—material, purposive, and solidary—were more politically active than those less motivated by each type of incentive. Party activists who report that working with voters and maintaining the party organization were important activities that they performed in their current party positions have higher scores on the solidary, material, and purposive incentive scales, compared to party members who view these tasks as less important parts of their jobs (table 10.6).

Table 10.6 Incentives as Possible Sources of Activism (Means of Incentive Scales)

Furthermore, each incentive continues to exert direct effects on party work with voters and on organizational matters, even after controlling for the other two incentives and all other possible sources of party activism (the predictors included in table 10.3, table 10.4, and table 10.5). Purposive incentives appear to be the most important motivating force for both activities, while solidary incentives are second in importance, and material rewards are the least important incentive (table 10.7). Other factors exerted limited or inconsistent effects on activity levels, with county chairs and those previously holding party positions being more active than other party members on organizational maintenance tasks but not in working with voters, and liberals on economic issues but conservatives on cultural matters being slightly more active on both types of tasks.

Table 10.7 A Multivariate Analysis of Sources of Activism

Turning to acts performed in recent election campaigns, party organization members who are more active in working with the media or with voters during campaigns rate material, purposive, and solidary incentives as more important, compared to organization members who are less active in these types of campaign activities (table 10.6). Regarding direct support of candidates during a campaign, those more active rate purposive and solidary incentives as more important than do the less active, while no significant differences exist in terms of material incentives.

Once again, these patterns are unchanged after simultaneously controlling for all three incentives as well as all other possible explanations for campaign activity. Material rewards are the most important incentives for working with voters and with the media, but purposive and solidary incentives also directly stimulate these campaign activities (table 10.7). Purposive and solidary incentives are essentially equally important in encouraging candidate support activities, while material rewards do not affect the amount of this type of campaign activity. Political experience and leadership positions also affect campaign activity levels, as county chairs and those having previously held party/public positions were more active in all three types of campaign activities than were county committee members and those with less party experience. Indeed, these two nonincentive factors were more important than all three incentives in explaining campaign work with the media and were equally important as incentives in explaining campaign work with voters, though less important than purposive and solidary incentives in explaining candidate support.

Given the highly motivated nature of the more active members of the party organization, one might expect that those who have the most communication with other party and public officials are similarly motivated by a diverse set of incentives. Such is indeed the case, as party organization members who often communicate with local or state/national political figures rate material, purposive, and solidary incentives as more important than do organization members who seldom or never communicate with political figures (table 10.6).

Once again, each type of incentive remains a statistically significant predictor of both levels of intraparty communication, even after simultaneously controlling for the other two incentives and all other possible sources of communication activism. Purposive and solidary incentives are essentially equal in importance in shaping frequency of communications, while material incentives are slightly less important (table 10.7). Once again, leadership as a county chair and having previous party/public experience are also important factors, being virtually as important as the incentives in shaping frequency of local communication, and more important than the three incentives in shaping frequency of state and national communications. Parental socialization and party intensity/consistency may also play a role in interpersonal communication levels, as members whose parents were politically active and members who were intense and consistent partisans have more communications with local, state, and national figures than do less intense partisans having less active parents.

Our 1991 study suggested the intriguing possibility, unexamined by the literature, that such diverse motivations as purposive, solidary, and material incentives could all encourage organization members to be active workers for the party rather than to be party members in name only. This chapter provides strong evidence that all three incentives do indeed encourage party members to be active in a number of different ways. As party organization members, all three incentives encourage members to work with voters as well as to work on maintaining the party organization. These incentives also inspire party members to be active in political campaigns in many ways—directly supporting candidates, working to get the campaign’s message out, and mobilizing voters. Even between campaigns, material, purposive, and solidary incentives stimulate party members to communicate with other party or governmental officials at the local, state, and national levels. Previous studies of southern grassroots activities have found that county chairs are more active than other party members on party maintenance activities and on campaign activities (Feigert and Todd 1998; Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998). Rather than doing the work of the party entirely by themselves, today’s county chairs and those who have previously served in such leadership posts can seek to motivate other members of their party to actively support the party’s goals by relying on policy appeals, an appeal to material self-interest, and the appeal of working with others in a common cause.

Clark and Wilson (1961) theorized that people joined organizations in general to obtain material, purposive, or solidary incentives, while subsequent scholars applied the theory specifically to party activists and learned that they were particularly motivated by purposive and solidary incentives to be active in party organizations (Conway and Feigert 1968; Bowman, Ippolito, and Donaldson 1969; Ippolito 1969; Hedges 1984; Miller, Jewell, and Sigelman 1987). Our study finds that southern grassroots party activists are most motivated to seek their current party positions by purposive incentives and are also motivated by solidary rewards but are least influenced by material gains. We also find different emphases for the two major parties, as Republicans are somewhat more motivated by purposive incentives, while Democrats are generally more influenced by solidary and material rewards.

Fewer studies have sought to explain why different people are motivated by different incentives, or how those incentives may affect people after they become members of a party organization. One exception is Steed and Bowman (1998), who found that strong partisans were motivated to become involved in party work by all three types of incentives, while weak partisans rated purposive, solidary, and material incentives as less important motivations. Other exceptions focus on the types of presidential candidates supported during the nomination process, as party activists motivated by purposive incentives were found to be more likely to back more ideologically extreme candidates (Roback 1980; Abramowitz, McGlennon, and Rapoport 1983). Our chapter finds that family socialization, being a self-starter, and being experienced in party matters affect what incentives most motivate a person to seek a party position. We also find that issue orientations, partisan intensity and consistency, and having a purist or pragmatic orientation affect reliance on particular incentives. Despite people having differing incentives for seeking a party position, all three incentives have a similar effect on how active one is as a party member. Relying on any of these incentives can stimulate an organization member to be active in maintaining the organization, communicating with other party members, and helping to elect the party’s candidates to office.

Scholars debate over the effects of incentives on the vitality of an organization. Clark and Wilson (1961) claim that purposive incentives may be harmful by generating divisive debates over the goals of the organization. Abramowitz, McGlennon, and Rapoport (1983) point out that party activists motivated by purposive incentives may nevertheless be intensely committed to their party and that such intense partisan commitments may encourage support for electable candidates. We found that purposive incentives help to maintain organizational distinctiveness by sorting activists into the party that is most ideologically appropriate for them, as liberal Democrats and conservative Republicans were more motivated by purposive incentives than were their party colleagues. Material incentives helped to ensure that the party did not become too ideologically narrow, as ideological dissidents in both parties were motivated more by material rewards than were other party members.

While the operation of these incentives is generally positive for the vitality of a party organization, some developments suggest a more challenging future for the parties in the South. Purposive incentives—always important in the southern organizations—appear to have become even more important over the last ten years. While pragmatists rate solidary and material incentives as particularly important, purists are more motivated by issue-oriented purposive incentives. The increased importance of purposive incentives, as well as their association with an orientation that stresses ideological purity over nominating candidates who are electable, suggests that both parties may face some challenges in offering attractive candidates to the southern electorate in future years, a topic addressed in chapter 8.