What kinds of people choose to be active in political party organizations? This simple question has been the focus of considerable research. Attention has been given to this topic because many political analysts believe that the nature of the party organization is affected by the characteristics of its active members. In particular, both commentators and scholars have voiced concerns about the problems created by uncompromising ideologues who emphasize ideological purity rather than electoral victory. Some observers view such activists as a force that can impede electoral success by making the party too ideologically rigid. Others argue that the concerns over this new breed of party activist are unjustified. Regardless of which viewpoint is correct, the extent of purist orientations among party activists is a relevant feature of party organizations.

This study analyzes county-level political party activists in the South, drawing on the SGPA data described ealier in this book. The focus of this study is on the purist-pragmatist orientations of these grassroots activists, with the aim of (1) determining how purist or pragmatic contemporary activists are, (2) examining how these attitudes differ across party lines, (3) analyzing the sources of these orientations, (4) examining the consequences of these attitudes for party activity, and (5) analyzing change over time in the levels of these purist-pragmatist orientations in each party. As we discussed in chapter 1, local political party organizations are worthy of study, and analyzing them in the contemporary South is particularly worthwhile given the substantial recent political change in the region. The results of this investigation therefore should be of interest to both scholars interested in political party organizations and scholars concerned about southern politics.

The concept of purism, as used in this study, is a simple one. It refers to the relative emphasis that a party activist places on policy issues versus electoral success. It is an attitude toward candidate and party behavior, and it can be conceptualized as a continuum. At one end of the continuum are extreme purists, who would not have the party or its candidates compromise at all on issues in order to win more votes. These purists favor ideological correctness regardless of its electoral consequences. At the other end of the continuum are extreme pragmatists. They are concerned solely with victory and care nothing about ideological correctness. For them, positions on policy issues are simply a means by which the party’s candidates win votes. Few if any activists will be complete purists or pragmatists. Almost all will fall somewhere between these two extremes. But activists can be distinguished by their degree of purism or pragmatism, and those differences are the focus of this study. As a shorthand notation, we can refer to this concept as purism or as purist orientations, recognizing that being low on purism means being more pragmatic.

Scholarly interest in purist orientations was stimulated by Wilson’s (1962) study of what he termed “amateur” versus “professional” activists in local Democratic Party organizations. Many subsequent studies focused on this distinction (Conway and Feigert 1968; Dodson 1990; Hitlin and Jackson 1977; Hofstetter 1973; Ippolito 1969; Maggiotto and Weber 1986; Roback 1975; Soule and Clarke 1970). Wilson’s concept was multidimensional, including not only purism but also incentives for involvement and attitudes toward party democracy (Hofstetter 1971). This multidimensional nature of Wilson’s concept has complicated research on this topic, as some studies have focused on one dimension of the amateur-professional distinction, while other research has focused on other dimensions. For this reason, it seems preferable to use the term purism in this study, as it clearly identifies the dimension that we are examining here. Another aspect of Wilson’s concept, the incentives for involvement, is discussed in chapter 10, and the findings of that chapter nicely complement the conclusions of this chapter.

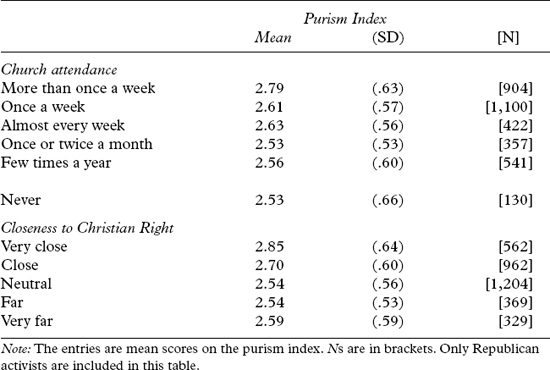

Existing research has focused on several aspects of purism or related concepts. Perhaps the question that has received the most attention is how purism is related to ideology. The general hypothesis is that those who are high in purism are more likely to be ideological extremists, meaning strong liberals among Democrats and strong conservatives among Republicans. This relationship has been found by a number of studies (Abramowitz and Stone 1984; Clarke, Elliott, and Roback 1991; Hitlin and Jackson 1977; Soule and McGrath 1975).

The rise of purist activists who also are ideologically more extreme led some researchers to predict dire consequences for the parties (Kirkpatrick 1976; Ranney 1975; Soule and McGrath 1975; Wildavsky 1965). Much of this research was conducted during the 1960s and 1970s. Subsequent research has taken a different view, finding that even though activists may be more purist, they remain concerned with winning and constrained by strong party loyalties (Abramowitz, McGlennon, and Rapoport 1983; Hauss and Maisel 1986; Maggiotto and Weber 1986; Stone and Abramowitz 1983). Even if earlier concerns about purist activists were overblown, the potential consequences of purist orientations remain a relevant topic. As we shall see from the following analysis, there is reason to believe that these attitudes could have consequences for the behavior of activists.

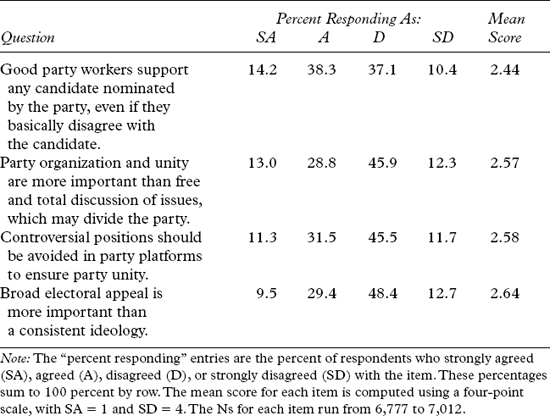

Several items in the 2001 SGPA questionnaire were aimed at measuring purist orientations; all of the items are similar to ones used in previous research (Abramowitz and Stone 1984; Prysby 1998b). The question wording and distribution of responses for these items are in table 9.1. All have a good balance between those in agreement and those in disagreement. The most lopsided responses were to the last item, but even here there is about a 60/40 split. Moreover, for each item, those simply agreeing and disagreeing outnumber those strongly agreeing and disagreeing, respectively, so that the distributions are roughly similar across the items. The four items in table 9.1 were used to construct an index of purism, which is simply the mean score on the four items for all respondents who answered at least three of the items.1 Nearly all of the respondents did answer at least three of the four items, so there is very little missing data on this item. For each item, disagreeing represented the more purist orientation, so scores on the purism index run from 1.0 to 4.0, with the high score representing the most purist orientation.

The distribution of scores on the purism index is displayed in figure 9.1. As we can see, scores are bunched in the middle, with only a small proportion of respondents at either end of the continuum. However, there is substantial variation on this item. About 31 percent of the activists have scores of 3.0 or higher, and around 23 percent have scores of 2.0 or lower. A score of 3.0 would result from disagreeing (but not strongly disagreeing) with each item, and a score of 2.0 would result from agreeing (but not strongly agreeing) with each item.2 The difference between these two scores seems meaningful. It also is worth noting that nearly one-half of the activists have purism index scores between 2.25 and 2.75, indicating that their responses to the index component items were a mixture of agreement and disagreement.

Table 9.1 Purist-Pragmatist Attitudes among Southern Political Party Activists, 2001

Figure 9.1 Distribution of Purism Index Scores for Southern Political Party Activists, 2001.

Existing research on southern political party activists has found that Republicans tend to be more purist and more motivated by policy issues (Moreland 1990a; Prysby 1998b; Shaffer and Breaux 1998). The same finding emerges from these data. Figure 9.2 shows the distribution of scores on the purism index for Democrats and Republicans. The differences are not enormous, but Republicans do fall more to the right on the bar chart, with a mean score of 2.64, compared to 2.47 for Democrats. Moreover, there are some significant cumulative differences in the distributions. About 36 percent of Republican activists have purism index scores of 3.0 or higher, compared to only about one-fourth of the Democrats. Similarly, around 28 percent of Democrats have purism index scores of 2.0 or lower, whereas less than one-fifth of Republicans have such scores.

The higher levels of purism among Republican activists in the South would seem to follow from the fact that they are more ideologically extreme, at least in comparison to southern Democrats, a pattern discussed in more detail in chapter 5. The consistently conservative position of Republican activists is not surprising, as the growth of the party in the region has been based in large part on a clear conservative message. Democrats, on the other hand, have been a diverse party, encompassing a wide range of ideological groups. In 1991, for example, Republican activists were solidly conservative, whereas Democrats were spread across the ideological spectrum, with a substantial number identifying as conservative (McGlennon 1998b; Steed 1998). In 2001, Republicans were even more conservative, with over 90 percent identifying as such and over one-half calling themselves strongly conservative. Democrats moved to the left over this ten-year period, so that by 2001 close to 60 percent called themselves liberal, although only about one-fifth claimed to be strongly liberal, and many identified themselves as moderate or even conservative (see chapter 5 for more detail on the ideological identifications of activists). If purism is related to ideological extremism, this would seem to explain why Republican activists display higher levels of purism, as compared to Democrats.

Figure 9.2 Distribution of Purism Index Scores by Party for Southern Political Party Activists, 2001.

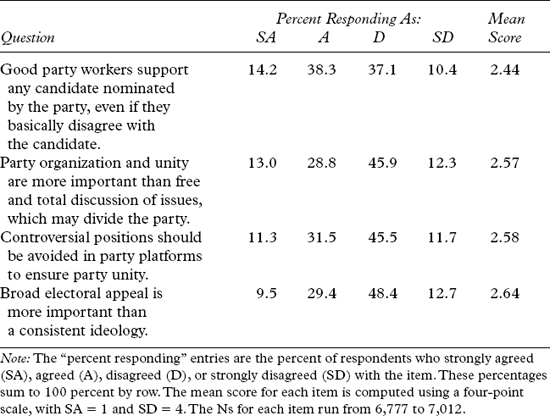

In order to test this explanation, we can examine purism levels by ideological position. The relevant data are in table 9.2. Among Republicans, purism is related to ideology. Those identifying as strongly conservative have the highest mean purist score, and the moderates have the lowest. However, the same pattern is not present for Democrats. The “very liberal” Democrats have purism scores that are only slightly greater than the moderate Democrats, and the “somewhat conservative” Democrats have purism scores that are slightly greater than those displayed by the “very liberal” Democrats. Finally, purism scores for Republican activists are higher even when corresponding ideological groups are compared. For example, the “very conservative” Republicans are substantially more purist than are the “very liberal” Democrats. If we measure ideology by using the respondent’s responses to specific issues rather than the respondent’s self-classification, we get much the same results (Prysby 2003).3

Table 9.2 Purist-Pragmatist Attitudes by Ideology and Party for Southern Political Party Activists, 2001

Overall, these data suggest three conclusions. First, purism is related to ideological extremism, but the relationship is much stronger for Republicans than for Democrats. Second, the greater ideological extremism of Republican activists is only a partial explanation for their greater purism, as highly conservative Republicans tend to be more purist than highly liberal Democrats. Third, while ideology and purism are related, the connection between these two factors is far from perfect. There are moderates in both parties who are strongly purist, and pragmatists can be found among the very liberal Democrats and the very conservative Republicans.

In order to better understand the relationship between purism and general ideological orientation, it may be helpful to look at significant cleavages within each party. Among southern Republicans, the split between conservative Christians and others is the division most cited by scholars of southern politics (Baker 1990; Baker, Steed, and Moreland 1998; Green 2002; Layman 1999; Rozell and Wilcox 1996). The emergence of the Christian Right as a political force in southern politics is discussed in more detail in chapter 2. Here we will simply note that in many places, a division emerged between more traditional Republicans, who are concerned with economic issues, and religious conservatives, who emphasize social issues. A common perception is that these conservative Christians form a more ideologically extreme and more purist group within Republican ranks, one that in the eyes of some may hamper Republican electoral success by creating an extremist image for the party.

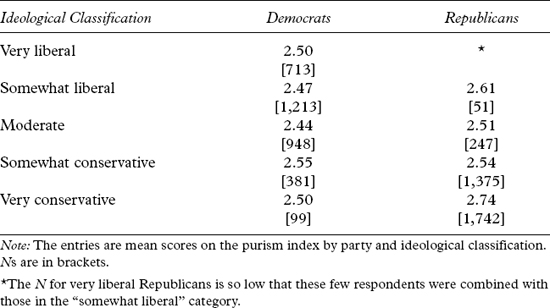

Table 9.3 presents data on the relationship of purism to religious orientations among Republican activists. Two measures discussed in chapter 2 are used here to identify religious orientations: (a) church attendance and (b) reported closeness to the Christian Right. In both cases, the relationships are clear. Purism increases with more frequent church attendance and with increasing closeness to the Christian Right (except that there is a slight increase in purism among those who feel very distant from the Christian Right). Those who say that they attend church more than once a week and those who feel very close to the Christian Right display particularly high purism scores compared to other Republican activists. In fact, these two groups have purism scores that are substantially greater than the scores of those who selected the next closest response on these two items, that is, those who attend church weekly (but not more than once per week) and those who feel close (but not very close) to the Christian Right.

The relationship between purism and religious conservatism suggests that certain social issues may be especially related to purism among Republican activists. Advancing conservative positions on such social issues as abortion, gay rights, and school prayer are key components of the Christian Right political agenda. To investigate the impact of specific issue orientations on purism, the thirteen policy issue items that were used to form the issue orientation index discussed earlier were examined separately. For almost every issue, Republican activists who hold the most conservative position are above average in purism. There are several issues where this tendency is particularly strong: abortion, government action to improve the status of women, gay job discrimination, gun control, aid to minorities, and government services and spending. With the exception of the last issue, all are social issues, and the first three are issues that traditionally have been emphasized by the Christian Right. These findings support the conclusion that high purism scores among Republican activists result much more from strong conservative positions on social issues, especially those stressed by the Christian Right, than from attitudes on economic or social welfare issues. It is important, however, not to exaggerate the connection between purism and religious conservatism among Republican activists. It would oversimplify reality to characterize all southern Republican activists who have strong purist orientations as supporters of the Christian Right or to assume that all supporters of the Christian Right are strong purists.

Table 9.3 Purist-Pragmatist Attitudes by Religious Orientations for Republican Southern Political Party Activists, 2001

Among southern Democrats, race is generally considered to be the most divisive issue (Bullock and Rozell 2003b; Glaser 1996; Hadley and Stanley 1998; Moreland, Steed, and Baker 1987). Holding together the biracial coalition that is necessary for victory is a difficult task, a topic discussed in chapter 3. A number of race-related issues potentially can divide this coalition, including questions of affirmative action, aid to minorities, welfare programs, and redistricting. While race may be the dominant cleavage among southern Democrats, it is not strongly related to purism. White southern Democratic activists have a somewhat higher purism score than do their black counterparts (2.50 versus 2.35). More important, on the issue of affirmative action, those who are more supportive are no more purist than those in opposition. Also, those who strongly support government aid to minorities are not higher in purism. In general, purist orientations among Democratic activists are not as clearly tied to issue orientations as they are among Republicans. There are some issues for which more liberal Democratic activists tend to be those who are more purist (e.g., gay job discrimination, school prayer, capital punishment), but there are many other issues where there is little or even no connection between purism and issue position (e.g., abortion, school vouchers, government services and spending, affirmative action, aid to minorities, regulation of managed health care, flat income tax). This, of course, is consistent with the earlier finding that ideological orientation is more weakly related to purism among Democratic activists than among Republican activists.

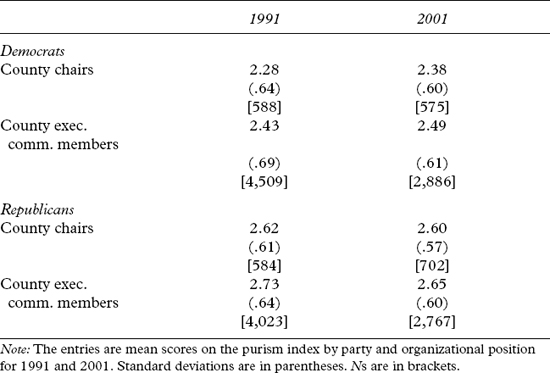

The 1991 SGPA survey contained similar items relating to purism. The findings from that study also found that southern Republican activists were more purist than were Democrats (Prysby 1998b). With the benefit of data at two points in time, we can examine shifts in the level of purism for each set of party activists. Table 9.4 presents mean purism scores broken down by year, party, and party position. The party position breakdown is simply between county chairs and other members of the county executive committees. County chairs tend to be more pragmatic than the other activists, either because more pragmatic individuals are selected to be chairs or because the position of chair entails responsibilities that encourage greater pragmatism. Since county chairs comprised a greater proportion of the 2001 sample than they did in 1991, a more accurate picture of changes in purism is obtained by including this breakdown in the analysis.

The patterns of change are interesting. Among Republicans, purism declined somewhat, at least among those who were not county chairs. This decline is not what we would have expected given the earlier observation about how purism is related to ideology. Between 1991 and 2001, Republicans became even more conservative, as reported earlier. This rightward movement in ideological orientations did not produce more purist orientations, a very interesting development.

Among Democrats, the opposite development has taken place. Southern Democratic activists became more purist between 1991 and 2001. During this period, Democratic activists also moved to the left ideologically, becoming more clearly liberal in 2001 than they were ten years earlier. However, it would be hard to attribute the increase in purism among Democratic activists to the ideological shift because, as we have seen in the preceding analysis, purism is not particularly related to ideology among Democrats.

Table 9.4 Purist-Pragmatist Attitudes by Party and Organizational Position for Southern Political Party Activists, 1991 and 2001

In order to better understand the sources of these shifts in purism in both parties, a cohort analysis of purism scores in 1991 and 2001 is helpful. Such an analysis allows us to examine two competing explanations for these changes. One possibility is that the shifts in purism result from individuals becoming more or less purist with more years of involvement. Another possibility is that generational (or other) replacement is responsible for the changes. Those who became active after 1991 may have different purist orientations than those who ceased to be active after 1991.

Table 9.5 presents purism scores by year, party, and cohort group (defined by years of activity). By reading along each row, one can see how each cohort group changed between 1991 and 2001. By examining each column, one can see the relationship between years of activity and purism for each point in time. By comparing the 1991 entry with the 2001 entry on the preceding row, one can compare actives with the same years of experience at two points in time.

Table 9.5 Purist-Pragmatist Attitudes by Length of Activity and Party for Southern Political Party Activists, 1991 and 2002

Among Democrats, there is little change in any cohort over the ten-year period. For example, those who had between eleven and twenty years of activity in 1991, and therefore would have between twenty-one and thirty years of activity in 2001, had a mean purism score that was almost the same at both points in time (2.47 in 1991 versus 2.48 in 2001). Furthermore, purism is related to length of activity. Those with fewer years of activity tend to be more purist. Those who had no more than ten years of activity in 2001 (i.e., those who became active after 1991) have the highest purist score (2.60). This pattern indicates that replacement is the source of the increase in purism among Democratic activists. Those who had been active the longest in 1991 were the most pragmatic. Many of them were no longer active in 2001 (the Ns indicate a very substantial drop-off), and they were replaced by activists with significantly more purist orientations.

Republicans have a pattern that differs from that for Democrats. Among Republican activists, we see a decline in purism within each cohort. For example, those who had been active from one to ten years in 1991 went from a purism score of 2.80 in 1991 down to 2.69 in 2001. Slightly greater declines took place in the other groups. Moreover, although higher purism is associated with fewer years of activity among Republicans, the 2001 purism score for those who became active after 1991 is only slightly higher than the 1991 purism score for the group with the most years of activity. Replacement is not the source of the decline in purism among Republican activists; the decline is due to changes among existing activists. The small replacement effect actually worked against a decline in purism.

In sum, different processes operated within each party to produce the shifts in purism.4 Why did individual change lower purism among Republicans while replacement heightened purism among Democrats? We can only speculate on the answer to this question. It does seem that among Democratic activists, those who in 1991 had been active for a very long time were a very pragmatic group. The very low levels of purism among the oldest Democratic activists may have resulted from the very heterogeneous nature of the party in earlier decades. Before Republicans became competitive up and down the ballot, southern Democrats represented a wide range of ideological positions. This fact may have made it very difficult for strong purist orientations to emerge among those who were active at that time. As many of these older local party leaders ceased to be active in the following ten years, it was not surprising that their younger replacements would be more purist. Having grown up in an era during which the Democrats were becoming more ideologically distinct, they inevitably would be more purist. What is interesting, however, is that those who were active in 1991 do not appear to have changed their purist orientations in the subsequent ten years, even though the party was changing its ideological character.

We also can speculate about the reasons for the patterns of change among Republicans. The lack of a generational effect may simply be due to the fact that the older Republican activists were fairly strongly purist already. These were individuals who were motivated to be involved in party politics by issues and who believed in a strong conservative message. The more interesting point is that those who were active in 1991 tended to become less purist by the end of the decade. This change in the orientations of existing activists might be a response to the improvement in electoral fortunes for Republicans, especially farther down the ballot. Having captured majority control of Congress and a majority of the southern congressional seats during the 1990s may have given Republican activists a different perspective. With more Republicans in office and with the prospect of even more gains, such as in state legislative races, Republican activists may have become more concerned about electoral appeal than they were a decade ago. If this is the case, it shows an evolution of the party that was produced by the improved electoral situation, which might in turn suggest further change if the party makes substantial gains in state legislative elections during the next decade.

Purist orientations may influence how activists are involved in party activities. One hypothesis is that those with more purist orientations are less likely to be involved in party activity. This hypothesis follows from the view that purists will work hard for candidates whom they truly believe in but may be unwilling to be active on behalf of candidates who do not excite them. Purists may be less willing to remain active in the party year in and year out and less willing to devote time to routine aspects of party maintenance. This relationship has not been thoroughly investigated, but some recent research into southern political party activists has found support for this hypothesis (Feigert and Todd 1998b; Prysby 1998b; Shaffer and Breaux 1998).

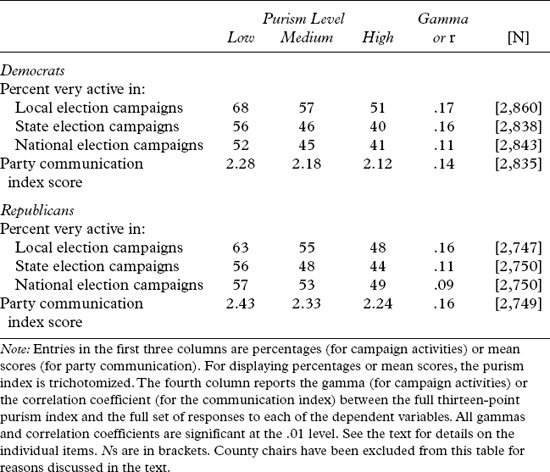

To investigate this hypothesis, we can examine the relationship between purism and two different measures of party involvement. The first measure is based on respondent reports of the extent of campaign activity, behavior that is covered in more detail in chapter 11. Respondents were asked how active they had been in national, state, and local campaigns (responses were on a four-point scale, from very active to not at all active). A second measure is based on respondent reports of intraparty communication, discussed in chapter 12. A set of eight questions asked the respondents how often they communicated with other individuals or groups in the party (responses were on a four-point scale, from very often to never). An index of party communication was formed by taking the mean score on these items.5

Table 9.6 shows how purism is related to these two measures of party involvement for Republican and Democratic activists. Because county chairs tend to be both more active in their party and less purist, as was noted earlier, they are not included in the following analysis. Their inclusion would tend to inflate the relationship. For ease of presentation, scores on the purist index have been trichotomized into low, medium, and high purism. However, the measures of association reported in the tables (gamma for the campaign activity measures; correlation coefficients for the communication index) are based on the full thirteen-point purism index and the full set of responses to each of the measures of party activity or involvement.

Table 9.6 Relationship between Purist Orientations and Party Activity by Party for Southern Political Party Activists, 2001

Among Democrats, activists with higher purism scores are less likely to report high levels of campaign activity. The differences here seem meaningful; for example, two-thirds of the Democrats with low purism scores report being very active in local elections, whereas only one-half of those with high purism scores report such activity. Also, those with higher purism scores are less likely to report high levels of communication with others in the party, indicating that their lower level of party involvement and activity is not limited to election campaigns. The pattern for Republican activists is very much the same. Republican activists with high levels of purism are less likely to be very active in campaigns at all levels, and they also are less likely to communicate with others in the party. Moreover, the strength of these relationships, as measured by gamma or r, is fairly similar for both Democrats and Republicans.

The consistency of the findings across several measures of party involvement and across party lines indicates that purist orientations do have consequences for the parties. A high concentration of activists with high levels of purism is likely to result in more activists who are involved on a selective basis. The party organization naturally would prefer fully committed activists who will be highly involved on a sustained basis. On this basis, high levels of purism would be regarded as less desirable by party leaders. However, we should note that the impact of purism on involvement is not enormous, and current levels of purism in either party do not seem to present a serious problem. In particular, the higher levels of purism among Republican activists do not seem to result in their being less active than their Democratic counterparts.

The findings of this study should be of interest to scholars concerned about political party organizations. The analysis shows that there are substantial differences in the purist-pragmatist orientations of grassroots activists. Furthermore, these purist-pragmatist orientations are related to ideology, with more purist activists holding more extreme ideological positions. However, the relationship of purism to ideology is much stronger among Republicans than among Democrats, indicating that the link between these two variables is not as clear and direct as some might think. Purist orientations have potential consequences for party organizational activity. Purists are less likely to be deeply involved in the party organization on a sustained basis, indicating a potential problem if purist orientations rise to a high level. Finally, there was a decline in purism among Republican activists during the 1990s, a change that may indicate that purism is influenced by the environment; more favorable electoral situations may lead activists to become less purist in their attitudes.

This study also has something to say about southern politics. Southern Republican activists tend to be more purist than southern Democratic activists. However, the difference in purism now is less than it was in the early 1990s. While Republicans have become somewhat less purist, Democrats have become a little more purist. This development has occurred even though the parties are ideologically farther apart now than they were a decade ago. Despite the fact that southern Republicans became more strongly conservative, they became less purist, just the opposite of what we might have expected. Among southern Republican activists, purism is related to ideology; strong conservatives are the most purist. In particular, high levels of purism are centered among supporters of the Christian Right and among those who hold strongly conservative positions on social issues, although these are not the only Republicans who have strong purist attitudes. Given the potential divisiveness of Christian Right activists in the party, the decline in purism surely is pleasing to Republicans who emphasize electoral success. Among Democrats, strong purist orientations are not clearly linked to an identifiable group of activists. Contrary to what we might expect, the Democratic activists who are strong purists are not much more liberal than those who are more pragmatic. For this reason, the increase in purism among Democratic activists is not likely to present a problem for the party. In fact, the increase in purism stems largely from the loss of older activists who were very pragmatic in their attitudes. The newer and younger Democratic activists are more purist than the activists whom they are replacing, but they still are less purist than the newer and younger Republican activists.

1. The individual items all had four-point response scales (strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree). In each case, strongly disagree was the most purist response. Each item was scored to range from 1 (strongly agree) to 4 (strongly disagree), so that a higher mean score on the index would indicate a higher level of purism. The four items have intercorrelations that range from .23 to .48.

2. Of course, disagreeing with each of the four items is not the only way to obtain a 3.0 index score. One could have agreed with two items and strongly disagreed with two others, for example.

3. An index was formed from thirteen questions on specific issues. The thirteen items dealt with a flat income tax, the desirable level of government services and spending, government action to ensure jobs and good living standards, government regulation of managed health care, affirmative action, government aid to minority groups, government efforts to improve the situation of women, job discrimination against gays, handgun control, capital punishment, school vouchers, abortion, and school prayer. The individual items all had four-point response scales (strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree). Each item was scored to range from 1 (most liberal response) to 4 (most conservative response), so that a higher mean score on the index would indicate a more conservative orientation on the issues. For a more detailed report of this analysis, see Prysby (2003).

4. There are some limitations to these data. The only measure of length of party activity was a question that asked respondents how long they had been active in politics beyond just voting. Of course, such political activity might represent campaign work for candidates, or it might represent involvement in a political party but not at the level of executive committee membership. Thus, those who said in 2001 that they had been active in politics for over twenty years might not have been a member of a county party executive committee in 1991. For this reason, our cohorts are not exactly comparable groups, but this measure of the length of involvement in party activity should be close enough to suffice. Moreover, a complementary analysis yields similar results. Instead of defining the cohort groups in terms of years of activity, we can define them by age. An analysis similar to that reported in table 9.5 but using age cohort groups was conducted, and the results of that analysis support the conclusions drawn from table 9.5. Among Democrats, there is very little change in purism for any age cohort between 1991 and 2001; their over-increase in purism during this ten-year period is not a result of increasing purism of existing activists. On the other hand, purism steadily declines with age in both 1991 and 2001, so the younger Democratic activists in 2001 were substantially more purist than the older activists whom they were replacing. Republican activists have a different pattern. Each of the age cohorts declined in purism between 1991 and 2001. Generational replacement contributed nothing to this decline; the youngest Republican activists in 2001 are slightly more purist than the oldest activists in 1991. See Prysby (2003) for a more detailed report of this analysis.

5. The eight items asked respondents whether they communicated very often, often, seldom, or never with different party members (e.g., county chair, county executive committee members) or elected officials (e.g., local officials, state officials). See the questionnaire for more details on these items. The items were scored from 4.0 (very often) to 1.0 (never), so that a higher mean score indicates more communication.