Politics often involves conflict. Thus, important for understanding southern politics is knowledge of the region’s political conflict. Similarly, understanding how southern politics have changed requires knowing how the nature of the South’s political conflict has shifted. Among the most frequent forms of political conflict are disputes over public policies. In this chapter, we use the results of the Southern Grassroots Party Activists surveys to examine three aspects of policy-based conflict in the South—interparty policy conflict, intraparty policy conflict, and change in policy conflict over time.

First, we compare the policy opinions of the region’s Democratic and Republican Party activists. The results of this examination will show which policy areas most or least divide the region’s parties from one another. Second, political conflict does not, of course, only occur between parties. It can also take place within a party. Thus, this chapter also examines the level of policy agreement within each group of party activists across a number of specific issues. This examination of intraparty divisions shows which policy areas are potential “wedge” issues that a party may use to generate dissension and splits within its opposition. Finally, we compare the results of the issue-related items contained in both the 1991 and 2001 SGPA studies. The results of this examination show how the size and character of the region’s political conflict have changed.

By most accounts, the policy preference of political activists would have provided little insight into the region’s politics during the days of the Solid South. Then, according to V. O. Key (1949, 37, 142, 186), political conflict within the region centered around splits along “irrelevant” lines, on matters upon which everyone already “agrees ought to be done,” or on an “appeal to support the home-town boy.” While variations existed among southern states, issue-based debates and divisions generally played an exceptionally small role in the region’s partisan politics. “Issues?” Key (1949, 94) quotes a Florida county judge as declaring, “Why, son, they don’t have a damn thing to do with it.”

However, as discussed in chapter 1, during the last half century the Solid Democratic South has disappeared and a new, more competitive, politics has developed within the region. Investigations of the region’s political transformation, as well as discussion of partisan change generally, suggest that policy questions played an important role in the demise of the South’s one-party political system.1 Studies examining the issue-related measures contained in the 1991 SGPA survey also show the importance of policy questions in the recent politics of the region (Brodsky and Cotter 1998; McGlennon 1998b). Thus, unlike previously, an examination of partisan issue differences is likely to shed considerable light on the nature of contemporary political conflict in the South.

Further, it is appropriate to investigate the character of the region’s political conflict by examining the issue opinions of party activists. These individuals, through their work in political campaigns, attendance at party conventions and caucuses, and performance of the organization’s mundane but necessary administrative tasks, have an important influence on the issue stances taken by the parties. These issue positions, in turn, affect who wins the parties’ nominations for office, the focus and substance of election campaigns, the types of voters the parties attract, and the actions of officeholders in government.2 Recent research exploring the influence of “elites” on citizens’ policy preferences suggests that the policy views of party activists may also have an important impact on public opinion and, thus, the nature of political conflict generally (see, for example, Zaller 1992).

The 2001 SGPA survey contains several measures of the policy or issue views of the region’s party activists. First, respondents’ general policy views were measured by an item asking the activists to describe their “political beliefs” as (1) very liberal, (2) somewhat liberal, (3) middle of the road/moderate, (4) somewhat conservative, or (5) very conservative. Second, the questionnaire contains a set of items in which respondents were asked their opinions about fourteen different domestic issues. In order to make the results of the analysis of the different types of policy measures more comparable, the issue items were recoded so that the most conservative response was given a score of 5, while the most liberal response received a score of 1. Finally, the 2001 study includes seven items asking respondents if “federal spending should be increased, decreased, or kept the same” in seven policy areas. Again for purposes of comparability, responses to these spending items were recoded so that scores ranged from 1 (decrease spending) to 5 (increase spending).3

We begin the analysis by considering regionwide patterns. However, because the sampling methods employed in the SGPA surveys vary across state and party (and year), care and caution are required in aggregating the individual state results into findings for the region as a whole. The analysis conducted here addresses this issue by first calculating unweighted individual state scores. Then, using the states as the unit of analysis, overall regional measures are calculated by averaging the state scores. The measure used to investigate the policy views of Democratic and Republican Party activists is the state mean scores for each available issue item. The analysis of intraparty differences employs the average state standard deviation scores for the different policy items included in the SGPA survey. The larger a standard deviation, the greater the level of division within the party.

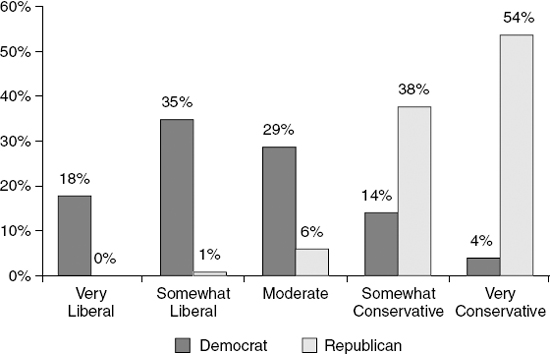

Figure 5.1 shows that there is a wide division, and relatively little overlap, in the self-described political ideology of southern Democratic and Republican Party activists. In 2001, most Democrats described their political beliefs as “very liberal” (18 percent) or “somewhat liberal” (35 percent). However, a substantial number—about one in five—of the Democratic activists identified themselves as either somewhat (14 percent) or very (4 percent) conservative.

Figure 5.1 Party Activist Ideology—2001.

In contrast, Republican Party activists in 2001 overwhelmingly and thoroughly described themselves as conservatives. Indeed, a majority (54 percent) of southern Republican activists said that they are very conservative. An additional 38 percent described themselves as somewhat conservative. An extremely small proportion of Republican activists identified themselves as moderates (6 percent) or liberals (1 percent).

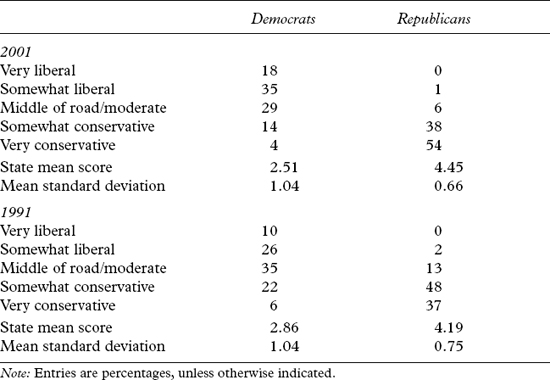

The results presented in table 5.1 also show that important changes have occurred in the self-described ideology of Democratic and Republican activists. In his analysis of the 1991 study, McGlennon (1998b, 87) reported that Democratic activists were found “completely across the ideological spectrum but tend to cluster in the middle, from ‘somewhat liberal’ to ‘moderate’ to ‘somewhat conservative.’ ” The 2001 study, however, shows that Democratic activists have generally become more liberal. In particular, the number of self-described liberals among Democrats increased from about 36 percent in 1991 to about 53 percent in 2001. While Democratic activists have shifted in the liberal direction, the standard deviation scores show that they remain about as ideologically heterogeneous as they were previously.

Table 5.1 Self-described Political Ideology among Party Activists, 2001 and 1991

At the same time Republican activists have become more conservative. However, this change is not the consequence of a decrease in the number of moderates or liberals within the party. In both 1991 and 2001 almost no Republican activists identified themselves as anything other than conservatives. What has changed is the distribution among conservatives. McGlennon (1998b, 87) found in the 1991 survey that there was a relatively even balance among Republican activists between those who said that they were “somewhat” conservative and those describing themselves as “very” conservative. Now, however, a majority of Republican activists say that they are “very” conservative. As a result of this change, Republican activists, while already more ideologically homogeneous than Democrats, have become even more so in 2001, as indicated by the standard deviation measure.

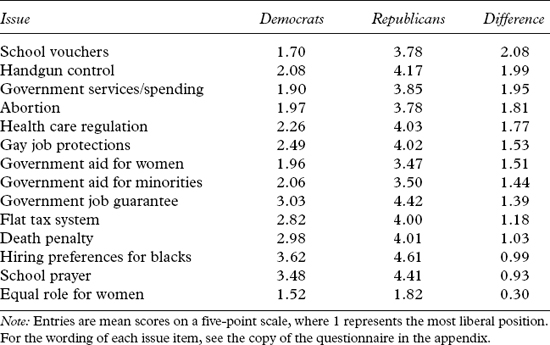

Democratic and Republican Party activists are expected to differ when it comes to political issues, and the results presented here support that belief. In particular, on each of the issues examined in the 2001 SGPA survey, Democrats are, on average, more liberal (or less conservative) than their Republican counterparts (table 5.2). Specifically, the typical Democrat is more likely than the typical Republican activist to favor public provision of social services, including health care and employment; women having an equal role with men in society; women’s right to an abortion; stricter gun control laws; the government working to improve the social and economic positions of women, blacks, and other minorities; laws protecting gays from job discrimination; and giving preferences to blacks in hiring and promotion decisions. Similarly, Democratic activists are more opposed than the typical Republican Party activists to school prayer, the death penalty, a flat tax, and school vouchers.

Table 5.2 Average State Mean Scores on Issues by Party, 2001

Further, the conservatism of the Republican activists extends beyond their being relatively more conservative than Democrats. Republican activists are also “absolutely” conservative in their opinions. Specifically, a conservative position (as indicated by a mean score greater than the scale’s midpoint of 3.0) is taken by Republican activists on all but one of the policy issues examined. This single exception involves the issue of whether “women should have an equal role with men in running business, industry, and government.” The issues that generate the highest level of conservatism among Republican activists involve preferential hiring and promotions for blacks, government responsibility to provide jobs and a good standard of living, and allowing prayer in public schools.

While consistently less conservative than their Republican counterparts, southern Democratic grassroots party activists are, on average, not uniformly liberal in their policy beliefs. On some issues, such as equality for women in society, school vouchers, the provision of social services, government efforts to “improve the social and economic situation for women,” and abortion, Democratic activists are generally liberal (i.e., have an average mean score of less than 3.0). However, on issues such as preferences for blacks in hiring and promotion decisions, school prayer, and a government of a good standard of living, Democratic activists express a more even mix of liberal and conservative views.

Table 5.2 also shows that several traditional “New Deal” social-welfare-type policy questions generate the largest difference in average issue opinions between Democratic and Republican activists. This reflects differences in partisan attitudes toward Depression era programs at that time, ranging from bank and stock market regulations to government work projects to provide employment. At the time, Democrats pushed for greater assistance by the federal government, while Republicans opposed such an expanded role and pushed for greater reliance on the free market. This divide still exists. Specifically, large gaps in opinions are found between the two groups of activists regarding issues such as school vouchers and the provision of social services and health care.

In recent decades new social issues involving lifestyle concerns such as gay rights, abortion, school prayer, and gun control have become the province of political disputes. There is, however, no consistent pattern regarding differences between the party activists on these issues. For two of the cultural issues—gun control and abortion—there are large differences in preferences between Democratic and Republican activists. Yet partisan differences are relatively small on issues such as whether women should have an equal role with men in society; school prayer; and, somewhat surprisingly, given the region’s political history, preferences for blacks in employment decisions (see chapter 3 for a more detailed discussion of the role of race). In the instance of equality of women and men, both groups fall on the liberal end of the scale; however, the issues of school prayer and employment preferences for blacks elicit more conservative responses from both Democrats and Republicans.

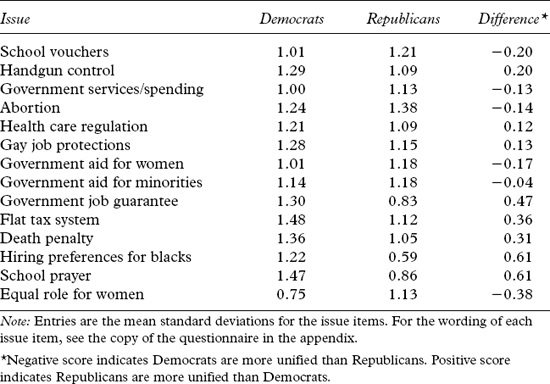

In terms of intraparty divisions, the results show that Democrats are most in agreement on the issues of women having an equal role with men in society, the provision of government services, school vouchers, and government working to improve the social and economic situation for women (table 5.3). Conversely, the level of agreement among Democrats is lowest on the flat tax and school prayer issues. Among Republicans, consensus is highest on the issues of black preferences in hiring and promotion decisions, a government guarantee of jobs, and school prayer. Abortion is the issue that most divides Republicans.

The results also show that on some issues Republican activists are more unified than Democrats. Republicans are especially united on the issues of a government guarantee of jobs and a good standard of living, school prayer, and whether preferences should be given to blacks. On each of these three concerns the Republican Party enjoys a considerable advantage in party unity. On other issues, however, Democrats enjoy the greater level of internal consensus. Specifically, Democrats are more unified (sometimes slightly) on four issues generally involving the role and size of government: school vouchers, provision of social services, assistance to women, and assistance to blacks. Democrats are also more internally united than Republicans on the issues of abortion and women having an equal role in society.

Table 5.3 Average State Standard Deviations on Issue Items by Party, 2001

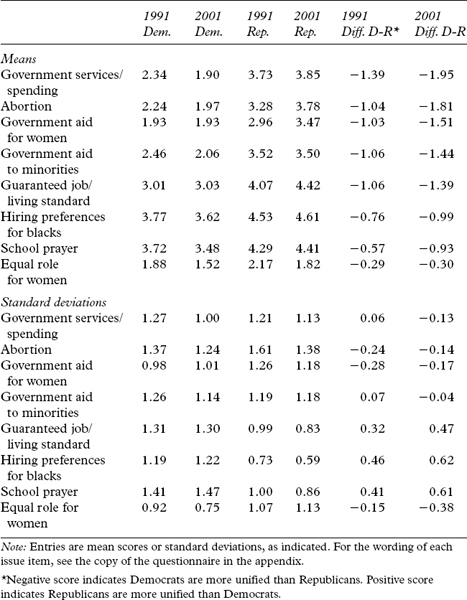

Eight of the specific issue items were asked in both the 1991 and 2001 SGPA surveys. Comparisons of the two surveys show overall that the two parties generally retained their relative issue positions, but the interparty gaps have grown while intraparty divisions have declined. Specifically, the opinions of Democratic activists have generally become more liberal (table 5.4). In particular, the level of support among Democrats has increased for government services, government efforts to improve the social and economic position of minorities, preferences for blacks in employment decisions, and women having an equal role with men in society. Similarly, Democrats have become more opposed to (though they still generally favor) school prayer. The typical Democrat, however, has not shifted position regarding the issues of a government guarantee of jobs or government efforts to improve the social and economic conditions of women.

Conversely, Republican activists have generally become more conservative in their issue positions. The one exception to this pattern of increased conservatism involves the issue of women having an equal role with men in society, where Republicans have shifted to a more liberal position in 2001 compared to 1991. Further examination of the standard deviations shows that the level of internal unity among Democrats has increased on some (government services, government assistance to blacks and other minorities, and abortion) but not all the issues examined. However, among Republican activists the level of internal consensus increased (though marginally on the government assistance to blacks and other minorities question) on each issue.

Overall, then, the results from the two surveys show that during the last decade Democratic activists have generally become more liberal while their Republican counterparts have become more strongly, and uniformly, conservative. The net result of these changes is that the two parties have become more polarized in terms of the policy preferences of their activists.4 In particular, on each of the issues examined, the differences between the two groups of party activists are larger in 2001 than they were in 1991. It might be expected that differences should be sharpest on economic issues and less on social issues, but there is no clear differentiation. While the economic issue divisions arising out of the New Deal continue to be a factor, newer social issues also provide a line of division. However, there is no consistent pattern. On some issues, such as equal role for women, the gap between the parties increased by only a small amount. On other issues, such as abortion and government services, the polarization between the parties increased by a substantial amount.

Table 5.4 Means and Standard Deviations on Issue Positions among Party Activists by Party, 1991 and 2001

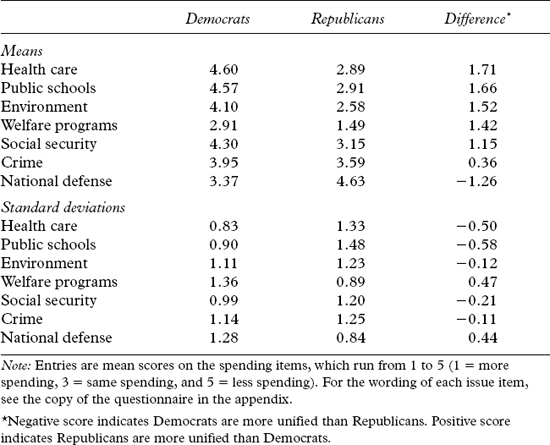

Partisan differences are also found when Democratic and Republican activists are asked about federal spending (table 5.5). Democratic Party activists are more likely than Republicans to favor increased federal spending on health care, public school, social security, environmental protection, crime, and welfare. Republicans are more in favor of increased spending for national defense than are Democrats.

Table 5.5 Average State Mean Scores and Standard Deviations on Spending Issues by Party

Among Democrats, the highest level of support for increased spending is found in the areas of health care and education. Neither group of activists supports increased spending for welfare programs. Besides lowering federal financial support for welfare, Republican activists are most likely to favor lower federal spending for environment protection and health care. Further, the largest partisan gaps in spending preferences are found in the areas of health care, education, and protecting the environment. In these policy arenas, most Democrats favor higher spending while most Republican activists lean toward reduced spending. The smallest partisan difference in spending preferences was found when respondents were asked about the crime issue. Here, both Democratic and Republican activists express mixed feelings about whether federal spending should be increased or decreased.

The standard deviations show that, when asked about federal government spending, Democrats are generally more unified in their opinions than are Republicans. This is particularly the case with regard to spending in traditional “New Deal” policy areas such as education, health care, and social security. The level of consensus among Republican activists is higher than is the case among Democrats regarding federal spending for national defense and welfare programs.

Many of the most important elections within the South—for president, U.S. senators, and governor—occur at the state rather than the regional level. Further, while similarities among southern states are to be expected, there is no reason to assume that each state’s party system is a carbon copy of the others. Thus, understanding political conflict within the region requires, in addition to a regionwide analysis, separate investigations of the policy views of party activists within each of the eleven former Confederate states. Conducting a detailed state-based analysis is, unfortunately, beyond the scope of both this chapter and volume as a whole. Still, a limited analysis of the self-described political ideologies of each southern state’s party activists provides some information about this important topic (see Clark and Prysby 2003 for more extended discussions of individual states).

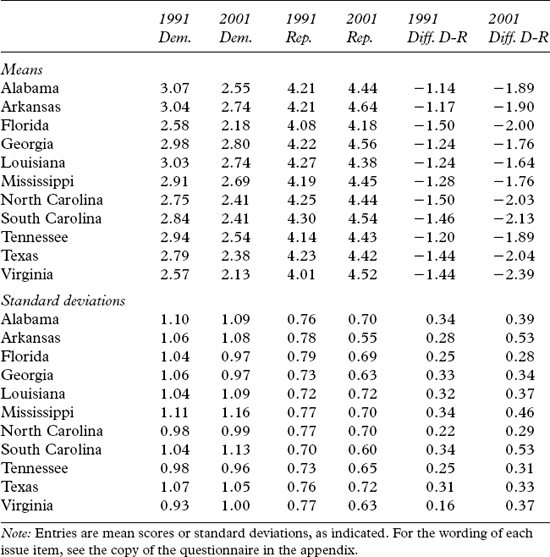

The results shown in table 5.6 show that between 1991 and 2001 Democratic activists in each southern state became more liberal. In seven of the states (Alabama, Florida, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Texas, and Virginia) a majority of the 2001 Democratic activists label themselves as very or somewhat liberal (results not shown). In three of the remaining states (Arkansas, Louisiana, and Tennessee), liberals constitute more than 40 percent of the Democratic activists. Only in Georgia are less than 40 percent of Democratic activists self-described liberals.5 Conversely, the number of conservatives among Democratic activists declined between 1991 and 2001 in each state examined. Finally, the results show that in 2001 the most “liberal” Democratic Party organizations in the South are found in Virginia and Florida, while the least liberal party organizations exist in Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, and Georgia.

Within each of the region’s states, Republican activists have moved in the opposite ideological direction. In every southern state except Florida, a majority of the 2001 Republican activists say that they are “very” conservative. In three of the states—Arkansas (67 percent), Georgia (63 percent) and South Carolina (60 percent)—at least six in ten Republican activists describe themselves this way. Even in Florida, the number of self-described conservatives among Republican activists increased between 1991 and 2001.

The net result of these changes is that in each southern state, the two parties have become more polarized in terms of the self-described ideologies of their activists. The two parties are most polarized in Florida, North Carolina, Texas, South Carolina, and Virginia. The smallest partisan ideological difference among activists is found in Louisiana.

Table 5.6 Mean and Standard Deviation for Self-described Political Ideology among Party Activists by State, 1991 and 2001

The reason states vary in the ideological polarization of party activists is not altogether clear. It could be that repeatedly experiencing highly competitive, and sometimes acrimonious, political campaigns results in the increasing polarization of Democratic and Republican activists. Alternatively, states may vary in the degree to which activists have completed the process of sorting themselves ideologically into the “proper” party.

The location and magnitude of the policy differences existing between and among Democratic and Republican Party activists are important aspects of the political conflict occurring in the South. Overall, the results of the SGPA surveys show that there are many areas of partisan policy differences, and these gaps between Democrats and Republicans are often wide. Specifically, the results show that the two sets of activists are quite different in their self-described ideology. Democratic activists generally identify themselves as somewhat or very liberal, while a majority of southern Republican activists label themselves as very conservative. The results further show that, in terms of self-described ideology, the two parties have become more polarized.

The results of the SGPA surveys also show that Democratic and Republican activists hold distinct opinions on a variety of important political issues. Specifically, southern Democratic activists are consistently more liberal in their views than are their Republican counterparts. Additionally, Democratic and Republican activists often hold widely different opinions concerning government spending—especially in traditional “New Deal” policy areas such as health care, education, and social security. Moreover, neither party has a consistent advantage in intraparty unity. There are suggestions, however, that both groups, especially Republicans, are becoming more internally unified. Further, comparing the results of the 1991 and 2001 SGPA studies shows that, overall, southern Democratic and Republican Party activists have become increasingly distinct in their issue positions. Southern Democrats have become more liberal while southern Republicans have become more conservative. Finally, the analysis shows that this pattern of increased policy polarization has occurred within each of the southern states. Variations, however, are found across states in the degree to which the parties have grown apart. The reasons for these state level differences remain an important question for future examination.

Altogether, the ideological and issue divisions currently existing between southern Democratic and Republican activists suggest that future election campaigns within the region will typically involve candidates offering voters starkly different ideas and choices regarding a variety of social, economic, and political policy concerns. As a result, the voters attracted to a party are also likely to hold distinctive policy views. Further, Democratic and Republican Party members are likely to follow distinctly separate issue agendas when elected to public office. Greater polarization may also lead to much more bitter struggles over the direction of government policy. Finally, the substantial—and growing—policy and ideological differences found between the two groups of southern party activists confirm the belief that a lack of issues no longer characterizes the region’s politics. Rather, issues now have quite a bit “to do with it.”

1. For discussions of partisan changes in the South, see for example, Aistrup 1996; Beck 1977; Black and Black 1987, 1992; Campbell 1977a, 1977b; Glaser 1996; and Lamis 1988. For research examining the general topic of party system change, see, for example, Carmines and Stimson 1989; Key 1967; MacDonald and Rabinowitz 1987; Marchant-Shapiro and Patterson 1995; Miller and Schofield 2003; and Schattschneider 1960.

2. For earlier studies of activists’ policy opinions see McClosky, Hoffman, and O’Hara 1960; Nie, Verba, and Petrocik 1976; Montjoy, Shaffer, and Weber 1980; Jackson, Brown, and Bositis 1982; Kirkpatrick 1976; Miller and Jennings 1986; Moreland 1990a; Brodsky and Cotter 1998.

3. See the discussion in chapter 8 concerning why the spending items are not easily placed on a liberal-conservative continuum.

4. These results demonstrate that the region’s parties have participated in the national trend toward increasingly polarized parties. For recent studies showing this increased polarization, see Abramowitz and Saunders 1998; Hetherington 2001; and Layman and Carsey 2002.

5. See the methodological appendix to this volume for a discussion of the Georgia sample.