Observers of political parties often speak of “the party” as if it were a monolith, an organization that operated with a singular purpose. The reality is much different, at least in the American context, where the Democratic and Republican Parties are characterized by a remarkable level of decentralization (Epstein 1986). Individual party organizations may be strongest when they have a considerable degree of autonomy, but the party as a whole gains strength from cooperation among its constituent parts (Schlesinger 1985). Thus, we seek to examine the level of interaction between local party activists. Using contact between grassroots activists and other party and elected officials as a proxy for integration, we find that activists who are in frequent contact with other party leaders are more active and feel more connected to their party than those who have little contact. Those who are better integrated also are more likely to perceive that their organization is gaining in strength.

The relative levels of autonomy and cooperation between levels of U.S. parties have been categorized in very different ways by parties scholars. Eldersveld (1964) found low levels of contact between local party activists in the Detroit area. He termed this phenomenon “stratarchy” to emphasize the autonomy of the various levels (or strata) of the party. Unlike hierarchical organizations where control is administered from the top down, party leaders in Eldersveld’s study seemed to have little control over—or even knowledge of—the workings of other organizational groupings.

An alternative perspective is offered by Joseph Schlesinger (1985). He conceptualized the various units of a party as nuclei. Though independent, various nuclei should agree to cooperate when their interests are threatened. Multinuclear parties are able to take advantage of economies of scale in their campaign activities. Since support generated for one of the party’s candidates would likely spill over onto other candidates’ campaigns, all can benefit from their cooperation with one another. Of course, in doing so some level of autonomy must be sacrificed. High levels of uncertainty over election outcomes would encourage multinuclear organizations to form, while various nuclei could retain their autonomy when the likelihood that they would win or lose was known.

The evidence available to test these competing theories suggests that parties have become increasingly centralized, and perhaps increasingly integrated, over time. Democratic centralization in the 1970s focused on the rules of the presidential nominating process, while Republicans opted to strengthen their national organization by making funds available to state and local organizations (Bibby 1981; Wekkin 1985). This latter approach was especially conducive to integration, as the financial rewards were often tied to party building activities that lent themselves to greater cooperation across organizations. Huckshorn and his colleagues (1986) found a relationship between state-national integration and state party organizational strength, which they attributed to the socialization of state party leaders more than the availability of resources for party building itself.

There is evidence of cooperation across party units within states, as well. The availability of “soft money” encouraged state parties to engage in such activities like fund-raising, computing services, and voter mobilization (Bibby 1999a, 72–75). For example, the frequency of joint registration drives and get-out-the-vote efforts increased dramatically in the early 1980s (Gibson, Frendreis, and Vertz 1989). More recently, local parties began to work more closely with individual candidates to provide campaign labor and sophisticated technologies (Frendreis and Gitelson 1999). In contrast to the stratarchy observed by Eldersveld, Schwartz (1990) described the level of integration among Illinois Republicans as a “robust” network of party leaders, elected officials, candidates, and affiliated interest groups.

Previous researchers conceptualized integration as “a two-way pattern of interaction” between party units (Huckshorn et al. 1986, 978). The successful integration of disparate party units into a single, cohesive party requires at minimum communication between those units. For our purposes, the degree of this communication will be assessed by how often the county chairs and precinct committee members communicate with a range of other partisan figures. Greater communication frequency is, then, taken as an indicator of greater integration. The respondents were asked the following:

Now we would like to ask you about your communication in the party organization. How often do you communicate with:

county party chair?

other county party members?

state party chair?

state party committee members?

national committee members?

local government officials?

state government officials?

national government officials?

The responses included “very often,” “often,” “seldom,” and “never.” While frequent communication may not guarantee meaningful integration, a lack of contact between party units would ensure a lack of integration.

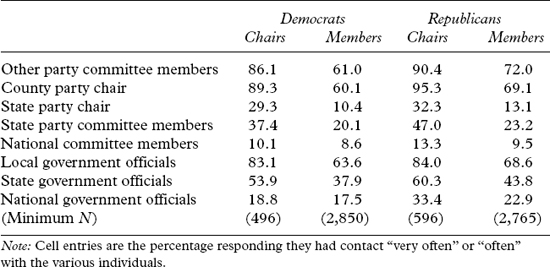

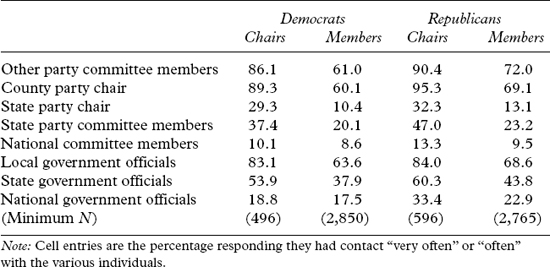

The basic responses to this battery of questions is shown in table 12.1. Respondents are broken down by party and position. The entries in the table are the percentage of respondents who say they communicate “very often” or “often” with their fellow party officials, as well as elected officials. Four clear patterns are present in this table. First, the county chairs of each party report higher levels of communication than do precinct committee members on every single question (see also Clark and Lockerbie 1993; Brodsky and Brodsky 1998). While this is not surprising (a chair that does not communicate would be an ineffective party leader), the magnitude of the differences is substantial. In both the Democratic and Republican cases, the difference between the mean for chairs and members is just over sixteen points. Second, Republican chairs report higher levels of communication than do Democratic chairs. On each of the eight communication items, Republican chairs have more reported contact. The mean response for Republican chairs is six points higher than that of the Democratic chairs. Third, on every question, Republican precinct committee members report more frequent communication than do their Democratic counterparts. The difference between the mean response for the two sets of committee members is 5.4. Fourth, the level of communication that takes places decreases as the partner in communication grows less proximate to the local level. The highest levels of communication are with other party committee members and county party chairs, with contact rates dropping sharply as the scope is broadened to the state party committee, the state chair, and national committee members. Likewise, contact with elected officials is highest at the local level and lowest at the national level.

Table 12.1 Levels of Contact by County Chairs and Precinct Members

When compared to 1991, these results reflect the increasing success of Republican candidates for local, state, and national offices across the South. At the time of the original SGPA study, Democratic leaders were much more likely to report contact with local and state government officials (Clark and Lockerbie 1993). Ten years later, Republicans had pulled even at the local level and surpassed the Democrats in contact with national government officials. Democrats, meanwhile, reported lower levels of contact with elected officials at all three levels compared to the earlier study.

To facilitate analysis across the remainder of this chapter, we have created an index of integration by adding the eight communication terms.1 Responses to the eight questions were simply reversed to make high scores represent high integration, and then summed. The resulting scale runs from 8 (no contact at all) to 32 (“very often” in contact with all party units).

In the analysis that follows, the index was broken into thirds and activists were grouped accordingly to facilitate comparisons: low integration (8–15), moderate integration (16–24), and high integration (25–32). Among chairs, 18 percent of the Democrats were scored as highly integrated, with 21 percent of the Republicans being scored that way.2 Approximately 11 percent of the Democratic chairs and 5 percent of the Republican chairs were scored as having low integration. Among precinct committee members, 7 percent of the Democrats and 9 percent of the Republicans were highly integrated, with 34 percent of the Democrats and 26 percent of the Republicans being scored as having low levels of integration. Figure 12.1 displays the relative size of each group.

While the web of effects that may exist around a fully integrated party are likely complex, identification of all effects is impossible. What we can expect to find is that grassroots activists working in a highly integrated environment will possess a different set of psychological perspectives than found among activists working in an environment with low levels of integration. We thus compare those activists falling into the high and low integration categories across a range of items. We first look at the length of time they were active in politics and whether they had held office. We then examine their activity in various elections, their attitudes toward the party, and their perceptions of the strength of their organizations.

Figure 12.1 Levels of Party Integration by Party and Position.

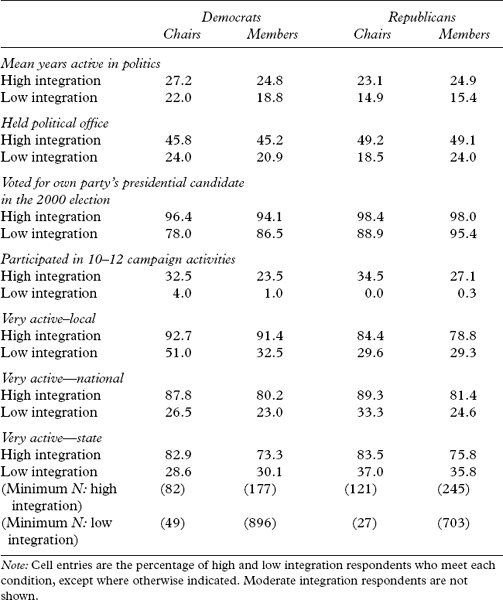

The survey instrument did not include large numbers of attitudinal measures. It did contain a battery of questions on party-related behavior, however, which we can safely assume would be, at least in part, influenced by a respondent’s psychological standing in politics. Table 12.2 reports analysis on a range of political activities that should reflect the strength of attitudes among chairs and members. In terms of length of political activity, Democrats have a longer history than do Republicans (22.1 versus 19.3 years), and the county chairs of each party have longer average histories than do precinct committee members of that party (23.7 versus 20.4 for Democrats, 21.8 versus 19.1 for Republicans). Additional differences are found when these groups are broken down by levels of integration (the first set of numbers in table 12.2). Activists classified as having high integration have longer histories of activity, in some cases by sizable amounts. These same basic patterns hold across the range of activities listed in the table. There is no consistent pattern of difference between the two partisan groups, but chairs tend to be more active than members. Lower integration levels are also linked to sometimes dramatically lower activity rates. This is true for the respondents’ history of office holding, level of campaign activity, and general activity in local, state, and national politics. The impact of integration extends to support for the parties’ presidential candidates. Those with low integration were more likely to defect from their party’s ticket, although the difference among Republican precinct members was quite small.

Table 12.2 Political Activity and Party Integration

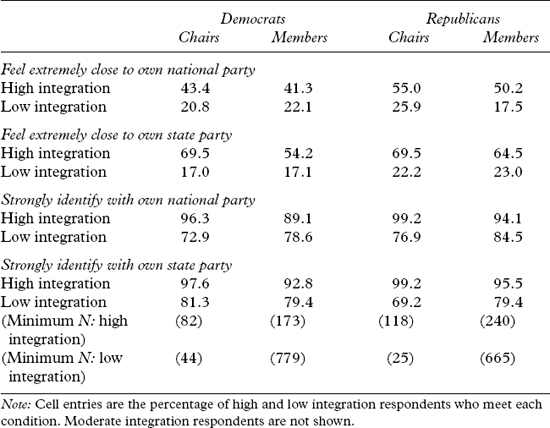

One set of party-specific attitudes we can assess within the context of integration involves partisanship and the degree to which the activists feel “close” to their party. Responses to four questions of this sort are shown in table 12.3. The first two questions deal with how close respondents feel to their national and state party. The entries in the table are the percentage who indicate they feel “extremely close” to the party in question. A couple of clear patterns are obvious. First, county chairs generally are more likely to feel extremely close to the party than are precinct committee members. Second, high integration respondents are far more likely to feel close to their party than are low integration respondents from the same party and position group. Third, an interesting reversal appears when comparing how each party-position-integration level group feels about their state and national parties. High integration respondents in all four groups are more likely to feel close to the state party, while low integration respondents are more likely to feel close to the national party (albeit with both rates lower than their high integration counterparts).

Table 12.3 Party Attitudes and Party Integration

The next two questions in the table are concerned with partisan intensity. The first observation to make is that all groups are clearly partisan. This is not unexpected since they were, after all, surveyed because of their party activity. Still, the level of partisanship is impressive. Among high integration respondents, the weakest set is the pool of Democratic precinct committee members, where only 89 percent are strong partisans in state politics. Among low integration respondents, the low mark is among Republican county chairs, with 69 percent reporting a strong partisan attachment to the state party. There is a slight likelihood for chairs to be more partisan than committee members and for high integration respondents to be more strongly partisan than low integration respondents. Also, Democratic respondents have a slight tendency to be more strongly attached to their state party, while Republicans report stronger attachments to their national party. While this difference may seem surprising in the light of the Republican Party’s emphasis on state party building, it does seem perfectly compatible with the nature of politics in the South (see chapter 6; Clark and Lockerbie 1998). Local Democratic activists who have seen their political fortunes fade a bit may blame the decidedly nonsouthern agenda of the national party and its candidates. In contrast, many of the Republican activists may feel that their local situation has been improved by the rising tide of the national party. Unfortunately, there is no appropriate question in the survey that would allow us to directly test this plausible notion.

Another way to examine the relationship between integration and partisan attitudes is to explore the relative levels of purism and pragmatism among these grassroots activists (see chapter 9). Here, we simply replicate Prysby’s measure of purism and consider it through the lens of party integration. Among Democrats, for both county chairs and committee members, those respondents who report the highest integration hold decidedly more pragmatic views. Those activists who are the most likely to value ideological purity over winning are the least likely to have communication with other elements of the party. The same is true for Republican committee members, but there is only a very slight difference between high and low integration Republican chairs. While an individual’s view on the winning at all costs versus ideological purity trade-off is certainly not the only factor that shapes integration, it seems likely that an ideological purist is less likely to engage in communication and collaborative party work with a fellow partisan with whom there may be ideological disagreement. Indeed, perhaps the ideal local party leader is one that ranks party success as the primary goal, with any specific ideological or issue agenda falling somewhere down the list.

Consistent with the evidence presented so far, we would expect a relationship between the degree to which respondents report integration in the party and their views of the strength of their respective party. Others (e.g., Cotter et al. 1984) have shown a relationship between the organizational strength of the party and level of integration. While we do not have a full measure of organizational strength, we do have the activists’ subjective assessments of how strong their party is on a variety of fronts, relative to their organization’s strength ten years previously. That is to say, we have a measure of perceived change in party organizational strength. We expect that more highly integrated respondents will be more likely to feel positive about the changes in their party. We theorize that the central mechanism for this is the psychological effect of communication. All things equal, an activist that is in regular contact with other party officials is more likely to catch a sense of a dynamic party than is one who is in less frequent contact with others.

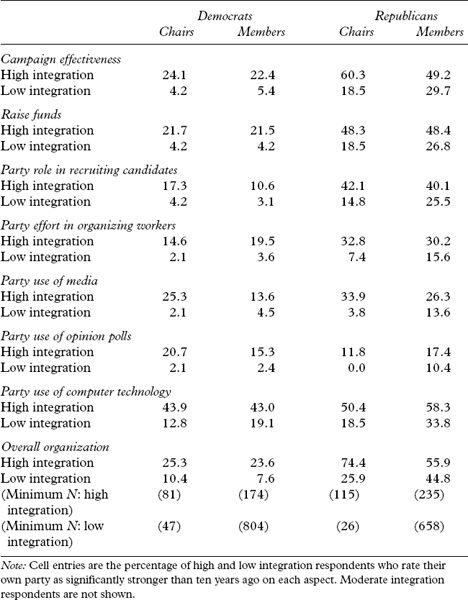

Respondents were asked to assess the strength of their party today, relative to ten years ago, in seven specific areas, as well as in terms of overall organization. The most dramatic results are in terms of integration (see table 12.4). Of the thirty-two possible within party-position comparisons in the table, respondents with higher levels of integration report their party as being significantly stronger more often than respondents with low levels of integration in all thirty-two. The differences are significant; in some instances the high integration response is ten times the low integration response. Clearly, respondents who are in more frequent contact with other party and elected officials are the most glowing in assessment of their party’s strength. Several other trends are worthy of note. First, there is no systematic pattern of differences between county chairs and precinct committee members. There seems to be nothing in the role of county chair that colors the respondents’ views in a unique way. Second, Republican activists are more likely to report their party being significantly stronger than are their Democratic counterparts in similar positions with similar integration. These partisan differences are not trivial. Indeed, in numerous cases the percentage of Republicans indicating significant growth is more than twice the percentage of Democratic respondents who do so. This is true for overall organization, as well as for six of the seven specific areas considered. In one, the party’s use of public opinion polls, the Republican activists have unusually weak assessments of their party. While the differences by party are interesting, they are also expected. The ten-year period under consideration covers a time in which the Republican Party matured as an organization in the South. It would be surprising if Republicans did not see greater increases in strength than did the Democrats.

Table 12.4 Assessments of Party Strength and Party Integration

Table 12.5 Electoral Competitiveness and Party Integration

Assuming that parties demonstrate any strategic behavior, the degree to which different party elements are integrated should not be a random feature of the southern party system. Activists in hotly contested areas and those representing strong concentrations of the core constituency are more likely to be involved in active communication channels than are those who are a lost cause geographically (Schlesinger 1985; Trish 1994). While ascertaining the strategic intent of party communication is beyond our data, we do have an indirect method of tapping this possibility. We can use the Democratic vote share for president as a measure of the importance of the county to the party. The stronger the Democratic vote, the more integration we would expect among Democrats, with Republicans in the strongest Democratic locales being less likely to report high integration.

The results, shown in table 12.5, confirm these expectations.3 Among Democrats, stronger support for Clinton (1992, 1996) and Gore (2000) is found among the high integration respondents, especially the chairs. Among Republicans, the reverse is true, with the Republican chairs reporting high levels of integration having the lowest levels of Democratic support (there is no difference among Republican committee members). While this is admittedly indirect evidence, it does suggest that parties do not “waste” communication efforts on activists in areas where the party has lower odds of success, or, alternatively, activists in counties where the odds of success are low may feel less need to be integrated.

Our analysis of communication patterns among southern grassroots party activists provides a first look at party integration within the region. Several findings are worth noting. First, Republican contact with elected officials increased over the decade of the 1990s, while Democratic contact decreased. This trend may reflect the success of Republican candidates across a wide range of elections. It may also exemplify the difficulty the Democrats have had in maintaining their multiracial, ideologically heterogeneous coalition in elections and in the party organization itself.

Second, levels of integration are related to a variety of behaviors and attitudes. Activists with higher levels of integration are more active in campaigns, feel closer to the party, and are more likely to believe that their party has gained strength.

Finally, there is a modest connection between the success of a party’s presidential candidates and the integration of its activists. This relationship may reflect a strategic calculation on the part of party leaders. Alternatively, some activists may be energized by a particular candidate or campaign, leading them to become more involved in the party’s affairs (Trish 1994).

Taken together, these results demonstrate the need to reexamine the traditional notion of U.S. party organizations as decentralized and largely autonomous from one another. County party chairs have considerable contact with those lower in the hierarchy, with other chairs, and with local elected officials. Paired with polarization in terms of ideology and issues (see chapter 5), a new type of party organization may be evolving in the South.

1. One might question whether all the contact items fall along a single dimension. To answer this question, the responses were subjected to factor analysis. When all respondents are analyzed together, two distinct factors are apparent. The first, a “local politics” factor, includes communication with county party chairs, other precinct committee members, and local elected officials. The second factor is best considered a “state-national politics” factor. Items loading primarily on this factor include communication with the state party chair, members of the state party committee, members of the national party committee, and state and national elected officials. The two factors, correlated at 0.46, combine to explain about 65 percent of the variance, with the nonlocal factor alone explaining 50 percent. We believe that combining them into a single scale is consistent with the broader focus on integration. The notion of meaningful integration requires communication across a full range of partisan entities. All things equal, more frequent communication—be it with elected officials, state party committee members, or other precinct committee members—means a greater likelihood of integrated party units. Analysis constraining the results to a single factor shows all terms have a substantial loading on the factor, and the model fit is consistent across the four party-position groups.

2. This represents a switch from the 1991 Southern Grassroots survey, which found Democratic chairs as having higher levels of integration. Clark and Lockerbie (1993) ranked 30 percent of the Democratic chairs as highly integrated, as were 25 percent of the Republican chairs. Only 4 percent of the Democratic chairs and 7 percent of the Republican chairs were scored as low. Among precinct members of both parties, less than one in ten were in the high integration range, while a third scored in the low integration category.

3. There is substantial variation in the Democratic vote in the counties that are represented in our surveys, with a high of 85 percent and a low of 13 percent. According to ANOVA analysis, the mean levels of Democratic presidential support are significantly different for the party-position-integration level combinations (F = 28.19).