The American South has long made for a fascinating case study for the examinations of the causes and consequences of changes in the underlying distribution of partisan attachments. Once a region where the overwhelming majority held Democratic Party identifications (Key 1949), the South at the beginning of the twenty-first century is now divided between Democratic and Republican identifiers. Indeed, when the focus shifts just to southern whites, a majority now hold Republican Party identifications (Black and Black 2002). This partisan transformation occurred gradually, resembling what Key (1959) referred to as a secular realignment.

One major explanation for the slow pace of changes in partisan identifications emphasizes the notion of split- or dual-party identification—that is, holding identification with different parties at the state and national level. The notion of different partisan identifications at multiple levels was introduced by Jennings and Niemi (1966) and applied to the South by Converse (1966), although the latter found little evidence to suggest that southern whites held split-party identifications. However, as scholars began to question the dimensionality of the traditional measure of partisanship (Petrocik 1987; Katz 1979; Valentine and Van Wingen 1980; Weisberg 1980) and as the notion of multiple levels of partisanship appeared applicable in other federal political systems, most notably Canada (LeDuc, Clarke, Jenson, and Pammett 1984), there was renewed interest, both in the South and at the national level, in the concept of dual or multiple partisanship (Hadley 1985; Niemi, Wright, and Powell 1987; Wekkin 1991; Barth 1992). The concept appeared especially appropriate to the study of southern partisanship, given the high incidence of split-ticket voting in the region (Hadley and Howell 1980). Applying the notion of split partisanship to party activists in the South, Clark and Lockerbie (1998) found that identification with different parties at different levels (or differing strength of partisanship at different levels) was most evident among Democratic activists, who increasingly eschewed national Democratic identification due to the perceived liberal drift of the party, but who continued to find the party acceptable at the state and local levels. However, among Republicans there was also evidence to suggest greater attachments to the national party than to the state party. This may reflect the weak Republican Party organization at the grassroots level as well as the emphasis placed by southern Republicans on a “top-down” strategy (Aistrup 1996).

A focus on party attachments utilizing data from the 2001 SGPA is important for two reasons. First, the 1990s produced a culmination of the realignment among southern whites that had been developing for decades (Black and Black 2002; Lamis 1999). A Republican advantage at the presidential level along with continuing Democratic success at the state and local level had characterized party competition in the post–Voting Rights South (Black and Black 1987, 1992; Petrocik 1987; Swansbrough and Brodsky 1988; Stanley 1988; Lamis 1990; Glaser 1996). However, in the 1990s, southern whites increasingly brought their subpresidential voting behavior and party identifications into line with their presidential vote choice (Black and Black 2002). Indeed, the South is now witnessing some of its most partisan voting patterns in elections below the presidency (Knuckey 2000; Prysby 2000; Shaffer, Pierce, and Kohnke 2000; Bullock, Gaddie, and Hoffman 2002). Second, a focus on the party attachments of activists is important as it is likely to provide some insights into future party competition in the region. Carmines and Stimson (1989) argue that realignment is first evident at the elite level before moving downward to the mass level. At the same time, party activists provide a cadre of potential candidates for elected office. Thus, an examination of party attachments of activists ought to provide a reflection of the partisan upheavals of the 1990s, as well as providing some indicators about the potential for further realignment, the nature of party competition, and the coalitional bases of party support in the region.

Scholars have examined party attachments in different ways. One approach has been to focus on split or dual partisanship by examining the partisan identifications at the national and state levels (Hadley 1985; Clark and Lockerbie 1998). On the other hand, Steed and Bowman (1998) refined this concept to focus on the strength of party attachment based on responses to both the national and state party identification as well as items measuring affective feelings toward the national and state parties. As the overwhelming majority of party activists held consistent party identifications based on the first measure (85 percent of Democrats and 90 percent of Republicans),1 the more inclusive measure of strength of party attachment is used here.

Following Steed and Bowman (1998), activists in each party were placed into three groups based on their strength of party attachments: consistently strong, mixed, and consistently weak. The consistently strong are those who held strong identifications with both their national and state parties,2 and said they felt very close to both national and state parties. Very close was defined as positions “1” and “2” on a seven-point scale (1 being “extremely close” and 7 “extremely distant”). The consistently weak are those who did not hold strong identifications with both their national and state parties and did not feel very close to both their national and state parties (positions 3 through 7 on the seven-point scale). The mixed category includes any other combinations of responses on the four partisan variables, that is, one, two, or three inconsistent responses to these items.

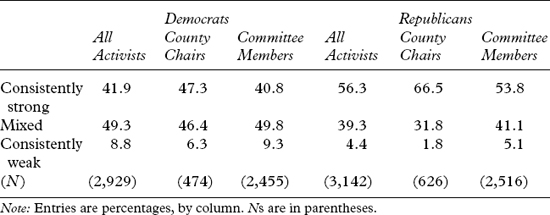

The distributions of these categories for each set of party activists are presented in table 6.1, which also disaggregates by party position (county committee chair or member). Among both sets of party activists, fewer than 10 percent hold consistently weak party attachments, a reflection of the more partisan environment in southern politics since the 1990s. Compared to the percentages reported by Steed and Bowman (1998, 186) using the original SGPA data, the number of Democratic activists holding weak attachments almost halved (15 percent in 1991), while the number of Republicans with weak attachments also declined, although in 1991 there were already few Republicans with weak attachments (7 percent). As in 1991, a majority of Republican activists held consistently strong attachments. While the proportion of Democrats with strong attachments has increased over the past decade, a plurality hold mixed attachments, as in 1991. Thus, it is the Republicans who appear to possess the most committed base of activist support. Disaggregating by party position reveals, as one would expect, that chairs in both parties are more likely to possess consistently strong attachments than members, with Republican chairs exhibiting the strongest attachments and Democratic committee members the weakest attachments. These patterns broadly held across each state, although some variation did exist. Among Democrats, Tennessee and Texas had the highest incidence of consistently strong attachments (47 percent in each case), while Louisiana and Mississippi had the lowest incidence of consistently strong attachments (33 percent in each case). There was more variation among Republicans, the consistently strong being most numerous in Arkansas (74 percent) and least numerous in Florida (46 percent).3

Table 6.1 Strength of Party Attachment among Local Party Activists

Having identified variation across each category of strength of party attachment, the chapter pursues three broad questions. First, are personal and political background characteristics of party activists systematically related to strength of party attachment? In addressing this question it is hoped that one might identify the cleavages that contribute to variations in party attachments. Second, to what extent do different degrees of party attachment affect the political behavior and nature and degree of participation by party activists? Third, how does the strength of party attachments affect orientations of activists toward the party organizational norms? The specific focus here is on purist-pragmatic orientations, patterns of communication with the party hierarchy, and the perceptions and sources of internal party factionalism. In addressing each of these questions, consideration will be given to the extent to which differences appear among Democratic and Republican activists by degrees of party attachment.

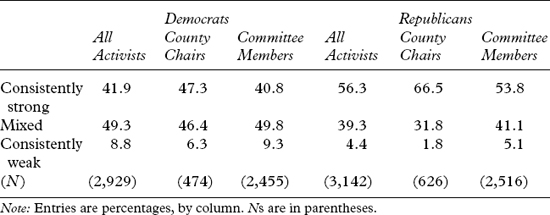

In examining personal characteristics that correlate with strength of party attachment, the assumption made is that members of groups most closely tied to the party electorally will exhibit somewhat stronger party attachments. Additionally, the analysis will allow one to discern the extent to which social group cleavages are evident, both between and within the parties at the elite level. Table 6.2 shows that there appears to be little variation in levels of party attachments caused by socioeconomic characteristics such as income and education for either set of party activists. At the same time, strength of party attachment seems to vary little based on whether a respondent is a native southerner or an in-migrant. Racial divisions have existed as a potential source of division within the Democratic Party, as discussed in more detail in chapter 3. Although white Democratic activists are slightly less prone to possess strong party attachments, racial differences across each category of party attachments appear less salient than a decade ago, again possibly because those whites with the weakest attachments are either no longer active in the party organization or have realigned and become Republicans. Among Republicans, blacks were slightly more likely to hold consistently weak attachments, but black Republican activists are so few in number that the difference in percentages is too small to be meaningful.

Table 6.2 Selected Personal Background Characteristics of Local Party Activists by Strength of Party Attachment

The gender gap has been especially visible in the South, primarily as a result of white southern men becoming more Republican in their party identifications at a more rapid rate than white southern women (Miller and Shanks 1996, 143; Norrander 1999; Black and Black 2002, 251–254). It appears that there is something of a gender gap at the elite level, too, with male Democratic activists being more numerous among those with consistently weak party attachments. In contrast, men and women are more evenly divided in the other two categories, especially among those with consistently strong attachments.

Surprisingly, age does not appear to be systematically related to strength of party attachment. According to the sociopsychological model (Campbell et al. 1960; Miller and Shanks 1996), party attachments should increase in intensity over the lifecycle. However, this pattern is only mildly evident among Republican activists, with the consistently weak tending to be younger than the other two categories, although even then only 30 percent of those with consistently weak attachments are under the age of forty.

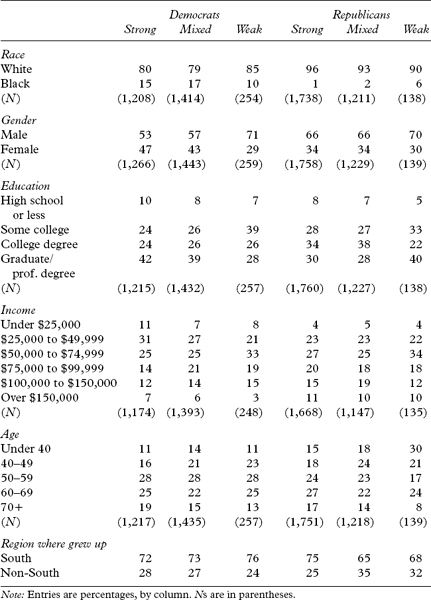

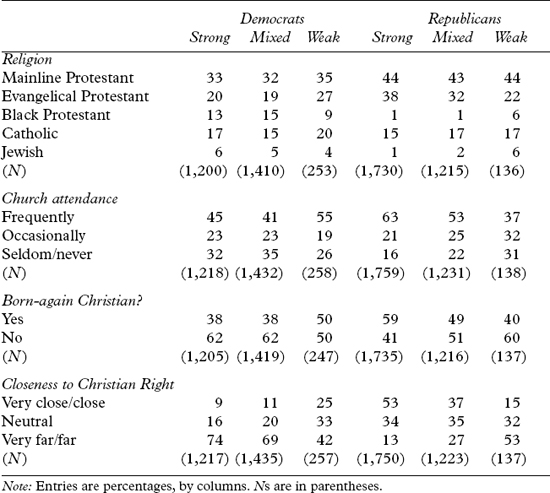

Table 6.3 presents several items concerning religion and religiosity. The items that appear to affect strength of party attachment among both sets of activists are religiosity and orientations toward the Christian Right. The rise of the “Christian Right” in southern state and local Republican Party organizations has been widely discussed, with many arguing that religiosity has emerged as an important interparty as well as intraparty cleavage (Green et al. 2002; Green, Rozell, and Wilcox 2003; Wilcox 2000; Baker, Steed, and Moreland 1998; Schneider 1998; Smith 1997; Oldfield 1996a). Moreover, this has increasingly been evident at the elite level, as discussed in chapter 2. It should be stressed that denominational differences do not appear to be important correlates of party attachment, with similar distributions across each major denomination in each category of party attachment. However, when examining frequency of church attendance, a pattern does appear. Among Democratic activists, the consistently weak tend to be more likely to be frequent church attenders than those in the consistently strong or the mixed categories; indeed, a majority of the weakly attached (55 percent) report attending church frequently, that is, once a week or more often. In contrast, among Republican activists, frequent church attenders tend to be more numerous among the consistently strong than among the mixed category and especially the consistently weak. Indeed, a minority of Republicans with consistently weak attachments (37 percent) are frequent church attenders.

Table 6.3 Religion and Religiosity of Local Party Activists by Strength of Party Attachment

A similar pattern appears when considering whether a respondent considered himself or herself to be a “born-again” Christian, as well as when considering general feelings toward the Christian Right. For example, among Democratic activists, only 38 percent of both the consistently strong and mixed categories consider themselves “born-again” Christians, whereas half of those with consistently weak attachments do so. Among Republicans the percentage that consider themselves “born-again” Christians increases with strength of party attachment—59 percent among the consistently strong, 49 percent among the mixed, and just 40 percent among the consistently weak. Thus, consistently weak Democrats were more likely to consider themselves “born again” than consistently weak Republicans. In terms of feelings toward the Christian Right among Democrats, the overwhelming majority of the consistently strong and mixed categories placed themselves as being either far or very far from the Christian Right. However, only 42 percent of Democrats with consistently weak attachments did so. Among Republican activists, feelings toward the Christian Right among the consistently strong and consistently weak are almost the mirror image of each other. While a majority of the consistently strong felt close or very close to the Christian Right, only 15 percent of the consistently weak did so. Indeed, a majority of those Republicans with weak attachments felt far or very far from the Christian Right. Again, it is interesting to note that consistently weak Democratic activists felt closer to the Christian Right than consistently weak Republican activists. It should also be noted that among Republicans in the mixed category, only 37 percent felt close or very close to the Christian Right, and just over a quarter placed themselves far or very far from the Christian Right. While tensions between social and economic conservatives may have abated somewhat in state and local Republican Party organizations, these findings, nonetheless, continue to illustrate the potential that the Christian Right possesses as a source of internal divisions within the Republican Party.

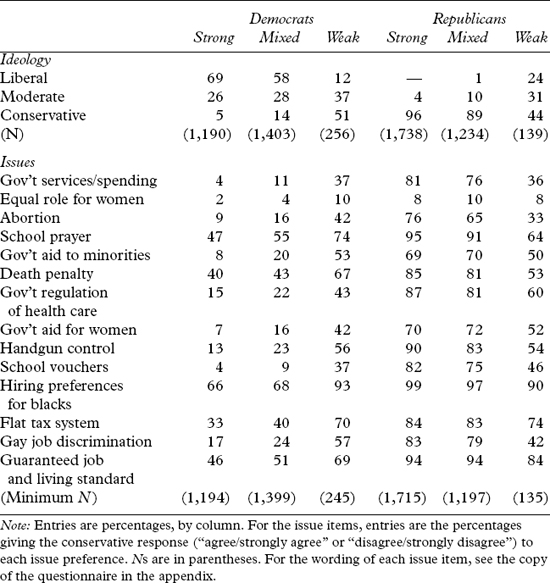

Scholars have emphasized a process of “ideological sorting” of the party coalitions in the South at the mass and elite levels (Black and Black 2002; McGlennon 1998b; Steed 1998; Knuckey 2001; Carmines and Stanley 1990). Given the effect of group orientations on political attitudes (see, for example, Singer 1981), a plausible hypothesis is that just as the ideological polarization of the two parties accelerated in the 1990s—a phenomenon evident outside the South as well (Abramowitz and Saunders 1998)—those activists with weaker party attachments are likely to hold ideological and issue preferences that are at odds with the mainstream views of their respective parties. Specifically, weaker party attachments should produce a moderating effect on each party (Bruce and Clark 1998). Table 6.4 presents the ideological orientations and preferences on specific issues for each set of activists by strength of party attachment.

Table 6.4 confirms that ideology is related to strength of party attachments, with 69 percent of Democratic activists considering themselves liberal and an overwhelming 96 percent of Republicans considering themselves conservatives. This underscores the process of ideological realignment in the South at the elite level culminating in the 1990s as discussed in detail in chapter 5. Indeed, only 5 percent of consistently strong Democrats considered themselves conservatives while no consistently strong Republicans considered themselves liberal. This general pattern also held for those in the mixed categories for each party, especially among Republicans, with 89 percent considering themselves conservative, while 58 percent of Democrats considered themselves liberal. It is only among Democrats with consistently weak attachments that one finds a majority considering themselves conservative. The ideological composition of the consistently weak is in marked contrast to the consistently strong and mixed categories, as only 12 percent considered themselves liberal. The ideological distance between Republicans with consistently weak attachments and the other categories is not quite as dramatic, as a plurality (44 percent) still consider themselves conservatives, while around a quarter consider themselves liberal. Overall, these findings suggest that the relationship between ideology and strength of party attachment, already strong in 1991, has become even stronger, and this is even more evident among Democrats than it is among the already ideologically homogenous Republicans.4

Table 6.4 Ideological and Issue Preferences of Local Party Activists by Strength of Party Attachment

Ideological differences between each category of party attachment were also evident in regard to the specific issue preferences presented in table 6.3. Among Democrats, the stronger the party attachment, the less conservative the preference on every issue. Large differences existed between the consistently strong and the consistently weak, with, on average, the consistently strong being thirty-one percentage points less conservative (more liberal) than the consistently weak. The distance on each issue between the consistently strong and the mixed categories was not as great, the consistently strong being, on average, just seven percentage points less conservative than the mixed category. Among Republicans, a similar pattern exists, with the consistently strong being more conservative than the mixed, who were more conservative than the consistently weak. The largest distances were between the consistently strong and the consistently weak, the former being, on average, twenty-six percentage points more conservative across the fourteen issues. The differences between the consistently strong and the mixed category were much more modest, the former being, on average, just four percentage points more conservative than the latter across the fourteen issues; and only on the abortion issues did the difference reach double digits.

Overall, ideology and issue preferences appear to provide the best explanation for variations in strength of party attachment. Those with consistently strong attachments in both parties are also the most ideologically polarized, and this seems to support the notion of the culmination of an ideological sorting at the elite level. While the consistently weak hold dissonant ideological and issue preferences from their respective party mainstreams, the scope for ideological and issue-based divisions seems less than it was a decade ago as a result of the very small number of activists in both parties who hold consistently weak attachments.

Strength of party attachment has long been regarded as an important predictor of a variety of modes of political behavior and participation among individuals (Lazarsfeld, Berelson, and Gaudet 1944; Campbell et al. 1960; Miller and Shanks 1996). Thus, party activists with weak party attachments should exhibit patterns of partisan behavior and activity that are less strong and widespread than those with strong party attachments. While activists should represent the core electoral base of the support in the party, differences in strength of party attachments do produce variation in the voting behavior of activists in both parties. Among Democrats, both the consistently strong and the mixed were almost unanimous in their support of both Bill Clinton in 1996 (99 percent and 94 percent, respectively) and Al Gore in 2000 (98 percent and 93 percent, respectively). However, among the consistently weak, a majority failed to support both Clinton in 1996 (48 percent) and Gore in 2000 (45 percent). Indeed, in 2000 a majority (51 percent) of Democratic activists with consistently weak attachments actually voted for George W. Bush. These defections, based on the findings presented here, appear to be attributable to the conservative ideology and issue preferences of the consistently weak. Fortunately, from the perspective of the Democratic Party, these defections are yielding fewer votes for Republican candidates given the decline in the size of activists holding consistently weak party attachments. Among Republican activists, there was also near unanimous support for Bob Dole in 1996 and for Bush in 2000 among both the consistently strong and the mixed categories. Some defections are evident among the consistently weak, 31 percent voting for Clinton in 1996 and 20 percent for Gore in 2000, although overall consistently weak Republicans tended to be more loyal to their party’s candidates than consistently weak Democrats were to their candidates.5

Strength of party attachment also appears to be related to patterns of political behavior beyond the simple act of voting, specifically with respect to levels of campaign activity. Among Democrats, 66 percent of those with consistently strong attachments reported being “very active” in local elections, and this dropped only slightly to 59 percent in both state and national elections. This pattern is also evident among Republicans, with virtually no variation across level of election—60 percent reporting that they were very active in local and state elections and 62 percent saying that they were very active in national elections. The degree of activity in elections among the mixed and consistently weak categories in both parties shows less commitment to campaign activity. While a majority in the mixed category for both Democrats and Republicans reported that they were very active in local elections (58 percent and 52 percent, respectively), only a minority reported being very active in state elections (42 percent and 41 percent, respectively), as was also the case in national elections (37 percent and 46 percent, respectively). As one might expect, among those with consistently weak attachments, less than half of the activists in both parties reported being very active at any level. Election activity among the consistently weak is most evident at the local level, with 46 percent of Democrats and 47 percent of Republicans reporting that they were very active. This drops off dramatically at the state level, with 26 percent of Democrats and 29 percent of Republicans being very active, and especially at the national level for Democrats, with only 18 percent reporting that they were very active, while 28 percent of Republicans did so.

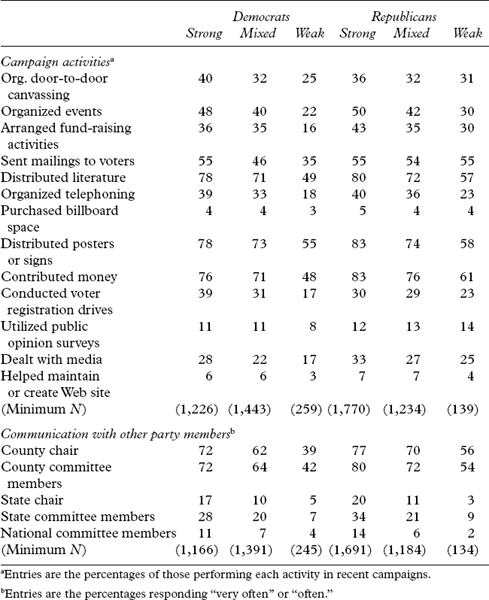

The effects of strength of party attachment are also evident when considering specific activities performed in recent election campaigns. The first part of table 6.5 shows the percentage of activists claiming to have performed each of thirteen campaign activities. Those with consistently strong attachments in both parties report the greatest levels of activities, which generally decline as party attachments weaken. Again though, the largest differences appear between the consistently strong and the consistently weak, with the average difference across the thirteen activities being sixteen percentage points among Democrats and ten percentage points among Republicans. Differences between the consistently strong and the mixed categories were fairly slight, on average about five percentage points among Democrats and four percentage points among Republicans.

Table 6.5 Activities Performed in Recent Campaigns by Local Party Activists by Strength of Party Attachment

These findings about voting behavior and campaign activity indicate the robust health of southern parties at the grassroots level. Specifically, the problems once faced by southern Democrats in mobilizing their base in national elections seem to have been resolved by the decline in those with consistently weak attachments. Again, while this pattern is still evident among Democrats with weak attachments, it is less consequential given the size of this group. At the same time, when one compares the consistently strong and mixed categories of both sets of party activists, there is little evidence now of large interparty differences. Among the consistently strong, for example, Republicans were only three percentage points more likely than Democrats to be very active in national elections.

Strength of party attachment should be related to a variety of measures that assess the extent to which party activists are integrated into the party organization at the grassroots level. Differences over party norms are related to some degree to strength of party attachment, although there are some important interparty differences. Mean scores on the purism index, as discussed in chapter 9, show that among both sets of party activists, the weaker the party attachment the higher the purism score. For example, among Democrats the mean scores for the strong, mixed, and weak categories were, respectively, 2.40, 2.55, and 2.87. These scores are on a four-point scale, with 4.0 being the most purist score. Among Republicans, a similar pattern was evident; the mean scores for the strong, mixed, and weak categories were, respectively, 2.63, 2.69, and 2.83. This is interesting, as chapter 9 suggests that purism is correlated with ideological extremism, and, as discussed earlier in this chapter, so too is strength of party attachment. Arguably, those activists with stronger attachments may have nonetheless adopted more pragmatic orientations as a consequence of the competitive elections in the South for all political offices.

The extent to which party activists communicated with other party officials also demonstrates a general level of integration into the party organization at the grassroots level. The second part of table 6.5 shows patterns of communication across each party attachment category. Those activists in both parties with consistently strong attachments were much more integrated into the communication network of their respective party organizations than those with mixed attachments and especially than those with consistently weak attachments. While the overall level of communication declines dramatically the farther one goes up the party hierarchy, this general pattern persists. One other point to note is that Republicans in each category of party attachment tended to report communicating “often” or “very often” more than Democrats. For example, even though consistently weak Republicans reported least communication with the party hierarchy at the county level, a majority still reported communicating very often or often with other county committee members (56 percent) and county chairs (54 percent). In contrast, Democrats with consistently weak attachments were much less likely to report communicating often or very often with county party members and chairs.

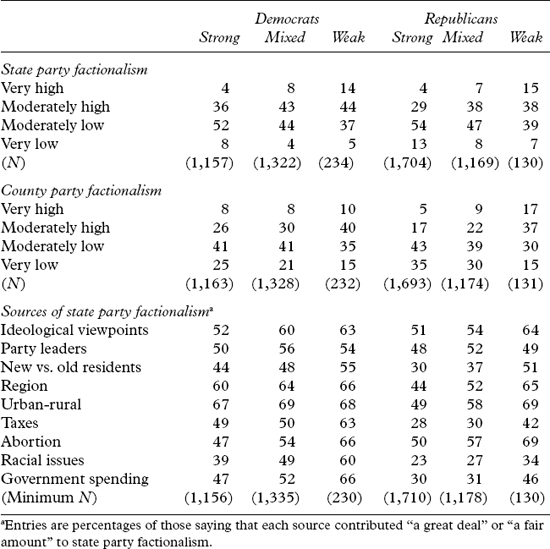

As discussed in chapter 7, internal party factionalism—or at least the perception of factionalism—remains evident in both parties. As strength of party attachment is related to ideological and issue preferences, and the latter contribute most toward perceived factionalism (see chapter 7), it is hypothesized that activists with weaker attachments will be more likely to perceive factionalism in the state and local party organizations. The differences discussed earlier about a religiosity cleavage may also produce perceptions of factionalism, especially among Republican activists.

The first part of table 6.6 shows that among Democrats, those with consistently weak attachments do tend to perceive greater internal party factionalism, with a majority saying that factionalism was either “very high” or “moderately high” in both the state and county party organizations (58 percent and 50 percent, respectively). This pattern also holds among Republicans with consistently weak attachments, with 53 percent and 54 percent, respectively, perceiving very high or moderately high levels of factionalism in the state and local party organizations. Among both sets of activists, perceptions of factionalism decline as party attachments strengthen. Indeed, among Democrats and Republicans in both the mixed and consistently strong categories, less than 10 percent perceived a very high level of factionalism.

The second part of table 6.6 shows the sources of the perceived factionalism in the state party organizations. The general pattern for activists in both parties was for the consistently weak to see each source as contributing “a great deal” or “a fair amount” to party factionalism more than the consistently strong or the mixed categories. Among Democrats, the largest difference in perception of the sources of factionalism does appear to be issue based. For example, the consistently weak were twenty-one percentage points more likely to perceive racial issues as contributing a great deal or a fair amount to state party factionalism than the consistently strong, and nineteen percentage points more likely to perceive differences on abortion and government spending to be the sources of factionalism. Among Republicans, the biggest differences on perceived sources of factionalism between the consistently strong and the consistently weak were differences between new and old residents (twenty-one percentage points), region (twenty-one percentage points), and urban-rural differences (twenty percentage points). However, Republicans in each category of party attachment seemed to be united in acknowledging that the abortion issue was an important source of factionalism. This was the only item, other than general ideological differences, cited by a majority in each category of party attachment as contributing either a great deal or a fair amount to state party factionalism. Overall, it is interesting to note that activists with weaker attachments—especially Republicans—tended to view as important each source contributing to state party factionalism. This suggests that it is not just the ideological dissonance of those with weak attachments that produces the perceptions of factionalism. Of course, this raises an important question of cause and effect. Do perceptions of greater levels of party factionalism contribute to weaker party attachments, or do weaker party attachments produce a greater perception of factionalism? Resolving this question is beyond the scope of this chapter, but it does suggest an interesting area for further research.

Table 6.6 Perceived Levels of Party Factionalism and Sources of Factionalism by Local Party Activists by Strength of Party Attachment

Party organizations in the South today consist of a cadre of activists who exhibit increasingly strong attachments to their respective parties. Compared to a decade ago the proportion of those with consistently weak attachments has fallen, and this has been especially evident on the Democratic side. It appears that the “weakest links” on the Democratic side are either no longer active or have realigned to fill the ranks of Republican Party activists. Among Republicans, those with consistently weak attachments, already small in number a decade ago, now account for less than 5 percent of all Republican Party activists. It should be noted, though, that a plurality of Democratic activists and a sizable minority of Republican activists continue to hold inconsistent attachments on at least one of four partisan variables.

In terms of explanations for different levels of party attachment, ideological and issue orientations seem to be most important. Among Democrats, the consistently strong were the most liberal; and among Republicans they were the most conservative. Differences based on religiosity and orientations toward the Christian Right also appear to be important determinants of party attachments. As a “values” or “secular-religiosity” cleavage appears to be coming more important in American politics more generally (White 2002), so it also appears that party elites in the South are polarizing around this cleavage. Those on the “wrong” side of this cleavage, that is, religiously committed Democrats and “secular” Republicans, evidently acknowledge this dissonance by exhibiting weak attachments.

The effect on the parties of activists with different levels of party attachment is not without consequence. Those with stronger party attachments exhibit much greater loyalty to party candidates and, more generally, are more involved and more committed to the party organization. As differences between the two categories of party attachment in which over 90 percent of activists in both parties are placed—the consistently strong and the mixed—were not very large, this suggests that southern party organizations now consist of intensely partisan and intensely committed individuals. This will certainly have ramifications on southern partisan and electoral politics in the years ahead. Candidates for political office will need to respond to the wishes of the base of their party, suggesting that elections in the South increasingly will present contests between a liberal Democrat and a conservative Republican. Such choices will, in turn, further widen the ideological and issue gap between the parties. Overall, the existence of strongly attached, committed, and ideologically distinct activists in both parties suggests that at the elite level there has been a culmination of partisan realignment. Southern party politics in the early twenty-first century can genuinely be characterized as possessing a rational and mature two-party system.

1. These percentages are based on those who held either strong national and strong state Democratic (Republican) Party identifications, or weak national and weak state Democratic Party identifications. Only 2 percent of both Democratic and Republican activists held split partisanship.

2. The party identification item differed slightly from that used by the American National Election Studies. Rather than the branching question format used by the NES, respondents were asked to locate themselves on a seven-point scale ranging from strongly Democratic to strongly Republican. The seven-point scale is identical to the NES party identification scale, however.

3. A detailed examination of state-by-state variations in strength of party attachments is beyond the scope of this analysis, but more information on state patterns is in Clark and Prysby (2003).

4. For example, in 1991, 53 percent of Democrats with strong attachments identified as liberals while 40 percent of Democrats in the mixed category did so (Steed and Bowman 1998, 195).

5. Interestingly, the defection rate in 2000 among Democratic activists is less than that found in 1988 when 67 percent of those with consistently weak attachments defected and voted for George H. W. Bush rather than Michael Dukakis. Also the Republican defection rate in 2000 was greater than that in 1988 when 13 percent voted for Dukakis rather than Bush. These data are taken from the analysis of the 1991 SGPA data by Steed and Bowman (1998).