The study of factionalism and its effects on southern politics has evolved with the development of two-party competition in the region. In an era when the South’s politics were distinguished by the absence of Republican organization, voters, and even candidates, factionalism provided a basis for explaining particular patterns of competition for political power and public office.

During the first half of the twentieth century, the eleven states of the Confederacy routinely cast their lot in national politics with the Democrats and maintained a nearly universal attachment to the Democratic Party. “No Southerner,” wrote John Crowe Ransom, “ever dreams of heaven, or pictures his Utopia on earth, without providing room for the Democratic Party” (Ransom 1930, 26). With all southerners assembled under the same party label, ambition and cleavage worked their ways in less formal vehicles of competition, party factions.

Often the “Solid South,” as it was described by historians and political scientists, was seen as a unified region without electoral division. The nearly unanimous Democratic label on public officials of the region overshadowed any consideration of contests for public office and policy outcomes. Challenging the notion of a monolithic Democratic South was one of the most significant contributions of V. O. Key’s Southern Politics (1949). Key recognized that this collection of eleven states may have been bound together by their common heritage of secession and Reconstruction, but their individual polities contained vast differences. Key’s identification of variations in factional competition in the southern states set the agenda for research on political competition in the region for decades. His classifications of states as having multifactional competition, bifactionalism, or a dominant faction within the dominant party led Key to suggest ongoing patterns in southern voting behavior. These patterns fell along regional or sociodemographic lines in some cases and around support for or opposition to personalities in others. He went on to hypothesize that the type of factionalism would affect the policy orientation of state government, with states exhibiting the characteristics closest to two-party competition also opting for policies geared to assisting the “have nots” of society (Key 1949, 307).

Key’s theories of factionalism were the basis for more research. Some focused on the public policy implications of his research, testing the hypothesis that party competition would lead to policies more attentive to the poor. Others focused more on the electoral mechanics of factionalism and how it would structure the choices for voters in one-party states. Black (1983) and Canon (1978) in separate studies tested the impact on factionalism of factors such as the primary system at use in each state (single versus runoff primary), the presence of an incumbent governor on the primary ballot, and the existence of a durable electoral faction. These studies were useful in testing the ways in which party nominations were contested even as the importance of the Democratic nomination was declining. They did not focus on the role that factionalism might play in the then-emerging two-party South. But as the South shed its one-party legacy and began to experience competition between Republicans and Democrats, factionalism took on a different importance.

Studies of competitive party systems have looked at the impact of factionalism on party organization and electoral success. Geer and Shere (1992) examine the effect of party primary contests on organizational strength and conclude that intraparty competition is important in aiding party responsiveness to voter wishes. Stone, Atkeson, and Rapoport (1992) find that candidate-centered factionalism may not be damaging to a party as even supporters of losing candidates are recruited to party activity, and Stone (1982) further finds that even delegates motivated by ideology put great stock in candidate electability.

Factionalism is often seen as having as much potential for growing support for a party organizationally and electorally as for being a serious source of party division. Studies of both U.S. political parties and parties in other nations show that factionalism can be a benefit for the party (Belloni and Beller 1976; McAllister 1991; Reiter 1981). While conventional wisdom often assumes that contests for party nominations are disruptive to electoral objectives, the contests often reflect a party that is expanding and broadening.

So most studies of factionalism have considered the phenomenon as an alternative to interparty competition in the one-party South or to test its implications for harm or good in two-party systems. Few efforts have attempted to look at the impact of factionalism specifically in the southern states as they have become two-party systems. One exception is an examination of Florida by Echols and Ranney (1976), which analyzed the impact of growing competition in Florida on the state’s Democratic factionalism.

The emergence of competition in the South over the past half century was accompanied by factionalism within both parties. For the newly enlarging Republican Party, growth carried with it tensions between loyal, longtime activists and newcomers or party switchers. Factional disputes often were identified by dominant personalities but reflected more persistent regional and ideological bases. The cleavages represented by U.S. Senator Jesse Helms and Governor James Holshouser in North Carolina, Governor Linwood Holton and party chairman Richard Obenshain in Virginia, and Senators Bill Brock and Howard Baker in Tennessee all neatly packaged regional and issue orientations in personally identified factions.

The formerly dominant Democratic Party found itself confronting a difficult transition. The winners of intraparty tests were rewarded with public office in the Solid South. The two-party South’s Democratic candidates won a nomination that did not guarantee victory and, in fact, had often served to drive the losing faction toward competitive and eagerly awaiting Republicans. John Tower became the first southern Republican elected to statewide office in 1961 because liberal Democrats believed that they were better off supporting a one-term Republican than backing the conservative Democrat who won the party’s nomination. Over the course of three decades, Republican successes in most southern states often resulted from ideological cleavages in Democratic primaries, as the party gradually moved toward the profile of northern Democrats.

The decade between 1991 and 2001 brought the culmination of party realignment to the South. Despite the national success of southern Democrats Bill Clinton and Al Gore in both 1992 and 1996, and Gore’s popular vote victory in 2000, regional Democrats completed the twentieth century with their worst share of elected offices since the establishment of the post-Reconstruction Solid South.

President Clinton’s first two years in office proved especially unpopular among southern white voters, who opposed his policy of toleration for homosexuals in the military and saw his health care proposals as an expansion of “Big Government.” In combination with congressional scandals and redistricting, which matched a number of new “majority-minority” congressional districts with an even larger number of newly configured Republican-friendly suburban districts, Republicans won a majority of southern U.S. House seats in 1994. They also regained a majority of the twenty-two Senate seats from the South, and in both cases, their southern margins provided the majorities that gave them unified control of Congress for the first time in forty years.

Despite their losses, Democrats demonstrated a continuing ability to compete. After the 1994 debacle, they managed to elect new Democratic senators and/or governors in all of the states except Tennessee and Texas (and have since won the Tennessee governorship).

Organizationally, both parties generally recognized the need to strengthen their recruitment of candidates and activists, improve their technology, and raise money. There was no doubt that the parties had to adapt to changed circumstances. Factionalism was bound to be part of the new party structure in the South.

This chapter examines the evolving nature of factionalism in the southern parties as seen by the precinct activists of those parties. Utilizing the Southern Grassroots Party Activist surveys conducted in 2001, we examine their perceptions of factional divisions and compare these results to the study conducted a decade earlier. We also consider whether the perception of factional division is related to the characteristics of the party membership and whether it appears to influence their views of the party’s organizational and campaign effectiveness. The first SGPA Project provided the opportunity to measure the level of factionalism among precinct-level party organization members in the eleven states of the Confederacy (McGlennon 1998a). It also allowed examination of the relationship between perceptions of party factionalism and party organizational strength.

The current project allows for a further examination of the factionalism confronting the parties. As the parties have continued to evolve, we can observe whether they have become more internally consistent or diverse. It should be evident whether party factionalism is currently seen as more or less of a party problem and whether it bears any relationship to perceptions of party effectiveness.

Factional divisions within the parties were inevitable outgrowths of the changes in party competitiveness and party composition. As discussed elsewhere, realignment of the southern electorate increasingly meant that conservative activists would find their homes in the Republican Party and moderates and liberals would be found in the Democratic Party. The preponderance of black voters in the Democratic Party is reflected by an even more racially polarized set of party activists than in 1991.

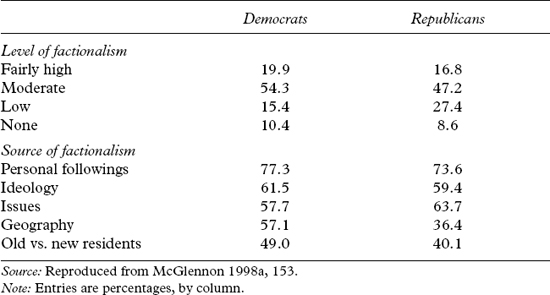

Table 7.1 Level and Sources of Perceived Factionalism among Activists, by Party, 1991

In many ways, the parties became more internally consistent over the decade between the two SGPA studies, and the activists’ perceptions of party cleavage reflect this in an apparent lessening of tension. Table 7.1 shows how activists viewed the presence of party factionalism in 1991. Almost two-thirds of Republicans and nearly three-quarters of Democrats viewed factionalism as being “fairly high” or “moderately high.”

In this earlier survey, activists were also asked to indicate which of five sources of factionalism existed within the party. Democrats saw division almost everywhere, with a majority saying four of the five sources were present in their party. The fifth was identified by 49 percent. Personal followings were most commonly mentioned, with 77 percent of Democrats saying they had seen evidence of such schisms. Ideological tension ranked second.

Republicans found fewer causes of factionalism present, but again personal followings ranked first, with slightly less than three-quarters noting its presence. Issues were next, followed by ideology, while fewer than half found tensions caused by geographical division or rivalries between new and old residents of their states.

By 2001, factionalism seemed to be a less significant problem in both parties, though differences in question wording make direct comparison problematic. Still, when asked to describe the level of factionalism in their state and county party organizations, solid majorities of both Democrats and Republicans described it as “very low” or “moderately low” at the state and county levels.

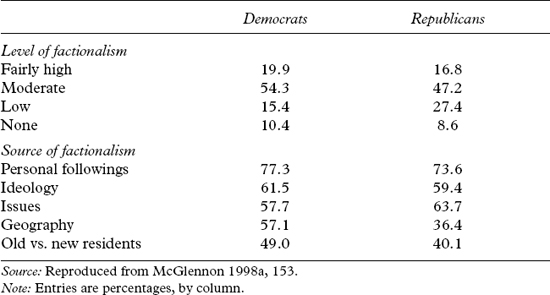

Though the levels of factionalism might be low, the party activists still found it to be present and based on numerous sources, as shown in table 7.2. Activists in 2001 were presented with nine potential sources of factionalism, and majorities of Democrats claimed high levels of factionalism in seven of the cases (with 47 percent adding the last two). In contrast, Republican activists perceived high factionalism in only four of the nine causes.

Table 7.2 Level and Sources of Perceived Factionalism among Activists, by Party, 2001

Democrats most commonly cited urban/rural and regional division, with ideology next. Party leaders were fourth on the list of sources of factional division. Republican activists were most likely to name ideology and abortion as causes of division, with urban/rural conflict and support for contending party leaders ranking close behind.

The overall decline in perception of factionalism is consistent with the ongoing realignment of the parties. Even so, the continuing identification of ideology by activists in both parties, as well as issue differences on abortion for Republicans, suggests the continuation of friction under a unified surface. Not surprisingly, table 7.3 shows that the identification of factionalism over ideology tracks with an activist’s own ideological positioning. The more conservative the Democratic activist, the more likely he or she is to see factionalism over ideology. Among Republicans, who primarily distinguish themselves in shades of conservatism, the less conservative the activists, the more likely they are to see factionalism. In these cases, it appears that the perception of factionalism may be enhanced by holding a less common view within the party. The increasing polarization of the parties means that there are fewer conservative Democrats or moderate Republicans to feel engaged in a factional dispute within the organization.

Table 7.3 Perception of Factionalism among Party Activists by Ideology and Abortion Attitude

Similarly, the identification of abortion policy as a source of factionalism appears closely related to a respondent’s position on legalized abortion. The closer to the dominant party position an activist is, the less likely he or she is to see this as a highly factional issue in the party.

How does the perception of factionalism match actual disagreements or varying perceptions among party members? And how do changes in party composition serve to explain declining levels of factionalism?

It must first be recognized that the parties have become less ideologically diverse than they were ten years earlier. On the five-point scale of party identification, a majority of Republicans in 2001 identified themselves as “very conservative,” up 13 percent from the earlier study. Liberals and moderates dropped from 15 percent to 9 percent of Republican Party members. Democrats experienced a similar if more modest trend toward ideological unity. Liberals constituted 57 percent of Democratic activists, an increase of 20 percent over 1991. Moderates and conservatives dropped to 43 percent among Democrats. In both cases, the level of factional diversity in the party has declined, but the perception of ideology as a divisive force remains.

Abortion was seen by a majority of both parties as an important explanation for factionalism, despite the fact that both parties saw increasing consensus among their activists. Republican support for legal abortion fell from more than 40 percent to just 30 percent. Democratic support jumped from just below 75 percent to 85 percent. Those on the minority side in each party were even more likely to see abortion as a cause of factionalism, suggesting that they were increasingly aware of their divergence from their party’s majority opinion on the issue. The sensitivity may come as party leaders and candidates increasingly reflect a consensus position that these activists do not share. It also suggests the possibility that these activists may be the remnants of a larger group who have already exited each party over issue differences.

Those among the activists who have switched parties give us some indication of the impact that issue factionalism may have. Among the activists who reported that they had been members of another party previously (about 5 percent of Democrats and more than 10 percent of Republicans), the overwhelming reason reported for the party change was that the new party of the activists had a better stand on issues. Two-thirds of those who switched to the Democrats and 84 percent of Republican converts selected issue stands as the most important reason for the change. For both sets of partisans, their positions on the issue of abortion were consistent with their new party’s dominant stance and at variance with their former party. Issue factionalism both explains the movement of party switchers and suggests a continuing impact on those who increasingly feel themselves at odds with their own party.

The emergence of regional and urban/rural factionalism reflects a different dynamic at work in the southern party systems. Regionalism is not new in southern politics, of course. Key devoted considerable attention to the concept of “friends and neighbors” voting and to identifying ongoing geographic or regional bases for candidates and even parties. But the return of regional factionalism does suggest more stable patterns of intraparty competition.

While ideological and issue differences were disappearing among local party activists, they seemed to be increasingly cognizant of differences among party members based on where they lived. The distinction did not seem to be between newcomers and longtime residents or natives, but rather among sections of states and metropolitan versus rural areas. With the South as a whole still more rural than the rest of the country, but large sections of it rapidly urbanizing, a clash of values is predictable. It also presages a more permanent source of controversy as urban areas require higher levels of service, exhibit more diversity and tolerance, and are oriented toward economic and social expansion.

Examples of urban/rural divisions in southern state politics abound, whether it is the split between congested South Florida and the Panhandle, the Atlanta metropolitan gargantuan and the peanut farms of Plains, or Northern Virginia’s constant battle over state resources with Southside. Regional rivalries have been well documented in Tennessee’s Grand Divisions, the Delta versus the Hills, and the Low Country of South Carolina against the Upcountry. But as party competition has come to the South, other factors have often weakened regional tendencies from early eras.

With the emergence of factionalism based on region and urbanism in both parties, it suggests a more fundamental change in the organization of politics. Different perspectives on the need for and extent of state services are likely to be seen in both parties and to result in conflicts at all levels: elections, state and local governments, and party organizations. As metropolitan areas grow, it becomes more difficult for either party to hold together a coalition that includes varied regional and locational interests.

These results suggest that the overall decline in factionalism experienced by the parties over the decade is largely the result of increasingly unified opinions among party activists. It also suggests that as party competition has become more regularized, party positions and bases of support become more stable. If this is true, it should be evident in differences among state party systems.

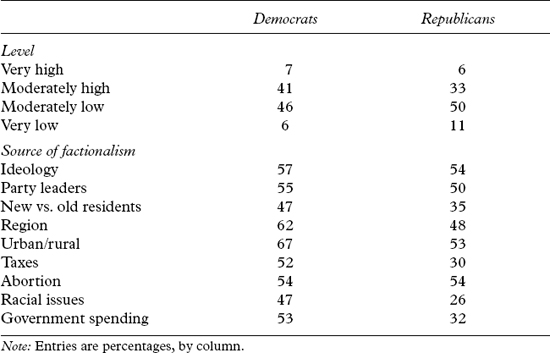

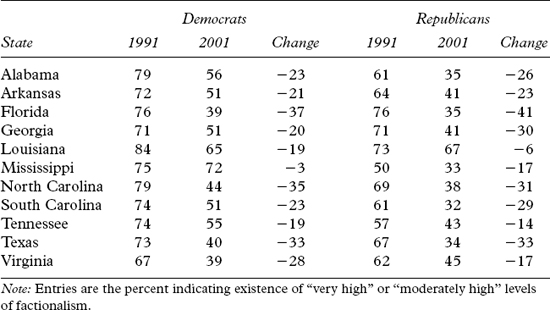

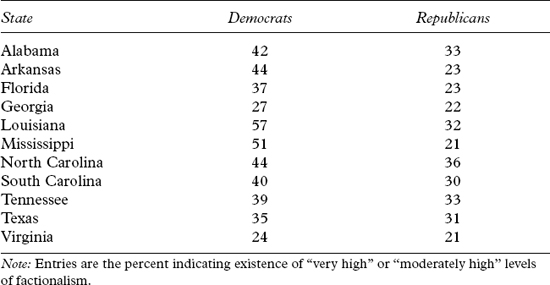

In the 1991 survey of activists, three results stood out in the analysis of activists in the individual state parties. First, the perception of factionalism was high across the board, with a majority of the party activists in both parties in every state so indicating. While Mississippi Republicans barely hit the majority, in most cases well over 60 percent of activists of other state parties cited high factionalism as present in their organization. Second, Democrats perceived higher levels than Republicans in nine of eleven states, tying with Republican activists in Florida and Georgia. Third, the range among each party by state was relatively small, clustering close to the average score in all but a handful of cases.

The 2001 results show greater variance, as shown in table 7.4. In fourteen of the state parties (ten Republican and four Democratic), perceptions of high factionalism had declined to minority levels. In two states, reported factionalism by Republicans actually exceeded the Democrats’ reports. Finally, the range of percentages was much higher, especially for the Democrats.

Consistent with the reports that regional and urban/rural divisions are among the leading sources of factionalism, party activists report much less disagreement within their county organizations (table 7.5). Reports of divisions between urban and rural activists and among activists from different regions are in some contrast to the harmony reported at the local level. With some important sources of factionalism not relevant (local committees will be comprised of activists from one region and most often from counties that are either urban, rural, or suburban), factionalism overall should be much lower.

Of course, factionalism’s impact will be felt differently in the varied states of the region. The 1991 SGPA survey found that while majorities in both parties in all states found factionalism to be high, the level of recognition ranged from a low of 50 percent to a high of 84 percent. Among Republicans, there was a spread of 26 percent between the high and low states, while the Democratic range was only 17 percent, including the state with the highest level of reported factionalism. While much more detailed discussion of factionalism in individual states can be found in Clark and Prysby (2003), some state variations are worth commenting on here.

Table 7.4 Perception of Factionalism in State Parties, 1991 and 2001

Table 7.5 Perceptions of Factionalism in County Party Organizations, 2001

The significantly lower levels of factionalism reported in 2001 were largely consistent across both parties and most states. While activists in a couple of state parties still found factionalism to be high, it was reported by fewer than half among Republicans in ten states and Democrats in four. Each party experienced a 24 percent overall decline in reported high factionalism. South Carolina, Mississippi, Texas, and Florida had the lowest levels among Republican activists, while Florida, Virginia, Texas, and North Carolina had the Democratic Party organizations with the lowest rates. Louisiana stood out in both parties as highly factional, with only Mississippi Democrats reporting a higher level.

The explanations for low and high levels of factionalism are not immediately evident from this data, but their experiences in party development are suggestive. For the Republicans, the least factional states are ones in which they have experienced enormous success and have established their power in state and national elections. The Democratic states with low factionalism are generally those that faced strong Republican opposition early and have had the most time to adapt to a changing political environment. Their members may represent a more coherent body of activists who recognize that they no longer have the luxury of internal division.

The three high factionalism state parties represent a different set of circumstances. Both Louisiana parties operate in an electoral system that works against party unity and discipline, at least in its early stage. The “free-for-all” primary makes each candidate, regardless of party, put together a personal coalition of support with the goal of winning a spot in a runoff against another candidate who may even be of the same party. That electoral mechanism is tailormade to encourage factionalism. The Mississippi Democrats presumably face the difficulty of holding together a party consisting of traditional white Democrats, who continue to hold local and state legislative positions, and African Americans, who are the electoral backbone of the Mississippi Democrats. With African Americans comprising 47 percent of Mississippi’s Democratic activists, the state presented a unique racial profile. No other state party came close to the nearly equal division of Mississippi, with South Carolina’s African Americans constituting less than a third of the total activists.

Another source for trying to understand the interstate variations is the identification of specific sources of factionalism by the party activists. The results lend support for the contention that Louisiana’s high rate of reported factionalism is due to candidate-centered politics, as 71 percent of Democrats and 61 percent of Republicans from the Pelican State cited factionalism based on party leaders. Georgia Republicans, who have had a series of close statewide nomination contests in recent years, also reported a high level of personal factionalism.

Georgia and North Carolina Democrats and Tennessee Republicans identified the split between new and old residents as a source of unusually high factionalism, consistent with the relatively high growth rates these states have experienced. However, this finding did not appear in other fast-growing states. Regional divisions were noted most frequently by both Democrats and Republicans in Virginia, and by Tennessee Republicans. Members of both parties in Georgia, Louisiana, and Virginia pointed to urban/rural division, as did North Carolina Democrats and Tennessee Republicans.

Though Republicans across the South found little to disagree on over tax policy, in Tennessee it was a source of deep division. Compared to only 30 percent of Republicans overall naming tax policy as a source of factionalism, 68 percent of Tennessee’s Republicans found tax policy a source of division. With the Volunteer State in the midst of a bitter fight over adoption of an income tax proposed by Republican Governor Don Sundquist, the issue was a top source of Democratic friction as well. Louisiana Democrats also cited this issue as a source of factionalism.

Although factionalism may have declined, we have seen that it remains a concern among significant numbers of southern party activists. The sources may be different than a decade earlier, but the implications of a divided party can be serious. In order to investigate the impact of factionalism, we focus on those who reported their perception of party factionalism to be very high. These activists, as we have seen, are likely to be disproportionally in the minority in their own party on those dimensions that lead to factionalism. If there are consequences to their sense of division, they are likely to be among this group.

In order to examine the implications, we first consider how strongly these activists identify with their party and its candidates at the state and national levels. We then turn to the level of activity that these precinct party members report and finally look to their views on the appropriate roles for party members to play when confronted with sources of division.

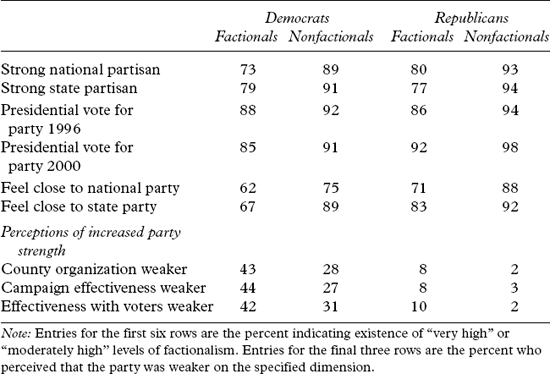

Do party members who report high levels of factionalism in their state organizations retain strong attachments to their parties? Not surprisingly, precinct organization members view themselves as strong partisans. If they lose attachment to their party, why would they continue to hold even lower level positions in the organization? That question must frequently come to the minds of activists who see themselves in a divided organization, as they do report lower levels of strong affiliation.

As it turns out, large majorities of precinct activists do see themselves as “strong” partisans, but among both parties, the activists who find high factionalism (hereafter referred to as “factionals”) are much less likely to profess this strong attachment (table 7.6). Concern over factionalism is also evident in levels of support for the presidential candidacies of both parties in both 1996 and 2000. While large majorities of activists supported their party’s nominee each time, factionals were consistently (though only modestly) less supportive. In addition, when describing their attachment to their state and national parties, factionals were much less likely to identify themselves as close to either their state or local party.

This loosening of attachment to the party by some factionals manifests itself in the perception of the party’s strength and effectiveness as well. Republicans overwhelmingly view their party organizations as having gotten stronger over the past decade, and Democrats are more restrained in their evaluation, but factionals consistently have a more pessimistic view of the party change in organizational and campaign effectiveness and in effectiveness with voters.

So factionals have weaker attachment to their party and its candidates and are less likely to believe that it has strengthened itself in recent years. Does this affect the way in which these activists function within the party? To answer this question, we examined the reported activity levels of factionals compared to other party activists and how they resolve the tension between electability and ideological purity.

Table 7.6 Perception of Factionalism and Attachment to Party

Democratic factionals show a predictable pattern of activity: they are most active in local elections and least active in national campaigns. While those Democrats who reported little factionalism maintained consistent levels of activity in local, state, and national campaigns, factionals put in their strongest effort for the local candidates who were more likely to match their own ideological and issue preferences.

Republican factionals worked at the same level as other Republicans in local and national campaigns but were less active at the state level. Since factionalism generally was reported to be at higher levels in state parties than local ones, it is not surprising that activists were more likely to sit out a state election. For Republican factionals who took less conservative positions on issues, moderate southern Democrats running for state office might provide less motivation for involvement than more liberal national Democrats. A fuller discussion of questions relating to the pragmatism and purism of party activists can be found in chapter 9.

The second Southern Grassroots Party Activists survey paints a picture of political parties in a newly competitive system with declining and changing causes of factionalism. As ideological and issue variations within each party have narrowed, both the Democrats and Republicans report lower levels of factional division within their respective organizations. Ideological polarization continues, and, as it does, the parties may continue to experience factionalism, but it is declining.

As the traditional source of factionalism is easing, however, a new and important source of potential division is being recognized: conflict based on regional and urban/rural distinctiveness. This source of factionalism reflects both a more stable and predictable cause of cleavage within the parties and a potentially significant wedge within party organizations.

Metropolitan growth is transforming the South and challenging dominant political views in ways that carry the possibility of pitting party members against each other. Rural communities with strong attachments to traditional values will more frequently confront policy initiatives coming from urbanizing areas, both in state parties and state government. The challenges confronted by politicians of both parties in keeping together disparate coalitions in the face of issues and controversies such as the design of state flags, abortion, homosexual rights, religion, and government services are seen increasingly.

Georgia’s Democratic Governor Roy Barnes lost his reelection bid unexpectedly in 2002 despite increased support in metropolitan areas because of the wholesale abandonment of his candidacy by rural voters, partly over the state flag issue. Republican Sonny Perdue had just taken over the governorship when he had to figure out how to balance the expectations of his rural supporters that he would restore the Massive Resistance era flag and the demands of corporate Republicans that he drop any effort that would paint Georgia as intolerant and backward looking.

Democrats must simultaneously maximize support among African Americans and avoid alienating moderate suburbanites, while limiting their losses in small towns and farmlands. Republicans have to motivate Christian conservatives with strong support for governmental restriction of social liberalism while appealing to libertarian instincts of gun owners and not driving away the “soccer moms” who represent a key swing constituency in many southern states.

Just as significantly, emerging debates on government taxing and spending policies are already creating deep divisions in both parties, but especially the emerging majority Republican Party. Our survey has revealed the deep division in Tennessee, where a Republican governor became a pariah by advocating a restructured tax system designed to raise money for enhanced state services. Alabama’s Governor Bob Riley was handed a landslide defeat when he tried to convince voters to adopt a new tax system designed to raise $1.2 billion in additional state revenue. Virginia’s Republican State Senate and House of Delegates engage in annual skirmishes over conflicting views of taxing and spending.

Increasingly, as urban areas press for more state funds to pay for traffic improvements, better quality schools, economic development, and enhanced environmental protection, regional schisms become more and more pronounced. The ability of the parties to respond to this new source of factionalism will help to determine the nature of party competition in the South in the decade to come.

At this point, the impact of factionalism in this new system is unclear. The evidence from this study suggests that factionalism will inherently appear in parties that are dynamic and growing and in systems where party competition is vital. It does not appear to create major problems for parties in maintaining the active support of even those who represent a minority viewpoint within the party, but it does suggest that those who find themselves increasingly isolated within the organization may exit its ranks.