The central task of a political party is to elect its slate of candidates to positions of power within the government. To that end, party organizations perform a variety of different activities, from registering voters and raising money to recruiting candidates and waging get-out-the-vote drives. Previous studies demonstrate that these activities have many important consequences, not the least of which is an influence on election outcomes (Cotter et al. 1984; Frendreis, Gibson, and Vertz 1990). For these reasons, a close examination of campaign efforts by parties and the factors that motivate them are important to our overall assessment of party organizations in American politics.

The present analysis considers the role of grassroots party activists in campaigns and elections in southern states. In what ways do these party operatives participate in campaigns? Are some of the tasks they perform more common than others? What differences do we see between the two parties in terms of specific tasks performed as well as in overall effort? Have there been any changes in the extent of activity over the past decade? Given the movement toward two-party competition in most southern states, do we see any increase in activities by the parties?

In addition to questions of what party operatives do in campaigns, the analysis is also concerned with those factors responsible for shaping these activities. What characteristics associated with activists themselves are responsible for their degree of involvement? For example, how important is their position within the party (county chair or county committee member) to their overall participation? How do such factors compare with the perceptions of party strength and factionalism in affecting the extent of their campaign-related work?

Results of the analysis demonstrate that campaign and election activities by those at the grassroots have increased over the past decade, although the increase has been much greater among Democrats. When we hold constant a large number of variables, we find that Democratic activists are engaged in a larger number of campaign activities than their Republican counterparts. Whereas Democrats lagged behind in the early 1990s, by 2001 they appear to have caught up to the gains made by Republicans during the 1980s and early 1990s. These findings suggest the groundwork continues to be laid for a more competitive two-party system throughout the southern region.

The role of political party organizations in U.S. elections has changed dramatically over the past century. The growth of primaries, the use of the secret ballot, and the diminished influence of political patronage have altered many of the traditional sources of party strength (e.g., Epstein 1986; Mayhew 1986; Reichley 1992). Parties are no longer the sole agents of candidate recruitment, and many of their grassroots functions have been supplanted by campaign professionals such as pollsters and media consultants versed in “new-style” electioneering practices (Agranoff 1976; Wattenberg 1994). Elected officials often create their own “permanent campaigns” (Blumenthal 1982) for the purposes of communicating directly with constituents from election to election. Overall, the party-centered era of politics has given way to a decidedly more candidate-centered environment (e.g., Menefee-Libey 2000; Salmore and Salmore 1989).

But such changes have not led to the demise of party organizations. As Paul Allen Beck (1997, 247) notes, “many have come to the conclusion that the traditional grassroots party organization has become technologically obsolete—that it has been superseded by newer, more efficient, and more timely avenues and techniques of campaigning . . . [b]ut this conclusion overlooks the great adaptability of the party organizations.” Over time, the needs of candidates created a way for parties to assume a larger role in political campaigns. Beginning in the 1970s, a resurgence occurred in national and state parties, in part as organizations began to adopt a more service-oriented approach. As Bibby (1999b, 195) notes, “[m]ost state party organizations today bear scant resemblance to either the traditional party organization of early in this century or the weak organizations that were so characteristic of the 1950s and early 1960s.” Parties on many different levels now provide a variety of services to candidates to aid in their election efforts including polling, fund-raising assistance, and media services (Aldrich 1995; Cotter et al. 1984; Reichley 1992). Thus, parties have embraced changes in campaign practices by carving out new sources of strength for their organizations.

Studies from a variety of perspectives demonstrate the important role played by parties in the election process. Studies of the past focused primarily on the grassroots and labor-intensive efforts of parties to get out the vote and found mixed results for these activities (e.g., Cutright and Rossi 1958; Katz and Eldersveld 1961; Kramer 1970). However, more recent work shows that party efforts can and do have important electoral consequences, (e.g., Cotter et al. 1984; Frendreis et al. 1990; Wielhouwer and Lockerbie 1994), particularly through their provision of services to candidates in congressional (Herrnson 1988) and state legislative elections (Hogan 2003). The present analysis continues this inquiry by examining party efforts from the perspective of those at the grassroots who are most often responsible for carrying out these activities.

Building on earlier work that examined such questions in the early 1990s, the goal is to understand the vitality of these organizations and perhaps gain a perspective on their role in elections. Such questions are particularly instructive in southern states where two-party competition continues to rise. Whereas previous studies found parties in southern states to be less active than in other parts of the county (Cotter et al. 1984; Mayhew 1986), results of an analysis in early 1991 found southern parties active in a number of campaign-related areas (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998). This study found that “most organizations are active in campaigns, and the emergent Republican activists tend to be more involved than their Democratic counterparts” (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998, 133). A decade later, do we find local parties playing a similarly active role? Have their activity levels increased, decreased, or stayed about the same? Are the factors that were once responsible for variations in party activity still having an important effect?

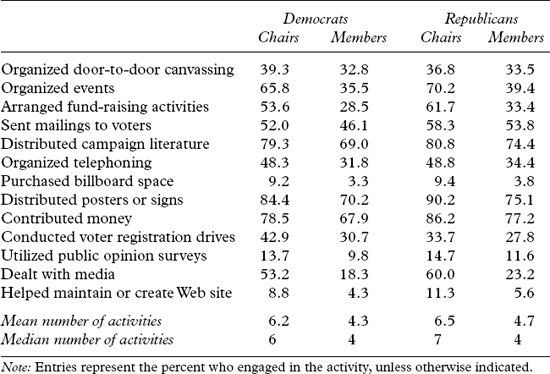

What role do grassroots party activists play in campaigns and elections? Table 11.1 provides the percentages of county chairs and county committee members by political party who engage in thirteen different types of activities. Summary measures for overall activity levels (means and medians) are also reported for each group.

Some campaign activities are clearly more common than others. For example, nearly 70 percent or more of county chairs and committee members alike report distributing campaign literature, distributing posters or lawn signs, and contributing money to campaigns. However, very few activists report purchasing billboard space, utilizing public opinion surveys, or helping to maintain a campaign Web site. Thus, the most widely used techniques are also some of the most traditional forms of electioneering. “New style” or “modern” techniques (opinion polls and Web sites especially) are used much less frequently. Such a finding is surprising given the attention in the literature to the increasing use of modern electioneering practices.

Table 11.1 Campaign and Election Activities, 2001

One clear pattern that emerges is the higher levels of involvement reported by county chairs compared to county committee members within each activity category. Among Democrats, chairs report an average of 6.2 forms of participation while members report only 4.3. For Republicans, a very similar picture emerges, where the average number of activities for chairs is 6.5, while for members the average is only 4.7. In addition to these overall trends, it is important to note that on some dimensions the difference between chairs and members is quite substantial. For example, nearly twice as many chairs than members report organizing campaign events and arranging fund-raising. Chairs are nearly three times more likely than members to report having “dealt with campaign media.” Such higher rates of involvement reported by chairs are not surprising given that many of the differences are among activities that can be considered managerial in nature. Analyses of the 1991 data reported similar findings and noted that such differences represent a division of labor within the organization that may be interpreted as evidence of a relatively sophisticated organization (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998).

Another pattern emerging from table 11.1 involves the different levels of activity reported by Democrats and Republicans. The 1991 survey found that Republicans were more involved in a larger number of areas. Results from 2001 suggest that this pattern has not changed dramatically over the last decade. Among chairs, Republicans are more active than Democrats in eleven of the thirteen areas examined (among members they are more active in twelve areas). It is only for voter registration drives where Democratic chairs and members report higher levels of activity than their Republican counterparts. For the mean scores, Republicans chairs report an average of 6.5 activities, while Democratic chairs report 6.2. Among members, the mean is 4.7 for Republicans and 4.3 for Democrats. Overall, the Republican activists appear to utilize a wider assortment of campaign and election techniques.

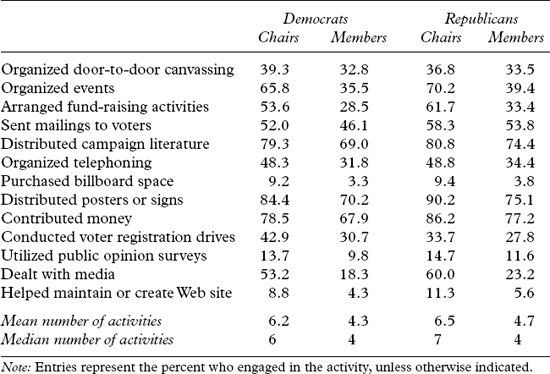

Table 11.2 Change in Campaign and Election Activities, 1991 to 2001

A key question is whether or not campaign activities performed by party activists have changed over time. Given the continued rise of two-party competition in most southern states, we would expect to see increased rates of involvement by activists in both parties. It would seem that Republican activists would be working to continue establishing their party’s presence while Democratic activists would be working to counteract these changes. To determine if such trends are present, table 11.2 shows the percentage point change in reported activist involvement (positive or negative) in the twelve areas where comparisons are possible.1

The results show convincingly that party activity increased over the last decade. While there were reductions in the use of some activities, for the vast majority of items, reported use grew over the time period. For some activities these changes were minor (e.g., organizing campaign events and public opinion surveys), but for others the increases were substantial (e.g., sending mailings and distributing posters or lawn signs). Comparing the average number of activities in each time period at the bottom of the table demonstrates changes in overall activity levels. While average increases are reported for all four categories of respondents, it is important to note that the largest increases occurred among Democrats (for both chairs and members). Such findings suggest that during the 1990s, the period of Republican growth in campaign activities began to plateau while Democratic activities grew, perhaps in response to Republican electoral gains.

Now that we have some sense of the types of campaign activities that are used by those at the grassroots, we now turn to factors that explain variations in overall party campaign activities. It will be interesting to see if the different levels of activity seen between chairs and members and between the two parties persist in multivariate analyses where controls are included for a variety of variables.

Previous analyses have identified a number of variables responsible for variations in levels of campaign activity at the grassroots (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998). Many of these same factors are examined here along with several additional variables. Of particular concern is whether factors responsible for differences in activity in the early 1990s continue to have a similar effect. Ordinary least squares analysis is used to determine the relative impact of independent variables on overall levels of campaign activity. Such a statistical analysis enables us to gauge the independent impact of each variable while holding constant all the other effects. The dependent variable is a summary measure for the number of activities reported by each respondent. The activity scores range from a low of 0 to a high of 12.

Perceptions of the local party organization are expected to play a large role in campaign involvement. Where local parties are strong, we expect to see those at the grassroots engaged in a larger number of activities. To gauge the level of party health, an index was created based upon responses to five questions about the local party’s strength. Respondents were asked to use a five-point scale to indicate whether the local organization was stronger or weaker than a decade ago on several dimensions: overall strength, campaign effectiveness, ability to raise funding, the role in recruiting candidates for office, and efforts to develop the organizational skills of workers. Responses were combined into an index where values ranged from 0 to 20, with higher values indicating greater organizational strength. It is expected that where local parties are perceived to be stronger, more effort will be directed toward campaign and election activity.

Another feature of local parties likely to influence activity is the degree of factionalism within the party. From one perspective, one might expect that greater conflict within a party would reduce the organization’s ability to engage heavily in campaign activities. It would seem that fractured parties would have difficulty deciding where to direct organizational effort and activists would simply participate at a lower rate. However, previous studies show that greater factionalism is, in fact, positively related to party activity. Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer (1998, 131) explain this finding from their examination of 1991 survey responses by saying that “rather than driving activists out through disenchantment, [factionalism] acts as a catalyst for increased activism, perhaps in a competition for control of that party.” It will be interesting to see if this effect is present in 2001 or if the influence of factionalism has subsided over time. This variable is measured based upon responses to a question concerning perceptions of factionalism within the party on a four-point scale. The variable ranges from 0 (low factionalism) to 3 (very high factionalism).

A second set of factors expected to influence campaign activity involves the attitudes and beliefs of party members. A major component of belief structure relevant for understanding variation in campaign activity is the degree of pragmatism or purism expressed by a party member. Previous studies define purists as those concerned more with issues and ideological correctness while pragmatists are those interested primarily in political victory (see chapter 9 for a more detailed discussion of this concept). Research finds such attitudes are important in explaining a wide variety of other attitudes and behaviors among party activists (e.g., Abramowitz and Stone 1984; Prysby 1998b; Wilson 1962) as well as those specific to campaign activity (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998). Given these previous findings, we should see greater activity among pragmatists than among those who espouse a purist orientation. Here, the purism versus pragmatism continuum is operationalized as an index of party purism based upon responses to questions about the role of party organizations in elections. The index ranges from 1 to 4 with increasing values of the index representing greater support for the party purism position. If the results match our expectations, the coefficient in the multivariate analysis should be negative.2

Closely linked to the party purism dimension is political ideology. Do activists describe themselves as liberal, conservative, or moderate in their orientations? It would seem that those who are more extreme in their ideology would be motivated to engage in a larger number of campaign activities. Indeed, previous studies identify such a linkage—activists whose orientation is closer to that of their national party exhibit greater involvement (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998). This means that among Democrats, the liberals should be more active than moderates or conservatives, while among Republicans, conservatives should be more active than moderates or liberals. A variable measuring activist ideological placement relative to the dominant orientation of his or her party is created based upon self-placement on a seven-point ideological scale. Higher values on this measure indicate greater agreement with the national party’s base and should be positively related to the measure of campaign activity.

A final attitudinal factor likely to affect campaign activity involves the rationale that activists had for seeking their current political party position. For many activists, the desire to take part in campaigns is a major reason why they decided to become part of local organizational efforts in the first place. For these individuals, we would expect to see a much higher rate of campaign involvement. To determine if there is such an effect, the survey asked respondents to indicate how important a list of reasons were to the “personal decision to seek your current party position.” Included among the many reasons was the following statement: “I see campaign work as a way to influence politics and government.” It is expected that those who identify this as an important reason will be more likely to engage in a greater number of campaign activities. Answer options were on a four-point scale and were coded from low to high levels of importance.

The third set of factors likely to affect campaign activity is a party member’s experience in holding public office. Activists who have served in an elected or appointed office probably have a higher level of practical knowledge concerning politics that can be brought to bear on their roles within the party. Activists with such experience are likely to have a greater stake in election outcomes and may have expertise that those involved in campaigns want to tap. For this reason, we expected that those who have held office are likely to be more involved in campaign activities, all other things being equal. Past office experience is measured using a dichotomous variable to indicate whether or not the activist reports having held an appointed or elected office.

In addition to past offices held, anticipated office holding is also examined as a possible explanation for level of campaign activity. Party members who report that they “expect to run for public office in the future” may be more inclined to take part in electoral activities since such experience may help them in their future endeavors. A dichotomous indicator is used to measure expectations about running in the future.

A final set of factors expected to influence participation in campaigns involves the characteristics of the activists themselves. Earlier it was shown that political party and position within the local organization (chair or member) affect the level of activity reported. In general, chairs are more active than members, and Republicans are more active than Democrats. Used as independent variables in a multivariate model, it will be interesting to see if these variables continue to have this effect.

Along with leadership position and political party, several other demographic characteristics of the activists are also examined. Age, gender, level of education, income, and racial characteristics are all included as independent variables. We know that voter participation is often affected by such features (Verba and Nie 1972; Rosenstone and Hansen 1993), and previous studies indicate that these factors often shape the involvement of party activists. For example, Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer (1998) found that females and those with higher family incomes consistently participated in a larger number of campaign activities. In addition, older party members participated in fewer activities, all other factors being held constant. Given the changing nature of party activists over the past decade, it will be interesting to see if such differences persist in 2001.

The effects of all these variables will be examined in equations separately for four categories of activists: Democrats, Republicans, chairs, and members. While all the variables are expected to have an influence within each category, the influence of many of the variables will probably play a larger role for members than for chairs. Because chairs of local organizations are already quite committed to their party’s effort (given their leadership role), we would expect the effects of most variables to have their greatest impact on rank-and-file party members.

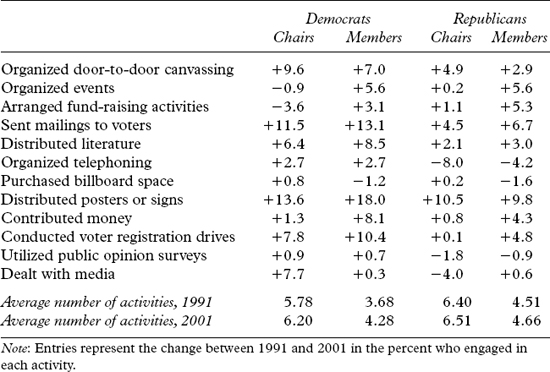

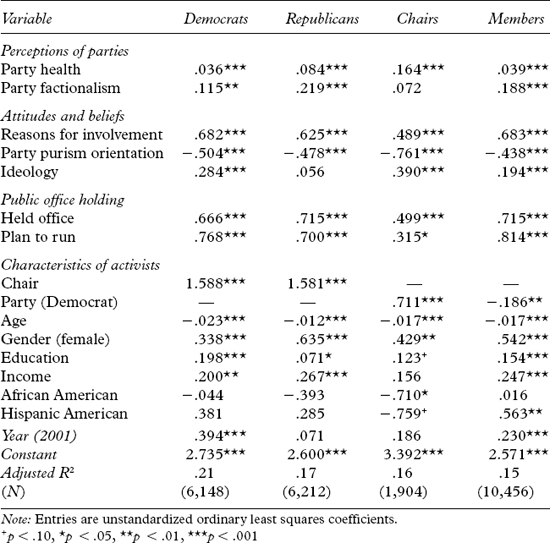

Table 11.3 provides the results of multivariate regression models separately by political party and by party position (chair and member) using data from the 2001 survey. These unstandardized regression coefficients represent the average change in number of activities performed by an activist for a one-unit increase in each independent variable. For example, among Democrats we find party chairs engaging in 1.594 more campaign activities than party members. Similarly we find among Democrats that a one-unit increase in the ideological score in the liberal direction (on the seven-point scale) results in a .285 increase in party activity (a little more than one-fourth of an activity). These coefficients allow us to determine the relative impact of the various factors.

As one can see, many of the variables have an influence in the manner that was anticipated. Among perceptions of the party, health has a positive influence on campaign activity. Where parties are viewed as strong, activists are more likely to take part in a larger number of functions. Party factionalism does not have a consistent effect across the categories of candidates. It is statistically significant for members and marginally so for Republican activists. However, its effects are in the opposite direction than what one might suppose. Such a finding is similar (although less strong) as that identified in previous analyses (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998). This result suggests that factionalism may stimulate some degree of competition for control of the party.

Among attitudes and beliefs, all three factors examined have an important effect on campaign activities. Those who became involved with party politics for the purpose of taking part in elections are, not surprisingly, more active in campaigns. The negative coefficient for party purism indicates that those with a pragmatic outlook on party politics are the members more likely to engage in campaign efforts. Political ideology also has an effect mostly as expected—those members whose ideology is closer to the base of their national party are more active in three of the four equations. However, this effect is present only among Democrats; for Republicans the coefficient is statistically insignificant and in the opposite direction. Why would ideology have an effect for Democrats but not for Republicans? It is probably because Republican activists as a group are more ideologically homogeneous than Democratic activists. For example, 53 percent of Republican activists identified themselves as “very conservative,” the most extreme ideological position on that side of the seven-point scale, whereas only 19 percent of Democrats put themselves in the corresponding extreme position (“very liberal”). In fact, 18 percent of Democrats said they were “somewhat conservative” or “very conservative” but only 1 percent of Republicans reported being in either “liberal” category. The greater variation among Democratic activists simply means that ideology has a greater potential to have an effect on their campaign activity.

Table 11.3 Factors Affecting the Extent of Campaign and Election Activities, by Party and Position, 2001

Moving on to holding public office, we find that both variables have an influence in three of the four equations. Only for party chairs do we not see an influence. Previous experience in public office increases the likelihood that members take part in election-related activities. In fact, just having a plan to one day run for office has a rather substantial effect on campaign activity. Perhaps these members are looking for practical experience that may assist them in their future campaigns.

Characteristics of party activists are also important predictors of campaign involvement. Given the earlier descriptive findings, it is not surprising that party chairs engage in a greater number of campaign activities. When holding constant so many variables, we find in both parties that chairs engage in about 1.5 more activities than members. What is surprising is that Republicans do not appear to be more active than Democrats. In fact, participation levels are actually higher for Democratic chairs than for Republican chairs (about one more activity reported on average). While such a result is surprising, it is consistent with multivariate findings from the 1991 survey that showed greater involvement for Democratic chairs. But the 1991 survey results also indicated that Republicans members were more active than Democratic members. In 2001 no such difference between party members is detected. Such differences suggest that Democrats have pulled even among members and stayed ahead among chairs in terms of overall campaign activities.

Several of the demographic features tested have an effect in a manner consistent with those found from the 1991 survey (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998). Similar to findings from a decade earlier, age is negatively associated with participation, while education, income, and gender (except among chairs) are all positively related. Whereas the 1991 findings showed lower involvement for African Americans in some areas, no such effect is identified in 2001. In fact, among party members, the coefficient for African Americans is marginally significant and positive, suggesting that African Americans may actually participate at higher rates than others.

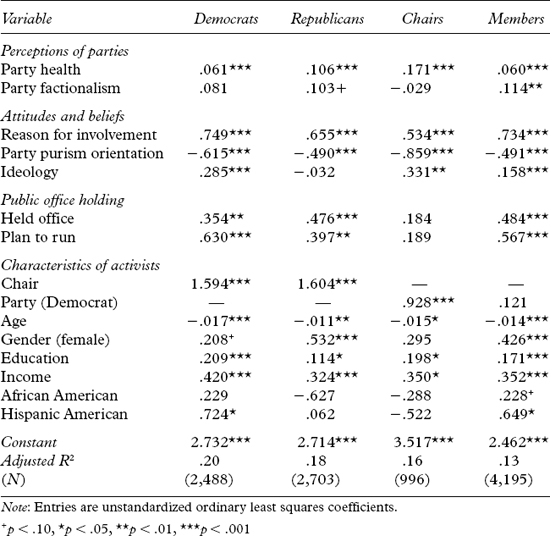

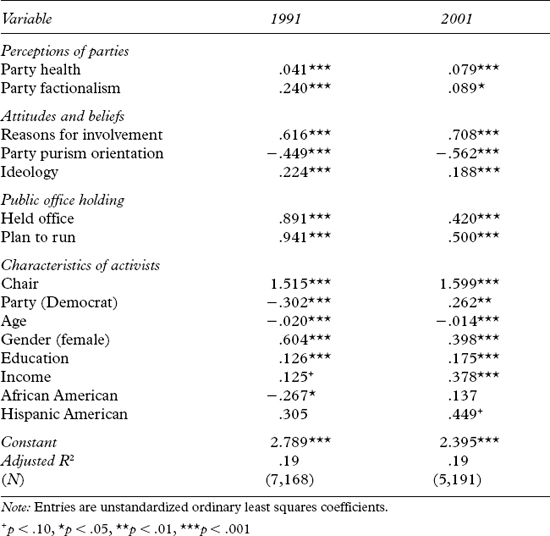

To gain a better sense of the different effects of these variables across time, an analysis using all the cases is conducted separately for 1991 and 2001. Here, political party and party position (chair or member) are included as independent variables. The results presented in table 11.4 illustrate that most of the variables have a similar influence across the two time periods. For most of the variables, the coefficients are all statistically significant and in the same direction. The only exceptions are for the effects of party and racial characteristics. It is clear from this analysis that Democrats were generally less active than Republicans in 1991, but ten years later this pattern had reversed. The statistically significant coefficient for party in 2001 demonstrates that a Democratic activist engaged in about one-fourth of an activity more on average than the typical Republican activist. Finally, there are also some differences over time for the effects of racial characteristics. Whereas African American activists engaged in fewer forms of campaign participation in 1991, by 2001 this difference had disappeared. And for Hispanic Americans where no differences in participation were found in 1991, by 2001 we see a positive effect for this variable (although the influence has only marginal statistical significance).

Table 11.4 Factors Affecting the Extent of Campaign and Election Activities, 1991 and 2001

A final perspective on changes in campaign activity at the grassroots can be obtained by conducting a combined analysis that incorporates survey responses from both the 1991 and 2001 surveys (see table 11.5). By including a dichotomous variable for year (1 = 2001, 0 = 1991), we can assess how time has changed the level of campaign involvement by political party and party position (chair and members). The results of these models demonstrate that when holding all the other variables constant, time does have an influence for some categories of activists. For Democrats, participation clearly increased over time, while for Republicans, their overall levels of activity stayed the same. Activity levels were similar in both time periods for the party chairs while individual members participated more in 2001 than in 1991. Such findings would appear to corroborate the comparisons made of the separate analysis that Democratic activists appear to have caught up to, if not overtaken, Republicans in terms of overall campaign activity.

Table 11.5 Factors Affecting the Extent of Campaign and Election Activities, by Party and Position, 1991 and 2001 Combined

Grassroots activists are at the front lines of a party’s efforts to win elections. This look at their role in political campaigns demonstrates that these workers engage in a wide variety of election-related activities. It is interesting to find that much of this effort involves the traditional party role in canvassing—distributing posters and literature, organizing telephone banks, and registering voters. In fact, much of the increase in activity over the past decade has been in such areas of traditional party work. These findings appear to contradict conventional wisdom that suggests modern forms of electioneering have become pervasive.

Many of the findings uncovered here are similar to those identified in data collected in the early 1990s (Clark, Lockerbie, and Wielhouwer 1998). Those who lead the local party efforts (county chairs) are far more involved than county committee members in most campaign-related activities, particularly those that can be considered managerial in nature. Also, many of the factors responsible for overall campaign effort are the same in 2001 as they were in 1991. For example, perceptions of party health and factionalism, attitudes about party purism, ideology, and many demographic variables have a similar influence across the two time periods.

However, some major differences were uncovered from the 1991 survey. Whereas Clark and his colleagues found levels of Republican activity to be greater than those of Democrats, by 2001 such differences had disappeared. In fact, among local chairs, Democrats were more active than their Republican counterparts. These findings suggest that Democrats responded to increased Republican efforts in the late 1980s and early 1990s with their own grassroots efforts to counter the successes of the Republican Party.

The findings presented here demonstrate that parties are alive and well on the local level and continue to play an important role in elections. The wide variety of activities engaged in by those at the grassroots will be a prominent part of the movement toward two-party politics in the South.

1. The question concerning the construction and maintenance of a campaign Web site was not included in the 1991 survey instrument, so comparisons on this dimension cannot be made.

2. Activists were asked to respond on a five-point scale from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree” to a series of statements about party activity. Four of the following statements were used in constructing the purism index: “Good party workers support any candidate nominated by the party even if they basically disagree with the candidate,” “Party organization and unity are more important than free and total discussion of issues that may divide the party,” “Controversial positions should be avoided in party platforms to ensure party unity,” and “Good party workers should remain officially and unofficially neutral in primary contests even when they have a personal preference.” Respondents expressing greater disagreement with each of these statements are considered “purists” while those expressing greater agreement are considered more “pragmatic” in their orientation. The response categories were coded 1 through 4 with 4 being the highest level of disagreement for each response. The measure was constructed by summing the responses and dividing by 4. The range of the resulting variable is from 1 to 4.