You can filter your AncestryDNA results to include only those in the same Migrations group as you.

I’m constantly amazed at how many genealogists have fully embraced using autosomal DNA testing for family history research. A lot of you not only have spit into a tube or swabbed your own cheeks, you’ve administered DNA tests for family members, too—in some cases, twenty or more.

A natural consequence of such autosomal abundance is that many of you are suffering from information overload. You have DNA results for yourselves, siblings, cousins, and even your in-laws. But what are you supposed to do with all that data?

First thing’s first: Stop and remind yourself exactly what you have and why. Your autosomal DNA is a mashup of about half of your mom’s DNA and half of your dad’s. But of course, since they got half from their parents, who got half from their parents, and so on, each person ends up with a unique mix of genes, pulled from a random assortment of ancestors. This biological reality reveals two important genetic genealogy concepts:

But not all DNA matches are made in genealogy heaven. As more folks test, your matches may be multiplying faster than you can analyze them. So as your family’s self-appointed DNA matchmaker, you need to determine which matches are worth focusing on. Here are three ways to identify your most-helpful matches and use them in your family history research—and a real-life example to show you how these strategies can point your DNA research in the right direction.

The first thing most people look at when they get their test results back is their admixture: the pretty pie chart that reports your percentages of DNA connected to various world regions. For the most part, these results won’t directly impact your family history research. The geographic categories are just too broad and too vague. But there are still ways you can use them to home in on your most-helpful genetic matches.

First of all, maybe you’re looking for ancestors of a specific heritage group, such as Jewish, American Indian, or African. If those places appear in your admixture results, you can take it as encouragement to watch for supporting genealogical records and connections. However, a lack of that particular distinction in your admixture results doesn’t mean you have no ancestors from that population. It just means that you didn’t inherit that particular identifying piece of DNA. If you think your family tree does contain ancestors of that ethnicity, consider testing cousins from the relevant family line. Start with the cousins in the oldest generation first.

Next, if your paternal and maternal ethnic heritage are very distinct (for example, your mom has all UK ancestry and your dad’s family is Italian and Greek), noting the origins of a match might help you more confidently place that match on one side of the family. While each testing company provides a limited view into the ethnic origins of your matches, MyHeritage DNA <www.myheritage.com/dna> does a particularly good job of displaying that information in a helpful way.

If you have less-certain ancestral origins, or your maternal and paternal heritages are less distinct (such as German and Central European on both sides), you’ll have a more difficult time utilizing admixture results for genealogy. But a tool from AncestryDNA <ancestry.com/dna> might come in handy. If you’ve tested there and been assigned to a Migrations group, you can use those results to help you find a particular kind of helpful match within your match list.

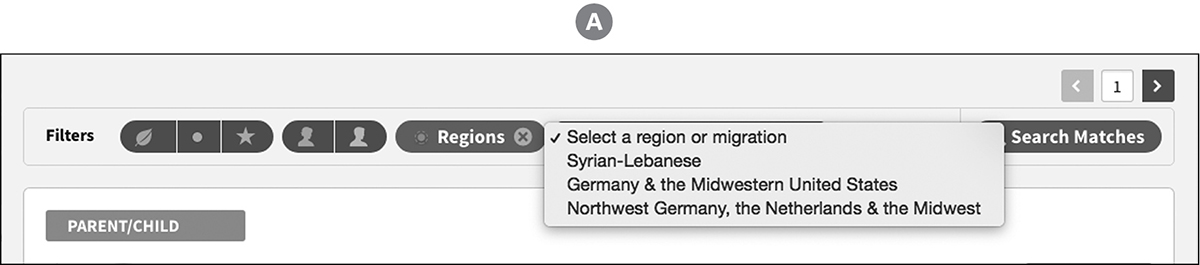

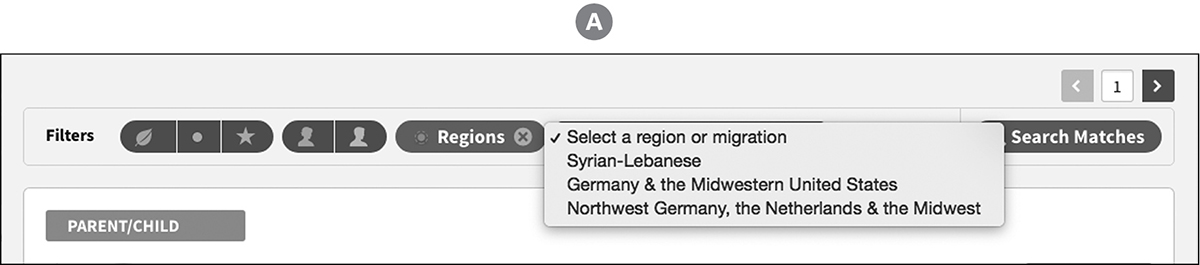

AncestryDNA’s Migrations are meant to show you where some of your ancestors were between 1750 and 1850. Assignment to these groups isn’t based on admixture results, but on the genetic interconnectivity of people in the database. To view only matches who share your Migrations, choose that filter at the top of your match page (image A).

You can filter your AncestryDNA results to include only those in the same Migrations group as you.

Theoretically, others in your Migration share ancestry with you via their ancestor who connects them to this community. So you may be able to identify your common ancestors if you both have only one line coming out of, say, Illinois. Multiple lines from the same place will be difficult to distinguish. Or the shared Migration group might be coincidental, with your genetic link lying in a different line.

As technology improves, however, Migrations will become more precise. For example, AncestryDNA might currently be able to place you in three different Migrations across the Midwest. That’s already pretty remarkable. Eventually, Migrations may further distinguish among those lines, revealing the Northern German, Southern German, and Germans from Saxony in your family history.

Testing companies offer analysis tools to help you determine how you’re related to your matches. For some tools to work, you first must add family tree information to your DNA profile. Each site has a different way to do this. On AncestryDNA and MyHeritage, create a family tree on the site (you can upload a GEDCOM), then go to your DNA page and link your DNA results to your tree. If you manage other relatives’ tests, you can link each one to a separate tree or to yours. At Family Tree DNA <www.familytreedna.com>, upload a GEDCOM and/or add family information under your account profile (choose Manage Personal Information, then Genealogy, then Surnames). At 23andMe <www.23andme.com>, you add details on ancestors’ birth dates and places. Then look in your DNA results pages for tools like these:

If you’re looking at a match estimated to be a fourth cousin, compare your list of surnames within the past four generations to that cousin’s. (Kudos if you know all thirty-two of those surnames.) If you’re lacking any surnames, you may still be able to make limited comparisons. For example, I know only thirteen of those thirty-two third-great-grandparent surnames on my dad’s tree. I can use those (and whatever surnames my matches have) to look for shared ancestors—or at least see which lines don’t connect us.

AncestryDNA, MyHeritage, and Family Tree DNA all try to help you find shared surnames in various ways—as long as you and your match both have provided public trees along with your DNA sample:

You also can search your match list for surnames appearing in family trees or information your matches have provided.

With the measly number of surnames I have on my dad’s side, I’m going to have trouble connecting with many fourth cousins on the basis of surname alone. So I can repeat the matching process for locations. To do this, make a list of all of the locations that appear in your pedigree chart at each generation. Then look for those locations in your match’s pedigree.

Currently, AncestryDNA offers the best location-specific tool. From your match’s profile page, click on the Map and Locations tab to see the places where you and your match both have ancestors. You also can search your match list for places in your matches’ family tree.

At MyHeritage, you can search your matches by country of residence and check for places of birth in linked family trees.

Again, location is helpful only if you and your match have some geographic variation in your pedigrees. I talked with a lady recently whose every ancestor five generations back was born within the same thirty-mile radius in North Carolina. So it may be easy to determine which line of yours she connects with (the only one from North Carolina), but identifying the connected folks in her tree will take a bit more sleuthing.

Even if your match hasn’t posted genealogical information, you may pick up some clues about your relationship from your genetics. All testing companies provide your total amount of shared DNA with each match. Shared DNA is measured in centimorgans (cM). A cM isn’t as simple a measurement as an inch or a centimeter, but it may help to think of it that way.

The more DNA you share, the more likely it is that you share a single, recent ancestral couple. Did you catch that? Single, recent couple. There are two reasons you can share DNA with someone. The first is that you actually share a recent ancestor. The second is that you both inherited a lot of DNA associated with your common ancestral region—but not necessarily from the same people. People from Ireland often have this problem, as do French Canadians and those with Jewish heritage.

At Family Tree DNA, MyHeritage, and 23andMe, look for the total amount of shared DNA on the main match page. At AncestryDNA, go to your match’s profile page and click on the circled “i” icon (next to the confidence interval) to see the total amount of shared DNA.

In general, those who share at least 30 cMs are likely to have a single recent common ancestor. Narrow down how you might be related to matches (and thus, which generation might contain your shared ancestor) by comparing your total shared cM with the ranges reported by documented relatives in the Shared cM Project. Learn more about this project and see a table of possible shared cM for each relationship in the sidebar or at <www.yourdnaguide.com/scp>. Which genealogical relationships best fit your shared genetics?

The Shared Matches tool on your DNA test website will revolutionize the way you do genealogy research. Seriously. Available in some form from all testing companies, this tool acts like a customized filter for your match list. It shows you only matches who share DNA with you and with one other match. There are two ways to use this tool:

A final word of caution: You and a more-distant cousin—say, fourth or fifth—may not share any DNA. (The Shared cM Project even shows that some known third-cousin relationships have no shared DNA.) That’s because you didn’t all inherit the same pieces of DNA from your ancestors. These cousins are still your cousins, but you wouldn’t know it from your DNA alone.

I’ll show you what I mean by applying these three steps to a research question from my own family tree. Who is Otto Murhard, born around 1825 to 1830-ish in either Germany or South Carolina (census records disagree)? I know about him only from his presence in records about his daughter Josephine, who is my ancestor. Here’s how I used genetic genealogy to investigate:

First, I applied ethnicity results. The ethnicity results I used are my father’s, to eliminate unrelated results I’d have from my mom’s side. On my dad’s tree are lots of folks from Virginia, the northeastern and midwestern United States, some England, one Denmark, and one Sweden. If the Murhards are from Germany, they’ll be the first Germans I’ve identified on my dad’s side.

Each of the DNA testing sites defines German ethnicity differently, both geographically and genetically. Why? Because their genetic data depends on the company’s particular reference populations, the group of people used to determine the genetic signature of an area. The company compares your DNA to its reference populations to determine your ethnic percentages.

23andMe, which lists German in its own ethnic category, says my dad is 9.3 percent French and German. AncestryDNA says he’s 42 percent Europe West. At Family Tree DNA, he’s 40 percent West and Central Europe. At MyHeritage DNA, he’s 88 percent North and West European. AncestryDNA assigns my dad to three Migrations, none specific to Germans. One of the Migrations, though, is specific to the southern United States.

What’s the take-home message here? Don’t rely on ethnicity results to direct your genealogy—just use them as a clue when you can. In the case of Otto, they’re not helpful.

Second, I looked at more-concrete genealogical information for my matches: surnames, locations, and genetics. Otto is my dad’s great-great-grandfather, meaning that fellow descendants of Otto would be my dad’s third cousins. Matches who are descendants of Otto or his wife, Johanna’s, parents would be my dad’s fourth cousins. I search my match pages at each testing company by surname first, looking for any other Murhards. I found no matches for that surname at Family Tree DNA, MyHeritage DNA, or 23andMe.

But at AncestryDNA, I found a fourth-cousin match who has a Murhard in her family tree. Let’s call this match Anne. From Anne’s tree, I can see she’s my dad’s second cousin, twice removed (abbreviated as 2C2R). That means they’re both descended from Otto, but there’s a two-generation difference between them. This brings up an important point about the difference between your genetic and your genealogical relationship. Their genetic relationship is fourth cousins: that is, they share approximately the same amount of DNA that typical fourth cousins share. But their genealogical relationship is 2C2R.

Once I found Anne and her Murhards, I explored her tree in detail. Sure enough, Anne lists Josephine, Otto’s daughter, as her ancestor. Then I needed to double-check that my genetic and genealogical relationships with Anne made sense. I clicked on the little “i” to see that she shared 61 cM of DNA with my dad. According to the aforementioned Shared cM Project chart, 2C2R share an average of 86 cM, with a range of 0–201 cM. So this match was in the right range. I definitely wanted to double-check the genealogical research that has led both Anne and me back to this ancestor.

Unfortunately, Anne’s tree didn’t have any more information about Otto and Johanna than I already have (less, actually). But now that I had a confirmed match back to Otto, it was time to employ the Shared Matches tool to find others who might share ancestry with both Anne and me. Remember, Anne’s matches could be related to Josephine (and therefore Johanna and Otto) or to Josephine’s husband, who was a Butterfield.

The Shared Matches tool brought up eleven people, including two second cousins with small or nonexistent pedigrees, and five third cousins. Trees showed that several of the matches were descendants of my Josephine, but they didn’t come up in my surname searches because they spelled Murhard with a t: Murhardt. (Note to self: The surname search in AncestryDNA isn’t nearly as forgiving as Ancestry’s record search is.)

A fourth cousin, P.H., didn’t have a family tree posted. However, when I clicked on his name, I found he did have a tree associated with his Ancestry account—it just wasn’t linked to his DNA test. That tree contained an Otto Murhard. It appeared that Otto was P.H.’s great-great-grandfather through a daughter named Caroline. If this was same Otto as mine, P.H. and my dad should be third cousins. But they only shared 39 cM of DNA, an amount that’s much lower than (but not completely out of range for) the 79 cM that average third cousins share.

A check of locations indicated that P.H.’s Murhard relatives were all in Oregon, where my Josephine was born. So now I had a name connection, a place connection, and a genetic connection—albeit one not as strong as I might like.

So what should my next step be? More genealogy research. I need to look for genealogical records that would connect my Josephine to P.H.’s Caroline. Were they sisters? I also could look for more genetic connections by exploring my Shared Matches with P.H. Unfortunately, most of those don’t have pedigrees. So I need to reach out to them and ask about their ancestors or encourage them to post trees online. The truth is, in genetic genealogy, you often spend time doing other people’s genealogy. And that’s okay.

As you can see, DNA testing hasn’t solved the mystery of Otto Murhard. But more—even better—matches may materialize on any one of my DNA dashboards any day. And meanwhile, thanks to these DNA matches and tools, I have more clues and confidence regarding my connection to Otto than when I started.

Diahan Southard is the writer and DNA expert behind Your DNA Guide <www.yourdnaguide.com>, a genetic genealogy consulting service.