2 More Than Romances

“I am a fotonovel, where all media converge, the newsiest novelty since the novel, and the comeliest since the comix. I speak all tongues and can tell all tales—in color!”1 These words are placed at the opening of Grease, the first of a series of paperback-sized photoromances based on Hollywood films and printed on glossy paper in a book format. Published in 1978 by Herb Stewart and his business partner Laszlo Papas of Fotonovel Publications, Grease employs for the first time in history the term convergence in reference to the photoromance. Despite Stewart’s claim in an interview with the Washington Post, however, it is not the first time that a film was used as a source for these adult comics.2 A small Italian publisher named Victory had already issued a fotonovel titled “La Valle del Destino” (The Valley of Destiny) in 1952, from Tay Garnett’s 1945 film The Valley of Decision with Greer Garson and Gregory Peck.3 After Victory’s first attempt, other obscure Italian companies quickly proliferated in the business of cineromanzi or cinefotoromanzi (from now on, cineromances), that is, weekly or monthly publications of photoromanced versions of films, both new releases and classics. Two main trends developed within the same market. The first was quality publications with bright, colorful covers that feature both frame enlargements and film stills, often in large format, intended to appeal to movie fans (figure 2.1). And the second was pocket-sized booklets of up to eighty pages, filled with hundreds of poorly printed and at times even blurred images, organized in regular grids and covered by substantial amounts of text, both dialogues and captions. Much in the same manner as exploitation cinema, in this cheaper format the cineromances milked the growing popularity of melodramas and pulp romances. Both familiar and obscure film titles appear in the list of printed issues, featuring recognizable taglines such as “In the Vortex of Sin,” “Deadly Seduction,” “Fatal Meeting,” “The World Blames Women,” “Love That Chains Us,” and so on and so forth (figure 2.2).4 Most of these small Italian publishers had franchises in France, where the same titles and the exact same photo-textual narratives were published, usually, within a few years (figure 2.3).5 By the end of the fifties, the genre had already disappeared in Italy, while it continued to thrive in France for a few more years, until the mid-1960s.

Figure 2.1

Cover of “Duello al sole” (Duel in the Sun), Cineromanzo per tutti, no. 8 (1954). Based on the film by the same title, dir. King Vidor (1947).

Stewart and Papas thus did not really invent a new genre but rather resurrected and refashioned an old one according to the tastes of American film buffs and comics lovers. Cineromances are not a completely new genre either, and instead perfect previous offerings in the realm of fan magazines. Interviewed for the Washington Post’s article about Stewart and Papas’s venture, Professor Jack Nachbar of Bowling Green University observes, “Movies and prints have been feeding off each other ever since comic strips and movies developed simultaneously at the end of the 1890s.” Before the emergence of the Italian cineromance, the U.S. magazine Photoplay (founded in Chicago in 1911) provided readers with the plot of one or more films, including some dialogues, and illustrated by still frames of significant scenes and stars. In France, there are examples of film novelization since the 1910s, which Baetens groups into three different formats: illustrated screenplays; illustrated or non-illustrated short story novelizations; and experimental filmic storytelling (figure 2.4).6 In Italy, the so-called cinenovella (film-novel) is introduced in the 1920s as a weekly or monthly issue complementary to fan magazines and other publicity materials such as fotobuste (medium-format publicity stills furnished with a minimal amount of writing) and posters, at the time of the arrival of the rotogravure in Europe from the United States, which allowed publishers to produce magazines at lower cost with many photographs of higher quality.7 However, when the cineromance was born in Italy in the postwar period, it emerged only formally from the tradition of film novelization, and was developed as a new niche market managed by publishers who did not previously invest in the cinenovella genre. In France, where the genre boomed only after the arrival of Italian imports, the established film-novel magazines such as Mon Film (My Film) shifted to the new formula and began producing their own photo-stories.8

At the core, all of these examples of illustrated film novelization serve similar purposes, as explained by Raffaele De Berti: to advertise films (inviting readers to movie theatres); to prolong the film-viewing experience (providing photographs of stars and reminders of key scenes); and even to substitute for it, in places where movie theatres were not available or among viewers who did not have the financial means to pay for tickets.9 In the context of 1950s Italy, the introduction of subscriptions in addition to sales at the newsstands meant a more capillary distribution. In some rural areas in Southern Italy, according to Italian director and cineromances collector Gianni Amelio, “there was no cinema, let alone a newsstand,” but thanks to home delivery, his mother (and he) could still get copies of cineromances, even in the remote Calabrian village of San Pietro Magisano.10 However, while for De Berti these are simply features of the mode of production, I agree with Leonardo Quaresima that they can also be considered clues to how film novelizations had functional value for their audiences—in responding to and satisfying their demands and interpreting their “voices.”11

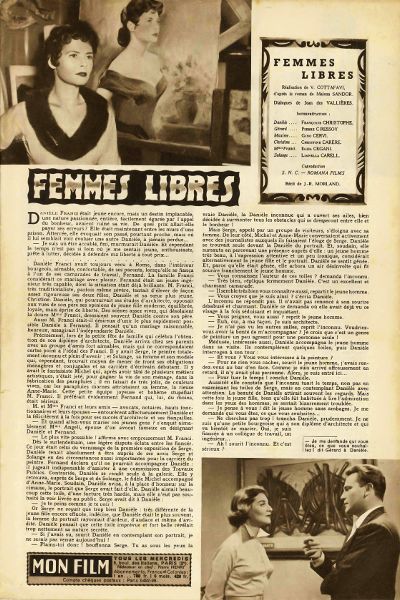

Figure 2.2

Cover of “Nel gorgo del peccato” (In the Vortex of Sin), I vostri film romanzo 1, no. 10 (1954). Based on the film by the same title, dir. Vittorio Cottafavi (1954).

Figure 2.3

Cover of “La femme aux deux visages” (The Two-Faced Woman), Les films du coeur 1, no. 7 (1959). Based on the film L’angelo bianco (The White Angel), dir. Raffaello Matarazzo (1955).

Figure 2.4

Example of illustrated short story novelization: “Femmes libres” (Free Women), Mon Film, no. 482 (1955). Based on Una donna libera (A Free Woman), dir. Vittorio Cottafavi (1954).

At the crossroads of national culture and foreign appropriation, cineromances (like fotonovels) epitomize the commercial nature of cinema and the role of film viewers as consumers. Hundreds of titles from small-budget Italian melodramas to Hollywood blockbusters and auteur films are published per year. As Giuliana Muscio highlights, these magazines eliminate the gap between “high and low, between independent and major.”12 Or, in the words of De Berti, film novelization is “a typical phenomenon of modern industrial culture,” a product of technological innovation and accessory to the development of mass consumption.13 However, neither Muscio nor De Berti further investigates the role that consumers played as active elements of the dynamics of production and distribution of cineromances.14 Also, neither is interested in studying how the gendering of the same audiences is constitutive of their business (and in this sense, fotonovels are different from cineromances, as I explain later). Muscio sustains that fan magazines stimulate film consumption but also foster a “desire for cinema, for stars, for stories and images.”15 In my view, to unpack the dynamics of such “desire,” that is, of the bond that ties female fans to the cineromance industry, also means to understand how these publications innovate the publishing market as (not despite being) feminine readings, in the wake of photoromances’ success.16

Cineromances look like photoromances (and often were referred to as such) not only in their style, but also in their approach to fanship and in the way they reflect a development of the Italian media system toward active consumption across media platforms; in this sense, the film-novel is a precursor to the cineromance since it also stimulates viewers to read and readers to watch. Furthermore, when talking about cineromances we can play with Jenkins’s idea of transmedia storytelling since printed magazines tell stories that branch from films and yet are not exactly the same (rather, they are unique extensions); they are meant to be autonomous points of entry in the narrative world (one can read the cineromance without having watched the film, and vice versa).17 Using the term transmedia storytelling rather than adaptation highlights the open flow between narratives (not their codependence) and often their concurrent production, as when cineromances are issued before or in conjunction with the film’s release. The narrative world in which printed illustrated stories and films coexist does not place them in competition or in succession, and each magazine opens up further possibilities for consumption, for example by means of previews of other films and magazine issues. Also, the construction of narrative worlds is fundamentally tied to individuals, that is, to movie stars who migrate from one medium to another, from the film to the cineromance, and from the cineromance to the magazine columns (and let’s not forget that often magazines published lyrics of the main songs in a film’s soundtrack, complete with all the information about the record label that produced them, thus creating further bridges with another industry). As I show in this chapter, these strategies of media convergence are gendered to maximize the products’ success and the effects are useful to further deepen our understanding of female fanship of this period. In particular, the relationship between a star’s images across platforms and her role as gender model for an increasingly modern female audience will be at the core of this chapter’s analysis.18

At the center of “the place where all media converge,” readers as fans build affective relationships to magazines, stories, and stars. These can be expressed in their loyalty as customers, and by the practices of religiously collecting each issue (like Amelio’s mother) or cutting out photographs (several secondhand cineromances that I collected for this project show evidence of this habit). Movies are turned into objects that fans can use to remember a particular scene or stare in awe at a star’s close-up, or sing their new favorite song, or read a film’s dialogue, reproduced often verbatim from the script in the balloons. Considering the relevance of participatory culture to editorial strategies, stylistic differences between series cineromances can thus be interpreted in continuity with the same practices of engaging readers across media platforms. While I will not analyze fotonovels in depth in this chapter, a few points can be made to exemplify how the format can be molded according to consumers. Grease experiments with uneven grids and is “littered with BOOM! TINKLE! sound effects” to appeal to an audience who appreciates the comic art (figure 2.5).19 In contrast, cineromances usually have regular layouts filled with a much more extensive use of dialogue and captions, a grid that will look familiar to any reader of photoromances (figure 2.6). Also, on the one hand, titles such as Grease, The Invasion of the Body Snatchers, and Close Encounters of the Third Kind suggest that the ideal buyer of fotonovels is not attached to a particular genre (or explicitly feminine labeled film genres such as melodrama), but rather is interested in movies with potential to attract a cult following. The same type of readers also would not mind that only a few titles could be published per year, due to the cost of copyrights and printing. On the other hand, cineromances are produced in high numbers and target a growing mass audience of female readers (and movie-goers) whose hunger for stories must be fed at a much faster pace (and it is already, thanks to photoromances).

Given the variety of magazines available on the market, it is important to not generalize the expectations of cineromance readers, to evade the trap of characterizing female readers according to traditional definitions of femininity. In this light, I disagree with Lucia Cardone’s overarching conclusion that in “becoming cineromances, films absorb the dark tones of the feuilleton, because they inherit the same [female] audience, passionate and demanding.”20 In my view, while Cardone correctly highlights the importance of reception in the production process, she homogenizes readers on the basis of the particular case that she is studying, that is, Victory’s “Catene amare” (Bitter Chains), which “photoromances” Raffaello Matarazzo’s L’intrusa (The Intruder, 1955) in a large format of I vostri film romanzo (Your Romance Films).21 “Catene amare” takes the appearance of a feuilleton because of the marketing goals of its publisher, I argue, not because of an established taste of a universal readership of cineromances. This is not a minor detail if we want to undertake a critical study of cineromances that ultimately sheds light on the role they played in Italian culture: (1) as national productions open to a transnational market; and (2) as commercial extensions engaging and exploiting audiences according to their tastes. In an op-ed on the first page of the 1954 issue “Le infedeli” (The Unfaithfuls), based on the 1953 comedy directed by Steno, the editor of Cineromanzo per tutti (Everybody’s Cineromance) Adelaide Marzullo explicitly addresses preconceived notions about readers’ expectations, the same ones that Cardone’s analysis takes for granted.22 Whether to openly challenge the dominant model of photoromance readers or to attempt to maximize the magazine’s profits, Marzullo announces that customers requested in their letters that more titles “other than romances” be selected for publication. In response, she claims, Cineromanzo per tutti promises to fulfill these requests and to continue to offer “photoromances of mixed genres” whose only constant feature will be the presence of “interpreti eccezionali” (exceptional movie stars). In support of this position, the article mentions other films “che non sono certo d’amore” (that are not really love stories) and have already been published by Edizioni Lanterna Magica: “Riso amaro” (Bitter Rice), “Don Camillo,” and “Pane amore e fantasia (Bread, Love, and Dreams).”23 To be fair, Cineromanzo per tutti and Cineromanzo gigante (Giant Cineromance) also publish numerous romantic plots and even turn films of a different genre into romances—for example, Alberto Lattuada’s Il bandito (The Bandit, 1946), printed with the title “Amore proibito” (Forbidden Love).24 However, the point here is not to deny that love relationships are a lucrative source of narrative materials for Lanterna Magica or to reject that many of its readers are indeed into romances. The question is that cineromances are not only (and not necessarily) about romances, both from the business point of view and from that of scholarship: their scope in content depends on their target audience and their place in Italian and global media cultures varies according to editorial strategies.25

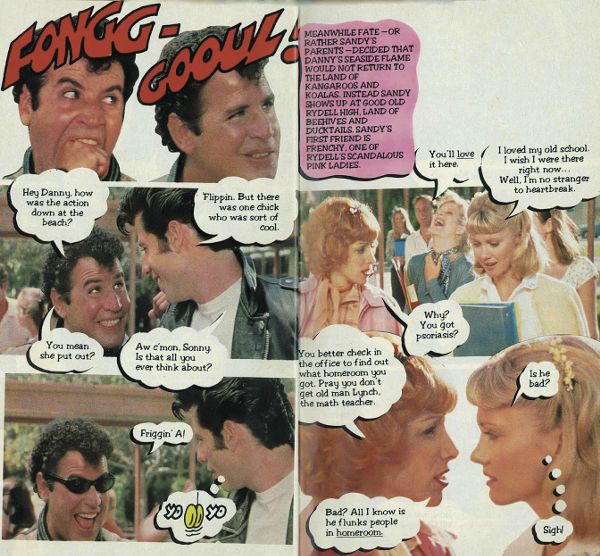

Figure 2.5

Grease (Los Angeles: Fotonovel Publications, 1978).

Figure 2.6

“Les Égoïstes” (The Egotists), Hebdo Roman 2, no. 51 (1957): 1. Based on Death of a Cyclist (dir. Juan Antonio Bardem, 1955).

A distant reading of magazines’ formats and titles could only get us a snapshot of an idiosyncratic business for a seemingly multifaced readership. In order to rigorously address the question of fanship, I argue that we must analyze in depth how specific series engaged readers’ participation and how each magazine exploited migrating stars and stardom. In this light, the rest of this chapter will focus on Edizioni Lanterna Magica and its Cineromanzo per tutti (Cpt) and Cineromanzo gigante (Cg) as media apparatuses of Italian entrepreneur Dino De Laurentiis. Building on the connection with the film industry, Lanterna Magica’s publications privileged star-driven movies across the blockbuster/art boundaries, from Senso (literally “Sensation,” but known in the United States by its original Italian title; dir. Luchino Visconti, 1954) with Alida Valli and Farley Granger to From Here to Eternity (dir. Fred Zinnemann, 1953) with Burt Lancaster and Debora Kerr, and provided readers with unique prints of still photographs from the set, both in medium and large sizes (figure 2.7).

De Laurentiis, who worked as agent for Lux throughout the 1950s on films such as Riso Amaro (Bitter Rice, dir. Giuseppe De Santis, 1949), was a typical figure in the context of the Italian film industry of the period, hired on a film-by-film basis and responsible for securing private and public financing as well as finding artists, in sum, to “package the unit.”26 As his career developed, his ambitions to become an international producer on the Hollywood model are evident, from the founding of the Ponti-De Laurentiis Cinematografica with its own production studios, in partnership with another Lux manager, Carlo Ponti; to his first big-budget movie Ulisse (Ulysses, dir. Mario Camerini, 1954) starring Kirk Douglas and Silvana Mangano; and eventually with the building of “Dinocittà” in 1959, at the same time in which Ponti sold him his part of the company.27 In addition to many Hollywood titles, Cg and Cpt published many films produced by De Laurentiis for Lux or by the Ponti-De Laurentiis Cinematografica.28 “Ulysses” is the first issue of Cg and came out on October 1, 1954, a few days before the film itself was released in Italy, on October 6.29 The announcement about the imminent publication of “Ulysses” appears in “Forbidden Love” together with an ad for Mambo, just one month after it was screened for the first time and only three months before the cineromance “Mambo” appeared in Cg.30 The first issue of Cpt instead is “Anna,” which also stars Mangano and includes the lyrics of “El Negro Zumbon” (also known as “Anna”) and “T’ho voluto bene” (I Loved You Very Much), the two songs in the film’s soundtrack produced by Edizioni Musicali R.P.D. (Radiofilmmusica Ponti-De Laurentiis).31 Further, an announcement on last page of the magazines brand all Ponti-De Laurentiis films for their indisputable quality: “There are SUCCESSFUL STARS, then there are SUCCESSFUL DIRECTORS, and therefore there are Production Companies whose success is guaranteed by the experience and excellence of its products. In Italy, this is the brand that labels all successful films PONTI-DE LAURENTIIS.”32

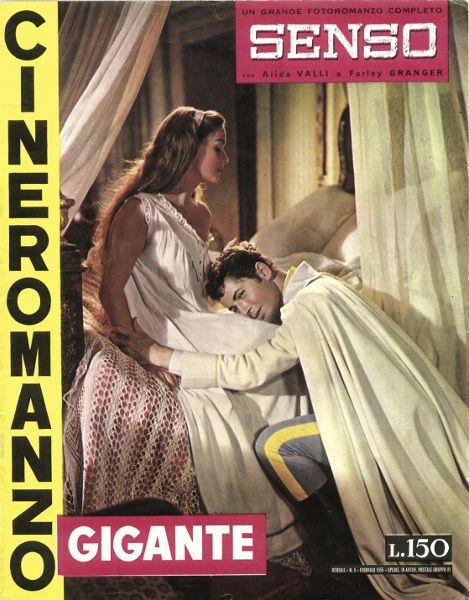

Figure 2.7

Cover of “Senso,” Cineromanzo gigante, no. 5 (1955).

From the point of view of media convergence, Cpt and Cg serve the purpose of creating connections with the other products of the De Laurentiis’ media franchise. What makes them so interesting with respect to fanship is how they promote celebrity culture. In particular De Laurentiis’ main actress and wife, Silvana Mangano, is a constant presence in the pages of the magazines, both in narratives and in columns. Her star persona, I argue, fosters her husband’s aspirations as media mogul. Although movie stars in Italy (and in Europe) enjoy the freedom of single film engagements, De Laurentiis’ personal ties with Mangano make space for an ambiguous long-term business relationship (longer than a typical five-year Hollywood contract), one that scholars have studied only to a limited degree, even though it was not an exception among Italian producers (as fictionally narrated in Antonioni’s film La signora senza camelie [The Lady without Camelias]).33 In my view, Cpt and Cg (and thus De Laurentiis) uniquely follow—in the Italian context—the Hollywood practice of exploiting publicity to match on- and off-screen images of a star, in this case Mangano, to create a persona that both fits the moral code of the industry (and in the Italian case, of society) and can please the star’s fans. Moreover, similar to photoromances, Cpt and Cg are marked as feminine on the basis of columns and advertisements that fill their pages: from “How You Can Become a Star” to “The Workshop of Ideas” and “The Housewife’s Notebook,” alongside commercials for beauty products, household necessities, and appliances. In this manner, potential readers of Cpt and Cg are indirectly represented as women in need of advice on how to be beautiful, fashionable, and efficient inside but also outside the home.34 Groomed by the agony aunt (aka advice columnist) and supported in her dream to make it in the film industry, this preferred reader has a passion for music and film entertainment, but also hopes to win the dowry offered as a prize to Lanterna Magica’s loyal customers. In this light, the still photographs and frame enlargements that compose the cineromances do not just retell a story, they also showcase the attitudes, poses, and expressions of a female star whom the same feminine reader can aspire to imitate. By promoting actresses like Mangano as successful both at home and in their profession, beautiful but also caring, attractive, and even provocative as much as lovable and modest, I claim that Cpt and Cg “contributed to the slow and difficult redefinition of women’s roles in Italy” by reconciling heteronormative gender models with the interconnected processes of modernization and liberalization of sexuality going on throughout Western Europe.35

Italian Stardom and Its Discontents

The physical appeal of Italian stars of the 1950s has been much discussed as well as exploited in both genre and art films, nationally and abroad. In Stardom Italian Style, Marcia Landy writes that beauty pageant contestants and film stars such as Gina Lollobrigida and Sophia Loren “were the vital signs of the coming ‘restoration’ of the erotic female Italian body to the body of film.”36 These bodies with “proper measurements,” Mary Wood highlights, were also the source of contradiction within film narratives that on one hand used them as signs of prosperity and, on the other, blamed them (and punished them) as morally corrupted.37 Stephen Gundle maintains that showing their bodies reduced Italian actresses to the lower category of “starlets,” for they would lose the aura of mystery and discretion that was proper to stars.38 The physical allure of Loren, Lollobrigida, Silvana Mangano, and Silvana Pampanini, among others, is a point of contention in film journals like Cinema Nuovo. Both directors and critics (including female journalists) argued that these women were harmful to Italian cinema (and to themselves). “It is sad to admit,” said Vittorio De Sica in an interview, “but the Italian film industry today exalts above all legs and prosperous bosoms.”39 According to the Editorial Board of Cinema Nuovo, “Our actresses, except for a few and in a few films (Magnani for example) are more beautiful than good.”40 “The Scandal of Body Curves,” as Cinema Nuovo called it, developed into a full-fledged reportage titled “The problem of actors [sic]: We want to go to school,” with contributions from film stars Lucia Bosé and Gino Cervi, among others.41 In this reportage, Italian actresses responded to the accusation that they lacked in skills (the “problem” mentioned in the title) by expressing their intention to attend school. Indeed, actresses themselves chastised the stars’ beauty, which was “more a sin than a gift,” according to Anna Garofalo.42 In fact, De Sica’s hypocritical judgment (the actor/director worked with both Lollobrigida and Loren after making that statement) cannot be separated from the director’s practice of hiring foreign actresses with the prospect of international coproductions. At the same time he was lamenting Italy’s lack of any real talent, De Sica was in London to sign a contract with Hollywood producer David O. Selznick for a film that could only have been made if it starred his wife the legendary Jennifer Jones.43 At the same time, on the very pages of Cinema Nuovo, the images of prosperous Italian actresses were both ridiculed and exploited. Summing up the contradictory position of the leftist journal, a close-up of Sophia Loren with a clear view of her breasts is accompanied by the caption: “Italian actresses, an American newspaper reads, are so beautiful that they do not need any talent to act.”44 The caption also introduces another aspect of the debate: even though the Italian stars are blamed for discrediting Italian cinema abroad, their sex appeal and the explicit display of their bodies constituted the backbone of publicity in the U.S. market.

In the press booklet of the movie Sensualità (literally “Sensuality,” but released in English as Barefoot Savage), for example, Eleonora Rossi Drago is advertised “in the tradition of Bitter Rice” as she joins “Italy’s top sizzlers.”45 While the booklet’s sensational language aims to “sell Drago as screen’s most exciting new star,” a 1956 episode of the popular television show What’s My Line? delivers in clear language how the American perception of Italian actresses was inscribed onto their bodies.46 In the episode, Mangano plays the “mystery celebrity” whom Bennet Cerf, one of the game participants, asks, after he discovers she is Italian: “Are you famous for various measurements?” Mangano and host John Charles Daly laugh at the question, while Arlene Francis comments off screen: “Aren’t all Italians actress famous for measurements?”47 So famous that film critic Edgar Morin, in 1957, would coin the term Lollobrigidism to indicate a “renaissance of the star system” in which the “the erotic recovery” plays a capital role.48

What is lacking in these discussions on Italian actresses is an inquiry not only into the role they played in the construction of their own images, but also into the influence that feminine audiences may have had in their making by the industry (both publicists and producers) through the course of the 1950s. Besides being sex objects for the male gaze, how did Italian actresses thrive in a market of consumerist culture that was increasingly made by women?49 In a 1996 study on “female images in Italian cinema and the popular press,” Luisa Cicognetti and Lorenza Servetti ask: “Why is it, that female spectators can be as fascinated as men by watching actresses who have no social existence, who are nothing but attractive bodies?”50 Cicognetti and Servetti argue that “the riddle” can be solved by getting out of the picture houses and looking at “popular film magazines:” “What was lacking on the screen, a social status, an interest in daily problems, child care, clothes and domestic worries, was to be found in magazines.”51 It was in Tempo, Oggi, and Epoca that women could not only see but also recognize themselves as both ordinary and outstanding.52 Citing the results of a survey published by Oggi, the two historians go so far as to argue that women were not that interested in stardom at all, since they did not answer the question in the survey that asked them who their favorite female star was. In a more recent article, Lucia Cardone denies such narrow interpretation of female characters in 1950s films and their appeal to Italian women, challenging the idea that they were simply attractive bodies and arguing that they were also a means to spread modern feminine figures.53 She also claims that cineromances (dismissed in previous studies) are the place where the images of women presented at the cinema are accessed by a much broader female audience. According to Cardone, cineromances are responsible for adapting female film characters to more traditional models of conduct, while still retaining the same appeal of transgression that the same characters have on the screen.54 Similarly, Réka Buckley contests the widespread opinion that female stars in the 1950s are only perceived as attractive bodies; rather, she shows that these stars are represented in tabloids as common women, particularly through images of motherhood and family life.55 Focusing specifically on Loren and Lollobrigida, Buckley convincingly demonstrates that off screen representations de-glamourize the stars, while still being anti-conventional enough to spread new models of womanhood. Whereas Cardone focuses on the images of women, not their physical embodiments in the actresses, Buckley’s account concerns only the star’s off-screen persona and does not analyze in depth the relevance of a star’s characters on screen. For example, Buckley mentions the scandal of 1957, when Loren married by proxy, in Mexico, Carlo Ponti, who already had a wife in Italy and was the father of two children. Loren, who started her career as an actress in photoromances, not only was Ponti’s companion but also a star for the Ponti-De Laurentiis company. She was particularly affected by the scandal even though she was not married at the time, and she was pictured in the press as the seductress. Buckley explains that, in order to counter public condemnation, Loren was instructed by publicists to build for herself in tabloids the image of a woman who cared for children and wanted to have some.56 Surprisingly, she only mentions in passing that the actress, after the scandal, also began to play motherly figures in her films as well. Instead, I see this as an important clue to understand the politics of the Ponti-De Laurentiis couple, who knew how to play the game of the star system.57

In sum, Cardone’s and Buckley’s accounts are important insofar as they make similar arguments that characters/actresses of the fifties presented models of womanhood that combined conservative and transgressive elements. However, their approaches keep the analyses of images and of stars compartmentalized. In the pages that follow, I demonstrate that cineromances in their twofold function of tabloids and storytellers suture the private and public images that hold together the star persona of Mangano on and off the screen. Through a horizontal study of cineromances as transmedia products, I show that the independent and sexually attractive characters that Mangano plays in films are imbued in their “photoromanced versions” by the features of traditional femininity that characterize her image in tabloids. I agree with Buckley that Italian stars in the 1950s generally had to be crafted conservatively in representations of their private-life events (above all motherhood). In addition, these stars had to deal with their own fame as seductress, promoted both nationally and abroad by the films in which they starred. Cpt and Cg aided publicists to assure that Mangano’s on-screen persona was not received at odds with her public face, by interpreting the inner feelings and motives of her characters in the captions. In this dynamic, columns in the same magazines are pivotal in building an understanding of stardom as based on hard work and moral integrity. Further, both Buckley and Cardone agree that some transgressive residues remain attached to the stars, despite the magazines’ or the films’ attempt to normalize their behaviors. In my view, the coexistence of traditional and modern characters is not contradictory or surprising but rather typical of the feminine figures that are prevalent in the current media culture, particularly in photoromances, and thus it is also fit to ensure Mangano’s success. Economic independence and physical beauty, dosed with self-policing practices of moral and social conduct, make “Silvana” an appealing model of modern woman that fit the consumer culture of potential customers of the magazines.

Lanterna Magica and Its Star: Silvana Mangano the Sizzling Housewife

In the 1954 Cg issue “Riso Amaro” (Bitter Rice), the “Corriere di Cinelandia” (News from Movieland) announces Mangano as winner of the “celluloid championship” also called “the chart of film stars.”58 She is ahead of Loren and Lollobrigida, according to the author, thanks to the huge success of Ulysses and even greater success of Mambo. The announcement should not be taken as proof that Mangano was indeed among everyone’s favorite stars. According to a recently published oral history project on moviegoers in the 1950s, for example, Mangano is rated number six, after Magnani, Loren, Lollobrigida, Yvonne Sanson, and Elizabeth Taylor.59 Whether we should trust more the memory of a sample group of film goers in Rome (both men and women) engaged in the project over the word of Cg is beside the point. More relevant is that the announcement “lies” in order to contribute to promote Mangano’s stardom, at the time of important De Laurentiis’ productions (either with Ponti or with Lux). In 1954, Ulysses was number one at the Italian box office, L’oro di Napoli (The Gold of Naples, also starring Mangano, in a minor role) was number five, however, Mambo was only number eight, negatively reviewed by critics, and definitely in need of some help to gain more profit.60 In fact, the whole issue of Cpt can be read as a well-orchestrated package that combines advertisement and storytelling to sell Mangano (and her films) to its readership. A photo accompanying “News from Movieland” shows a scene from Mambo with a caption that explains how Mangano’s films often feature “modern” dances: boogie-woogie in Bitter Rice, bajon in Anna, and now the mambo, whose choreography is directed by Katherine Dunham, a black dancer, choreographer, and anthropologist whose company had been touring in Europe since 1946.61 Meanwhile, the cineromance retells Bitter Rice with an emphasis on Silvana’s (the main character played by Mangano) act of repentance and faith in God, both of which are completely absent in the film. None of these details are coincidences, I argue, but rather fit in the industrial project of refashioning Mangano’s image throughout the 1950s. It was “una trasformazione programmata, studiata a tavolino” (a planned transformation, constructed on the drawing board), according to Giovanni Cimmino and Stefano Masi in their recent biography of the star.62 Not only did Mangano’s “planned transformation” concern the roles she played in film; rather, from a reading of the fan magazine Hollywood and Lanterna Magica’s cineromances, it appears to be a concerted publicity effort. In the pages that follow, I attempt to unravel the connections between Mangano’s private, public, and screen images, to those of the preferred feminine readers of Lanterna Magica.

Like other so-called maggiorate fisiche (busty women), also known for participating in beauty pageants, Silvana Mangano initially was promoted both nationally and abroad for her shapely figure and sex appeal; her body reflects, according to Landy and others, the ambiguities that characterized the country at a time of both restoration and modernization of society (similarly to how Richard Dyer interprets Marilyn Monroe’s in 1950s America, “in the flux of ideas about morality and sexuality”).63 The film that made Mangano into an international sensation was Bitter Rice, whose purported moralistic message clashed with the publicity that promoted Mangano’s voluptuous image. A moral tale embedded in Marxist ideology, the film casts Mangano as a rice worker by the same name, whose hard labor is exploited while, barely dressed when working in the fields, her shockingly beautiful body symbolizes the corrupting effects of mass culture (particularly American) and consumerism.64 But while most readings of the film highlight the contrast between the ideology of the narrative and the means of advertising (or the appearance of the female star), I am interested in the uneasy fit between Mangano’s image in this film and her image promoted in tabloids. After Lure of the Sila’s lukewarm reception, and at the time Il brigante Musolino (Outlaw Girl, 1950) was released, Hollywood published an article supposedly authored by Mangano herself, in which she opens up to explain how “three contracts” have fundamentally changed her life: the two film agreements signed with Lux and the private one that she ratified (the same year)—her marriage.65 Mangano speaks about herself with irony and candor, revealing her modest origins and her desire to work hard, her dream to marry, her fondness for a dog on the set, and her love and respect for both her father and husband. While to national and foreign audiences she was “l’atomica” (the Atom Bomb) and compared to Rita Hayworth, in the letter, the actress describes the hardship of working while battling with mosquitos in the rice valley during the shooting of Bitter Rice or the pain of wearing heavy boots in the wild Calabrian mountains on the set of Lure of the Sila. Soon after the publication of the Hollywood article, Mangano gave birth to her first child and, simultaneously, announced her decision to retire from acting. The news made a big splash in the press, across the European market of cineromances, and her claim that motherhood and family were more important to her than acting defined her off-screen persona throughout the fifties. In the words of Daria Argentieri, Mangano became “an actress despite herself, a star despite herself, admired despite herself.”66 According to a journalist in the French edition of “Anna,” a few years later, Mangano (who spoke French but not English) herself declared: “I have a vocation for motherhood, not for being a star.”67

Mangano did not abandon the profession, in fact, only her past image on screen. The act that seemed to denounce a fundamental gap between a professional life in the film industry and a private life in a traditional family was in fact just a turning (not an end) point in the star’s career.68 Several other articles from Hollywood after 1950 speak of Mangano’s new film roles as testimony to her professional skills as well as her moral stamina. In “Silvana’s Long Road from Riso amaro [Bitter Rice] to the Convent,” Giorgio Gaglieri argues that Mangano “did not want to convince critics and audiences by her beauty, but by her intelligence and perfect harmony with the character.”69 In Anna, the reporter adds, “Silvana Mangano will fully demonstrate her performance skills and her new image of femininity to everyone who remembers her sensuous and perverse in Riso amaro.”70 These features of strength and empowerment in the professional field are not opposed but complementary to her role as mother, as depicted in the press. Moreover, they are a model for aspiring female artists who want to harmonize their traditional views of gender roles with a successful career in the film industry. In “The Miss and the Trojan Horse,” Eligio Gualdoni presents the example of the changing image of Mangano into a lesson for her fans, who also dream about becoming stars by participating in beauty pageants.71 After the birth of her first child and her “scialba” (modest) performance in Lure of the Sila, according to Gualdoni, the “ex-miss” Mangano was now a different kind of role model: “her following two interpretations [Outlaw Girl and Anna] showed us a Mangano who has substantially changed: her beauty is not sexy and impudent anymore, but chaste, quiet, calming.”72 In the context of the ongoing debate about the lack of talent in Italian actresses, Gualdoni’s statements about Mangano are also a warning for fans who aspired to follow in her footsteps.73 The redeeming appraisal of Mangano for reinventing herself by showing her dedication to both the acting profession and family life is also an international advertising strategy. In a dedicated Spanish edition of “Colección Idolos del Cine,” the image of Mangano with short hair and in a turtle neck sweater attending to her small child on the cover is in line with her national picture, as well as the announcement, on the following page, that Silvana did not refuse to shave her head to play Jovanka in Jovanka e le altre (Five Branded Women, 1960), a role that Lollobrigida had rejected precisely for that reason.74 “Silvana did not waver,” says the article, “[she] showed up at Cinecittà studios the day after and handed herself over to the hairstylist.”75

In agreement with her newly gained maturity, Mangano’s film roles also change. A seductive and vindictive peasant in Lure of the Sila and a devoted partner and unwed mother in Outlaw Girl, Mangano in Anna and Mambo turns into an independent woman who ultimately decides to give up on romance and to devote herself entirely to a profession (nursing in the first case, dancing in the second), but not without a sacrifice. While in the first two films her character is morally ambiguous, in the last two she is literally split in two: a past and a present self. In both Anna and Mambo, Mangano is torn between two different life-styles, corresponding to different stages in the character’s narrative trajectory. In both cases, she eventually decides for a life spent in moral integrity and hard work. In Anna, she plays a nun and a nurse who was once a singer in a night club; in Mambo, a saleswoman infatuated with a small crook who becomes a successful performer in a dance company. Finally, Camerini’s Ulysses is the first film that fulfils Mangano’s other “vocation” on screen: to have children and care for them. In the film, she plays two characters: Circe the seductress and Penelope the mother. “Rare case for an actress,” one reads in CpT (1954), “[Silvana Mangano] will give birth to two characters who appear very different: as Penelope she will have to emphasize the virtues, the sweetness of a faithful spouse and as Circe she will be instead the sorceress who enchants men with her unsettling sensual charm, with her superhuman skills.”76 Strikingly, Mangano’s double performance in Ulysses is a reproduction of her twofold persona: the fantasy of Mangano on screen that is only in apparent contradiction with her image of perfect housewife in fan magazines.

Furthermore, in her roles Mangano transitions from “sex object to sexual subject,” to use Rosalind Gill’s expression, an idea that can best be exemplified by the different dance acts happening in Bitter Rice, Anna, and Mambo.77 From the boogie-woogie to the mambo, these dances have in common elements of transgression and exoticism, in Western countries, and they are attached to ideas of liberated sexual conduct. In the sexually repressive era of the 1950s, according to Jane Desmond, “[mambo] gave sexual expression and release in the culturally ritualized and accepted Euro-American context of ballroom dancing” and allowed “middle- and upper-class whites to move in what are deemed slightly risqué ways, to perform, in a sense, a measure of ‘blackness’ without paying the social penalty of ‘being’ black.”78 Dance scenes are signature moments in Mangano’s films and speak of her childhood dream, according to biographers, of becoming a professional dancer. They are also some of the most iconic images of her that still persist today in the cultural memory of moviegoers: Anna’s dance to the tune of “El Negro Zumbon” is featured in both Cinema Paradiso (dir. Giuseppe Tornatore, 1988) and Caro Diario (Dear Diary, dir. Nanni Moretti, 1994). The dance scenes in Bitter Rice, which take place in front of an improvised audience, feature Silvana “making a spectacle out of herself:” negatively connoted vis-à-vis both a leftist ideology and Catholic morals (she dances the American boogie-woogie and, in one of them, wears a stolen necklace), they can be ambiguously interpreted as an act of self-assertion or objectification, or both. In the words of Mary Russo, on the one hand, making a spectacle out of oneself can be perceived as a specifically feminine danger, risking exposure and ridicule. On the other hand, “the bold affirmations of feminine performance . . . have suggested cultural politics for women.”79 There is no room for ambiguity in Anna, instead, in which professional dancing is attached to a sinful relationship. In contrast, Mambo depicts Giovanna’s decision to enter Katherine Dunham’s dance company as a gesture of liberation from her sinful past; narrates the process of learning how to dance as an extremely strenuous process that requires incredible strength and dedication; and conveys the final commitment to dance as a long-term occupation through an act of selfless sacrifice that ultimately defines the character’s gained independence.

As the episode from What’s My Line? that I quoted earlier suggests, it may very well be that De Laurentiis and his company’s strenuous efforts to establish for Mangano the image of the perfect housewife and the exemplary professional did not work effectively in clearing her past of her sex symbol status. My point, however, is that by the time “Bitter Rice” is published, in 1954, the image of Silvana Mangano as the “hot sizzler” is clearly outdated with respect to her film roles and her public persona, as much as the attack on mass culture conveyed through her character in the same film is anachronistic. Modern dance is not a sin but a popular pastime (or as such is sold). And Lanterna Magica not only facilitated the spread of celebrity culture but also fostered readers’ aspirations for stardom: in each Cpt issue the column that hosted celebrities talking about their perspectives on “how to become a star” is always followed by a full-page announcement titled “our advice,” a contest for aspiring actors and actresses. Mangano thus functions as living proof that such aspirations are not in conflict but in continuity with traditional gender roles in the family. It is not surprising then that in the cineromance, three full pages are taken by the sequence in which Silvana dances the boogie-woogie in front of her coworkers and their male companions, each photo following her moves in slow motion, almost as if in a dance lesson. Over the photos, the captions strive to explain that while still provocative her dance is also a sign of “juvenile exuberance” and even “a voluptuous challenge to the misery that oppress[es] her fresh youth.”80 The message is the same as in favorable readings of photoromances, which aim to justify pure entertainment as social purpose. Further, the cineromance forgives Silvana for the murder and betrayal she committed in Bitter Rice, through a reading of the film’s ending that does not leave space for ambiguities (figure 2.8). Over a close-up of her face as she stares at the empty space in front of her, at the top of the tower from which she will jump, a caption states with compassion that “her face is scored with tears, tears of repentance, tears of pain; supreme offer to the compassionate God who forgives so much.”81 In the same close-up, Silvana asks God for forgiveness, an important addition to the film script that precedes the tragic ending only two photos ahead.82 As she lies dead in the field, another caption over a crane-shot declares: “She lies on the ground, immobile and her eyes open look again towards the sky as if she wanted to ask for help and pity.”83

Similar to “Bitter Rice,” “Mambo” heightens the moral dilemma faced by the main protagonist, played by Mangano, who must rely on her skills as a dancer to overcome the loss of her husband, and the betrayal of her ex-lover. Mambo was a critical flop, its melodramatic language criticized in reviews that considered the film no more than an “upscale photoromance.”84 Focused on blaming director Robert Rossen for a trite weepie, critics did not pay attention to the fact that, unlike current Italian melodramas, the female protagonist (Giovanna) eventually chooses her career over her lover. In making this choice, Giovanna also explicitly endows her female mentor and Pygmalion Toni with her success, rejecting her past in which she was completely dependent on men. Interestingly, the initial evaluation by the government office that supervised film productions had negatively judged Toni’s interest in Giovanna as interpretable as a lesbian relationship, and requested that the script be modified to clarify any confusion.85 I do not argue for a queer reading of the cineromance, however, I think that the emphasis on female mentorship is an important addition to the film that further completes the picture of the projected reader in the model of femininity constructed in the narrative. A one-page still photograph concludes the cineromance; in the film it appears more subdued, with a fade-out in black over the theater in which Giovanna performs, the caption stating: “Toni was right. It’s useless to look for our reality in others, outside ourselves. Nothing can be conquered with a strike of fortune and Giovanna is left with what cost her labor and sufferance. And, above all, love for her own skill” (figure 2.9).86 In the context of the magazine, these declarations are more than just an educational message of moral conduct; they are an advertisement for the profession, against notions of fame that come easily to attractive women. In the same issue, in the column “How You Can Become a Star,” Robert Taylor explains that the key ingredients to success are a positive attitude and, most of all, hard work.

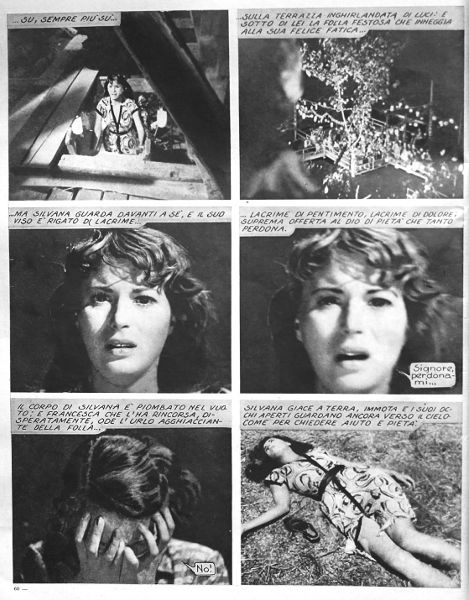

Figure 2.8

“Bitter Rice,” Cineromanzo gigante 2 (1954): 60.

As anticipated in the previously mentioned photo published in “Bitter Rice,” “Mambo” is also a way for Lanterna Magica to advertise the songs, and thus the dances, performed by Mangano together with Dunham, amid an already international cast of performers. Dunham was known for integrating her studies in anthropology into Caribbean and Brazilian choreographies and was the first to introduce Italian audiences to a company of mixed ethnic and racial groups. A comparison between the theatrical versions of the film in Italy and in the United States and the cineromance shows the extent to which the magazine aided the film’s promotion, nationally, while exploiting the global fame of Dunham and her choreographies.87 According to Dorotea Fischer-Hornung, American critics received the film negatively precisely because the dance scenes were “photographed so artily.”88 Comparison of the American and Italian versions of the film reveals that dance scenes are in fact considerably cut in the former and one, “La danza delle lavandaie” (The Dance of Washerwomen) is completely missing. In the cineromance, similar to “Bitter Rice,” photos of Mangano and Dunham dancing instead fill several pages in the story, including an entire grid dedicated to the practice session in the dance studio.89 In a way, the cineromance is faithful to the original script, which contains a special note regarding the editing of the scene at the dance school. “It must be clearly understood,” the note reads, “that this is not a montage in the ordinary sense of the word; pieces of it are, but more or less it is a series of vignettes which serve to illuminate the relationships of Giovanna to Toni, to Dunham and to the rest of the troupe.” Indeed, the technical means of the cineromance realizes precisely the very effect suggested in the script’s note: each still representing a pose and their sequence creating a grid that has no indication of temporal order. It is not clear from the script who would be the author of this note, but Dunham’s own vision of a “film di danza” (dance film) should be mentioned. In an interview with Glauco Viazzi in 1950, Dunham claims that her work in film did not yet satisfy her, since the director’s needs in the editing of dance scenes do not match with her vision.90 She also argues that she would like to direct her own film and that editing, above all, would be of great importance. Whether Dunham was also the author of the note in the script is not possible to say. However, it is evident that the cineromance as a form of storytelling is not simply a slavish copy of a film, but rather, an original text that interprets the expectations of readers (who are interested in the story but also in the dance moves) and, perhaps, the intentions of an artist as well.

Figure 2.9

“Mambo,” Cineromanzo gigante 4 (1955): 59.

The Question of the Cineromance

If the cineromance is indeed an original text, with its own style and content, it should also maintain its own rights as a creative work. In other words, the cineromance is not only an important tool for the industry, vis-à-vis other products, but also the fruit of artistic and intellectual labor, both individual and collective. On the one hand, the lack of declared authors and the fact that, as Baetens suggests, the cineromance depends on its audience seemingly make this idea quite absurd or even preposterous. On the other hand, given the strict correlation between the cineromance and the film, it seems legitimate to ask whether directors, writers, and stars were at all involved in the business and its profits. In fact, in the context of 1950s Europe, cineromances appear as hybrid objects in between commercial extensions and grassroots productions: another way to exploit films, in the hands of film producers; a means to make profit at the fringes of legality, for semi-industrial enterprises. With the exception of Del Duca’s Edizioni Mondiali, Italian companies involved in the business were not otherwise known in the publishing industry and it is possible that, in some cases, they even worked using pirated film positives. Ultimately, those who benefited from the unregulated commercial exploitation of films on paper were the fans, who had access to considerable resources of films that they could “read” from beginning to end—at least, as long as no one in the legal realm really paid attention.91 In the mid-1950s, the cineromance appears as a case under discussion in legal literature, more broadly concerned with the reform of the Italian copyright law of 1941, from which the photoromance was excluded. As I will discuss in the next chapter, Italian courts specifically began to question the role of film producers, writers, and directors with regard to authorship and the rights of economic exploitation of films. As both a derivative product of film exploitation and an original creative work, the cineromance constituted an aporia that needed to be addressed through legislation not only for economic reasons, but also to ultimately define the legal basis of film authorship, at the time of the “Golden Age” of Italian Cinema and of the French theories of the “politique des auteurs.”