3 Pirates of the Film Industry

“How did they get permission to make this stuff?,” asks Virna Lisi in Sfogliare un film (Browsing a Film), a documentary made in conjunction with an exhibition on cineromances held at the State Archives in Turin in 2007.1 The exhibition featured about two hundred issues, most of them from the private collection of Italian director Gianni Amelio, in addition to materials belonging to the National Museum of Cinema in Turin.2 “And how could we know? Do you think that they gave us something in return for these things? They didn’t even ask!,” says Lucia Bosè bitterly, a few cuts later.3 Taken aback or fascinated by a whole world of which they claim to be unaware, actresses Lisi and Bosè, and others (such as directors Mario Monicelli, Ettore Scola, and Dino Risi, and screenwriter Suso Cecchi D’Amico) realize that the makers of cineromances have tampered with their work, appropriated their lines, and used their images for commercial purposes. “I don’t know whether they could do that,” says Monicelli in reference to the producers of The Unfaithfuls (1953), which he co-directed with Steno.4 “What I do know,” he adds, “is that they made Steno and I, and all the cinematografari [directors] sign contracts at the time, in which we sold all copyrights for an infinite number of years, and for any kind of exploitation.”5

In the context of convergence, the issue of copyright is a relevant topic. Participatory culture can be exploited by the industry but also can backfire when fans appropriate products to the point of making them their own. Fan fictions and fan films are works inspired by other works whose copyright holders or creators may or may not welcome them, respectively, as the ultimate form of publicity or as intellectual property infringement. The low budget and rudimentary technology needed to make photoromances can foster these kinds of homemade products, as shown in Ennio Jacobelli’s practical guide for the production of a photoromance (Istruzioni pratiche per la realizzazione del fotoromanzo, published by Politecnica Italiana in 1956) and in Michelangelo Antonioni’s documentary film L’amorosa menzogna (Lies of Love, 1949). Ennio Jacobelli’s manual indicates that homemade products were at least envisioned if not realized in practice, although there is a gap between models and advice given in the book and the actual production process at work in the industry.6 At the same time, Jacobelli’s book supports an understanding of the medium as open to appropriation from below. Readers could take the opportunity given by the easily accessible means of production to create their own photo-stories, which possibly could then be sold to publishers. The handicraft quality of earlier semi-industrial enterprises defied the idea of standardization common to mass culture when fully developed. As shown in Antonioni’s Lies of Love, studios could be improvised in a working-class neighborhood. In one sequence, we see that a set could be built in the basement of any apartment building. In another sequence, we discover that when props are lacking, crew ingenuity remedies the problem: if there the champagne glasses needed for a scene are not available on set, they will be manually drawn on the photograph once it is printed. But while the example of artisanal enterprises of photoromances simply challenges the established world of corporate publishing, the making of cineromances pushes the legal boundaries by recycling images from existing copyrighted works. Only a few cineromance publishers have clear economic ties with producers (such as Lanterna Magica), and among the main players in the publishing industry only Edizioni Mondiali had its own series (Cine-intimità [Cine-Intimacy]). The other names in the business are small, unknown, and specialized companies that will last only a decade, until the early sixties, when the genre also disappeared from the market.

Browsing a Film indulges in conversations with stars, screenwriters, and directors without really inquiring into what seems a dubious industry at the fringes of legality. As I showed in chapter 2, films could be radically modified in their narratives when turned into photo-textual stories. The latter cannot be properly called fan fictions, however; as Leonardo Quaresima explains, they are the outcome of a process of negotiation between the “institution of cinema” and the “voice of viewers.”7 Further, whereas fan-made works in the digital age are increasingly under strict control of the industry at a global scale, cineromances in postwar Europe could take advantage of the ambiguities in place in the existing legislation in film copyright and the so-called legge per il diritto d’autore (literally “law for author’s rights” [lda]). Unlike the American system, film copyright laws in Europe take into consideration both the economic rights of producers and the moral rights of the “authors,” but without an agreement on whether the director should be the exclusive holder of the latter. In 1956, well-known legal expert Mario Fabiani argued that the cineromance constituted “a financially important phenomenon” that was “sometimes in violation of third parties.”8 Cineromances were not covered by the current lda, which was ratified in 1941, that is, a few years before the first photoromance came out in 1947.9 Therefore, the judicial challenge was to identify who are such “third parties” that could claim rights on cineromances, with regard to authorship or commercial exploitation. While film novelization in general is a well-established practice and complementary to the viewing experience, documents pertaining to the legal debate and lawsuits problematize historical accounts that treat cineromances simply as a means of publicity. As Lorenzo Gangarossa explains, “the judicial has supported the orientation in film criticism that recognized an almost exclusive ownership to the director in response to his [sic] predominant role, while in jurisprudence, the most accepted theories do recognize some prominence to the ‘Artistic Director’ but do not define him [sic] as author.”10

My claim is that an inquiry into the legal “question of the cineromance” is relevant to the study of European film history, in general, and of the Italian film industry, in particular. The expression questione del cineromanzo (question of the cineromance) is used by Amedeo Giannini in Il diritto dello spettacolo (Show Business Law, 1959), where he recommends that the lda be modified to include photoromances among the protected opere dell’ingegno (works of intellectual substance), in other words, because they qualify as intellectual property.11 According to Giannini, as well as to all legal cases, cineromances are not means of advertisement but rather works “of creative character, autonomous, and distinct from the film.”12 The discussion around the originality of cineromances is thus pertinent to the debate on film adaptation and authorship, in the context of European cinema cultures that are heavily based on the cult of directors and on the idea of cinema as an art, but are not homogenous with regard to legislation.13 The Berlin Convention of 1908 established that films are protected by copyrights, both when they are adaptations of literary texts and when they are original and creative works of fiction (documentaries are excluded).14 In Italy, the first official recognition along the same lines as the Berlin Convention was in 1925; however, the Royal Law number 1950 recognizes intellectual property but not the creative value of films. The lda of 1941 thus introduces for the first time, together with literary texts and music, le opere cinematografiche (cinematographic works) as creative works, but remains ambiguous with regard to ownership. To put it another way, the law does nothing but exacerbate the duality of films as both artistic endeavors and industrial products. Creativity is the basic element in a work that signifies the existence of an author, and the lda establishes the collectively creative nature of films whose coauthorship must be attributed to four individuals: the director, the soggettista (author of the story), the author of the music, and the screenwriter (in case of adaptation from a literary text, the novelist is considered the author of the story). Coauthors only hold moral rights, while producers have complete control over commercial exploitation.15 In particular, directors are excluded from any decisions made in the name of potential profit (including cuts made to the released version).

Including the photoromance under the lda would raise two questions: first, who can claim economic and moral rights to these photo-textual stories that, like films, are creative works but also mechanically reproduced and commercial products? And second, if modeled on the example of films, could the screenwriter and the director claim any rights to cineromances as “adaptations” of their own work? In the words of Monicelli, directors (as much as any other artists involved in film production) actually sold their rights at the contractual level and thus, they are like any other dependent employee.16 The claim that cineromances are independent and original works could reverse this statement to be used in favor of the artists. Directors could have sued publishers for not involving them in the making of cineromances because the work whose rights they sold in their contracts was limited to exploitation in the context of film-related publicity, not in a separate realm and market.

When looking at the specialized literature, there are no discussions about cases of lawsuits initiated by directors in Italy (Gangarossa’s only reference is a 1950 trial in Paris). Instead, I found a few instances in which actresses sued publishers for using their images in cineromances, which are specifically based on the claim of originality. Notably, the lda does not take film stars into consideration at all, even though in the early years of narrative cinema they are considered fundamental to the making of a film, and their performances constitutive of the work of art.17 Actors and actresses are the main commercial drive of the entire business of both cinema and cineromances, and yet, they are legally just like any other employed worker. In his account of the “safeguarding of the image of the film actor in the rendition of the film in the form of a photoromance,” Vittorio Sgroi explains that “actors do not create, they execute.”18 An Italian judge and legal expert, Sgroi refers in this quote to a case from 1955, when actress Benedetta Rutili filed at the Rome Court a lawsuit against Gino Rippo, director and producer of Ho pianto per te (I Cried for You, 1954). According to Sgroi, Rippo made an agreement with the publisher of Le grandi firme dello schermo (Signature Films) for a cineromance by the same title, featuring thirteen photos of Rutili as supporting actress. Rutili challenged Rippo on two related fronts: first, whether the producer had the right to use the actress’s image without her consent; and second, whether this particular use of her photos (i.e., in a photoromance) was also detrimental to her image and career. The Rome Court acquitted Rippo on the basis that the cineromance is not “a rendition of the film” since it has additional and original elements, “qualitative and quantitative.” Because the actress is not considered a creative contributor of the film, Sgroi explains, she cannot claim any rights over the use of film materials for another work.19 In other words, the argument of originality is used against the actress, who would only be reimbursed if indeed the cineromance were a commercial extension of the film, not a unique adaptation. Further, the ruling agrees that “by acting in photoromances, [Rutili] could be stopped on her path toward fame.”20 However, the cineromance is too close to the film to really constitute such threat.21 Finally, Sgroi argues that whereas there are norms that discipline the use of personal images, film stars constitute the exception to the rule because of their notoriety, which justifies the audience’s demand to see their “effigie” (likeness): celebrity implies a silent agreement between stars and their fans on the use of their photos for publicity. In Sgroi’s words, “The film star cannot invoke a right to privacy like any other individual.”22

Ultimately, Sgroi’s report and interpretation of Rutili’s case reiterate discourses to which I referred throughout this book: photoromances are products of low culture, stardom is a profitable condition that comes at a personal price. Comparing this case to that of Lucia Pasini in 1962, however, we can see fluctuations throughout the decade in the articulation of the same discourses, despite the fact that the lda was never modified during this time. According to the daily newspaper Corriere d’informazione, Pasini (mother of actress Luisa Ferida) sued and won a case against publisher Victory for the illegal publication of two cineromances based on two films in which her daughter performed the leading female role, La bella addormentata (Sleeping Beauty, dir. Luigi Chiarini, 1942) and L’ultimo addio (The Last Goodbye, dir. Ferruccio Cerio, 1942).23 Giovanni Ponzoni, Victory’s legal representative, sustained that the publisher bought rights from producers Cines and Alan Film, in agreement with the lda, which did not presume any additional compensation for the stars. Ponzoni also argued that Ferida’s mother did not submit her daughter’s contracts, so that it could not be proven on paper that there were any limitations to the economic exploitation of the films. By comparison to other current contracts of the period, it would be fair to agree with Ponzoni, since most likely producers had reserved for themselves all rights of use of the star’s image. These circumstances notwithstanding, the Rome Court ruled in favor of Pasini. As opposed to Rutili’s case, the same consideration that cineromances are separate works, not commercial extensions of the films, is used to argue that to publish them without the actresses’ consent and compensation was illegal. Given that the lda. was not modified between the Rutili case and the Pasini case, why would the court rule differently? It is noteworthy that cineromances disappeared from the market around the same time Victory was found guilty. Whether the events are connected is impossible to claim for sure. However, the case of Pasini testifies that changes in place in cinema culture may have affected judicial interpretations of the star’s rights of ownership of her image and work.

The Illegitimate Girls of Sanfrediano

Before Pasini and Ferida’s case, the most advertised legal battle against a publisher of cineromances involved a well-known novelist, Vasco Pratolini, whose book Le ragazze di Sanfrediano (The Girls of Sanfrediano, 1949) was adapted into a film in 1955, directed by Valerio Zurlini and produced by Lux.24 In 1956, the Florentine newspaper La Nazione announced that Pratolini won a lawsuit against Lanterna Magica over the use of his novel to make a photoromance.25 The cineromance titled “The Girls of Sanfrediano” was issued in May 1955 in Cineromanzo gigante, a few months after the release of the film. The first page of the cineromance quotes both the film and the novel as sources: a list of the film’s cast is introduced by the sentence “loosely based on the story by Vasco Pratolini of the same name—Edizioni Vallecchi” and the name of the author of the “photoromanced version” (Maria Baldeva) is placed at the end, after the sentence “A Lux Film,” printed in a larger font.26 Lanterna Magica’s common practice to include the name of Baldeva as the author seems to sustain Pratolini’s claim that the cineromance is “a work of creative character, autonomous, and distinct from the film” and thus, as the novelist whose work was adapted in the illustrated magazine, he had right to be informed (and paid) prior to its publication.27 Incidentally, the name of the Florentine neighborhood in the novel’s title (Sanfrediano) is spelled the same in the cineromance (“The Girl of Sanfrediano”) and differently in the film’s title (The Girls of San Frediano).28 The publisher’s lawyer argued the opposite, that the cineromance “was taken not from Pratolini’s story, but from Lux’s film, which had authorized the publication as means of publicity for the film itself.”29 In addition, according to Lanterna Magica, “publishing a photoromance with content analogous to its film version, utilizing the frames and dialogues of the cinematic work, falls within the power of economic utilization of the film and constitutes, in a way, a natural form of exploitation of the film itself.”30 The production company then provided witnesses to prove that “it is custom for film producers to distribute photoromances, obtained using the frames and dialogues of the film, without asking for authorization from the author of the literary work from which the film is taken.”31

A habit that did not, in any case, justify the crime, since the Rome Court eventually agreed with Pratolini and stated that the publication was “illegittima e abusiva” (illegitimate and unlawful), additionally asking that the verdict be published in the newspaper Il Messaggero at Lanterna Magica’s expenses.32 It is worth quoting the report at length:

The law regarding the author’s right does not consider, within the protected works, the photoromance. Now, the cineromance, whose diffusion, especially in Italy, is resurging in recent times, constitutes a fictional creative work [creazione della fantasia] and has a form of representation all its own, even though it lacks artistic intentions and targets a certain social strata. The cineromance results, in fact, from the combination of photographic and literary elements and represents factual content through the succession of photographs, reproducing characters and environments of fables. [These photographs are] connected by a literary element and vivified through reproduction, in written word, of the dialogues between the characters represented. Because of the elements of which they are composed and the unique form of representation, the photoromance clearly distinguishes itself from the literary works and from the cinematographic works and qualifies without a doubt as a category of work all its own. On these premises, it appears evident the groundlessness of the thesis according to which the photoromance would not constitute as anything other than a form of representation of the cinematic work. This [a film], indeed, has as a proper form of representation only that of the projection on the screen and not also that of its printed publication, which is, instead, properly of literary work and, as is seen, also of the photoromance.33

The verdict uses the term photoromance, bypassing the fact that photographs are captured from an existing film reel. It also expresses the idea that, because of the support material (paper), photoromances have more in common with literary texts than with film, even though they cannot be called works of art. As I explained, artistry or creativity are not necessary elements of intellectual property; most relevantly, the point made about the target audience confirms, similarly to the case of Rutili, that the Rome Court agrees with an understanding of photoromances as low culture. In this sense, the sentence in favor of Pratolini does not aim at the inclusion of photoromance in the lda but rather conservatively at protecting the novelist against the cultural industries, which exploit and popularize his work. Competition is tough, explains the article, “especially in the social category addressed by photoromances, having the possibility to choose between the original work and the photoromance, many people evidently would give preference to the latter, with indisputable prejudice for the author of the original work.”34

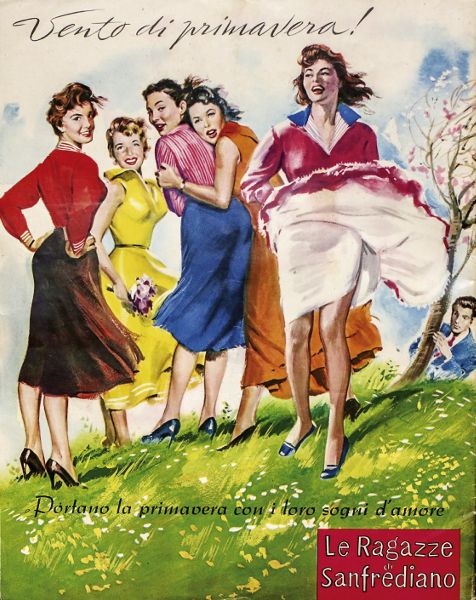

In addition to making the verdict an exemplary case to be published in national newspapers, the Rome Court ordered that all copies be destroyed. Clearly, the court’s order was only partially successful, since some copies still exist. As I write, I have in front of me the brightly colored cover page of “The Girls of Sanfrediano,” showing the faces of its protagonists: Antonio Cifariello, Rossana Podestà, Giovanna Ralli, Marcella Mariani, Giulia Rubini, and Corinne Calvet (figure 3.1). From a close reading, it seems clear that the Rome Court’s decision to eliminate all copies respected Pratolini’s desire to maintain the authenticity of his novel when confronted with a product that substantially modified the original. Similar to the film, the cineromance’s distinctive entertaining quality is in opposition to the book’s educational message and goal of social investigation. In its representation of female characters, Lanterna Magica’s publication is also closer to the commercial world of photoromances than to the leftist culture of Pratolini’s novel. “The Girls of Sanfrediano” opens with a dedication to the girls who live in the working-class Florentine district of Sanfrediano: a “mondo a sè” (world of their own) where they “work and love, are sweet and noisy, tender and feisty, shameless and faithful.”35 The back cover further emphasizes the centrality of female characters in the plot, by presenting a drawing in which five young women (vaguely resembling the five actresses who play the protagonists of the film) are standing together at the top of a green hill, while a young man looks at them from far away, hiding behind a tree (figure 3.2). The drawing is reminiscent in style of Grand Hotel’s graphic artist Walter Molino. Text at the top of the page reads “Spring winds!” and at the bottom: “They [the girls] bring the springtime with their dreams of love.”36 In its design and captions, this page encapsulates the feminine gender model that I have discussed at length in this book, each “girl” embodying in her individual characterization an idea of femininity as both traditional (branding feminine beauty as a tool for success) and liberated (seemingly embracing sexual attractiveness as empowering rather than objectifying). Tight skirts and blouses, high-heeled shoes, and bright makeup enhance their bodies as they fearlessly gaze straight at the reader. The “spring wind” lifts one girl’s dress, revealing her knees and underskirt, as she smiles untouched by the event (while a man hiding behind a tree widen his eyes at the scene). In this sketch, exposed on the back cover of a popular magazine, readers may find an enticing model of female emancipation, carefree and full of pleasure.

Figure 3.1

Cover of “Le ragazze di Sanfrediano” (The Girls of Sanfrediano), Cineromanzo gigante, no. 9 (1955).

Figure 3.2

Back cover of “Le ragazze de Sanfrediano” (The Girls of Sanfrediano), Cineromanzo gigante, no. 9 (1955).

On the contrary, Lux’s film focuses on the male character as protagonist and begins with an overlay text superimposed on the images of a young man on a motorbike. The text explains that, since Robert Taylor appeared on the screen, all attractive young men in Florence are now called “Bob” and that the film is dedicated to these “poor boys, innocent victims of their charm.”37 Bob is the nickname name of the protagonist, Andrea Sernesi, a modern Casanova who has sentimental relationships with different girls at the same time, until one of them discovers his ploy and eventually leads him to his demise. A typical masculine figure of Italian comedies of the fifties, Bob speaks to a postwar masculine audience who could relate to the projected image of ineptitude of the main protagonist whose multiple attempts to catch a girl are never portrayed as predatory behavior. Screenwriters Piero De Bernardi and Leonardo Benvenuti are more or less faithful in their rendition of the novel’s plot, but make an important modification to its ending, which reflects the overall lighthearted look at Bob’s “weaknesses.” According to a reviewer in L’Unità, by comparison to the novel, the film lacks the critical view that is expressed in the book’s finale.38 In the novel, the six girls eventually play a terrible prank on Bob to vindicate their honor and dignity. Afterward, Bob repays his debts by doing what was expected of him as a man in a patriarchal society, that is, he marries one of the girls (Mafalda). On the contrary, in the film, no revenge takes place and Mafalda leaves to work as a dancer. Bob’s multiple love affairs, presented uncritically as comic plot devices, are not punished but rather are forgiven, and the possibility that the same story will continue remains open. Cineromance and film are in this respect similar not only because they literally close in the same way, but also because they lack any moral judgement. Neither forces Bob (or the girls) to comply with traditional gender models and start a family. Once his unfaithfulness and ploys are uncovered, Bob is left alone and, in both the film’s and the cineromance’s final scene, chased by his big brother who will beat him up “until the end of the world,” in the words of the voice-over narrator (and of the caption): a closing scene that resembles those in the commedia dell’arte, in which the story frequently ends with a never-ending brawl at the expense of Harlequin.

What is remarkable here is how the finale challenges the suggestions made in the documents of the Commissione di revisione cinematografica (Film Revision Committee), later a section of the Ministry of Tourism and Culture.39 The Law Decree ratified in 1947 (Legge Cappa, no. 379) created this committee to evaluate proposals seeking government funds and to control their national and foreign distribution. In order to receive financial support, producers were obliged to present (in pre-production) a synopsis to the committee, as well as the list of cast and crew. The committee then decided whether to grant approval for the film’s release (nullaosta) and export. A document dated May 22, 1954, reveals that The Girls of San Frediano was supposed to end with the girls’ prank on Bob, which the committee criticized for its dubious moral message. Its report invited the film’s director to reinterpret the screenplay in a “moral” way.40 On July 7, 1954, when the film is already in its final version, a second report makes no mention of the ending but only requests elimination of colloquial language considered vulgar.41 However, a new ending appears in the duplicate of the nullaosta (authorization of screening) issued by the Undersecretary of State and approved on December 23, 1954—five days before the film’s theatrical release. According to the authorization, “In the end, we see Bob married and dealing with the serious issues of family life.”42 How did Lux manage to release a film with a far less conservative statement about Bob’s love escapades, even though the authorization clearly states that no modifications should be made to the storyline? The film’s ending is more in line with the kind of comedies to which most viewers were accustomed, and potentially more successful. Also, the cineromance’s similar ending should have raised the same moral concerns. The case of “The Girls of Sanfrediano” thus goes beyond the juridical debate on the legal status of the genre, and into the realm of governmentality.

What if at the core of legal opinions on the cineromance was not the validation of the artists as copyright holders, but rather, the need for normative rules that could extend the disciplining power of government apparatuses on mass culture? The moral concerns regarding the film occasionally slipped through the net of the Film Revision Committee while cineromances were regularly unsupervised in their adaptation of movies for the popular press. To be fair, publishing was also under the scrutiny of government censorship in matters of moral content, however, not in the same capillary manner as cinema.43 And yet, photoromances are potentially as “dangerous” as films because of their wide popular audience, their visual language, and the narrative treatments of topics concerning social and sexual behaviors. To go back to Quaresima’s point on the grassroots basis of fan magazines, the “institution of cinema” is a complex system involving audiences, artists, the industry, and the government; therefore, cineromances are the products not only of compromises between perspectives inherent to the films and those of viewers (their expectations, lifestyles, social rules, and literary preferences), but also of the private and public bodies involved in their making and distribution.

Indeed, a second aspect that is relevant to the “question of the cineromance” is the extent to which the “archontic” process of remaking film narratives in the murky waters of Italian copyright legislation also had the positive outcome of eschewing government censorship, as well as the control of producers, to the benefits of consumers.44 By the attribute “archontic,” I mean that we can understand the relationship between films and cineromances as a form of retelling that expands the textual archive. In particular, close readings of contested films reveal that sequences or images removed at the behest of the Film Revision Committee, or cut by the producer for commercial reasons, or as a practice of preemptive self-censorship, can be found in cineromances, albeit decontextualized or overwritten by captions. These “rescued” images are perhaps not necessarily supporting radical positions; yet, they challenge the moral boundaries set by the government and the industry, as well as give us access to lost frames of film history.

At the Margins

In 1952, Vittorio De Sica corresponded extensively with the General Command of Carabinieri corps to ask permission to shoot “as a background, barely seen through the glass doors, the arrival of the head of State with the honorable security detail of Cuirassiers Regiment” (Carabinieri are the national police of Italy and a corps of the Italian army; the “cuirasser” is a type of armor).45 The scene is part of the film Stazione Termini (Terminal Station, 1954) and the so-called “background” is in fact a main feature of De Sica’s style (and of Cesare Zavattini, the screenwriter): a look at the everyday life of travelers that socially grounds the story of two lovers meeting, for the last time, in Rome’s main train station. In fact, in order to make the scene look real down to the smallest detail, De Sica wrote directly to the Ministry of Defense (via lawyer Randolfo Pacciardi) to ask for a set of original cuirassier uniforms promising that “the film is inspired by decorous and aesthetic principle and the cursory use of this shot cannot in any way damage the righteous fierceness and utmost dignity of the Cuirassiers Regiment.”46

The extremely pompous statements that De Sica signed for the sake of creating this sequence cannot be understood outside the context of postwar Italy, where cinema was under tight government control, particularly concerning representations of the Italian army. The most clamorous case took place in 1953, when director Renzo Renzi published in Cinema Nuovo in collaboration with its editor Guido Aristarco a film project titled L’armata s’agapò (The Love Troops, from the Greek verb agapò—love) about the Italian Fascist occupation of Greece. Renzi and Aristarco spent forty days in a cell and were then punished to a few months in prison for the crime of contempt of the armed forces (the so-called vilipendio). Carefully measuring his words, De Sica’s goal is to get hold of official uniforms without compromising the film itself. Indeed, Terminal Station does not in any way comment directly on the carabinieri or any other corps, neither in this scene nor in others. The same could not be said about the cineromance “Stazione Termini” (Terminal Station), published by La Torraccia’s Cinefoto romanzo gigante in 1957 (figure 3.3). The magazine not only makes dubious remarks about a group of soldiers, but also uses them to create a risqué expansion of the narrative. At some point in the film, the main male protagonist Giovanni slaps his love interest Mary, a married American woman who would become his lover that very day, in an abandoned cart on a dead railway track. Frustrated by his ineffective attempts at convincing Mary to stay in Rome with him, rather than going back to her husband in Philadelphia, the Italian lover unexpectedly hits the woman in the main lobby. Nobody really pays attention to the couple besides Mary’s nephew, who is there to bring his aunt her suitcase and who acts as a sort of surrogate husband throughout the movie.47 The group of coscripts that happens to be “in the background,” exactly like the parade of Curaissers in the previously mentioned letter, witnesses the dramatic event without showing any interest, in a typical Zavattini-De Sica style of everyday settings. In Cinefoto, instead, the soldiers engage with the characters by means of added dialogue and a caption. The latter states that the soldiers find the scene “interesting” and thus gather around Mary, after Giovanni has left, “commentando salacemente l’accaduto” (commenting on the fact salaciously). One of them says in a balloon: “Sweet brunette, your boyfriend is jealous, isn’t he? I would have happily given you a kiss, not a slap!” (figure 3.4).48

Figure 3.3

Cover of “Stazione Termini” (Terminal Station), Cinefoto romanzo gigante, no. 28 (1957).

The case of “Terminal Station” is relevant to exemplify two important points: (1) modifications to the film’s plot and dialogue do not take into consideration the screenwriter’s and the director’s intent but rather an ideal reader modeled on current successful products; and (2) cineromances are not under the same level of government control as cinema. The chauvinist attitude paraded by the soldiers could either please or antagonize the audience (especially women), but with certainty fits the discourse of gender that is pervasive in popular Italian comedies of the period. Given that the American actor Montgomery Clift played Giovanni, the clash between the machismo of the soldiers and the ineptitude of the male character could also be interpreted in the name of national pride. This aspect is of particular interest considering that Terminal Station is at the center of a battle between the two co-producers, De Sica (who is also the director) and the American David O. Selznick, precisely in reference to the film’s possible commercial success or failure. It is known that Selznick heavily modified De Sica’s version of the film on the basis of poor reviews from viewers at preview screenings in California; in fact, Terminal Station was released in a much shorter version in the United States (where Selznick held all rights and with a different title, Indiscretion of an American Wife.49 The crass rewriting of the previously mentioned scene is similar to Selznick’s intervention in trimming the film with a certain target audience in mind, whose perspectives on masculinity differ from what is embodied by the main character in the film.

Being outside the lda had its disadvantages as much as its perks: discrepancies between the printed and audiovisual texts (in both versions) speak about the greater freedom granted to publishers who were at the margins of the cultural economy. The film industry and the national government were bound to each other in many postwar European countries, including Italy, and the lda enforced this connection. Under Fascism, Article 47 of the lda established that, in cases of dispute between producers and coauthors, the Ministry of Popular Culture (MinCulPop) was called in as an arbiter. After the fall of the regime, the Presidency of the Council of Ministers simply replaced the MinCulPop, thus continuing to allow political meddling in the judicial system.50 Since several laws also went unchanged in the transition from Fascism to Democracy, such continuity in the lda would not surprise if it did not clash with an opposite rush to change film legislation, in the name of artistic freedom. Immediately after the Liberation of Rome and as early as October 5, 1945, during Nazi occupation in Northern Italy, the Italian Parliament approved a new law on cinema with the immediate consequence of liberalizing the market.51 Nobody bothered to change the lda as well, and to actually give more power (of authorship) to the artists. Meanwhile, the flaunted freedom of expression was soon contained in the name of social order. In 1954, following a discussion at the Presidency of the Council of Ministers, in which the Christian Democratic government explicitly announced that funding would not be available to film productions that were deemed to have been under the influence of the Communist Party, a “McCarthy-style” campaign spread in the press, culminating with publication of a list of directors openly or allegedly Communist. While “the silent acceptance of governmental instructions” had always defined the attitude of producers vis-à-vis the Italian government, in this case the Associazione Nazionale Industrie Cinematografiche Audiovisive, Anica (the National Association of Film and Audiovisual Industry) went as far as to establish a commissione di autocensura (self-censorship committee).52 This committee had the goal to preemptively examine those films that might be subject to government censorship. De Sica was among the directors under scrutiny as openly Communist or sympathizers, together with Antonioni, Luchino Visconti, Carlo Lizzani, Alberto Lattuada, and Giuseppe De Santis, who were also among the subscribers to the “Manifesto” of the “Circolo romano del cinema” that, in 1955, publicly denounced the Italian government and its policies. According to the Manifesto, “the recent declarations and initiatives of the current Undersecretary of the Presidency of the Council of Ministers [Giulio Andreotti] are about to collapse the already dead freedom of expression under a gravestone.”53

Figure 3.4

Cover of “Stazione Termini” (Terminal Station), Cinefoto romanzo gigante, no. 28 (1957): 11.

This discussion of film legislation and censorship should not be taken as a digression. In the broader context of the power struggle between artists, the Italian government, and the industry, the uniqueness of cineromances consists of marginal yet deconstructive narratives in the established media system. Not by chance, Amedeo Giannini, whom I previously quoted in this chapter, is in favor of including photoromances under the protected works in the lda; at the same time, he is a member of Anica’s self-censorship committee, a promoter of more rigorous controls on films to “protect” viewers from their psychological effects, and in support of recognizing producers as film authors. A thorough comparative analysis of photoromances of controversial films in the history of Italian cinema may be fruitful to discover the extent to which the inclusion of cineromances under a revised lda that granted authorship to producers could ultimately aim at controlling how magazines popularized them to a mass audience. If recognized as “works of intellectual substance,” cineromances would also have to go through a rigorous policing that would protect but also inspect their content. Space here does not permit an extensive examination in these terms, but I would like to conclude this chapter by looking closely at one particular instance: a 1955 issue of Cineromanzo gigante based on Senso, directed by Luchino Visconti in 1954 and produced by Lux. For this film, Lux borrowed warfare materials from the Ministry of Defense that were necessary for the film’s realistic representation of the famous 1866 battle of Custoza, between the armies of the Austrian-Hungarian Empire and of the Kingdom of Sardinia.54 The same ministry asked Lux to cut some scenes and dialogues from the film that allegedly undermined the honor of the Italian army. The accusation was, once again, of vilipendio. The contested scenes are one that represents Austrian soldiers drunk and engaging with prostitutes in the streets of Verona (considered an attack on the moral integrity of the military) and one with dialogue between patriot Count Ussoni and Captain Meucci of the Kingdom of Sardinia that the Ministry of Defense alleged conveyed incomprehension and animosity between independent fighters and the official army. In addition, the Film Revision Committee requested some cuts of love scenes and related dialogues.55 Senso is, in fact, a story about the Italian Unification told through the love affair between Countess Livia Serpieri (married to a pro-Austrian aristocrat and cousin to the fervent Italian patriot Ussoni) and the Austrian Lieutenant Franz Mahler. Their relationship constitutes the backbone of a political narrative ridden with compromising moral and ideological content: Livia, played by Alida Valli, falls for Franz, played by Farley Granger, and for him she betrays both her husband and her country, using the money that she safeguarded for the cause of Italy’s independence to pay for Franz’s medical excuses that would cover up his desertion.

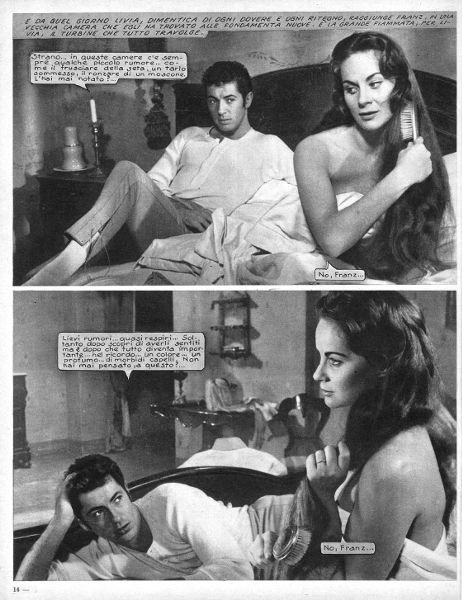

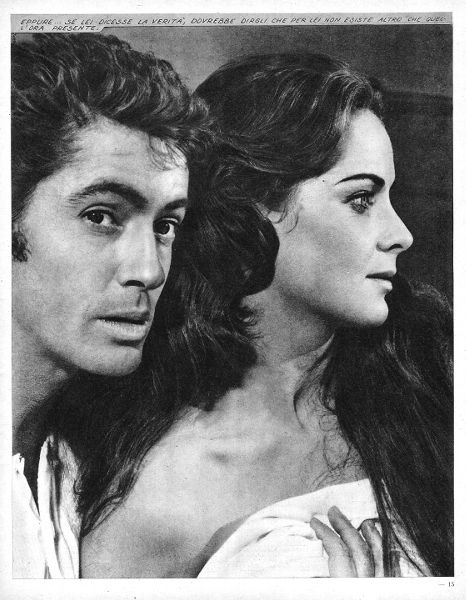

The film’s intricate plot and the main stars make Senso the perfect material for a cineromance. The vicissitudes of the film’s production provide an additional layer to the convergence of cinema and the press that is worth further attention. According to official documents, the Film Revision Committee asked Lux to cut a scene from “reel n. 4.” The document reads: “Livia is still in bed, after consummation of their love meeting [sic], Franz is near her. Livia combs her hair with a brush, also sitting in bed. (Eliminate the entire scene).”56 Instead, the cineromance includes not only this scene but also exactly the shot mentioned in the report. Valli is brushing her hair and sits on the bed, looking away from Granger, only covered by a sheet that reveals her naked shoulders; Granger looks at her while lying on the bed, with some distance between them (figure 3.5). The two-image grid is anticipated by a full-page picture of Granger and Valli, side by side in a close-up, with a neutral background that may or may not be the film set (figure 3.6). It is a publicity film still: the two actors are now close to each other, in a switched position, and Granger is looking right at the camera, breaking the illusion of film realism. Valli is instead taken in profile, which according to one biographer is also her best angle.57

Senso was meant to mark Valli’s great comeback, to regain the attention of her fans and to build positive publicity around her. Extremely popular during the Fascist period, the actress who was once “the most loved by Italians” had just come back from Hollywood, where she moved right after the end of the war amid accusations of being a spy for the Fascist regime. When Senso was released in 1953, she was again involved in a scandal that could ruin her image: her boyfriend Piero Piccioni’s alleged involvement in Wilma Montesi’s murder.58 Senso was a success at the box office, and the cineromance is a testament to Valli’s (and Granger’s) star power. Further, the character that Valli plays in the film is not in continuity with the wholesome image she held before the war. Rather, her role fits with those she interpreted under contract with Selznick in Hollywood productions such as The Paradine Case (dir. Alfred Hitchcock, 1947) and The Third Man (dir. Carol Reed, 1949): fatal beauty, a mix of corruption and redemption, extreme passion and irresistible desire. As expected, the Film Revision Committee requested changes to smooth over the explicit reference to the character’s moral ambiguities. In particular, the producer was asked to cut the line in which Franz alludes to the fact that Livia is worse than a prostitute, when she gives away the patriots’ money for her lover’s faked medical excuses.59 Of course, the line appears in the cineromance more or less in the same form, but with the additional argument that, in fact, she is not like a prostitute but rather like an old client of a gigolo: “What is the difference between the two of you [Livia and the prostitute]?,” Franz says. “I will tell you. You [the prostitute] are young and beautiful . . . and you [Livia] are old. Men pay for her, and you, for an hour of love, you had to pay me.”60 The caption condemns Livia’s behavior, and her decision to “forget any duty and any shame” when overwhelmed by her passion, indicating a conservative approach to the story.

Figure 3.5

“Senso” (Sensation), Cineromanzo gigante, no. 7 (1955): 14.

Figure 3.6

“Senso” (Sensation), Cineromanzo gigante, no. 7 (1955): 13.

And yet, the images of Valli’s (and Granger’s) attractiveness send a different message, despite their moral perversion, and much more questionable elements than marital unfaithfulness are kept in the story: in particular, the images that represent the Austrian soldiers in promiscuous activities with prostitutes, drunk and uninhibited, which the Ministry of Defense specifically censored. In the film, after the battle of Custoza, Livia arrives in Verona in a carriage to visit Franz. The guards let her in, but the Commander warns that “the city is not safe for a lady.” Right after the carriage enters surrounded by a crowd of men in uniform, including a stretcher on which a wounded body lies, a sharp cut introduces the scene inside Franz’s apartment (where he is staying with the prostitute). Instead, in the cineromance, the photo showing Livia in her carriage is followed by two contrasting images, representing the Austrian and the King of Sardinia’s soldiers, respectively. The first frame shows a street crowded with white uniforms. Its caption explains that an excited mob of drunken soldiers and prostitutes is taking over the city, laughing, singing, and making love, “while the defeat sends back hundreds of broken and bloody men.” The latter sentence is the caption on top of the second image, representing a caravan of wounded combatants, including both patriots and the King of Sardinia’s army.

The cineromance notably does not in any way support the critical vision of the Unification claimed by Visconti in his own reading of the film; rather, it modifies its content against the moral policing of the Film Revision Committee and in favor of a more enticing reader’s experience. A comparison between the representation of the only political event included in the cineromance, the battle of Custoza, to that in the film clearly shows how the former maintained a glorifying image of Italian patriots, albeit in its own popularizing fashion. In the film, Custoza is a chaotic event of extreme violence seen through the eyes of Count Ussoni, who wanders helplessly and wounded across the battlefield, walking over dead bodies and trying to find shelter behind dissolved trenches. The sequence begins with Ussoni as he passes by the army of the Kingdom of Sardinia that is slowly retreating (“it’s an order!” some soldier cries in the background). It ends with him looking at a small group of combatants who are firing the cannons. One of them announces that they will continue to fight despite the order, however, laughing coarsely together with his mates, he appears to have lost his mind rather than gained courage for an impossible mission. Ussoni observes them silently, and eventually disappears from the screen (and he will also no longer be seen in the film). In the cineromance, in contrast, the two pages representing the battle not only show Ussoni acting heroically (until his own death), but also joining forces with a group of Italian soldiers who are fiercely resisting the enemy, rather than frantically shooting at nothing as in the film. For those readers who may not have been aware of the historical facts, the battle retold on the pages of Cineromanzo gigante appeared more like a Western movie: “Un pugno di uomini deciso a resistere” (A bunch of men resolved to resist), states a caption over a frame enlargement showing Ussoni in the front, and a man on a horse in the background. Lanterna Magica’s version of Custoza celebrates the heroism of Italian soldiers, and if the Ministry of Defense had known, it probably would have approved. Its rendition is not really celebratory of the Nation, however, but rather, is appropriately geared to engage a cinema audience, at a time when a character that resembled John Wayne was more palatable than a trite eulogy of the fallen soldier.

The same could be said for what seems the most shocking discrepancy: the final sequence. Riccardo Gualino of Lux asked Visconti to reshoot the scene, at the behest of the Ministry of Defense, to include the execution of Franz by the hands of an Austrian fire squad as the closing image of the film. In an interview published in Cahiers du Cinéma, Visconti argued that Senso should have ended differently, with a sequence in which Livia walked (again) by a group of drunken soldiers.61 The last shot was supposed to be that of a young draftee, totally inebriated, who cried while shouting sarcastically “Viva l’Austria!” (Long live Austria!) Similar to the battle of Custoza, this instance should have represented a dark vision of war, emptied of heroic gestures and afflicted by the lack of meaning. According to Visconti, the negative that he shot was burnt and no positives of this sequence could be found. The final pages of the cineromance challenge Visconti’s assumption. After the execution of Franz, ten additional photographs (one page and a half) show Livia wandering in an empty street of Verona, eventually passing through a small square where, according to the caption, women and soldiers spend the night together. The first four photographs are taken from a previous sequence, after Livia leaves Franz’s apartment to visit the headquarters where she will denounce him to his superiors. The six-photo grid of the last page, however, does not appear anywhere in the film (figure 3.7). In these images, Livia is seen encountering Austrian soldiers, while the caption states that “nel suo cervello, la follia è esplosa” (in her head, madness has exploded). It is impossible to say with certainty whether these images are in fact taken from the negative that Visconti originally shot for the final sequence. Their focus is different from Visconti’s planned critique of war as violent and senseless; the attention is on the female character and her tale of corruption and redemption. At the same time, the shadow that the scene casts on the Austrian army is closer to Visconti’s intentions and definitively against the directives of the Ministry of Defense. Lost in her sins and desperation, according to the captions, Livia is soon to be violently taken by an “aroused soldier” (“voglioso”) against her will. “She does not even see those outstretched hands and sneering faces,” the caption says, “as the circle of soldiers narrows around her.”62

Figure 3.7

“Senso” (Sensation), Cineromanzo gigante, no. 7 (1955): 59.

At the end of Senso, the image of justice served to a traitor serves to make a moral statement. The film’s “archontic” retelling in Cineromanzo gigante is much darker in its reading of the same story from the point of view of the female character, whose symbolic death happens by the violent hands of the men in white uniforms. This ending in fact reconnects the cineromance to the literary text, “Senso” (1883), a short story by Camillo Boito, on which the film is loosely based. Both the cineromance and the story concentrate on Livia’s vicissitudes, told from her own perspective, while the film (despite the use of the voice-over commentary by Valli) ultimately gives more prominence to the historical context and thus to an allegorical reading of the romance at its center. Told in a long flashback by means of Livia’s diary, recounting her past and sin, Boito’s text ends similarly to the cineromance (and differently from the film) with a scene that explains what happened to the woman after the death of Remigio (aka Franz): she is now the lover of a man who left his fiancée the day before their wedding, and whom she embraces while still thinking about her past companion. This is perhaps what awaits Livia beyond the last photo in the cineromance; most relevantly, both in Boito’s story and in the film’s “photoromanced version,” Livia’s moral degradation is what seals the whole narrative.

Lucia Cardone has argued that, when turned into cineromances, films “absorb the dark tones of the feuilleton, because they inherit the same [female] audience, passionate and demanding.”63 While I do not think that this is necessarily true for every cineromance, it is at least partially the case in “Senso,” which rewrites Visconti’s historical drama by drawing from Boito’s nineteenth-century short story. At the same time, considering the scenes that I previously analyzed, including that of the Battle of Custoza, the “dark tones” appear to be mixed with the bright ones of heroic gestures typical of other, popular genres. In the end, the hybrid text of the cineromance, rich in intertextual discrepancies and continuities with both the literary story and the film, is a growing “textual archive” that, in its expansions across media platforms and its exclusion from the legal system, challenges established notions of copyrights and intellectual property.