5 Birth Control in Comics

In 1976, on the pages of Corriere della Sera, Umberto Eco praised an experiment that took place in a middle school of the popular Roman neighborhood “Torre Spaccata:” a group of students had created a photoromance about one of their favorite celebrities, swimmer Novella Calligaris. “Knowing to read these new myths and discovering the teaching hidden beneath forms of entertainment is a new approach to schooling that prepares one for life,” claimed Eco.1 Written about ten years after the publication of his seminal essay on mass culture Apocalittici e integrati (Apocalypse Postponed, 1964), Eco’s short contribution sustained a positive attitude toward mass media, arguing that the form itself could be used to criticize the ideas that were purportedly imposed on its users. Speaking of photoromances, Eco’s friendly words were at odds with the widespread contempt or condescension that most scholars and journalists usually employed at the time when they talked about these magazines. In a sharp and typical critique, Luigi Compagnone in the same Corriere had only two years earlier declared that, the photoromance “does not give people to read, only to look; thus it eludes language and accustoms them not to think.”2 Writing in a column titled Risponde Compagnone (Compagnone Responds), the well-known fiction writer and journalist received many letters from readers who were offended by his words, which he quoted in a follow-up article in the same column (a few weeks later). In a highly ironic tone, Compagnone replied by dismissing resentment and complaints, and insisted that “the reader of photoromances is a passive subject because he [sic] is deprived of language.”3

However, Eco was not alone in believing that the photoromance could contribute to people’s education. Initiatives like the one in Torre Spaccata were not unique in the seventies, especially in educational contexts such as schools and activist organizations, both in Italy and abroad.4 In 1972, for example, a group of Italian architects and designers named Gruppo Strum participated in the exhibition Italy: The New Domestic Landscape at the Museum of Modern Art in New York with three photoromances that, according to an officially released document, depicted “the present conditions of urban decay,” described “the methods which may be adopted to change the present situation,” and catalogued “all forms of urban utopias presently envisioned by designers.”5 The architects and designers used the area assigned to them as a space where the illustrated stories were distributed free of charge to visitors because, in their words, no “physical forms” were capable of communicating their thought. Between 1973 and 1976 in Ecuador, the Peace Corps also experimented with the use of “photonovels” (instead of films) to educate Ecuadorian peasants on “subjects as diverse as environmental sanitation, prenatal and postnatal nutrition, malaria control, and family planning.”6 According to a Peace Corps publication titled The Photonovel: A Tool for Development: “Filmstrips, posters, and flipcharts were abandoned, after trials, in favor of the photonovel, because of its ability to communicate a detailed message through words and vision, while entertaining at the same time.”7

Among the letters that Compagnone received against his tirade, the one written by Sergio Montesi advertised a “fotoromanzo anticoncezionale” (contraceptive photoromance).8 Montesi wrote on behalf of the Italian Association for Demographic Education (AIED), which sponsored the publication of three photoromances as part of a larger campaign to educate Italians on the benefits of birth control and the low risks of the contraceptive pill. Against the idea that romances could only be apolitical and escapist, the stories of relationships narrated in AIED photoromances aimed at spreading behavioral models that were deemed appropriate by its sponsor’s policy of public health. In doing so, AIED addressed not only the issue of unwanted pregnancies but also that of sexual rights for both men and women in a country still predominantly patriarchal, despite women’s increasing liberties in both the private and public spheres. The extremely low number of contraceptives users and the high number of illegal abortions made the AIED’s romantic stories a timely effort, supported by the extraordinary success of the photoromance itself among mass audiences.9

Published by the Institute for Demographic Research and Initiative (IRIDE), the AIED’s research arm, “Il segreto” (The Secret), “Noi giovani” (We the Youth), and “La trappola” (The Trap) used the technique of the foto-racconto-lampo (flash photo-story) a type of photoromance first invented by the Roman firm Lancio in the late 1960s.10 The AIED flash photo-story consisted of a brief narrative that delivered a clear message: contraceptives were the secret weapon for a happy sexual, romantic, and social life. As I will show in the following paragraphs, this message was embedded in stories that pushed the previous boundaries set by the Italian birth control movement with regard to sexual conduct. Following the tradition of American educational media, however, AIED’s rhetorical strategies were not as new and original as Montesi claimed; at the same time, they departed from this tradition by uniquely engaging with Italian celebrity culture.11 In this way, the 1970s AIED campaign not only was innovative in Europe in the use of photoromances for propaganda purposes, but also demonstrated a deep understanding of what made the medium so successful among the masses.

The Campaign: Crossing Boundaries

“Birth Control in Comics”: with this title, in 1974, the national newspaper La Stampa announced in the imminent publication by AIED of the three photoromances mentioned earlier—“The Secret,” “We the Youth,” and “The Trap”—to advertise and promote the use of contraceptives.12 Celebrities such as actress Paola Pitagora, TV celebrity Mario Valdemarin, and singer Gianni Morandi provided testimonials for the campaign. Morandi eventually did not take part in the project, with Ugo Pagliai replacing him in the leading male role of “We the Youth.” The three photoromances initially were distributed for free, 60,000 copies in three pilot cities: Novara, Arezzo, and Salerno.13 In the following years, other cities were targeted as well as smaller groups for more specific survey purposes. For example, the photoromances were given to a focus group of two hundred male factory workers to test their attitudes toward birth control via an anonymous survey.14 The back cover of each issue featured the AIED as sponsor, followed by a list of different birth control methods and products, and addresses of local “consultori” (i.e., free clinics where women could receive medical attention, psychological support, and access to birth control methods). Ugo Fornari is indicated as author of both the story and the script of “The Trap” and “We the Youth” while Marco De Luigi is indicated as the same for “The Secret”; both names, however, were pseudonyms of Luigi De Marchi (figure 5.1).

The 1975 AIED contraception campaign was announced in the press as both the evidence of progress in the sexual education of Italian citizens and as the ultimate success of “the tireless” De Marchi, president of the AIED and sexual rights activist, who had just a few years earlier appeared in Italian newspapers for the groundbreaking court ruling that legalized the making and distribution of birth control propaganda in Italy.15 In the mid-seventies, Italy was still behind in comparison with other nations, such as the United Kingdom or the Netherlands, with regard to sexual rights legislation as well as sexual education. According to Gianfranco Porta, in a recent history of the AIED titled Amore e libertà, “founding norms of fascist natalism” that considered neo-Malthusian theories of population planning “a crime against the integrity and health of race” were still in place in the new Republic.16 In fact, Fascist laws against the use of contraceptives were not dismantled but converted into prescriptive rules that regulated sexual behaviors according to Catholic moral values.17 Until 1971, Italian law prohibited fabricating, importing, buying, distributing, and possessing writings, drawings, and images to propagate birth control methods. Article 553 stated that “anyone who publicly incites use of birth control methods and makes use of propaganda in their favor can be punished to up to one year in prison and to a fine up to four hundred thousand lira.”18 In 1975, contraceptives were still officially accepted only for married couples: the official commentator of a newsreel portraying a parliamentary discussion on contraception stated that “it is necessary to inform pervasively, starting from the idea that planned parenthood has nothing to do with free love.”19 Finally, while in the 1960s and 1970s new laws were passed in many European countries to introduce sexual education in school, in Italy the topic was never seriously debated in the Parliament (see for example, the law proposal by Communist deputies Giorgio Bini, Adriana Seroni, and others in 1975).20

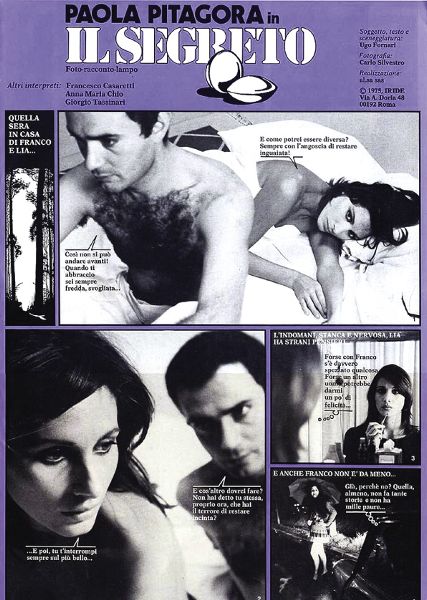

Figure 5.1

Cover of “Il segreto” (The Secret, 1975).

According to Dagmar Herzog, “scholars ten[d] to oscillate between presuming either that the growth of a culture of consumerism and the medical-technological invention of the birth control pill in the early 1960s sparked the sexual revolution or that this revolution was the logical result of courageous social movement activism on behalf of sexual liberties, legalization of abortion, and gay and lesbian rights.”21 De Marchi’s photoromances, and their reception in the press, convey the idea that the use of contraceptives was both a trigger and an effect of the sexual revolution in Italy.22 In this context, the AIED’s photoromances constituted the first nationwide campaign for the birth control pill that detached the sexual act from both procreation and marriage. In anticipation of their publication, De Marchi declared to the press, in open confrontation with both the Vatican and the current political establishment, that Italian doctors who were not in favor of contraceptives contributed to a widespread demonization of sexuality in Italian society. Furthermore, birth control was strictly related to modifications in the ways in which sex was perceived, represented, and repressed. He reportedly said, “Historically, sexuality has been based on a neurotic balance—a sin that leads to a guilty conscience one must overcome through penance. Until now, such penance has been presented under scientific terms.”23

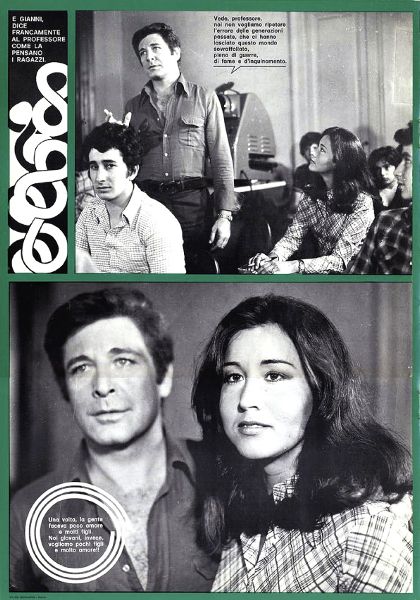

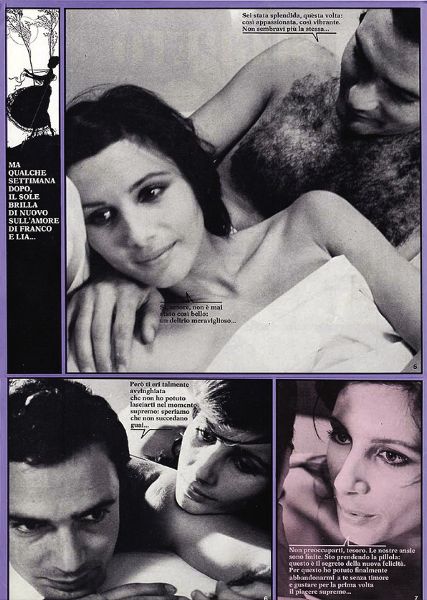

De Marchi’s statements were clearly influenced by Wilhelm Reich’s theories (of which he was a translator), which he programmatically embedded in his book Sesso e civiltà (1960). There, De Marchi basically asserted that sexual taboos prevented the healthy functioning of societies. In many ways, dialogues and captions in “We the Youth” and “The Secret” reflect De Marchi’s perspective and present the pill as the tool to liberate sexuality, while also communicating that the commercialization of contraceptives depended on the spread of radical thinking about sexual conduct. In “We the Youth,” the youth talk about the pill as the means to free love but also as “a form of revolution against the fathers’ civilization.”24 In the closing photograph of “We the Youth,” the young couple of the story is caught in a close-up as they look obliquely at the future, sealed by a caption that says, “Once upon a time, people made little love and many children. We that are young, we want less children and more love!!” (figure 5.2).25 In “The Secret,” the female protagonist Lia explicitly argues for the use of the pill in order to liberate sexual intercourse from the burden of reproduction. A culture of pleasure substitutes for an imperative of fertility as a sign of virility, for men, and of faithfulness, for women. In the story, Lia contemplates being unfaithful because she is not satisfied with her partner, Franco, but is plagued by “l’angoscia di restare inguaiata” (the anxiety of getting in trouble).26 Franco, on the other hand, wonders whether it would be better to go with a prostitute since “at least she doesn’t make a fuss and doesn’t have any fear.”27 Eventually “the secret of [their] new happiness” is the pill, thanks to which Lia can finally let herself go and, in her words, “taste ultimate bliss for the first time” (figure 5.3).28

Figure 5.2

Last page of “Noi giovani” (We the Youth), starring Ugo Pagliai and Paola Gassman (1975).

Figure 5.3

“Il segreto” (The Secret, 1975), 7.

In a country where, in 1978, women’s pleasure was still “marginal and accessory” and “accepted only as [a] component of the procreational purpose,” to quote Fabris and Davis’s survey on the sexual behaviors of Italians, “The Secret” was truly groundbreaking.29 At the same time, “The Secret” fit perfectly in the historical context of 1970s Italy where, while conservative positions were still predominant at the level of legislation and government, mass culture was increasingly more risqué in representations of sexuality and the press suffered from a “polling fever”30 that—like in other European countries before—resulted in sex being “talked to death.”31 In addition to academic research, surveys were published in popular Italian news magazines such as Panorama (1977) and L’Espresso (1978) to discuss the knowledge and habits of Italians in matters of sexuality.32 As Lucia Purisol writes in Corriere della Sera, “Women’s weeklies tried to fill the gap in sexual education via ‘R-Rated’ surveys, reports and inserts.”33 Other articles published in Corriere della Sera and La Stampa celebrated the AIED for its contribution to the sexual education of Italian citizens. Such publicity for the AIED aligned with other journalistic reports on sexuality insofar as it redefined the public discourse by “a marked medicalization and scientification.”34 An example can be found in La Stampa, which in 1974 published in three subsequent articles the results of a sexual education survey conducted at the Istituto Superiore Einaudi.35 On the same page of the second report, in which students freely discuss their sexuality, another article advertises a press conference titled “Fate l’amore, non i figli” (Make Love Not Children) during which “a new contraceptive method” was presented: the photoromances.36 While the article’s intention to turn this cultural product into a scientific method in itself may be farfetched, it is fair to say that medicine and scientific innovation play a significant role in the stories. In addition, each story ends with an advertisement of contraceptives including brand products such as Rendell, Lorofin, and Taro Cap. While the “inserto informativo” (informative insert) was clearly meant to provide scientific knowledge with regard to these products, their branding added commercial value to a publication whose goal was supposed to be exclusively social (and not for profit).

Despite the fact that public information campaigns promoting birth control were illegal, other contraceptive methods had already been advertised in magazines in the late 1960s. In Bolero Film, a commercial for CDI, “il nuovissimo Sistema Combinato” (the very new Combined System) promoted a “natural method” of contraception that was supported by the Catholic Church and recommended by doctors (according to the ad).37 There are no documents that prove the AIED was in any way behind this initiative; however, the slogan for the product was strikingly similar to Vittoria Olivetti Berla’s motto in the essay she wrote in defense of family planning in 1954. “CHILDREN, YES (but at the right moment),” said the CDI commercial; “all and only wanted children, at the right time,” wrote Berla, who was at the time vice president of the AIED.38 What is relevant in the similarities between Bolero Film’s ad and Berla’s statement (as well as Planned Parenthood’s, for that matter) is the focus on the institution of marriage as the appropriate space to speak of “responsible procreation.”39 Indeed, in its founding principle, the AIED did not aim at freeing society from sexual taboos, as De Marchi argued in his books and interviews; moreover, the organization did not at all consider contraceptives to support the sexual revolution. Founded in 1953 by a mixed group of bourgeois intellectuals, industrialists (such as Adriano Olivetti), radicals, and Socialists (including De Marchi), the AIED promoted birth control as “an economic intervention”—to solve the world’s overpopulation problem—and “the means to allow an individual to be free and aware of his [sic] own life and of his offspring.”40 In this sense, the AIED resumed the activities of Socialists and radicals who, since the early twentieth century, considered birth control in response to the effects of industrialization, and embraced the Neo-Malthusian ideas with the goal of fighting poverty as well as with the purpose of regenerating Italian society.41

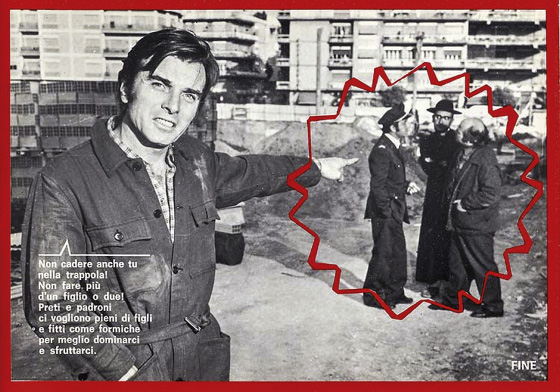

In both “We the Youth” and “The Trap,” the radicalization of these principles conveyed De Marchi’s unique perspective rather than that of the Italian birth control movement as a whole. In “Noi giovani,” the young activists aim to solve worldwide issues of overpopulation, hunger, war, and environmental damages, like the birth control movement did; at the same time, their leader Gianni announces that free love is the tool to achieve such a goal (as claimed by De Marchi in his conversation with Guido Credazzi).42 In “The Trap,” the main character Marco is an unskilled worker employed by a greedy contractor who struggles to make ends meet when his fourth son is born. At the end of the story, Marco warns a young fellow worker not to have more than two children (as De Marchi did in the previously noted interview) and explains that “priests and bosses” want workers “full of children and crammed like ants to better dominate and exploit [them]” (figure 5.4).43

Figure 5.4

Last page of “La trappola” (The Trap, 1975).

In sum, AIED photoromances draw from both mass culture and the tradition of the Italian birth control movement while pushing their own political and moral agenda. In “We the Youth” and “The Trap,” anti-capitalist and anti-clerical ideas infuse the middle-class concerns for the world’s overpopulation and the poor, while free love is claimed to be effective in solving the issue of the “population bomb” and its deleterious effects on humans and the environment. Furthermore, while photoromances on the market were mostly conservative in their visual representations of sexuality, “The Secret” was far more explicit in both words and images. According to a Lancio spokesperson, “There was never a nude scene, never pornography. In bed, she wears a high-necked shirt with long sleeves and he wears a sailor shirt.”44 The scene in the bedroom in “The Secret” shows precisely the “nudo” so much feared by Lancio. Several pictures represent in medium shots and close-ups a couple lying in bed, undressed albeit under the covers; the woman reveals her bare shoulders, the man sits upright with his chest naked. The couple not only shows that they had been intimate, but they both talk about sexual intercourse and about the pleasure that they may (or may not) have gained from the act. Furthermore, neither Lia nor Franco refers to each other as husband and wife. Some critics take for granted that the couple represented in “Il segreto” is married; however, this is not at all made explicit in the narrative. Such detail, in addition to the characters’ conversation, shapes the message in support of contraception delivered by “The Secret” with the purpose of liberating sexuality from both the act of procreation and from the institution of marriage.

These claims were not only radical vis-à-vis the AIED’s founding principles, but also with regard to the position held by the association in current contributions to illustrated magazines. In 1974, one year before the publication of “The Secret,” two reports on women’s “intimate lives” sponsored by the AIED were published in Grand Hotel.45 Each report featured an advertisement for the AIED that stated: “A center where they teach you how to make love without the woman getting pregnant.”46 The first report discussed the topic of virginity “with candor and without prejudices” while the second explained “how to avoid unwanted pregnancies.”47 In both issues, Grand Hotel sent a clear message to its female readership: sexual intercourse was both natural and acceptable—however, “in una cornice di sentimento” (in a love setting) that could only be legitimated by marriage. As written in the second report, “The main goal of marriage is no longer to have children, but the couple’s happiness and harmony. . . . However, we must learn how to have children only when both desire them. It is necessary that everyone knows how to do that.”48

Clarence J. Gamble and De Marchi’s Rise to Celebrity

“Every child a wanted child” not only is the message conveyed in illustrated magazines and in Berla’s essay, but also the title of Doctor Clarence J. Gamble’s biography, which Doon Williams and Greer Williams wrote in 1978 to celebrate the life of this American millionaire who devoted his fortune to the cause of birth control in the world, particularly in developing countries. Gamble was initially associated with Margaret Sanger and Robert Latou Dickinson, and the American birth control movement more generally; “every child a wanted child” was also the slogan of Planned Parenthood, previously known as the American Birth Control League and founded by Sanger. In 1957, Gamble created his own organization, Pathfinder Fund, to continue promoting education and funding distribution of birth control supplies, especially outside the United States (in 1991, it was renamed Pathfinder International). Both Gamble and Sanger considered eugenics an acceptable method to control overpopulation. Retrospectively, their position is controversial; however, at the time, forced sterilization was part of the broader effort to fight the so-called “population bomb.” Similarly, the AIED’s intention was to “reduce illegitimate births, infanticides, voluntary abortion, teen mother suicides, genetically retarded offspring”).49

In the mid-fifties, Berla was Gamble’s initial contact in Italy, but soon he became close to De Marchi and his wife, Maria Luisa Zardini De Marchi (from now on, Zardini).50 The relationship between Gamble and the De Marchis has not been investigated much; however, I maintain that it considerably affected the history of AIED and its campaigning efforts.51 As an official publication of Pathfinder International states, “support from Clarence Gamble and Pathfinder enabled AIED to flourish and the De Marchis turned their mission to legalize birth control into their permanent employment.”52 Beyond the celebratory goal of this booklet, my goal is to understand the influence of such a partnership on the politics of the AIED in general, and on the making of the 1975 campaign more specifically.

De Marchi had been at odds with Berla since the publication of Sesso e civiltà. In Berla’s view, De Marchi advocated free love and therefore was a menace to the Italian birth control movement.53 De Marchi, on the other hand, claimed that his “personal” opinions should not matter to the AIED, since he deemed his engagement as the secretary of the Roman branch separate from his work as social psychologist and sexual rights activist. Berla never made peace with De Marchi, left the AIED in 1963, and with her departure the association lost the support of the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF).54 This seemingly marginal incident is relevant to my discussion because it sheds light on how De Marchi’s rise to a prominent role in the AIED (he became its president in 1961), and thus his ability to single-handedly manage the 1974–1975 campaign, happened at the expense of its more moderate faction, represented by Berla. Furthermore, Berla’s departure from the AIED, together with the IPPF sponsorship, corresponded to the increasing involvement of Gamble and his organization, the Pathfinder Fund, in support of the De Marchis’ personal and political battle for birth control and sexual rights.

Gamble and Pathfinder Fund financially supported De Marchi consistently so that, despite the opposition he faced inside the AIED, he could rise to national and international attention for the historic ruling of the Italian Supreme Court in favor of birth control. Indeed, Zardini and De Marchi distinguished themselves from other activists at the AIED not only because of their radical ideas but also by openly and aggressively defying the Italian law. As Anna Treves explains, De Marchi (together with Guido Tassinari) was at the head of the AIED’s “radical wing,” employing strategies of civil disobedience in order to repeal Article 553 and liberalize the use of contraceptives. In her words, “they wanted to be charged, moreover, they demanded it; and then, systematically, they rejected the judiciary’s tendency to dismiss charges.”55 Treves does not acknowledge, however, that this “radical wing” could not have engaged in unruly behavior without Gamble’s help. Pathfinder Fund regularly paid De Marchi a consultation fee, which allowed him to concentrate on his legal battle almost full time. In addition, he provided free vaginal diaphragms and contraceptive jelly (from the United States) to the free clinic that De Marchi and Zardini opened in Rome in 1956, and which resulted in De Marchi being charged for violation of Article 553, but did not lead to trial. In 1969, De Marchi was again charged in violation of the same article for opening a free birth clinic in Rome. By that time, Gamble had passed away, but Pathfinder Fund continued to help the AIED with funding, and while the American organization did not provide financial support for the court case, it publicly supported the couple throughout it. Eventually, when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of De Marchi in 1971, the AIED was finally free to promote birth control and to open more clinics (the so-called consultori); a few years later, in 1974, Pathfinder Fund financed the first major campaign that included the publication of photoromances.56

Beyond financial support, Gamble also invested in both De Marchi and Zardini to foster his own agenda. In this context, Zardini was especially important in promoting Gamble’s project of spreading the use of contraceptives among the poor. Gamble visited the couple for the first time in 1958, right after he split from the IPPF, when he created the Pathfinder Fund. The IPPF criticized Gamble’s work ethic, specifically, his trial in Punjab, India, where he pushed a “simple” birth control method (the so-called salt-and-sponge method), which was proven to be very uncomfortable for women and not very effective. Gamble and his fieldworkers were criticized for their colonial approach toward their clients (who received contraceptives without much control over their own well-being). In addition, the IPPF did not approve of Gamble selecting nonmedical personnel (particularly women over age fifty) as fieldworkers. During his first visit, Gamble came up with the idea of a contraceptive field trial to be conducted in extremely poor Roman neighborhoods.57 Soon after, Zardini was appointed to lead the trial and began door-to-door visits to families in the tenements and shacks to deliver vaginal suppositories, which were provided free of charge by a manufacturer in England. For a while, Zardini also promoted the salt-and-sponge method, at the behest of Gamble; however, the method was not successful among Italian women and was quickly abandoned.58 Zardini’s endeavor, which she undertook with only one other female colleague, was impressive: working against current laws that prohibited the distribution of contraceptives and under the strong opposition of the Vatican (whose emissaries spied on her movements), she had 588 clients and made about forty thousand visits.59 Zardini reported on these visits in the book Inumane Vite (1969), and yet we know very little about her attitudes toward the women she encountered. An episode in the documentary I misteri di Roma (Rome’s Mysteries, 1966), titled “Maternità” (Maternity), uniquely represents Zardini at work as she talks to a woman who had been receiving her assistance for a few years.60 In a scene, Zardini hastily engages with the woman, asking how many packages she would need during the summer (saying she might be gone for the entire month of July); then, she scolds her client for not taking good care of the products that are “so expensive” and makes her promise that she will be more careful in the future. The woman looks both grateful and intimidated, and when she speaks to the cameraman (who is also present in the scene), the client fiercely declares that she does not want any more children and does not care whether the Catholic Church disapproves of her actions, as the interviewer suggests is the case.

Clearly, this scene does not reveal the “truth” regarding Zardini’s role as an educator, especially given that the film was intentionally shot in a verité style, questioning all claims of the ontological truth of cinema. At the same time, by connecting these images to the commentaries on Gamble’s colonial approach in his trials, I aim to broaden the picture of their relationship and better understand its impact on the Italian birth control movement. In particular, I think that this background information is useful to explain the strong criticism expressed by feminist groups against the AIED in the mid-1970s, that is, right around the time of the campaign.61 For example, the Associazione per l’Educazione Democratica (Association for Democratic Education, AED) argued that the AIED neglected women’s rights to control their own health and reproductive power. In the preface to Manuale di contraccezione (Manual of Contraception, 1975), AED’s National Secretary Nerina Negrello claims that the process of “population planning” was incentivized in Italy thanks to American funding agencies that financially supported associations that focused on decreasing pregnancy numbers rather than promoting free choice. In her words: “Power does not care about individual self-management with regard to contraception. To acquire freedom means to frustrate the monopoly of the fertility tap.”62 Negrello does not refer to Gamble or Pathfinder, but the manual nominally attacks the AIED for experimenting with contraceptive methods on Italian women while being aware that they were not effective.63

Negrello’s commentary and De Marchi and Zardini’s association with Gamble, a conservative Republican, problematize readings of the AIED’s photoromances that claim their evident support of the feminist cause—for example, that of Elisabetta Remondi in Genesis, the journal of the Italian Association of Women Historians. At the very least, Negrello addressed a gap in the discourse of sexuality and reproduction conveyed via their narratives: on the one hand, plot and characters support women’s emancipation by claiming their right to sexual pleasure; on the other hand, they do not address what was also in women’s rights, that is, their freedom to decide whether or not to be mothers. Pathfinder Fund’s influence on the photoromances, beyond its financial support, can thus be approached from the point of view of the ways in which the American funding agency may have limited the political message that De Marchi promoted in his own claims to the press. According to Remondi, AIED photoromances radically rejected patriarchy by promoting birth control: “The goal was to have a couple in which individuals were connected to each other, neither according to a model of women’s subjugation to men typical of patriarchal societies, nor by the fear of loneliness that characterized so many women’s lives, but rather on the basis of mutual growth and knowledge.”64 In fact, as I previously mentioned, these narratives are certainly radical in the way they address sexuality but do, however, maintain male partners in a position of leadership, and female characters as subordinate companions. Indeed, in “The Secret,” Lia does make the revolutionary gesture (and openly tells her partner) to fully enjoy sex; at the same time, she concludes that her satisfaction has the ultimate effect of gratifying her man. In her words: “Now other men don’t interest me anymore because you give me everything.”65

“The Trap,” “We the Youth,” and “The Secret” did not undermine the system in which men ruled over women; instead, they motivated men to allow their female partners to take the pill. In Dagmar’s words, De Marchi “developed a brilliant strategy for promoting contraceptive use which also implicitly revealed men’s discomfort.”66 As both “The Trap,” with its male leading character, and the focus group of male workers in a factory further testify, if women were considered by default the target audience of the campaign—“Accetteranno questa lezione le lettrici dei fumetti?” (Will women readers of photoromances accept the lesson?) states a journalist most explicitly—a careful reading of the project reveals that men were equally addressed as an interested party.67 Furthermore, in order to be persuasive, women’s sexual freedom had to be presented in a way that was not threatening to traditional notions of masculinity. As reported by Aida Ribero in La Stampa, Italian women hid from their husbands that they were using the pill. “Lui non vuole” (he does not want me to), Ribero states in La Stampa, quoting unnamed sources; “if he knows he gets mad” and “he keeps my pills locked in a drawer.”68 Similarly, Zardini reported that husbands of women in her trial were often suspicious, made her visits difficult, and many “felt that contraceptives were an affront to their manhood. They worried that without the fear of pregnancy, their wives would ‘be free to go with someone else.’”69

Rather than trying to convince women and their male companions that contraception was needed to prevent a global crisis, or to rid them of guilt (for having more children than they could possibly care for), these photo-stories were meant to engage them on the basis of positive incentives such as sexual satisfaction, happiness, and freedom.70 In other words, instead of basing the information campaign for contraceptives on the repressive logic of top-down instruction, the photoromance exploited the popularity of the media and the entertaining function of photography and narrative to productively involve readers in their education, and thus promote self-policing practices. This kind of “motivational propaganda,” nevertheless, was not De Marchi’s “brilliant idea,” as Remondi and Dagmar suggest. His technique followed a model already experimented with by American organizations and corporations, since the 1940s, to educate and train workers, soldiers, and the youth.71 More relevantly, as I previously mentioned, the Peace Corps experimented with the use of photoromances to educate Ecuadorian peasants. The project was funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), the same agency that in 1973 had provided Pathfinder Fund with a worldwide family planning grant of $11 million over three years, part of which was used to support the AIED’s campaign. Could it have been just serendipitous that De Marchi had exactly the same idea in 1974, when trying to figure out a more effective way to spread the use of contraceptives in a country where only 5 percent of the population made use of them?72 Was the AIED’s initiative a unique initiative, or, rather, was the Italian organization inspired by the work of the Peace Corps in Latin America (or instructed by Pathfinder)?

The Italian and Ecuadorian projects had many aspects in common. In both countries, photoromances were widely popular, a cheap form of entertainment, and particularly liked by sectors of the population of low income and little education. What was really new in De Marchi’s experiment was the engagement with the media system and with the world of celebrities. The imminent publication of the AIED photoromances was advertised in major newspapers. “Paola Pitagora teaches how to use the pill through comics,” titled a full-page report on the initiative in Corriere della Sera, which included interviews with Pitagora, Gianni Morandi, and Mario Valdemarin.73 Pitagora revealed that she herself took the pill, while Morandi expressed his opinion in favor of contraceptives to fight illegal abortion. “Volunteer and unpaid,” these celebrities were said to be taking part of the initiative for “social reasons.”74 Morandi stated, “I promised to collaborate in AIED’s initiative also because I think that workers will be able to better fight their cause when they are not worried about a large family.”75 Even though Morandi did not act in “Noi giovani,” the main character (also named Gianni) appears to be modeled on his star persona in the Italian musicals of the time. Gianni not only urges Maria (the female protagonist) to go to the lecture, but he also voices the youths’ concerns toward their parents, and their wish to not “make the same mistakes” by postponing parenthood and enjoying free love. In his behavior, Gianni may recall the rebellious and charismatic protagonist of In ginocchio da te (On My Knees For You, 1964), interpreted by Morandi, and even though “Gianni” is not Morandi, such cross-references seem intentional to make the character (i.e., the user of contraceptives) a more likeable and positive model to young readers.76

Eventually, Gianni was portrayed instead by Ugo Pagliai. The casting of Pagliai is again very significant, since he was in a romantic relationship with Paola Gassman, who played Maria. Pagliai and Gassman had been together since 1967 and often in the spotlight for their steady and passionate relationship.77 Considering that they were both in their thirties, the couple did not seem appropriate to interpret the role of college students. However, their private life together may have been more relevant here in order to bridge the fiction of the photoromance and the reality of readers. Their modern relationship was not institutionalized (they were not legally married) but lasted a long time; they had a child together, and lived as a family with Gassman’s daughter from a previous relationship as well.78 Pagliai publicly declared that he did not know whether he would marry Gassman but that he valued his family’s happiness more than “la carta bollata” (a piece of paper).

Morandi and Pitagora were also known for their sentimental affairs, even though in a very different way. Pitagora’s celebrity persona was built on being both sexually attractive and a feminist. As explained in an interview with Corriere della Sera in 1975, titled “Alle femministe piacciono molto gli uomini” (Feminists Like Men Very Much), Pitagora was known for being frivolous and exhibitionist, on the one hand, and politically engaged, on the other. In her responses, Pitagora argues that from her perspective, taking part in the AIED campaign was “something civil” however negatively viewed by many.79 She calls herself a feminist, and explains that her feminism is a new kind of womanhood: “freer and more informed.”80 In this sense, Pitagora’s role in “Il segreto” played on her existing star persona that, in turn, may have influenced a feminist reading of the photoromances. Her initial pairing with Morandi in the announcement of the campaign could have further influenced similar expectations. In 1973, Morandi allegedly had an affair with Pitagora, when the two of them starred in the musical Jacopone.81 On the cover of Grand Hotel from July 1974, the three of them are portrayed together; the title reads: “There is still the shadow of Pitagora . . . between Morandi and Laura.”82 The news of the affair had increased both Pitagora’s and Jacopone’s popularity (the show had failed at the box office), but had also made Pitagora and Morandi’s joint participation in the AIED project more intriguing from the point of view of their fans.

In this light, the use of celebrities mirrors the project’s mixed position with regard to gender roles and sexuality. On the one hand, the AIED’s photoromances promoted traditional ideas of true love and fidelity; on the other, they openly supported modern types of relationships (i.e., not institutionalized). Furthermore, both female and male stars appear to have been chosen for their looks, thus paying attention to the affective rather than the intellectual engagement of both male and female readers. Pagliai was certainly a favorite “divo” among women, as stated in 1971 in “Il mondo della donna” (A Woman’s World), a special section in Corriere della Sera. An acclaimed theater performer, but popular for his roles on television (he played among others Casanova, “the irresistible Latin lover”), Pagliai allegedly received even more letters from fans than Mastroianni ever had, and was one of the celebrities most photographed by paparazzi.83 Mario Valdemarin, who plays the protagonist in “The Trap,” was hailed “il Montgomery Clift italiano” (the Italian Montgomery Clift) by his young female fans who followed him on the show Lascia o raddoppia, where he was a contestant in 1957.84 A theater actor, Valdemarin earned a living as an employee of the national railways when he entered the contest as an expert of Westerns; at the end, he won five million lira and a film contract, as well as the attention of fans enamored with his looks.85 When he participated in the AIED initiative, Valdemarin’s fame as an actor in films, television serials, and photoromances was established (he was also a spokesman for Alka Seltzer) but many probably remembered him as the handsome man who rose to stardom from an office desk thanks to a quiz. Symbolically, on his first day after the victory, Valdemarin was immortalized as he descended from a train wagon (on which he had not really traveled) in a newsreel produced by the Ministry of Transportation.86 His past certainly gave more validity to Valdemarin’s claims regarding the need for the government to take care of birth control for the sake of the working class to which, once upon a time, he had also belonged.

In conclusion, the case of the AIED campaign is not only relevant because it sheds light on competing social discourses regarding birth control and contraception (especially in relation to sexuality). In addition, the way in which such a campaign was conceived and conducted anticipates what is now a growing trend of celebrities’ involvement in social causes. This trend sheds light on “the societal and cultural embedding of celebrity” in 1970s Italy.87 In other words, the case of the AIED campaign shows how “a long-term term structural development” of “celebritization” took place in those years, in continuity with the ongoing process of modernization (of both society and the media system) taking place since the aftermath of World War II.88 As I showed in the previous chapters, photoromances had been innovating media strategies of production and consumption since the late 1940s, fostering participatory culture and absorbing conventions as much as human capital from other media industries. Collaborating with the AIED in the campaign for birth control, celebrities like Pitagora and Morandi who had already migrated across media platforms by diversifying their activities in the film, television, music, and photoromance industries, also migrated into an area that was not previously associated with fame. Regardless of whether this decision helped boost their popularity or (as in the case of Pitagora) actually damaged their images, the migration of celebrities at work in the AIED campaign signaled an important moment in the history of Italian culture and society, at the forefront of change.