Pentecost

CHARLES GRANDISON FINNEY came to Rochester in September 1830. For six months he preached in Presbyterian churches nearly every night and three times on Sunday, and his audience included members of every sect. During the day he prayed with individuals and led an almost continuous series of prayer meetings. Soon there were simultaneous meetings in churches and homes throughout the village. Pious women went door-to-door praying for troubled souls. The high school stopped classes and prayed. Businessmen closed their doors early and prayed with their families. “You could not go upon the streets,” recalled one convert, “and hear any conversation, except upon religion.”1 By early spring the churches faced the world with a militance and unity that had been unthinkable only months before, and with a boundless and urgent sense of their ability to change society. In the words of its closest student, “ … no more impressive revival has occurred in American history.”2

First, a word on the evangelical plan of salvation. Man is innately evil and can overcome his corrupt nature only through faith in Christ the redeemer—that much is common to Christianity in all its forms. Institutional and theological differences among Christians trace ultimately to varying means of attaining that faith. The Reformation abolished sacred

beings, places, and institutions that had eased the path between the natural and supernatural worlds. Without ritual, without priest-magicians, without divine immanence in an institutional church, Protestants face God across infinite lonely space. They bridge that space through prayer—through the state of absolute selflessness and submission known generally as transcendence. The experience of transcending oneself and this world through prayer is for Protestants direct experience of the Holy Ghost, and it constitutes assurance of salvation, sanctification, and new life.

Prayer, then, is the one means by which a Protestant establishes his relation with God and his assurance that he is one of God’s people. Prayer is a personal relationship between God and man, and the decision whether that relationship is established belongs to God. No Protestants dispute that. But they have argued endlessly on man’s ability to influence the decision. The evangelical position was phrased (and it was understood by its detractors) as an increase in human ability so great that prayer and individual salvation were ultimately voluntary. Hurried notes to Charles Finney’s Rochester sermons insisted: “It should in all cases be required now to repent, now to give themselves up to God, now to say and feel Lord here I am take me, it’s all I can do. And when the sinner can do that … his conversion is attained.”3 “The truth,” he explained, “is employed to influence men, prayer to move God … I do not mean that God’s mind is changed by prayer … But prayer produces such a change in us as renders it consistent for him to do otherwise.”4 To hyper-Calvinists who protested that this filled helpless man with false confidence, Finney shouted, “What is that but telling them to hold on to their rebellion against God? … as though God was to blame for not converting them.”5 The only thing preventing individual conversion was the individual himself.

This reevaluation of human ability caught the evangelicals in a dilemma. But it was a dilemma they had already solved in

practice. Finney and his friends insisted that God granted new life in answer to faithful prayer. But the ability to pray with faith was itself experimental proof of conversion. By definition, the unregenerate could not pray. For Finney there was a clear and obvious way out, a way that he and Rochester Protestants witnessed hundreds of times during the revival winter: “Nothing is more calculated to beget a spirit of prayer, than to unite in social prayer with one who has the spirit himself.”6 That simple mechanism is at the heart of evangelical Protestantism.

Conversion had always ended in prayer and humiliation before God. But ministers had explained the terms of salvation and left terrified sinners to wrestle with it alone. Prayer was transacted in private between a man and his God, and most middle-class Protestants were uncomfortable with public displays of humiliation. As late as 1829, Rochester Presbyterians had scandalized the village when they began to kneel rather than stand at prayer.7 More than their theological implications, Finney’s revival techniques aroused controversy because they transformed conversion from a private to a public and intensely social event. The door-to-door canvass, the intensification of family devotions, prayer meetings that lasted till dawn, the open humiliation of sinners on the anxious bench: all of these transformed prayer and conversion from private communion into spectacular public events.

What gave these events their peculiar force was the immediatist corollary to voluntary conversion. The Reverend Whitehouse of St. Luke’s Church (yes, the Episcopalians too) explained it in quiet terms:

Appeals are addressed to the heart and the appeals are in reference to the present time. And each time the unconverted sinner leaves the house of God without having closed with the terms of the Gospel he rejects the offer of mercy. Had some future time been specified as that in which we were to make a decision

we might listen time after time to the invitations and reject them. But it is expressly said today and now is the accepted time.8

Initially, these pressures fell on the already converted. It was the prayers of Christians that led others to Christ, and it was their failure to pray that sent untold millions into hell. Lay evangelicals seldom explained the terms of salvation in the language of a Reverend Whitehouse—or even of a Charles Finney. But with the fate of their children and neighbors at stake, they carried their awful responsibility to the point of emotional terrorism. Finney tells the story of a woman who prayed while her son-in-law attended an anxious meeting. He came home converted, and she thanked God and fell dead on the spot.9 Everard Peck reported the death of his wife to an unregenerate father-in-law, and told the old man that his dead daughter’s last wish was to see him converted.10 “We are either marching towards heaven or towards hell,” wrote one convert to his sister. “How is it with you?”11

The new measures brought sinners into intense and public contact with praying Christians. Conversion hinged not on private prayer, arbitrary grace, or intellectual choice, but on purposive encounters between people. The secret of the Rochester revival and of the attendant transformation of society lay ultimately in the strategy of those encounters.

While Finney led morning prayer meetings, pious women visited families. Reputedly they went door-to-door. But the visits were far from random. Visitors paid special attention to the homes of sinners who had Christian wives, and they arrived in the morning hours when husbands were at work. Finney himself found time to pray with Melania Smith, wife of a young physician. The doctor was anxious for his soul, but sickness in the village kept him busy and he was both unable to pray and unwilling to try. But his wife prayed and tormented him constantly, reminding him of “the woe which is

denounced against the families which call not on the Name of the Lord.”12 Soon his pride broke and he joined her as a member of Brick Presbyterian Church. Finney’s wife, Lydia, made a bolder intrusion into the home of James Buchan, a merchant-tailor and a Roman Catholic whose wife, Caroline, was a Presbyterian. Buchan, with what must have been enormous self-restraint, apologized for having been out of the house, thanked Finney for the tract, and invited him and his wife to tea.13 (It is not known whether Finney accepted the invitation, but this was one bit of family meddling which may have backfired. In 1833 Caroline Buchan withdrew from the Presbyterian Church and converted to Catholicism.) In hundreds of cases the strategy of family visits worked. As the first converts fell, the Observer announced with satisfaction that the largest group among them was”young heads of families.“14

Revival enthusiasm began with the rededication of church members and spread to the people closest to them. Inevitably, much of it flowed through family channels. Finney claimed Samuel D. Porter, for instance, as a personal conquest. But clearly he had help. Porter was an infidel, but his sister in Connecticut and his brother-in-law Everard Peck were committed evangelicals. Porter came under a barrage of family exhortation, and in January Peck wrote home that “Samuel is indulging a trembling hope …” He remained the object of family prayer for eight more months before hope turned into assurance. Then he joined his sister and brother-in-law in praying for the soul of their freethinking father.15 The realtor Bradford King left another record of evangelism within and between related households. After weeks of social prayer and private agony, he awoke and heard himself singing, “I am going to the Kingdom will you come along with me.” He testified at meeting the next day, but did not gain assurance until he returned home and for the first time prayed with his family. He rose and “decided that as for me & my house we would serve the Lord.” Immediately King turned newfound powers

on his brother’s house in nearby Bloomfield. After two months of visiting and prayer he announced, “We had a little pentecost at brothers … all were praising and glorifying God in one United Voice.”16 The revival made an evangelist of every convert, and most turned their power on family members.

Charles Finney’s revival was based on group prayer. It was a simple, urgent activity that created new hearts in hundreds of men and women, and it generated—indeed it relied upon—a sense of absolute trust and common purpose among participants. The strengthening of family ties that attended the revival cannot be overestimated. But it was in prayer meetings and evening services that evangelism spilled outside old social channels, laying the basis for a transformed and united Protestant community.

Bradford King had no patience for “Old Church Hipocrites who think more of their particular denomination than Christ Church,”17 and his sentiments were rooted in an astonishing resolution of old difficulties. Presbyterians stopped fighting during the first few days, and peace soon extended to the other denominations. Before the first month was out, Finney marveled that”Christians of every denomination generally seemed to make common cause, and went to work with a will, to pull sinners out of the fire.“18 The most unexpected portent came in October, when the weight of a crowded gallery spread the walls and damaged the building at First Church. Vestrymen at St. Paul’s—most of them former Masons and bitter enemies of the Presbyterians—let that homeless congregation into their church.19 But it was in prayer meetings and formal services that the collective regeneration of a fragmented churchgoing community took place, for it was there that”Christians of different denominations are seen mingled together in the sanctuary on the Sabbath, and bowing at the same altar in the social prayer meeting.“20

Crowded prayer meetings were held almost every night from September until early March, and each of them was

managed carefully. When everyone was seated the leader read a short verse dealing with the object of prayer. Satisfied that everyone understood and could participate, he called on those closest to the spirit. These prayed aloud, and within minutes all worldly thoughts were chased from the room. (Finney knew that the chemistry of prayer worked only when everyone shared in it, and he discouraged attendance by scoffers, cranks, and the merely curious.) Soon sinners grew anxious; some of them broke into tears, and Christians came close to pray with them. Then followed the emotional displays that timid ministers had feared, but which they accepted without a whimper during the revival winter. In October Artemissia Perkins prayed with her fiancé in Brick Church. Suddenly her voice rose above the others, and over and over she prayed, “Blessed be the Name of Jesus,” while her future husband, her neighbors, and people who never again could be strangers watched and participated in the awesome work.21 It was in hundreds of encounters such as this that the revival shattered old divisions and laid the foundation for moral community among persons who had been strangers or enemies. “I know this is all algebra to those who have never felt it,” Finney explained. “But to those who have experienced the agony of wrestling, prevailing prayer, for the conversion of a soul, you may depend on it, that soul … appears as dear as a child is to the mother who brought it forth with pain.”22

At formal services this mechanism took on massive proportions. 23 During services Christians gathered in other churches and nearby homes to pray for the evangelist’s success. Sometimes crowds of people who could not find seats in the house prayed outside in the snow. Downstairs the session room was packed, and every break in the lecture was punctuated by the rise and fall of prayer.

Inside, every seat was filled. People knelt in the aisles and doorways. Finney reserved seats near the pulpit for anxious sinners—not random volunteers, but prominent citizens who

had spoken with him privately. None sat on the anxious bench who was not almost certain to fall. Separated from the regenerate and from hardened sinners, their conversions became grand public spectacles. In the pulpit, Finney preached with enormous power, but with none of the excesses some people expected. He had dropped a promising legal career to enter the ministry, and his preaching demonstrated formidable courtroom skills, not cheap theatrics. True, he took examples from everyday experience and spoke in folksy, colloquial terms. (With what may have been characteristic modesty, he reminded his listeners that Jesus had done the same.) Most of his lectures lasted an hour, but it was not uncommon for a packed church to listen twice that long “without the movement of a foot.” When he gestured at the room, people ducked as if he were throwing things. In describing the fall of sinners he pointed to the ceiling, and as he let his finger drop people in the rear seats stood to watch the final entry into hell. Finney spoke directly to the anxious bench in front of him, and at the close of the lecture he demanded immediate repentance and prayer. Some of Rochester’s first citizens humbled themselves on the anxious bench, sweating their way into heaven surrounded by praying neighbors. It was the most spectacular of the evangelist’s techniques, and the most unabashedly communal.

Charles Finney’s revival created a community of militant evangelicals that would remake society and politics in Rochester. The work of that community will fill the remainder of this book. But now it is time to keep promises made in the Introduction, to attempt a systematic explanation of Finney’s triumph at Rochester. The pages that follow isolate the individuals who joined churches while Finney was in town, then locate experiences that they shared and that explain why they and

not others were ripe for conversion in 1830—31. Insofar as the revival can be traced to its social origins, I shall consider it traceable to those experiences.

Finney claimed to have converted “the great mass of the most influential people” in Rochester.24 The Observer agreed that new church members included most of the town’s “men of wealth, talents, and influence—those who move in the highest circles of society,”25 and church records reinforce those claims. Table 3 compares the occupational status of Finney’s male converts with that of men who joined churches in the years 1825—29. (Pre-revival figures are limited to the four years surrounding the tax list of 1827. Occupations of Finney converts are derived from the 1830 assessment rolls. Thus each occupation in the table is measured within two years of the time of conversion.)

TABLE 3. OCCUPATIONS OF THE NEW MALE ADMITTANTS TO ROCHESTER PROTESTANT CHURCHES IN THE LATE 1820s, AND IN THE REVIVAL OF 1830—31 (PERCENTAGES)

| year of admission | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1825—29 | 1830—31 | |

| (N=85) | (N=170) | |

| businessman-professional | 22 | 19 |

| shopkeeper-petty proprietor | 14 | 11 |

| master craftsman | 16 | 26 |

| clerical employee | 12 | 10 |

| journeyman craftsman | 24 | 22 |

| laborer-semiskilled | 13 | 12 |

| NOTE: The 1825—29 figures are derived from the tax list and directory of 1827. Figures for the years 1830—31 are derived from the 1830 tax list and the directories of 1827 and/or 1834. To ensure that these men were in Rochester when the tax list was compiled, inclusion is limited to those who appear in the 1827 directory or the 1830 census. | ||

Both in the 1820s and in the revival of 1830—31, new church members came disproportionately from among businessmen, professionals, and master workmen. During the Finney revival

conversions multiplied dramatically within every group. But the center of enthusiasm shifted from the stores and offices to the workshops. Indeed it is the sharp increase in conversions among master craftsmen that accounts for slight declines in every other group. Whatever the problems that prepared the ground for Finney’s triumph, they were experienced most strongly by master workmen.

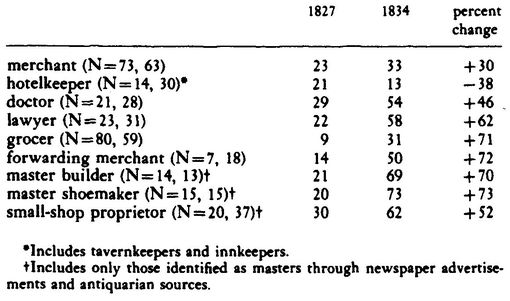

TABLE 4. PERCENT PROTESTANT CHURCH MEMBERS AMONG SELECTED PROPRIETORS, 1827—34

Table 4 begins the attempt to infer just what those problems were. The table isolates specific occupations within the business community and calculates the percentage of church members within them in 1827 and again in 1834. Increases were most spectacular among master craftsmen and manufacturers, but there were significant variations within that group. Master builders and shoemakers had made dramatic breaks with the traditional organization of work, and with customary relations between masters and journeymen. The proportions of church members among them increased 70 percent and 73 percent, respectively. Proprietors of the small indoor workshops participated in the revival, but their increase was a less

impressive 51 percent. Change in the operations they controlled came more slowly. They hired relatively few journeymen, and they continued into the 1830s to incorporate many of those men into their homes.

Among white-collar proprietors, lawyers, forwarding merchants, and grocers made the greatest gains: 62 percent, 72 percent, and 71 percent, respectively. Rochester was the principal shipping point on the Erie Canal, and most boats operating on the canal belonged to Rochester forwarders. It was their boat crews who were reputedly the rowdiest men in an unruly society, and it was the forwarders who had been the chief target of the Sabbatarian crusade. Grocers were another white-collar group with peculiarly close ties to the working class. The principal retailers of liquor, they were closely regulated by the village trustees. In 1832 the trustees not only doubled the price of grocery licenses but began looking into the moral qualifications of applicants.26 The increased religiosity among grocers (as well as the decline in the total number of men in that occupation) reflects that fact. Reformers had branded forwarders and grocers the supporters both of the most dangerous men in society and of their most dangerous habits. While they had resisted attacks on their livelihood, grocers and boat owners could not but agree to their complicity in the collapse of old social forms. Most of them remained outside the churches. But a startlingly increased minority joined with master workmen and cast their lots with Jesus.

With these occupations removed, the revival among white-collar proprietors was weak. Doctors and merchants had only tenuous links with the new working class, and little personal responsibility for the collapse of the late 1820s. Increases among them were 46 percent and 30 percent, respectively. Hotelkeepers in particular were divorced from contact with workingmen, for they were dependent for their livelihoods on the more well-to-do canal travelers. Church membership

among hotelkeepers actually declined 38 percent during the revival years. (The one remaining occupation—the law—was a special case: the increase was 62 percent. No doubt part of the explanation lies in Finney himself, who was a former attorney and took special pride in the conversion of lawyers. But perhaps more important is the fact that many lawyers were politicians, and in the 1830s resistance to the churches was political suicide.)

With few exceptions, then, Charles Finney’s revival was strongest among entrepreneurs who bore direct responsibility for disordered relations between classes. And they were indeed responsible. The problem of social class arose in towns and cities all over the northern United States after 1820. It would be easy to dismiss it as a stage of urban-industrial growth, a product of forces that were impersonal and inevitable. In some ways it was. But at the beginning the new relationship between master and wage earner was created by masters who preferred money and privacy to the company of their workmen and the performance of old patriarchal duties. Available evidence suggests that it was precisely those masters who filled Finney’s meetings.

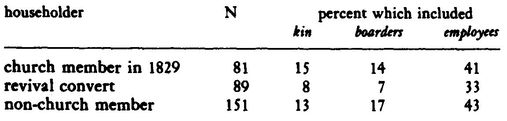

TABLE 5. COMPOSITION OF HOUSEHOLDS HEADED BY PROPRIETORS IN 1827, BY RELIGIOUS STATUS OF HOUSEHOLDERS

Perhaps more than any other act, the removal of workmen from the homes of employers created an autonomous working class. Table 5 compares households headed in 1827 by proprietors who joined churches during the revival with those headed by non-church members and by men who belonged to

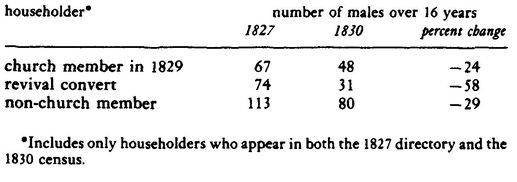

churches before the revival. Finney’s converts kept fewer workmen in their families than did other proprietors, suggesting either that they had removed many of those men or that they had never allowed them into their homes. Table 6 traces households that included “extra” adult men in 1827 over the next three years. The table is compiled from the 1830 census. That document names heads of households and identifies others by age and sex. By counting males over the age of sixteen (the age at which men were included in the 1827 directory, and thus in Table 5), we may trace the broadest outlines of household change in the years immediately preceding the revival. Most proprietors thinned their families between 1827 and 1830. But while old church members and those who stayed outside the churches removed one in four adult men, converts cut their number by more than half.27 Thus the analyses of occupations and of household structure point clearly to one conclusion: Finney’s converts were entrepreneurs who had made more than their share of the choices that created a free-labor economy and a class-bounded society in Rochester.

TABLE 6. CHANGES IN THE COMPOSITION OF HOUSEHOLDS HEADED BY PROPRIETORS, 1827—30, BY RELIGIOUS STATUS OF HOUSEHOLDERS

The transformation began in the workshops, but it was not contained there. For in removing workmen the converts altered their own positions within families. The relative absence of even boarders and distant kin in their homes suggests a concern with domestic privacy. And within those families

housewives assumed new kinds of moral authority. The organization of prayer meetings, the pattern of family visits, and bits of evidence from church records suggest that hundreds of conversions culminated when husbands prayed with their wives. Women formed majorities of the membership of every church at every point in time. But in every church, men increased their proportion of the communicants during revivals, indicating that revivals were family experiences and that women were converting their mean.28 In 1830-31 fully 65 percent of male converts were related to prior members of their churches (computed from surnames within congregations). Traditionalists considered Finney’s practice of having women and men pray together the most dangerous of the new measures, for it implied new kinds of equality between the sexes. Indeed some harried husbands recognized the revival as subversive of their authority over their wives. A man calling himself Anticlericus complained of Finney’s visit to his home:

He stuffed my wife with tracts, and alarmed her fears, and nothing short of meetings, night and day, could atone for the many fold sins my poor, simple spouse had committed, and at the same time, she made the miraculous discovery, that she had been “unevenly yoked.” From this unhappy period, peace, quiet, and happiness have fled from my dwelling, never, I fear, to return.29

The evangelicals assigned crucial religious duties to wives and mothers. In performing those duties, women rose out of old subordinate roles and extended their moral authority within families. Finney’s male converts were driven to religion because they had abdicated their roles as eighteenth-century heads of households. In the course of the revival, their wives helped to transform them into nineteenth-century husbands.30

Charles Finney’s revival enlarged every Protestant church, broke down sectarian boundaries, and mobilized a religious community that had at its disposal enormous economic power. Motives which determined the use of that power derived from the revival, and they were frankly millenarian.

As Rochester Protestants looked beyond their community in 1831, they saw something awesome. For news of Finney’s revival had helped touch off a wave of religious enthusiasm throughout much of the northern United States. The revival moved west into Ohio and Michigan, east into Utica, Albany, and the market towns of inland New England. Even Philadelphia and New York City felt its power.31 Vermont’s congregational churches grew by 29 percent in 1831. During the same twelve months the churches of Connecticut swelled by over a third.32 After scanning reports from western New York, the Presbyterian General Assembly announced in wonder that”the work has been so general and thorough, that the whole customs of society have changed.“33 Never before had so many Americans experienced religion in so short a time. Lyman Beecher, who watched the excitement from Boston, declared that the revival of 1831 was the greatest revival of religion that the world had ever seen.34

Rochester Protestants saw conversions multiply and heard of powerful revivals throughout Yankee Christendom. They saw divisions among themselves melt away, and they began to sense that the pre-millennial unanimity was at hand—and that they and people like them were bringing it about. They had converted their families and neighbors through prayer. Through ceaseless effort they could use the same power to convert the world. It was Finney himself who told them that “if they were united all over the world the Millennium might be brought about in three months.”35 He did not mean that Christ was coming to Rochester. The immediate and gory

millennium predicted in Revelation had no place in evangelical thinking. Utopia would be realized on earth, and it would be made by God with the active and united collaboration of His people. It was not the physical reign of Christ that Finney predicted but the reign of Christianity. The millennium would be accomplished when sober, godly men—men whose every step was guided by a living faith in Jesus—exercised power in this world. Clearly, the revival of 1831 was a turning point in the long struggle to establish that state of affairs. American Protestants knew that, and John Humphrey Noyes later recalled that “in 1831, the whole orthodox church was in a state of ebullition in regard to the Millennium.”36 Rochester evangelicals stood at the center of that excitement.

After 1831 the goal of revivals was the christianization of the world. With that at stake, membership in a Protestant church entailed new kinds of personal commitment. Newcomers to Brick Presbyterian Church in the 1820s had agreed to obey the laws of God and of the church, to treat fellow members as brothers, and “to live as an humble Christian.” Each new convert was told that “renouncing all ungodliness and every worldly lust, you give up your all, soul and body, to be the Lord’s, promising to walk before him in holiness and love all the days of your life.”37 Not easy requirements, certainly, but in essence personal and passive. With the Finney revival, the ingrown piety of the 1820s turned outward and aggressive. In 1831 Brick Church rewrote its covenant, and every member signed this evangelical manifesto:

We [note that the singular “you” has disappeared] do now, in the presence of the Eternal God, and these witnesses, covenant to be the Lord’s. We promise to renounce all the ways of sin, and to make it the business of our life to do good and promote the declarative glory of our heavenly Father. We promise steadily and devoutly to attend upon the institutions and ordinances of Christ as administered in this church, and to submit ourselves to its direction and discipline, until our present relation shall be

regularly dissolved. We promise to be kind and affectionate to all the members of this church, to be tender of their character, and to endeavor to the utmost of our ability, to promote their growth in grace. We promise to make it the great business of our life to glorify God and build up the Redeemer’s Kingdom in this fallen world, and constantly to endeavor to present our bodies a living sacrifice, holy and acceptable to Him.38

In that final passage, the congregation affirmed that its actions —both individually and in concert—were finally meaningful only in relation to the Coming Kingdom. Everything they did tended either to bring it closer or push it farther away.

Guiding the new activism was a revolution in ideas about human ability. The Reverend William James of Brick Church had insisted in 1828 that most men were innately sinful. Christians could not change them, but only govern their excesses through “a system of moral regulations, founded upon the natural relations between moral beings, and having for its immediate end the bappiness of the community.”39 We have seen, however, that certain of those “natural relations” were in disarray, and that the businessmen and master workmen who were expected to govern within them were the most active participants in the revival. Evangelical theology absolved them of responsibility by teaching that virtue and order were products not of external authority but of choices made by morally responsible individuals. Nowhere, perhaps, was this put more simply than in the Sunday schools. In the 1820s children had been taught to read and then forced to memorize huge parts of the Bible. (Thirteen-year-old Jane Wilson won a prize in 1823 when she committed a numbing 1,650 verses to memory.)40 After 1831 Sunday-school scholars stopped memorizing the Bible. The object now was to have them study a few verses a week and to come to an understanding of them, and thus to prepare themselves for conversion and for “an active and useful Christian life.”41 Unregenerate persons were no longer to be disciplined by immutable authority and through fixed social relationships.

They were free and redeemable moral agents, accountable for their actions, capable of accepting or rejecting God’s promise. It was the duty of Christian gentlemen not to govern them and accept responsibility for their actions but to educate them and change their hearts.

William Wisner, pastor at Brick Church during these years, catalogued developments that were “indispensably necessary to the bringing of millennial glory.” First, of course, was more revivals. Second, and tied directly to the first, was the return of God’s people to the uncompromising personal standards of the primitive Christians and Protestant martyrs.42 For the public and private behavior of converts advertised what God had done for them. If a Christian drank or broke the Sabbath or cheated his customers or engaged in frivolous conversation, he weakened not only his own reputation but the awesome cause he represented. While Christian women were admonished to discourage flattery and idle talk and to bring every conversation onto the great subject, troubled businessmen were actually seen returning money to families they had cheated.43 Isaac Lyon, half-owner of the Rochester Woolen Mills, was seen riding a canal boat on Sunday in the fall of 1833. Immediately he was before the trustees of his church. Lyon was pardoned after writing a confession into the minutes and reading it to the full congregation. He confessed that he had broken the eighth commandment. But more serious, he admitted, was that his sin was witnessed by others who knew his standing in the church and in the community, and for whom the behavior of Isaac Lyon reflected directly on the evangelical cause. He had shamed Christ in public and given His enemies cause to celebrate.44

Finney’s revival had, however, centered among persons whose honesty and personal morals were beyond question before they converted. Personal piety and circumspect public behavior were at bottom means toward the furtherance of revivals. At the moment of rebirth, the question came to each

of them: “Lord, what wilt thou have me do?” The answer was obvious: unite with other Christians and convert the world. The world, however, contained bad habits, people, and institutions that inhibited revivals and whose removal must precede the millennium. Among church members who had lived in Rochester in the late 1820s, the right course of action was clear. With one hand they evangelized among their own unchurched poor. With the other they waged an absolutist and savage war on strong drink.

On New Year’s Eve of the revival winter, Finney’s co-worker Theodore Weld delivered a four-hour temperance lecture at First Presbyterian Church. Weld began by describing a huge open pit at his right hand, and thousands of the victims of drink at his left. First he isolated the most hopeless—the runaway fathers, paupers, criminals, and maniacs—and marched them into the grave. He moved higher and higher into society, until only a few well-dressed tipplers remained outside the grave. Not even these were spared. While the audience rose to its feet the most temperate drinkers, along with their wives and helpless children, were swallowed up and lost. Weld turned to the crowd and demanded that they not only abstain from drinking and encourage the reform of others but that they unite to stamp it out. They must not drink or sell liquor, rent to a grogshop, sell grain to distillers, or patronize merchants who continued to trade in ardent spirits. They must, in short, utterly disengage from the traffic in liquor and use whatever power they had to make others do the same. A packed house stood silent.45

The Reverend Penney rose from his seat beside the Methodist and Baptist preachers and demanded that vendors in the audience stop selling liquor immediately. Eight or ten did so on the spot, and the wholesale grocers retired to hold a meeting of their own. The next day Elijah and Albert Smith, Baptists who owned the largest grocery and provisions warehouse in the city, rolled their stock of whiskey out onto the sidewalk.

While cheering Christians and awestruck sinners looked on, they smashed the barrels and let thousands of gallons of liquid poison run out onto Exchange Street.46

Within a week, Everard Peck wrote home that “the principal merchants who have traded largely in ardent spirits are about abandoning this unholy traffic & we almost hope to see this deadly poison expelled from our village.”47 The performance of the Smith brothers was being repeated throughout Rochester. Sometimes wealthy converts walked into groceries, bought up all the liquor, and threw it away. A few grocers with a fine taste for symbolism poured their whiskey into the Canal. Even grocers who stayed outside the churches found that whiskey on their shelves was bad for business. The firm of Rossiter and Knox announced that it was discontinuing the sale of whiskey, but “not thinking it a duty to ‘feed the Erie Canal’ with their property, offer to sell at cost their whole stock of liquors …”48 Those who resisted were refused advertising space in some newspapers,49 and in denying the power of a united evangelical community they toyed with economic ruin. S. P. Needham held out for three years, but in 1834 he announced that he planned to liquidate his stock of groceries, provisions, and liquors and leave Rochester. “Church Dominancy,” he explained, “has such influence over this community that no honest man can do his own business in his own way …”50

Almost immediately, Weld’s absolutist temperance pledge became a condition of conversion—the most visible symbol of individual rebirth.51 The teetotal pledge was only the most forceful indication of church members’ willingness to use whatever power they had to coerce others into being good, or at least to deny them the means of being bad. While whiskey ran into the gutters, two other symbols of the riotous twenties disappeared. John and Joseph Christopher, both of them new Episcopalians, bought the theater next door to their hotel, closed it, and had it reopened as a livery stable. The Presbyterian

Sprague brothers bought the circus building and turned it into a soap factory. Increasingly, the wicked had no place to go.52

These were open and forceful attacks on the leisure activities of the new working class, something very much like class violence. But Christians waged war on sin, not workingmen. Alcohol, the circus, the theater, and other workingmen’s entertainments were evil because they wasted men’s time and clouded their minds and thus blocked the millennium. Evangelicals fought these evils in order to prepare society for new revivals. It was missionary work, little more. And in the winter following Finney’s departure, it began to bear fruit.