Fascism

Preview

The term ‘fascism’ derives from the Italian word fasces, meaning a bundle of rods with an axe-blade protruding that signified the authority of magistrates in Imperial Rome. By the 1890s, the word fascia was being used in Italy to refer to a political group or band, usually of revolutionary socialists. It was not until Mussolini employed the term to describe the paramilitary armed squads he formed during and after the First World War that fascismo acquired a clearly ideological meaning.

The defining theme of fascism is the idea of an organically unified national community, embodied in a belief in ‘strength through unity’. The individual, in a literal sense, is nothing; individual identity must be entirely absorbed into the community or social group. The fascist ideal is that of the ‘new man’, a hero, motivated by duty, honour and self-sacrifice, prepared to dedicate his life to the glory of his nation or race, and to give unquestioning obedience to a supreme leader. In many ways, fascism constitutes a revolt against the ideas and values that dominated western political thought from the French Revolution onwards; in the words of the Italian fascists’ slogan: ‘1789 is Dead’. Values such as rationalism, progress, freedom and equality were thus overturned in the name of struggle, leadership, power, heroism and war. Fascism therefore has a strong ‘anti-character’: it is anti-rational, anti-liberal, anti-conservative, anti-capitalist, anti-bourgeois, anti-communist and so on.

Fascism has nevertheless been a complex historical phenomenon, encompassing, many argue, two distinct traditions. Italian fascism was essentially an extreme form of statism that was based on absolute loyalty towards a ‘totalitarian’ state. In contrast, German fascism, or Nazism, was founded on racial theories, which portrayed the Aryan people as a ‘master race’ and advanced a virulent form of anti-Semitism.

Whereas liberalism, conservatism and socialism are nineteenth-century ideologies, fascism is a child of the twentieth century, some would say specifically of the period between the two world wars. Indeed, fascism emerged very much as a revolt against modernity, against the ideas and values of the Enlightenment and the political creeds that it spawned. The Nazis in Germany, for instance, proclaimed that ‘1789 is Abolished’. In Fascist Italy, slogans such as ‘Believe, Obey, Fight’ and ‘Order, Authority, Justice’ replaced the more familiar principles of the French Revolution, ‘Liberty, Equality and Fraternity’. Fascism came not only as a ‘bolt from the blue’, as O’Sullivan (1983) put it, but also attempted to make the political world anew, quite literally to root out and destroy the inheritance of conventional political thought.

Although the major ideas and doctrines of fascism can be traced back to the nineteenth century, they were fused together and shaped by World War I and its aftermath, in particular by a potent mixture of war and revolution. Fascism emerged most dramatically in Italy and Germany. In Italy, a Fascist Party was formed in 1919, its leader, Benito Mussolini (see p. 213), was appointed prime minister in 1922 against the backdrop of the March on Rome (see p. 206), and by 1926 a one-party fascist state had been established. The National Socialist German Workers’ Party, known as the Nazis, was also formed in 1919 and, under the leadership of Adolf Hitler (see p. 213), it consciously adopted the style of Mussolini’s Fascists. Hitler was appointed German chancellor in 1933 and in little over a year had turned Germany into a Nazi dictatorship. During the same period, democracy collapsed or was overthrown in much of Europe, often being supplanted by right-wing, authoritarian or openly fascist regimes, especially in eastern Europe. Regimes that bear some relationship to fascism have also developed outside Europe, notably in the 1930s in Imperial Japan and in Argentina under Perón (1945–55).

The origins and meaning of fascism have provoked considerable historical interest and often fierce disagreements. No single factor can, on its own, account for the rise of fascism; rather, fascism emerged out of a complex range of historical forces that were present during the inter-war period. In the first place, democratic government had only recently been established in many parts of Europe, and democratic political values had not replaced older, autocratic ones. Moreover, democratic governments, representing a coalition of interests or parties, often appeared weak and unstable when confronted by economic or political crises. In this context, the prospect of strong leadership brought about by personal rule cast a powerful appeal. Second, European society had been disrupted by the experience of industrialization, which had particularly threatened a lower middle class of shopkeepers, small businessmen, farmers and craftsmen, who were squeezed between the growing might of big business, on the one hand, and the rising power of organized labour, on the other. Fascist movements drew their membership and support largely from such lower middle-class elements. In a sense, fascism was an ‘extremism of the centre’ (Lipset, 1983), a revolt of the lower middle classes, a fact that helps to explain the hostility of fascism to both capitalism and communism.

Third, the period after World War I was deeply affected by the Russian Revolution and the fear among the propertied classes that social revolution was about to spread throughout Europe. Fascist groups undoubtedly drew both financial and political support from business interests. As a result, Marxist historians have interpreted fascism as a form of counter-revolution, an attempt by the bourgeoisie to cling on to power by lending support to fascist dictators. Fourth, the world economic crisis of the 1930s often provided a final blow to already fragile democracies. Rising unemployment and economic failure produced an atmosphere of crisis and pessimism that could be exploited by political extremists and demagogues. Finally, World War I had failed to resolve international conflicts and rivalries, leaving a bitter inheritance of frustrated nationalism and the desire for revenge. Nationalist tensions were strongest in those ‘have not’ nations that had either, like Germany, been defeated in war, or had been deeply disappointed by the terms of the Versailles peace settlement; for example, Italy and Japan. In addition, the experience of war itself had generated a particularly militant form of nationalism and imbued it with militaristic values.

Fascist regimes were not overthrown by popular revolt or protest but by defeat in World War II. Since 1945, fascist movements have achieved only marginal success, encouraging some to believe that fascism was a specifically inter-war phenomenon, linked to the unique combination of historical circumstances that characterized that period (Nolte, 1965). Others, however, regard fascism as an ever-present danger, seeing its roots in human psychology, or as Erich Fromm (1984) called it, ‘the fear of freedom’. Modern civilization has produced greater individual freedom but, with it, the danger of isolation and insecurity. At times of crisis, individuals may therefore flee from freedom, seeking security in submission to an all-powerful leader or a totalitarian state. Political instability or an economic crisis could therefore produce conditions in which fascism could revive. Fears, for example, have been expressed about the growth of neofascism in parts of eastern Europe following the collapse of communist rule (1989–91). The prospects for fascism in the light of the advance of globalization (see p. 20) are discussed in the final section of the chapter.

Core themes: strength through unity

Fascism is a difficult ideology to analyse, for at least two reasons. First, it is sometimes doubted if fascism can be regarded, in any meaningful sense, as an ideology. Lacking a rational and coherent core, fascism appears to be, as Hugh Trevor-Roper put it, ‘an ill-assorted hodge-podge of ideas’ (Woolf, 1981). Hitler, for instance, preferred to describe his ideas as a Weltanschauung, rather than a systematic ideology. In this sense, a world-view is a complete, almost religious, set of attitudes that demand commitment and faith, rather than invite reasoned analysis and debate. Fascists were drawn to ideas and theories less because they helped to make sense of the world, in rational terms, but more because they had the capacity to stimulate political activism. Fascism may thus be better described as a political movement or even a political religion, rather than an ideology.

WELTANSCHAUUNG

(German) Literally, a ‘world-view’; a distinctive, even unique, set of presuppositions that structure how a people understands and engages emotionally with the world.

Second, so complex has fascism been as a historical phenomenon that it has been difficult to identify its core principles or a ‘fascist minimum’, sometimes seen as generic fascism. Where does fascism begin and where does it end? Which movements and regimes can be classified as genuinely fascist? Doubt, for instance, has been cast on whether Imperial Japan, Vichy France, Franco’s Spain, Perón’s Argentina and even Hitler’s Germany can be classified as fascist. Controversy surrounds the relationship between modern radical right groups, such as the Front National in France and the British National Party in the UK, and fascism: are these groups ‘fascist’, ‘neofascist’, ‘post-fascist’, ‘extreme nationalist’ or whatever?

Among the attempts to define the ideological core of fascism have been Ernst Nolte’s (1965) theory that it is a ‘resistance to transcendence’, A. J. Gregor’s (1969) belief that it looks to construct ‘the total charismatic community’, Roger Griffin’s (1993) assertion that it constitutes ‘palingenetic ultranationalism’ (palingenesis meaning rebirth) and Roger Eatwell’s (2003) assertion that it is a ‘holistic-national radical Third Way’. While each of these undoubtedly highlights an important feature of fascism, it is difficult to accept that any single-sentence formula can sum up a phenomenon as resolutely shapeless as fascist ideology. Perhaps the best we can hope to do is to identify a collection of themes that, when taken together, constitute fascism’s structural core. The most significant of these include:

•anti-rationalism

•struggle

•leadership and elitism

•socialism

•ultranationalism.

Anti-rationalism

Although fascist political movements were born out of the upheavals that accompanied World War I, they drew on ideas and theories that had been circulating since the late nineteenth century. Among the most significant of these were anti-rationalism and the growth of counter-Enlightenment thinking generally. The Enlightenment, based on the ideas of universal reason, natural goodness and inevitable progress, was committed to liberating humankind from the darkness of irrationalism and superstition. In the late nineteenth century, however, thinkers had started to highlight the limits of human reason and draw attention to other, perhaps more powerful, drives and impulses. For instance, Friedrich Nietzsche (see p. 212) proposed that human beings are motivated by powerful emotions, their ‘will’ rather than the rational mind, and in particular by what he called the ‘will to power’. In Reflections on Violence ([1908] 1950), the French syndicalist Georges Sorel (1847–1922) highlighted the importance of ‘political myths’, and especially the ‘myth of the general strike’, which are not passive descriptions of political reality but ‘expressions of the will’ that engaged the emotions and provoked action. Henri Bergson (1859–1941), the French philosopher, advanced the theory of vitalism. This suggests that the purpose of human existence is therefore to give expression to the life force, rather than to allow it to be confined or corrupted by the tyranny of cold reason or soulless calculation.

VITALISM

The theory that living organisms derive their characteristic properties from a universal ‘life-force’; vitalism implies an emphasis upon instinct and impulse rather than intellect and reason.

Although anti-rationalism does not necessarily have a right-wing or proto-fascist character, fascism gave political expression to the most radical and extreme forms of counter-Enlightenment thinking. Anti-rationalism has influenced fascism in a number of ways. In the first place, it gave fascism a marked anti-intellectualism, reflected in a tendency to despise abstract thinking and revere action. For example, Mussolini’s favourite slogans included ‘Action not Talk’ and ‘Inactivity Is Death’. Intellectual life was devalued, even despised: it is cold, dry and lifeless. Fascism, instead, addresses the soul, the emotions, the instincts. Its ideas possess little coherence or rigour, but seek to exert a mythic appeal. Its major ideologists, in particular Hitler and Mussolini, were essentially propagandists, interested in ideas and theories largely because of their power to elicit an emotional response and spur the masses to action. Fascism thus practises the ‘politics of the will’.

Second, the rejection of the Enlightenment gave fascism a predominantly negative or destructive character. Fascists, in other words, have often been clearer about what they oppose than what they support. Fascism thus appears to be an ‘anti-philosophy’: it is anti-rational, anti-liberal, anti-conservative, anti-capitalist, anti-bourgeois, anti-communist and so on. In this light, some have portrayed fascism as an example of nihilism. Nazism, in particular, has been described as a ‘revolution of nihilism’. However, fascism is not merely the negation of established beliefs and principles. Rather, it is an attempt to reverse the heritage of the Enlightenment. It represents the darker underside of the western political tradition, the central and enduring values of which were not abandoned but rather transformed or turned upside-down. For example, in fascism, ‘freedom’ came to mean unquestioning submission, ‘democracy’ was equated with absolute dictatorship, and ‘progress’ implied constant struggle and war. Moreover, despite an undoubted inclination towards nihilism, war and even death, fascism saw itself as a creative force, a means of constructing a new civilization through ‘creative destruction’. Indeed, this conjunction of birth and death, creation and destruction, can be seen as one of the characteristic features of the fascist world-view.

Third, by abandoning the standard of universal reason, fascism has placed its faith entirely in history, culture and the idea of organic community. Such a community is shaped not by the calculations and interests of rational individuals but by innate loyalties and emotional bonds forged by a common past. In fascism, this idea of organic unity is taken to its extreme. The national community, or as the Nazis called it, the Volksgemeinschaft, was viewed as an indivisible whole, all rivalries and conflicts being subordinated to a higher, collective purpose. The strength of the nation or race is therefore a reflection of its moral and cultural unity. This prospect of unqualified social cohesion was expressed in the Nazi slogan, ‘Strength through Unity.’ The revolution that fascists sought was thus ‘revolution of the spirit’, aimed at creating a new type of human being (always understood in male terms). This was the ‘new man’ or ‘fascist man’, a hero, motivated by duty, honour and self-sacrifice, and prepared to dissolve his personality in that of the social whole.

Struggle

The ideas that the UK biologist Charles Darwin (1809–82) developed in On the Origin of Species ([1859] 1972), popularly known as the theory of ‘natural selection’, had a profound effect not only on the natural sciences, but also, by the end of the nineteenth century, on social and political thought. The notion that human existence is based on competition or struggle was particularly attractive in the period of intensifying international rivalry that eventually led to war in 1914. Social Darwinism also had a considerable impact on emerging fascism. In the first place, fascists regarded struggle as the natural and inevitable condition of both social and international life. Only competition and conflict guarantee human progress and ensure that the fittest and strongest will prosper. As Hitler told German officer cadets in 1944, ‘Victory is to the strong and the weak must go to the wall.’ If the testing ground of human existence is competition and struggle, then the ultimate test is war, which Hitler described as ‘an unalterable law of the whole of life’. Fascism is perhaps unique among political ideologies in regarding war as good in itself, a view reflected in Mussolini’s belief that ‘War is to men what maternity is to women.’

NATURAL SELECTION

The theory that species go through a process of random mutations that fits some to survive (and possibly thrive) while others become extinct.

Darwinian thought also invested fascism with a distinctive set of political values, which equate ‘goodness’ with strength, and ‘evil’ with weakness. In contrast to traditional humanist or religious values, such as caring, sympathy and compassion, fascists respect a very different set of martial values: loyalty, duty, obedience and self-sacrifice. When the victory of the strong is glorified, power and strength are worshipped for their own sake. Similarly, weakness is despised and the elimination of the weak and inadequate is positively welcomed: they must be sacrificed for the common good, just as the survival of a species is more important than the life of any single member of that species. Weakness and disability must therefore not be tolerated; they should be removed. This was illustrated most graphically by the programme of eugenics, introduced by the Nazis in Germany, whereby mentally and physically handicapped people were first forcibly sterilized and then, between 1939 and 1941, systematically murdered. The attempt by the Nazis to exterminate European Jewry from 1941 onwards was, in this sense, an example of racial eugenics.

EUGENICS

The theory or practice of selective breeding, achieved either by promoting procreation amongst ‘fit’ members of a species or by preventing procreation by the ‘unfit’.

Finally, fascism’s conception of life as an ‘unending struggle’ gave it a restless and expansionist character. National qualities can only be cultivated through conflict and demonstrated by conquest and victory. This was clearly reflected in Hitler’s foreign policy goals, as outlined in Mein Kampf ([1925] 1969): ‘Lebensraum [living space] in the East’, and the ultimate prospect of world domination. Once in power in 1933, Hitler embarked on a programme of rearmament in preparation for expansion in the late 1930s. Austria was annexed in the Anschluss of 1938; Czechoslovakia was dismembered in the spring of 1939; and Poland invaded in September 1939, pro-voking war with the UK and France. In 1941, Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union. Even when facing imminent defeat in 1945, Hitler did not abandon social Darwinism, but declared that the German nation had failed him and gave orders, never fully carried out, for a fight to the death and, in effect, the annihilation of Germany.

Leadership and elitism

Fascism also stands apart from conventional political thought in its radical rejection of equality. Fascism is deeply elitist and fiercely patriarchal; its ideas were founded on the belief that absolute leadership and elitism are natural and desirable. Human beings are born with radically different abilities and attributes, a fact that emerges as those with the rare quality of leadership rise, through struggle, above those capable only of following. Fascists believe that society is composed, broadly, of three kinds of people. First, and most important, there is a supreme, all-seeing leader who possesses unrivalled authority. Second, there is a ‘warrior’ elite, exclusively male and distinguished, unlike traditional elites, by its heroism, vision and the capacity for self-sacrifice. In Germany, this role was ascribed to the SS, which originated as a bodyguard but developed during Nazi rule into a state within a state. Third, there are the masses, who are weak, inert and ignorant, and whose destiny is unquestioning obedience.

ELITISM

A belief in rule by an elite or minority; elite rule may be thought to be desirable (the elite having superior talents or skills) or inevitable, (egalitarianism simply being impractical).

Such a pessimistic view of the capabilities of ordinary people puts fascism starkly at odds with the ideas of liberal democracy (see p. 40). Nevertheless, the idea of supreme leadership was also associated with a distinctively fascist, if inverted, notion of democratic rule. The fascist approach to leadership, especially in Nazi Germany, was crucially influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche’s idea of the Übermensch, the ‘over-man’ or ‘superman’, a supremely gifted or powerful individual. Most fully developed in Thus Spoke Zarathustra ([1884] 1961), Nietzsche portrayed the ‘superman’ as an individual who rises above the ‘herd instinct’ of conventional morality and lives according to his own will and desires. Fascists, however, turned the superman ideal into a theory of supreme and unquestionable political leadership. Fascist leaders styled themselves simply as ‘the Leader’ – Mussolini proclaimed himself to be Il Duce, while Hitler adopted the title Der Führer – precisely in order to emancipate themselves from any constitutionally defined notion of leadership. In this way, leadership became exclusively an expression of charismatic authority emanating from the leader himself. While constitutional, or, in Max Weber’s term, legal-rational authority operates within a framework of laws or rules, charismatic authority is potentially unlimited. As the leader was viewed as a uniquely gifted individual, his authority was absolute. At the Nuremburg Rallies, the Nazi faithful thus chanted ‘Adolf Hitler is Germany, Germany is Adolf Hitler.’ In Italy, the principle that ‘Mussolini is always right’ became the core of fascist dogma.

CHARISMA

Charm or personal power; the ability to inspire loyalty, emotional dependence or even devotion in others.

LIBERALS believe that authority arises ‘from below’ through the consent of the governed. Though a requirement of orderly existence, authority is rational, purposeful and limited, a view reflected in a preference for legal-rational authority and public accountability.

CONSERVATIVES see authority as arising from natural necessity, being exercised ‘from above’ by virtue of the unequal distribution of experience, social position and wisdom. Authority is beneficial as well as necessary, in that it fosters respect and loyalty, and promotes social cohesion.

SOCIALISTS, typically, are suspicious of authority, which is regarded as implicitly oppressive and generally linked to the interests of the powerful and privileged. Socialist societies have nevertheless endorsed the authority of the collective body, however expressed, as a means of checking individualism and greed.

ANARCHISTS view all forms of authority as unnecessary and destructive, equating authority with oppression and exploitation. Since there is no distinction between authority and naked power, all checks on authority and all forms of accountability are entirely bogus.

FASCISTS regard authority as a manifestation of personal leadership or charisma, a quality possessed by unusually gifted (if not unique) individuals. Such charismatic authority is, and should be, absolute and unquestionable, and is thus implicitly, and possibly explicitly, totalitarian in character.

The ‘leader principle’ (in German, the Führerprinzip), the principle that all authority emanates from the leader personally, thus became the guiding principle of the fascist state. Intermediate institutions such as elections, parliaments and parties were either abolished or weakened to prevent them from challenging or distorting the leader’s will. This principle of absolute leadership was underpinned by the belief that the leader possesses a monopoly of ideological wisdom: the leader, and the leader alone, defines the destiny of his people, their ‘real’ will, their ‘general will’. A Nietzschean theory of leadership thus coincided with a Rousseauian belief in a single, indivisible public interest. In this light, a genuine democracy is an absolute dictatorship, absolutism and popular sovereignty being fused into a form of ‘totalitarian democracy’ (Talmon, 1952). The role of the leader is to awaken the people to their destiny, to transform an inert mass into a powerful and irresistible force. Fascist regimes therefore exhibited populist-mobilizing features that set them clearly apart from traditional dictatorships. Whereas traditional dictatorships aimed to exclude the masses from politics, totalitarian dictatorships set out to recruit them into the values and goals of the regime through constant propaganda and political agitation. In the case of fascist regimes, this was reflected in the widespread use of plebiscites, rallies and popular demonstrations.

TOTALITARIAN DEMOCRACY

An absolute dictatorship that masquerades as a democracy, typically based on the leader’s claim to a monopoly of ideological wisdom.

Socialism

At times, both Mussolini and Hitler portrayed their ideas as forms of ‘socialism’. Mussolini had previously been an influential member of the Italian Socialist Party and editor of its newspaper, Avanti, while the Nazi Party espoused a philosophy it called ‘national socialism’. To some extent, undoubtedly, this represented a cyni-cal attempt to elicit support from urban workers. Nevertheless, despite obvious ideological rivalry between fascism and socialism, fascists did have an affinity for certain socialist ideas and positions. In the first place, lower-middle-class fascist activists had a profound distaste for large-scale capitalism, reflected in a resentment towards big business and financial institutions. For instance, small shopkeepers were under threat from the growth of department stores, the smallholding peasantry was losing out to large-scale farming, and small businesses were increasingly in hock to the banks. Socialist or ‘leftist’ ideas were therefore prominent in German grassroots organizations such as the SA, or Brownshirts, which recruited significantly from among the lower middle classes. Second, fascism, like socialism, subscribes to collectivism (see p. 99), putting it at odds with the ‘bourgeois’ values of capitalism. Fascism places the community above the individual; Nazi coins, for example, bore the inscription ‘Common Good before Private Good’. Capitalism, in contrast, is based on the pursuit of self-interest and therefore threatens to undermine the cohesion of the nation or race. Fascists also despise the materialism that capitalism fosters: the desire for wealth or profit runs counter to the idealistic vision of national regeneration or world conquest that inspires fascists.

Third, fascist regimes often practised socialist-style economic policies designed to regulate or control capitalism. Capitalism was thus subordinated to the ideological objectives of the fascist state. As Oswald Mosley (1896–1980), leader of the British Union of Fascists, put it, ‘Capitalism is a system by which capital uses the nation for its own purposes. Fascism is a system by which the nation uses capital for its own purposes.’ Both the Italian and German regimes tried to bend big business to their political ends through policies of nationalization and state regulation. For example, after 1939, German capitalism was reorganized under Hermann Göring’s Four Year Plan, deliberately modelled on the Soviet idea of Five Year Plans.

However, the notion of fascist socialism has severe limitations. For instance, ‘leftist’ elements within fascist movements, such as the SA in Germany and Sorelian revolutionary syndicalists in Italy, were quickly marginalized once fascist parties gained power, in the hope of cultivating the support of big business. This occurred most dramatically in Nazi Germany, through the purge of the SA and the murder of its leader, Ernst Rohm, in the ‘Night of the Long Knives’ in 1934. Marxists have thus argued that the purpose of fascism was to salvage capitalism rather than to subvert it. Moreover, fascist ideas about the organization of economic life were, at best, vague and sometimes inconsistent; pragmatism (see p. 9), not ideology, determined fascist economic policy. Finally, anti-communism was more prominent within fascism than anti-capitalism. A core objective of fascism was to seduce the working class away from Marxism and Bolshevism, which preached the insidious, even traitorous, idea of international working-class solidarity and upheld the misguided values of cooperation and equality. Fascists were dedicated to national unity and integration, and so wanted the allegiances of race and nation to be stronger than those of social class.

Ultranationalism

Fascism embraced an extreme version of chauvinistic and expansionist nationalism. This tradition regarded nations not as equal and interdependent entities, but as rivals in a struggle for dominance. Fascist nationalism did not preach respect for distinctive cultures or national traditions, but asserted the superiority of one nation over all others. In the explicitly racial nationalism of Nazism this was reflected in the ideas of Aryanism. Between the wars, such militant nationalism was fuelled by an inheritance of bitterness and frustration, which resulted from World War I and its aftermath.

ARYANISM

The belief that the Aryans, or German people, are a ‘master race’, destined for world domination.

Fascism seeks to promote more than mere patriotism (see p. 164); it wishes to establish an intense and militant sense of national identity, which Charles Maurras (see p. 185) called ‘integral nationalism’. Fascism embodies a sense of messianic or fanatical mission: the prospect of national regeneration and the rebirth of national pride. Indeed, the popular appeal that fascism has exerted has largely been based on the promise of national greatness. According to Griffin (1993), the mythic core of generic fascism is the conjunction of the ideas of ‘palingenesis’, or recurrent rebirth, and ‘populist ultranationalism’. All fascist movements therefore highlight the moral bankruptcy and cultural decadence of modern society, but proclaim the possibility of rejuvenation, offering the image of the nation ‘rising phoenix-like from the ashes’. Fascism thus fuses myths about a glorious past with the image of a future characterized by renewal and reawakening, hence the idea of the ‘new’ man. In Italy, this was reflected in attempts to recapture the glories of Imperial Rome; in Germany, the Nazi regime was portrayed as the ‘Third Reich’, in succession to Charlemagne’s ‘First Reich’ and Bismarck’s ‘Second Reich’.

INTEGRAL NATIONALISM

An intense, even hysterical, form of nationalist enthusiasm, in which individual identity is absorbed within the national community.

However, in practice, national regeneration invariably meant the assertion of power over other nations through expansionism, war and conquest. Influenced by social Darwinism and a belief in national and sometimes racial superiority, fascist nationalism became inextricably linked to militarism and imperialism. Nazi Germany looked to construct a ‘Greater Germany’ and build an empire stretching into the Soviet Union – ‘Lebensraum in the East’. Fascist Italy sought to found an African empire through the invasion of Abyssinia in 1934. Imperial Japan occupied Manchuria in 1931 in order to found a ‘co-prosperity’ sphere in a new Japanese-led Asia. These empires were to be autarkic, based on strict self-sufficiency. In the fascist view, economic strength is based on the capacity of the nation to rely solely on resources and energies it directly controls. Conquest and expansionism are therefore a means of gaining economic security as well as national greatness. National regeneration and economic progress are therefore intimately tied up with military power.

AUTARKY

Economic self-sufficiency, brought about either through expansionism aimed at securing markets and sources of raw materials, or by withdrawal from the international economy.

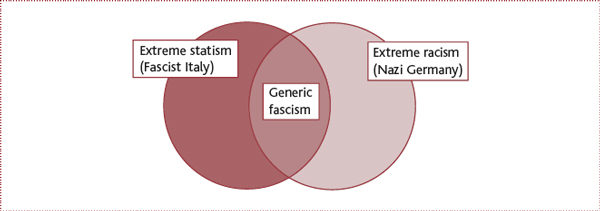

Fascism and the state

Although it is possible to identify a common set of fascist values and principles, Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany nevertheless represented different versions of fascism and were inspired by distinctive and sometimes rival beliefs. Fascist regimes and movements have therefore corresponded to one of two major traditions, as illustrated in Figure 7.1. One, following Italian fascism, emphasizes the ideal of an all-powerful or totalitarian state, in the form of extreme statism. The other, reflected in German Nazism or national socialism, stresses the importance of race and racism (see p. 210).

Figure 7.1 Types of fascism

STATISM

The belief that the state is the most appropriate means of resolving problems and of guaranteeing economic and social development.

RACE

A collection of people who share a common genetic inheritance and are thus distinguished from others by biological factors.

The totalitarian ideal

Totalitarianism (see p. 207) is a controversial concept. The height of its popularity came during the Cold War period, when it was used to draw attention to parallels between fascist and communist regimes, highlighting the brutal features of both. As such, it became a vehicle for expressing anti-communist views and, in particular, hostility towards the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, totalitarianism remains a useful concept for the analysis of fascism. Generic fascism tends towards totalitarianism in at least three respects. First, the extreme collectivism that lies at the heart of fascist ideology, the goal of the creation of ‘fascist man’ – loyal, dedicated and utterly obedient – effectively obliterates the distinction between ‘public’ and ‘private’ existence. The good of the collective body, the nation or the race, is placed firmly before the good of the individual: collective egoism consumes individual egoism. Second, as the fascist leader principle invests the leader with unlimited authority, it violates the liberal idea of a distinction between the state and civil society. An unmediated relationship between the leader and his people implies active participation and total commitment on the part of citizens; in effect, the politicization of the masses. Third, the monistic belief in a single value system, and a single source of truth, places fascism firmly at odds with the notions of pluralism (see p. 290) and civil liberty. However, the idea of an all-powerful state has particular significance for Italian fascism.

The essence of Italian fascism was a form of state worship. In a formula regularly repeated by Mussolini, Giovanni Gentile (see p. 212) proclaimed: ‘Everything for the state; nothing against the state; nothing outside the state.’ The individual’s political obligations are thus absolute and all-encompassing. Nothing less than unquestioning obedience and constant devotion are required of the citizen. This fascist theory of the state has sometimes been associated with the ideas of the German philosopher Hegel (1770–1831). Hegel portrayed the state as an ethical idea, reflecting the altruism and mutual sympathy of its members. In this view, the state is capable of moti-vating and inspiring individuals to act in the common interest, and Hegel thus believed that higher levels of civilization would only be achieved as the state itself developed and expanded. Hegel’s political philosophy therefore amounted to an uncritical reverence for the state, expressed in practice in firm admiration for the autocratic Prussian state of his day.

MONISM

A belief in only one theory or value; monism is reflected politically in enforced obedience to a unitary power and is thus implicitly totalitarian.

POLITICAL IDEOLOGIES IN ACTION . . . The March on Rome

EVENTS: The period 27–29 October 1922 witnessed a political crisis in Italy that brought Mussolini and the Fascist Party to power. Taking advantage of fears of an imminent ‘red’ threat, on 27 October about 26,000 fascist troops started to gather outside Rome, cutting off lines of communication to the capital and preparing for a march on Rome. On 28 October, the king, Victor Emmanuel III, refused Prime Minister Luigi Facta’s call for a decree introducing martial law, despite the fact that regular troops greatly outnumbered fascist forces and were better trained and equipped. The king then summonsed Mussolini to Rome and asked him to form a ministry. The March on Rome duly went ahead on 29 October, celebrating a transfer of power that had, effectively, already taken place. Arriving in Rome by train on the same day, Mussolini took up his appointment and started to form a cabinet.

SIGNIFICANCE: The transfer of power that occurred in Italy in late October 1922 can be said, in important ways, to have occurred within the existing constitutional framework. It did not amount to a seizure of power, as such, and it did not, in itself, alter the distribution of constitutional power. Mussolini’s fascist dictatorship was constructed in the succeeding years. That said, fascist intimidation in October 1922 undoubtedly played a major role in shaping events, but it was a challenge that the Italian state clearly had the ability to resist. The crucial factor in explaining Mussolini’s appointment may therefore be that Victor Emmanuel personally, and Italy’s political, economic and social establishment, more widely, lacked the political will to use this ability, whether this was through panic, weakness or self-interest.

However, despite the complexities and confusions surrounding the events of October 1922, the March on Rome was speedily reinterpreted by fascist historians as a glorious national revolution. The emphasis was placed not on the surrender of the regime, but on the image of Mussolini’s strength, buoyed up by a spontaneous uprising of the Italian people. The March on Rome thus became the founding myth of the Mussolini regime, giving it popular legitimacy and instilling the idea that it had purged a despised parliamentary system. Although regimes of all ideological complexions are prone to rewrite history, the March on Rome perhaps illustrates fascism’s unusual appetite for myth-making, based on an acute awareness of the power of symbolism and emotion.

Totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is an all-encompassing system of political rule that is typically established by pervasive ideological manipulation and open terror and brutality. It differs from autocracy, authoritarianism and traditional dictatorship in that it seeks ‘total power’ through the politicization of every aspect of social and personal existence. Totalitarianism thus implies the outright abolition of civil society: the abolition of ‘the private’. Fascism and communism have sometimes been seen as left- and right-wing forms of totalitarianism, based on their rejection of toleration, pluralism and the open society. However, radical thinkers such as Marcuse (see p. 125) have claimed that liberal democracies also exhibit totalitarian features.

In contrast, the Nazis did not venerate the state as such, but viewed it as a means to an end. Hitler, for instance, described the state as a mere ‘vessel’, implying that creative power derives not from the state but from the race, the German people. Alfred Rosenberg (see p. 213) dismissed the idea of the ‘total state’, describing the state instead as an ‘instrument of the National Socialist Weltanschauung’. However, there is little doubt that the Hitler regime came closer to realizing the totalitarian ideal in practice than did the Mussolini regime. Although it seethed with institutional and personal rivalries, the Nazi state was brutally effective in suppressing political opposition, and succeeded in extending political control over the media, art and culture, education and youth organizations. By comparison, despite its formal commitment to totalitarianism, the Italian state operated, in some ways, like a traditional or personalized dictatorship rather than a totalitarian dictatorship. For example, the Italian monarchy survived throughout the fascist period; many local political leaders, especially in the south, continued in power; and the Catholic Church retained its privileges and independence throughout the fascist period.

Corporatism

Although Italian fascists revered the state, this did not extend to an attempt to col-lectivize economic life. Fascist economic thought was seldom systematic, reflecting the fact that fascists sought to transform human consciousness rather than social structures. Its distinguishing feature was the idea of corporatism, which Mussolini portrayed as the ‘third way’, an alternative to both capitalism and socialism. This was a common theme in fascist thought, also embraced by Mosley in the UK and Perón in Argentina. Corporatism opposes both the free market and central planning: the former leads to the unrestrained pursuit of profit by individuals, while the latter is linked to the divisive idea of class war. In contrast, corporatism is based on the belief that business and labour are bound together in an organic and spiritually unified whole. This holistic vision was based on the assumption that social classes do not conflict with one another, but can work in harmony for the common good or national interest. Such a view was influenced by traditional Catholic social thought, which, in contrast to the Protestant stress on the value of individual hard work, emphasizes that social classes are bound together by duty and mutual obligations.

Corporatism

Corporatism, in its broadest sense, is a means of incorporating organized interests into the processes of government. There are two faces of corporatism. Authoritarian corporatism (closely associated with Fascist Italy) is an ideology and an economic form. As an ideology, it offers an alternative to capitalism and socialism based on holism and group integration. As an economic form, it is characterized by the extension of direct political control over industry and organized labour. Liberal corporatism (‘neocorporatism’ or ‘societal’ corporatism) refers to a tendency found in mature liberal democracies for organized interests to be granted privileged and institutional access to policy formulation. In contrast to its authoritarian variant, liberal corporatism strengthens groups rather than government.

Social harmony between business and labour offers the prospect of both moral and economic regeneration. However, class relations have to be mediated by the state, which is responsible for ensuring that the national interest takes precedence over narrow sectional interests. Twenty-two corporations were set up in Italy in 1927, each representing employers, workers and the government. These corporations were charged with overseeing the development of all the major industries in Italy. The ‘corporate state’ reached its peak in 1939, when a Chamber of Fasces and Corporations was created to replace the Italian parliament. Nevertheless, there was a clear divide between corporatist theory and the reality of economic policy in Fascist Italy. The ‘corporate state’ was little more than an ideological slogan, corporatism in practice amounting, effectively, to an instrument through which the fascist state controlled major economic interests. Working-class organizations were smashed and private businesses were intimidated.

Modernization

The state also exerted a powerful attraction for Mussolini and Italian fascists because they saw it as an agent of modernization. Italy was less industrialized than many of its European neighbours, notably the UK, France and Germany, and many fascists equated national revival with economic modernization. All forms of fascism tend to be backward-looking, highlighting the glories of a lost era of national greatness; in Mussolini’s case, Imperial Rome. However, Italian fascism was also distinctively forward-looking, extolling the virtues of modern technology and industrial life, and looking to construct an advanced industrial society. This tendency within Italian fascism is often linked to the influence of futurism, led by Filippo Marinetti (1876–1944). After 1922, Marinetti and other leading futurists were absorbed into fascism, bringing with them a belief in dynamism, a cult of the machine and a rejection of the past. For Mussolini, the attraction of an all-powerful state was, in part, that it would help Italy break with backward-ness and tradition, and become a future-orientated industrialized country.

FUTURISM

An early twentieth-century movement in the arts that glorified factories, machinery and industrial life generally.

Fascism and racism

Not all forms of fascism involve overt racism, and not all racists are necessarily fascists. Italian fascism, for example, was based primarily on the supremacy of the fascist state over the individual, and on submission to the will of Mussolini. It was therefore a voluntaristic form of fascism, in that, at least in theory, it could embrace all people regardless of race, colour or, indeed, country of birth. When Mussolini passed anti-Semitic laws after 1937, he did so largely to placate Hitler and the Germans, rather than for any ideological purpose. Nevertheless, fascism has often coincided with, and bred from, racist ideas. Indeed, some argue that its emphasis on militant nationalism means that all forms of fascism are either hospitable to racism or harbour implicit or explicit racist doctrines (Griffin, 1993). Nowhere has this link between race and fascism been so evident as in Nazi Germany, where official ideology at times amounted to little more than hysterical, pseudo-scientific anti-Semitism (see p. 211).

VOLUNTARISM

A theory that emphasizes free will and personal commitment, rather than any form of determinism.

The politics of race

The term ‘race’ implies that there are meaningful biological or genetic differences among human beings. While it may be possible to drop one national identity and assume another by a process of ‘naturalization’, it is impossible to change one’s race, determined as it is at birth, indeed before birth, by the racial identity of one’s parents. The symbols of race – skin tone, hair colour, physiognomy and blood – are thus fixed and unchangeable. The use of racial terms and categories became commonplace in the West during the nineteenth century as imperialism brought the predominantly ‘white’ European races into increasingly close contact with the ‘black’, ‘brown’ and ‘yellow’ races of Africa and Asia.

However, racial categories largely reflect cultural stereotypes and enjoy little, if any, scientific foundation. The broadest racial classifications – for example those based on skin colour – white, brown, yellow and so on – are at best misleading and at worst simply arbitrary. More detailed and ambitious racial theories, such as those of the Nazis, simply produced anomalies, one of the most glaring being that Adolf Hitler himself certainly did not fit the racial stereotype of the tall, broad-shouldered, blond-haired, blue-eyed Aryan commonly described in Nazi literature.

Racism

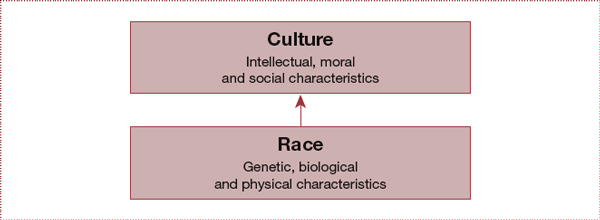

Racism (‘racism’ and ‘racialism’ are now generally treated as synonymous) is, broadly, the belief that political or social conclusions can be drawn from the idea that humankind is divided into biologically distinct races. Racist theories are thus based on two assumptions. The first is that there are fundamental genetic, or species-type, differences among the peoples of the world – racial differences matter. The second is that these genetic divisions are reflected in cultural, intellectual and/or moral differences, making them politically or socially significant. Political racism is manifest in calls for racial segregation (for example, apartheid) and in doctrines of ‘blood’ superiority or inferiority (for example, Aryanism or anti-Semitism). ‘Institutionalized’ racism operates through the norms and values of an institution.

The core assumption of racism is that political and social conclusions can be drawn from the idea that there are innate or fundamental differences between the races of the world. At heart, genetics determines politics: racist political theories can be traced back to biological assumptions, as illustrated in Figure 7.2. A form of implicit racism has been associated with conservative nationalism. This is based on the belief that stable and successful societies must be bound together by a common culture and shared values. For example, Enoch Powell in the UK in the 1960s and Jean-Marie Le Pen in France since the 1980s have argued against ‘non-white’ immigration into their countries on the grounds that the distinctive traditions and culture of the ‘white’ host community would be threatened.

However, more systematic and developed forms of racism are based on explicit assumptions about the nature, capacities and destinies of different racial groups. In many cases, these assumptions have had a religious basis. For example, nineteenth-century European imperialism was justified, in part, by the alleged superiority of the Christian peoples of Europe over the ‘heathen’ peoples of Africa and Asia. Biblical justification was also offered for doctrines of racial segregation preached by the Ku Klux Klan, formed in the USA after the American Civil War, and by the founders of the apartheid system, which operated in South Africa from 1948 until 1993. In Nazi Germany, however, racism was rooted in biological, and therefore quasi-scientific, assumptions. Biologically based racial theories, as opposed to those that are linked to culture or religion, are particularly militant and radical because they make claims about the essential and inescapable nature of a people that are supposedly backed up by the certainty and objectivity of scientific belief.

Figure 7.2 The nature of racism

APARTHEID

(Afrikaans) Literally, ‘apartness’; a system of racial segregation practised in South Africa after 1948.

Nazi race theories

Nazi ideology was fashioned out of a combination of racial anti-Semitism and social Darwinism. Anti-Semitism had been a force in European politics, especially in eastern Europe, since the dawn of the Christian era. Its origins were largely theological: the Jews were responsible for the death of Christ, and in refusing to convert to Christianity they were both denying the divinity of Jesus and endangering their own immortal souls. The association between the Jews and evil was therefore not a creation of the Nazis, but dated back to the Christian Middle Ages, a period when the Jews were first confined in ghettoes and excluded from respectable society. However, anti-Semitism intensified in the late nineteenth century. As nationalism and imperialism spread throughout Europe, Jews were subjected to increasing persecution in many countries. In France, this led to the celebrated Dreyfus affair, 1894–1906; and, in Russia, it was reflected in a series of pogroms carried out against the Jews by the government of Alexander III.

The character of anti-Semitism also changed during the nineteenth century. The growth of a ‘science of race’, which applied pseudo-scientific ideas to social and political issues, led to Jewish people being thought of as a race rather than a religious, economic or cultural group. Thereafter, they were defined inescapably by biological factors such as hair colour, facial characteristics and blood. Anti-Semitism was therefore elaborated into a racial theory, which assigned to the Jewish people a pernicious and degrading racial stereotype. The first attempt to develop a scientific theory of racism was undertaken by Joseph-Arthur Gobineau (see p. 212). Gobineau argued that there is a hierarchy of races, with very different qualities and characteristics. The most developed and creative race is the ‘white peoples’, whose highest element Gobineau referred to as the ‘Aryans’. Jewish people, on the other hand, were thought to be fundamentally uncreative. Unlike the Nazis, however, Gobineau was a pessimistic racist, believing that, by his day, intermarriage had progressed so far that the glorious civilization built by the Aryans had already been corrupted beyond repair.

Key concept

Anti-Semitism

By tradition, Semites are descendants of Shem, son of Noah, and include most of the peoples of the Middle East. Anti-Semitism refers specifically to prejudice against or hatred towards the Jews. In its earliest systematic form, anti-Semitism had a religious character, reflecting the hostility of Christians towards the Jews, based on their complicity in the murder of Jesus and their refusal to acknowledge him as the Son of God. Economic anti-Semitism developed from the Middle Ages onwards, expressing a distaste for the Jews as moneylenders and traders. The nineteenth century saw the birth of racial anti-Semitism in the works of Richard Wagner and H. S. Chamberlain, who condemned the Jewish peoples as fundamentally evil and destructive. Such ideas provided the ideological basis for German Nazism and found their most grotesque expression in the Holocaust.

Joseph Arthur Gobineau (1816–82) A French social theorist, Gobineau is widely viewed as the architect of modern racial theory. In his major work, Essay on the Inequality of the Human Races ([1853–55] 1970), Gobineau advanced a ‘science of history’ in which the strength of civilizations was seen to be determined by their racial composition. In this, ‘white’ people – and particularly the ‘Aryans’ (the Germanic peoples) – were superior to ‘black’, ‘brown’ and ‘yellow’ people, and miscegenation (racial mixing) was viewed as a source of corruption and civilizational decline.

Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) A German philosopher, Nietzsche’s complex and ambitious work stressed the importance of will, especially the ‘will to power’, and influenced anarchism and feminism, as well as fascism. Anticipating modern existentialism, he emphasized that people create their own world and make their own values, expressed in the idea that ‘God is dead’. In Thus Spoke Zarathustra ([1884] 1961), Neitzche emphasized the role of the Übermensch, crudely translated as the ‘supermen’, who alone are unrestrained by conventional morality. His other works include Beyond Good and Evil (1886).

Houston Stewart Chamberlain (1855–1929) A British-born German writer, Chamberlain played a major role in popularizing racial theories, having a major impact on Hitler and the Nazis. In Foundations of the Nineteenth Century ([1899] 1913), largely based on the writings of Gobineau, Chamberlain used the term ‘Aryan race’ to describe almost all the peoples of Europe, but portrayed the ‘Nordic’ or ‘Teutonic’ peoples (by which he meant the Germans) as its supreme element, with the Jewish people being their implacable enemy.

Giovanni Gentile (1875–1944) An Italian idealist philosopher, Gentile was a leading figure in the Fascist government, 1922–9, and is sometimes called the ‘philosopher of fascism’. Strongly influenced by the ideas of Hegel, Gentile advanced a radical critique of individualism, based on an ‘internal’ dialectic in which distinctions between subject and object, and between theory and practice, are transcended. In political terms, this implied the establishment of an all-encompassing state that would abolish the division between public and private life once and for all.

Benito Mussolini (1883–1945) An Italian politician, Mussolini founded the Fascist Party in 1919 and was the leader of Italy from 1922 to 1943. Claiming to be the founder of fascism, Mussolini’s political philosophy drew on the work of Plato, Sorel, Nietzsche and Vilfredo Pareto, and stressed that human existence is only meaningful if it is sustained and determined by the community. This required the construction of a ‘totalitarian’ state, based on the principle that no human or spiritual values exist or have meaning outside the state.

Adolf Hitler (1889–1945) An Austrian-born German politician, Hitler became leader of the Nazi Party (German National Socialist Workers’ Party) in 1921 and was the German leader from 1933 to 1945. Largely expressed in Mein Kampf [My Struggle] (1925), Hitler’s world-view drew expansionist German nationalism, racial anti-Semitism and a belief in relentless struggle together in a theory of history that highlighted the endless battle between the Germans and the Jews. Under Hitler, the Nazis sought German world domination and, after 1941, the wholesale extermination of the Jewish people.

Alfred Rosenberg (1895–1946) A German politician and wartime Nazi leader, Rosenberg was a major intellectual influence on Hitler and the Nazi Party. In The Myth of the Twentieth Century (1930), Rosenberg developed the idea of the ‘race-soul’, arguing that race is the key to a people’s destiny. His hierarchy of racial attributes allowed him to justify both Nazi expansionism (by emphasizing the superiority of the ‘Aryan’ race) and Hitler’s genocidal policies (by portraying Jews as fundamentally ‘degenerate’, along with ‘sub-human’ Slavs, Poles and Czechs).

The doctrine of racial anti-Semitism entered Germany through Gobineau’s writing and took the form of Aryanism, a belief in the biological superiority of the Aryan peoples. These ideas were taken up by the composer Richard Wagner and his UK-born son-in-law, H. S. Chamberlain (see p. 212), whose writings had an enormous impact on Hitler and the Nazis. Chamberlain defined the highest race more narrowly as the ‘Teutons’, clearly understood to mean the German peoples. All cultural development was ascribed to the German way of life, while Jewish people were described as ‘physically, spiritually and morally degenerate’. Chamberlain presented history as a confrontation between the Teutons and the Jews, and therefore prepared the ground for Nazi race theory, which portrayed Jewish people as a universal scapegoat for all of Germany’s misfortunes. The Nazis blamed the Jews for Germany’s defeat in 1918; they were responsible for its humiliation at Versailles; they were behind the financial power of the banks and big business that enslaved the lower middle classes; and their influence was exerted through the working-class movement and the threat of social revolution. In Hitler’s view, the Jews were responsible for an international conspiracy of capitalists and communists, whose prime objective was to weaken and overthrow the German nation.

Nazism, or national socialism, portrayed the world in pseudo-religious, pseudo-scientific terms as a struggle for dominance between the Germans and the Jews, representing, respectively, the forces of ‘good’ and ‘evil’. Hitler himself divided the races of the world into three categories:

•The first, the Aryans, were the Herrenvolk, the ‘master race’; Hitler described the Aryans as the ‘founders of culture’ and literally believed them to be responsible for all creativity, whether in art, music, literature, philosophy or political thought.

•Second, there were the ‘bearers of culture’, peoples who were able to utilize the ideas and inventions of the German people, but were themselves incapable of creativity.

•At the bottom were the Jews, who Hitler described as the ‘destroyers of culture’, pitted in an unending struggle against the noble and creative Aryans.

Hitler’s Manichaean world view was therefore dominated by the idea of conflict between good and evil, reflected in a racial struggle between the Germans and the Jews, a conflict that could only end in either Aryan world domination (and the elimination of the Jews) or the final victory of the Jews (and the destruction of Germany).

MANICHAEANISM

A third-century Persian religion that presented the world in terms of conflict between light and darkness, and good and evil.

This ideology took Hitler and the Nazis in appalling and tragic directions. In the first place, Aryanism, the conviction that the Aryans are a uniquely creative ‘master race’, dictated a policy of expansionism and war. If the Germans are racially superior, other races are biologically relegated to an inferior and subservient position. Nazi ideology therefore dictated an aggressive foreign policy in pursuit of a racial empire and, ultimately, world domination. Second, the Nazis believed that Germany could never be secure so long as its arch-enemies, the Jews, continued to exist. The Jews had to be persecuted, indeed they deserved to be persecuted, because they represented evil. The Nuremburg Laws, passed in 1935, prohibited both marriage and sexual relations between Germans and Jews. After Kristallnacht (‘The Night of Broken Glass’) in 1938, Jewish people were effectively excluded from the economy. However, Nazi race theories drove Hitler from a policy of persecution to one of terror and, eventually, genocide and racial extermination. In 1941, with a world war still to be won, the Nazi regime embarked on what it called the ‘final solution’, an attempt to exterminate the Jewish population of Europe in an unparalleled process of mass murder, which led to the death of some six million Jewish people.

GENOCIDE

The attempt to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnic, racial or religious group.

Peasant ideology

A further difference between the Italian and German brands of fascism is that the latter advanced a distinctively anti-modern philosophy. While Italian fascism was eager to portray itself as a modernizing force and to embrace the benefits of industry and technology, Nazism reviled much of modern civilization as decadent and corrupt. This applied particularly in the case of urbanization and industrialization. In the Nazi view, the Germans are in truth a peasant people, ideally suited to a simple existence lived close to the land and ennobled by physical labour. However, life in overcrowded, stultifying and unhealthy cities had undermined the German spirit and threatened to weaken the racial stock. Such fears were expressed in the ‘Blood and Soil’ ideas of the Nazi Peasant Leader Walter Darré, which blended Nordic racism with rural romanticism to create a peasant philosophy that prefigured many of the ideas of ecologism (discussed in Chapter 9). They also explain why the Nazis extolled the virtues of Kultur, which embodied the folk traditions and craft skills of the German peoples, over the essentially empty products of western civilization. This peasant ideology had important implications for foreign policy. In particular, it helped to fuel expansionist tendencies by strengthening the attraction of Lebensraum. Only through territorial expansion could overcrowded Germany acquire the space to allow its people to resume their proper, peasant existence.

This policy was based on a deep contradiction, however. War and military expansion, even when justified by reference to a peasant ideology, cannot but be pursued through the techniques and processes of a modern industrial society. The central ideological goals of the Nazi regime were conquest and empire, and these dictated the expansion of the industrial base and the development of the technology of warfare. Far from returning the German people to the land, the Hitler period witnessed rapid industrialization and the growth of the large towns and cities so despised by the Nazis. Peasant ideology thus proved to be little more than rhetoric. Militarism also brought about significant cultural shifts. While Nazi art remained fixated with simplistic images of small-town and rural life, propaganda constantly bombarded the German people with images of modern technology, from the Stuka dive-bomber and Panzer tank to the V1 and V2 rockets.

Fascism in a global age

Some commentators have argued that fascism, properly understood, did not survive into the second half of the twentieth century, still less continue into an age shaped by globalization. In the classic analysis by Ernst Nolte (1965), for instance, fascism is seen as a historically specific revolt against modernization, linked to the desire to preserve the cultural and spiritual unity of traditional society. Since this moment in the modernization process has passed, all references to fascism should be made in the past tense. Hitler’s suicide in the Führer bunker in April 1945, as the Soviet Red Army approached the gates of Berlin, may therefore have marked the Götterdämmerung of fascism, its ‘twilight of the gods’. Such interpretations, however, have been far less easy to advance in view of the revival of fascism, or at least of fascist-type movements, in the final decades of the twentieth century and beyond, although these movements have adopted very different strategies and styles.

In some respects, the historical circumstances since the late twentieth century bear out some of the lessons of the inter-war period, namely, that fascism breeds in conditions of crisis, uncertainty and disorder. Steady economic growth and political stability in the early post-1945 period had proved a very effective antidote to the politics of hatred and resentment so often associated with the extreme right. However, uncertainty in the world economy and growing disillusionment with the capacity of established parties to tackle political and social problems have opened up opportunities for right-wing extremism, usually drawing on fears associated with immigration and the weakening of national identity. The end of the Cold War and the advance of globalization have, in some ways, strengthened these factors. The end of communist rule in eastern Europe allowed long-suppressed national rivalries and racial hatreds to re-emerge, giving rise, particularly in the former Yugoslavia, to forms of extreme nationalism that have exhibited fascist-type features. Globalization, for its part, has contributed to the growth of insular, ethnically or racially based forms of nationalism by weakening the nation-state and so undermining civic forms of nationalism. Some, for instance, have drawn parallels between the rise of religious fundamentalism (see p. 188) and the rise of fascism, even seeing militant Islam as a form of ‘Islamo-fascism’.

On the other hand, although far right and anti-immigration groups have taken up themes that are reminiscent of ‘classical’ fascism, the circumstances that have shaped them and the challenges they confront are very different from those found during the post-World War I period. For instance, instead of building on a heritage of European imperialism, the modern far right is operating in a context of post-colonialization. Multiculturalism has also advanced so far in many western societies that the prospect of creating ethnically or racially pure ‘national communities’ appears to be entirely unrealistic. Similarly, traditional class divisions, so influential in shaping the character and success of inter-war fascism, have given way to the more complex and pluralized ‘post-industrial’ social formations. Finally, economic globalization acts as a powerful constraint on the growth of classical fascist movements. So long as global capitalism continues to weaken the significance of national borders, the idea of national rebirth brought about through war, expansionism and autarky will appear to belong, firmly, to a bygone age.

However, what kind of fascism do modern fascist-type parties and groups espouse? While certain, often underground, groups continue to endorse a militant or revolutionary fascism that harks back proudly to Hitler or Mussolini, most of the larger parties and movements claim either to have broken ideologically with their past or deny that they are or ever have been fascist. For want of a better term, the latter can be classified as ‘neofascist’. The principal way in which groups such as the French Front National, the Freedom Party in Austria, the Alleanza Nazionale in Italy and anti-immigration groups in the Netherlands, Belgium and Denmark claim to differ from fascism is in their acceptance of political pluralism and electoral democracy. In other words, ‘democratic fascism’ is fascism divorced from principles such as absolute leadership, totalitarianism and overt racism. In some respects, this ‘de-ideologized’ form of fascism may be well positioned to prosper in a context of globalization. For one thing, in reaching an accommodation with liberal democracy it appears to have buried its past and is no longer tainted with the barbarism of the Hitler and Mussolini period. For another, it still possesses the ability to advance a politics of organic unity and social cohesion in the event of political instability and social dislocation brought about by further, and perhaps deeper, crises in the global capitalist system.

Was fascism merely a product of the specific historical circumstances of the inter-war period?

Was fascism merely a product of the specific historical circumstances of the inter-war period?

Is there such a thing as a ‘fascist minimum’, and if so, what are its features?

Is there such a thing as a ‘fascist minimum’, and if so, what are its features?

How has anti-rationalism shaped fascist ideology?

How has anti-rationalism shaped fascist ideology?

Why do fascists value struggle and war?

Why do fascists value struggle and war?

How can the fascist leader principle be viewed as a form of democracy?

How can the fascist leader principle be viewed as a form of democracy?

Is fascism simply an extreme form of nationalism?

Is fascism simply an extreme form of nationalism?

In what sense is fascism a revolutionary creed?

In what sense is fascism a revolutionary creed?

To what extent can fascism be viewed as a blend of nationalism and socialism?

To what extent can fascism be viewed as a blend of nationalism and socialism?

Why and how is fascism linked to totalitarianism?

Why and how is fascism linked to totalitarianism?

Are all fascists racists, or only some of them?

Are all fascists racists, or only some of them?

Why and how have some fascists objected to capitalism?

Why and how have some fascists objected to capitalism?

To what extent is modern ‘neofascism’ a genuine form of fascism?

To what extent is modern ‘neofascism’ a genuine form of fascism?

Is fascism dead?

Is fascism dead?

FURTHER READING

FURTHER READING

Eatwell, R., Fascism: A History (2003). A thorough, learned and accessible history of fascism that takes ideology to be important; covers both inter-war and postwar fascisms.

Griffin, R. (ed.), International Fascism: Theories, Causes and the New Consensus (1998). A collection of essays that examine contrasting interpretations of fascism but arrive at a ‘state of the art’ theory.

Neocleous, M., Fascism (1997). A short and accessible overview of fascism that situates it within the contradictions of modernity and capitalism.

Passmore, K., Fascism: A Very Short Introduction (2014). A lucid and stimulating introduction to the nature and causes of fascism.