SCAVENGERS AND BIRDS OF PREY

Vultures, Kites, Hawks, Eagles, Harriers, Osprey, Caracaras, and Falcons

87. Turkey Vulture [Turkey Buzzard] i

Cathartes aura [Cathartes atratus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Cathartidae

(Adult calls; Juvenile defensive hiss)

The turkey vulture, often incorrectly called a “buzzard” by country people, soars lazily on the thermals from southernmost Canada to Cape Horn. This large scavenger obviously has been spreading its range northward in recent decades and now occurs north to central New England and Ontario. Audubon, however, had stated unequivocally that it “has never been seen further east than the confines of New Jersey. None, I believe, have been observed in New York.” Although turkey vultures may be extending in the north, they seem to have declined in numbers in the south. Sanitation has eliminated much of their food supply in some cities where garbage dumps and slaughterhouses once offered feeding opportunities. Many are killed along highways as they attempt to feed on animals struck by cars.

Although rather ugly when viewed close at hand on a carcass, turkey vultures are magnificent in the sky. Circling on broad two-toned wings held in a slight dihedral, they soar more and flap less than black vultures. Audubon wrote, “The flight of the turkey-buzzard is graceful compared with that of the black vulture. They are gregarious, feed on all sorts of food and suck the eggs and devour the young of many species of heron and other birds. In the Floridas, I have when shooting, been followed by some of them, to watch the spot where I might deposit my game, which, if not carefully covered, they would devour.”

88. Black Vulture [Black Vulture or Carrion Crow] i

Coragyps atratus [Cathartes atratus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Cathartidae

(Juvenile call; Adult call)

Although this composition may seem too macabre for the living room wall, it is one of Audubon’s best. It is imaginative and well executed. The left-hand bird was a cut and paste job added later.

Black vultures and turkey vultures may sometimes be seen together, but they prefer to associate in assemblies of their own kind. The wide-ranging turkey vulture, found from southern Canada to Cape Horn, is the better sailplane of the two.

The black vulture has a stockier look. It is readily identified by the short square tail that barely projects beyond the broad wings and by the whitish patches toward the wing-tips. Its flight is more labored than that of its redheaded relative—several rapid flaps and a short glide. The black vulture, the one most frequently seen around towns and cities in tropical America, is seldom seen north of southern Pennsylvania and Ohio. It avoids the higher hills and mountains where the turkey vulture often ventures. At a carcass the black vulture is the more aggressive of the two. Both species have declined in numbers in the south in recent years. They are struck by cars at roadside kills and some have succumbed to poisoned carrion. Paradoxically, both slowly seem to be extending their ranges northward. Audubon credited the black vulture with a great power of recollection, recognizing at a great distance the person who had shot at it, and even the horse on which he rode.

89. California Condor [Californian Vulture] i

Gymnogyps californianus [Cathartes Californianus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Cathartidae

(Calls at carcass [captive])

The California condor, now an endangered species numbering only about four dozen, was widespread in Audubon’s time, although he himself never visited the Pacific slope where it was found. His friend, Dr. Townsend, sent him the following account, “The Californian Vulture inhabits the region of the Columbia River to the distance of 500 miles from its mouth and is most abundant in spring at which season it feeds on the dead salmon that are thrown upon the shores in great number. It is often met with near the Indian villages, being attracted by the offal of the fish thrown around the habitations. . . . Their food while on the Columbia is fish almost exclusively, as in the neighborhood of the rapids and falls it is always in abundance. . . . I once saw two near Fort Vancouver feeding on the carcass of a pig that had died. . . . The Californian Vulture cannot, however, be called a plentiful species as even in the situations mentioned it is rare to see more than two or three at a time and these so shy as not to allow an approach to within a hundred yards unless by stratagem.”

Today this very rare vulture, by far the largest bird of prey in the United States, now exists primarily in captivity in zoos in Los Angeles and San Diego where it is under intensive study and propagation with the hope that more may be released in the coast ranges of California.

90. Black-shouldered Kite [Black-winged Hawk]

Elanus caeruleus [Falco Dispar]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

This dainty hawk, graceful as a small gull as it soars and glides aloft, often hovers like a kestrel while pinpointing its prey. It apparently suffered a serious decline early in the present century for reasons that are not clear, but has been making a strong comeback, particularly in Central America and the southwestern parts of the U.S. It is well known to birders who live in California where it often nests in plantings of eucalyptus trees. It has recovered its former numbers in that state and also in southern Texas due, in part, to the efforts of the National Audubon Society and other conservation groups. However, this does not explain its increase throughout Central America, where the widespread planting of eucalyptus trees may have been a contributing factor. Although today it is a rare straggler in Louisiana, Florida, and South Carolina, it must have been more common in the southeast in Audubon’s day, particularly in South Carolina. His drawing was made from a living bird made available to him by Dr. Ravenel of Charleston. He wrote, “The beauty of its large eyes struck me at once and I immediately made a drawing of the bird, which was the first I had ever seen alive.” Later he received a specimen of a female from another friend, Francis Lee, who had procured it on his plantation forty miles west of Charleston.

The black-shouldered kite ranges in open savannah country in South America as far south as Argentina. It is also widespread in Africa and Australia.

91. American Swallow-tailed Kite [Swallow-tailed Hawk] i

Elanoides forficatus [Falco Furcatus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Klee-klee-klee-klee alarm calls)

No bird makes a more memorable impression than this aerialist as it soars over the wooded river swamps of the south, opening and closing its scissor-like tail as it maneuvers in the breeze. Superficially it suggests a giant barn swallow and it flies with swallow-like grace.

It has never been clear why the swallow-tailed kite has declined so drastically since Audubon’s day, when he found it nesting north to Virginia and Kentucky. Subsequently, it was found nesting along the Mississippi River as far north as Minnesota. Today it is limited to the cypress swamps and river lowlands of the southeastern coastal plain through Florida and westward to Louisiana. The flocks of hundreds that Audubon saw in migration are no longer recorded, but the species is still numerous in parts of the tropics from the humid mountains of southern Mexico southward.

Audubon observed, “It is extremely difficult to get near them, as they are generally on the wing through the day and at night rest on the highest pines and cypresses. . . . They always feed on the wing. . . . they soar to immense height pursuing the large insects called Musquito Hawks [dragonflies], and performing the most singular evolutions . . . using their tails with an elegance of motion peculiar to themselves. . . . I never saw one alight on the ground. They secure their prey as they pass closely over it and in so doing sometimes seem to alight particularly when securing a snake.” He depicted the bird in this plate with a garter snake.

Ictinia misisippiensis [Falco Plumbeus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Two-syllable phee-phew call)

The populations of the Mississippi kite, like those of its relatives, the swallow-tailed and white-tailed kites, collapsed around the turn of the century. During the last decade or two, however, this species has recovered markedly and is now rapidly expanding its range northward in the Mississippi Valley and westward throughout the lower Great Plains, taking advantage of the shelter belts planted in the 1930s and 1940s to counteract erosion in the “dust bowl.” The trees in these belts have grown large enough to provide the kind of nesting sites this handsome, gray, falcon-like bird desires. The Mississippi kite now nests north to Missouri, Illinois, and North Carolina. It does not winter in the U.S. but travels by way of the Texas coastal plain, often in considerable flocks, to and from its destination in the tropics.

The Mississippi kite is a graceful, gray hawk with slender, pointed wings and a longish tail. Although falcon-like in shape it is more languid in its manner of flight, flying with swallow-like ease over the southern terrain, the wooded streams, groves, and prairie shelter belts.

Critics have accused Audubon or Audubon’s engraver Havell of copying one of these two birds from a drawing by Alexander Wilson in his American Ornithology, simply reversing or “flopping” the image, a device that commercial artists use to this day when surreptitiously copying other artists.

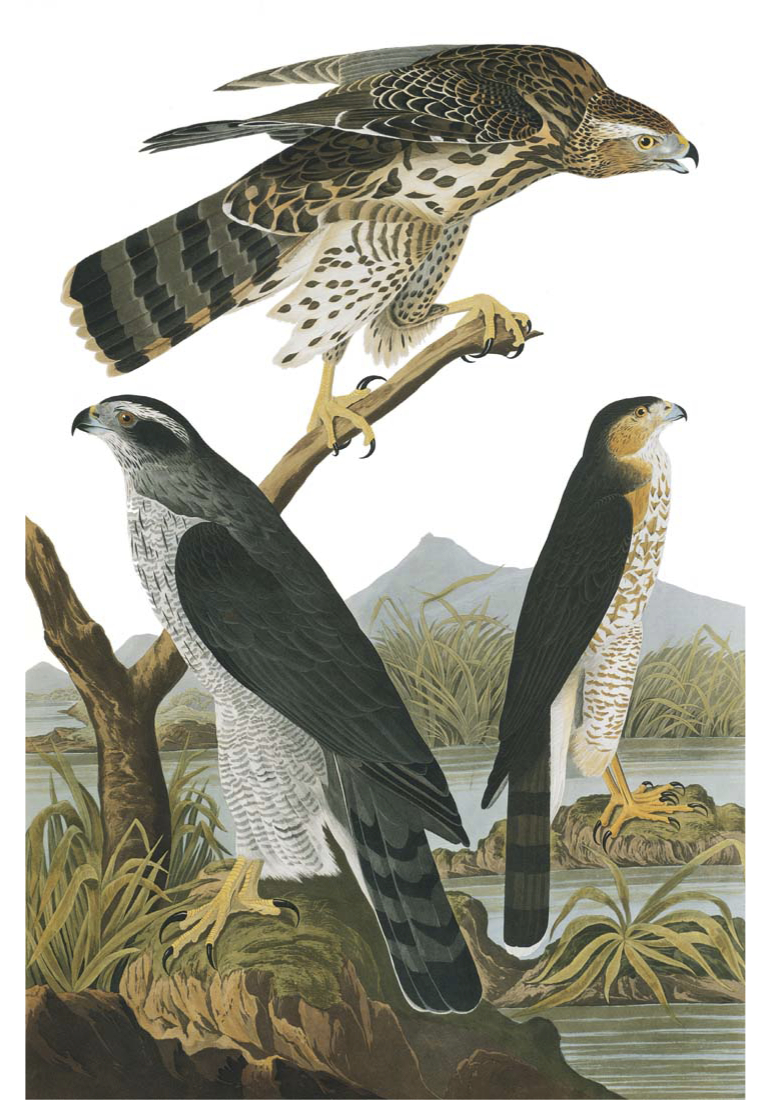

93. Northern Goshawk [Goshawk] i

Accipiter gentilis [Falco Palumbarius]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Alarm call; Wail)

The goshawk is the largest of the three accipiters or true “bird hawks,” long-tailed woodland hawks with relatively short, rounded wings. Like its smaller relatives, the Cooper’s hawk and sharp-shinned hawk, it is adept in dodging through forest growth for its prey, seldom soaring high in the open as the buteos do.

The goshawk is cyclic, dependent on the cycles of its prey in its northwoods environment. When hares or grouse crash, goshawks move south in greater numbers than usual, some penetrating the central U.S. and a few stragglers even reaching the Gulf states. The goshawk had a vastly larger source of food in Audubon’s day when it preyed on passenger pigeons. He wrote, “When the Passenger Pigeons are abundant the Goshawk follows their close masses and subsists upon them. A single hawk suffices to spread the greatest terror among their ranks and the moment he sweeps towards a flock the whole immediately dive into the deepest woods where not withstanding their great speed the marauder succeeds in clutching the fattest. While traveling along the Ohio I observed several hawks of this species in the train of millions of these pigeons.”

This plate was a scissors and paste job combining three different drawings that do not quite jell. The adult goshawk (lower left) and the Cooper’s hawk (lower right) were done in pastel; the immature goshawk (above) was executed in watercolor about twenty years later. In his octavo, Birds of America, Audubon rearranged things yet again and dropped out the Cooper’s hawk.

Accipiter striatus [Falco Velox]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Call; Call; Juvenile call)

The sharp-shin is the smallest of the three accipiters or true “bird hawks,” and Audubon wrote that he never saw one without thinking “there goes the miniature of the goshawk.” It can be identified readily from its somewhat larger relative, the Cooper’s hawk, by the squarish tip of its rather long tail. Sharp-shinned hawks are among the most numerous birds of prey during migration, appearing by the thousands at coastal points such as Cape May, New Jersey, or peninsulas such as Point Pelee, Ontario, or vantage points on the ridges such as Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania. When traveling, a typical mode of flight is several quick beats of the wings and a short glide. Equipped with relatively short, rounded wings, it is able to dart through the branch-work of the forest, surprising its small feathered prey.

The sharp-shinned hawk has a wide range in North America, breeding from coast to coast across the Canadian conifer forests and south to the central parts of the United States. In recent years it has declined or disappeared in many sections south of Canada, possibly due to toxic pesticides in the food chain, but it is still a numerous bird in migration. By winter it withdraws from most of its northern breeding range and can be found as far south as Florida, the Gulf coast, and Mexico.

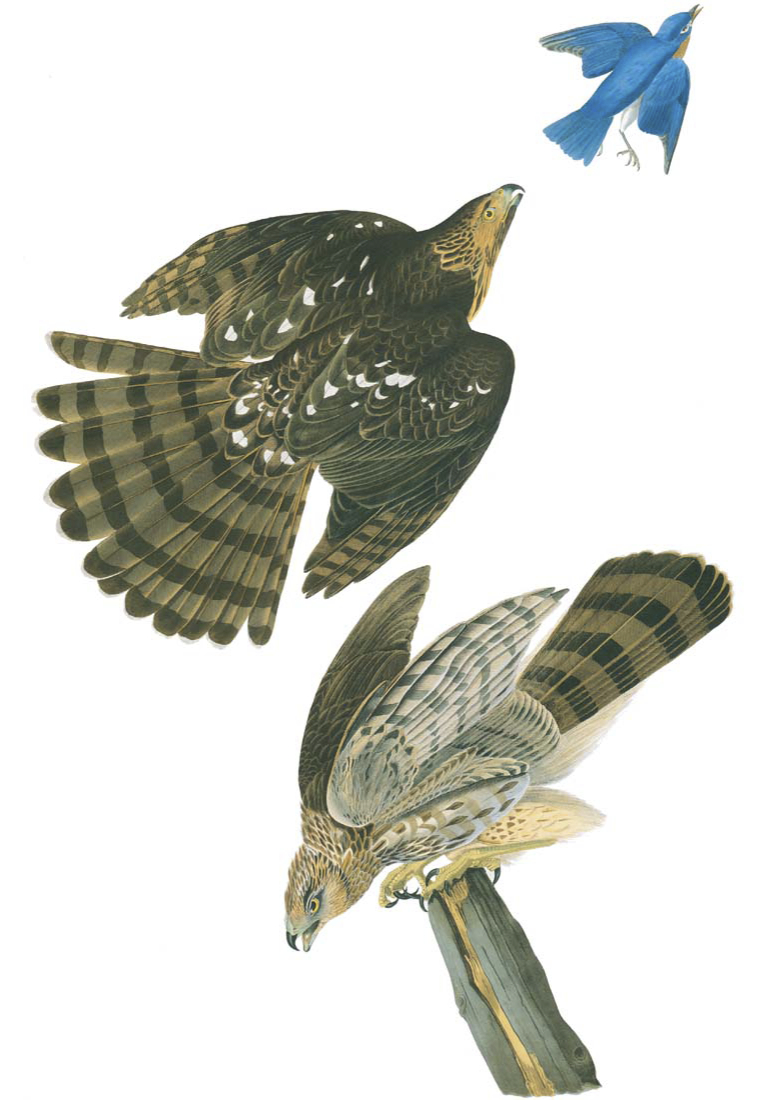

95. Cooper’s Hawk [Stanley Hawk] i

Accipiter cooperii [Astur Stanleii]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

The Cooper’s hawk is almost exclusively addicted to bird killing and, among birds of prey, is the one that can best justify the nickname “chicken hawk,” a name applied indiscriminately by many farmers to any bird of prey, even those that do not attack their fowl.

The Cooper’s hawk, common and widespread in the United States and Canada, suffered a drastic decline in the late 1950s and 1960s, apparently due to ingestion of pesticides such as DDT in their prey. The species was reduced to less than ten percent of its previous numbers in the east. However, the phasing out of chlorinated hydrocarbons has resulted in a good recovery. It seems to have been less affected by pesticides in the western parts of the continent than it had been in the East. The numbers that pass by Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania and other hawk lookouts during migration are now increasing to former numbers. Its relative, the little sharp-shinned hawk, also a bird eater, has fared better, but must be watched.

The Cooper’s hawk, which Audubon called the “Stanley Hawk” on his original plate, was drawn without the bluebird. It was added later by the engraver Havell and is the same figure that is shown on the upper part of the bluebird plate (no. 315).

Buteo jamaicensis [Falco Borealis]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

Audubon observed that once the parents have reared their young, red-tailed hawks form no continuing attachment and they “become as shy towards each other as if they had never met. This is carried to such a singular length, that they are seen to chase and rob each other of their prey, on all occasions.” It was after witnessing such an encounter that Audubon made this drawing “in which you perceive the male to have greatly the advantage over the female, although she still holds the hare firmly in one of her talons even while she is driven towards the earth with her breast upwards.”

As this large, broad-winged, round-tailed hawk swings about in the air and displays its upper surface, it shows the bright rufous tail, an unmistakable field mark. The red-tail is widely distributed on the North American continent, ranging from coast to coast and from Alaska and Canada to Panama. It prefers semi-open country with scattered trees where it can scan the ground for its potential prey. It is one of the few birds of prey that seems to be maintaining its numbers, apparently not being as subject as some of the others to pesticides in the food chain. This is because its diet is primarily rabbits, squirrels, and other rodents that did not ingest the agricultural pesticides that many birds did when DDT was so widely used in the 1960s. The bird-eating hawks, such as the northern harrier, Cooper’s hawk, and peregrine, suffered most.

97. “Harlan’s” Red-tailed Hawk [Black Warrior]

Buteo jamaicensis [Falco Harlani]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

This blackish hawk is now regarded as a variable dark race of the red-tailed hawk. Formerly it was believed to be a distinct species. It differs from the typical red-tailed hawk in not having the distinctive reddish tail, but rather a barred or mottled tail with scarcely a hint of red. Audubon was the first to distinguish “Harlan’s” hawk; he wrote, “Long before I discovered this fine hawk I was anxious to have an opportunity of honoring some new species of the feathered tribe with the name of my excellent friend, Dr. Richard Harlan, of Philadelphia. This I might have done sooner, had I not waited until a species should occur which in its size and importance should bear some proportion to my gratitude toward that learned and accomplished friend.”

The birds that Audubon painted were collected near St. Francisville in Louisiana. He assumed they had bred in the neighborhood, but it is very questionable that they did so because we now know that this form resorts to western Canada and Alaska in the nesting season, and visits Texas and Louisiana only in the winter months. He did state in his account, “Of its nest or eggs nothing is known.” When he shot the male he merely winged it, so he drew it from life. Although he tried to keep it alive, it died within a few days and its preserved skin eventually went to the British Museum. A second bird was collected and drawn in a similar manner.

Buteo lineatus [Falco Lineatus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

The red-shouldered hawk is one of the birds of prey that has declined since Audubon’s day, although it is still numerous enough in Louisiana, where Audubon painted this handsome pair. It has become much less common in the northern states, presumably, although not proved, from the effects of pesticides. This may have had to do with its food preferences, as its close relative, the red-tailed hawk, has maintained its numbers.

Adult birds have rufous shoulders (not always visible as the bird flies overhead) and pale robin-red underparts. When overhead a good mark is a translucent patch or window toward the wing-tip at the base of the primaries. Immatures (plate 99) are streaked below as are most other young hawks. Its call, a two-syllable scream, kee-yar, is distinctive. Although this bird is basically a hawk of the eastern and central parts of the continent, a race of this species is resident in California.

This is one of Audubon’s finer portraits. He knew this pair for three years and saw their nest each spring, placed within a few hundred yards of the spot in which it had been the preceding year. He wrote, “When on several occasions I have had the tree cut down, I have observed the same pair, a few days after, build another nest on a tree not far distant.”

99. Red-shouldered Hawk [Winter Hawk] i

Buteo lineatus [Circus Hyemalis]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

Other ornithologists of the day differed with Audubon about the identity of this bird. They correctly called it the immature of the red-shouldered hawk. Audubon seemed confused on this point. His writings indicate that he considered the “winter hawk” a different species that replaced the red-shouldered hawk in the middle districts during the colder months of the year. He must have changed his mind by the time he published his octavo edition of Birds of America in 1840, because he left this plate out and listed the “winter hawk” or “winter falcon” in his synonomy of the red-shouldered “buzzard.” But by a curious editorial lapse or inconsistency he stated in the first paragraph, “The Red-shouldered Hawk, although dispersed over the greater part of the United States, is rarely observed in the Middle Districts, where, on the contrary, the Winter Falcon usually makes its appearance from the north, at the approach of every autumn, and is of more common occurrence.”

Buteo platypterus [Falco Pennsylvanicus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

The broad-wing alone among the birds of prey is a success story. Audubon, who knew this chunky crow-sized hawk, said it was by no means rare, but he leaves the impression that it was much less numerous than it is now. It is evident that he never witnessed any of the massive migrations of broad-wings that go down the Appalachian ridges about the third week of September. At certain vantage points, such as Mount Tom in Massachusetts, the Kittatinny Ridge in New Jersey, and Hawk Mountain in Pennsylvania, as well as at focal points on the Great Lakes, it is possible in a single day to see thousands of broad-wings soaring in great wheels on the thermals.

This species seems to be prospering because everything about its life style and environment seems to work to its advantage. The second-growth woodlands that it frequents in the northeast have expanded vastly as worked-out farms have been abandoned. Because of its food preferences (no small birds) it has escaped the perils of chlorinated hydrocarbons in the food chain. And it escapes the autumnal barrage of gunfire by making a mass exodus before the hunting season starts. Furthermore, because of deforestation in the tropics (where native hawks have declined) there is more second-growth to hunt over. In Colombia, more than fifty percent of the hawks seen now in winter are broad-wings.

101. Swainson’s Hawk [Common Buzzard] i

Buteo swainsoni [Buteo Vulgaris]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Male scream; Scream)

This buteo of the western plains was unknown to Audubon even though he entered its domain during his travels up the Missouri to the Dakotas, where this bird reaches its eastern limits. The specimen from which he drew the figure was shot by Dr. Townsend near the Columbia River on a rock on which it had its nest. However, Townsend did not supply him with any account of its habits; so Audubon quoted his friend Dr. Richardson, who knew the bird well in the “fur countries” and judged it to be the same species as the common buzzard of Europe. Audubon concurred in this, stating, “When compared with European specimens, mine have the bill somewhat stronger; but in other respects, including the scutella and scales of the feet and toes, and the structure of the wings and tail, the parts are similar.”

Swainson’s hawk is proportioned rather like a red-tailed hawk, but its wings are a bit more pointed. When it glides, as it often does, the wings are held in a dihedral, slightly above the horizontal. The broad breast-band of the adult and the dark flight feathers seen as the bird passes overhead are good field marks; but, inasmuch as this species varies from light-colored birds to very dark ones, identification is not always that easy. Practically all Swainson’s hawks leave North America at the approach of fall and spend the winter on the pampas and plains of Argentina. A few seem to lose their way, ending up in the southern tip of Florida.

102. Rough-legged Hawk [Rough-legged Falcon] i

Buteo lagopus [Falco Lagopus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Alarm screams of pair)

This large buteo or “buzzard hawk” ranges over the Arctic tundra of both the New World and the Old during the summer and migrates to more moderate climes for the long winter. Although it may winter in Nova Scotia and southern Ontario, its main range at that season extends from ocean to ocean across the northern and central states. Because its remote breeding places on the tundra are quite secure, it has not suffered the attrition of habitat of some other birds of prey. When with us it is a bird of the open country, fields, and marshes, where it is readily identified by its habit of hovering on heavily beating wings, osprey-like, while in search of rodents. Typical birds are brown with a blackish belly and a broad black terminal band on the whitish tail. Black wrist marks show on the undersurface of the wings. Some of the birds are dark-bodied but the light ones such as Audubon portrayed in this plate predominate.

Audubon described a habit of this bird not commented on by most bird watchers: “This species is more nocturnal in its habits than any other hawk found in the United States. They alight on trees to roost but appear so hungry or indolent at all times that they seldom retire to rest until after dusk. Their large eyes, indeed, seem to indicate their possession of the faculty of seeing at that late hour. I have frequently put up one that seemed [to be] watching for food at the edge of a ditch long after sunset.”

103. Rough-legged Hawk [Rough-legged Falcon] i

Buteo lagopus [Falco Lagopus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Alarm screams of pair)

Alexander Wilson thought the dark color-phase of the rough-legged hawk was a different species. In his American Ornithology he named it the “Black Hawk, Falco Niger.” Audubon, on the other hand, correctly recognized it simply as a dark plumage of the rough-leg. He regarded the bird in the previous plate as a middle-aged male, and the bird shown here, on the left, as an old male. The figure on the right is of a young bird in its first winter.

The rough-leg exploits an arctic environment during the summer months, hunting for lemmings on the tundra escarpments and along the coasts. Although it breeds locally in Labrador, Audubon and his party failed to find it during their rambles there. On the other hand he knew it well when it came down to the U.S. in winter, exchanging its diet of lemmings for voles and other rodents. He wrote, “The number of meadow mice which this species destroys ought, one might think, to ensure it the protection of every husbandman; but so far is this from being the case, that in America it is shot on all occasions, simply because its presence frightens Mallards and other Ducks, which would alight on the ponds, along the shores of which the wily gunner is concealed; and in England it is caught in traps as well as shot, perhaps for no better reason than because it is a Hawk.”

104. Harris’ Hawk [Louisiana Hawk] i

Parabuteo unicinctus [Buteo Harrisi]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

Harris’ hawk is a common bird of prey from southern Texas and southern Arizona through Central and South America to Argentina, but its appearance elsewhere in the United States is purely accidental. Thus it is curious that Audubon described this species for the first time from a specimen that was taken in Louisiana, where it would be quite accidental. He wrote, “The specimen from which I made my drawing was procured by a gentleman residing in Louisiana who shot it between Bayou Sara and Natchez. It was a female but I have received no information respecting its habits nor can I at present give you the name of the donor however anxious I am to compliment him upon the valuable addition he has made to our fauna by thus enabling me to describe and portray it. I have much pleasure in naming it after my friend Edward Harris, Esq., a gentleman who, independently of the aid which he has on many occasions afforded me in prosecuting my examination of our birds merits this compliment as an enthusiastic ornithologist.”

Although the name “bay-winged hawk” has also been suggested for this species, the name Harris’ hawk persists as the one decided upon by the American Birding Association. This black hawk of the buteo type exhibits a broad white rump and a white band at the tip of its tail and in good light shows bright rufous areas on the thighs and shoulders.

Aquila chrysaetos

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Calls [captive]; Pssa call of immature in flight)

The golden eagle ranges widely throughout the mountainous regions of the Northern Hemisphere, but in North America it breeds principally in Canada and in the western mountains that stretch from Alaska to Mexico. A very few live in the Adirondacks and perhaps elsewhere in the eastern mountains, but their status is not well known. Audubon regarded them as rare; he saw very few during his lifetime, but the one from which he drew this portrait actually came from Vermont where it had been caught in a fox trap. He was tempted to keep it alive, but finally killed it with some difficulty so as to paint its portrait. This took him fourteen days, longer than any other painting except his famed wild turkey. He knew of a pair that bred near the highlands of the Hudson for eight successive years. During the Revolutionary War a company of soldiers was stationed near this nest, and Audubon recounts this story: “A soldier was let down by his companions, suspended by a rope fastened around his body. When he reached the nest he suddenly found himself attacked by the eagle. In self defense he drew his knife and made repeated passes at the bird when accidentally he cut the rope almost off. It began unravelling. Those above hastily drew him up at the moment when he expected to be precipitated to the bottom. So powerful was the effect of the fear the soldier had experienced that ere three days had elapsed his hair became quite gray.”

106. Bald Eagle [Bird of Washington or Great American Sea Eagle] i

Haliaeetus leucocephalus [Falco Washingtoniensis]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

When Audubon first saw the bird that he glorified in this portrait, he believed he had discovered a new species. He wrote, “Not even Herschel, when he discovered the planet which bears his name, could have experienced more rapturous feelings.” He named it “The Bird of Washington” and as his reason explained, “I can only say that as the New World gave me birth and liberty, the great man who insured its independence is next to my heart.” In reality, the bird he described was not new to science. It was merely an immature bald eagle, a species he should have known well. But this young bird puzzled him; it did not look typical. On the other hand, had it been an adult with its white head and white tail he would have recognized it instantly.

Bald eagles prefer fish to all other animal food. They like to be near water, building their huge nests in tall trees locally near the coast and the Great Lakes, where they often become landmarks. More bald eagles nest in Florida than in any other state except Alaska, which has by far the largest population. Protected by federal law and sentiment, our remaining bald eagles have a good chance of surviving if their environment survives attrition and pollution.

107. Bald Eagle [White-headed Eagle] i

Haliaeetus leucocephalus [Falco Leucocephalus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

To quote John James Audubon’s account of the bald eagle in his Ornithological Biography: “The figure of this noble bird is well known throughout the civilized world, emblazoned as it is on our national standard, which waves in the breeze of every clime, bearing in distant lands the remembrance of a great people living in a state of peaceful freedom. May that peaceful freedom last forever!”

Since Audubon penned those brave words the Union has pushed westward to the Pacific. The bald eagle occurs in every state except one—Hawaii. Alaska, the 49th state, can boast many more bald eagles than all the lower 48 states combined. There is also a very strong Canadian population.

Like the ospreys, bald eagles around the Great Lakes and along certain stretches of the Atlantic coast suffered from the effects of DDT and related pollutants, but with the ban on these biocides reproduction is now improving. However, eagles need space, and only in Canada and Alaska do these big birds still find the elbowroom they once knew.

The eagle shown in this portrait was shot in 1820 when Audubon was going down the Mississippi in a flatboat. He painted the bird feeding on a Canada goose, but several years later he replaced the goose with a catfish, more appropriate fare for a bald eagle.

108. Bald Eagle [White-headed Eagle] i

Haliaeetus leucocephalus [Falco Leucocephalus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

Adult bald eagles with their white heads and tails can be recognized instantly, but the dark immatures are less distinctive. They somewhat resemble golden eagles except for the whitish lining of the underwing.

When Audubon painted the aberrant immature bald eagle on plate 106, he was under the mistaken impression that it was a new species, which he named “The Bird of Washington.” He persisted in this belief and included it in the Elephant Folio.

Some ten years after he painted the “Bird of Washington,” Audubon drew another immature eagle, a somewhat older bird that he recognized as a young bald eagle. It is probably two or three years old, already showing much white in the tail. In another year or two it will acquire the distinctive white head and tail of the adult.

In concluding his account of the “White-headed Eagle” Audubon “grieved” that the bald eagle was chosen to be our national bird. He quoted Benjamin Franklin who said in one of his letters, “I wish the Bald Eagle had not been chosen as the representative of our country . . . he is a rank coward: the little King Bird, not bigger than a Sparrow, attacks him boldly, and drives him out of the district, etc., etc.” And yet Audubon, with monumental inconsistency, wrote this of the immature bird: “The Bird of Washington is indisputably the noblest bird of its genus. . . . If America has reason to be proud of her Washington, so has she to be proud of her great Eagle.”

109. Northern Harrier [Marsh Hawk] i

Circus cyaneus [Falco Cyaneus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Male and female alarm calls)

The harrier or “marsh hawk,” white-rumped, slim-bodied, and with proportionately longer wings than most other hawks, has a distinctive way of flying. Its wings are held above the horizontal in a shallow dihedral, much as a turkey vulture flies, as it glides over the fields and marshes looking for likely prey. Unlike most other hawks, it nests on the ground amongst the grass and low bushes, which makes it vulnerable and perhaps explains its disappearance as a breeder over much of its former range in the eastern United States. Audubon claimed that it nested in the “Kentucky barrens” and that he had seen one nest in the pine barrens of Florida and another, found by his son John, on Galveston Island in Texas, localities that are well outside the bird’s known breeding range today.

Many observers have commented on the disproportion between males and females. In some localities, at least, we see many more of the brown females than the gray males. Audubon also noted this: “I have found a greater number of barren females in this species than in any other and to this I in part attribute their predominance over the males.”

Of the various harriers found throughout the world this is the most widespread species, ranging over Europe and Asia as well as North America. It breeds continent-wide across Canada and the northern states and its winter wanderings take some individuals as far south as the northern part of South America.

Pandion haliaetus [Falco Haliaetus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

(Calls; Alarm calls)

Traditionally, the elegant osprey, or “fish hawk,” has escaped the prejudice that condemned most other birds of prey. Since Audubon’s day fishermen and farmers along the coast believed that an osprey’s nest on the property was, like a scarecrow, a warning to “chicken hawks” to keep away. Although there was no basis for this superstition, it served to protect these large vulnerable birds from unnecessary persecution.

It was not until the post-World War II years that the osprey found itself in difficulty. The new wonder chemical DDT and related chemicals were being used widely, and it soon became apparent that there was a connection between their use and the dramatic failure of many eagles, ospreys, and peregrines to produce young. Chlorinated hydrocarbons are slow to break down and are passed along the food chain with a cumulative effect. Poisoned insects are eaten by small fish that are eaten by larger fish that in turn are easily caught by the osprey, which transfers the accumulated poisons to its own tissues.

Although the afflicted ospreys were seldom killed outright by DDT, they laid porous thin-shelled eggs and reproduction dropped to almost nil. Near the mouth of the Connecticut River and elsewhere in the northeast this once abundant nester declined to low levels. Now that chemical pollution is being controlled there is evidence that the surviving ospreys in nearby areas are again having some success in raising normal broods of two or three young.

111. Crested Caracara [Brazilian Caracara Eagle] i

Caracara plancus [Polyborus Vulgaris]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Falconidae

“I was not aware of the existence of the Caracara or Brazilian Eagle in the United States until my visit to the Floridas in the winter of 1831.” So wrote Audubon. After several vain attempts to shoot one he succeeded, and supposing it to be new he sent a detailed description to Dr. Richard Harlan of Philadelphia, requesting him to name the bird (which he did not). In Vol. II of his Ornithological Biography Audubon gave it the name Polyborus Vulgaris. About thirty years later (1865) Cassin renamed the bird after Audubon, and for many years this scavenging bird of prey was known to birders as Audubon’s caracara. Subsequently, after a review of museum material, the differences between the small U.S. populations in Florida and Texas and those farther south were regarded to be merely subspecific and the name Audubon was dropped. The official name is now crested caracara, a species widely distributed in tropical America.

Today the caracara exists very locally in a swath across central Florida, especially in the Kissimmee Prairie, where it seems to be diminishing and is therefore an object of special concern to the National Audubon Society and other conservationists. There are also small scattered populations in southern Texas and southern Arizona. In one form or another caracaras are found all the way south to Tierra del Fuego. Although related to the falcons (in the same family), they are carrion-eating birds that often associate with vultures.

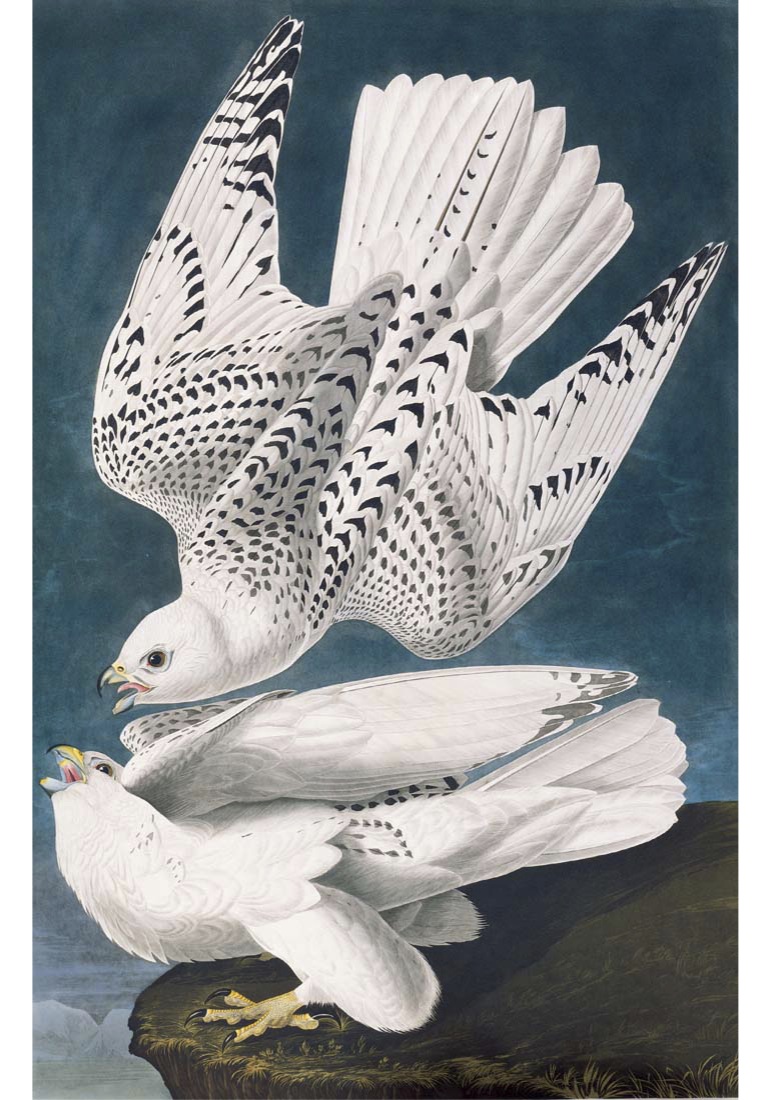

112. Gyrfalcon [Iceland or Jer Falcon] i

Falco rusticolus [Falco Islandicus]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Falconidae

(Wails by pair; Alarm call)

In medieval days when knights and kings rode forth with trained falcons on their wrists, the most valued hawk of all was the gyrfalcon, a prize from the north that could be owned only by those of noblest blood. To say that this bird was worth a king’s ransom would not be far from the truth, for it is recorded that Philip the Bold ransomed his son for twelve white gyrfalcons. After the demands had been made by the captors, it took two years, it is said, to round up the twelve birds. Although gyrfalcons are circumpolar, living in the rocky arctic wastes of Europe, Asia, and North America, most white gyrfalcons come from Greenland, where the sea-roving Vikings obtained them as early as the eleventh century. In fact, Greenland was called “the land of the white falcon.”

The black, gray, and white birds, once supposed to be distinct races, are now regarded as color phases, possible in the same brood of young. The white birds with their arctic camouflage rarely visit the United States; the others are scarce enough, but now and then one is seen along the New England coast in winter. Two feet long, with a spread of about four feet, they can easily overtake and strike down auks, eiders, and other sea birds.

Audubon, who had seen the black gyrfalcon in Labrador, but never a white one, drew the figures in this plate from a bird that had died in captivity.

113. Gyrfalcon [Labrador Jer Falcon] i

Falco rusticolus [Falco Labradora]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Falconidae

(Wails by pair; Alarm call)

This large falcon of the arctic and subarctic regions comes in various color types, black, gray, and white. These are color morphs, not races or subspecies as they were once thought to be. Audubon gave them full specific rank, calling the very dark form the Labrador falcon, the white one (shown in the previous plate) the Greenland falcon. These names, of course, reflect the regions where these two morphs are most frequent, but intermediates or gray ones can be found almost anywhere in the far north.

The two birds shown here were collected in Labrador by Audubon’s son John, when they protested his invasion of their aerie. Audubon drew them the day after their death, sitting up nearly the whole night, his task made no easier by water dripping from the ship’s rigging onto his paper. He complained of his fatigue, which he suspected was due to his age (48 years). “I am no longer young,” he lamented.

Gyrfalcons retreat from the high Arctic in winter, but only rarely go as far south as the Great Lakes or New England. They are larger and more robust than peregrines and somewhat broader-winged, broader-tailed, and more uniformly colored. When they leave the Arctic barrens on their winter wanderings they seek seacoasts and open country.

114. Peregrine Falcon [Great-footed Hawk] i

Falco peregrinus

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Falconidae

(Alarm calls by pair)

The peregrine, the finest and perhaps the fastest bird that flies, was the one used most often in the medieval sport of falconry. Almost worldwide in distribution, it has become an endangered species on the North American continent.

For a long time known as the duck hawk, it disappeared entirely as a breeding species south of Hudson Bay and east of the Rockies. This sudden collapse took place in the late 1950s and early 1960s when it became evident that the several hundred active aeries in eastern North America were no longer producing young. It was discovered that the surviving birds were carrying in their bodies substantial amounts of DDT that in the females inhibited calcification, so necessary for egg production. They laid thin-shelled eggs from which few young hatched.

At Ithaca, New York, in the marvelous hawk barn adjacent to the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology, Dr. Thomas Cade and his associates started to raise young peregrines from the egg, using captive stock from populations that still existed elsewhere in North America. The next step was to take birds raised in this manner and establish them as breeders in suitable places. With all this help the peregrine may again repopulate its former range.

115. Merlin [Le Petit Caporal] i

Falco columbarius [Falco Temerarius]

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Falconidae

When Audubon presented this portrait he was sure that he had a new species, which he called “Le Petit Caporal,” explaining that “The name which I have given to this new and rare species was chosen at the time when Napoleon le Grand was in the zenith of his glory. Everybody knows that his soldiers frequently designated him by the nickname of Le Petit Caporal, which I thought more suitable to our little Hawk than Napoleon or Bonaparte, which I should have adapted, had I been so fortunate as to procure a new Eagle.” The bird was a male merlin, a species already well known in Europe although subspecifically distinct. It was drawn in 1812, but the plate was not engraved until 1829. A year later, in 1830, Audubon presented another plate showing two immature birds of the same species which he called “pigeon hawks,” the name by which this species was known in America for many years until the American Ornithologists’ Union decided to adopt the time-honored British name of merlin.

By the time Audubon published his octavo Birds of America he had sorted things out, and although he did not have much to say about the merlin or “pigeon hawk,” he dropped “Le Petit Caporal.” In the engraving that accompanied the new text he combined the two plates, eliminating one of the two immatures and substituting the adult male from the other drawing.

Falco columbarius

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Falconidae

In his Ornithological Biography Audubon describes a scene on a coastal marsh over which hundreds of gunners are deployed. A merlin appears, stirring a great flock of blackbirds into flight, and by skillful maneuvering cuts one bird from the flock and captures it. While the panic-stricken blackbirds are milling about, Audubon advises: “Now is your time. Pull your trigger and let fly, for it is impossible, should you be ever so inexpert, not to bring down several birds with a shot.” Leaving his comrades to their sport he then returns to the pigeon hawk, which he terms “the little marauder . . . bent on foul deeds.”

In his egocentric fashion, man has long regarded creatures that compete with him as “marauders.” Audubon was no exception. At best, a distinction was made between “good hawks,” meaning those that ate mice, and “bad hawks,” those that ate birds. But today our thinking has changed. We know that the natural predators have lived in a balanced relationship with their prey for eons, and that destroying them will not result in more birds. Other checks, such as disease or starvation, will then act as levelers. Only those who are biologically illiterate still shoot hawks as “vermin.”

The little merlin, formerly called the “pigeon hawk,” is scarcely longer than a robin, and lives in the cool Canadian northwoods. It migrates in open country and along the coast to the southern states, where it spends the winters.

117. American Kestrel [American Sparrow Hawk] i

Falco sparverius

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Falconidae

This beautiful little bird of prey is a falcon, not a true hawk as its obsolete name, sparrow hawk, would imply. Nor does it favor sparrows in its diet. Rather, it seems to prefer mice, grasshoppers, and crickets, which it spots from a high vantage point on some dead tree or telephone wire.

No other diurnal bird of prey except its larger relative the peregrine ranges as widely in the New World. It is found from coast to coast and from northwestern Canada and central Alaska south through the two American continents to Tierra del Fuego. Adaptable, it is impartial to rural roadsides, open country, prairies, deserts, woodland edges, farmlands, and even cities. It escapes persecution, to which the larger birds of prey are subject, by virtue of its size, being hardly larger than a jay. Perched on a wire it looks somewhat like an oversized swallow. Even the slim pointed wings suggest those of a swallow.

Unlike most other day-flying birds of prey, it does not build a nest of sticks in a tree, nor does it lay its eggs on a cliff ledge. It seeks a cavity, usually excavated by a flicker, in some isolated tree or pole. In the desert a woodpecker hole in a saguaro or a hole in a cliff will do. In the western foothills where holes are scarce it may appropriate an old magpie nest. Even a building in the center of a town may offer a nest site.