SONGSTERS AND MIMICS

Dippers, Wrens, Mockingbirds, Thrashers, Thrushes, Gnatcatchers, Kinglets, Pipits, Waxwings, and Shrikes

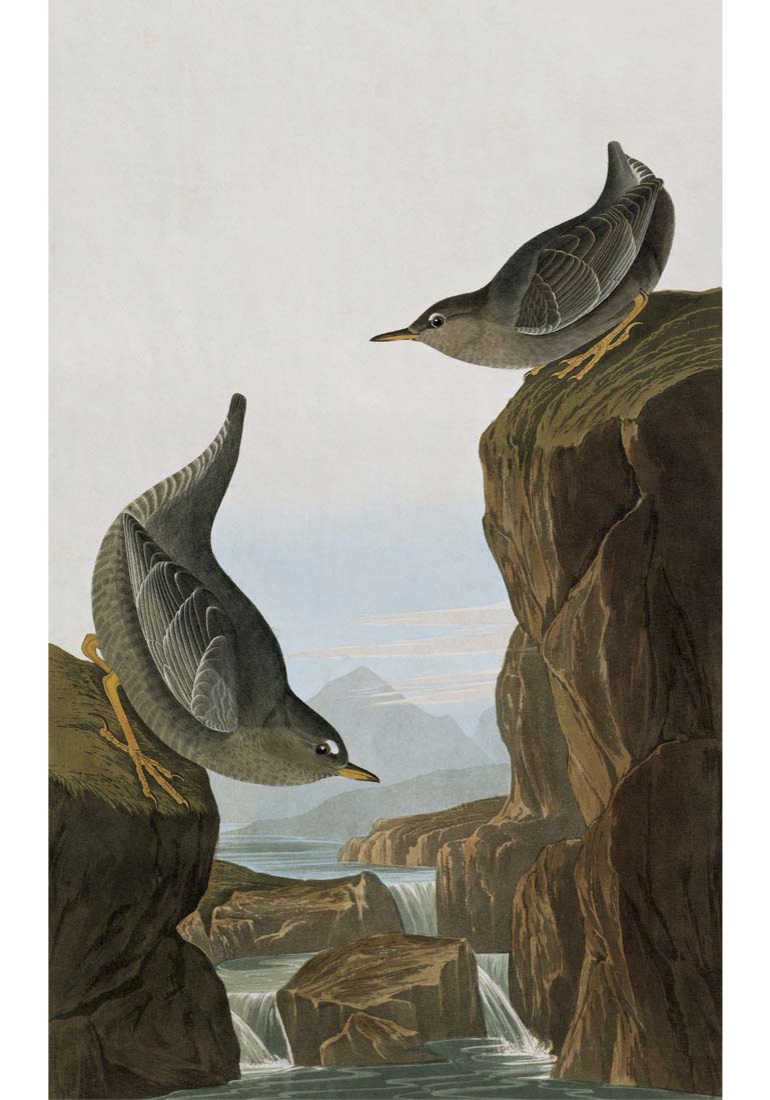

298. North American Dipper [American Water Ouzel] i

Cinclus mexicanus [Cinclus Americanus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Cinclidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon, who had not seen the North American dipper in life, received only a short note about this species from Dr. Townsend, who had collected the specimens in the vicinity of the Columbia River. Having nothing else to go on, Audubon described the habits of the European dipper instead, managing to fill up three pages about that species with material written by his editor, William MacGillivray, who knew the bird well in Scotland.

The American dipper or water ouzel is a chunky slate-colored bird that looks like an oversized wren—heavy-bodied, with a stubby tail that is often held slightly cocked. Like those other stream-loving birds, the spotted sandpiper and the waterthrush, it has the habit of nervously bobbing as it walks along the rocky margins. It prefers the faster-flowing streams in or near the mountains, descending to lower levels in winter. Its unique ability is to plunge into the boisterous maelstrom, where it is able to dive, swim underwater, and actually walk on the bottom in search of aquatic fare. It apparently uses the water pressure in such a way as to keep submerged until it is ready to bob to the surface. Its ringing, wrenlike song, made up of repetitious phrases, can be heard throughout the year. The domed nest, formed of living moss and rootlets, is usually placed on a ledge close to the water, or it may even be fastened to a boulder in midstream.

299. American Dipper [Columbian Water Ouzel and Arctic Water Ouzel] i

Cinclus mexicanus [Cinclus Townsendi and Cinclus Mortoni]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Cinclidae

(Song; Call)

Although there are five kinds of dippers or “water ouzels” in the world, only one is found in North America, where it is confined to the mountain streams in the western parts of the continent from Alaska to Panama. Audubon, however, managed to name two other species which did not exist, apparently misled by immature plumages.

The bird at the left, a female, collected by Captain Brotchie, he named the “Columbian Water Ouzel, Cinclus Townsendi,” in honor of his friend, Dr. Townsend, who sent him so many specimens of unknown birds from the West. The other one, a male, collected by Townsend on the Columbia, he named the “Arctic Water Ouzel, Cinclus Mortoni.”

This was the last plate in Audubon’s Birds of America, but when he came to write his text he realized they were simply young birds and these two “new species” were deleted.

Troglodytes aedon

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Troglodytidae

(Song; Call)

Except for the winter wren, all of the sixty-three kinds of wrens are confined to the New World, and of these only nine cross the Mexican border into the United States. The tropics are saturated with wrens, including such incredible songsters as the nightingale wren and the musician wren. Except for the little winter wren, which has extended its domain across Europe and Asia, the wren with the widest distribution is the familiar house wren, which is found, in one form or another, from Canada to the cool forests of Tierra del Fuego. There is even an outpost population in the Falkland Islands off the southern tip of South America, where in the absence of trees the birds nest in rocky crannies along the beaches.

The stuttering gurgling song of this energetic little bird gives life to the suburban garden. Strategically placed bird boxes, with holes small enough to exclude house sparrows, will attract them near the house, but in the swamps and woodlands their nesting sites are usually in old woodpecker holes or natural cavities. With a touch of humor Audubon has portrayed a family nesting in an old hat. He was puzzled about the bird’s migratory habits and wrote, “The House Wren, if I am not greatly mistaken, passes southward of the United States, to spend the winter.” He was indeed mistaken; it winters commonly throughout the lowlands and the Piedmont of the southern states from Virgina southward but is overlooked easily because it does not sing at that season.

Troglodytes aedon [Troglodytes Americana]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Troglodytidae

(Song; Call)

Here is another of Audubon’s “new species” which did not withstand the test of time. He wrote, “I feel much pleasure in introducing this new species to you, a family which were shot by my sons in a deep wood, eight or ten miles from Eastport in Maine, in the summer of 1832. The young were following their parents through the dark and tangled recesses of their favorite places of abode, busily engaged in search of their insect prey; but their nest was not seen. Some weeks afterwards three adult birds of the same kind were shot near Dennisville in the same district; and on shewing them to my young and intelligent friend, Thomas Lincoln, Esq., he told me that they bred in hollow logs in the woods, and seldom if ever approached the farms. My drawing was made at that place. . . . In winter, while at Charleston, South Carolina, I saw many of them: they had much the same habits as in Maine, remaining in thick hedges along ditches, in the woods, and also not far distant from plantations. I procured several through the assistance of my friend John Bachman, which now form part of my large collection of skins of our birds. The notes of this species differ considerably from those of the House Wren, to which it is nearly allied. I hope to be more familiar with the Wood Wren before my labours are completed.”

Audubon obviously failed to realize that his “Wood Wrens” were really house wrens after all.

Clockwise from top center:

Troglodytes troglodytes [Sylvia Troglodytes]

(Song; Call)

Rock Wren i

Salpinctes obsoletus [Troglodytes Obselata]

(Song; Calls)

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Troglodytidae

The wrens, basically a New World family, number sixty-three species, the majority of which live in the tropics. Only one, the winter wren (or simply the “wren” as it is known in England), made it to the Old World. Being the most northern species, inhabiting the cold forests across Canada and Alaska, it reached Asia via the Aleutian Chain. Once in Asia, it had no other members of its family to compete with and was able to exploit various niches across the vast land mass until it reached the British Isles. An outpost population even found its way to Iceland. In the process of establishing itself more than three-quarters of the way around the globe, it has evolved into a large number of subspecies with slight differences in coloration and song dialect.

Audubon correctly placed the winter wren with the wren of Europe when he first wrote about it. Later, in his octavo edition, he changed his mind and gave it a new specific name, hyemalis (winter); but he conceded, “Still I am not by any means persuaded that they are specifically different.” His instincts were correct and he should have heeded them.

The rock wren, a bird of the western states, was a species Audubon never saw in life. The bird presented here was painted in Charleston from a specimen given to him by Mr. Nuttall and later pasted onto this composition. Havell, the engraver, furnished the twig on which it perches; it should have been shown on a rock.

303. Bewick’s Wren [Bewick’s Long-tailed Wren] i

Thryomanes bewickii [Troglodytes Bewickii]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Troglodytidae

(Song, call [mixed])

(Song, call)

Audubon was the first naturalist to observe and describe this wren, which he collected on the 19th of October, 1821, near St. Francisville in the state of Louisiana. Recognizing it as a new species—larger than the house wren and with much white in its tail—he named it “Bewick’s long-tailed wren” in honor of the English artist-naturalist, Thomas Bewick, “. . . a person too well known for his admirable talents as an engraver on wood, and for his beautiful work on the birds of Great Britain, to need any eulogy of mine.”

Although Audubon failed to note the voice of the Bewick’s wren (pronounced Buick, like the automobile), it does have an agreeable song. It usually starts with high, clear notes followed by lower, burry notes, then ends on a trill. This vocal effort varies in different parts of the bird’s range, which extends from southwestern Canada through the western and middle parts of the United States to Mexico. It is very rarely found east of the Appalachians. Its nest, like that of the house wren or Carolina wren, is usually in a hole or crevice, but it readily will accept a bird box, and for that reason is sometimes erroneously called “house wren.” Like the Carolina wren (and unlike the house wren), Bewick’s wren is largely nonmigratory, wintering throughout most of its range. Lately, there has been an inexplicable decline of this species in much of its range.

304. Carolina Wren [Great Carolina Wren] i

Thryothorus ludovicianus [Troglodytes Ludovicianus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Troglodytidae

(Song, female call [mixed]; Call)

The Carolina wren is one of the typically “southern” birds that has extended its range northward during the last half century, presumably because of the long-term warming trend of the climate. Audubon stated, “A few are seen along the Atlantic shores as far as Pennsylvania, New Jersey and New York. I never observed them farther to the eastward.”

Today the familiar trisyllable song of this large reddish brown wren can be heard as far north as Massachusetts and southern Ontario. Unlike most other wrens they are nonmigratory, and periodically severe winters decimate their ranks. A few usually survive in protected spots—refugia—from which they slowly build back their numbers.

The typical song is a rapid three-syllabled chant that might be interpreted as tea-kettle, tea-kettle, tea-kettle, tea, or chirpity, chirpity, chirpity, chirp. To Audubon it sounded somewhat different. He wrote, “I frequently heard these Wrens singing from the roof of an abandoned flatboat, fastened to the shore a small distance below the city of New Orleans. The little fellow droops its tail and sings with great energy a short ditty somewhat resembling the words come-to-me, come-to-me, repeated several times in quick succession, so loud, and yet so mellow, that it is always agreeable to listen to them.”

Joseph Mason painted this pair of Carolina wrens on a dwarf buckeye.

Cistothorus palustris [Troglodytes Palustris]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Troglodytidae

(Song; Call)

(Song; Call)

This little dweller of the marshes is easily overlooked unless its gurling, rattling song is heard from its hiding place among the reeds. During the summer months it might even be heard singing on still moonlit nights. Audubon noted this habit. He likened its movements in the reeds to those of a mouse and described it as “a homely little bird, seldom noticed unless by the naturalist or by children.”

The marsh wren has a wide summer range in suitable fresh marshes across the northern states and southern Canada. It also breeds locally along the Atlantic and Gulf coasts as well as in the Pacific states. Its nest, a well-woven globular structure with a small entrance hole in the side, is supported by the reeds. Marsh wrens leave the northern states and Canada in the fall and spend the colder season in more temperate southern marshes; however, a very few can be found even in the dead of winter as far north as southern New England, where they would escape notice were it not for a brief chatter at daybreak as they greet the rising sun.

For many years this species was known as the “long-billed marsh wren” to distinguish it from the “short-billed marsh wren,” now officially known as the sedge wren. It can be separated from its lesser relative by the bold white stripe over the eye and the narrow white stripes on its back.

306. Sedge Wren [Nuttall’s Lesser Marsh Wren] i

Cistothorus platensis [Troglodytes Brevirostris]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Troglodytidae

(Song; Call)

The little sedge wren prefers grassy marshes and sedgy meadows, quite unlike the reedy habitat of the marsh wren. It lacks the strongly striped back and broad white eyebrow stripe of its larger and better known relative. Its staccato chattering song is the best clue to its presence.

Nuttall apparently found it quite common in the marshes near Boston a century and a half ago and Audubon named it “Nuttall’s Lesser Marsh Wren.” He wrote, “I hope, kind reader, you will approve of the liberty which I have taken in prefixing the name Nuttall to the present species which was discovered by his indefatigable and enthusiastic devotion to science, in a country where Wilson, Bonaparte, Bachman, Pickering, Cooper, Say, and others had already exerted themselves to the utmost in their endeavors to complete the diversified and interesting fauna.” Actually the species had already been described by a German taxonomist from a specimen originating in “Carolina.” Later in his octavo edition, Audubon changed the appellation to “Short-billed Marsh Wren,” the name which birders used until recently.

This unobstrusive, mouselike little bird is seldom seen today where Nuttall found it, and, inexplicably, it has all but disappeared in the Northeast. The heart of its breeding range in North America remains the upper Midwest and southern Canada. Audubon wrote that he found this small species very abundant in Texas, “where it breeds.” It winters in Texas and he may have thought birds lingering into May were breeders.

307. Northern Mockingbird [Mocking Bird] i

Mimus polyglottos [Turdus Polyglottus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Mimidae

(Song; Call; Call)

Audubon was ecstatic when he wrote, “It is where the great Magnolia shoots up its majestic trunk, crowned with evergreen leaves and decorated with a thousand beautiful flowers that perfume the air around, where the forest and fields are adorned with blossoms of every hue. . . . It is in Louisiana that these bounties of nature are in the greatest perfection. It is there that you should listen to the love song of the Mockingbird. . . . There is probably no bird in the world that possesses all the musical qualifications of this king of song.”

Although some ornithologists might question these superlatives, pointing out that some of the Mexican thrushes are superior, there is no question that the mockingbird is a very versatile vocalist. Not only is it able to mimic many of the other birds that live near it (as well as frogs and crickets), but it also has a large repertoire of its own, and may sing for hours on moonlit nights.

During recent years, probably because of plantings of multiflora roses, mockingbirds have extended their range northward until they are now common in New England and not uncommon in some areas around the Great Lakes. They like the towns and suburbs and are found even about shopping centers and motels.

Audubon portrayed two pairs of mockingbirds defending a nest against a rattlesnake. He was much criticized for this dramatic painting because it was claimed that rattlesnakes do not climb trees.

308. Gray Catbird [Cat Bird] i

Dumetella carolinensis [Turdus Felivox]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Mimidae

(Song; Call)

In this composition Audubon has contrived to display the distinctive rufous undertail coverts of the catbird by cleverly placing the lower bird in a foreshortened position. Some critics would call this distortion, but Audubon was more concerned with showing characteristic points than with purely esthetic considerations.

This dull-colored relative of the brown thrasher and the mockingbird enjoys a wide breeding range, from the Maritime Provinces south to the Carolinas and westward to the Rockies. In winter most catbirds retire to the coastal plain and Piedmont of the southeastern states and some leave the United States entirely for the Central American tropics, but a few may brave cold temperatures as far north as southern New England. It is quite likely that the catbird has extended its range to the north since Audubon’s time, as the mockingbird is now doing. He stated that it was unknown in the state of Maine and in the Maritime Provinces, whereas today it is commonplace there.

The catbird is the special pet of many a gardener, but this was not so a century ago. Audubon wrote, “The boys pelt the poor Thrush [catbird] with stones, and destroy its nest whenever an opportunity presents; the farmer shoots to save a pear; and the gardener to save raspberry; some hate it, not knowing why. . . . Excepting the poor, persecuted Crow, I know no bird more generally despised and tormented than this charming songster.”

309. Brown Thrasher [Ferruginous Thrush] i

Toxostoma rufum [Turdus Rufus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Mimidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon’s dramatic portrayal of the thrashers and the blacksnake reminds one of his controversial painting of the mockingbirds defending their nest against a rattlesnake. The latter painting was much criticized by some of his contemporaries, who averred that rattlesnakes did not climb trees. He was on safer ground when he adopted a similar concept for his painting of the “ferruginous mockingbird,” as he called the thrasher. In this instance he showed a blacksnake, a reptile that does climb trees and which robs nests when it can. However, it is doubtful whether a second pair of thrashers would come to the aid of their distressed neighbors.

In Mexico there are many kinds of thrashers and their allies. Our southwestern states have eight, but in the eastern half of the continent we have only three—the brown thrasher, the mockingbird, and the catbird. Audubon rated the thrasher as the most numerous songbird in the eastern states except for the robin. This certainly would not be true today. It is quite possible that thrashers have declined in the last century, but we lack measurable evidence.

Birds of the thrasher-mockingbird family are often called “mimic thrushes.” Actually, the thrasher and the catbird do not mimic but have their own repertoire of short phrases. Whereas the mockingbird repeats each phrase a half-dozen times or more before going on to the next one, the thrasher repeats but once. This pairing of phrases distinguishes its song from that of the catbird, which does not repeat.

Turdus migratorius

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song, calls [mixed]; Call; Call)

Wherever homesick British colonists settled they named certain birds after the familiar birds of town and countryside back home. Hence, in at least half a dozen different parts of the world we find “robins” simply because they have rusty-red breasts, reminiscent of the “robin redbreast” of England.

In pre-Columbian times American robins were primarily forest birds, but early on they took to the towns and shade trees. Undoubtedly, the manicured lawns, where earthworms were easier to come by, were partly responsible for this adoption of a new habitat.

But in Audubon’s time robins did not enjoy the security that they know today. He writes of the winter sojourn of robins in the South: “Their presence is productive of a sort of jubilee among the gunners, and the havoc made among them with bows and arrows, blowpipes, guns, and traps of different sorts, is wonderful. . . . Every gunner brings them home by the bagful.”

It was the destruction of robins, as much as anything else, that sparked the Audubon movement in the early years of this century. Today it would be unthinkable to shoot a robin; it is perhaps America’s most beloved bird, the symbol of spring to winter-weary Northerners. It is free to walk our lawns with no fear except for the neighborhood cats.

From top to bottom:

311. Sage Thrasher [Mountain Mocking Bird] i

Oreoscoptes montanus [Orpheus Montanus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Mimidae

(Song; Call)

Varied Thrush i

Ixoreus naevius [Turdus Naevius]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Calls)

The sage thrasher, perched at the top, was called the mountain mockingbird by early ornithologists. Audubon never made the acquaintance of this resident of the sagebrush, mesas, and deserts of the West, and the specimen shown here was procured in the Rockies by Dr. Townsend, who sent it to Philadelphia where Audubon made the drawing. It was the first time this species had been figured.

The other two birds are varied thrushes, otherwise known as “Alaska robins.” Audubon quotes Dr. Richardson: “This species was discovered at Nootka Sound in Captain Cook’s third voyage. . . . Male and female specimens in the possession of Sir Joseph Banks were described by Latham. . . . The specimens represented in this work were procured at Fort Franklin in the spring of 1826.” Later, Dr. Townsend and Mr. Nuttall found it abundant on the western slope of the Rockies.

In general appearance the varied thrush resembles a robin, but with an orange eyebrow stripe, orange wing-bars, and a black band across the chest. Although a bird of the humid Northwest, wintering in the Pacific states, recently it has been turning up in the East as an occasional visitor. There are now many winter records, mostly at feeders, from maritime Canada to the southeastern states.

Hylocichla mustelina [Turdus Mustelinus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

“You now see before you my greatest favorite of the feathered tribes of our woods,” wrote Audubon. “How often it has revived my drooping spirits, when I have listened to its wild notes in the forest, after passing a restless night in my slender shed, so feebly secured against violence of the storm, as to show me the futility of my best efforts to rekindle my little fire. . . . How fervently have I blessed the Being who formed the Wood Thrush, and placed it in these solitary forests.”

This species, one of five spotted brown thrushes native to North America, is the best known because it summers throughout most of the United States east of the plains, and also in southeastern Canada, singing its vesper strains within the hearing of many suburban homes and country dwellings. Even those who know its song well may seldom see the singer, because it hides in the shadows where its brown coloration matches the leafy woodland floor. It may be identified readily among the other thrushes by the deepening redness about the head and the larger, more numerous round spots on its breast. The wood thrush leaves the United States in fall to spend the winter in Central America.

It is difficult to believe that at one time people in our country actually ate wood thrushes, but Audubon wrote, “Their flesh is extremely delicate and juicy, and many of them are killed with the blowgun.”

Catharus guttatus [Turdus Minor]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

If a consensus were taken among bird watchers as to which North American bird had the most beautiful song, the vote would probably go to the hermit thrush, whose flute-like strains have such a haunting quality in the summer sprucewoods of New England and Canada. Again we question Audubon’s ear when we read, “Its song is sometimes agreeable.” He speaks of it as a “constant resident in the southern states” and says that “this thrush prefers the darkest, most swampy, and most secluded canebreaks along the margins of the Mississippi where it breeds and spends the summer.” Puzzling words, indeed, considering that the hermit thrush is definitely a bird of the Canadian zone, breeding southward only at the higher altitudes in the Appalachians and the Rockies. Inasmuch as the several brown thrushes of eastern North America are so similar, it is likely that he mixed some of his observations of the hermit thrush with those of the wood thrush.

The hermit thrush is distinguished easily from the other brown thrushes by its reddish tail, whereas the wood thrush is redder about the head and the veery is of a uniform, warm color above. When discovered among the leafy undergrowth, the hermit thrush may stand rather erect with an occasional jerk or lift of its tail. Hardier than the other brown thrushes, it does not migrate deep into the tropics as they do, but remains in the southern half of the United States during the colder months. In winter, a few can be found coastally as far north as southern New England.

Catharus fuscescens [Turdus Wilsoni]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Calls)

The song or the veery, liquid and ethereal, wheels downward, evoking images of deep deciduous woods and ferny dells. The uniform tawny brown upper parts of the bird and the relatively sparse spotting on its chest are the best clues by which it may be separated from the other brown thrushes.

The veery, formerly called the Wilson’s thrush, summers from the Maritimes and the northeastern states westward through the Great Lakes region to the Rockies. It also extends southward through the higher Appalachians to northernmost Georgia. Birds elsewhere in the southern states see it only as a migrant because it winters far to the south in Central America and northern South America. Audubon drew this bird in Maine, placing it on the ground near a fringed orchis and a clump of bunchberries.

Of its nesting, Audubon wrote, “The Tawny Thrush . . . seeks refuge in the concealment of dark shady woods, near brooks or moist grounds. There, in a low bush, or on the ground beneath it, this bird builds its nest, which is large, composed externally of dry leaves, mosses, and the stalks of grasses, and lined with finer grasses, and delicate fibrous portions of different kinds of mosses, without any mud or clay. The eggs, which are deposited early in June, are from four to six, and resemble those of the Catbird in colour and shape, but are of smaller size.”

315. Eastern Bluebird [Blue-bird] i

Sialia sialis [Sylvia Sialis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

This gentle bird, scarcely larger than a sparrow, reminded Audubon of the “Robin redbreast” of Europe, because of a superficial similarity of appearance and habits. Both are small members of the thrush family, so the comparison is not far-fetched. Indeed, the first settlers of Massachusetts called it the “Blue Robin.”

The eastern bluebird spreads over an extensive range, from the Gulf of St. Lawrence and James Bay south to Nicaragua and west to the Rockies. The very similar western bluebird replaces it from there to the Pacific.

In recent decades the bluebird has fallen on hard times in the northern states, for a number of reasons. The spread of the starling, which usurps its nesting sites, has had an adverse effect. Even tree swallows, more pugnacious than bluebirds, offer stiff competition for boxes and other nesting places. The spraying of orchards with chemicals has made life particularly difficult. Added to all these woes have been several hard winters in the central and southern states which have periodically decimated them. To escape the cold, many bluebirds took refuge in the little chimneys of tobacco curing sheds and were asphyxiated. It is estimated that several million died in this manner.

Bluebird clubs and bluebird trails have been organized to help these beleaguered birds by putting up boxes. Everyone loves the bluebird and wants to help because it is a traditional symbol of happiness and a harbinger of spring.

Clockwise from top center:

Dendroica townsendi [Sylvia Townsendi]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Type 1 song; Type 2 song; Chip call)

Mountain Bluebird [Arctic Blue Bird] i

Sialia currucoides [Sialia Arctica]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

Western Bluebird [Western Blue Bird] i

Sialia mexicana [Sialia Occidentalis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

A western trio. The Townsend’s warbler (upper left), a summer resident of the cool fir forests of northwestern North America, was collected by Nuttall on the Columbia River and was named in honor of his companion, Dr. Townsend. It was a male, apparently a migrant en route to more northerly spots in Canada or Alaska.

The mountain bluebird (male at upper right, female in center), called the “Arctic Blue Bird” by Audubon, is more northerly or montane in its distribution than the western bluebird (next species) but sometimes associates with it in winter. Audubon wrote that this beautiful species was introduced to the notice of ornithologists by Dr. Richardson. The specimens and those of the other species shown on this plate were collected by Dr. Townsend. The female mountain bluebird had not been figured previously.

The two birds shown at the bottom are western bluebirds (male, right; female, left). They closely resemble the eastern bluebird (plate 315) but can be recognized by the blue throat of the male and the rusty back. This species was first discovered by Dr. Townsend, who described it and sent specimens to Audubon for this drawing. Nuttall furnished the material for the text, commenting that the “song is more varied, sweet and tender than that of the common Sialia, and very different in many of its expressions.”

From top to bottom:

317. Hermit Thrush [Little Tawny Thrush] i

Catharus guttatus [Turdus Minor]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

Townsend’s Solitaire [Townsend’s Ptilogonys] i

Myadestes townsendi [Ptilogonis Townsendi]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

Gray Jay [Canada Jay] i

Perisoreus canadensis [Corvus Canadensis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

Audubon described the thrush at the top as a new species, which in his large work he called the “Little Tawny Thrush, Turdus Minor.” Later, in his octavo, he changed it to “Dwarf Thrush, Turdus Nanus.” Since then it has been relegated to subspecific status, as simply a small race of the well-known hermit thrush. The drawing was made in London from specimens sent to him by Dr. Townsend who collected them in the Northwest.

The Townsend’s solitaire (center), a wilderness-loving thrush which Audubon called “Townsend’s Ptilogonys,” was indeed a new species when he painted it. He wrote, “The only individual of this species that I have ever seen is a female, which was shot near the Columbia River, and kindly transmitted to me by my friend Mr. Townsend, after whom, not finding any description of it, I have named it.”

The lower figure, the large dusky bird with the white whisker stripe, is a young gray (or Canada) jay. Unlike the young of other jays, the juvenal looks entirely different from its parents (see plate 281), prompting Audubon to write about this drawing: “I was induced to give the young of the Canada Jay simply because my friend, Mr. Swainson, formed of it a new species under the name of Garrulus Brachyrhynchus” (or “Short-billed Jay”).

318. Blue-gray Gnatcatcher [Blue-grey Flycatcher] i

Polioptila caerulea [Sylvia Coerula]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

This slender mite, smaller than a chickadee, blue-gray above and whitish below, with a long black and white tail, suggests a miniature mockingbird. However, it has no comparable song and gives voice only to a thin, wheezy series which fails to attract as much attention as its note, a peevish zpee or cheee.

Although the gnatcatcher ranges from Ontario to Guatemala, only in recent years has it become commonplace in New England, arriving in late April when the trees are still bare. It soon constructs a very neat little cup of plant down, oak catkins, and spider webs, saddling it to a small limb or fork and decorating it externally with lichens so that it appears to be a knob or excrescence on the limb itself. In spite of this camouflage the nest is often discovered by crows, which rob it of its eggs. The gnatcatchers usually tear up the old nest and start a new one nearby, using the same materials. After one or two false starts, the forest is leafy enough to afford camouflaged protection.

Audubon apparently did not have much to say about this unobstrusive little bird, so to fill up space he wrote at length about the black walnut tree, twigs of which were drawn as a setting for the birds shown here.

319. Golden-crowned Kinglet [Golden-crested Wren] i

Regulus satrapa [Regulus Cristatus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

The kinglets, related to the Old World warblers, are tiny mites, smaller, chubbier, and shorter-tailed than our wood warblers. They have the habit of nervously flicking their heavily barred wings. The golden-crowned kinglet, with its heavily striped crown, is easily separated in any plumage from the ruby-crown which lacks such head striping. The female has a yellow crown, the male orange.

This little kinglet lisps its sibilant see-see-see in the cold boreal forests that stretch across Canada. It seems to be extending its range in spruce and Norway pine plantations in the Northeast and a few nest in the higher Appalachians as far south as the Great Smokies in North Carolina. In the western mountains it breeds all the way from southern Alaska to the high mountains of Guatemala. During winter, most kinglets desert the more northern fir forests and spread widely over the United States. During exceptionally harsh winters their population may be decimated.

Audubon’s assistant, George Lehman, drew the plant, powdery thalia, Thalia dealbata, an uncommon species found in South Carolina and elsewhere in the southeastern states. It is perennial and flowers in August and September before golden-crowned kinglets arrive from the North. Audubon defended his inclusion of such an inappropriate plant, “. . . which I thought might prove agreeable to your eye.”

320. Ruby-crowned Kinglet [Ruby-crowned Wren] i

Regulus calendula

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

(Song; Call)

The bright ruby crown patch of this kinglet is concealed much of the time, and shows mostly when the bird is animated or excited. Only the male has it, but both sexes can be distinguished from the golden-crowned kinglet by the lack of head striping. Instead there is a conspicious broken white eye-ring. Both species have strong wing-bars and flick their wings nervously as they forage about. The plant shown in the composition is sheep laurel, an appropriate setting for the birds because it is a shrub common to their habitat.

Audubon, who undoubtedly knew this bird well in migration and in winter, apparently had never heard one in full song until he visited Labrador in 1833, when “the notes of a warbler came on my ear, and I listened with delight to the harmonious sounds that filled the air around, and which I judged to belong to a species not yet known to me. The next instant I observed a small bird perched on the top of a fir tree, and on approaching it, recognized it as the vocalist that had so suddenly charmed my ear and raised my expectations.” His son John raised his gun and brought down the bird which he was surprised to find, when it was finally retrieved from where it had fallen, to be this familiar species. Although kinglets do sing in migration, they are in full voice when they reach home. The song is surprisingly forceful for so small a bird.

321. “Cuvier’s Kinglet” [Cuvier’s Wren]

“Regulus Cuvieri”

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Muscicapidae

This is another of Audubon’s mystery birds. He wrote, “I have named this pretty and rare species after Baron Cuvier. . . . I shot the bird represented in the plate, on my father-in-law’s plantation of Fatland Ford, on the Schuylkill River in Pennsylvania, on the 8th of June, 1812, while on a visit to my honored relative, Mr. William Bakewell. The drawing which I then made I kept for a long time without describing the bird from which it was taken. I killed this little bird, supposing it to be one of its relatives, the Ruby-crowned Kinglet, while it was searching for insects and larvae amongst the leaves and blossoms of the Kalmia latifolia, on a branch of which you see it represented, and was not aware of its being a different bird until I picked it up from the ground. I have not seen another since, nor have I been able to learn that this species has been observed by any other individual. It might, however, be very easily mistaken for the Ruby-crowned Kinglet, the manners of which appear to be much the same.”

The A.O.U. Checklist stated that the published colorplate may have been based to some extent on memory. No similar bird has ever been seen since. It could have been an aberrant ruby-crowned kinglet or possibly a hybrid between the ruby-crowned and golden-crowned kinglets. However, the date itself is unusual—June 8—a time when kinglets of any sort should be farther north or in the mountains.

322. American Pipit [Brown Titlark] i

Anthus rubescens [Anthus Aquaticus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Motacillidae

(Song; Calls; Call)

When Audubon painted this drab little bird of the beaches, fields, and barren lands, he simply called it the “Brown Lark.” Later he changed it to “Titlark” or “Pipit.” While on a trip from France, when his ship was off the Grand Banks near Newfoundland, several pipits came aboard, and were so hungry that they eagerly ate the crumbs he threw to them. He correctly recognized the bird that he painted as being similar to the species that lived in Europe.

The American pipit, the name it goes by today, has a wide distribution throughout the colder parts of our hemisphere, ranging from the tundras of Canada and Alaska in the summer to the beaches of Central America in the winter. In the Old World a similar species, the water pipit, has an even wider domain, traveling from the shores of the Arctic Ocean to southern Asia and northern Africa.

This slender, brown, lark-like bird, about the size of a sparrow, has a habit of bobbing or wagging its tail, a quick clue to its identification. Its note, a thin jeet or jee-eet, is distinctive. When it flies, the outer tail feathers flash white, reminding one of a vesper sparrow or a junco. Unlike those finches it has a thin bill, walks instead of hops, and vibrates its tail constantly.

323. American Pipit [Prairie Titlark] i

Anthus rubescens [Anthus Hypogaeus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Motacillidae

(Song; Calls; Call)

When Audubon drew this bird in pencil, pastel, and watercolor in 1815, he was under the impression he was dealing with a new species, and he presented it as such in the Elephant Folio. Later, in his octavo edition, he apparently decided it was only an immature example of the familiar American pipit (see previous plate).

Pipits, at best, are a confusing group of similar brown birds, especially in Alaska and the Aleutians where stray species from Asia are sometimes recorded. In eastern North America we have only two, the widespread American pipit and the Sprague’s pipit, which apparently Audubon never knew until he embarked on his Missouri River adventure in 1843, after completing the exhausting work on his Elephant Folio. At Fort Union he found the Sprague’s pipit abundant, and named it after his companion, Isaac Sprague, who shot the first one.

One of the field marks of the American pipit, a bird of the open country, is the presence of white outer tail feathers, a feature that seems absent in this drawing of the “Prairie Titlark,” as Audubon called it. American pipits undergo quite a plumage change between summer and winter. Breeding birds on the Arctic tundra are much grayer above and warmer on the breast than birds on their wintering grounds in the southern United States.

324. Bohemian Waxwing [Bohemian Chatterer] i

Bombycilla garrulus [Bombycilla Garrula]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Bombycillidae

The sleek waxwings, with their pointed crests, yellow tailtips, and waxy red droplets on their secondaries, are among the most elegant of birds. The cedar waxwing (next species) is well known throughout the United States and much of Canada. The Bohemian waxwing, or “Bohemian Chatterer,” as Audubon called it, is not. It breeds in the wilder northwestern part of the continent, from central Alaska and western Canada to Hudson Bay. In winter, however, there is often an eastward movement to the Maritime Provinces and northern New England. A few individuals might even be seen with cedar waxwings as far south as the Great Lakes, where they can be separated from the “cedarbirds” by their larger size, grayer color, and rusty red, instead of white, undertail coverts. Audubon never saw this species, but his sons, while rambling near Boston in the autumn of 1832, saw a pair which they pursued for an hour without success.

Audubon wrote, “The specimens from which I made the figures of the male and female represented in the plate were given to me by my friend Thomas McCulloch of Pictou in Nova Scotia.” McCulloch wrote, “They could be shot at almost any hour of the day in the streets of Pictou.”

325. Cedar Waxwing [Cedar Bird] i

Bombycilla cedrorum [Bombycilla Carolinensis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Bombycillidae

No bird is sleeker than a waxwing. Its black mask, surmounted by a pointed crest, and the yellow band across the tip of the tail are unmistakable field marks (see also Bohemian waxwing on the previous plate). Widespread in the forested regions of Canada and the northern United States, the waxwing may spend the winter there if the berry crop is good, or it may wander as far south as Mexico or even Panama if the food supply is exhausted. Like the goldfinch, it waits until summer is well advanced before it settles down to the serious business of nesting and reproducing its kind. This may be because its preferred food—berries and other wild fruits—does not ripen earlier in the season.

No birds are more gregarious or gluttonous if they discover a bonanza of berry-laden bushes. Audubon wrote, “The holly, the vines, the persimmon, the pride of China, and various other trees, supply them with plenty of berries and fruits on which they fatten, and become so tender and juicy as to be sought by every epicure for the table. I have known of an instance of a basketful of these little birds having been forwarded to New Orleans as a Christmas present. The donor, however, was disappointed in his desire to please his friend in that city, for it was afterwards discovered that the steward of the steamer, in which they were shipped, made pies of them for the benefit of the passengers.”

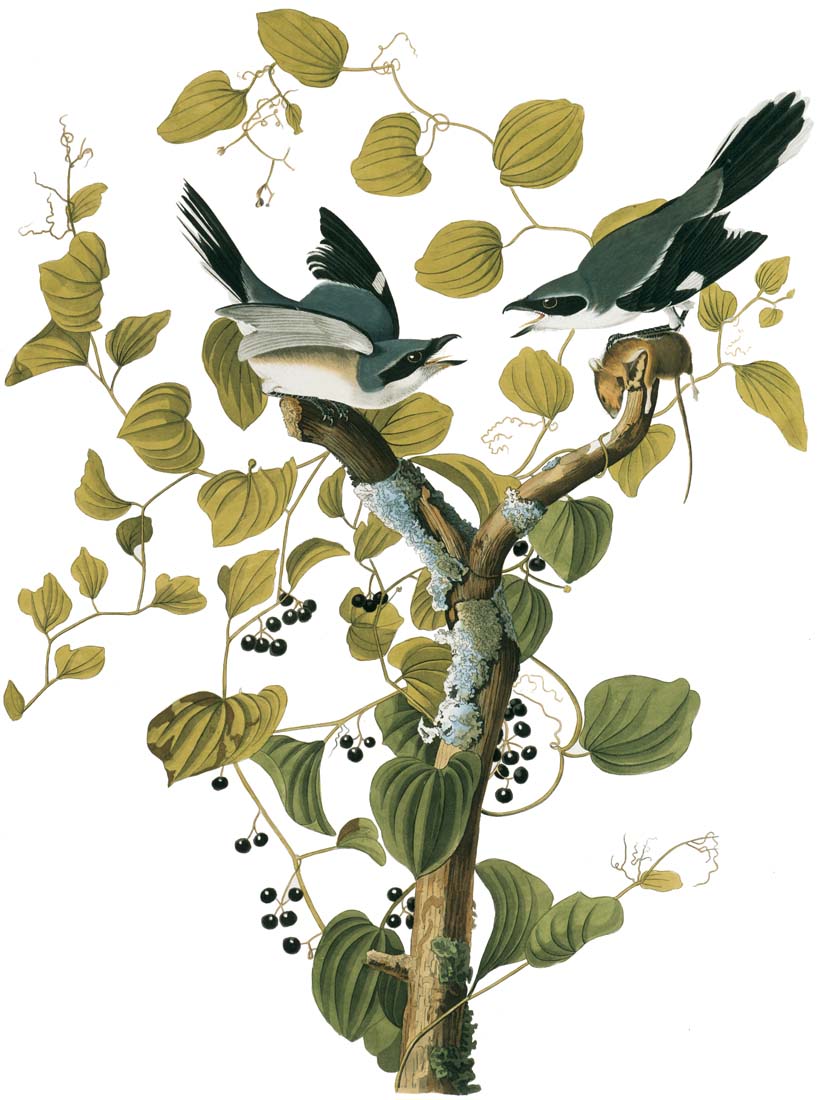

326. Northern Shrike [Great American Shrike or Butcher Bird] i

Lanius excubitor [Lanius Septentrionalis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Laniidae

(Song; Juvenile call; Call, song)

Audubon seemed to make no clear distinction between this species and the loggerhead shrike. Such statements as “this species spends the greater part of the year in our most eastern states,” and “many individuals remain in the mountainous districts of the middle states and breed there,” are quite erroneous. Unlike the loggerhead shrike, which is resident throughout much of the United States, the northern shrike is confined in the summertime to a relatively narrow belt in Canada and Alaska where the stunted boreal forest gives way to tundra. It is also found widely in Eurasia.

During the winter months the northern shrike may remain fairly far north or it may wander sporadically as far south as the middle states. Like the loggerhead shrike it prefers semi-open country with lookout posts or telegraph wires from which to scan the area for mice or small birds, which it impales on twigs, thorns, or barbed wire.

We need not take Audubon to task too severely for confusing the two shrikes. Most field birders find it quite difficult to be certain about the identity of some of the shrikes they see. In general, northern shrikes are paler, with a suggestion of fine barring on the underparts; immature birds are browner. The base of the lower mandible is pale in the northern shrike, black in the loggerhead. Field marks such as these are well known today and it is no longer necessary to shoot a bird to ascertain its identity.

Lanius ludovicianus

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Laniidae

(Song; Call)

Shrikes are songbirds with hooked beaks and some of the attributes of birds of prey. Not confining their hunting to insects, they also kill mice and small birds. They have the habit of impaling their prey on thorns and the barbs of wire fences, presumably for later use; but they may, one suspects, sometimes forget where they put things. Of the two species of North American shrikes, the loggerhead is the more widespread.

Audubon portrays a pair of shrikes contending over a mouse and he makes the observation that these birds exhibited, even when mated, few of those marks of tender affection which other birds usually show. He said that although both sexes are quite alike, “I have thought it necessary to figure both, in order to shew the quarrelsome disposition of these birds even when united by the hymeneal band.”

Although Audubon regarded this species as basically southern, it was eventually found to be distributed over most of the United States as well as the southern tier of Canadian provinces. However, during the last twenty or thirty years it has declined drastically in the North, practically disappearing from New England and the Maritime Provinces. It is also showing a serious decline in the inland parts of its range. There is no clear explanation for the decline. In the south and parts of the West shrikes are still seen commonly on telegraph wires and fencelines.