GLEANERS OF FOREST AND MEADOW

Kingfishers, Woodpeckers, Tyrant Flycatchers, Larks, Swallows, Jays, Magpies, Crows, Titmice, and Nuthatches

Ceryle alcyon [Alcedo Alcyon]

Order: Coraciiformes

Family: Alcedinidae

Although there are eighty-seven kinds of kingfishers in the world, many of them adorned with tropical colors, only one is to be found in most of North America (although two others occur in Texas just north of the border). Audubon wrote, “Were I infected with the desire of giving new names to well-known objects, you may be assured that, notwithstanding the partly appropriate name given to this bird, I should call it . . . the United States Kingfisher. My reason for this will, I hope, become apparent to you when I say it is the only bird of its genus found upon the inland streams of the union.”

The belted kingfisher, relieved of competition with other members of its tribe, has a vast breeding range, extending from Labrador, James Bay, and Alaska south to the Gulf states and California. In winter some may travel as far as Panama, but a few remain as far north as the Great Lakes and New England, restricted only by the absence of open water.

Audubon noted that “mill ponds are favorite resorts of the Kingfisher, the usual calmness of the water in such places permitting it to discover its prey with ease. . . . The holes dug in the earth or sand by the species, in which it deposits its eggs, are generally found in places not far from a mill or by water.” He reports on the kingfisher’s edibility: “The flesh is extremely fishy, oily, and disagreeable to the taste. On the contrary, the eggs are fine eating.”

254. Northern Flicker [Golden-winged Woodpecker] i

Colaptes auratus [Picus Auratus]

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

(Kik-kik call; Peah call; Drum)

Lyrically Audubon wrote: “No sooner has spring called them to the pleasant duty of making love than their voice is heard from the tops of high decayed trees proclaiming with delight the opening of the welcome season. Their note is merryment itself as it imitates a prolonged and jovial laugh.” He adds that even in confinement, “the Golden-winged Woodpecker never suffers its naturally lively spirit to droop. By way of amusement, it will continue to destroy as much furniture in a day as can well be handled by a different kind of workman in two.”

Audubon spoke of the multiplicity of names that the flicker went by: ”High-holder, Yucker, and Flicker . . . seldom or never graced with the epithet Golden-winged, employed by naturalists.” As a matter of record, more than seventy local names were used at one time or another, but general usage finally decreed the name “flicker.”

For many years the flicker of the East was called the “yellow-shafted flicker,” while the one in the West was the “red-shafted flicker,” because the yellow areas were replaced by red. They were regarded as two distinct species until a recent decision of the American Ornithologists’ Union declared them conspecific, intergrading on the western edge of the Great Plains.

Audubon’s original composition showed only the three upper birds. Later he added the two lower males. He or his engraver may have copied the right-hand bird from plate 3 in Wilson’s American Ornithology.

Dryocopus pileatus [Picus Pileatus]

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

(Wuk call; Fast wuk series; Drum)

Second in size only to the mysterious and perhaps extinct ivory-billed woodpecker, the pileated woodpecker is still common in many parts of the United States. In some areas, such as New Jersey, where it apparently disappeared some years ago, it has made a strong comeback.

This handsome woodpecker must have been one of Audubon’s favorites, and, if we are to judge from the imagination and effort that went into this spirited composition, one of his finest. Using a combination of pencil, ink, watercolor, and egg white, he probably painted it in 1829 in Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania. He was of the opinion that the pileated was even more shy than the ivory-bill and that it seemed to know the distance that a gunshot would carry. This may partly explain why the pileated woodpecker survived and the ivory-bill did not, but a more likely reason lies in the food habits of the two species. The ivory-bill was a highly specialized feeder, the pileated less so, although it prefers carpenter ants. According to Dr. James Tanner, who did most of the basic research on the ivory-bill for the National Audubon Society, it takes about six square miles of virgin timber to support a single pair of ivory-bills, whereas the same area will support about thirty-six pairs of pileateds.

Even when they keep out of sight pileateds betray their presence by their diggings, large oval or oblong holes, and also by their loud, irregular, flickerlike calls.

Melanerpes erythrocephalus [Picus Erythrocephalus]

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

(Tchur call; Tchur call, chatter and drum; Alarm call; Drum)

This dashing woodpecker, so boldly patterned in red, black, and white, was undoubtedly much more numerous in Audubon’s day. He wrote: “It is impossible to form any estimate of the number of these birds seen in the United States during the summer months; this much I may safely assert, that a hundred have been shot upon a single cherry tree in one day.” Whereas this woodpecker once was widespread in the Northeast, its range has contracted considerably. Audubon mentioned that it was not uncommon in Nova Scotia, but it would certainly be a rare straggler there today.

This decline has been due, in part, to the advent of the starling, which takes over the nesting holes so laboriously hewn by the woodpecker. Another factor is its habit of sitting on fenceposts and flying low across the road when a car approaches, just in time to be dashed against the hood or windshield. Of all the roadside birds, this is the one that suffered most from the proliferation of motor vehicles. Today red-heads are still common enough in certain parts of the Midwest and South, but in nowhere near their former numbers. They prefer open woodlands or isolated park-like groves rather than solid forests. Most woodpeckers have a patch of red on the head and so are sometimes erroneously called red-headed woodpeckers. This is the only eastern woodpecker possessing a completely red head.

257. Yellow-bellied Sapsucker [Yellow-bellied Woodpecker] i

Sphyrapicus varius [Picus Varius]

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

(Call; Drum)

Bird artists of today, inhibited by their ornithological critics, seldom show the originality or spirited animation so characteristic of Audubon’s work. A woodpecker is usually shown clinging to a tree, with its tail braced in traditional woodpecker fashion; it would be considered daring to draw one dangling from a berry-laden branch as Audubon has pictured these sapsuckers. Yet Audubon must have witnessed such a scene.

The yellow-bellied sapsucker is the only eastern woodpecker in which the male has a red throat patch. But an easier way to identify it is the longish white patch that extends diagonally down the wing, as shown in the upper bird. Typical of the Canadian woodlands and the mountain country, the sapsucker is the most migratory of all the woodpeckers, sometimes traveling to the West Indies and Central America. It seems to have suffered a decline in recent years, virtually disappearing from the southern part of its breeding range in the Appalachians.

In a family of highly valuable birds that save millions of dollars of timber annually, this is the only one regarded as harmful. It has the habit of drilling rows of evenly spaced holes, and from these pits it gathers the tree’s oozing life blood, sopping it up with its brush-like tongue. Downy woodpeckers, squirrels, hummingbirds, and butterflies patronize the sapsucker’s wildwood bar, and sip the stolen brew when the bartender is away.

Clockwise from top center:

258. Hairy Woodpecker [Maria’s, Phillips’s, Canadian, Harris’s and Audubon’s Woodpeckers] i

Picoides villosus [Picus Martini, P. Phillipsi, P. Canadensis, P. Harrisi, P. Auduboni]

(“Pic” w/tapping; “Rattle”; “Wicka”; Drumming)

(Pic call; Rattle call; Drum)

Three-toed Woodpecker [Banded Three-toed Woodpecker] i

Picoides tridactylus [Picus Hirsutus]

(Pwik call; Rattle; Drum)

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

Audubon went wild in describing variants of the widespread hairy woodpecker as new species. A well-marked pair “procured in the neighborhood of Toronto in upper Canada, by a gentleman” were given the name “Maria’s Woodpecker, Picus Martini” in honor of Maria Martin, who painted many of Audubon’s backgrounds. Another bird collected in Massachusetts by Nuttall was named “Phillips’s Woodpecker” in honor of another friend, Benjamin Phillips. A larger, more northern form was named the “Canadian Woodpecker.” “Harris’s Woodpecker,” described from specimens taken on the Columbia River by Dr. Townsend, was named by Audubon in honor of another friend, Edward Harris. Finally, courtesy of Mr. Trudeau in Louisiana, Audubon gave his own name (“Audubon’s Woodpecker”) to a specimen taken in Louisiana.

Aberrant hairy woodpeckers, probably juveniles, can have yellowish caps, and therefore can be confused with male three-toed woodpeckers. However, the two birds with barred backs at the upper right were identified correctly as three-toed woodpeckers, a Canadian species that is quite distinct from the black-backed woodpeckers shown in plate 261. Both species share the same conifer forests in much of wooded Canada.

Picoides pubescens [Picus Pubescens]

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

(Pic call, Whinny call; Drum)

This, the most familiar woodpecker, probably enjoys the same range as it did in Audubon’s day. It undoubtedly declined prior to the turn of this century when deforestation was still in full stride, but is probably more numerous today for two reasons—first, because of the regrowth of the trees, but most especially, because of the handout of suet at backyard feeders across the land.

Audubon instructed Havell, the engraver, to put in more trumpet vine flower to fill out the space on this plate. His birds seem to represent the southern race of the downy which tends to have a smoky brown tinge on the underparts. He believed this was due to the burning of grass in the pine forest, which coats the tree trunks with carbonaceous material.

Defending the industry of the downy woodpecker or “sapsucker,” he wrote: “It perforates the bark of trees with uncommon regularity and care; and, in my opinion, greatly assists their growth and health and renders them more productive.” He added that there were not too many farmers who agreed with him.

The downy woodpecker is a sedentary species with a broad range from tree limit in Canada and Alaska to the Gulf states and California. Several subspecies have been described; these differ in measurements, the amount of white spotting, and other minor details.

260. Red-cockaded Woodpecker i

Picoides borealis [Picus Querulus]

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

(Call, drum; Call)

This white-cheeked woodpecker of the open pine forests of the South was obviously much more numerous in Audubon’s day. He wrote that it “is found abundantly from Texas to New Jersey, and inland as far as Tennessee.” Today, it still is found very locally in much of that area except the northeastern part. With the exception of an outpost colony in Maryland it is no longer found north of southeastern Virginia. But it has grown so sparse and local that it is now regarded as a critical species; not exactly on the endangered list, but one that bears close watching. Lumbering practices in many places have eliminated the trees with diseased hearts where this highly specialized woodpecker likes to dig its nesting holes.

In this plate, the bird in the center apparently was drawn from life. On July 29, 1821, Audubon captured a male that he painted at Oakley Plantation: “I put it into a cage, every part of which it examined, until finding a spot by which it thought it might escape, it began to work there, and soon made the chips fly off. In a few minutes, it made its way out, and leaped to the floor . . . hopped to the wall, and ascended as if it had been on the bark of one of its favorite trees. . . . I kept this bird two days, but when I found that the poor thing could procure no food, I gave it its liberty.”

261. Black-backed Woodpecker [Three-toed Woodpecker] i i

Picoides arcticus [Picus Tridactylus]

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

(Kyik call; Rattle-snarl; Drum)

(Pwik call; Rattle; Drum)

In the cold boreal forests that stretch across Canada and the northern fringe of the United States, this distinctive woodpecker can be found scaling the bark off spruce trees and other evergreens. It can be separated from its very similar relative by its solid black back. The other species has a barred back. Only the males have yellow caps. The barred flanks are distinctive in both species. Normally, this woodpecker is sedentary, but occasionally in winter it moves southward in small numbers to southern New England and the Great Lakes states.

Audubon called this species the “Arctic Three-toed Woodpecker,” a name applied to it until recently. He wrote, “This curious species of Woodpecker is found in the northern parts of the State of Massachusetts, and in all portions of Maine that are covered by forests of tall trees, in which it constantly resides. I saw a few in the great pine forests of Pennsylvania and my friend, the Reverend John Bachman, observed four near the falls of Niagara about twelve years ago, and is of the opinion that some may breed in the upper part of the State of New York. . . .”

Audubon is believed to have observed and painted this trio of woodpeckers in the “Great Pine Forest of Pennsylvania” in August, 1829, a date that would imply summer residence, and possible breeding. Today this species nests no farther south than the Adirondacks.

262. Ivory-billed Woodpecker i

Campephilus principalis [Picus Principalis]

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

(Kent calls and social chatter)

This, our most spectacular woodpecker, may now be extinct. Recent sightings remain unconfirmed, yet in Audubon’s day it was widespread and not uncommon throughout the swamp timber of the southeastern states. He reported that the crested head and white bill “forms an ornament for the war-dress of most of our Indians, or for the shot-pouch of our squatters and hunters. . . . On a steamboat’s reaching what we call a wooding place, the strangers were very apt to pay a quarter of a dollar for two or three heads of this woodpecker.” He adds: “I have seen entire belts of Indian chiefs closely ornamented with the tufts and bills of this species.”

This relentless persecution took its toll, but environmental changes were the principal factor in the bird’s disappearance. The ivory-bill needed large tracts of virgin forest where it could work mostly on trees that had been dead two or three years. It took about that long for decay to set in and the first insects to attack the wood—the fat whitish grubs of borers that tunnelled just beneath the tight bark. These grubs were the staple food of the ivory-bill. A year or so later, the subsurface borers disappeared. Decay ate deeper into the heartwood, and the ivory-bill would be forced to look elsewhere for its special food, which was getting increasingly hard to find.

Clockwise from top left:

Picoides villosus [Picus Villosus]

(“Pic” w/tapping; “Rattle”; “Wicka”; Drumming)

(Pic call; Rattle call; Drum)

Red-bellied Woodpecker i

Melanerpes carolinus [Picus Carolinus]

(Kwirr calls)

Northern Flicker [Red-shafted Woodpecker] i

Sphyrapicus ruber [Picus Mexicanus]

(Kik-kik call; Peah call; Drum)

Yellow-bellied Sapsucker [Red-breasted Woodpecker] i

Sphyrapicus varius [Picus Ruber]

(Call; Drum)

Lewis’s Woodpecker i

Melanerpes lewis [Picus Torquatus]

(Calls)

Order: Piciformes

Family: Picidae

This catch-all plate shows five species of woodpeckers, only two of which were well known to Audubon—the two hairy woodpeckers shown at the top left, and the two red-bellied woodpeckers at the upper right. Because of the variation in spotting he regarded the hairy woodpecker of eastern Canada and those of the far West as being several distinct species portrayed on plate 258.

The red-bellied woodpecker was one of the most abundant of the family in the South. Audubon wrote that in the pine barrens of Florida “on any day it would have been easy to procure half a hundred. . . . The officers and men of the United States Schooner Spark, as well as my assistants, always spoke of it by the name of ‘Chaw-chaw.’ Perhaps it partially obtained this name from the numbers of it cooked by the crew.”

The two central figures (quarreling) are the red-shafted western race of the northern flicker, the next two are Lewis’s woodpeckers, another western species, and the two birds at the bottom are the red-headed western relative of the yellow-bellied sapsucker. Audubon had never seen the latter three kinds in life.

264. Eastern Kingbird [Tyrant Flycatcher] i

Tyrannus tyrannus [Muscicapa Tyrannus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Call)

The white band crossing the tip of its tail is the “field mark” of the spirited kingbird. Its rapid sputter of bickering notes is a familiar sound along the rural roadside as it sallies forth to harass passing crows or even hawks.

Audubon, who used the names “Kingbird” and “Tyrant Flycatcher” interchangeably, defended this bird against its detractors by emphasizing its good qualities. “Man,” he wrote, “persecutes the Kingbird without mercy. . . . This mortal hatred is occasioned by a propensity which the Tyrant Flycatcher now and then shews to eat a honeybee, which the farmer looks upon as exclusively his own property. . . . Few hawks will venture to approach the farmyard while the Kingbird is near. . . . The many eggs of the poultry which he saves from the plundering crow, the many chickens that are reared under his protection, safe from the clutches of the prowling hawks, the vast number of insects which he devours, and which would otherwise torment the cattle and horses, are benefits conferred by him . . . and calculated to ensure for him the favor and protection of man.”

In spite of these good qualities the kingbird found its way to the pot. Audubon wrote, “The flesh of this bird is delicate and savory. Many are shot along the Mississippi, not because these birds eat bees, but because the French of Louisiana are fond of bee-eaters.”

265. Gray Kingbird [Gray Tyrant]

Tyrannus dominicensis [Tyrannus Griseus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Song; Calls)

The best place to see the “gray tyrant,” or “pipiry flycatcher,” as Audubon called it, is in the Florida Keys. There during the summer months it is abundant, sitting on the wires that follow the Overseas Highway. In April, it makes its oceanic flight from its winter resort in the West Indies.

Although in Florida the Keys suit them best because they are like the islands in the Caribbean where the species is most at home among the mangroves, gray kingbirds can be seen along both coasts of the peninsula—a few even in the northern parts of the state and beyond. They look much like ordinary kingbirds, but have a big-billed, bull-headed look and are of a pale washed-out gray color, without the band of white across the tip of the tail that marks the eastern kingbird. The tail is notched distinctly, and there is a dark ear patch. They are just as hot-tempered as their slaty-backed northern brethren, sallying forth to meet wandering crows or hawks, strafing, dive-bombing, and swearing at them in kingbird fashion. Their cry, less strident than the eastern kingbird, has given them the nickname “pipiry flycatcher.” All kingbirds belong to the flycatcher family, and sit on exposed perches as flycatchers do, waiting until insects fly by.

Tyrannus savana [Muscivora Savana]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song and calls [mixed])

Although this streamlined bird lives nowhere near our borders, it has been recorded at least a score of times north of Mexico, in a dozen states and provinces. Songbirds that live in the West Indies or in northern Mexico might be expected to cross the line once in a while—birds do not recognize political boundaries—but this is the only bird that lives deep in the tropics that has paid us so many visits. Most of these strays have appeared along the coast or not far from it, suggesting that tropical storms might have carried them northward. Audubon, who was incredibly lucky in the number of rarities he discovered during his lifetime, secured the bird figured here near Camden, New Jersey.

The normal range of the fork-tailed flycatcher is from southern Mexico to Patagonia, and travelers in the tropics find it a common bird, filling the niche of our kingbird along the roadsides. It has the kingbird’s temper, fearlessly chasing every hawk that soars by. Its kingbird-like bickering has the sound of castanets, appropriate in Latin America. The nearest thing to this species in the United States is the scissor-tailed flycatcher of Texas and Oklahoma, a bird equally streamlined, but pale gray with a touch of pink on its sides.

267. Great Crested Flycatcher i

Myiarchus crinitus [Muscicapa Crinita]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Call)

“The squeak or sharp note of the Great Crested Flycatcher is easily distinguished from that of any of the genus, as it transcends all others in shrillness, and is heard mostly in those dark woods where, recluse-like, it seems to delight,” Audubon wrote. He continued, “During the love-season it is heard for hours, both at early dawn and sometimes after sunset.”

The size and shape of a kingbird and just as belligerent, this flycatcher with the strident voice can be identified readily by its rusty tail and yellowish belly. Instead of building an open nest of sticks in some tree or shrub, it uses a natural cavity or an old woodpecker hole. The bulky mass of twigs and other materials almost always includes the shed skin of a snake or a substitute, such as a snake-like shred of cellophane. The snakeskin sometimes protrudes from the entrance hole like a latchstring; it might be assumed that this is deliberate so as to repel any mammalian intruder, but who knows?

The crested flycatcher has a broad breeding range east of the Rockies from the southern tier of the Canadian provinces to the Gulf of Mexico. In winter it retreats to the tropics, but a few linger in the southern tip of Florida and in southernmost Texas. There are similar species in the arid Southwest and in the American tropics, challenging the birder to identify them.

268. Eastern Phoebe [Pewit Flycatcher] i

Sayornis phoebe [Muscicapa Fusca]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Chip call and flight song)

The plain little phoebe is one of the better known birds because it enunciates its name distinctly. Sitting in an erect position on an exposed perch, from which it sallies forth for flying insects, it can easily be distinguished from the other smallish gray flycatchers by its habit of wagging or twitching its tail. Ever since the colonists first settled the land it has benefited by the human presence, building its well-padded nest in a shed, on a back porch, on barn rafters, or under a bridge.

Audubon, who called it the Pewit or Pewee Flycatcher, was fascinated by a family of these birds that lived in a cave on Perkiomen Creek near his home at Mill Grove in Pennsylvania, and it was there that he performed the first birdbanding experiment in America. He wrote, “I now took upon me to handle the young frequently. . . . I attached light threads to their legs; these were invariably removed, either with their bills or with the assistance of their parents. . . . At last when they were about to leave the nest, I fixed a light silver thread to the leg of each, loosely enough not to hurt the part, but so fastened that no exertion of theirs could remove it.” Next season after the phoebes’ return he found several nests along the creek and had the pleasure of finding two birds that still had the little ring of silver on the leg.

269. Acadian Flycatcher [Small Green-crested Flycatcher] i

Empidonax virescens [Muscicapa Acadica]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Call)

The Empidonax flycatchers are the despair of the birder. Unless they are singing it is often difficult to identify the five eastern species by appearance alone. Audubon, whose ear was not the best, recognized only two, the acadian and willow flycatchers, until late in his career when he became aware of two more, the least and yellow-bellied flycatchers.

These little flycatchers, smaller than a phoebe or a pewee, share a characteristic combination of whitish wing-bars and eye-rings. Their songs, habitats, nests, and to a certain extent their ranges distinguish them during the nesting season, but in migration it takes a real expert to sort them out.

The acadian flycatcher, the only one Audubon knew well, is the most southerly of the group, nesting in broad-leaf forests and swampy woodlands from the southern Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico and westward to the edge of the plains. Its “song” is an emphatic pit-see! with a sharp upward inflection.

Audubon obviously confused the yellow-bellied flycatcher with this somewhat similar species when he wrote that it is found “to the eastern extremities of Nova Scotia, proceeding perhaps still further north.” The acadian flycatcher has never been found nesting farther north than southern New England, where it has not appeared for fifty or sixty years, perhaps because of the chestnut blight. It now seems to be extending its range back into New England again.

270. Willow Flycatcher [Traill’s Flycatcher] i

Empidonax traillii [Muscicapa Trailli]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Creet call, song)

(Creet, song; Song; Whit call)

The Empidonax flycatchers, little mouse-colored birds with white eye-rings and light wing-bars, are the despair of the birder. The various species are so similar that they cannot be separated with certainty except when they sing, which they seldom do except on their breeding grounds.

Another clue to their identity is the environment or habitat that they choose. Audubon collected this obscure little bird at Fort Arkansas, a settlement on the Arkansas River about thirty miles from the Mississippi. It was new to him. He named the bird after Dr. Thomas Traill, an English friend who helped him while he was bringing his great work to publication.

“Traill’s flycatcher” was soon found to be quite widespread in the western, central, and northern parts of the United States; but it has been only in recent years that ornithologists have become aware that two very similar species were involved. Taxonomists renamed “Traill’s flycatcher” the willow flycatcher and its more northern and eastern counterpart was called the alder flycatcher. Although very similar in appearance, they can be distinguished readily by their songs—the alder flycatcher sings a well-accented fee-bee-o, while the willow flycatcher voices a sneezy fitz-bew.

The population of the willow flycatcher, the bird Audubon described, has been exploding in recent years, extending eastward and northward into the range of the alder flycatcher. Eventually, the alder flycatcher may lose out to competition from its close relative.

271. Eastern Wood-Pewee [Wood Pewee] i

Contopus virens [Muscicapa Virens]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Call; Call)

“It is in the darkest and most gloomy retreats of the forest that this Wood Pewee is generally to be found,” wrote Audubon. His name for the bird was in general use until very recently when birders decided to call it the eastern wood-pewee to differentiate it from the western wood-pewee, which has a nasal song and a darker breast.

Audubon thought the sweet, plaintive song of this bird—pe-wee, pettowee, pe-wee—to be “like the last sighs of a despondent lover, or rather like what you might imagine such sighs to be.” He noted that in the half light of dawn the pewee seemed to be “possessed of a peculiarity of vision, which enables it to see and pursue its prey with certainty, when it is so dark that you cannot perceive the bird, and are rendered aware of its occupation only by means of the clicking of its bill.”

This little grayish flycatcher can be separated from its cousin, the phoebe, by its whitish wing-bars. It does not bob its tail as a phoebe does. In summer its habitat is the leafy forest anywhere from southern Canada to the Gulf states and westward to the Great Plains. In winter pewees withdraw from the U.S. and populate the tropical forests from Costa Rica to Peru.

Contopus borealis [Muscicapa Inornata]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Call)

“It is difficult, for me,” Audubon wrote, “to understand how we should have in the United States so many birds which, not more than twenty years ago, were nowhere to be found in our country. Of these newcomers, the Olive-sided Flycatcher is one whose size and song render it very conspicuous among its kindred. That birds should thus suddenly make their appearance and at once diffuse themselves over almost the whole of the country is indeed a very curious fact. . . . The discovery of this species is due to my amiable and learned friend Nuttall.” Undoubtedly, this rather large flycatcher had been part of the American scene since time immemorial and Audubon was simply trying to rationalize his failure to find it earlier. It is a common bird during the summer in the forests of northern New England, across Canada to Alaska, and southward through the Rockies. Its song, uttered from a high perch at the tip of a spruce or fir, is a spirited whistle, “hip-three-cheers,” or “quick-three-beers.” It is understandable why Audubon missed it during his years in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Kentucky, and Louisiana, because one must be quite lucky to spot it during its migrations to and from the tropics.

After first seeing the bird near Boston with his friend Nuttall he found it elsewhere in Massachusetts, as well as in Maine and the Magdalen Islands on the coast of Labrador. He then wrote, “I have not yet been able to discover its line of migration or the time of its arrival in the southern states.”

Clockwise from top center:

273. Say’s Phoebe [Say’s Flycatcher] i

Sayornis saya [Muscicapa Saya]

(Song)

Western Kingbird [Arkansas Flycatcher] i

Tyrannus verticalis [Muscicapa Verticalis]

(Dawn song; Incipient locomotory hesitance and compound vocalizations; Compound and repeated vocalizations)

Scissor-tailed Flycatcher [Swallow-tailed Flycatcher] i

Tyrannus forficatus [Muscicapa Forficata]

(Song, calls)

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

This trio of western flycatchers was painted by Audubon in Charleston during the winter of 1836–37 from specimens sent to him by his friends Nuttall and Townsend, who collected them during their western travels. The two upper birds are Say’s phoebes. This rather large, gray-brown flycatcher of the West is a bit larger than the familiar eastern phoebe and may be known by the rusty belly, which suggests a small washed-out robin.

The bird at the lower left is a scissor-tailed flycatcher and, because of the relative shortness of the tail, seems to be an immature bird. Usually the outer tail feathers are much longer. It is a common bird in the southern Great Plains states but Aubudon never met it. Although it is the state bird of Oklahoma, it is known often as the “Texas bird of paradise.”

The bird in the center and the one at the lower right are western kingbirds which for many years were known to birders as “Arkansas kingbirds.” Although Audubon never saw one in life, he found a dead specimen “on the 10th of April, 1837, whilst on Cayo Island in the Gulf of Mexico.” His drawing, however, was made from skins furnished him by Dr. Townsend. The range of this attractive kingbird overlaps that of the eastern kingbird west of the Mississippi. It seems to be extending its range eastward and has bred occasionally in the vicinity of the Great Lakes. It is a sparse but regular migrant along the Atlantic coast in the fall.

Clockwise from top center:

274. Least Flycatcher [Little Tyrant Flycatcher] i

Empidonax minimus [Tyrannula Pusilla]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Song; “Whit” calls; “Twitter” or “weep-weep” calls; “Churr” call)

“Small-headed Warbler” [Small Headed Flycatcher]

“Wilsonia microcephala” [Muscicapa Minuta]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Parulidae

Alder Flycatcher [Short-legged Pewee] i

Empidonax alnorum [Muscicapa Phoebe]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Calls)

Black Phoebe [Rocky Mountain Flycatcher] i

Sayornis nigricans (Tyrannula Nigricans]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Tyrannidae

(Song; Call)

Yellow-green Vireo [Bartram’s Vireo]

Vireo flavoviridis [Vireo Bartrami]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Vireonidae

(Song)

“Blue Mountain Warbler”

“Dendroica montana” [Sylvia Montana]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Hirundinidae

Another catchall. The figure at the top seems to be the same bird that Audubon later figured (in reverse) as a least flycatcher, but here he followed Swainson’s nomenclature, supposing it to be different. The “Small-headed Flycatcher,” upper right, is an unknown. Audubon claimed that Wilson copied his drawing when he showed it to him in Louisville. No one has been able to figure out the identity of the bird. The “Blue Mountain Warbler,” upper left, is another unknown. It was drawn in London from a specimen from California.

The yellow-green vireo (left center) was procured in Mexico by William Swainson. Audubon stated that it “corresponds in every respect with those which I have myself procured in the states of New Jersey and Kentucky. I consider it a species generally overlooked in America . . . mistaken for the Red-eyed Vireo.” Actually, the yellow-green vireo does not occur north of the Rio Grande.

The rather indeterminate flycatcher at the lower right is almost certainly an alder flycatcher, if we can credit Audubon’s own account of its manner of nesting in Labrador. The black phoebe (bottom), a well-known western species, was drawn from a specimen procured by Nuttall in California.

275. Horned Lark [Shore Lark] i

Eremophila alpestris [Alauda Alpestris]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Alaudidae

(Song; Call)

Although there are seventy-five kinds of larks in the world, only one, the horned lark, is native to the Americas (the meadowlark is not a lark). A second species, the skylark of Europe, has been introduced on Vancouver Island. The horned lark is one of the most widely distributed songbirds in the Northern Hemisphere, breeding from the islands that rim the Atlantic Ocean south locally to northern South America and northern Africa. Audubon called it the “Shore Lark, “the name it has always been known by in England. It is an appropriate name, because the bird favors the beaches and the dunes. However, it will also resort to almost any open country—tundra, alpine meadows, plains, prairies, fields, etc.—where the grass is short.

It is quite obvious that Audubon knew the “shore lark” only as a winter visitor to the U.S. Since his time, it has extended its breeding range in the East considerably because of the replacement of forest by open fields and because of the creation of such “mini-prairies” as airports and golf courses. He wrote: ”The Shore Larks reach the United States at the approach of winter when the weather is severe in the north. . . . They become plump and fat and afford delicious food, for which reason our eastern markets are supplied with them.”

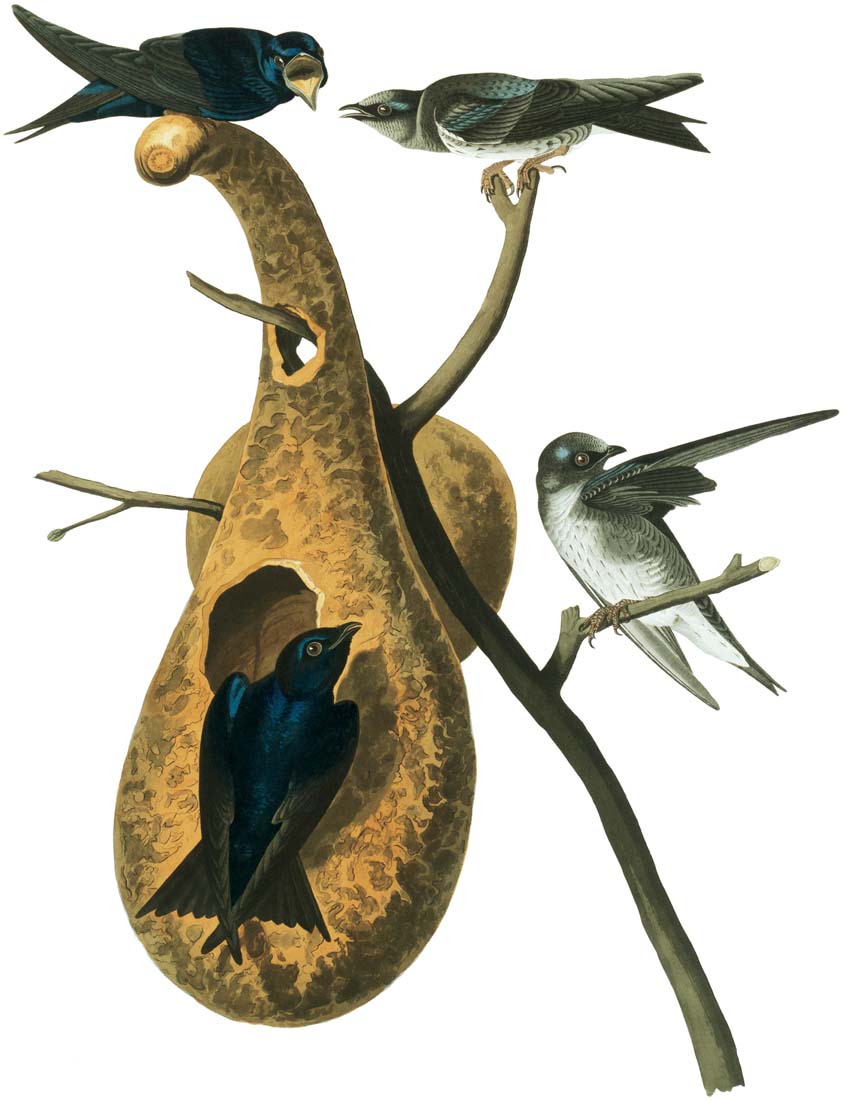

276. Tree Swallow [White-bellied Swallow or Green-blue Swallow] i

Tachycineta bicolor [Hirundo Bicolor]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Hirundinidae

(Song, calls)

The graceful little tree swallow is the hardiest of its tribe, summering as far north as Labrador and Hudson Bay. Its only limiting factor seems to be a hole in which to nest, and, when trees give way to open tundra, a bird box will entice it, even as far north as the Arctic Ocean in northwestern Canada.

Unlike most of the other swallows which leave our borders to spend the colder months in the tropics, the tree swallow remains along our southern coasts in winter. A few stragglers can be found at that season as far north as New Jersey and Long Island where, in the absence of insect fare, they subsist on bayberries. Like the martin, the tree swallow readily takes to bird boxes and it is just possible that this may have been a factor in the bluebird’s decline in the northern states. The gentle bluebirds are no match for the pugnacious tree swallows when it comes to a contest over a coveted box.

There probably has been no great change in the status of the tree swallow since Audubon’s day. It had already acquired by then the habit of nesting in boxes in lieu of woodpecker holes in some areas, notably in New England. At that time, however, tree swallows did not have the miles upon miles of telephone wires upon which to perch in cozy fashion as they do now during migration.

Hirundo rustica [Hirundo Americana]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Hirundinidae

(Song, calls)

“In spring,” Audubon wrote, “the Barn Swallow is welcomed by all, for she seldom appears before the final melting of the snows and the commencement of mild weather, and is looked upon as the harbinger of summer. As she never commits depredations on anything that men consider as their own, everybody loves her.”

This species and the bank swallow (plate 280) are the two most widely distributed swallows, ranging over both the New World and the Old. When Audubon drew his plate he applied the name Hirundo Americana, regarding our bird as distinct from the common swallow of Europe and Asia. Later, in his octavo edition, he lumped it, correctly, with the Old World form as Hirundo rustica. He wrote: “The song of our Barn Swallow resembles that of the Chimney [Barn] Swallow of England so much that I am unable to discern the small difference.”

The barn swallow is readily distinguished from other members of the family by its long outer tail feathers and the white spots that show when the tail is spread. Its rusty underparts are also distinctive. Although barn swallows nest widely in North America, wherever there are barns, it is only recently that they have been extending their range in the southeastern states, often nesting under road culverts and bridges. Except for a very few in the southern tip of Florida, all barn swallows leave the U.S. to winter in the tropics, where they can be found from Costa Rica to Argentina.

278. Cliff Swallow [Republican Cliff Swallow] i

Hirundo pyrrhonota [Hirundo Fulva]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Hirundinidae

(Song, calls)

The rusty or buffy rump is the badge of the cliff swallow, which in the days before barns must have depended on cliff sites for its colonies of juglike mud nests. When Audubon first saw this swallow in the spring of 1815, at Henderson, Kentucky, he named it “the Republican Swallow, in allusion to the mode in which the individuals belonging to it associate for the purpose of forming their nests and rearing their young.” Unfortunately, through the carelessness of his assistant, he wrote, “the specimens were lost, and I despaired for years of meeting with others,” but in 1819 Mr. Robert Best, curator of the Western Museum in Cincinnati, informed him “that a strange species of bird had made its appearance in the neighborhood, building nests in clusters affixed to the walls.” Audubon immediately crossed the Ohio to Newport in Kentucky: “No sooner were we landed than the chirruping of my long lost little strangers saluted my ears.”

Cliff swallows must have prospered and even extended their breeding range in the early years of the republic because of rural agriculture. In recent years many traditional colonies in the eastern part of the cliff swallow’s range have been abandoned, possibly due to a change in the construction of barns.

Audubon again documents edibility. He wrote of flocks of thousands one day late in November when “fourteen were killed at a single shot, all in perfect plumage and very fat. The markets were abundantly supplied with these tender, juicy and delicious birds.”

Progne subis [Hirundo Purpurea]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Hirundinidae

(Song, call)

There is a cult of the purple martin and as we drive through the towns and farms from southern Ontario to the Gulf states we see innumerable martin apartment houses erected on poles. Audubon noted that almost every country tavern had a martin box on the upper part of its signboard and he observed that the more handsome the box the better did the inn prove to be. But putting out houses to attract martins was traditional long before that. He mentions that the Indian “frequently hangs up a calabash on some twig near his camp and in this cradle the bird keeps watch and sallies forth to drive off the vulture that might otherwise commit depredations on the deerskins or pieces of venison exposed to the air to be dried. The slaves in the southern states take more pains to accommodate this favorite bird. The calabash is neatly scooped out and attached to the flexible top of a cane and placed close to their huts.” Audubon portrayed martins in such a gourd.

Originally, martins must have nested in the cavities of great trees, such as the ancient cypresses along the Mississippi, but today they nest almost exclusively in bird houses and about buildings. In the late summer, after the young are on the wing, they gather in large roosts and leave early for their tropical winter sojourn in Brazil, returning as soon as February to the Gulf states, where the advance guard is sometimes decimated by cold weather.

Clockwise from top center:

Tachycineta thalassina [Hirundo Mallissinus]

(Dawn song, calls)

Bank Swallow i

Riparia riparia [Hirundo Viparia]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Hirundinidae

When Aububon had this plate engraved he pasted together two separate drawings. The bank swallow at the bottom was drawn from birds he had collected in 1834 on the banks of the Schuylkill River near Philadelphia. Thirteen years later, in 1837, he painted the two violet-green swallows at the top from specimens sent to him from the Northwest by Nuttall and Townsend. Later, in his octavo edition, when the plates were miniaturized, he separated the two species and presented them again on individual plates.

The bank swallow is one of the two most widespread swallows in the world; the barn swallow (plate 277) is the other. Audubon was aware that the populations of these birds in the New World and the Old were conspecific, but when he produced his elephant folio and the Ornithological Biography he was of the belief that the brown-backed swallows he observed nesting in Louisiana were also bank swallows. It was not until he revised things in his octavo edition that he recognized the rough-winged swallow. He wrote, “No person seems to have been aware of the existence of two species of Bank Swallows in our Country, which however, I shall presently show to be the case.”

The main distinction from the rough-wing is that the bank swallow has a dark breastband and is a colonial nester. The violet-green swallow of the western mountains and valleys is rarely found east of the Rockies. Audubon never saw it.

Perisoreus canadensis [Corvus Canadensis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

The gray jay, which went by the name of Canada jay until recently, is a resident of the cool conifer forests that extend across Canada to Alaska and southward through the higher Rockies to Arizona and New Mexico. It is also known by such nicknames as “camp robber” and “whisky jack.”

Audubon, who knew the bird well in Maine, wrote that it also went by the name of “Carrion-Bird” and that it was often so bold as to enter the camps of the lumberers and rob them of the bait affixed to their traps. He reported that the men would amuse themselves during their eating hours with a game called “transporting the carrion-bird.” They would cut a pole eight or ten feet in length and balance it on the sill of the hut. This they would bait with a piece of flesh. When the jay alighted and was busy devouring the meat, the woodcutter within the hut would give a smart blow to the end of the pole, which drove the bird high in the air and not infrequently killed it.

Unlike the young of other jays, the dusky juvenile looks entirely unlike its parents. It is shown on plate 317. Audubon wrote: “I was induced to give the young of the Canada Jay simply because my friend, Mr. Swainson, formed of it a new species under the name of Garrulus Brachyrhynchus” (or “Short-billed Jay”).

Cyanocitta cristata [Corvus Cristatus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

The beautiful blue jay is a survivor, doing well these days, on our very doorstep. Many uncomplimentary things have been said about the jay. It has been called a “thief” because it pilfers acorns from the squirrel’s cache; a “tease” because it mobs the little blinking screech owl; and a “bully” because it chases other birds from the food shelf. It even has been labeled a “villain” for eating birds’ eggs, as the trio portrayed by Audubon are doing. But it is false to evaluate wild creatures according to human virtues and failings. For a blue jay to rob a nest is a natural act. Jays have helped themselves to eggs for centuries and still the small birds thrive; their reproduction rate is geared high enough to absorb such losses. If there were no natural checks, there would be so many warblers, vireos, and other small birds that their food supply of insects would give out and they would starve—or at least some of them would, until the balance was restored.

There is a “blue jay” of some kind in every state in the Union and in much of wooded Canada, but the three birds pictured here represent the real blue jay, a bird larger than a robin, with a blue back, a crest, and white spots in its wings and tail. It is definitely an “equal rights” bird. Males are identical to the females (not like the macho cardinal or tanager) and both birds share the nesting duties with equal devotion.

283. Scrub Jay [Florida Jay] i

Alphelocoma coerulescens [Garrulus Floridanus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

In Florida, look in the drab stretches of scrub oak for this handsome jay which Audubon has shown among the persimmons. Not so noisy as the blue jay, the scrub jay shows great curiosity when anyone invades the low scrub where it lives, and hopping to a bush top, sits with tail hanging down, watching and talking in low tones to the others of its flock. Alarmed, they all fly off, complaining in rasping accents.

Because of attrition of its environment—stretches of scrub oak which have been cleared for housing projects and other development—this attractive bird has been losing ground in Florida. It seems to be less adaptable than the blue jay, but much more confiding, often taking peanuts from the hand of a friend. Although local in Florida, and diminishing, other races or subspecies of the scrub jay are found widely in the western states and Mexico.

Judging by the fine execution of the persimmons, which seems to be the work of Joseph Mason, Audubon may have painted the jays in New Orleans, from a pair that were kept in a cage in that city (although they could not have originated in Louisiana). He wrote, “Their cage was usually opened after dinner, when both immediately flew upon the table, fed on the almonds that were given them and drank claret diluted with water.”

284. Magpie Jay [Columbian Jay]

Calocitta formosa [Garrulus Ultramarinus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

(Call; Song)

The spectacular magpie jay is one of several neotropical birds that Audubon attributed to North America on the basis of specimens that purportedly came from the Columbia River. Actually this bird must have come by ship from the west coast of Mexico. The only definite sighting of this species in the U.S. was of an individual that came daily to a feeding shelf in an Arizona border town. Although it could have strayed from its Mexican home, it was thought to be an escape from captivity.

Audubon wrote: “The specimen from which the drawings were taken was presented to me by a friend who had received it from the Columbia River.” He does not tell us specifically who that friend was, but it was probably Dr. Townsend. Confessing that he did not know the bird, he wrote: “Were I to relate to you, good reader, the various accounts which I have heard respecting this splendid bird, I should have enough to say; but as I have resolved to confine myself entirely to the results of my own observation, I must for the present remain silent on the subject.”

In view of the questionable validity of this species on the U.S. list, it was inappropriate for the postal service to have chosen to represent it on a U.S. stamp a few years ago in commemoration of John James Audubon.

285. Black-billed Magpie [American Magpie] i

Pica pica [Corvus Pica]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

The explorers Lewis and Clark, on their historical expedition, were the first to record the magpie in the United States. They saw their first ones near the great bend of the Missouri, and more as they proceeded westward. Although magpies are found over a large part of Europe and Asia, on our continent they are confined to the mountains and valleys of the West, particularly the arid sagebrush country. There, around the ranches, they are a striking sight as they fly with level flight across the field, white wing-patches flashing and long tails streaming out behind. From beak to tail they measure about twenty inches.

At this stage of Audubon’s work the West was still in the period of exploration. Many new birds were yet to be described, and because he could not set foot on all parts of the continent, he abandoned his earlier resolve to paint only from fresh specimens that he himself had taken. The black-billed magpie falls into this group. Some western birds were received from friends who were not always sure of their origin. Thus Collie’s magpie-jay, a magnificent long-tailed bird of southern Mexico, was recorded mistakenly by Audubon as coming from the Columbia River, and “Morton’s finch,” a Chilean bird, from California.

Modern ornithologists may criticize Audubon for these inaccuracies, but the fact remains that he was perhaps the greatest American ornithologist of his or any other period, a trailblazer at a time when our country was still a wilderness.

Corvus corax

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

This large relative of the familiar crow must have been at one time much more widespread in eastern North America if we are to judge from Audubon’s writings. But in his day wolves were also not uncommon in some districts. Like the wolf, the raven does not tolerate civilization, whereas their smaller relatives, the coyote and the crow, manage to coexist warily with man. Today, ravens are common enough in the West and in the wild lands of Canada, even as far north as the Arctic islands where they may be the only birds to be seen in the dead of winter. Within the confines of the eastern states they now extend southward only in the higher mountains, whereas Audubon found their nests in the rocky river gorges of Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York State. Recently, however, they seem to be increasing and extending their range in the Appalachians.

Audubon admitted, “I admire the Raven, because I see much in him calculated to excite our wonder. It is true he may sometimes hasten the death of a half-starved sheep or destroy a weakling lamb. . . . The more intelligent of our farmers are aware that the Raven destroys numberless insects, grubs and worms; he kills mice, moles and rats; he will seize the young weasel, the young opossum and the skunk; . . . our farmers are fully aware that he apprises them of the wolves prowling around the yard, and that he never intrudes on their cornfields except to benefit them.”

Corvus brachyrhynchos [Corvus Americanus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

It is quite likely that as the raven declined, the crow increased to fill the vacated niche. Or, to put it differently, it filled the newly-created niche—the farms and fields the raven found inhospitable. Like the raven, the crow found no respite at the hands of man and his firearms, but somehow the crow has managed to survive and even lives today in the parks of some of the large cities, having learned full well that it is quite safe there and that there is plenty of food to be found.

Audubon was indignant about the wanton killing of crows: “I tell you that in one single State, in the course of a season, 40,000 were shot. . . . The Crow devours myriads of grubs every day of the year that might lay waste to the farmer’s fields; it destroys quadrupeds innumerable, every one of which is an enemy to his poultry and his flocks.” He wrote that if it were not for the crow, “thousands of cornstalks would every year fall prostrate, in consequence of being cut over close to the ground by the destructive grubs we call ‘cut-worms.’” He wished that all Americans would be more “indulgent toward our poor, humble, harmless, and even serviceable bird, the Crow.”

After this little sermon, he wrote that “the young of our Crow, like that of the latter species [the raven], are tolerable food when taken a few days before the period of leaving the nest.”

Corvus ossifragus

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

A crow on the beach gives pause to the man with a glass. Is it an ordinary crow or is it a fish crow? True, there is a difference of three or four inches in their sizes, but one can’t be sure of size when the bird is standing alone, where there is nothing with which to compare it. But if the bird talks, it tells everyone within hearing what kind it is. If it caws an honest to goodness caw, then it is a common crow. If it says ca or cah in a nasal juvenile sort of way it is a fish crow—the small crow that lives along Atlantic tidewater from Long Island to the Gulf of Mexico and up the Mississippi River to Missouri. Audubon commented: “At times the sound of their voices seems as if in faint mimicry of that of the common crow, at others, one would suppose that they are troubled with a cough or cold.”

Fish crows can be found far up some of the large rivers that drain the Atlantic slope—the Hudson, Delaware, and Potomac, which are influenced by the tide. They are numerous around Washington, D.C., where they seem quite at home on the ledges of the Smithsonian, the National Museum, and the other government buildings that line Constitution Avenue. In Audubon’s day they fearlessly entered every coastal town, and they still do, but the much persecuted American crow is more wary.

Clockwise from top center:

289. Scrub Jay [Ultramarine Jay] i

Alphelocoma coerulescens [Corvus Ultramarinus]

(Shek-shek-shek call; Rattle and trill; Screech scolds)

Steller’s Jay i

Cyanocitta stelleri [Corvus Stellerii]

Clark’s Nutcracker [Clark’s Crow] i

Nucifraga columbiana [Corvus Columbianus]

Yellow-billed Magpie i

Pica nuttalli [Corvus Nutallii]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Corvidae

These four western members of the crow-jay family were drawn by Audubon from specimens sent to him by those western pioneers, Nuttall and Townsend. Although Audubon knew the scrub jay (top) in Florida, where there is a disjunct population, he shared the opinion of Bonaparte and others that the western birds were a separate species, differing only in minor details. His specimens apparently came from the Columbia River.

Steller’s jay, the dark bird at the upper right, is a denizen of the western fir and pine forests where it replaces the blue jay of eastern North America.

The large bird in the center is the yellow-billed magpie, which replaces the common black-billed magpie in the valleys of California. It is presumed to be a remnant population, descendants of an earlier invasion of magpies from the Old World, probably prior to the last glaciation. It has obviously been here long enough to develop specific differences. Audubon, naming it scientifically after his friend, Thomas Nuttall, wrote: “It is to him alone that we owe all that is known respecting the present species.”

The two birds at the bottom are Clark’s nutcrackers, or “Clark’s Crows” as Audubon called them. This species, a bird of the high Rockies, was named by Wilson in honor of William Clark, who with Meriwether Lewis commanded the historic overland expedition to the Pacific.

290. Carolina Chickadee [Black-capped Titmouse] i

Parus carolinensis [Parus Atricapillus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Paridae

(Song; Call)

Audubon, in this composition, was under the impression that he was painting the black-capped chickadee which he called the “black-capped titmouse,” a species that had already been well described by Wilson, Nuttall, and Swainson. It was not until he reached Eastport in the state of Maine, early in May of 1833, that he realized that there were two very similar chickadees and that the birds shown here, drawn near New Orleans, were an undescribed species. He recalled the morning in Maine when his friend, Lieutenant Green of the United States Army, entered his room and showed him a titmouse which he had just procured. “The large size of this bird, compared with those met with in the south, instantly struck me.” Later, after procuring specimens from South Carolina, Maryland, Massachusetts, and Maine, he and his friend, the Reverend John Bachman, examined and compared “many individuals of both species and satisfied ourselves that they were indeed specifically distinct.”

The breeding ranges of the Carolina chickadee of the South and the black-capped chickadee of the North overlap by a narrow margin in the states of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, and Kansas. The Carolina chickadee is sedentary, but during the winter there is some movement of black-caps, presumably first-year birds, into the realm of the Carolina chickadee. Aside from being as much as an inch smaller than the black-cap, the Carolina chickadee lacks the conspicuous white feather edgings in the wing.

291. Boreal Chickadee [Canadian Titmouse] i

Parus hudsonicus

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Paridae

This little brownish chickadee with the brown cap lives in the cold conifer forests that extend across Canada to Alaska. Although normally sedentary, a few may wander a short distance south of their home range during winters when black-capped chickadees are on the move. Occasional birds may even reach southern New England or the southern Great Lakes. The notes of this chickadee are slower, more drawling than the lively chick-a-dee-dee-dee of the black-cap.

There is an evolution in bird names. Audubon first called this little bird of the northwoods the Canada or Canadian titmouse; later in his octavo edition he changed it to “Hudson’s Bay Titmouse.” Succeeding ornithologists used the name “Hudsonian Chickadee,” and then changed it to “brown-capped chickadee.” Today the official name is boreal chickadee.

Audubon, reminiscing about his trip to the Maritime Provinces, wrote, “Nothing gave me more pleasure than the meeting with the bird long since discovered, at a time when I could fully study its habits. I had frequently searched for this interesting little titmouse in the State of Maine, where it breeds, but always without success, nor was it until I visited Labrador that I had an opportunity of seeing it.”

He painted the birds shown here in Labrador on July 20, 1833.

292. Tufted Titmouse [Crested Titmouse] i

Parus bicolor

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Paridae

(Song; Call)

Were it not for the tuft on its crown this little bird would be very plain indeed. Its ways are not unlike those of the more familiar chickadee to which it is closely related. Many of its notes are similar to those of the chickadee but more drawling and nasal. The song, however, is quite different—clear, whistled peter, peter, peter or here, here, here. Like its cousin the chickadee, it spends the night and lays its eggs in old woodpecker holes and tree cavities.

Audubon mentioned finding the “crested titmouse” as far north as Nova Scotia, but it is questionable that he really saw it there. During the early years of this century this rather sedentary bird was seldom found north of New Jersey. About the time the Hudson River bridges were built it breached that broad body of water and more recently it has spread explosively throughout much of New England, encouraged, unquestionably, by the largesse of suet and sunflower seeds. It has also crossed the Detroit River into southern Canada. It comes readily to take the sunflower seeds that are put out for it and, like the chickadee, grasps the seeds firmly in its claws or wedges them in crevices in the bark while hammering them open to extract the kernels. In its natural environment the titmouse depends on wild nuts such as beechnuts, hazelnuts, and acorns.

Clockwise from top center:

293. Bushtit [Chestnut-crowned Titmouse] i

Psaltriparus minimus [Parus Minimus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Aegithalidae

Black-capped Chickadee [Black-capt Titmouse] i

Parus atricapillus

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Paridae

(Song; Calls)

Chestnut-backed Chickadee [Chestnut-backed Titmouse] i

Parus rufescens

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Paridae

(Song; Calls)

This group of parids (the chickadee-titmouse family) shows three species. The two birds at the left are chestnut-backed chickadees, a western species that lives primarily in the humid forests along the Pacific slope from southern Alaska to central California, and locally inland to northern Idaho and northwestern Montana. It has the usual chickadee characteristic of black cap and black bib, but is distinguished from the others by the chestnut back. Its voice is hoarser than that of the black-capped chickadee with which it sometimes shares the woodlands. The specimens from which Audubon drew his figures were sent to him from the forests at the mouth of the Columbia by John Kirk Townsend.

The common bushtits at the upper right were also procured by Dr. Townsend, and their pendulous nest was furnished by his associate, Mr. Nuttall. It is a widespread species in the oak, pinon, and juniper forests of the United States.

The black-capped chickadee (lower two birds) was not familiar to Audubon prior to his trip to Maine, and, unknowingly, he had drawn his Carolina chickadee (on plate 290) in the belief that they were this species, which had already been well documented by Wilson. Later he acknowledged this error and described the Carolina chickadee as a new species.

294. White-breasted Nuthatch [White-breasted Black-capped Nuthatch] i

Sitta carolinensis

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Sittidae

(Song; Call)

(Song; Call; Call)

The nuthatches are the “upside-down birds,” for unlike the woodpeckers which always hitch their way upwards with the tail pressed against the trunk of the tree, nuthatches proceed head downward, thereby gaining a fresh perspective on any cracks or crevices.

The white-breasted nuthatch is the largest of our nuthatches and is identified readily by its black eye on a white face, free of the cap or an eye-line. Everyone in this enlightened day and age loves the nuthatch and puts out suet and sunflower seeds for its pleasure, but it was not always so. Audubon writes, “Now and then it has a quaint look, while watching the observer, clinging to the bark head downward, and perhaps only a few feet distant from him whom it well knows to be its enemy, or at least not its friend, for many farmers, not distinguishing between it and the Sap-sucker . . . shoot at it, as if assured that they are doing a commendable action.”

Audubon, assuming the role of the prophet in a new land, wrote, “Only four species of Nuthatch have as yet been observed within the limits of the United States. My opinion, however, is that at least two more will be discovered.” His prophecy was never fulfilled; there are but four, the white-breasted, red-breasted, brown-headed, and pygmy. The last two are so similar some systematists would lump them as conspecific.

Sitta canadensis

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Sittidae

(Song; Call)

This, the northernmost member of the nuthatch family, is a resident of the cold boreal forests stretching across Canada to southeastern Alaska, with outpost populations in the higher Appalachians to North Carolina, and in the high Rockies to Arizona.

Some winters, most of the birds are sedentary within this vast range; other years, there may be a mass withdrawal which may take some birds to the Gulf states and even occasionally to the border states of Mexico. Such mass movements may start as early as August, long before there is a hint of winter in the air. The presence of these little travelers is heralded by their nasal notes, higher than those of the white-breast, suggesting a baby nuthatch or a tiny tin horn. The clinching field mark of this rusty-breasted species is the broad black line through the eye.

Occasionally, these little nuthatches, taking off from the Maritimes on their southward travels, come aboard ships well out at sea. Audubon observed one of these waifs: “On one of my migrations from Europe to America, and at a distance of 300 miles from land, I saw one of these birds come on board one evening, during a severe gale.”

A peculiar habit of this little cavity-nesting bird is to line the entrance hole with pitch so as to discourage insects, mice, or other small birds from entering. On at least one known occasion, the nuthatch itself became stuck in the entrance hole and died.

Sitta pusilla

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Sittidae

This little nuthatch of the open pine forest ranges throughout the low country and the Piedmont of the southeastern states, from coastal Maryland to south-central Florida and westward through the Gulf states to east Texas. Unlike the other two eastern nuthatches, it travels amongst the trees in groups, keeping contact by means of piping unnuthatchlike notes—a rapid, squeaky kit-kit-kit or ki-dee-dee. Audubon wrote, “These birds pursue their avocations with so much cheerfulness that the woods echo to their notes. I have seen a congregation of these Nuthatches, amounting to fifty or more, thus perambulating the Floridas in the months of November and December.”

Aside from diminutive size, this species can be readily distinguished from its white-breasted and red-breasted relatives by its brown cap which extends down to eye level. A small whitish spot shows on its nape where the brown cap meets the gray back. The pygmy nuthatch of the western pine forests (next plate) is extremely similar in appearance and habits. Although this is a sedentary species which would not be expected to stray outside its normal range, there have been accidental records as far north as Iowa, Wisconsin, Illinois, and New York.

Clockwise from top center:

Certhia americana

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Certhiidae

(Song; Call)

(Song; Song, call [mixed])

Pygmy Nuthatch [Californian Nuthatch] i

Sitta pygmaea [Sitta Pygmea]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Sittidae

In this composition, Audubon pasted two brown creepers (the upper bird and the flying bird) onto his painting of two pygmy nuthatches. The brown creeper, in Audubon’s day, was also called the “Gleaner.” It is a slim, well-camouflaged brown bird that ascends each tree spirally, before flying down to the base of the next one. It digs no hole as a woodpecker does, but places its nest behind a loose strip of bark.

Audubon did not have much to say about the pygmy nuthatch (the two lower birds on the branch). He called it the “California Nuthatch,” and he wrote, “The figures of this species were drawn from a specimen kindly lent me by the council of the Zoological Society of London. It was procured by Captain Beechey in upper California, and is therefore entitled to a place in our fauna. Nothing is known of the habits of this bird, nor do I even know the sex of the individual figure.”

The pygmy nuthatch is very much like the brown-headed nuthatch of the southeastern states and is its ecological counterpart in the yellow pine forests of the West. Its range is much more extensive, stretching from southern British Columbia to central Mexico.