UPLAND GAMEBIRDS AND MARSH-DWELLERS

Grouse, Ptarmigan, Quails, Turkeys, Cranes, Limpkins, Rails, Gallinules, and Coots

118. Blue Grouse [Long-tailed or Dusky Grous] i

Dendragapus obscurus [Tetrao Obscurus]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Male song; Female calls)

Audubon, who called this bird the “dusky grous,” had never seen it in its native haunts, so he wrote, “I am obliged to have recourse to the observations of those who have had opportunities of studying its habits. The only accounts that can be depended upon are those of Dr. Richardson, Mr. Townsend and Mr. Nuttall.” At least one of the birds, the female at the right in this painting, was drawn from a specimen sent to him by Mr. Townsend.

This dusky gray or blackish grouse of the coniferous forests of the west ranges widely from southeastern Alaska and western Canada southward in the humid coastal belt to northern California, and in the higher mountains to southern California, Arizona, and New Mexico.

When courting, the male gives five to seven muffled hooting notes, so low in pitch that they escape the ears of some listeners. Audubon quoted Nuttall’s apt description: “The male at various times of the day makes a curious uncouth tooting, almost like the sound made by blowing into a bung-hole of a barrel, boo, wh’h, wh’h, wh’h, wh’h, the last note descending into kind of an echo. We frequently tried to steal on the performer, but without success, as, in fact, the sound is so strangely managed that you may imagine it to come from the left or right indifferently.” This ventriloquial effect has been commented on by many birders who have sought a glimpse of this elusive grouse.

119. Spruce Grouse [Spotted Grous] i

Dendragapus canadensis [Tetrao Canadensis]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Call; Display flight)

Audubon went to the state of Maine to observe the habits of this dark, secretive grouse and, although he succeeded, the task, he admitted, was perhaps as severe as any he ever undertook. “These breeding grounds,” he wrote, “I cannot better describe than by telling you that the larch forests, which are there called ‘Hackmetack Woods,’ are as difficult to traverse as the most tangled swamp of Labrador. . . . We sunk at every step or two up to the waist, our legs stuck in the mire and our bodies squeezed between the dead trunks and branches of the trees, the minute leaves of which insinuated themselves among my clothes, and nearly blinded me. We saved our guns from injury, however, and seeing some of the Spruce Partridge before they perceived us, we procured several specimens.”

There is some evidence that the spruce grouse may not be as abundant today as it was in earlier times. It is no longer easy to find, at least in the more southern parts of its range; possibly it is dropping out gradually because of the warming trend of the climatic cycle.

Audubon was confident that the bird that had been named Franklin’s grouse, and which for many years thereafter has been treated as a distinct species, was the same species as the spruce grouse. In this view Audubon has been vindicated. Recently the A.O.U. Checklist Committee has decreed that the two birds are conspecific, differing mainly in the spotting on the tail and tail coverts.

120. Ruffed Grouse [Ruffed Grous] i

Bonasa umbellus [Tetrao Umbellus]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Male drum; Female alarm and chick calls)

The ruffed grouse was obviously Audubon’s favorite game bird, as it is today for many sportsmen. During his era there were no game laws dictating the bag limit or the season when grouse could be taken. He himself shot them at all times of the year.

In former days the ruffed grouse was known as “pheasant” by country folk in the Appalachians and westward, while in New England it was called “partridge.” These names persist to this day among some sportsmen.

This large red-brown or gray-brown chickenlike bird of the brushy woodlands usually is not noticed until it explodes into the air with a startling whir. Two basic color types occur: reddish birds with rufous or reddish tails such as Audubon depicted, and gray or gray-brown birds with grayish tails. In the east, red birds are preponderant in the southern part of the bird’s range, which extends to the southern Appalachians, and gray birds predominate in the north. In the west, red birds are typical of the Pacific states, gray birds of the Rockies.

The “drumming” of the cock grouse is heard best in the early morning as it stands on a woodland log and beats its wings against its body. The muffled thumping starts slowly, accelerating into a whir: Bup . . bup . . bup . . bup . . bup . . bup . . bup . . uprrrr. Audubon admits that he often lured drumming males to his gun by beating on an inflated bladder.

121. Willow Ptarmigan [Willow Grous or Large Ptarmigan] i

Lagopus lagopus [Tetrao Saliceti]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Male calls; Male flight call)

Like the foxes and hares of the Arctic, this grouse of the frozen north changes its brown summer dress at the approach of winter, becoming an immaculate white except for its tail, beak, and eyes, which remain black. The willow ptarmigan, like the rock ptarmigan, is circumpolar, inhabiting the cold lands beyond tree limit from Newfoundland across the Hudson Bay area and northwestern Canada to Alaska and also the tundras of Siberia and northern Europe. In winter it seeks the sheltered valleys, where it ekes out a living in the willow scrub. Some willow grouse migrate southward beyond the breeding range at that season and occasionally or accidentally reach the northern extremities of New England and the Great Lakes states.

The red grouse of England is closely related, but remains rusty-red throughout the year, never developing a white winter plumage. Although it has been regarded as specifically distinct, it can be argued that the red grouse is merely a distinctive race or subspecies of the willow ptarmigan confined to the British Isles.

Audubon drew the pair represented in this plate with their young from specimens taken by George Shattuck of Boston, one of his Labrador party. The birds are in full summer dress.

122. Rock Ptarmigan [Rock Grous] i

Lagopus mutus [Tetrao Rupestris]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Male display; Flush call)

Although Audubon found the willow ptarmigan when he and his party explored the avifauna of Labrador, he did not encounter the rock ptarmigan, but he was aware of its existence. He wrote, “Whilst at Labrador, I was informed by Mr. Jones that a smaller species of Ptarmigan than that called the Willow Grouse, Lagopus Saliceti, was abundant on all the hills around Bras d’Or, during the winter, when he and his son usually killed a great number, which they salted and otherwise preserved; and that in the beginning of the summer they removed from the coast into the interior of the country, where they bred on open grounds. . . . They seldom appear at Bras d’Or until the last of the Wild Geese have passed over, or before the cold has become intense, and the plains deeply covered with snow. . . . They keep in great packs, and when disturbed are apt to fly to a considerable distance.”

Like the willow ptarmigan, the smaller rock ptarmigan is circumpolar, but tends to be more high arctic in distribution, often living above timberline in the mountains and descending to lower levels in winter. Some races of the rock ptarmigan are grayer than the birds shown here, and more finely barred. In white winter plumage the rock and the willow look very much alike, but the rock ptarmigan has a smaller bill, and males usually have a black spot before the eye. Audubon made his drawing from specimens presented to him by Captain James Ross of the Royal Navy.

From left to right:

123. Rock Ptarmigan [American Ptarmigan] i

Lagopus mutus [Tetrao Mutus]

(Male display; Flush call)

White-tailed Ptarmigan [White-tailed Grous] i

Lagopus leucurus [Tetrao Leucurus]

(Male flight scream and other calls; Male clucks)

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

Like the willow ptarmigan, the rock ptarmigan is circumpolar, but because of geographic variation it often has been a puzzle to systematic ornithologists. Audubon was no exception. Although he had drawn and described the rock ptarmigan earlier (see plate 122) he thought the bird shown here (left) was the same as the common ptarmigan of Britain. Later he changed his mind, and in his octavo Birds of America he described it as a new species, changing the scientific name from Tetrao Mutus to Tetrao Americanus. It seems to be a rock ptarmigan changing into winter plumage. It was drawn from a specimen loaned to him by Lord Stanley, the fourteenth Earl of Derby, and presumably came from the Canadian Arctic.

Never having seen the white-tailed ptarmigan alive, Audubon devoted scarcely more than a single paragraph to it: “This pretty little grouse,” he wrote, “is an inhabitant of the Rocky Mountains, where it was found by Mr. Douglas and afterwards by Mr. Drummond who sent several specimens to England. It is said to extend to as far as the Columbia River. All that is known of its habits is that they resemble those of the Ptarmigan. . . . My figure was drawn from the only specimen now in the museum of the Zoological Society of London.” The white-tailed ptarmigan, which lives on the alpine summits of western North America, is pure white in winter except for black eyes and a black bill. The other two ptarmigans have black tails at all seasons.

124. Greater Prairie Chicken [Pinnated Grous] i

Tympanuchus cupido [Tetrao Cupido]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Males displaying at lek)

When Audubon was a young man in Kentucky he found pinnated grouse (prairie chickens) “so abundant that they were held in no higher estimation as food than the most common flesh, and no hunter of Kentucky deigned to shoot them. They were looked upon with more abhorrence than the crows.” He reported that a friend who was fond of rifle-shooting “killed upwards of 40 in one morning, but picked none of them up, so satiated with grouse was he.”

He added: “Such an account may appear strange to you, reader; but what will you think when I tell you, that, in that same country, where twenty-five years ago they could not have been sold at more than one cent apiece, scarcely one is now to be found? The grouse have abandoned the state of Kentucky, and removed (like the Indians) every season further to the westward, to escape from the murderous white man.” He reported that the eastern race of the prairie chicken (the now extinct heath hen) had become “so rare that in the markets of Philadelphia, New York and Boston, they sell at from five to ten dollars the pair.” At that time they were still abundant on the midwestern prairies, but this too was to change, mainly because the bird could not adapt to modern agricultural practices. When the native prairie vegetation was eliminated they soon disappeared. Today the remaining populations, much restricted, are carefully managed. An organization in Wisconsin—The Tympanuchus cupido Society—is dedicated to purchasing, preserving, and managing remaining prairie chicken habitat.

125. Sharp-tailed Grouse [Sharp-tailed Grous] i

Tympanuchus phasianellus [Tetrao Phasianellus]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Males displaying at lek)

Superficially rather like a prairie chicken, this grouse of the brushy prairie, open thickets, and forest edges of the Northwest can readily be known by its short pointed tail that shows considerable white at the sides as the bird flies away. By contrast, its similar relative the prairie chicken has a rather short, rounded, black tail. Whereas the cock prairie chicken in display inflates orange neck sacs and erects hornlike neck feathers above its head, the sharp-tailed grouse bows low, lifts its tail high, and inflates purplish neck sacs. This is accompanied by quill rattling and rapid foot shuffling. The formalized mating dances of these grouse undoubtedly inspired some of the dances of the plains Indians.

Inexplicably, Audubon did not encounter this grouse on his upper Missouri journey. The specimens from which he drew his plate were undoubtedly furnished by Dr. Townsend. The sharp-tail has a wide range in western Canada and Alaska but has declined or disappeared in some of the prairie states. It once occurred south to Kansas, Iowa, and Illinois. The clearing of the brushy prairie for agriculture eliminated the habitat necessary for its survival.

126. Sage Grouse [Cock of the Plains] i

Centrocercus urophasianus [Tetrao Urophasianus]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Male popping display)

This, the largest grouse of North America, was called the “pheasant-tailed grouse” or “cock of the plains” by Audubon, who in his travels on the upper Missouri did not quite reach the western country where it is found. The sage grouse is noted for its extraordinary dance, which Audubon attempted to portray although he had not witnessed it. The dance in an arena amongst the open brush is a communal affair. A number of males, each one well-spaced, dance with their spiky tails spread and their yellow neck sacs inflated. A single dominant cock mates with a majority of the hens. He is surrounded by several sub-cocks or “guards” who keep off the lesser gentry and manage to do a minimal amount of mating. Most of the other males just dance.

Originally the sage grouse was found in fifteen of the western states, wherever sagebrush flourished. It was the principal upland game bird in nine of them. Overgrazing and drought during the 1930s nearly brought the sage grouse to the status of an endangered species; by the early 1930s it was hunted in only four states, and by 1937 only Montana had a regular open season. This was closed in 1943. The bird was gone from British Columbia, Nevada, Nebraska, and Oklahoma. The survivors started to recover by the 1950s, and today the sage grouse has an estimated total population of 1,500,000 birds of which 250,000, or one-sixth, are shot annually. However, if more millions of acres of sagebrush are removed, the species may take another nosedive.

Clockwise from top center:

127. Red-shouldered Hawk [Red-shouldered Buzzard] i

Buteo lineatus

Order: Falconiformes

Family: Accipitridae

See plate 96.

Northern Bobwhite [Virginian Partridge] i

Colinus virginianus [Perdix Virginiana]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

This, one of Audubon’s most involved and animated compositions, shows an immature red-shouldered hawk scattering a covey of bobwhite. Today’s wildlife management experts would be critical of Audubon for portraying them thus, because no covey of quail normally would expose themselves to predation in such open moorlike terrain. Audubon may be excused for taking artistic liberties because grass and brush, although ecologically correct, would have obscured the dramatic action.

The bobwhite, widespread in the eastern and central states, is undoubtedly the most popular American game bird. Other races or subspecies flourish in Cuba, Mexico, and Guatemala. All whistle the familiar bob-white! or poor, bob-white! In the northern states when these quail have become depleted by exceptionally cold winters, game departments have often reinforced their numbers with hatchery-raised stock.

Coveys of quail may wander in loose association throughout the day, but when evening approaches the “covey call” can be heard, a loud whistled ka-loi-kee! This is answered by whoil-kee! Once assembled they go to bed in a ring with tails together, their heads facing outward. If they are disturbed during the night they explode like a bomb, each bird going in a different direction without bodily interference, avoiding some of the chaos that Audubon suggests in this painting.

128. California Quail [Californian Partridge] i

Callipepla californicus [Perdix Californica]

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Advertisement call; Assembly call)

This attractive quail with the recurved topknot is the state bird of California. It was unknown in life to Audubon, who never visited the Pacific states, but was figured by him from specimens collected by Dr. Townsend near Santa Barbara in 1837. He wrote, “This beautiful species was discovered in the course of the voyage of La Perouse, and figured in the atlas accompanying the account of that unfortunate expedition, but without any other notice respecting its habits or distribution, than an intimation of its having been found abundant in the plains and thickets of California, where it formed large flocks.”

The range of the California quail now extends for more than two thousand miles from the southern tip of the Baja peninsula in Mexico northward through the Pacific states to southernmost Vancouver and the Okanagan Valley of British Columbia. Formerly it ranged north only to southern Oregon, but game commissions and sportsmen introduced it widely, extending its domain through much of Oregon and Washington to southern British Columbia, with outpost populations in Nevada, Idaho, Utah, Hawaii, and elsewhere. Its loud, three-syllabled call, qua-quer’go or where are you? is a familiar sound in coastal scrub and chaparral, along woodland edges, and in parks, country estates, and farms. In the desert regions of the southwest it is replaced by the similar Gambel’s quail, which was not differentiated in Audubon’s time.

From left to right:

129. Mountain Quail [Plumed Partridge] i

Oreortyx pictus [Perdix Plumifera]

(Song)

Crested Bobwhite [Thick-legged Partridge]

Colinus cristatus [Perdix Neoxenus]

(Song)

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

The mountain quail, which Audubon called the “Plumed Partridge,” ranges through the brushy mountain slopes of the Pacific states from the Canadian border to northern Baja California, with intrusions into western Idaho and Nevada. Its long attenuated head plumes and the broad white bars on the sides are shown well in the two birds on the left, which Audubon drew from specimens. He wrote, “Of this beautiful bird little, I believe, is known.” He then quoted Mr. Townsend who furnished the female specimen: “This bird inhabits the dense woods along the tributary streams of the Columbia River, and is said to extend south into California. . . . In all my rambles through the Oregon country I was never so fortunate as to meet with this pretty bird, the three specimens which I received have been procured by others.” The male bird was drawn from a specimen in the Museum of the Zoological Society of London.

As for the crested bobwhite (right) Audubon writes, “Nothing is known of this species further than that it was procured in the course of Captain Beechey’s voyage, on the northwest coast of America. My drawing was taken from a specimen kindly lent to me by the council of the Zoological Society of London.” Obviously this species, a sedentary Central American bird, has no place on the North American list.

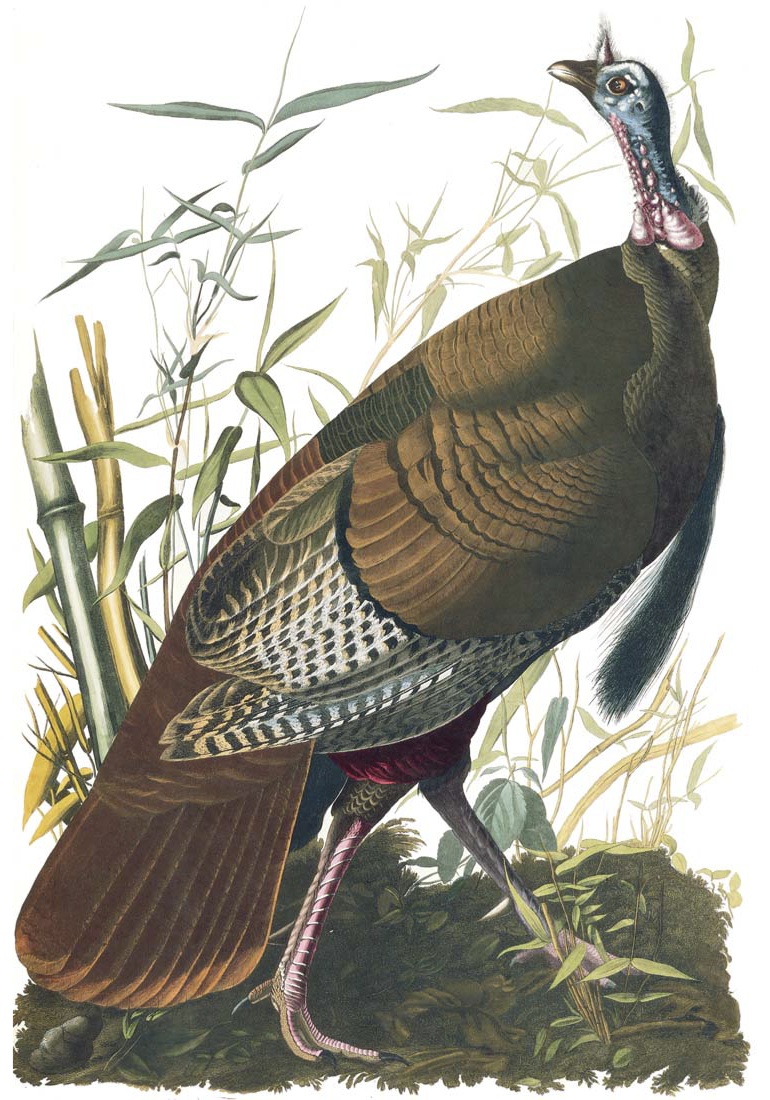

130. Wild Turkey [Great American Cock] i

Meleagris gallopavo

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Gobble; Calls)

Today a single print of Audubon’s wild turkey cock would bring at auction many times the original subscription price of the entire collection of 435 prints in the Elephant Folio.

In Audubon’s day the wild turkey was still widespread east of the Rockies but already diminished or absent in some of the more northerly parts of its range, which in colonial days extended to New England and southern Ontario. When he wrote the biography of this noble fowl Audubon noted that turkeys were becoming “less numerous in every portion of the United States, even in those parts where they were abundant thirty years ago.” He recalled that in earlier days in Kentucky he had seen birds of 10 to 12 pounds offered for three pence each, and “a first rate turkey weighing from 25 to 30 pounds avoirdupois was considered well sold when it brought a quarter of a dollar.” However, by 1836–37 they had risen in price to 75 cents in the markets of Washington. By this time domestic turkeys were beginning to fill the void.

After the wild stock had become much reduced in numbers, game management practices effected a comeback, and today at least 1,500,000 wild turkeys are to be found in 47 states, including many areas in the West beyond the ancestral range of the bird. The National Wild Turkey Federation, which is dedicated to a program of reintroduction and management, has a membership of more than 35,000.

131. Wild Turkey [Great American Hen] i

Meleagris gallopavo

Order: Galliformes

Family: Phasianidae

(Gobble; Calls)

The original painting of the “Great American Hen” and her chicks differs quite considerably from the print as it was engraved by Havell. It was executed in three mediums. The drawing of the hen was made in pastel to which watercolor was added when he introduced the chicks. Later a background was painted in with oil. In the print the rather muddy oil background was dropped out and the design gained a fresher look.

The wild turkey, a truly American bird, must have been a favorite of Audubon’s because he wrote a more lengthy account of it in his Ornithological Biography than he did of any other species. It has remained one of the most extensive accounts of this noble gamebird to be found in any book.

The name “turkey” seems illogical, as the original stock from which the domestic turkey has evolved came from Mexico and was transported to Europe by the Spanish conquistadors. Later it was brought back to the continent of its origin, where farm-bred birds sometimes hybridize with the wild ones. Audubon knew this. He wrote, “Wild Turkey cocks sometimes pay their addresses to the domestic females, and are generally received by them with great pleasure, as well as their owners, who are well aware of the advantages resulting from such intrusions, the half-breeds being much more hardy than the tame, and, consequently are easily reared.” Domestic turkeys have white tips to their tails; wild turkeys have bronzy tips.

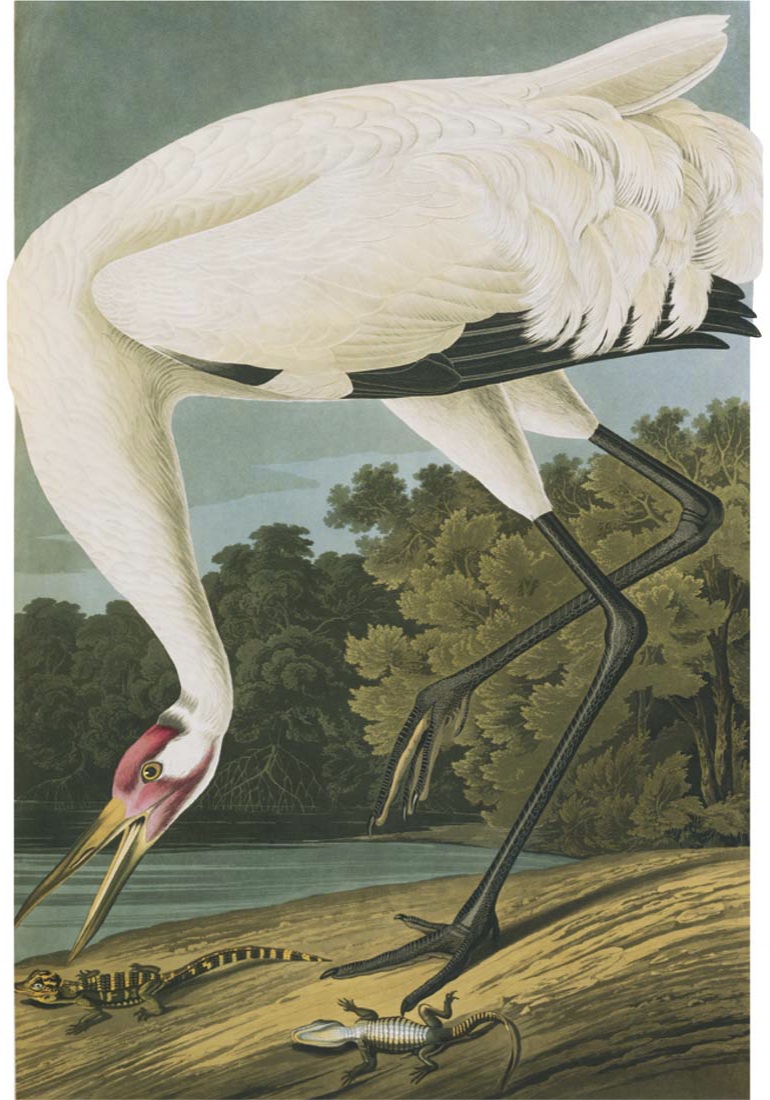

132. Whooping Crane [Hooping Crane] i

Grus americana

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Gruidae

(Calls from a pair)

To North Americans the whooping crane is the most publicized “endangered species.” It is with some shock that we learn that Audubon himself killed seven with two shots, a remarkable feat inasmuch as these wary birds are almost impossible to approach if a man is carrying a gun.

In his account of this species he states that during its winter sojourn in the south it was “abundant in Georgia and Florida, and from thence to Texas.” But, inasmuch as he believed the sandhill crane to be the young of the whooping crane, such statements are suspect. There may never have been as many whooping cranes in the early days as we have been led to believe. However, there is no question that they were much reduced until by 1948 there were less than three dozen whoopers in the world. By 1953 the number had dropped to about 23. Since then, due to the cooperative efforts of the National Audubon Society, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the Canadian government, the whooping crane population has climbed slowly but steadily to well over 200, including some in captive rearing programs. Single eggs taken from wild birds are put in the nests of sandhill cranes that act as foster parents. The main flock makes an annual journey from Wood Buffalo Park in northwestern Canada to the Aransas Wildlife Refuge on the central coast of Texas.

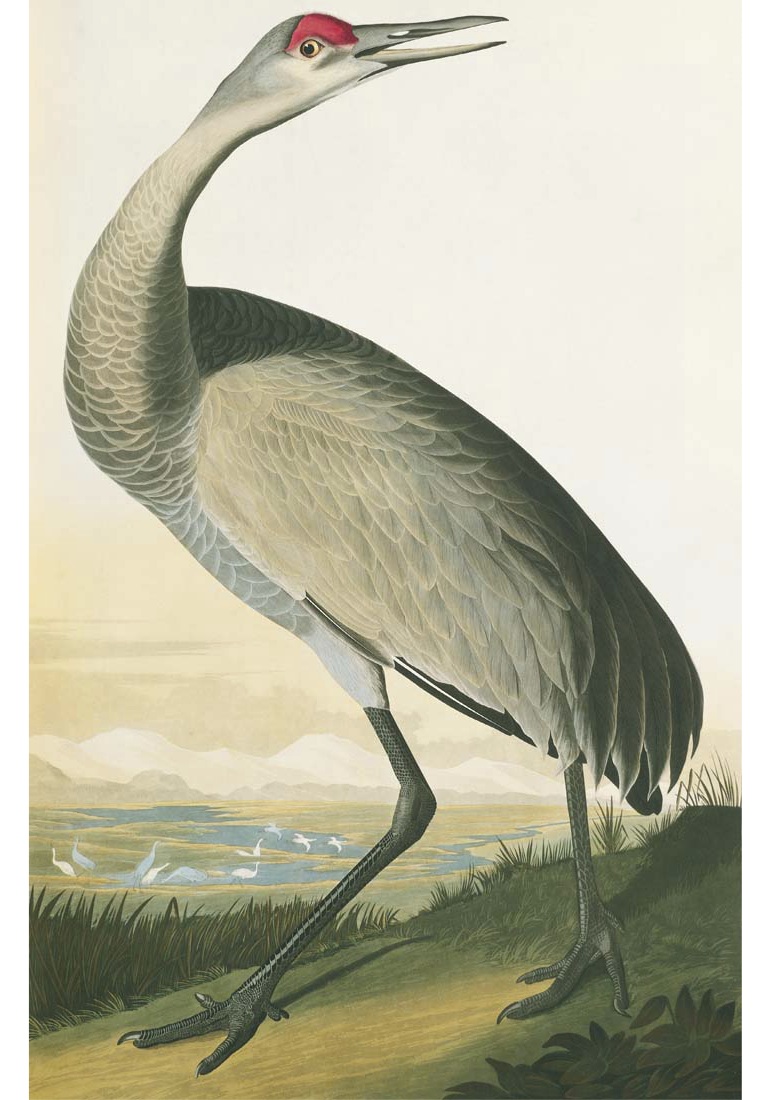

133. Sandhill Crane [Hooping Crane] i

Grus canadensis [Grus Americana]

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Gruidae

(Guard call; Unison call)

Audubon, mistakenly, thought the sandhill crane was the young of the whooping crane. In his account of that species he writes, “The young are considerably more numerous than the old white birds and this circumstance has probably led to the belief among naturalists that the former constitute a distinct species to which the name of Canada Crane, Grus canadensis, has been given. This, however, I hope I shall be able to clear up to your satisfaction. The trachea of this bird confirms my opinion that the Canada Crane (sandhill crane) and Hooping Crane are merely the same species in different states of plumage or, in other words, at different ages. . . . I am convinced that this species does not attain its full size or perfect plumage until it is four or five years old.” Today, of course, we know that Audubon was in error.

There is no question that the sandhill crane was more numerous in early days, particularly throughout the northern prairie states and, in winter, in the Gulf states. It seems to be increasing under protection although limited shooting is allowed locally. Along the eastern seaboard it is merely a casual or accidental wanderer, except in Florida where the local population is augmented in the winter months by migrants from the northern interior.

Great blue herons are sometimes called “cranes,” but herons fly with a rather bowed wingbeat and the neck tucked back to the shoulders; cranes fly with extended neck and an upward flick of the wings.

134. Limpkin [Scolopaceous Courlan] i

Aramus guarauna [Aramus Scolopaceus]

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Aramidae

This odd-looking bird belongs to a monotypic family of which it is the only species. Intermediate between the rails and cranes, it is rather ibis-like in aspect, but can be identified readily by the heavy white spotting throughout its dark brown plumage. Though widely distributed in tropical America from Mexico to Argentina, it is confined in the United States to the central and western parts of the Florida peninsula, only rarely crossing the line into Georgia. Audubon, who used the unlikely name “Scolopaceus Courlan,” wondered why he never saw limpkins as he proceeded westward along the Gulf coast to Texas, inasmuch as the environment seemed suitable, populated by rails and other marsh-loving associates. The reason undoubtedly was the lack of the bird’s basic food, the big greenish Pomacea snails so abundant in many Florida marshes, a fare that it shares with the snail kite. On hummocks or logs where the birds feed, or nearby, there are often great piles of empty snail shells. The piercing cries of limpkins can be heard especially at night and on dark days; a repeated kree-ow, kra-ow, suggesting a small boy being beaten.

135. King Rail [Fresh-water Marsh Hen] i

Rallus elegans

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

(Male advertising call [kek]; Primary contact call [clapper]; Female solicitation call [kek-burr])

Alexander Wilson considered the king rail as merely the adult of the clapper rail and so, apparently, did Thomas Nuttall, another early ornithologist, but Audubon was of a different opinion. He named the bird as a new species, Rallus elegans, the “fresh-water marsh hen” or “great red-breasted rail.” Audubon, who did not get along with Wilson, could not resist taking a crack at him whenever he could. He wrote, “Always unwilling to find fault in so ardent a student of nature as Wilson; I felt mortified when, after having, in the company of my learned friend, the Reverend John Bachman, carefully examined the habits of both species which in form and general appearance are closely allied, I discovered the error. The Rallus elegans is altogether a freshwater bird, while the R. crepitans never removes from the salt water marshes.”

Although this is essentially true, the two species will on occasion be found near each other in the same brackish marshes or where a freshwater marsh is adjacent to a tidal marsh. Hybrids are known. Therefore some systematic ornithologists would lump the two as conspecific, the gray-looking clapper rail being the bird of the coastal salt marshes and the larger, redder king rail being the form of the freshwater marshes. This, the largest of the rails, is widespread but local in the eastern half of the United States from the southern Great Lakes and southern New England south to the Gulf states and Cuba.

136. Clapper Rail [Salt-water Marsh Hen] i

Rallus longirostris [Rallus Crepitans]

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

(Male advertising call; Clapper call; Female kek-burr call)

For hundreds of miles, from Long Island to the Gulf of Mexico, stretch the long beaches, built up of shell and sand, brought from the bottom of the sea by the waves. Behind these barrier islands lie the salt marshes, from one to five miles broad in places. These are the homes of the “Salt Water Marsh Hen.” There might be hundreds in the marsh, but you probably would not see even one if the tide is low, for they are extremely shy, running ratlike through the grass unnoticed. Although they can swim if they must and can fly if they choose, they would rather use their legs. They are easy to locate, however, when the tide comes in and forces them onto the last high spots, or toward sundown when their clattering kek-kek-kek-kek-kek sounds from far and near. Then the marsh seems alive with them, and all night long they answer each other from the sedge.

For many years these palatable fowl, as large as small chickens (fourteen to sixteen inches long), have been favorite gamebirds, hunted up and down the coast. When high storm tides strand them the toll is great, and it is recorded that ten thousand were killed in two days near Atlantic City. Today clapper rails are reduced in number, not alone because of the killing and the egging, but because of a much more potent environmental factor—the drainage of the marshes.

Rallus limicola [Rallus Virginianus]

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

(Grunt call; Female song; Male song)

This small rufous rail, half the size of a king or clapper rail, is a bird of secretive habits. It is heard far more often than seen, especially at dawn when its clattering call or its staccato kidick, kidick announces its presence in the marsh. By compressing its body it can squeeze through the narrowest interstices of the reeds; but if pressed it flies low over the marsh for a brief few feet with legs dangling and drops in again. Its preference is for fresh marshes, but it can also be found in salt marshes along the coast during the winter months.

Although rails have been hunted since colonial days, attrition of their habitat by marsh drainage has affected their populations more than the gun. In fact, rail hunting is a rather specialized sport. Audubon commented that gunners did not pursue this species with any eagerness because of their relative scarcity, but that in Charleston he frequently had seen little strings of them exposed in the market at a very low price. He added that Virginia rails were excellent eating during autumn and winter.

Audubon was impressed with the speed of the Virginia rail. He wrote, “Excepting our little partridge, I know of no small bird so swift of foot as the Virginia Rail. In fact, I doubt if it would be an easy matter for an active man to outstrip one of them on plain ground and to trust to one’s speed for raising one among the thick herbage to which they usually resort.”

Porzana carolina [Rallus Carolinus]

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

(Whinny; Ker-wee; Weep call)

In the days of Gilbert White, the British nature essayist, it was believed that swallows and swifts buried themselves in the mud at the approach of winter. The phenomenon of migration was acknowledged only vaguely. On this theme, Audubon commented, “Superstitious notions and absurd fancies occupied the place of accurate knowledge. . . . Not many years have elapsed since it was supposed by some that the Soras buried themselves in the mud at the approach of cold weather, for the purpose of there spending the winter in a state of torpidity. . . . So rapid has been the progress of ornithology that I should hesitate before asserting that any American, however uncultured, now believes that Rails burrow in the mud.”

Audubon wrote a great deal about the sora, which occurs widely in the marshes of North America. He reported that “the sport of shooting Soras is much akin to that of shooting Clapper Rails. . . . It is not uncommon for an active and expert marksman to kill ten or twelve dozen in a tide. . . . In Virginia, particularly along the shores of James River where the Rail or Sora are in prodigious numbers . . . from twenty to eighty dozen have been killed by three negroes in the short space of three hours.” Soras are still numerous in migration in some marshes, but less so than formerly, not so much because of hunting, which at times has been excessive, but from attrition of habitat due to the massive drainage of marshes for agriculture and the digging of ditches for mosquito control.

139. Yellow Rail [Yellow-breasted Rail] i

Coturnicops noveboracensis [Rallus Noveboracensis]

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

(Song)

This secretive little rail of grassy marshes and wet meadows is widespread but local in Canada and the cooler northern fringe of the U.S. during the summer. How astonishing it is to learn that Audubon was convinced that the yellow rail bred mainly in the South. He wrote, “The Prince of Musignano, who gave a figure of it considered it as an arctic species. This opinion, however, is incorrect, for the Yellow-breasted Rail is a constant resident of the peninsula of the Floridas, as well as in the lower parts of Louisiana, where I have found it at all seasons. . . . On several of the keys, they begin breeding in March. On Sandy Island near Cape Sable, I found several pairs in May, 1832. About New Orleans it commences breeding at the same period.” He added, “No doubt a few stragglers now and then go far north to breed, as I find in the Fauna Boreali-Americana the following note from Mr. Hutchins’ manuscripts: ‘This elegant bird is an inhabitant of the marshes on the coast of Hudson Bay from the middle of May to the end of September. It builds no nest, but lays from ten to sixteen perfectly white eggs among the grass.’” Audubon accepted this but rationalized it when he wrote, “Now this making no nest is to me a convincing proof that the species is not there in its natural place. . . . I saw none in Labrador or Newfoundland.” Audubon was never convinced of this bird’s northern breeding range.

140. Black Rail [Least Water-hen] i

Laterallus jamaicensis [Rallus Jamaicensis]

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

(Song)

The tiny black rail, scarcely more than five inches in length, or about the size of a bobtailed young sparrow, is very difficult to find, even in those areas along the coast where it is known to exist. The best way to see or hear one is to use a tape recorder at night. A good recording of its kiki-doo or kitty-go will bring it out of the marsh literally within arm’s reach. Audubon had no recourse to such sophisticated equipment and apparently never knew the bird in life. His knowledge of the species was altogether derived from Titian Peale, Esq., of Philadelphia who furnished the specimens for the plate, and from Dr. Trudeau who stated that his father shot a considerable number in winter in the vicinity of New Orleans. Rail gunners using dogs to hunt clapper rails and soras sometimes flush black rails, but they are too tiny to be regarded as gamebirds. Their preference is for short grass marshes and salicornia along the coast from Long Island to Florida where they are very local and heard best on dark nights. There is also a very rare and little known inland population. It is not surprising that Audubon never encountered the black rail; very few birders know it well, and to many others it is the “most wanted” species on their list.

Porphyrula martinica [Gallinula Martinica]

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

(Cackle; Cackle; Chip call; Gull-like call)

The purple gallinule with its rich raiment, red beak, and blue frontal shield is much more flamboyant than its more widely distributed relative the common gallinule. As Audubon watched it walking elegantly about, jerking its tail smartly, he was moved to write, “I candidly assure you that I have experienced a thousand times more pleasure while looking at the Purple Gallinule flirting its tail, while gaily moving over the broad leaves of the waterlily, than I have ever done while silently sitting in the corner of a crowded apartment, gazing on the flutterings of gaudy fans and the wavings of flowering plumes.” Lapsing into gallic sentiment, he continues: “What a charming creature, gliding sylph-like over the leaves that cover the lake, with the aid of her lengthened toes, and seeking the mate who, devotedly attached as he is, has absented himself, perhaps in search of some secluded spot in which to place their nest. Now he comes, gracefully dividing the waters of the tranquil pool, his frontal crest glowing with the brightest azure.”

The purple gallinule is a not uncommon local resident in the warmer parts of the southeastern states from South Carolina to Texas. Only rarely does one appear in the north, probably carried by storm winds. Lost strays sometimes come aboard ships at sea or become marooned on islands far from home base. Stragglers have been recorded not only from Newfoundland, but also as far away from home as Tristan d’ Cunha in the South Atlantic, midway between southern Africa and South America.

142. Common Moorhen [Common Gallinule]

Gallinula chloropus

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

(Rapid series of clucks; Yelp; Squawk; Squawk)

Moorhens are henlike on land, ducklike on the water. When walking, they flirt their white undertail coverts smartly; when swimming, they pump their heads back and forth as though it took some effort to propel themselves through the water with their unwebbed feet.

In England, this species was long known as the moorhen, an inappropriate name for a bird that is neither a hen nor an inhabitant of the moors. In the U.S. it went for a long time by the equally unsuitable name of Florida gallinule even though it bred in 37 of the 50 states. Then birders decided that the name Audubon used, common gallinule, was really more appropriate. More recently they have decided to use the original British name.

The common moorhen has a far wider distribution than its gaudy relative the purple gallinule, ranging from southern Canada to Argentina, and also widely across Eurasia and parts of Africa. Audubon was unaware of the extent of its North American range, believing that it seldom went farther north than the Carolinas along the seaboard and not much above Natchez on the Mississippi. Today that certainly is not true.

He wrote, “During my various temporary residences in London, I have often seen the gallinules resort to the grounds in Regency Park, at all hours of the day. They were there in a manner partially domesticated, and walked quite unconcernedly in the meadows. In the middle of the day I could have counted eight or ten pairs in sight.” Today, a century and a half later, one can still see tame moorhens on the lakes and lawns of Regent’s Park.

Fulica americana

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

Coots, so ducklike on the water and so henlike ashore, are related to neither but belong to the same family as the rails. They can be identified readily when swimming on the lakes and bays by their slaty-gray color and very white, unducklike bills. Inasmuch as their feet are not fully webbed, as are those of ducks, but lobed (scalloped toes), they swim with less facility, pumping their heads back and forth with each paddling stroke of the feet. On land they may skulk among the reeds much as rails do or come into the open on lawns and golf courses, where they snip the fresh grass and other vegetation. Although a few coots breed locally along the Atlantic coast, the bulk of the population nests well inland from the Great Lakes and the Mississippi Valley westward. Audubon noted the great numbers on the lakes during migration and in bays along the coast in winter, but he had no knowledge of their principal breeding place.

At times coots congregate in vast numbers in the Gulf States and swim in such close rafts that a hunter in Audubon’s employ once killed eighty with a single shot. Audubon wrote, “They are extremely abundant in the New Orleans markets during the latter part of autumn and in winter when the negros and the poorer classes purchase them to make gumbo. In preparing them for cooking they skin them like rabbits instead of plucking them.”