WOODLAND SPRITES

Vireos and Warblers

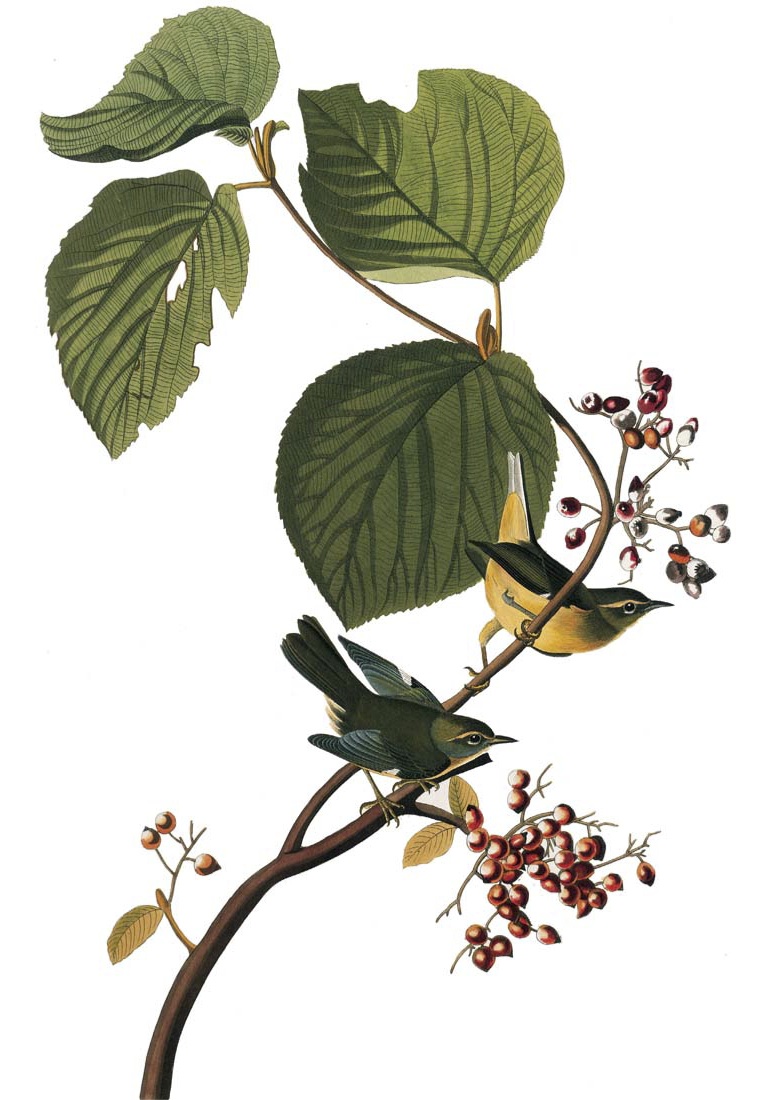

328. White-eyed Vireo [White-eyed Flycatcher or Vireo] i

Vireo griseus [Vireo Noveboracensis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Vireonidae

(Song; Song; Calls)

This, the most southern of our eastern vireos (with the exception of the black-whiskered vireo of Florida), barely reaches southern New England, but seems to be slowly extending its range northward into the Hudson Valley and eastern Massachusetts. On the other hand, Audubon stated that “it is found sparingly in summer as far north as Nova Scotia, and a few were seen by me in Labrador.” He must have mistaken solitary vireos, which have conspicuous white eye-rings, for white-eyes.

This vireo of the southern wood edges, brambles and brush, sings a spirited unvireolike chick!-per-weeo-chick! The sharply accented chick! at the beginning of the song or at the end is the clue to the identity of the singer. Audubon wrote, “This song is . . . emitted with great spirit, and a certain amount of pomposity, which makes it differ materially from that of all other flycatchers.”

Whereas most of the other vireos spend the winter in the tropics, this species and the solitary vireo can be found during that season throughout the lowlands of the seaboard states from the Carolinas to Florida and around the Gulf to Texas and Mexico.

Vireo flavifrons

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Vireonidae

(Song, calls)

This strictly eastern vireo which just barely gets into Canada possibly may be more numerous now than in Audubon’s day. He found it at all times “extremely rare in Louisiana, where I have seen it only during early spring or late in the autumn.” He also wrote that his friend Bachman “has never observed it in South Carolina.” Today, it can be found commonly enough in both of those states if one has a good ear for the nuances of bird voices and can pick it out from the more numerous red-eyes, which also reiterate their phrases from the leafy canopy. Its song is rather like that of the red-eyed vireo, but more musical, lower in pitch and with longer pauses between the phrases. A burry phrase that sounds like three-eight is a clue. Audubon, of course, did not depend on his ears as much as his eyes and we can only wonder whether this vireo with the bright yellow throat was really less numerous than it is today.

There are many factors that could influence the fortunes of a species: Is it cyclic? Has it been affected by land use or forestry in its summer home? Has the environment on its winter range been modified? We are now monitoring populations of birds as well as changes in the environment. But we have no critical baselines with which to compare the past with the present.

330. Solitary Vireo [Solitary Flycatcher] i

Vireo solitarius

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Vireonidae

(Song; Call)

Most birders know this vireo as a not too common migrant, arriving a bit earlier in the spring than the other vireos. While on migration in the eastern states it can be overlooked easily, but in the cool forests of the northern border states and Canada, its sweet, persistent song betrays its presence. Several other vireos have white wing-bars but this one may be known by its snow-white throat, bluish hood, and white spectacles.

Alexander Wilson was the first naturalist to note the “Solitary Flycatcher,” as he called it. In his American Ornithology he implied that it must be very rare, inasmuch as he had seen it on only three occasions. Audubon used that name on his painting but several years later, writing in his octavo Birds of America, he renamed it “solitary vireo,” the name it goes by today (although “blue-headed vireo” was official for many years). Perhaps influenced by Wilson, he had written: “This, dear reader, is one of the scarce birds that visit the United States.” Quite inconsistently, two pages later, he summarized the bird’s status as “rather abundant.” It is possible that this vireo actually had increased. Audubon was informed by his friend, Dr. Bachman, that it was “every year becoming more abundant in South Carolina.”

Although this vireo winters in the Gulf states, Audubon must have confused it with the white-eyed vireo when he wrote that it summered in Louisiana, where he claims to have found its nest and eggs.

Vireo olivaceus

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Vireonidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon regarded this plain little gleaner of the foliage as very abundant. He wrote, “The Red-eyed Vireo is an inhabitant of the whole of our forests.” In 1948, the present author [R.T.P.], wrote in his Birds Over America, “What is the commonest bird in America? Is it the robin? I doubt it. I would not be at all surprised to find that in the eastern states, at least, the red-eyed vireo is more numerous than the robin.” I would not make that statement today. The most numerous bird today must surely be the red-winged blackbird or possibly one of the other icterids.

In recent years, perhaps concurrent with the DDT syndrome, this little vireo of our shade trees and woodlands has taken a noticeable plunge in numbers. DDT is no longer used in the United States, but it might still be a factor in the bird’s survival while on the wintering ground in tropical America, where chlorinated hydrocarbons are still being used widely. We simply do not know. There was a time in the 1940s and later when half of the birds that struck the Washington Monument on September nights were red-eyed vireos, and nearly every woodland breeding bird census testified to their abundance.

Although the red-eye may have declined, it is still a common bird, singing its monotonous phrases from the leafy canopy where it would be overlooked were it not for its insistent voice.

Joseph Mason, Audubon’s young assistant, apparently painted the honey locust and the spider and its web, probably when the two men worked together in Louisiana.

332. Warbling Vireo [Warbling Flycatcher] i

Vireo gilvus [Musicicapa Gilva]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Vireonidae

(Song; Call [mixed])

(Song; Call)

Audubon, who often called vireos “Flycatchers” and sometimes “Greenlets,” knew that this modest songster had a wide range in North America, but he wondered about its travels. “It is surprising,” he wrote, “that this species . . . enters, traverses, and leaves the United States in a manner unknown to anyone.” Although he summarized its range “from Texas to Maine, and in the interior to Columbia River. Abundant. Migratory,” he apparently had his first chance to study its nesting when he took lodgings in Camden, New Jersey, then a little village. In a poplar outside his window he watched a pair as they constructed their nest, laid their eggs, and raised their young; it was one of the most thorough investigations he had ever made into the nesting of a species.

Unlike most other vireos, the warbling vireo does not sing in measured phrases, but has a pleasant warbling song, reminiscent of a purple finch. Audubon wrote, “The male sings from morning to night, so sweetly, so tenderly, with so much mellowness and softness of tone, and yet with notes so low, that one might think he sings only for his beloved.”

One of the best places to look for this species is in the avenues of large shade trees in small towns, where during the last fifty years it seems to have gone through a cycle of relative abundance and scarcity. Today it seems to be increasing again. The elm disease, spraying programs, and other factors may have caused the decline. Birds are often a litmus test of environmental quality.

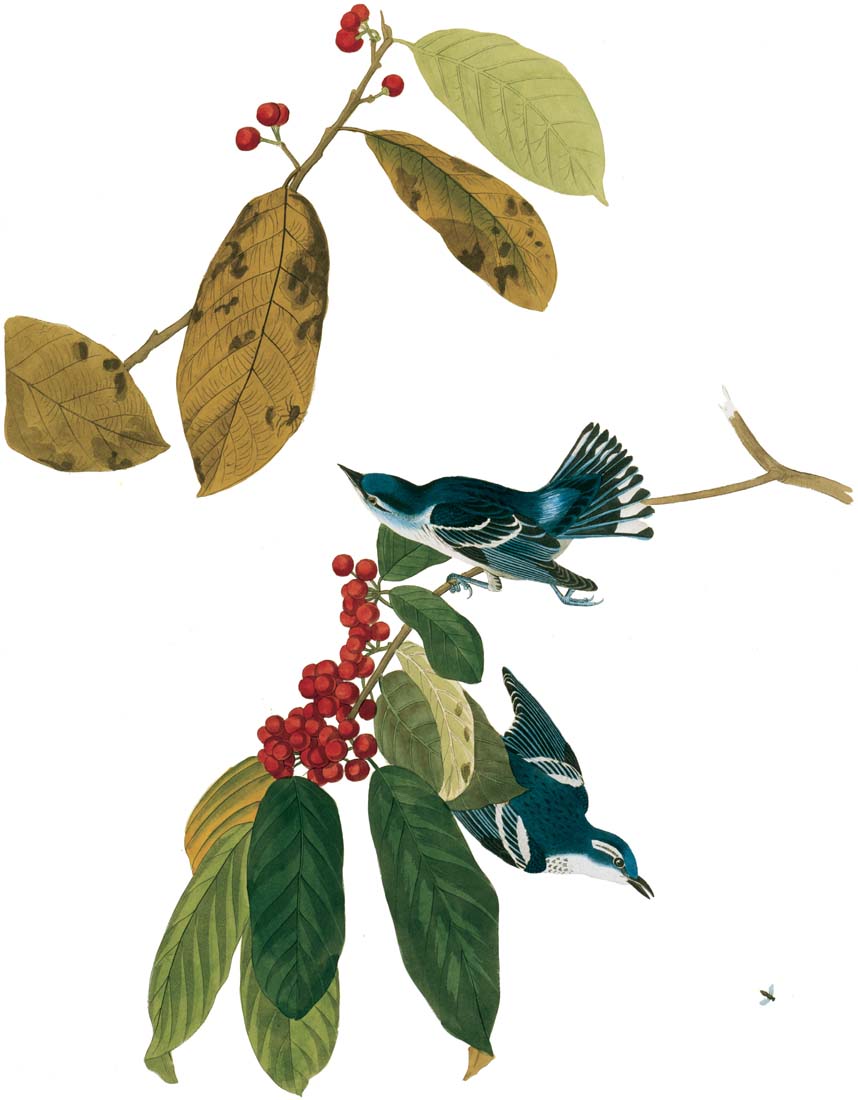

333. Black-and-white Warbler [Black-and-White Creeper] i

Mniotilta varia [Sylvia Varia]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The black-and-white warbler, or “creeper” as Audubon called it, climbs or creeps in nimble fashion about the trunks, branches, and twigs, much like a nuthatch. It does not use its tail as a brace in the manner of a woodpecker or brown creeper. The bird in this composition, shown dangling from the twig of a larch, belies Audubon’s own contention that it “so seldom perches that I do not remember ever seeing it in such a position.”

Its black and white pattern, striped lengthwise, and its striped crown leave no doubt as to this bird’s identity. Males have black throats, which the females lack. Its range is wide in the wooded parts of the continent east of the Great Plains, and its presence is announced during the late spring and early summer by its sibilant song, a thin bisyllabic weesee weesee weesee weesee weesee weesee, suggesting the redstart’s song but higher in pitch. The nest is almost invariably placed on the ground, rarely on the rotted top of a low stump, so it is surprising to read Audubon’s statement in his Ornithological Biography that “in Louisiana, its nest is usually placed in some small hole in a tree.” His contemporary, T. M. Brewer, took issue with this and sent Audubon this note: “This bird, which you speak of as breeding in the hollow of trees, with us always builds its nest on the ground. I say always, because I never knew it to lay anywhere else.”

Protonotaria citrea [Dacnis Protonotarius]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon stated that he had never seen this pretty swamp warbler in “any of our eastern districts” and that “Louisiana seems, in fact, better suited to its habits than any other state on account of its numerous lakes, creeks, and lagoons overshadowed by large trees. It is found flying over the waters of these creeks and lagoons and is seldom seen in the interior of the woods.” Possibly the prothonotary has extended its range since Audubon’s time; it seems unlikely that he overlooked it, since it can be found quite commonly today all through the wooded swamps of the eastern states as far north as southeastern Minnesota, southern Michigan, western New York, and New Jersey.

The song, an emphatic tweet-tweet-tweet-tweet-tweet on one pitch, might easily be overlooked because of its monotonous rhythm. The bird itself flashes like a bright flower against the dark waters of its swampy habitat.

Audubon was quite mistaken when he described the nest as “fixed in the fork of a small twig bending over the water, and constructed of slender grasses, soft moss, and fine fibrous roots.” Actually, the prothonotary warbler is a hole nester, using old woodpecker holes and the natural cavities of trees. Inasmuch as this is the only warbler that nests in this way, he must have assumed that it nested in much the same manner as other warblers. He almost certainly had never seen a nest.

335. Swainson’s Warbler [Brown-headed Worm-eating Warbler] i

Limnothlypis swainsonii

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The Reverend John Bachman of Charleston discovered two species of swamp-loving warblers that had hither-to been unknown. Audubon, who painted and described them, named one after Bachman (see plate 338), the other after William Swainson, of whom he wrote, “To none of my ornithological friends could I assuredly with more propriety have dedicated this species than to him, the excellent and learned author whose name you have seen connected with it—to him who has himself traversed large portions of America, who has added so considerably to the list of known species of birds, and who has enriched the science of ornithology by so many valuable works.”

Unlike a number of other “new species” of warblers that Audubon dedicated to his friends, these two proved to be valid. The others were obscure plumages of species that had already been described.

Swainson’s warbler is not only a very plain “little brown job” but is also a skulker, more likely to be heard than seen. The only distinctive marks are its brown cap and the light eyebrow stripes. Its rich song suggests that of the Louisiana waterthrush. This secretive warbler, confined to the southeastern block of states, is found in two very dissimilar environments—swamps and boggy woodlands, or locally in the Appalachians, in rhododendron-hemlock tangles.

The bird shown in the plate was collected by Bachman on the banks of the Edisto River, near Charleston. The azalea and the butterflies were painted by Maria Martin, who later became Bachman’s second wife.

Helmitheros vermivorus [Dacnis Vermivora]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Flight song; Chip call)

This dull, olive-brown warbler, with the black head stripes that Audubon took such pains to emphasize, nests exclusively in the eastern half of the United States, from Iowa, northern Illinois, and southern New England south to the hilly regions of Missouri and northern Georgia. Within this range it escapes notice in the dry wooded hillsides and shady ravines. Usually, the only clue to its presence is its rapid insect-like song—rather like the trill of a chipping sparrow but thinner and drier. Actually, Audubon was convinced that the “Worm-eating Swamp Warbler,” as he called it, did not sing. He credited it with only a “few weak notes, which do not deserve the name of song.” He apparently was not ear-oriented if we are to judge from his writings. His eye, however, was one of the keenest, and this modest bird did not escape his scrutiny. He summed up its niche very graphically when he wrote: “They are ever amongst the decayed branches of trees or other plants such as are accidentally broken off by the wind, and are there seen searching for insects and caterpillars. They also resort to the ground and turn over the dried leaves in quest of the same kind of food—when disturbed they fly off to some place where withered leaves are seen.”

337. Blue-winged Warbler [Blue-winged Yellow Warbler] i

Vermivora pinus [Dacnis Solitaria]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Type 1 song; Type 2 song; Tzip call)

The “Blue-winged Yellow Swamp-Warbler,” as Audubon called it in his octavo Birds of America, had been described only a few years earlier by his contemporary, Alexander Wilson. The specimens, prettily poised on a hibiscus, were drawn in Louisiana in the spring of 1822. They were obviously migrants on their way from Central America to one of the middle or northern states where the species spends the summer.

The field marks by which the blue-wing can be recognized from the other yellowish warblers are the narrow black mark through the eye and the two white bars on the rather bluish wings. The song, not mentioned by Audubon, is very distinctive—two thin buzzes: beee, bzzzz—the second on a lower pitch, as though the bird were asthmatically exhaling.

This species hybridizes with the closely related but quite dissimilar golden-winged warbler (plate 378) with such frequency that some systematists would lump the two birds as being well-marked races of a single species. The matings result in two interesting looking hybrids that are known, respectively, as Brewster’s and Lawrence’s warblers. During recent years the blue-winged warbler has been extending its range into the habitat of the golden-wing in the northeastern states, and it is believed that eventually the golden-wing may be swamped out by competition—or perhaps genetically through hybridization.

Vermivora bachmanii [Sylvia Bachmanii]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song)

No American bird is more mystifying than this fragile warbler, scarcely more than four inches long. Few living ornithologists have seen it. Discovered by the Reverend John Bachman near Charleston, South Carolina, in 1835, it was described to the world by Audubon. For fifty-three years the little fugitive dropped from sight before it again turned up, this time in Louisiana, but during the succeeding few years, just before the end of the century, hundreds were found. It seemed to be common throughout the river swamps of the South, living in tangled places where trees stood knee-deep in the stagnant pools. Then, before anyone noticed, it again faded away. Very few have been seen during the past forty or fifty years.

Even more curious than the history of the bird itself is that of the plant on which it rests, the Franklinia. Found on the Altamaha River in Georgia by William Bartram, it would be unknown today if the pioneer botanist had not placed in his saddle bag some slips and seeds which he transplanted to his Philadelphia garden. No one has found the tree in a wild state since 1790, for the almost mythical groves along the Altamaha are gone. The tree, however, might survive longer on this earth than the warbler, for trees can be cultivated; warblers cannot. Although Audubon painted the birds in this composition, Maria Martin (who later became Bachman’s second wife) put in the blossoms, drawing them from plants that had come from Philadelphia.

Vermivora peregrina [Sylvia Peregrina]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Alexander Wilson described this plain little warbler from a specimen taken on the banks of the Cumberland River in Tennessee and for this reason this species bears an inappropriate name. Its real home is in the great forests that extend across Canada.

It is curious that Audubon found the bird only three times in his life, twice in Louisiana and once at Key West. It can at times be a very common migrant in the Midwest, where Audubon lived for a while, especially during the latter part of May when its staccato, two-parted song rings from the brushy wayside—ticka ticka ticka ticka, swit, swit, chew-chew-chew-chew-chew!

In spring, the male, with its olive-green back contrasting with its gray head, is distinctive. The underparts and stripe over the eye are whitish. Female and autumn birds are dull greenish, and often quite difficult to separate from some of the other confusing fall warblers. About its migrations and place of breeding, Audubon confessed, “I know nothing.” We now know that it winters in the tropics, ranging from Mexico to Venezuela. A very few linger late on the coast of Texas.

Vermivora celata [Sylvia Celata]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

This dingy little warbler, olive-green above and greenish yellow below, lacks wing bars and other distinctive marks. The “orange” crown which Audubon shows in the lower bird is seldom visible. Many individuals in autumn and winter are decidedly gray. It has a broad range in North America, breeding across Canada to Alaska, and southward in the western states. In winter it is found from the southern states to Guatemala.

Audubon, who obviously knew the bird very well, commented that it was often seen in the company of yellow-rumped and palm warblers while in the southern states, where it passes the winter, and also while in migration to those northern districts where it breeds. He wrote that while in the South, it “is seen in considerable numbers in the orange groves around the plantations, or even in the gardens, especially in East Florida. Like the [palm warbler] it plays about the piazzas, skipping on wing in front of the clapboarded house, in quest of its prey, which it expertly seizes without alighting, or without snapping its bill, except during the disputes that occur among the males, as the spring advances. You find it among the branches of the Pride-of-China, a tree that ornaments the streets of the southern cities and villages, as well as on trees bordering the roads. From these it descends into the similaxes, rose-bushes, and other shrubs, all of which yield it food and shelter.”

Vermivora ruficapilla [Sylvia Rubricapilla]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

(Song; Call)

This is another misnomer, first described by Wilson from a specimen taken near Nashville, Tennessee, where it occurs as a migrant, far from either its winter home in Central America or its summer nesting grounds in the northern fringe of states and Canada. Audubon admitted he knew little about this warbler. He wrote, “I have shot only three or four birds of this species, and these are all I ever met with. I found them in Louisiana and Kentucky. A few specimens belonging to Mr. Titian Peale of Philadelphia, and which he, with his usual kindness, lent me for a few days, to compare their coloring with my drawings and notes, were the only others that I have seen. It is probable he had procured them in Pennsylvania.”

The white eye-ring in connection with the yellow throat is the combination of field marks necessary to identify this small warbler. The head is gray, contrasting with the olive-green of the back. The male may show a dull orange crown patch, but this, like the similar patch on the orange-crowned warbler, may not always be visible. The song, which Audubon never heard, is distinctive, a two-parted affair starting with a series of paired notes—seebit, seebit—and ending with a chipping sparrowlike rattle.

342. Northern Parula Warbler [Blue Yellow-back Warbler] i

Parula americana [Sylvia Americana]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song, call [Mixed])

When Audubon was living in Louisiana, his assistant Joseph Mason shot a parula warbler that Audubon painted under the name “Blue Yellow-back Warbler.” Young Mason drew in the copper iris that Audubon called the “Louisiana Flag,” a flower he had not encountered elsewhere.

Surprisingly, Audubon stated that this bird has no song. He said this also about the prairie warbler, and we wonder again about his hearing, particularly of the high sibilant notes. Indeed this warbler does have a song; a very distinctive trill or rattle that runs up the scale. Perhaps he thought such an effort hardly deserved the term “song.”

The northern parula warbler is a bluish warbler with a yellow throat and breast. Two white wing-bars are conspicuous and a dark band crossing the breast is a useful mark by which to distinguish the male. The female lacks this but can be recognized by her general blue and yellow coloration and white wing-bars.

The parula warbler is widespread in the eastern half of the continent, from the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the Gulf of Mexico, but rather local, preferring humid woodlands where either Usnea moss hangs from the trees (in the North) or Spanish moss (in the South). The nest, very hard to find, is usually hidden toward the tip of a branch in a hanging tuft of moss. Although a few parula warblers winter in Florida, most of them travel to the tropics.

343. Yellow Warbler [Children’s Warbler] i

Dendroica petechia [Silvia Childreni]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song, call; Call)

On several occasions Audubon seemed to have been confused by certain plumages of the yellow warbler and when he painted these two birds at Oakley Plantation in Louisiana he tentatively inscribed his drawing “Louisiana Warbler—Sylvia Ludoviciana.” Later, feeling quite certain that they represented a new species, he crossed out the scientific name and inked in Sylvia Childreni, naming it “Children’s Warbler” in honor of the secretary of the Royal Society, John George Children, who managed his affairs in London. However, he had drawn not a new species but a female and immature yellow warbler. Obviously he became aware of this at a later date, for it was omitted in his octavo Birds of America. However, he did include another drawing of immature yellow warblers which he called “Rathbone’s Wood-Warbler” (plate 344).

To this day immature warblers are frequently identified incorrectly by birdwatchers, even though they have modern texts at their disposal. It is understandable that Audubon, having virtually no books, should be confused by obscure plumages of certain warblers. A modern field guide would have helped him. In A Field Guide to the Birds it is stated unequivocally, “Many warblers have white spots in the tail; this is the only species with yellow spots (with the exception of the female Redstart).” Had Audubon known this simple fact, he would have been spared these two errors.

344. Yellow Warbler [Rathbone Warbler] i

Dendroica petechia [Silvia Rathbonia]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song, call; Call)

Of the thirty-five species of warblers in eastern North America, all but three had been described by Audubon’s time. He named two of them (both discovered by Bachman), the Swainson’s and Bachman’s warblers. But he tried hard. He gave names to ten others that didn’t stick. In this instance, he mistook young yellow warblers for something new (see also “Children’s Warbler,” plate 343). His account is as follows:

“Kind reader, you are now presented with a new and beautiful little species of Warbler, which I have honored with the name of a family that must ever be dear to me. . . . I trust that future naturalists, regardful of the feelings which have guided me in naming this species, will continue to [give] it the name of Rathbone’s Wood-Warbler.

“I met with the species . . . only once, when I procured both the male and the female represented in the plate. They were actively engaged in searching for food amongst the blossoms and leaves of the bignonia.” Audubon did not state where he collected them, but his original pastel was inscribed July 1, 1808, at the “Falls of the Ohio.” Later, in 1825, it was used as a basis for this painting which was inscribed with the same date as the pastel. Curiously, he defines the bird’s range in his Birds of America as “Mississippi—only one pair seen.”

Audubon’s good intentions toward the Rathbones went for nought. The birds he pictured proved to be young yellow warblers.

345. Yellow Warbler [Blue-eyed Yellow Warbler] i

Dendroica petechia [Sylvia Aestiva]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song, call; Call)

This bright little bird, which Audubon named the “Blue-eyed Yellow Warbler” on his colorplate, was later changed in his octavo Birds of America to “Yellow-poll Wood-Warbler.” It is now simply called the “yellow warbler.” Probably the best known of its family to nonbirders, it is identified readily because of its all-yellow appearance, as distinct from the goldfinch which has black wings.

The small bird, which builds a neat felt-lined cup to hold its eggs, is parasitized heavily by the cowbird, which lays its eggs in the nests of other birds, relying on them to hatch the eggs and rear the young. The yellow warbler outwits the cowbird by covering the unwanted egg (and its own) with a new nest floor, then laying again. This strategy was well known to Audubon, who quoted the observations of both Nuttall and Brewer.

The wood-warblers, a New World family, number 114 species, the majority of which are resident in the tropics. Of this bright galaxy, the familiar yellow warbler enjoys by far the most extensive range, breeding from coast to coast and from Hudson Bay to the Gulf states and the West Indies. In the West, its longitudinal range is even greater, extending from Alaska to Peru. Within this vast area there is much variation, both regionally and in the plumages of the sexes and the young. Audubon could never quite sort this out and actually described immature birds as “new” species (see plates 343 and 344).

346. Magnolia Warbler [Black and Yellow Warbler] i

Dendroica magnolia [Sylvia Maculosa]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon drew this immature magnolia warbler in Louisiana on October 20, 1821, when it was in its autumnal migration. Somehow, while he was away from London, during the reproduction of the plates for the first volume of the Elephant Folio, the engraver Havell, or one of his assistants, accidentally substituted this drawing for another, and labeled it “Swainson’s Warbler.” That species is correctly shown on plate 335.

Several years later, in the miniaturized plate in his octavo edition, the engraver included this young magnolia warbler along with the two adults shown on plate 347, but the flowers and large leaves in the original design, probably by George Lehman, were eliminated, making the composition less attractive. Space, of course, was the limiting factor in the small edition.

Immature warblers are a problem to identify in the fall, and many a tyro birdwatcher gives up in despair. The young magnolia warbler, however, is relatively easy because of its tail pattern, well shown by Audubon, a white band crossing the tail midway.

347. Magnolia Warbler [Black and Yellow Warbler] i

Dendroica magnolia [Sylvicola Swainsonia]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon painted this pair of magnolia warblers in the Great Pine Swamp of Pennsylvania in the year 1829, so it is likely that the purple-flowering raspberries were painted by his assistant, George Lehman. The date was August 12, a bit too early for migrants, so it is probable that they were nesting, or had nested in the neighborhood, inasmuch as this essentially Canadian species breeds in the cooler conifer groves of the higher Appalachians as far south as West Virginia.

Audubon’s old name, “Black and Yellow Warbler,” was a good one, far more appropriate than the name it now bears. This species associates with magnolia trees only briefly during migration. It is more typically a bird of the low conifers, at least on its breeding grounds.

Audubon must have encountered a massive movement of magnolia warblers blocked by foul weather when he visited Eastport, Maine, on his way to Labrador. He wrote, “so numerous were those interesting birds, that you might have fancied that an army of them had assembled to take possession of the country. Scarce a leaf was yet expanded, large icicles hung along the rocky shores, and I could not but feel surprised at the hardihood of the little adventurers. If the morning was cold, you might catch them with the hand, and several specimens, procured in that manner by children, were brought to me. . . . By the end of a fortnight the greater part of them had pushed farther north.”

348. Black-throated Blue Warbler [Pine Swamp Warbler] i

Dendroica caerulescens [Sylvia Sphagnosa]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song)

When Audubon painted these warblers in the Great Pine Swamp of Pennsylvania on August 11, 1829, he wrote that this bird “delights in the dark, humid parts of thick underwood, by the sides of small streams. It is very active, seizing much of its prey on wing, as well as among the leaves and bark of low trees.”

Alexander Wilson had previously presented this same bird in his American Ornithology, describing it as a new species, which he called the “Pine Swamp Warbler,” failing to realize that it was simply the female or young of the black-throated blue warbler. Nuttall, in his manual, followed suit and so did Audubon in his Ornithological Biography.

Several years later in his octavo edition, Audubon corrected this, putting the blame on Wilson: “The birds represented in Plate No. 48 of my large edition as Sylvia sphagnosa, are the young of the Black-throated Blue Warbler, the female of which resembles them so much that I looked upon it as a species distinct from the male. I have no doubt that this error originated with Wilson who has been followed by all our writers. Now, however, the Sylvia or Sylvicola sphagnosa of Bonaparte which he altered from Wilson’s S. pusilla, must be erased from our fauna.”

We must remember that Wilson, Audubon, and their contemporaries were at the very frontiers of ornithology, and that such misconceptions were inevitable. In presenting the new plate in the miniaturized version Audubon combined the figure of the upper bird, a female, with that of the male, shown on the columbine in the next plate.

349. Black-throated Blue Warbler i

Dendroica caerulescens [Sylvia Canadensis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song)

The cleancut black-throated blue warbler, with its black throat and sides so neatly set off against the blue-gray of its back and the white of its underparts, was well known to Audubon during migration but he had no experience with it on the breeding grounds; however, he suspected that it bred locally when he visited Maine. In truth he could have found it in the nearby mountains where he had lived in Pennsylvania. He apparently was well acquainted with the female and young but thought they were a different species which he figured under the name of “Pine Swamp Warbler,” Silvia sphagnosa plate 348). He was simply following Alexander Wilson who named this as a separate species and who was followed by Bonaparte and Nuttall in their own manuals. Later, when Audubon prepared the text for his octavo edition, he corrected this error.

The black-throated blue warbler is a widespread resident of the Maritime Provinces and much of New England and from there westward to the northern Great Lakes area and Minnesota. It also extends southward in the higher Appalachians to the Carolinas and northernmost Georgia. Its song, a husky, lazy zur, zur, zur, zreee or beer, beer, beer, beee, is a familiar sound in the undergrowth of deciduous and mixed woodlands throughout that range. It winters mostly in the West Indies, but a very few remain at that season in the southern tip of Florida.

350. Yellow-rumped Warbler [Yellow-crown Warbler] i

Dendroica coronata [Sylvia Coronata]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon called this well-known little bird the Yellow-crowned Wood-Warbler, but the name in common usage until very recently has been “myrtle warbler,” coined no doubt because of its diet of myrtle berries during its winter sojourn along our southern coasts. Many birders have resented the name change, but why was it made? It so happens that the western, yellow-throated form of this bird had long been regarded as a distinct species known as “Audubon’s warbler” (see plate 379). When the Checklist Committee of the American Ornithologists’ Union decided to lump the two forms as conspecific, it was argued that “myrtle warbler” was not a good name because the western population of this bird did not know anything about myrtle berries. So it was decreed that the name should be yellow-rumped warbler, the name that Wilson coined because of its most conspicuous field mark.

As a species this is one of the most numerous warblers in the forests of Canada and Alaska during the summer. This is evidenced by its abundance during the winter months in the southern states.

Audubon observed these birds daily when he spent the winter in Florida, where he reported, “They were very social among themselves, skipped by day along the piazzas, balanced themselves in the air, opposite the sides of the houses, in search of spiders and insects, rambled among the low bushes of the gardens, and often dived among the large cabbage leaves, where they searched for worms and larvae.”

Dendroica cerulea [Sylvia Azurea]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

Audubon was rather vague and equivocal about the beautiful cerulean warbler, which had been seen by very few ornithologists of his day. His first painting of this little bird of the treetops was among the many drawings that were destroyed by rats when he was living in Henderson, Kentucky. He painted the bird again in Louisiana, the upper male shown in this colorplate. The lower bird was added by Havell when he made the engraving and it is believed to have been copied from a drawing by Alexander Wilson, the first ornithologist to describe this species. Later, when Audubon published his octavo edition of the Birds of America, he again reorganized the composition, dropping the figure borrowed from Wilson and substituting the female cerulean warbler shown in the next plate.

The cerulean warbler is basically a bird of the deciduous river valley forests of the Mississippi drainage, ranging from the Great Lakes south to the northern portions of the Gulf states. A disjunct population east of the Appalachians seems to be extending its range locally as far north as Connecticut. As the late William Vogt put it, “Few birds have given more bird students stiff necks than this tiny inhabitant of the remote treetops.”

352. Cerulean Warbler [Blue-green Warbler] i

Dendroica cerulea [Sylvia Rara]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

At the time Audubon painted this bird in Louisiana, in August, 1821, he believed he had discovered a new species. He named it the “Blue-green Warbler, Sylvia Rara.” Later, he realized that it was simply a female or possibly a young male cerulean warbler (see previous plate). In his octavo Birds of America, he combined his original colorplate of the cerulean warbler with this one, dropping the lower cerulean warbler (in the earlier colorplate), which apparently had been copied by Havell from Wilson.

Knowledge of birds was growing rapidly in those days and Audubon’s own revisions were extensive. Critics pointed out certain discrepancies in the text of his Ornithological Biography, which appeared in conjunction with the Elephant Folio, and he was able to make corrections when he published the octavo version several years later.

Audubon indicated on his drawing that the plant was “Spanish Mulberry (Callicarpa americana).”

353. Blackburnian Warbler [Hemlock Warbler] i

Dendroica fusca [Sylvia Parus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call, song)

Here again, Audubon was misled by Wilson into cata-loguing a female warbler as a distinct species—in this case, the female blackburnian warbler, which he called the “Hemlock Warbler.” He wrote: “It is to the persevering industry of Wilson that we are indebted for the discovery of this bird. He has briefly described the male (actually a female) of which he had obtained but a single specimen. Never having met with it until I visited the Great Pine Forest, where that ornithologist found it, I followed his track in my rambles there, and had not spent a week among the gigantic hemlocks which ornament that interesting part of our country, before I procured upwards of twenty specimens. . . .” Audubon never did correct his mistake in his octavo edition which was prepared several years later, even though he correctly added a female to his original plate of the male blackburnian.

Of this supposed “species” he wrote, “The tallest of the hemlock pines are the favorite haunts of this species. It appears first among the highest branches early in May, breeds there, and departs in the beginning of September. Like the Blue Yellow-back Warbler [parula warbler], its station is ever amidst the thickest foliage of the trees, and with as much agility as its diminutive relative, it seeks its food by ascending from one branch to another, examining most carefully the underparts of each leaf as it proceeds.”

Dendroica fusca [Sylvia Blackburnia]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call, song)

Just before Audubon arrived on the scene, during the latter part of the eighteenth century when our nation was new, a specimen of this pretty little wood warbler was sent from New York to England, where it was described and named for a Mrs. Blackburn, who collected stuffed birds and was a patron of the new science of ornithology.

Audubon and Wilson both knew the male blackburnian warbler as a rare transient through the parts of the country where they lived, but neither recognized the female as belonging to the same species (see discussion of plate 353).

This little fiery-throated warbler with its blackish back and broad white wing-patch spends the summer in the pines and other conifers from New England and the Maritime Provinces across wooded Canada to the Rockies. In the higher Appalachians it extends southward to the northernmost tip of Georgia. Elsewhere in the eastern and central parts of the United States, it is seen only in passage to and from its tropical wintering grounds from Costa Rica to Peru. Its song is a thin zip zip zip titi tseeee, with an ending so high and wiry that some ears cannot hear it.

The specimen from which Audubon drew the male was procured near Reading, Pennsylvania, on the banks of the Schuylkill River. The flower is the wild sweet william or spotted phlox. In the miniaturized plate in his octavo edition Audubon correctly added a female, but inexplicably retained his entry on the “Hemlock Warbler” in the same volume.

355. Yellow-throated Warbler [Yellow-throat Warbler] i

Dendroica dominica [Sylvia Pensilis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Call, song; Call)

Handsomely patterned with gray, black, and yellow, this pretty warbler is a summer resident of the southeastern states, barely reaching New Jersey and the Ohio Valley. Formerly, its inland population was found along sycamore-bordered creeks as far north as southern Michigan, but for reasons unknown it no longer occurs there, or is very scarce.

“Happening to shoot several of these birds on a large Chinquapin tree at the edge of a hill close to a swamp,” Audubon recounts, he then put a male on one of its twigs and, with the assistance of Joseph Mason, painted this attractive composition. This occurred when the two men were living and working at Oakley Plantation at Bayou Sara near New Orleans.

The yellow-throated warbler winters throughout Florida, and a few can be found along the coast at that season in adjacent states, but most proceed southward beyond our borders, some as far as Costa Rica. Audubon wrote that it “absents itself from the State of Louisiana only for two months in the year, December and January. When they return at the beginning of February they fill themselves by the thousands into all the cypress woods and cane-breaks, where they are heard singing from the first of March until late autumn.” Their song is a bright series of clear, slurred notes, tee-ew, tew, tew, tew, tew, tew-wi, dropping slightly in pitch and ending with an upward flip.

Dendroica pensylvanica [Sylvia Icterocephala]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

This attractive wood-warbler with its yellow cap and chestnut sides is widely distributed across the northern states and southern Canada, where its bright song, I’m very pleased to meetcha, is often heard from pasture edges and cutover brushlands. It must have been much scarcer in Audubon’s day, for he wrote, “In the beginning of May, 1808, I shot five of these birds, on a very cold morning, near Pottsgrove, in the State of Pennsylvania. There was a slight fall of snow at the time, although the peach and apple trees were already in full bloom. I have never met with a single individual of this species since. . . . Where this species goes to breed I am unable to say, for to my inquiries on the subject I never received any answers which might have led me to the districts resorted to by it. I can only suppose that, if it is at all plentiful in any portion of the United States, it must be far to the northward, as I ransacked the borders of Lake Ontario and those of Lakes Erie and Michigan without meeting it.”

There is a curious contradiction when one reads further in the octavo Birds of America. In the final sentence Audubon states that the species is found “from Texas northward rather common.” Inasmuch as the octavo edition was written several years after his original draft in the Ornithological Biography, Audubon probably had new information, but failed to correct his previous statement.

Dendroica castanea [Sylvia Castanea]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Chip call)

It is rather surprising how little Audubon had to say about some of the migrant warblers. After a rather vague paragraph about his own experiences with this species during migration, he concludes, “The Bay-breasted Warbler, however, has so far eluded my inquiries, that I am unable to give any further account of its habits.”

In summer the bay-breast is essentially a bird of the spruce and fir forests which stretch across Canada from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to the Rockies. Its breeding range only barely dips into the United States in the boreal parts of northern New England, the Adirondacks, and northern Minnesota. In migration, however, it proceeds over the United States on a broad front, crossing the Gulf of Mexico or going around it by way of Texas to its winter home in Panama and northern South America. The male in spring and summer is a dark-looking bird with deep chestnut throat, breast, and sides. By the time it returns in September, it has assumed a modest greenish garb much like the female and young but with just a hint of bay on the sides. Two white wing-bars are a conspicuous feature.

358. Bay-breasted Warbler [Autumnal Warbler] i

Dendroica castanea [Sylvia Autumnalis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Chip call)

In this plate, which Audubon labeled “Autumnal Warbler,” he had apparently drawn two young bay-breasted warblers. These were collected and painted in the Great Pine Swamp near Mauch Chunk, Pennsylvania, on the 20th of August in 1829. They probably represented early fall migrants, as the species has never been known to nest that far south. He wrote, “I have represented a pair of these plain-looking Warblers on a twig of the canoe birch, a tree too well known, from the use to which its bark is applied by the Indians in the construction of their light and beautiful boats, to require any particular description here.”

This “species,” which Audubon named Sylvia Autumnalis, but seemed so vague about, was not mentioned later when he reworked his text in the octavo edition, nor was the plate included. It became simply one of those “confusing fall warblers” which have always been the bane of the birder. The bay-breast and the blackpoll in fall plumage are a perennial field problem. Both are dull birds with whitish wing-bars, but the bay-breast is warmer-hued, less greenish than the blackpoll, and it has blackish, not pale, legs.

359. Blackpoll Warbler [Black-poll Warbler] i

Dendroica striata [Sylvia Striata]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The male blackpoll with its black stripings bears a superficial resemblance to the black-and-white warbler, but its solid black cap and the white cheeks readily identify it. It is not a creeper, however, but flits about like any other wood warbler. The blackpoll is one of the most abundant of the northwoods warblers, favoring the broad ecosystem of stunted spruces and firs that stretches across Canada this side of the tundra. In June, its thin song, a deliberate mechanical zi zi zi zi zi zi zi zi zi on one pitch, first becoming stronger, then diminishing, is a characteristic sound of the bleak landscape.

When Audubon was in Labrador, he and his party had the luck to find the first recorded nest. He wrote, “One fair morning, while several of us were scrambling through one of the thickets of trees, scarcely waist high, my youngest son chanced to scare from her nest a female of the Black-poll Warbler. Reader, just fancy how this raised my spirits. I felt as if the enormous expense of our voyage had been refunded. There, said I, we are the first white men who have seen such a nest.”

The majority of blackpolls making their way to and from northern South America to boreal Canada pour in and out through Florida, but many, particularly in the southward migration, seem to take a shortcut over the water, taking off from the Maritime Provinces, perhaps making landfalls at Cape Hatteras, Bermuda, the West Indies, and other coastal points and islands. Audubon with great intuition suspected this in the case of the blackpoll warbler and certain other species.

360. Pine Warbler [Vigors Warbler] i

Dendroica pinus [Vireo Vigorsii]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

One day in May, 1812, Audubon discovered a small yellow-breasted bird fluttering in the tall grass on a little island in Perkiomen Creek on his farm, Mill Grove, near Valley Forge, Pennsylvania. It perched on the blade-like leaves of the spiderwort on which he drew this portrait. Believing it was something new, he called the diminutive bird “Vigors Warbler,” after Nicholas Vigor, the English naturalist. But here he was mistaken, as he was on several other occasions when he described “new” species. It was an immature pine warbler, a species that had already been described by Wilson and which Audubon came to know very well, particularly during his years in Louisiana. But this individual, away from its usual haunt in the pines, threw him off. It seemed different, and this is quite understandable. It must be remembered that Audubon was pioneering, and that although birds new to science were being described in America, most men were so busy pushing other frontiers that they had little time to watch birds. Today birders have grown legion. The binocular has replaced the gun, and field guides have made the identification of birds quick and accurate. In his octavo Birds of America, written several years later, Audubon made no mention of this “species.”

361. Pine Warbler [Pine Creeping Warbler] i

Dendroica pinus [Sylvia Pinus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon stated its range well when he wrote, “The Pine Creeping Wood-Warbler . . . is met with from Louisiana to Maine, more profusely in the warmer, and more sparingly in the colder regions, breeding wherever pine trees are to be found.” His description of its voice was also felicitous: “The song is monotonous, consisting at times merely of a continued tremulous sound, which may be represented by the letters trr-rr-rr-rr. During the love season, this is changed into a more distinct sound, resembling twe, twe, te, te, te, te, tee. It sings at all hours of the day, even in the heat of summer noon, when the woodland songsters are usually silent.” Other writers have compared the song aptly to that of a chipping sparrow—a trill on one pitch, but slower and more musical.

The combination of yellow underparts and white wing-bars, without other conspicuous field marks, usually distinguishes the pine warbler. The sides of the breast are dimly streaked and the back is unstreaked; in brief, a rather plain, undistinguished looking warbler. Some females and young, especially in the fall, are very obscure, and it has been remarked that “a trayful of specimens looks like a catchall for the museum’s ratty, discarded warbler skins.”

Hardier than most of its kin, the pine warbler winters widely in the southern states and can occasionally be found in that season as far north as New Jersey.

Dendroica discolor [Sylvia Discolor]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song, call)

Audubon, when he painted this delicate warbler in Louisiana, chose to portray it, rather inappropriately, on a sedge which was drawn by his assistant, Joseph Mason. The prairie warbler favors dry, bushy slashings and semi-open pasturelands, particularly where there is a new growth of oak or pine; however, along the coast of Florida it is addicted to mangroves.

Audubon surprisingly stated that the bird has no song: “At least I have never heard from it.” Actually the prairie warbler is a persistent singer with a very distinctive song, a thin zee-zee-zee-zee-zee-zee-zee-zee, ascending the scale. It is obvious that he must have seen the bird in many parts of the eastern United States; but how he could have avoided hearing it is a puzzle. Perhaps his memory lapsed on this point or perhaps his ears may not have been sensitive enough to catch the high registry.

Prairie warblers can be identified by the yellow underparts with black stripings confined to the sides. Two black face marks—one through the eye and one below it—are the critical field marks. In his drawing Audubon failed to show the distinctive chestnut markings on the back of the male. This species wags its tail much like a palm warbler, the only other common warbler to have this behavioral trait.

363. Palm Warbler [Yellow Red-poll Warbler] i

Dendroica palmarum [Sylvia Petechia]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song)

(Call, song)

The palm warbler is a bird of palms and other subtropical habitats only during the winter months, when it is abundant in the lowlands of the southeast and the Caribbean area. It is recognized readily—even in its relatively obscure winter plumage, when it lacks the deep chestnut of its cap—by its ground-loving habits and the constant bobbing of the tail.

During the summer it prefers the more austere environment of the Canadian northwoods, especially the wooded borders of bogs and muskegs, where its weak repetitious song, zhe-zhe-zhe-zhe-zhe-zhe, will pinpoint the territorial male. Audubon was at first under the impression that the two subspecies of the palm warbler—the strongly yellowish eastern race and the less yellowish race of the interior—were two distinct species. Later he wrote, “I most willingly acknowledge the error under which I labored many years in believing that this species and the Sylvia palmarum of Bonaparte, are distinct from each other.” While in Charleston in the winter and spring of 1833–34, his friend John Bachman convinced him of this, after examining a great many specimens in different stages of plumage.

There was a time, not so long ago, when eastern birders made a point of listing “yellow palm warblers” as distinct from “western palms.” Today most field birders ignore subspecies, acknowledging that the problem should remain the province of the museum curator who deals with “birds in hand.”

Dendroica palmarum [Sylvia Palmarum]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song)

(Call, song)

Whereas Audubon treated the birds on this and the previous plate as two distinct species, he changed his mind after discussing things with his astute friend, John Bachman. Thus, when he rewrote the text for his octavo edition, he lumped them as conspecific. In his miniaturized version of the drawings he cannibalized the lower bird from the previous plate and combined it with the two birds shown here.

Although on this plate Audubon inscribed “Palm Warbler,” the name by which the species still goes today, he preferred the other name. He wrote, “The Yellow Red-poll Warbler is extremely abundant in the Southern States, from the beginning of November to the first of April, when it migrates northward. It is one of the most common birds in the Floridas, during the winter, especially along the coasts, where they are fond of the orchards and natural woods of orange trees. In Georgia and South Carolina, they are also very abundant, and are to be seen gambolling, in company with the Yellow-rumped Warbler, on the trees that ornament the streets of the cities and villages, or those of the planter’s yard. They approach the piazzas and enter the gardens, in search of insects, on which they feed principally on the wing, now and then securing some by moving slowly along the branches. It never removes from one spot to another, without uttering a sharp twit and vibrating its tail in the manner of the Wagtails of Europe, though less frequently.”

365. Ovenbird [Golden-crowned Thrush] i

Seiurus aurocapillus [Turdus Aurocapillus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

This aberrant warbler has the look of a small thrush and indeed, Audubon thought it was one. He commented,“The nest is so like an oven, that the children in many places call this species the ‘Ovenbird.’” Usage has won out and today the bird is known officially by that name. It walks—rather than hops—on pale pinkish legs over the leafy woodland floor and along mossy logs. Although it suggests a small thrush because of its spotted underparts, the black-bordered orange crown is distinctive.

A dozen ovenbirds are heard for every one seen. Its emphatic chant, teacher, teacher, teacher, Teacher, Teacher, TEACHER!, heard in a rising crescendo, is a typical sound of the summer woodlands in many parts of the eastern United States as well as in wooded Canada north to Newfoundland and James Bay. A few winter in Florida and along the Gulf coast, but most invade the forests of the tropics, some of them proceeding as far as northern South America where antbirds and other gleaners of the jungle floor offer stiff competition.

In addition to its well-known teacher chant, the ovenbird has another song which sometimes can be heard toward evening or even at night, an ecstatic tumble of notes that puzzled Thoreau, who often heard it at Walden Pond. He called it “the night warbler.” The singer may wait as much as an hour before it repeats this performance, which may end with the familiar teacher, teacher, a clue to the bird’s identity.

366. Louisiana Waterthrush [Louisiana Water Thrush] i

Seiurus motacilla [Turdus Aquaticus]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Song; Call)

The two waterthrushes, the northern and the Louisiana, are so much alike in general appearance that they often confound even the expert birder unless they sing, so it is not surprising that Audubon was confused. In his Elephant Folio he correctly figured both species, naming this one “Louisiana Water Thrush” and the one shown on plate 435 as “Common Water Thrush.” However, several years later when he prepared his octavo edition he had a change of mind and lumped the two. In preparing his miniaturized illustration, he excised the “Common” or northern waterthrush from the composite plate (no. 435) and joined it with the Louisiana waterthrush shown here, labeling one a male, the other a female, and giving them a new name, “Aquatic Wood Wagtail.” This, of course, briefly impeded the progress of ornithology, but eventually other authors put things straight again.

The Louisiana waterthrush is the one that haunts the brooks, ravines, and wooded swamps from the southern Great Lakes to the Gulf states. There in the damp forests its wild ringing song can be heard; three clear, slurred whistles, followed by a jumble of musical twittering. In the East, the Louisiana waterthrush can be readily separated from the northern waterthrush by its white eyebrow stripe and white underparts (the northern is buffy yellow). Not so farther west, northern waterthrushes have white eyebrow stripes.

The northern waterthrush is basically Canadian during the summer months, slightly overlapping the range of the Louisiana waterthrush in southern New England and in the central Appalachians.

Oporonornis formosus [Sylvia Formosa]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Although Audubon described the range of this secretive warbler as the Valley of the Mississippi and Kentucky, it is more widespread than that, inhabiting moist woodland thickets and glades from the Gulf states north to southern Wisconsin, northern Ohio, and the lower Hudson Valley. The winter is spent in Mexico and Central America.

The song of the Kentucky is very suggestive of the rolling chant of the Carolina wren and might be described as tory-tory-tory-tory. To Audubon’s ears it sounded like tweedle-tweedle-tweedle. For every Kentucky warbler seen, at least ten are heard. Skulking furtively in the moist undergrowth, it is hard to glimpse, but when it allows a clear view it suggests the more familiar yellowthroat. Its distinguishing marks are the black sideburns or whiskers and the yellow spectacles. It nests on the ground, attaching a well-constructed little basket to the stems of weeds and shrubbery.

Audubon inscribed his original colorplate with the name it bears today, but he changed it later in his octavo Birds of America to “Kentucky Flycatching Warbler.”

Oporornis agilis [Sylvia Agilis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song)

The Connecticut warbler is another misnamed bird. It was described by Alexander Wilson, who wrote, “This is a new species, first discovered in Connecticut and twice since met with in the neighborhood of Philadelphia.”

Actually, it is basically a bird of the Canadian zone, breeding near the upper Great Lakes and from there to the north and northwest into Canada. Lucky is the birder who sees one in Connecticut; the best time is September, when a few migrating individuals drift toward the coast on their way to Central and South America. It differs from the very similar mourning warbler in having a distinct white eye-ring.

Audubon was lucky enough to encounter this secretive skulker on two or three occasions. He wrote, “I procured the pair represented in the plate on a fine evening nearly at sunset, at the end of August, on the banks of the Delaware River, in New Jersey, a few miles below Camden. When I first observed them, they were hopping and skipping from one low bush to another, and among the tall reeds of the marsh, emitting an oft-repeated tweet at every move. I followed them for about a hundred yards, when, watching a fair opportunity, I shot both at once.” He outlined them by candlelight that evening, and finished the drawing next morning. The actual date inscribed on the drawing is not August but September 22 (1829)—a more likely date for this species.

The plant on which they are portrayed by George Lehman is soapwort, a kind of gentian.

369. Common Yellowthroat [Maryland Yellow-throat] i

Geothlypis trichas [Sylvia Trichas]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Audubon designated this aberrant member of the wood warbler family as the “Maryland Yellow-throat,” a name that was changed by ornithologists only recently. Acting more like a wren than a warbler, it hops about in the scrubby vegetation of swamps, stream edges, and other wet places, singing its cheerful song, a rapid, well-enunciated witch-ity, witch-ity, witch-ity, witch. The male, as Audubon’s illustration shows, is very distinctive with a black mask above its yellow throat. The female lacks this distinctive black domino.

Audubon wrote: “The notes of this little bird render it more conspicuous than most of its genus. . . . In walking along the briary ranges of the fences, [one] is almost necessarily brought to listen to its ‘whi-ti-ti-tee,’ repeated three or four times every five or six minutes. . . . Although timid, it seldom flies far off at the approach of man, but usually dives into the thickest parts of its favorite bushes and high grass and renews its little song when only a few feet distant.”

Yellowthroats are found widely from southern Mexico throughout the United States to southeastern Alaska, the Canadian prairie provinces, and Labrador, and have been split by taxonomists into a number of subtly different subspecies. They spend the winter in the Gulf states and north along the coast to North Carolina. Occasionally, a straggler can be found during the cold months as far north as southern New England.

370. Common Yellowthroat [Roscoe’s Yellow-throat] i

Geothlypis trichas [Sylvia Rosco]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

When Audubon made this drawing in 1821, his inscription at the bottom of the plate identified the birds as “Louisiana Yellow-throat.” Under the impression that it was a new species, he changed the name to “Roscoe’s Yellow-throat,” in honor of William Roscoe, an English historian. But later, when he published his octavo Birds of America, he had second thoughts. Recomposing the plate of the “Maryland Yellow-throat,” he added this figure which he then presumed to be an immature male of the common species.

A number of races or subspecies of yellowthroats are now known throughout North America and it is little wonder that Audubon, pioneering the continent, was confused. Later he described still another form from a California specimen obtained from Mr. Townsend, naming it “Delafield’s Ground Warbler,” in honor of Colonel Delafield, president of the Lyceum of Natural History in New York. He said that it so much resembles the “Maryland Yellow-throat” that one might easily confuse the two species. Obviously it was not a new species and later it was designated as a subspecies by the Checklist Committee of the American Ornithologists’ Union.

Icteria virens [Icteria Viridis]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Calls)

The versatile chat has been called an acrobat, a clown, and a ventriloquist. Its strange puzzling calls come from the thickets while the singer remains hidden—clucks, mews, caws, coos, and whistles that would do credit to a mockingbird. However, the chat’s repertoire is more limited than that of a mocker, with longer pauses between the phrases.

The act that caps the climax of the show is the flight song, when, revealing itself at last, the bird ascends with flopping wings and dangling legs, singing wildly, and parachutes back to the briar patch. Audubon faithfully records the clowning grotesquerie of the flight song, while he shows below a female brooding amid a bower of sweet-briar roses.

Systematists disagree as to how the chat should be classified. For want of better solution they have placed it with the warblers, even though it is 7½ inches long, half again as large as the general run of warblers. However, it acts more like one of the mimic thrushes (the family of birds that includes the catbird, brown thrasher, and mockingbird). It likes the same kind of brushy tangles they do, has the same loose-jointed actions, sings and mimics like one, sings on moonlit nights as they often do, and, of course, its flight song suggests that of a mockingbird. Can it be that living as neighbors in the same environment—the same catbriar tangles—produces a similar personality?

372. Hooded Warbler [Selby’s Flycatcher] i

Wilsonia Citrina [Muscicapa Selbii]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

When Audubon was at the plantation of James Pirrie in Louisiana during the summer of 1821, he painted this rather nondescript warbler, which he thought was a new species. The notes on his original drawing indicated that he first called it “Louisiana Flycatcher” and he gave it the scientific name Muscicapa ludoviciana. Later he renamed it “Selby’s Flycatcher” in honor of a British ornithologist, Prideaux John Selby. Actually, it was an immature hooded warbler. Only a month later he drew the hooded warblers that appear on plate CXXXX of the Havell series (see next plate). Somehow he did not make the connection between this immature bird and the adults he drew subsequently. Hooded warblers are common in the wooded countryside of the southern states and Audubon undoubtedly knew them well; but inasmuch as females and immatures are variable he seems not to have recognized the identity of the individual portrayed here. This is understandable. He was a pioneer, sorting things out in a day when ornithology was a primitive science and knowledgeable bird-watchers were far rarer than the birds they pursued. Determining the exact identity of some of Audubon’s birds, especially immatures, has demanded a degree of detective work and intuition. In fact, several have never been satisfactorily identified.

Wilsonia citrina [Sylvia Mitrata]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The hooded warbler, which actually wears a cowl rather than a hood, sings brightly in the more extensive tracts of woods throughout the east except in the northernmost states and in peninsular Florida. Audubon sets the stage for this handsome bird: “The tall trees are garlanded with climbing plants which have entwined their slender stems around them, creeping up the crevices of the deeply furrowed bark, and vying with each other in throwing forth the most graceful festoons, to break the straight lines of the trunks which support them; while here and there from the taller branches, numberless grape-vines hang in waving clusters, or stretch across from tree to tree. The underwood shoots out its branches, as if jealous of the noble growth of the larger stems, and each flowering shrub or plant displays its blossoms, to tempt the stranger to rest awhile, and enjoy the beauty of their tints, or refresh his nerves with their rich colors. Reader, add to this scene the pure waters of a rivulet, and you may have an idea of the places in which you will find the Hooded Warbler.”

This lovely species leaves the United States to spend the winter from Mexico and the West Indies to Panama.

Audubon vacillated a great deal about his nomenclature, both vernacular and scientific, often changing names between his Ornithological Biography and his revised octavo edition. In this case, his hooded warbler, Sylvia Mitrata, became “Hooded Flycatching-Warbler, Myiodioctes Mitrata.”

374. Wilson’s Warbler [Green Black-capt Flycatcher] i

Wilsonia pusilla [Muscicapa Pusilla]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Wilson had the jump on Audubon by about 20 years, therefore he was the first to describe and name ten species of warblers that were new to science. This was one of them. There seemed to be some equivocation at that time as to whether some of these little birds were warblers or flycatchers, and Audubon, in his Elephant Folio, called this one the “Green Black-capt Flycatching Warbler.” He obviously knew the bird better than Wilson, who had met with it only in Delaware and New Jersey, supposing it to be an inhabitant of the southern states. Audubon knew better. He found this little yellowish warbler with the diagnostic black cap not rare in Maine and stated that it became “more abundant the farther north we proceed. I found it in Labrador and all the intermediate districts.” Wilson’s warbler does indeed occur in the southern states, but mainly in migration. Although a few may winter along the Gulf coast, most leave for Mexico and Central America.

The habitat of Wilson’s warbler, when in Canada, is not evergreen forest, but thickets along wooded streams, tangles of low shrubs, willows and alders. There it sings a rapid little chatter of no distinction. The female, lacking the black cap, looks a bit like a dull female yellow warbler, except for the absence of yellow tail spots. In the West, Wilson’s warbler enjoys a broad breeding range, from northern Alaska south through the high mountains to the southwestern states.

375. Canada Warbler [Bonaparte Flycatcher] i

Wilsonia canadensis [Sylvia Pardalina]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

When Audubon first drew this little bird, poised on the fruiting branch of a magnolia, he inscribed it as a “Cypress Swamp Flycatcher,” then changed it to “Bonaparte Flycatcher,” in honor of Prince Charles-Lucien Bonaparte. Later, when he published his octavo Birds of America, he again changed the name, to “Bonaparte’s Flycatching Warbler.” There is an evolution in names, and although some stick, no matter how inappropriate, others change. Many birds portrayed by Audubon are known by names that are quite different today. Usage has dictated some; others have been modified as their relationships were clarified. Thus, in due time, it was decided that the present species was a warbler, not a flycatcher, and not a new species as Audubon had thought, but actually a young female Canada warbler, a species that Audubon was to paint again eight years later under the name “Canada Flycatcher” (plate 376).

If the author of every new bird book decided to change names to suit himself, all would be chaos. Hence the scientific organization known as the American Ornithologists’ Union (A.O.U.) has set up a checklist committee to pass on questions of nomenclature. The scientific names they decide on become official. As for English names, the checklist committee of the American Birding Association (A.B.A.) has standardized those we use today.

Wilsonia canadensis [Sylvia Pardalina]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

Well-named, the Canada warbler lives in the undergrowth and shady thickets throughout the trans-Canadian forest. It is also a summer resident in similar terrain in much of New England and New York State and down the higher Appalachian ridges as far as the northern tip of Georgia. A combination of gray and yellow, with a necklace of short black stripes, identifies the male; in the females and young, the necklace is fainter or lacking. Its song is an irregular burst, somewhere between staccato and singsong, hence hard to describe.

Audubon wrote, “I first became acquainted with the Canada Flycatcher” (as he called it in his octavo edition) “in the Great Pine Forest, while in company with that excellent woodsman, Jediah Irish, and I have since ascertained that it gives a decided preference to mountainous places, thickly covered with almost impenetrable undergrowths of tangled shrubbery. I found it breeding in the Pine Forest, and have followed it through Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Newfoundland and the country of Labrador, in every portion of which, suited to its retired habits, it brings forth its broods in peaceful security.”

In his octavo edition Audubon defends his judgment that his “Bonaparte Flycatcher” (plate 375) is a valid species quite distinct from the Canada warbler or “Canada Flycatcher” shown here. He was in error.

Setophaga ruticilla [Muscicapa Ruticilla]

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

(Song; Call)

The redstart, one of the most flamboyant of the wood warbler family, is almost butterfly-like when it spreads its wings and tail. If it is a male, it will display orange patches; if a female, yellow patches. Its bright song, a bi-syllabled Teetsa, teetsa, teetsa, teet, or its alternate Tsee-tsee-tsee-tsee-tsea, calls attention to this brightly-colored mite as it flits about the spring greenery. It is primarily a bird of the deciduous forest, especially second growth, ranging in summer through much of eastern and central North America from Manitoba and the Gulf of St. Lawrence south to the northern edge of the Gulf states. The winter months are spent in the West Indies and in the Central and South American tropics.

Audubon showed this pair at a wasps’ nest and, in explanation, wrote: “I have looked for several minutes at a time on the ineffectual attacks which this bird makes on the wasps while busily occupied about their own nests. The bird approaches and snaps at them, but in vain, for the wasp elevating its abdomen protrudes its sting, which prevents its being seized. The male bird is represented in this plate in that posture.”

In Audubon’s original painting, the female at the top was painted without a branch; the branch was added later by Havell when he made the engraving.

Clockwise from top center:

Vermivora chrysoptera [Sylvia Chrysoptera]

(Type 1 Song; Alternate song)

Cape May Warbler i

Dendroica tigrina [Sylvia Maritima]

(Song; Sip call)

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

The golden-winged warbler (upper two) and the blue-winged warbler (plate 337), although so dissimilar in appearance, interbreed freely, producing hybrids known as Brewster’s and Lawrence’s warblers. Recently the blue-winged warbler has been expanding in the Northeast, gradually displacing the golden-winged warbler and perhaps swamping it out genetically.

The Cape May warbler (lower two) has had a very interesting history and has been called “the bird that made Cape May famous.” It was first described in 1789 by Linnaeus’s successor, Gmelin, who based his description on a bird that flew aboard a vessel off Jamaica and was described by George Edwards. Gmelin gave it the scientific name tigrina (little tiger), the name it bears today. Alexander Wilson, unaware of this, described the species from an adult male collected by his friend George Ord, in a maple swamp in Cape May County, New Jersey, in May 1811. Although he never saw it in life, nor obtained another, he bestowed upon it the inappropriate name of Cape May warbler. Audubon never saw one either. His specimens were collected by Edward Harris near Philadelphia. Curiously, it was 109 years before another was recorded at Cape May, spotted by Dr. Witmer Stone in a shade tree on September 4, 1920.

Cape May warblers winter in the West Indies and breed in the boreal forests of Canada, and seem to build up their numbers when there are spruce budworm outbreaks. It is possible that they have increased a great deal in recent times.

From top to bottom:

379. Yellow-rumped Warbler [Audubon’s Warbler] i

Dendroica coronata [Sylvia Auduboni]

(Song; Call)

Hermit Warbler i

Dendroica occidentalis [Sylvia Occidentalis]

(Song; Call)

Black-throated Gray Warbler i

Dendroica nigrescens [Sylvia Nigrescens]

(Song; Call)

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

The yellow-rumped warblers (male and female) at the top are of the western yellow-throated race, formerly known as Audubon’s warbler. When it was decided that the Audubon and the myrtle warblers (plate 350) were conspecific, the old name yellow-rumped warbler was restored.

The two birds in the center (female left, male right) are hermit warblers. This species, like the previous one, is a resident of the cooler fir forests of the Pacific states. It suggests a modified version of the black-throated green warbler which is found in similar conifers in the East.

The lower pair are black-throated gray warblers, another western species. This species, however, is not a bird of the cool fir forests but inhabits dry oak slopes, piñons, and junipers. All three species shown here have been known to stray accidentally to the Atlantic states. In fact, the black-throated gray warbler is recorded somewhere in the East nearly every year.

The specimens from which Audubon drew these figures were sent to him by Dr. John Townsend, who collected them while on his Columbia River expedition.

From top to bottom:

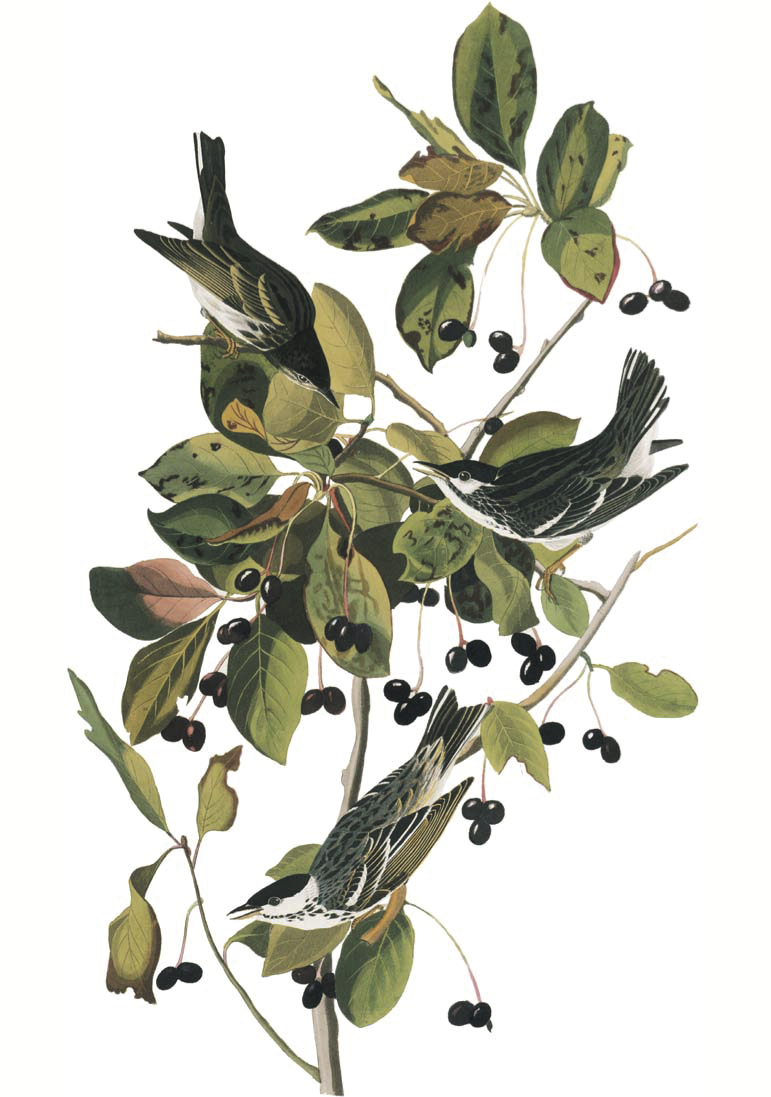

380. Black-throated Green Warbler i

Dendroica virens [Sylvia Virens]

(Type 1 song; Type 2 song; Call)

Blackburnian Warbler i

Dendroica fusca [Sylvia Blackburniae]

(Song; Call, song)

MacGillivray’s Warbler [Mourning Warbler] i

Oporornis tolmiei [Sylvia Philadelphia]

(Song; Call)

Order: Passeriformes

Family: Emberizidae

The original painting for this plate, included five species of warblers drawn by Audubon and his son, John, when they were in Charleston during the winter of 1836–37. The golden-winged and Cape May warblers were removed from the original composition and reproduced separately (plate 378).