CHAPTER TWO

The Old Order

Contact between the Mediterranean and Temperate Europe was no new phenomenon. As early as the neolithic in the fifth-fourth millennium spondylus shells, probably from the Aegean, were circulating among the early farming communities of the Danube valley. The diffusion of the techniques of agriculture can be taken as an analogy for later diffusion patterns. Agriculture could not be simply transplanted from the Near East to central Europe—it required modification, new and hardier breeds of animals and plants, new domesticated species, and new methods of farming. In the same way, urbanism had to adapt to central Europe a few millennia later.

It was, however, the advent of bronze metallurgy that started the symbiotic relationship between the two areas. Copper, and more especially tin, are of localised occurrence, and areas such as the Aegean or Scandinavia were forced to rely on long-distance trade to obtain their metal supplies. Unfortunately, even using modern methods of analysis for the identification of trace elements, so complex is the pattern caused by the variability of the original ores even from a single mine, and of the processing of the metal, alloying, and reuse, that only rarely is it possible to identify the source of the metal outside its areas of origin. So, although we can be fairly sure metals from the north were reaching the east Mediterranean, the precise routes and the mechanisms of the trade still elude us.

Doubtless this trade, both local and interregional, was one of the causes behind the everincreasing input of labour and destruction of wealth associated with the burial of specific individuals. At the end of the third millennium in central Europe bodies might be accompanied by an elaborate pot or one or two metal ornaments, and be buried under a small round barrow. Early in the following millennium, for instance at Leubingen in East Germany, an elaborate timber structure under an ostentatious barrow might include axes and halberds, gold pins, even possibly human sacrifice. By the thirteenth-twelfth century wagons accompanied the wealthiest, like the pyre burial of Hart-an-der Alz in Bavaria with its rich collection of bronze vessels, some possibly of North Italian origin; or the warrior at Čaka in Slovakia, interred with a corselet of bronze—a display of funerary wealth that would not reappear again in central and western Europe until the beginning of the Iron Age in the seventh century BC.

Other goods and materials were being traded. Amber from the Baltic is one of the easiest to identify archaeologically, passing down the river routes of the Elbe and Oder, and reaching the Aegean, while in return from central Europe bronze reached Scandinavia in increasing quantities. Salt was also being produced at Halle on the Saale in East Germany—probably the basis of the wealth of the Leubingen burial. With this centralisation of surplus came greater specialisation in craft products—gold ornaments and cups, beads of faience, jet and shale, which too are found in the wealthier burials.

In Temperate Europe this centralisation of wealth mainly found expression in archaeological terms in burials, hoards (some of which were deliberately deposited rather than accidentally not recovered), or more rarely in ceremonial monuments such as Stonehenge. But in one area of Europe, the Aegean, this centralisation of wealth and power took on a more extreme version, in the palaces of Minoan Crete and Mycenaean Greece. What caused this lies outside the realms of this book, but clearly trade and the proximity of the great irrigation civilisations of Mesopotamia, Turkey and Egypt were contributory factors.

The palaces acted as centralised stores for grain, olive oil and other agricultural surplus, and this in turn was used to support specialists of many kinds, indeed the palaces may also have been able to control production of both prestige and many utilitarian goods. Potters were producing fine ceramics of a kind which had no equal in the rest of Europe or even the east Mediterranean. Mycenaean pottery appears in Egypt and the Levant in historically dated contexts, which allows us to fix fairly precise dates for the Mycenaean world up to about 1100 BC. Metalsmiths were working bronze, silver and gold, inlaying bronze dagger blades with hunting scenes. Architecture developed with ashlar construction for both the palace buildings and the collective tholos tombs, while around the Minoan palaces and Mycenaean citadels there clustered stone-built houses, agglomerations of population which we might well describe as urban. And to run the whole system there appeared a class of bureaucrats who inscribed their accounts on tablets of clay, in Greek.

All this is evidence for a concentration of power and a level of specialisation unparalleled outside the Near East. Some of the specialisms (ashlar building, writing) were unique in Europe to the Mycenaean world, and the surrounding societies to the north and west were incapable of emulating the production of the luxury goods. But Mycenaean Greece did not hold a monopoly of innovation, and in one sphere at least it was surpassed, in the production of weapons. The major innovation in fighting in the thirteenth-twelfth centuries BC was the flangehilted sword. Various early varieties are known, with different shapes of hilts, the best known being the Hemigkofen and the Erbenheim varieties. Partly these swords owe their appearance to technological developments, the ability of bronzesmiths to make larger and more elaborate castings, including the addition of lead to the bronze alloys. Between the fifteenth and thirteenth centuries the short dagger became longer, firstly a rapier and finally a true sword. The second innovation was the leaf-shape of the blade which placed all the weight at the point, allowing the warrior to fight by slashing rather than fencing. The flange-hilt to hold the wooden handle was the third innovation, improving the warrior’s grip on the sword,. These swords have a pan-European distribution—from Britain and Scandinavia in the west to Cyprus in the east—and they are the predecessors of the swords of the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age from Syria to Ireland.

The typological ancestors of these swords are only found in and around the Hungarian Plain, and this area may have been the origin of other metalworking innovations, such as the safety-pin brooch, defensive armour (greaves, corselets, and helmets) and possibly bronze vessels. But these items were also rapidly adopted in Greece, and their development is not so clear as that of the swords.

The flange-hilted swords are found in the final phases of the Mycenaean civilisation (Late Helladic IIIb—IIIc), which has led some scholars to suggest that it was destroyed by invaders from the north, but they are in fact found in normal Mycenaean graves, and had clearly been adopted before the civilisation collapsed. It is with the fall of Mycenae that our enquiry will begin, but first we should discuss the development of iron working which makes its appearance in Greece in the same contexts as the flange-hilted swords.

The origin of iron working

Iron has such obvious advantages over bronze that one must explain why iron working was not adopted earlier. In comparison to copper, especially the tin ores required to make bronze, the basic iron ores are widely spread and available in most areas. The simplest oxides such as haematite (Fe2O3) are available in various forms either as rock ores or as bog iron, and these were the most sought after. The sulphide ores such as pyrites (FeS2) were less popular as small amounts of sulphur would make the iron brittle. But the ubiquity of the ores meant that implements could be made more locally and so more cheaply. The second advantage of iron is that it can produce a harder, tougher and sharper cutting edge. If we compare the relative hardness of iron and bronze on the Brinell scale of hardness, we obtain the following figures:

Cast bronze: 88; Hammered bronze: 228; Wrought iron: 100; Forged iron: 246+

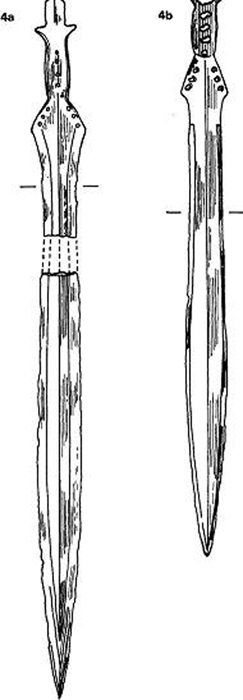

4 Late Bronze Age swords

The Erbenheim (a) and Hemigkofen (b) sword types represented a great innovation in fighting techniques. With previous technologies it had only been possible to make short blades (daggers and ‘rapiers’) which had to be rivetted to the hilts. Improved casting techniques, including the addition of lead to the bronze, allowed large and elaborate castings to be made. The hilt was cast in one with the blade, and the handle secured by side flanges and rivets, making it possible to grip the sword better, and to swing it. The thickening of the end of the blade (‘leaf-shaped’) placed all the weight at the pointed end, producing a change in fighting techniques with slashing as well as thrusting.

From their area of origin in the Hungarian Plain, these sword types spread across Europe to Britain in the West and Scandinavia in the north and they turn up sporadically in Mycenaean Greece, for instance in burials of Mycenaean IIIb-c at Enkomi on Cyprus, datable to about 1250–1200 BC. They represent one of the last contacts between Greece and the rest of Europe for three or four centuries.

These flange-hilted swords were the predecessors of a long series of local types which continued until the seventh century BC. In Greece their successors were of iron (e.g. fig 9), and these are found widely in the eastern Mediterranean. In Europe bronze continued in use until the final years of the leaf-shaped sword, with the Gündlingen and Mindelheim types of Hallstatt C (fig 18), though the latter are also known in iron.

Actual sizes: a—length 74cm; b—length 59.5cm

The problem with iron lay in the technology needed to produce an implement. The techniques of manufacture were different from those required for the other metals familiar to prehistoric mangold, copper, tin, silver and lead. All these had a relatively low melting temperature which meant that impurities could be removed at the smelting stage, and the molten metal cast in moulds. The basic techniques required for these metals were smelting, alloying with one another, casting, and hammering. Iron ore is not difficult to smelt. After pounding and roasting, it needs to be mixed with charcoal and heated to a temperature of about 1100C in a reducing atmosphere. The charcoal combines with oxygen in the air to form carbon monoxide (2CO2 to 2CO), and this in turn reduces the iron oxide, giving off carbon dioxide, and leaving behind the smelted iron.

The resulting iron ‘bloom’ left in the bottom of the furnace is a spongy mass of iron full of impurities. It first required extensive forging to remove the slag. As temperatures sufficiently high to melt the iron were unattainable, casting was impossible; the iron could only be formed into a useful implement by forging, and the hammering would both shape the object and force out some of the impurities. Even so this did not produce a hard enough cutting edge. The iron needs alloying with a small amount of carbon to produce steel, and this could only be done by heating the blade in a charcoal furnace, hammering when hot, and then quenching in water. This process needs to be repeated several times before sufficient carbon is absorbed.

With primitive technology, however, only the outer skin of iron would absorb any carbon; the core would remain pure iron with slag inclusions, and so relatively soft. The earliest answer to this problem was ‘piling’ the forging of slabs of iron together, each with a ‘skin’ of steel, so forming a composite blade of alternating iron and mild steel. Towards the end of the Iron Age, in the Alpine region, more sophisticated techniques were evolved. To form sword blades, long fine rods were welded together to give a laminated blade, while in Austria a technique of producing a mild steel containing 1.5 per cent carbon was achieved.

The adoption of iron working thus involved the smith acquiring a new range of technical skills, and the blacksmith quickly became a specialist divorced from other metalworkers. Initially it was difficult to produce iron blades which were technically superior to contemporary bronzes, so at first it was mostly adopted more for reasons of prestige rather than usability.

As with many of the major advances in prehistory, we have no idea exactly how the techniques of iron working were discovered. There is nothing in each step which involved the development of a higher technology than was already known in the third millennium BC. What was needed was to put each step into a new combination which would produce a usable implement. The advances that were being made at the same time in other aspects of metallurgy and pottery manufacture suggest that experimentation was going on to discover new ores, metals and techniques, but the earliest phase of experiment cannot be documented in the archaeological record.

We can, however, say approximately when and where the discovery was made, from the occurrence of early iron objects. The best authenticated find comes from a burial at the early Bronze Age town of Alaça Hüyük near Ankara in central Turkey, dating to around 2500–2300 BC. It is a dagger with a short iron blade; the hilt was organic, probably wood, which had been overlaid with gold sheet. The burial was found flexed in a small partition in an area defined by stone blocks which had apparently been covered over by wooden planks. Also in the burial was a bronze stag inlaid with silver, and a number of pottery and metal vessels. The burial was one of thirteen discovered in this phase of the settlement, and gravegoods from these other graves included elaborate bronze ‘standards’ formed of a grid of bronze bars with wheel pendants attached, and a gold diadem. Two points emerge. Firstly, the find is in a context of high social status—the burials are comparable with those from contemporary Mesopotamian towns such as Ur; secondly, the technology of the bronze work is as high as anywhere else in the world at this time: elaborate bivalve casting and inlay with different metals—a technology sufficiently high to permit iron working.

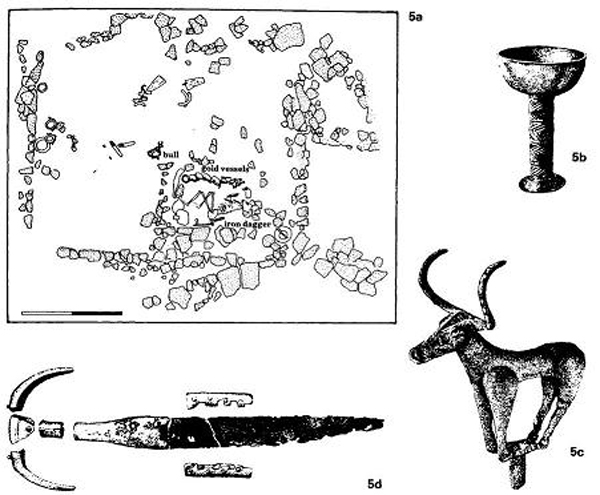

5 Alaça Hüyük, Turkey

Alaça Hüyük is a small tell in central Turkey not far north of the Hittite capital Hatussas (Bogazköy).

Excavations in the 1930s revealed a Hittite town, and, underlying it, an early Bronze Age settlement, with a series of thirteen rich burials. The graves were stonelined, with a separate compartment for the body, and apparently covered with timber planking. Some had a second level of gravegoods consisting mainly of the heads of cattle. All the burials were of high social status, and included ceremonial objects, such as cast copper figures of bulls or stags, some inlaid with precious metals, or elaborate ‘standards’ made of a grid of copper bars with hanging ring pendants.

Burial K was amongst the richest (a). The body was furnished with a diadem made of gold sheet, six gold vessels (b), two silver vessels, several gold and silver pins and beads, a silver dagger, a copper rapier, and a copper bull with eyes, tail and forehead inlaid with silver (c). The iron dagger (d) lay by the hip of the crouched skeleton. The hilt was of wood overlaid with gold and the scabbard fittings were also of gold. The burial dates to about 2500–2300 BC.

Actual sizes: b—height 12.5cm; c—height 23cm, length 29.5cm; d—total length of blade and handle 30cm

Comparable early finds are not well documented, partly due to lack of interest in finds of iron by early excavators, partly due to poor preservation. Fragments of iron have been found in hoards of third millennium date at Troy, again associated with high-prestige objects such as bronze and polished stone axes of serpentine and lapis lazuli. These discoveries from Troy and Alaça Hüyük demonstrate that iron was known and worked in small quantities over much of modern Asia Minor at the end of the third millennium BC, and that knowledge was sufficiently advanced to produce usable tools and weapons.

For the following millennium we rely mainly on documentary evidence. The sources are the clay tablets incised with cuneiform writing from the Hittite capital of Bogazköy, the ancient Hattusas, and from the Hittite town of Kanesh (Kultepe) where a residential suburb was occupied in the seventeenth century BC by an enclave of Assyrian merchants. In the latter case we are told of the materials traded, and it is possible to work out the approximate relative value by weight of the different metals being traded. The most valuable, worth five times more than gold, was iron. The merchants were dealing mainly with prestigious substances—copper, tin, gold and lapis lazuli— often as agents of the Hittite and Assyrian kings and aristocracy.

From Hattasus we possess a letter written by King Hattusilis III (1275–1255) to another, unnamed, king:

As for the good iron which you wrote about to me, good iron is not available in my seal-house at Kizzuwatna. That it is a bad time for producing iron I have written. They will produce good iron, but as yet they will not have finished. When they have finished I shall send it to you. Today now I am dispatching an iron dagger-blade to you.

A number of points emerge from this letter. Firstly, iron was a subject worthy of discussion between the most powerful rulers in the Near East and even such small items as dagger blades made worthy royal gifts. Secondly, the reference to the ‘sealhouse’ in Kizzuwatna (apparently an area in south east Turkey) implies that there was direct royal control of iron production. Further evidence of the royal status of iron comes from the tomb of Tutankhamun, where one of the two gold-hilted daggers possessed a gold blade, the other being of iron. The Hittite and Egyptian royal houses were linked by marriage, and the iron blade is presumably of Hittite origin.

Around 1200 BC the Hittite empire collapsed, at about the time when iron working appeared in Cyprus and Greece. This could be interpreted as iron working spreading only with the collapse of the Hittite monopoly over its production. However, the pattern of archaeological discoveries casts doubt on this simple interpretation. Iron objects are virtually unknown in Hittite contexts, whereas they are known in second millennium contexts too far distant for them to have been traded from Turkey—Simris in Sweden (a fragment), Bargeroosterveld in Holland (an awl), Gánovce in Czechoslovakia (an iron-hiked bronze dagger) dating between the eleventh and fifteenth centuries BC. The problem with these finds is that it is not clear what expertise in iron working they represent— only smelting or hammering, or had carburisation been discovered, as is implied by the Hittite documents? Only with the rise of the Greek iron industry can we be sure that serviceable tools and weapons of iron could be produced in quantity.

The end of Mycenaean Greece

It is at the end of the second and first millennia BC that we can detect fundamental changes which were to lead gradually to the climax of Mediterranean civilisation. These developments have their roots in, and indeed must be compared with, what had preceded them. When, for instance, we look at trade networks, we must suspect that the Greek trade was developing along the routes followed by its Mycenaean predecessor, which may not have been entirely forgotten, even though it may only have been retained in the form of myth and half-garbled stories. The east Mediterranean had been dominated in the second millennium by three fairly stable civilisations—Egypt, the Hittites based in central Turkey, and Mycenaean Greece. Whatever the cause and nature of the period of unrest which finally brought the Hittite and Mycenaean empires to an end, the universal picture of the east Mediterranean, from 1200 BC onwards, is one of decline and depopulation. In mainland Greece the centres of power, based on the defended citadel palaces of Pylos, Mycenae, Tiryns and other such centres, were deserted somewhere in the period around 1200–1100 BC. A number of causes have been postulated for this collapse: an invasion from the north, which has been tied in with the mythical Danaïds (though archaeologically this has generally been discredited); the involvement of the Greeks themselves in the so-called ‘Peoples of the Sea’, which included the Pelesta, the historical Philistines, who used pottery of Mycenaean origin; models of climatic deterioration, with a series of major droughts similar to some which are historically documented for Greece; or an attempted overexploitation of the agricultural resources which led to a final and sudden catastrophic collapse of the centralised kingdoms. Certainly we see the disappearance of many aspects of civilisation: the production of fine pottery and metalwork; the importation of luxury goods such as ivory, gold and faience; developed stone ashlar building techniques; and the Linear B tablets which had been used to keep the palaces’ accounts. There is evidence of a major drop in population, though this comes mainly from evidence of field surveys, which are themselves largely based on the availability of pottery sherds. It has been suggested, for instance, in the field survey of Messenia in south western Peloponnese that the population may have dropped by as much as to one tenth of its former size. Although this general pattern is undoubtedly true, it is difficult to translate potsherds into population sizes, and we may be seeing the collapse of the pottery industry, and indeed a period when pottery was not in great use, as much as a decline in the actual population using it. If we are to take these figures in absolute terms, then it is difficult to explain the origin of, for instance, the kingdom of Sparta, for which we have virtually no archaeological evidence until the eighth century—by which time it was already a dynamic and expanding society.

It is only in certain areas of Greece that we have a full sequence of pottery styles, and to a lesser extent of burial evidence. The main area is Attica, and especially Athens, which gives some hints of the complexity surrounding the demise of the Mycenaean civilisation. A major setback seems to have been suffered in the Mycenaean world between Mycenaean IIIb and Mycenaean IIIc, datable to somewhere around 1200 BC. In Attica Mycenaean IIIc pottery is found in certain areas, notably at Perati in eastern Attica, whereas it does not occur at Athens. Instead we find coarse handmade pottery of a much lower quality, in both production and decoration, which is generally termed sub-Mycenaean. This term implies that this coarse pottery was both a successor and a degenerate form of a preceding Mycenaean pottery, but the differing distribution within Attica of Mycenaean IIIc and sub-Mycenaean pottery had led some specialists to suggest that the two pottery forms were contemporary. In other words not all aspects of Mycenaean civilisation disappeared at the same time in all areas, and in certain areas the production of fine pottery, for instance, and indeed the building of palatial buildings may have continued on into Mycenaean IIIc. This is especially true of Cyprus, where the town of Enkomi, established during Mycenaean IIIb, continued as a flourishing settlement until as late as about 1050 BC, when it seems to have been finally destroyed by an earthquake. In this late period it still had stone buildings and stone-paved streets, and was still importing exotic goods from the Egyptian and Near Eastern world. It also seems to have maintained contacts with central Europe, as Enkomi is one of the sites to produce the flange-hilted swords of Hungarian form discussed above.

To some extent similar problems surround the situation in southern Italy and Sicily, though from here the archaeology is dependent on typology for dating, as much of the meagre evidence comes from collective tombs and cannot be placed within tight chronological sequences. But the inheritance of Mycenaean influence is fairly clear in both metal types, and in certain areas in the pottery as well. Southern Italy and Sicily had been exploited by the Mycenaean world, with the establishment of defended sites, which were perhaps trading outlets or colonies at such key points as river mouths (for instance, the site of Scoglio del Tonno, at Taranto)—sites which in some ways resembled the later Greek colonies. In south eastern Italy the pottery styles of the post-Mycenaean period represent a continuation of Mycenaean traditions, with fine painted wares which run parallel with the Geometric sequence of Greek proper. The Mycenaean influence penetrated at least as far as central Italy, as fragments of imported pots are not unkown in, for instance, Tuscany, but the links of northern Italy and especially the Po valley had traditionally been with central Europe and with the demise of the Mycenaean civilisation, it is the central European connection that becomes dominant.

Iron working in Greece

It is in this sub-Mycenaean context that iron working first became common in the eastern Mediterranean. The earliest objects turn up in a Late Helladic IIIc context, in the decades either side of 1200 BC, in cemeteries such as Perati. However, as these objects are usually found in collective tombs, in which it is difficult to assign gravegoods to individual interments, precise dating is generally impossible. The earliest objects are mostly simple, and include iron rings, and short iron knives, some of which have handles fixed with bronze rivets while others have iron rivets—which suggests a greater mastery of iron working techniques. It has been suggested that the origin of these knives is Cyprus where they also occur at sites such as Enkomi. If we follow a diffusion model for the spread of iron working from Asia Minor, Cyprus might be the logical meeting point between the Hittite and Mycenaean spheres of influence. But the majority of tools and weapons at this period are still made of bronze, such as the flange-hilted leafshaped swords from Enkomi.

Though Late Helladic IIIc may in some areas run on contemporary with sub-Mycenaean, and therefore these iron objects may be contemporary with sub-Mycenaean elsewhere, iron objects are notably more common in sub-Mycenaean contexts. In Athens, for instance, a number of iron brooches and iron rings are known from inhumation graves belonging to this period. In Athens and adjacent areas in the north western Peloponnese, there is a marked shift in burial practice; single inhumation, which, though known previously had not been common, replaced the more normal collective tholos tomb burial typical of the later Mycenaean period. In other areas such as Crete and Thessaly, however, the tholos burial rite continued well into the early Iron Age. In the sub-Mycenaean period, rich gravegoods are notable by their absence; gold and silver, if they occur, are limited to one or two finger-rings. The pottery at Athens is noticeably crude, decorated in simple motifs of geometric character, and the ornate freehand decoration of the Mycenaean period has almost totally disappeared.

Proto-Geometric Greece

This period is succeeded by the Proto-Geometric, datable to around 1150–1050 BC—though the chronology for this period and the succeeding Early Geometric is vague due to a lack of contact with areas with a firm historical chronology. The graves of this period at Athens show yet greater poverty, while precious metals, even bronze, are notable by their general absence. Settlement evidence is virtually unknown. Some trade contacts had been maintained, notably with Cyprus during the sub-Mycenaean, and the end of this period brought in major innovations, at least in the manufacture of pottery. Firstly, the potter’s wheel was introduced, and with it improvement in the quality and the treatment of the clay. Secondly, there is an innovation in the decorative techniques; though the motifs are still geometric and derived from those of the previous sub-Mycenaean period, there is much greater care taken. In the circles we see the introduction of the compass, and also of the multiple brush, which was a device by which several brushes were attached together, so that exactly parallel lines and truly concentric circles could be drawn in one operation. High-quality prestige pottery was thus established— a tradition which was to survive through into the Classical period.

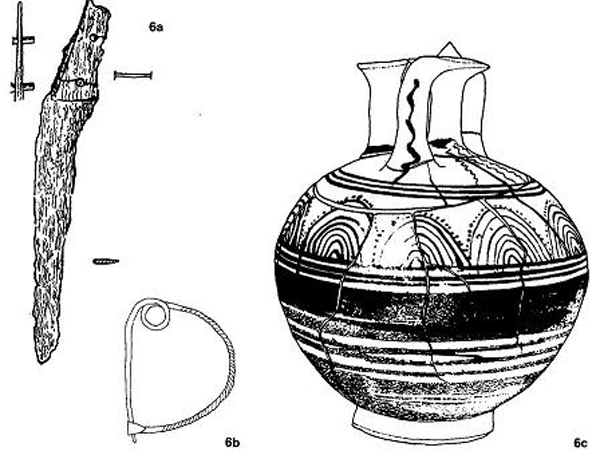

6 Sub-Mycenaean Greece

The earliest iron objects in Greece include small iron knives (a), with bronze or iron rivets, but these are mainly found in Crete and Cyprus, and are probably of Cypriot origin. They, and small iron rings, are unfortunately poorly dated as they tend to be found in collective tombs, but they appear to belong to late Helladic IIIc (late 12th-early 11th centuries BC). Simple iron objects also appear in the partly contemporary, partly subsequent Sub-Mycenaean period, for instance in Athens, in single graves with a limited range of personal jewellery such as the arc brooch (b). Increasingly in the Sub-Mycenaean, and especially during the Proto-Geometric, brooches and pins are made of iron, even for objects which in later times would normally be made of bronze. This suggests that bronze may have become more difficult to obtain, and objects of any metal other than iron are rare in the Proto-Geometric.

Mycenaean IIIc pottery had been of high quality, but Sub-Mycenaean pottery (c) is, in comparison, poorly made, with ill-prepared and ill-fired clay. The repertoire of decorative motifs becomes very restricted, with only the simplest geometric motifs, generally poorly executed. These do however form the basis for the Proto-Geometric style, which saw a revival in the quality of preparation and firing, and more carefully designed painted decoration using the compass and the multiple brush. The potter’s wheel also reappears, an investment in time and equipment that implies a clientele capable of supporting specialist crafts, and gives a picture which contrasts somewhat with the poverty of the burials of this period.

Actual sizes: a—length 15.4cm; c—height 20.6cm Scale: b—1:2

The evidence for trade contacts in the Proto-Geometric period is, however, considerably less than in any previous or succeeding period of the Bronze Age or Iron Age. Indeed, it seems as though Greece was almost completely isolated both from its more powerful eastern neighbours, and also from central Europe and Italy. Bronze is extremely rare; the sources of both copper and tin were apparently cut off by this loss of trading contact. On the other hand, iron became the standard material for producing both weapons and tools. It has been suggested that the lack of bronze is due to the adoption wholescale of an iron technology, but, as we shall see elsewhere, the introduction does not usually mean the demise of the bronze industry—rather the opposite. It is more likely that the concentration on iron was due to the difficulty in obtaining bronze. There may also have been technological innovations in iron working which led to its adoption. No longer are the objects confined to minor trinkets and knives, but for the first time full-scale weapons, like the flange-hilted iron sword from a warrior burial at Tiryns, appear, datable to about 1050 BC. The technique of ‘piling’ had perhaps already been mastered, whereby slabs of steel were welded together to produce a blade which had steel in its core rather than plain soft iron. The distribution of iron objects is, however, still largely confined to the islands such as Crete and, on the Greek mainland, to the north western part of the Peloponnese and to Attica. Though iron objects do occur sporadically elsewhere, usually in not closely datable contexts, one other area at least had adopted a fairly extensive iron-using economy—the area of the north western Aegean, in Macedonia, where the cemetery at Vergina has produced a number of iron swords, in a context which is perhaps as early as those in Greece. In this case, however, there was no lack of bronze, as this area seems to have maintained links with central Europe, and much of the other bronze material from the burials is closely similar to Urnfield types further north.

The burial rite of this period continues to be mainly single inhumation, though in Athens there is a notable move towards cremation burial rite, which was to remain the standard burial rite in Attica into classical times. Despite the poverty of the gravegoods, despite the lack of information that we have for this period generally, and despite the general lack of contact with the outside world, this is the period when we can see the beginnings of a civilisation which is noticeably Greek and which leads on to the classical world. In all areas the Mycenaean social structure had broken down completely, the palaces and citadels had all but been deserted, the bureaucracies, with their writing and their centralised control, had disappeared. Although society was not classless, evidence of social differentiation is meagre. Although there is as yet no evidence for the rise of any centres, the growing number of burials at Athens in this period demonstrates an increased density of occupation. It was not, however, centralised around the acropolis. This was an essentially agricultural society based on small villages or single farms.

Late Bronze Age Europe

The demise of the Mycenaean world must have had some effect on southern Italy and Sicily with the breakdown of trade, but we know too little of the native Bronze Age settlements to identify change. The Mycenaean styles of bronze work and pottery continued for some centuries. Otherwise there is no obvious sign that the disappearance of the east Mediterranean market for metals and amber had any influence on central and northern Europe, though ultimately it may have delayed the processes which came into play in the sixth and fifth centuries. No prestige goods from the Aegean were passing north and there was no dependence on external trade. The expanding economy and population were well able to absorb and sustain the production of raw materials. The only obvious change is in the disappearance of exceptionally rich burials. But the rich items which accompanied the dead do not disappear. Bronze body armour, shields, swords, bronze vessels, harness and wagon fittings are still relatively common, though now they occur in hoards or as stray finds in rivers. A hierarchical society still existed, but it was no longer clearly symbolised in the burial rite.

The period 1200–700 BC is one of gradual evolution of the bronze industry with no marked technological innovations, but with an ever increasing range of types, not merely weapons, tools and metal containers, but also ritual implements and musical instruments. The Irish bronze industry was particularly innovative, and its products included trumpets, rattles, and elaborate flesh forks decorated with little bronze animals, while the gold work included an exciting range of dress fastenings, gorgets, and fittings such as those on the model boat from Caergwyle, all decorated with geometric patterns of concentric circles. It is only rivalled by the Danish industry which was producing masterpieces such as the paired horns (lyrer), or the Trundholm ‘sun-chariot’. All these objects betray a rich cultural and ceremonial life behind the dull typologies of bronze objects that archaeologists produce for this period.

The bronze industries form a number of overlapping zones—in the north encompassing the north German plain and Scandinavia; in the west from Britain to southern Spain; in the south Italy; and in the centre the Urnfield groups. Each is defined in terms of decorative motifs, and types of socketed axes, palstaves, chisels and spears of localised distribution, the product of small-scale industries mass-producing every-day items. Only rarely did such items travel far from their place of manufacture. In contrast, there is a range of prestige items that often crossed from one zone to another. The various types of cups— Müllendorf, Sartrup and Jenišovice—have a distribution that extends from central Italy through Czechoslovakia and Germany into southern Scandinavia. Though there must have been a number of workshops over a wide area producing a range of almost identical products, their distribution does imply extensive contacts including trans-Alpine, in the higher echelons of society. Bronze buckets made of sheets rivetted together show a more east-west distribution, and though these are likely to be an innovation of the Hungarian Plain, they were closely imitated in western Britain, which went on to produce its own distinctive forms. These buckets were the ancestors of the bronze situlae of the Iron Age, which in northern Italy would give their name to a distinctive orientalising art form. Distributions of sword types had an intermediate apportionment. No single type was to reach anything like the area of the Hemigkofen and Erbenheim types of the twelfth-eleventh centuries until the advent of iron swords in the seventh century. Nonetheless, types such as the Ewart Park in Britain were extensively distributed within their zones.

These extensive contacts within central Europe, and extending down into Italy and Catalonia, were echoed by two other features, firstly the burial rite of cremation, and secondly by the distinctive pottery found in the graves, especially the urn itself. Typically the graves are concentrated in flat cemeteries (Urnfields), or at most under a small low tumulus, and though there may in certain cases be a range of accessory vessels, metal objects are not common, and generally the burials are marked by their lack of ostentation.

The settlement hierarchy seems rarely if ever to extend above the size of a village, and cemeteries too indicate no marked concentrations of population. Hillforts are not uncommon, but like their Iron Age successors, they do not seem to be centres of wealth, trade or industry. Though there is some evidence of differential house sizes, especially on the open settlements, it is not always clear whether this is due to different functions or social differentiation. Certain individuals did possess substantial houses, like the inhabitants of the marsh fort of the Wasserburg in Buchau in the Federsee in southern Germany and, like the burial evidence suggests, some, but not highly marked social differentiation.

The larger open settlements are often situated in the river valleys, and settlements such as Runnymede on the Thames were places where metalworking, and presumably other industrial activities were carried out. The ‘industrial villages’ were to remain a common feature of the settlement pattern of Temperate Europe as late as the first century BC. Etruria, however, was already slightly different, with clusters of villages on defensive plateaux, a phenomenon which will be discussed further in the next chapter. Only rarely did anything more specialised appear, and this was usually connected with mineral extraction. Specialist communities were already mining copper ores in elaborate underground mines in the Austrian Tyrol, and around 1000 BC, this mining skill was extended to salt extraction with the earliest phase of mining at Hallstatt. This first period of mining was to last at Hallstatt for about 200 years before the entrance was blocked off, apparently deliberately.

It is difficult with such societies to say much of the social and political organisation. Each village or hillfort seems to be an independent unit, equal in status to its neighbours, though presumably they were linked into larger groupings. Only in the Lausitz Urnfield groups of southern Poland are there hints of larger regional organisation with defended lakeside forts such as Biskupin, with a cluster of small settlements and villages around, and also clusters of hillforts, separated by areas of unsettled land. But the major phase of these Lausitz societies is the seventh century, taking us already into the Iron Age. Other than hillforts, there is no construction of communal buildings or ceremonial centres.

Temperate Europe in the late Bronze Age thus presents a picture of steady, but unspectacular growth. Local disasters there may have been, like the flooding and abandonment of the Swiss lake villages, or the eventual desertion of the Lausitz settlements of southern Poland, confirmed by the forest regeneration in the pollen record. But these had little or no impact outside their immediate areas. Warfare was rife, as both weapons and hillforts testify, but again this was localised, and there is no evidence for widescale transplantation of the population which occasionally occurred in the Iron Age.