4

Sociocultural theory

A dialectical approach to L2 research

James P. Lantolf

Historical discussion

Although sociocultural theory (SCT) is a general theory of human mental development, it has been productively extended to include the investigation of second language (L2) development. I think it is fair to say that the catalyst for SCT-informed L2 research (henceforth, SCT-L2) in the West was the publication of Frawley and Lantolf's (1985) study on the narrative performance of ESL speakers. Adopting the perspective of mediated-mind, the core concept of SCT (see below), Frawley and Lantolf showed how speakers lose, maintain, and regain control of their narrative performance through private speech.

One of the most influential SCT-L2 studies that followed Frawley and Lantolf's article was a paper by Aljaafreh and Lantolf (1994), which examined the relevance of the zone of proximal development (henceforth, ZPD) for L2 learning. The researchers argued that for feedback to be effective in promoting language development it had to be sensitive to a learner's ZPD, defined by Vygotsky (1978) as the difference between what individuals can do independently and what they can do with appropriate mediation from someone else. This is an important concept because the theory argues that development does not depend solely on internal mechanisms but on the quality and quantity of external forms of social interaction that is attuned to a learner's potential ability.

Lantolf and Thorne (2006) was the first book-length synthesis of SCT-L2 research. This work explained the core concepts of the theory, including mediation, internalization, ZPD, and activity theory, and discussed these in light of L2 research. It also laid the foundation for investigating the impact of SCT principles for language teaching programs. Lantolf and Poehner (2008) followed up on this aspect of the SCT-L2 research agenda with a collection of papers that report on the effects of SCT-L2 pedagogy on L2 development.1

SCT-L2 research encompasses an array of topics, all of which are connected to the basic concept of the general theory: human thinking is mediated by culturally organized and transmitted symbolic meaning. Vygotsky (1987, 1978) argued that the relationship between humans and the world is indirect and therefore mediated not only by physical tools, such as shovels, hammers, and saws, but also by symbolic tools, including art, numbers, and above all, language. Tools, physical and symbolic, empower humans to control and change the world in which they live. The latter, in particular, allow humans to intentionally control aspects of the neuropsycho-logical functioning of their brains. Thus, when children master language as a meaning-making system they also master their own cognitive activity. This mastery gives rise to the mind, which for Vygotsky is not co-terminus with the brain, but extends into the body (e.g., gestures) and even into artifacts such as computers, with which we form functional systems that enhance our capacity to think (see Wertsch, 1998).

Core issues

Given the central tenet of the theory (i.e., that higher forms of thinking are symbolically mediated) two questions suggest themselves with regard to L2 learning: to what extent can learners deploy a new symbolic system to mediate their communicative and psychological behavior? How does this new system develop? A related question is whether or not there are significant differences between learning a new symbolic system on one's own versus learning the system with intentional guidance and support as occurs in the educational setting.

Cognitive use of L2

The SCT-L2 research that has addressed the first question shows that while learners can develop the ability to use a new language for communicative functions, using it for psychological mediation is quite a different matter. Pavlenko and Lantolf's (2000) analysis of the immersion experiences of immigrants provides evidence of the reorganization of the individual's inner order such that the person is able to mediate their thinking through the new language. Work carried out on classroom learners, including those with extended study abroad experiences (e.g., two to three years), however, has shown that even when learners are communicatively competent in the new language, they continue to think through their L1. Grabois (1997) for example found that the conceptual organization of L2 learners of Spanish with and without study abroad experiences was no different in their L2 than in their L1, English. Only learners who had been living in Spain for a minimum of ten years showed any indication of a shift away from their native pattern of lexical organization and toward an L2 pattern. The experimental study by Centeno-Cortés and Jiménez-Jiménez (2004) on the relationship between L2 private speech and completion of cognitive tasks found that when tasks become complex learners, including those at advanced levels of proficiency (i.e., graduate students in a Spanish doctoral program with extensive study-abroad experience) were unable to complete the tasks successfully if they used the L2 to regulate their cognitive functioning. They were only successful if they relied on private speech in their L1, English.

We now turn to the speech-gesture interface. Research carried out on the interface of speech and gesture within the “thinking for speaking” (TFS) framework proposed by Slobin (1996, 2003) has uncovered evidence that some L2 learners have shifted from an L1 to an L2 TFS pattern. McNeill (2005) proposes that speech and gesture form a dialectical unity of symbolic representation and material image where thinking finds its object. He calls this unity the Growth Point and argues that it can be observed at the point where hand movement synchronizes with speech. It turns out that synchronization patterns differently in different languages. Thus, when describing motion events (e.g., The cat crawled up the drainpipe) English speakers often focus on manner of movement (i.e., crawl) and manifest this not only in speech but in the synchronization of hand movements depicting the movement with the manner-conflated verb. In a language such as Spanish, which does not have a robust inventory of manner verbs, speakers more often focus on direction rather than on manner of movement and as such coordinate the movement of their hands in an upward direction with articulation of a verb such as subir (to ascend).

Research by Negueruela et al. (2004) on advanced Spanish and English L2 speakers and by Choi and Lantolf (2008) on advanced Korean and English L2 speakers report no evidence of a shift from L1 to L2 patterns for any of the speakers included in their respective projects. However, Gullberg (in press) does uncover some evidence of a shift in her study of Dutch learners of L2 French with regard to placement verbs (e.g., put, place, lay, set). Stam (2008) also reports evidence of a shift with regard to path, though not manner, of motion among Spanish learners of L2 English.

The learning process

Vygotsky proposed two related mechanisms to account for the emergence of psychological processes from social activity. The first is imitation and the second is the zone of proximal development. Imitation is understood not as mindless copying of patterns often associated with behaviorist psychology but as a uniquely human form of cultural transmission (Tomasello, 1999, p. 81) “aimed at the future” and which creates something new “out of saying or doing ‘the same thing’” (Newman and Holzman, 1993, p. 151). Human imitation, as distinct from animal mimicry not only replicates the observed model but, unlike mimicry, it incorporates the intentions of the person producing the model (Gergely and Csibra, 2007). Thus, through imitation learners build up repertoires of resources for future performances, but these need not be precise replicas of the original model.

James Mark Baldwin, an early American social scientist distinguishes two types of imitation: imitative suggestion and persistent imitation (Sewny, 1945). Through the former an individual gradually moves closer to a given model over a series of trials resulting in a “faithful replication of the model” (Valsiner, 2000, p. 30). Through the latter an individual reconstructs “the model in new ways” enabling the person to “preadapt” to future performances (ibid.). The difference in outcome can be ascribed to the fact that in imitative suggestion the target is the original model, while in persistent imitation the target is the individual's imitation of the original model, which may or may not be fully accurate. In the case of language learning imitative suggestion would be more likely to occur when frequent exemplars of the model are available and are attended to either for internally motivated reasons (e.g., attaining target-like performance) or are pushed by someone else. This is particularly pertinent in traditional educational settings which value precision of imitation over transformation of a model (Valsiner, 2000, p. 30). Persistent imitation would be a more likely process when learners either do not have robust access to exemplars of the original model, for whatever reason fail to pay attention even if exemplars are available, or intentionally choose to ignore the original model because of perceived communicative needs.

The difference between imitative suggestion and persistent imitation has potentially interesting implications for the role of recasts in learning. As the literature documents, learners at times repeat recasts accurately, at other times they do not, and at still other times they fail to repeat the recast at all (see Loewen and Philp, 2006). Vygotsky (1987, p. 211) argues that development is a collaborative process in which individuals move from what they are incapable of to what they are able to do through imitation. This transition takes place in the ZPD—the collaborative activity where “imitation is the source of instruction's influence on development” (Vygotsky, 1987, pp. 211–212). In the ZPD teachers, or more capable peers, guide learners to carry out activities they are incapable of on their own. In so doing, however, the learners internalize the ability or knowledge, which allows them to perform independently of other-mediation. Crucially, according to Vygotsky (1987, p. 212), for instruction to be effective (i.e., to lead to development) it must be sensitive to what learners are able to imitate under other-mediation. This ability is an indication of their future development (i.e., what they will eventually know or be able to do on their own). Thus, even less than precise imitation of a recast could signal future-oriented development, while failure to imitate could indicate that the model is not yet within a learner's ZPD.

To illustrate imitation as understood by Vygotsky, consider a learner of German who produces the following utterance: *Ich rufe meine Mutter jeden Tag “I call my mother every day” and then receives the partial recast from her teacher jeden Tag an (separable prefix of the verb anrufen “to call”). The student repeats the entire utterance with the correction “Ich rufe meine Mutter jeden Tag an.” Later, the same student produces the following utterance: “*Ich empfehle das neues Buch an”“I recommend the new book,” but incorporates an incorrect separable prefix. The verb in this case is empfehlen not *anempfehlen. One might argue that the student used analogy to create the innovative, though incorrect, verb. In other words, analogy is essentially an imitative process where one uses something already known to create something new.

Within SCT-L2 recasts are situated within a broader framework of mediation that is most effective when it is sensitive to learners’ ZPD and as such they represent one type of mediation. One of the important findings of SCT-L2 research is that by focusing on the types of mediation negotiated between learners and others (teachers, peers, tutors, etc.) the process of development is understood in a different way than it is in other models of second language acquisition (SLA). This is because development begins as a social process and gradually becomes a psychological process. Thus, development it not only a matter of changes in the product of learning (i.e., moving from less to more accurate production) but it is also indicated by shifts in the quality and quantity of negotiated mediation (Aljaafreh and Lantolf, 1994). At one point a learner may require explicit mediation, as for instance when a teacher provides a recast or a recast accompanied by a metalinguistic explanation. At a later point the learner may still have problems using the feature but overcoming the problem no longer requires explicit mediation and may instead result from an implicit prompt such as pausing on the part of the teacher. The shift in mediation over time is a sign that development has taken place because control over the feature is moving from the intermental to the intra-mental plane.

Some researchers (e.g., Ellis et al., 2009) have proposed that because explicit feedback appears to be more effective than implicit feedback, it should be more efficient to always provide explicit feedback. However, development is not only about improvements in performance but also about control over the performance. Consequently, learners need to have the opportunity to take control of their behavior. Thus, mediation attuned to learner ability and responsivity is not only about feedback but it is also about helping learners attain a sense of agency in their new language (see Lantolf and Poehner, 2011). This is more difficult to achieve if corrective moves are not attuned to learner development and instead follow the same format (see Nassaji and Swain, 2000).

Although the most effective form of mediation is negotiated between learners and experts, it is also possible for peers to mediate each other's development in the ZPD. Donato (1994) was one of the first SCT-L2 researchers to provide support for peer mediation in his analysis of collective scaffolding among L2 learners of French. More recently, Swain (2006) has proposed the concept of languaging to describe the talk (it can also entail writing) learners engage in as a means of internalizing a new language. This talk is communicative in appearance but psychological in function because its focus is on language form rather than on message meaning. Essentially, “languaging serves to mediate cognition” (Swain, 2006, p. 97) about language and it enables learners to notice differences between their performance and a model and serves to resolve the differences; in other words, to create a more faithful imitation of the model. The process can involve collaborative dialog, as illustrated in much of the research of Swain and her colleagues (e.g., Swain and Lapkin, 2002; Watanabe, 2004; Swain et al., 2009), as well as private speech, as documented in Ohta (2001), Centeno-Cortés (2003), and Lantolf (2003).

Data and common elicitation measures

Vygotsky argued that it was necessary to develop a new research methodology to reflect the new theory of mind he proposed. The new methodology is referred to as the genetic method (Vygotsky, 1978; Wertsch, 1985). He reasoned that if researchers attempt to study mental processes after they have been fully formed, as is the case in normal adult cognition, it is impossible to observe anything other than something such as the pushing of a button in a laboratory experiment. He also was skeptical of methods that rely on introspection, such as think-aloud research because if language is implicated in the thinking process itself rather than simply a means of expressing fully formed thought, the very act of reflecting on a process through talking about it, in Swain's terms (2006), languaging, is likely to affect that process. As Smagorinsky (2001, p. 240) remarks, “If thinking becomes rearticulated through the process of speech, then the protocol is not simply representative of meaning. It is, rather, an agent in the production of meaning” (p. 240).

Vygotsky (1978) reasoned that because human thinking is mediated by what are originally external means (e.g., social communication involving symbolic artifacts), it would be possible to observe and study thinking as it is being formed in the early phases of human development when children are externally mediated. The method he and his colleagues proposed to carry out their research agenda is known as the genetic method, which incorporates what they called the “functional method of double stimulation” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 74. Italics in original). The term “genetic” refers to the fact that the goal of research is to trace the development of thinking over time as it is being formed through external mediation.

In research with young children, they are given problems that are beyond their current abilities to solve. A neutral object is placed nearby and researchers then observe if and how children incorporate the object as a sign to mediate their thinking as they attempt to solve the problem. A classic study using “double stimulation” was Leontiev's forbidden color task, where children were asked a series of questions that were likely to elicit color terms in response. The children were to avoid specific colors. When asked the color of their house (assuming the forbidden color was white) very young children answered truthfully that it was white. Strips of differently colored paper, including white, were then placed next to the children and they were told they could use these to help them remember the forbidden color. Young children were unable to use the paper strips to mediate their thinking; that is, to remind themselves of the forbidden color. Older children, however, were able to mediate themselves by placing the relevant colored paper in a visible location and before responding to a question, they looked at the paper and successfully avoided the color. Older children, and adults, as with the youngest group, did not use the colored paper, but, unlike the youngest participants, they had no problem avoiding the forbidden color. This is because they had internalized the capacity to mediate their thinking covertly through inner speech and therefore had no need for external mediation. In such experiments Vygotsky and his colleagues were able to trace the transition of mediation from the external to the internal plane of processing over time, as represented in the different age groups participating in such studies.

The genetic method in SCT-L2 research

The genetic method has figured into SCT-L2 research in at least two ways. First is the intra-mental function language itself fulfills in learning a new language. The fact that individuals are confronted with the demanding task of learning a new language creates cognitive dissonance that is far more complex than the forbidden color task described above. To overcome the challenge, learners press their language system into service to mediate their own learning. Lantolf (1997) proposed that private speech serves as a cognitive tool to mediate L2 learning, just as it serves as a cognitive tool to learn other kinds of information. He also argued that learning, in the absence of audible private speech, is not possible and that in fact, private speech provides a glimpse into the learning process itself.

L2 private speech. Several studies have examined the role of private speech in L2 learning. Saville-Troike (1988) studied the private speech of children learning L2 English in a content classroom over a six-month period. The researcher was able to document a relationship between the patterns that children practiced in their private speech phase of development (i.e., the period of time from one to 23 weeks, depending on the child) and the patterns they produced when they began to use English in social interaction with their classmates and teacher. Ohta (2001), Lantolf and Yáñez-Prieto (2003), Lantolf (2003), and de Guerrero (2005) investigated the developmental function of private speech in adult L2 learners. The first three studies collected actual samples of private speech produced in learning environments; the fourth included a great deal of survey data in which learners were asked how they thought they used private speech to learn and think through the L2.

Ohta's study, by far the most robust investigation of adult classroom learners, tracked the private speech of L2 Japanese learners over the course of an entire academic year. The participants produced three different types of private speech: vicarious response, where an individual privately responds to a question directed to someone else, completes another's utterance, or repairs an error committed by someone else; repetition, where an individual repeats a word, phrase, or entire utterance produced by someone else or by the learner himself/herself; manipulation, where an individual modifies morphosyntactic or phonological patterns usually produced by someone else. The last two types, which in my view, qualify as imitation, were documented by Lantolf (2003), Lantolf and Yáñez-Prieto (2003) and Saville-Troike (1988). A significant difference between the adults and the children, however, is that the adults also used their L1 as metalanguage to organize and comment on their performance, while the children did not. For example, the learner studied by Lantolf and Yáñez-Prieto (2003, p. 106) when vicariously (to use Ohta's terminology) participating in an exchange between the instructor and another student regarding verb agreement in Spanish se-passive constructions, not only completes the instructor's utterance directed at another student (“Se what?”) with the correct past-tense plural form of the verb vendieron “they sold,” but also tells herself, quietly in English, “I knew it!” Lee (2006) documents use of L1 Korean and L2 English private speech among students enrolled in a US medical school. The students used L2 to work on correct pronunciation of new bio-medical terms but relied on their L1 to internalize the meanings of terms. Centeno-Cortés (2003) in a genetic study of Spanish L2 learners during study abroad was able to document the early appearance of specific features of Spanish in learner private speech and use of the same features in later social speech.

Social mediation. The genetic method has also been used in SCT-L2 research to explore the influence of social mediation on L2 development. The study reported in Aljaafreh and Lantolf (1994) analyzes the effects of learner-expert interaction in the ZPD among three L2 learners of English. In tracing the development of four high-frequency grammatical features (i.e., article use, tense marking, preposition use, and modal verbs) over a two-month period the study presents four significant findings. First, mediation negotiated in the ZPD between learner and expert varies across an explicit-implicit continuum, such that learner control over a particular L2 feature is a function of movement along the continuum, with less control being indicated by more explicit mediation and enhanced control by more implicit mediation on the part of the expert. Second, different linguistic features for the same learner may require different levels (explicit-implicit) of mediation, and mediation relative to the same linguistic feature may vary across learners. Third, microgenetic development passes through five different levels beginning at the lowest level where even with explicit mediation the learner has little if any awareness and virtually no control over use of a particular feature and culminating at the level where the learner uses the feature systematically and correctly with self-repair when necessary. Lantolf and Poehner (2006) refined the five-level developmental trajectory, when they discovered that even when learner performance is relatively error-free and when learners were able to self-correct mistakes, they continue to look to the mediator for confirmation that their performance was indeed appropriate. Fourth, effectiveness of mediation along the mediational continuum (or regulatory scale, to use Aljaafreh and Lantolf's terminology) is not a matter of whether it is implicit or explicit in any absolute sense, but what a particular learner needs as negotiated with a mediator.

Swain and her colleagues have investigated the effect of peer mediation on L2 learning. An important aspect of the languaging framework that informs Swain's research is the argument that even though speaking appears to be communicative it can, simultaneously have a psychological function. This notion is rooted in Vygotsky's (1987) claim that speech is a reflexive tool that can be directed outwardly at other individuals and inwardly at the speaker. Wells (1999) argues that this dual potential of speech (and writing) can occur simultaneously so that when talking to others, one can at the same time be talking to the self. Swain and Lapkin (2002) and Tocalli-Beller and Swain (2005) demonstrate the positive effects on learning of peer languaging activity. In both studies the researchers documented learning, at least in the short term, through use of post-tests developed on the basis of those language features that were in focus during language related episodes (LREs) (i.e., segments of dialog where learners negotiate form rather than meaning). They provide evidence that learners are able to mediate each other's as well as their own learning through talk. An especially important finding of this research is that even though learners ostensibly focus on the same language feature during LREs they do not necessarily appropriate precisely the same thing from the interaction. This can be explained by the fact that learners do not necessarily have the same ZPD. Finally, Swain and her colleagues observed that during LREs, the learners not only produced speech that was intended for their interlocutor, but they also generated talk that clearly displayed the profile of private speech (i.e., low volume, lack of eye contact, and no apparent expectation of a response; see Saville-Troike, 1988).

Applications

From the early days of the field SLA researchers have worried about the application of theory and research to pedagogical practice. Indeed, Crookes (1998, p. 6) notes that “If the relationship were simple, or not a source of concern, I do not think it would come up so often.” The solution that most SLA researchers have proposed for addressing the research-practice gap has been focused on ways of making research findings and theoretical models comprehensible and usable for classroom teachers (see Erlam, 2008). Another way of dealing with the troubling situation is to propose an approach which unifies theory/research and practice into a single reciprocal system. In the following section, I consider such a solution in some detail.

L2 praxis

Vygotsky was a profoundly dialectical thinker, who understood the advantages of unifying rather than dichotomizing oppositional perspectives in the study of human psychological processes (Levitin, 1982). This not only enabled him to create a new psychology that overcame the crisis stemming from the long-standing Cartesian mind-body dualism that had afflicted psychology virtually from its inception, but it also allowed him to propose insightful solutions to specific problems within psychology. One of these had to do with the relationship between theory/research and practice, a dichotomy that was particularly problematic for education and which finds its contemporary instantiation in the theory/research-practice gap in applied linguistics.

According to Vygotsky, in dualistic approaches to science theory was “not dependent on practice” instead “practice was the conclusion, the application, an excursion beyond the boundaries of science, an operation which lay outside science and came after, which began after the scientific operation was considered completed” (Vygotsky, 1926/2004, p. 304). In dialectical epistemology, on the other hand, practice is integrated with theory in that it “sets the tasks and serves as the supreme judge of theory, as its truth criterion” (ibid.). On this view, theory without practice is verbalizm, while practice without theory is mindless activity (Vygotsky, 1987). The unity of theory and practice is known as praxis (see Sanchez Vazquez, 1977) as derived from Marx's well-known Eleventh Thesis on Feuerbach: “The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways; the point, however, is to change it” (Marx, 1978, p. 145) [italics in original].

In praxis the unity of theory and practice means that each component necessarily informs and guides the other. The worry of whether or not theory/research applies to teaching is mitigated by the very nature of praxis itself. The research that tests the theory is practice and the process that guides practice is the theory. Hence, there is no gap between theory and practice to bridge because both the processes necessarily work in consort always and everywhere.

Beginning with Negueruela's (2003) dissertation, praxis has been taken seriously by SCT-L2 researchers. This research is carried out in real classrooms and is designed to implement and thereby test the principles of the theory in educational activity, while at the same time improving learning through theory-guided practice. Several other dissertations followed Negueruela's (see below), and Lantolf and Poehner (2008) published an edited volume, which is a collection of chapters reporting on praxis-based L2 research.

Concept-based instruction

Education, according to SCT, is, if properly organized, the activity that promotes a specific type of development—development that does not readily occur in the everyday world. Vygotsky (1926/ 2004) refers to education as the “artificial” development of individuals. It is artificial because it entails intentional explicit mediation, whereby specific signs are introduced into “an ongoing flow of activity by an ‘external agent’ (i.e., a teacher)” (Wertsch, 2007, p. 185). This is markedly different from the implicit, or spontaneous (Vygotsky's, 1987 term) development that generally occurs in the everyday world where “signs in the form of natural language that have evolved in the service of communication and are then harnessed in other forms of activity” (Wertsch, 2007, p. 185). This means that language development in and out of educational activity is a different process—a position that contrasts with SLA researchers who argue that development is psychologically the same process regardless of where or when it occurs (e.g., Long, 2007; Robinson and Ellis, 2008). The basic difference between everyday development, where learners are more or less left to their own devices, and developmental education (e.g., Davydov, 2004) is that the latter must be guided by well-organized and explicit scientific concepts, whereas in the former learners rarely have access to such knowledge and therefore must figure out on their own the patterns of the new language. Above all, rather than waiting for individuals to become developmentally ready to learn, in developmental education instruction itself “results in mental development and sets in motion a variety of developmental processes that would be impossible apart from learning” (Vygotsky, 1978, p. 90). The central unit of concept-based instruction (CBI), that is, instruction that leads development, is well-organized systematic knowledge, which is referred to as scientific knowledge.

Scientific knowledge, as contrasted with commonsense everyday knowledge, reflects the “generalizations of the experience of humankind that is fixed in science, understood in the broadest sense of the term to include both natural and social sciences as well as the humanities” (Karpov, 2003, p. 71). It manifests the “essential characteristics of objects or events” and presents these “in the form of symbolic and graphic models” (Karpov, 2003). Although L2 research has increasingly shown that explicit knowledge has a positive impact on learning (e.g., Ellis, 2006; Norris and Ortega, 2000), to my knowledge, only DeKeyser (1998) has argued that it is important to pay attention to the quality of this knowledge. Rules-of-thumb, for example, described by Hammerly (1982, p. 142) as “simple, nontechnical, close to popular/traditional notions” [italics in original], a staple of explicit instruction, do not qualify as scientific knowledge because they are superficial, non-generalizable, and more or less reflect commonsense understanding of language. Whitley (1986, p. 108) provides an example of a rule-of-thumb on verbal aspect typically found in Spanish L2 textbooks: preterit “reports, records, narrates, and in the case of certain verbs (e.g., saber, querer, poder) causes a change of meaning” and imperfect “tells what was happening, recalls what used to happen, describes a physical or mental emotion, tells time in the past, describes the background and sets the stage upon which another action occurred” (p. 108). According to Hammerly (1982, p. 142), rules-of-thumb are preferred over in-depth knowledge because the latter is usually complex and “too much for students to absorb” (Hammerly, 1982). The problem, however, is that rules-of-thumb are often vague and at best describe what is typical of a specific context and therefore have limited generalizability.

The challenge is to formulate appropriate scientific knowledge in a way that learners can understand it and use it to guide their own performance. Piotr Gal'perin, a leading pedagogical scholar of the SCT school (see Haenen, 1996) proposed that for systematic conceptual knowledge to be effectively appropriated and internalized by learners it had to be converted from verbal to visual form. Graphic depictions present knowledge holistically rather than sequentially and they mitigate against rote memorization without understanding (see Ausubel, 1970). In a series of studies, Talyzina (1981) demonstrated the superiority of graphically organized over verbally represented concepts on learner understanding in a wide array of school subjects.

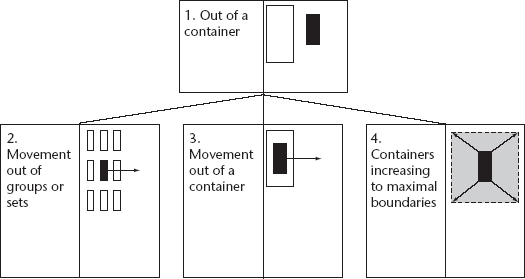

The fact that SCT-L2 pedagogy relies on explicit conceptual knowledge as its unit of pedagogical action does not mean that communicative tasks or other activities designed to stimulate interaction among students is taken off the table. Quite the contrary, these remain as the centerpiece of practice, but the practice is guided by the concepts, which Gal'perin labels as schema of the orienting basis of action or SCOBA. An example of a SCOBA developed by Lee (in progress) is given in Figure 4.1 below. This SCOBA is intended for instruction on English phrasal verbs, a notoriously difficult feature of the language especially with regard to figurative meanings. The following sentences illustrate one literal and one figurative meaning depicted in each of the four subcomponents of Figure 4.1: (1) John was out of the house for the entire day; Patrick was out of his mind with fear when he read the threatening letter; (2) Mary picked out the dresses that she liked best; Rebecca laid out the optimal solution in clear terms; (3) The soldiers parachuted out of the airplane when it reached the target; Jack went out on a limb to convince the teacher of his perspective; (4) The explosion blew out the sides of the building; The union and the company worked out a contract that was good for both parties.

On the pre- and post-tests used in Lee's study, her students (N = 23) improved on their accurate interpretation of “out” constructions from 56 percent to 71 percent.

Swain et al. (2009) also report positive results in a developmental study of voice in L2 French where learners not only improved their performance but, as argued for by Negueruela (2008), they also improved their understanding of the concept of voice. On the other hand, a study discussed in Ferreira and Lantolf (2008) yielded mixed findings. The study was based on a semester-long university course on ESL writing in which genre as defined in Systemic-Functional Linguistics was the scientific concept around which the course was organized. Although some of the students improved in their writing, as assessed by independent judges, and in their understanding of the concept of genre, as determined by explanations of their own performance, other students were resistant to the praxis-based approach, because it seemed too “theoretical” and at odds with their previous heavily empirically based approach to instruction (i.e., “just tell me what to write and I'll write it”).

Figure 4.1 SCOBA for particle “out”

Source: (Lee, in progress)

Dynamic assessment

As with other aspects of the general theory, dynamic assessment (DA), which is the pedagogical instantiation of the ZPD, emerges naturally from the dialectical perspective. It merges teaching and assessment into a single pedagogical unity. In traditional assessments, the intrusion of someone else into the process is proscribed because it introduces an error factor, while in DA the intrusion, understood as mediation, is required. DA is based on the principle that human thinking develops in accordance with the quality of mediation afforded by social interaction. Thus, to miss opportunities to mediate the individual (or a group) is to miss opportunities to promote development. Effective assessment calls for mediation for without it development is inhibited. By the same token, effective instruction calls for assessment because the teacher needs to be aware of and bring to the surface those capacities that are ripening (Vygotsky's, 1987 terminology) and that often remain hidden from view in traditional assessment and instruction that is not sensitive to the ZPD. Said another way, in DA instruction leads development while at the same time development lays the foundation for further instruction.

Antón (2009) discusses the use of DA for advanced placement in a university Spanish L2 program. She showed that while students might exhibit similar independent (i.e., non-mediated) performance when narrating a video story, under mediation significant differences could emerge. Some students with mediation were able to repair many of their independently produced errors (e.g., marking tense and aspect), while others, even with mediation were unable to do so. The students projected differential future development and consequently were placed in different courses where instruction would be more appropriately tailored to their needs. Had the placements been made on the basis of independent performance alone, many of the learners would have been misplaced.

Ableeva (2010) conducted an in-depth study of listening comprehension, a relatively under-researched area of SLA. She carried out a four-month study of seven intermediate university learners of French. Using a series of video recall protocols to diagnose their abilities, Ableeva showed that learner performance determined by recall of the number of recalled propositions contained in the native speaker videos improved with statistical significance as a result of the DA sessions she conducted with the learners. This included not only the original video texts, but also more difficult texts, designed to assess learner ability to extend learning to new circumstances. Poehner (2007) stresses the importance of transcendence, or the capacity to transfer what is learned to different activities, as a true indication of development. In addition, and as in Antón's study of oral proficiency, mediation during listening comprehension was able to bring to the surface problem areas (i.e., phonology, lexicon, grammar, and cultural knowledge) that might otherwise have remained hidden from scrutiny.

A critique often leveled against DA, and against work on the ZPD in general, is that it requires a great deal of time and effort on the part of the mediator/teacher to support the development of individual learners. A response to the critique both within the general SCT (Newman, and et al., 1989) and the SCT-L2 literature has been to show how DA and ZPD principles can be implemented at the group or even classroom level (see Gibbons, 2003; Guk and Kellogg, 2007; Lantolf and Poehner, 2009–2011).

Gibbons uses the ZPD as a lens for analyzing the interaction between elementary teachers of content-based ESL and their students. She documents how the teachers attempt in a whole-class format (following small group work by the students) to mediate the students into using appropriate scientific jargon instead of everyday terms. Guk and Kellogg (2007) analyze a fifth-year elementary school EFL class in Korea. The activity comprised two components: in the first the teacher explained and demonstrated a task to a group of students each of whom was then to explain the task to their respective groups. In teacher-student interaction the teacher provided analytical explanations of the language in the L2 with students responding appropriately in this language; whereas in the student- student interactions, most of the talk was conducted in the L1 with lengthier explanations. The authors propose that the teacher-student interactions served inter-mental functions and as such represented the upper limit of the ZPD, while the student-student interactions served intra-mental (i.e., internalization) functions and therefore represented the lower limit of the ZPD. However, neither study documents specific learning outcomes.

The study by Lantolf and Poehner (2009–2011) documents how an elementary school Spanish teacher effectively implements DA into her regular instructional program to promote learner development. Having worked through Lantolf and Poehner's (2006) Teacher's Guide, the teacher established a prefabricated menu of hints and prompts arranged from most implicit (i.e., pause in responding to student performance) to most explicit (i.e., providing the correct response with an appropriate explanation). She then designed a simple grid sheet that included the name of each student, the planned activities for each instructional session, along with the prompts and hints. She assigned a numerical score to each of these from 1 (pause) to 8 (correct response with explanation) with a 0 assigned if a student did not require any mediation. For each class activity students were assigned a score depending on the type of mediation needed. This allowed the teacher to compare students in a given activity as well as track the performance of individual students over time. Lantolf and Poehner (2009–2011) traced the improvement in performance of one student's use of noun-adjective agreement (number and gender). In addition, Poehner (2009) argues for the distributed effect of whole-class DA in that students not directly interacting with the teacher appear to have benefited by attending to the mediation provided to classmates.

Future directions

Future research within the SCT-L2 paradigm should address four general areas. The first is the relationship between private speech and internalization. To my knowledge since the publication of the research reviewed in this chapter no work has been conducted on this important topic. The research methodology should be based on that used by Ohta and Saville-Troike and should extend over a reasonably long time span (e.g., six months to a year, at least). This will be labor-intensive research but there is much to be gained from its outcome both for those interested in SCT research and also for those interested in the relationship between recasts and other forms of feedback and L2 learning. The particular importance of private speech is that it allows researchers a glimpse of language learning in “flight” (Vygotsky, 1987).

The second area is DA. Although of the four, this has received the lion's share of attention, there is still much work to be done. One of the most challenging, yet most important, topics is research on how to effectively implement DA in large group formats. The approach taken by the teacher in Lantolf and Poehner's study is only one way of tackling the problem. One can imagine technology-based approaches to mediation illustrated in a funded research project currently under way on computerized DA in French, Russian and Chinese (see Lantolf and Poehner, 2009–2011). An especially promising approach, which has been developed by Cole and Engeström (1993) in which reading instruction is based on the concept of division of labor, whereby the reading process is deconstructed with various of its subcomponents assigned to individual students as the whole class undertakes to collectively read a given text. Together the class, guided by the teacher, socially constructs expertise in reading and by participating in this process individual students develop through their particular ZPD.

Concept-based instruction is an extremely promising area for future SCT-L2 research. So far most of the work here has been concerned with grammar instruction. In this regard, there seems to be a natural fit between CBI and cognitive linguistics. In my view (see Lantolf, in press), cognitive linguistics is especially congruent with SCT-L2 pedagogy because of the kinds of theoretical/ conceptual information it develops about language and because of its use of graphic depiction of theoretical statements about language that are potential candidates for SCOBAs (see Figure 4.1 above). To date, only one CBI study (Thorne et al., 2008) has addressed instruction in the domain of pragmatics and only one (Yáñez-Prieto, 2008) has dealt with learning of figurative language (see Littlemore and Low, 2006). Both areas are especially important for the development of advanced levels of L2 proficiency. I believe that SCT-L2, because of its concern with meaning, can make a significant contribution to helping learners develop proficiency in the area of conceptual fluency (see Danesi, 2008).

Finally, research on gesture has demonstrated that this mode of communication and thinking can have a powerful impact on learning (see Goldin-Meadow et al., 2009). Gesture, because it is imagistic, shares a great deal with SCOBAs. Some L2 researchers (Haught and McCafferty, 2008; Lantolf, 2010) have already shown that gesture has considerable potential for mediating L2 learning and performance. It is worth the effort for research to focus on ways of connecting SCOBAs with gesture so that learners can use their bodies (see Johnson, 1987) as an extension of their mind to help them learn and mediate their own performances in an L2. The advantage of introducing gesture as a pedagogical tool is that it is more portable than a SCOBA and as such would enable learners to transport conceptual meanings in a more efficient way than via a separate graphic depiction.

I have only been able to paint the history of SCT-L2 research with the broadest of brush strokes. The work is fleshed out in more chronological detail in Lantolf and Beckett (2009). The interested reader can also explore the searchable online bibliography on SCT-L2 research at http://language.la.psu.edu/SCTBIB/, which currently contains over 600 entries.

References

Ableeva, R. (2010). Dynamic assessment of listening comprehension in L2 French. Unpublished PhD dissertation. The Pennsylvania State University. University Park, PA.

Aljaafreh, A. and Lantolf, J. P. (1994). Negative feedback as regulation and second language learning in the zone of proximal development. The Modern Language Journal, 78, 465–483.

Antón, M. (2009). Dynamic assessment of advanced language learners. Foreign Language Annals, 42, 576–598.

Ausubel, D. P. (1970). Reception learning and the rote-meaningful dimension. In E. Stones (Ed.), Readings in educational psychology. Learning and teaching (pp. 193–206). London: Methuen.

Centeno-Cortés, B. (2003). Private speech in the acquisition of Spanish as a foreign language. Unpublished PhD dissertation. The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Centeno-Cortés, B. and Jiménez-Jiménez, A. (2004). Problem-solving tasks in a foreign language: The importance of the L1 in private verbal thinking. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14, 7–35.

Choi, S. and Lantolf, J. P. (2008). The representation and embodiment of meaning in L2 communication: Motion events in speech and gesture in L2 Korean and L2 English speakers. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30, 191–224.

Cole, M. and Engeström, Y. (1993). A cultural-historical approach to distributed cognition. In G. Solomon (Ed.), Distributed cognitions. Psychological and educational considerations (pp. 1–46). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crookes, G. (1998). On the relationship between second and foreign language teachers and research. TESOL Journal, 7(3), 6–11.

Danesi, M. (2008). Conceptual errors in second-language learning. In S. De Koop and T. De Rycker (Eds.), Cognitive approaches to pedagogical grammar (pp. 231–256). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Davydov, V. V. (2004). Problems of developmental instruction. A theoretical and experimental psychological study. Translated by Peter Moxhay. Moscow: Academiya Press.

DeKeyser, R. M. (1998). Beyond focus on form: Cognitive perspectives on learning and practicing second language grammar. In C. Doughty and J. Williams (Eds.), Focus on form in second language acquisition (pp. 42–66). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

de Guerrero, M. (2005). Inner speech—L2: Thinking words in a second language. New York: Springer.

Donato, R. (2004). Collective scaffolding in second language learning. In J. P. Lantolf and G. Appel (Eds.), Vygotskian approaches to second language research (pp. 33–56). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Ellis, R. (2006). Current issues in the teaching of grammar: An SLA perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 40, 83–7.

Ellis, R., Loewen, S., Elder, C., Erlam, R., Philp, J., and Reinders, H. (2009). Implicit and explicit knowledge in second language learning, testing and teaching. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Erlam, R. (2008). What do researchers know about language teaching? Bridging the gap between SLA research and language pedagogy. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 2, 253–267.

Ferreira, M. and Lantolf, J. (2008). A concept-based approach to teaching writing through genre analysis. In J. P. Lantolf and M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and second language teaching. (pp. 285–320). London: Equinox.

Frawley, W. and Lantolf, J. P. (1985). Second language discourse: A Vygotskyan perspective. Applied Linguistics, 6, 19–44.

Gergely, G. and Csibra, G. (2007). The social construction of the cultural mind. Imitative learning as a mechanism of human pedagogy. In P. Hauf and F. Försterling (Eds.), Making minds. The shaping of human minds through social context (pp. 241–257). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Gibbons, P. (2003). Mediating language learning: Teacher interactions with ESL students in a content-based classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 37, 247–273.

Goldin-Meadow, S., Cook, S. W., and Mitchell, Z. A. (2009). Gesturing gives children new ideas about math. Psychological Science, 20, 267–272.

Grabois, H. (1997). Love and power. Word association, lexical organization and second language acquisition. Unpublished PhD dissertation. Cornell University, Ithaca, NY.

Guk, I. and Kellogg, D. (2007). The ZPD and whole class teaching: Teacher-led and student-led interactional mediation of tasks. Language Teaching Research, 11, 281–299.

Gullberg, M. (in press). Language-specific encoding of placement events in gestures. In E. Pedersen and J. Bohnemeyer (Eds.), Event representations in language and cognition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haenen, J. (1996). Piotr Gal'perin: Psychologist in Vygotsky's footsteps. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Hammerly, H. (1982). Synthesis in language teaching: An introduction to linguistics. Blaine, WA: Second Language Publications.

Haught, J. and McCafferty, S. G. (2008). Embodied language performance: Drama and the ZPD in the second language classroom. In J. P. Lantolf and M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (pp. 139–162). London: Equinox.

Johnson, M. (1987). The body in the mind. The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Karpov, Y. V. (2003). Vygotsky's doctrine of scientific concepts: Its role for contemporary education. In A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. S. Ageyev, and S. Miller (Eds.), Vygotsky's educational theory in cultural context (pp. 39–64). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lantolf, J. P. (1997). The function of language play in the acquisition of L2 Spanish. In W. R. Glass and A. -T. Perez-Leroux (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on the acquisition of Spanish. Vol 2: Production, processing and comprehension (pp. 3–24). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Lantolf, J. P. (2003). Intrapersonal communication and internalization in the second language classroom. In A. Kozulin, B. Gindis, V. S. Ageyev, and S. Miller (Eds.), Vygotsky's theory of education in cultural context (pp. 349–370). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lantolf, J. P. (2010). Minding your hands: The function of gesture in L2 learning. In R. Batestone (Ed.), Sociocognitive perspectives on language use and language learning (pp. 131–150). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lantolf, J. P. (2011). Integrating sociocultural theory and cognitive linguistics in the second language classroom. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research on second language teaching and learning vol. II (Second Edition) (pp. 303–318). New York: Routledge.

Lantolf, J. P. and Beckett, T. (2009). Research timeline for sociocultural theory and second language acquisition. Language Teaching, 42(4), 1–19.

Lantolf, J. P. and Poehner, M. E. (2004). Dynamic assessment of L2 development: Bringing the past into the future. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1, 49–72.

Lantolf, J. P. and Poehner, M. E. (Eds.). (2008). Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages. London: Equinox.

Lantolf, J. P. and Poehner, M. E. (2011). Dynamic assessment in the classroom: Vygotskian praxis for L2 development. Language Teaching Research, 15, 1–23.

Lantolf, J. P. and Poehner, M. E. (2009–2011). Computerized dynamic assessment of language proficiency in French, Russian and Chinese. Research project funded by a grant from the International Research Studies of the U.S. Department of Education Title VI program. Grant number P017A080071.

Lantolf, J. P. and Thorne, S. L. (2006). Sociocultural theory and the genesis of second language development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Lantolf, J. P. and Yáñez-Prieto, C. (2003). Talking yourself into Spanish: Intrapersonal communication and second language learning. Hispania, 86, 97–109.

Lee, J. (2006). Talking to the self: A study of the private speech mode of bilinguals. Unpublished PhD dissertation. University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin.

Lee, H. (in progress). A concept-based approach to second language teaching and learning: Cognitive linguistics-inspired instruction of English phrasal verbs. Ph.D. dissertation. The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.

Levitin, K. (1982). One is not born a personality. Profiles of Soviet education psychologists. Moscow: Progress Press.

Littlemore, J. and Low, G. (2006). Figurative thinking and foreign language learning. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Loewen, S. and Philp, J. (2006). Recasts in the adult English L2 classroom: Characteristics, explicitness, and effectiveness. The Modern Language Journal, 90, 536–556.

Long, M. (2007). Problems in SLA. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Marx, K. (1978) Theses on feuerbach. In R. C. Tucker (Ed.), The Marx-Engels reader (Second Edition) (pp. 143–145).

McNeill, D. (2005). Gesture and thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Nassaji, H. and Swain, M. (2000). A vygotskian perspective on corrective feedback in L2: The effect of random versus negotiated help on the learning of English articles. Language Awareness, 9, 34–51.

Negueruela, E. (2003). A sociocultural approach to the teaching-learning of second languages: Systemic-theoretical instruction and L2 development. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation. The Pennsylvania State University. University Park, PA.

Negueruela, E., Lantolf, J. P., Jordan, S. R. and Gelabert, J. (2004). The “private function” of gesture in second language communicative activity: A study of motion verbs and gesturing in English and Spanish. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 14, 113–147.

Negueruela, E. (2008). Revolutionary pedagogies: Learning that leads (to) second language development. In J. P. Lantolf and M. E. Poenher (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (pp. 189–227). London: Equinox.

Newman, D., Griffin, P., and Cole, M. (1989). The construction zone: Working for cognitive change in school. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Newman, F. and Holzman, L. (1993). Lev Vygotsky: Revolutionary scientist. London: Routledge.

Norris, J. M. and Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quantitative meta-analysis. Language Learning, 50, 417–528.

Ohta, A. S. (2001). Second language acquisition processes in the classroom: Learning Japanese. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Pavlenko, A. and Lantolf, J. P. (2000). Second language learning as participation and the (re) construction of selves. In J. P. Lantolf (Ed.), Sociocultural theory and second language learning (pp. 155–178). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Poehner, M. E. (2007). Beyond the test: L2 dynamic assessment and the transcendence of mediated learning. The Modern Language Journal, 91, 323–340.

Poehner, M. E. (2008). Dynamic assessment: A Vygotskian approach to understanding and promoting L2 development. Berlin: Springer.

Poehner, M. E. (2009). Group dynamic assessment: Mediation for the L2 classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 43, 471–492.

Robinson, P. and Ellis, N. (2008). Conclusion: Cognitive linguistics, second language acquisition and L2 instruction—issues for research. In P. Robinson and N. Ellis (Eds.), Handbook of cognitive linguistics and second language acquisition (pp. 489–545). New York: Routledge.

Sanchez Vazquez, A. (1977). The philosophy of Praxis. London: Merlin Press.

Saville-Troike, M. (1988). Private speech: Evidence for second language learning strategies during the “silent period”. Journal of Child Language, 15, 567–590.

Sewny, V. D. (1945). The social theory of James Mark Baldwin. New York: King's Crown Press.

Slobin, D. I. (1996). From “thought and language” to “thinking for speaking”. In S. Gumperz and S. Levinson (Eds.), Rethinking linguistic relativity (pp. 70–96). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Slobin, D. I. (2003). Language and thought online: Cognitive consequences of linguistic relativity. In D. Gentner and S. Goldin-Meadow (Eds.), Language in mind: Advances in the study of language and thought (pp. 157–192). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Smagorinsky, P. (2001). Rethinking protocol analysis from a cultural perspective. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 21, 233–245.

Stam, G. (2008). What gestures reveal about second language acquisition. In S. G. McCafferty and G. Stam (Eds.), Gesture. Second language acquisition and classroom research (pp. 231–256). New York: Routledge.

Swain, M. (2006). Languaging, agency and collaboration in advanced second language proficiency. In H. Byrnes (Ed.), Advanced language learning. The contribution of Halliday and Vygotsky (pp. 96–108). London: Continuum.

Swain, M. and Lapkin, S. (2002). Talking it through: Two French immersion learners’ response to reformulation. International Journal of Educational Research, 37, 285–304.

Swain, M., Lapkin, S., Knouzi, I., Suzuki, W., and Brooks, L. (2009). Languaging: University students learn the grammatical concept of voice in French. The Modern Language Journal, 93, 5–29.

Talyzina, N. F. (1981). The psychology of learning. Moscow: Progress Press.

Thorne, S. L., Reinhardt, J., and Golombek, P. (2008). Mediation as objectification in the development of professional academic discourse: A corpus-informed curricular innovation. In J. P. Lantolf and M. E. Poehner (Eds.), Sociocultural theory and the teaching of second languages (pp. 256–284). London: Equinox.

Tocalli-Beller, A. and Swain, M. (2005). Reformulation: the cognitive conflict and L2 learning it generates. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 15, 5–28.

Tomasello, M. (1999). The cultural origins of human cognition. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Valsiner, J. (2000). Culture and human development: An introduction. London: Sage.

Vygotsky., L. S. (1926/2004). The historical meaning of the crisis in psychology: A methodological investigation. In R. W. Rieber and D. K. Robinson (Eds.), The essential Vygotsky (pp. 227–344). New York: Kluwer/Plenum.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, and E. Souberman (Eds.), Mind in society. The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1987). The collected works of L. S. Vygotsky. Volume 1. Problems of general psychology. Including the volume Thinking and Speech (R. W. Reiber and A. S. Carton (Eds.)). New York: Plenum Press.

Watanabe, Y. (2004). Collaborative dialogue between ESL learners of different proficiency levels: Linguistic and affective outcomes. Unpublished M.A. thesis. OISE, University of Toronto.

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic inquiry: Toward a sociocultural practice and theory of education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (1998). Mind as action. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wertsch, J. V. (2007). Mediation. In H. Daniels, M. Cole, and J. V. Wertsch (Eds.), The Cambridge companion to Vygotsky (pp. 178–192). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Whitley, M. S. (1986). Spanish/English contrasts. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Yáñez-Prieto, C. M. (2008). On literature and the secret art of invisible words: Teaching literature through language. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA.