7

Linguistic approaches to second

language morphosyntax*

Donna Lardiere

Introduction

The acquisition of the grammar—the morphology and syntax—of a second language (L2) lies at the heart of the study of second language acquisition (SLA) and consequently has generated, along with hundreds of studies, much heat as well as light. The study of L2 grammatical development, especially within the generative grammar tradition, proceeds from a core assumption shared by nearly all formal acquisitionists that an understanding of exactly what is to be acquired and how it is mentally represented is necessary in order to understand how it could come to be acquired (Chomsky, 1986a; Gregg, 1989, 1996). For this reason, most researchers who study L2 grammatical development in depth rely at least to some extent on highly articulated theoretical models of language form and its relation to meaning. In actual practice, this has meant that Chomsky's (1981) Principles and Parameters (P&P) framework, including subsequent revisions that have led to a radical theoretical overhaul known as the Minimalist Program (Chomsky, 1995a, 2001), has served as the linguistic basis for much of the work done in L2 morphosyntax and syntax over the past three decades. This chapter, therefore, reviews some of the key concepts and findings resulting from research in that framework, as well as touching on some of the different directions the study of the L2 acquisition of morphosyntax has more recently taken.

Core issues in historical context

Universal grammar

It is widely accepted that all normal children are ultimately successful at acquiring their native language(s). Moreover, native speakers of a language end up with a richer, more abstract system of knowledge than can be induced from the linguistic evidence directly observable in the environment, posing a learnability problem known as the poverty of the stimulus. In particular, they know that certain utterances may be ambiguous, or that others are impossible in their language. For example, English native speakers know that the sentence in (1) is ungrammatical, whereas (2) is perfectly fine:

(1) Which professor did John read the book about violent videogames had written?

(2) Which professor did John think had written the book about violent videogames?

Given that sentences like the one in (2) are present in the linguistic environment, what prevents an English language acquirer from overgeneralizing the movement of a question word to formulate questions like that in (1)? Or to put it another way, how does an English speaker learn that sentences like (1) are impossible? The answer given by Chomsky (1981, 1986a) was that such restrictions on possible wh-movement are not learned (and are certainly not taught); rather, they constitute part of the biological faculty of human language known as Universal Grammar (UG).1 Chomsky's position thus represents a strong nativist view of language acquisition.

Many researchers who work on syntactic acquisition are committed to some form of nativism, at least for first language (L1) acquisition. This is essentially the idea that human children are genetically equipped to acquire language. All approaches to human cognition recognize the existence of innately guided learning of some sort (Eckman, 1996, p. 398; O'Grady, 2008, p. 620). However, acquisition researchers disagree on the extent to which the genetic capacity for language acquisition consists of mechanisms and categories that are specific to language (special nativism) or rather consists of more generalized learning mechanisms, such as a capacity for detecting distributional patterns in the environment and formulating categories based on them (general nativism and emergentism).2

Researchers working within the UG theoretical framework have largely embraced special nativism, analyzing their data in terms of certain formal constructs such as grammatical features, categories, and restrictions on operations that are thought to be specifically dedicated to language. In this framework, the study of syntax over the past three decades has focused on discovering universal linguistic constraints on possible human language grammars, and the study of the acquisition of syntax is largely devoted to investigating the effects of these constraints in learners’ developing language.

What role, if any, does UG play in L2 acquisition, especially mature L2 acquisition? Note that, unlike native acquirers, it is not the case that all adult L2 learners, or even most of them, are ultimately successful (however we define “success.”) This lack of a uniformly successful outcome, including the observation that L2 performance is often persistently variable in ways that L1 performance is not, has led many researchers to the conclusion that SLA, particularly adult SLA, is qualitatively “fundamentally” different from L1 acquisition, and that acquisition is based instead on general problem-solving abilities (Bley-Vroman, 1989, 2009; see also Clahsen and Muysken, 1986; Felix, 1985; Meisel, 1997; Newmeyer, 1998, among others).

Nonetheless, L2 learners—especially those who are immersed in the target language environment—are exposed to the same kind of linguistic stimuli as native speakers and thus also face a poverty of the stimulus problem (Schwartz and Sprouse, 2000; White, 1989, 2003). Therefore, one of the earliest and most enduring questions of the field of L2 syntax has been whether it is possible for mature L2 learners to end up with abstract knowledge of a second language that could not be induced from particular sets of utterances in the environment. If so, and if it could also be shown that such knowledge could not have been transferred from the L1, then researchers could conclude that UG constraints were still operational in mature SLA.

White (2003, p. 22) emphasizes that it is not necessary for L2 learners to acquire knowledge that is nativelike in all respects in order to demonstrate poverty of the stimulus effects which implicate continued access to UG constraints. In other words, even if learner interlanguages (ILs) are non-targetlike, they still exhibit many of the domain-specific properties of UG-constrained natural language grammars. However, even if it could be shown that the developing L2 grammar is UG-constrained, it is nonetheless striking that mature L2 learners often still ultimately fail to achieve nativelike performance in the target language. This is true even when the relevant stimuli in question (such as verbal inflections) are abundantly present in the linguistic environment and thus do not necessarily pose a learnability problem. R. Hawkins (2001a) argues that, in contrast to studies based on poverty of the stimulus that seek evidence for the fundamental similarities of L1 and L2 grammatical representations, the study of the differences between L1 and L2 acquisition within linguistic-based approaches could lead to a better understanding of the nature of the interaction or “interfaces” between UG and other components of the mind. This view reflects a shift that has taken place in generative SLA studies since the early 1990s, away from an earlier primary focus on “access to UG” debates, to seeking a greater understanding of the nature of IL grammatical representations in their own right, including potential sources of persistent morphosyntactic variability.

Principles and parameters theory

Because UG is a theory about the innate biological capacity for human language, its principles are invariant and apply to all human natural languages, delimiting the range of possible human languages. But the grammars of natural languages obviously differ from each other in striking ways, such as their sentential word orders, whether certain elements (such as subject pronouns) can be dropped, whether certain features are expressed inflectionally, whether thematic relations are determined by word order or case-marking, and so on. Interestingly, comparative typological research (e.g., Greenberg, 1963; see Biberauer, 2008 for a historical overview) strongly suggests that certain grammatical patterns and correlations recur throughout the world's languages, and that cross-linguistic syntactic differences are not limitless or random. This empirical observation has been captured within a UG framework by the notion of parameters. Parameters are considered to be an innately predetermined finite set of “limited options” whose values are fixed by the learner on the basis of having been exposed to some utterances of a particular language known as primary linguistic data (PLD). Together, principles and parameters were originally hypothesized to tightly restrict the range of cross-linguistic syntactic variation as well as the range of possible grammatical hunches entertained by child language learners, helping to account for the rapidity and relative ease with which children acquire language.

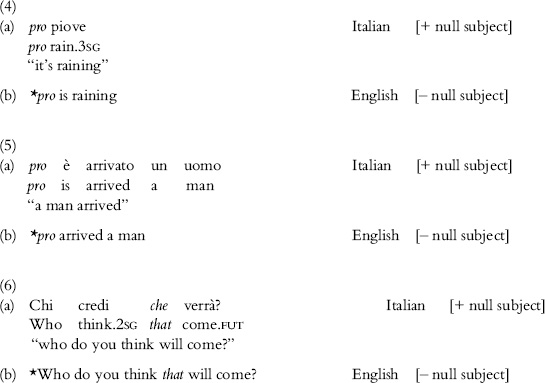

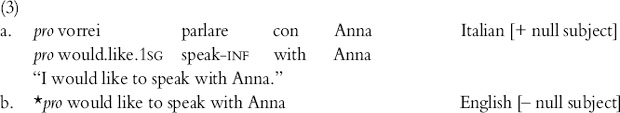

For example, one of the proposed principles of UG is that all sentences must have subjects.3 However, languages differ in whether subjects must be expressed overtly or not—a parameterized option dubbed the Null Subject Parameter (Rizzi, 1982, 1986). In languages that select the (+) value of the parameter, such as Italian, the pronominal subject of a finite clause may consist of a null pronoun pro, whose person/number features are instead identifiable by verbal agreement morphology (3a). On the other hand, in languages that select the (–) null subject parameter value, such as English, overt pronouns are required (3b):

Some properties that have been correlated with the positive setting of the null subject parameter include the possibility of null expletive subjects (4a), post-verbal subject inversion (5a), and the presence of an overt complementizer in subordinate clauses from which subject wh-movement has occurred (6a); languages with the negative setting, such as English, prohibit these:

At first glance, the contrasts shown above appear superficially unrelated to the option of having null subjects. There is nothing in the input, for example, that could indicate to a child learning English that (6b) is ruled out, especially since similar-sounding sentences like “Who do you think that Anna saw?” are acceptable. Yet, English native speakers do come to know this. Such associated properties, sometimes referred to as the “deductive consequences” of a parameter, were hypothesized to play a powerful role in language acquisition, in that learning one of the properties would automatically result in the acquisition of the others.

Parameter theory initially held great promise for formally describing the potential learning challenges facing the L2 acquirer as well. Since learners bring to the SLA task a fully developed L1 grammar with parameter values already fixed to their L1 settings, success or failure of grammatical acquisition might be attributed to learners’ (in)ability to reset parameters from the L1 values to those of the L2. Moreover, researchers have wondered whether the cluster of properties associated with selecting a new parameter value would also automatically be acquired as they were hypothesized to for L1 acquisition. We return to this issue in the section entitled Empirical Verification.

Parameters in the minimalist program. Under early versions of P&P theory, as mentioned above, a limited number of parameters were hypothesized to be associated with invariant core principles of UG. The problem, as Chomsky (2005, p. 8) discusses, is that if language acquisition were just a matter of selecting among relatively few options attached to the invariant core principles of UG, then UG itself would have to be “rich and highly articulated.” However, as wider ranges of languages were investigated and compared, it became clear that their properties could not be accommodated within relatively few, broadly general options. Instead, theories that could account for the data had to impose increasingly “varied and intricate” conditions that were necessarily formulated in language-specific terms that seemed unlikely to be built into the human genome.

The P&P framework, in attempting to move toward principles of ever-broader generality, represented a “radical break” from previous grammatical theories that relied on language-specific rules to account for particular grammatical constructions (Chomsky, 1995a, p. 170, 1995b, p. 388). The Minimalist Program (Chomsky, 1995a, 2001) reflects a sharply intensified commitment to this ideal. It is an attempt to achieve maximum—in fact, universal—generality in its characterization of an invariant computational component of the human language faculty, using the fewest possible language-specific principles. With regard to language acquisition, Chomsky (2007, p. 4) observes that, whereas pre-Minimalist generative approaches asked “How much must be attributed to UG to account for language acquisition?,” recent Minimalist approaches instead ask “How little can be attributed to UG while still accounting for the variety of I-languages attained?”

Under Minimalism, the locus of such “varied and intricate” cross-linguistic grammatical differences has been shifted to the lexicon—in particular, to grammatical features (such as [±wh], [±past], or [±definite]).These features are considered part of UG—specifically, part of a universal feature-set or inventory. Since not all languages make use of every feature in the inventory, “parameter-setting” within this framework consists of the learner identifying and selecting only that subset of features used in the target language. The selected features are assembled into language-specific morpholexical items, including free and affixal forms (e.g., whether, -ed, the in English). In other words, the burden of accounting for the acquisition of the features, categories and constraints of particular languages is largely shifted from the genetic endowment to language-independent mechanisms of data processing and computational efficiency (Chomsky, 2005).

For SLA, the learner's task is still couched in terms of the need to acquire the parameter values of the L2. In Minimalist, feature-based terms, this means that the learner must identify, select, and redistribute the required features among the lexical items of the L2. Recall that the learner brings to this task an already fully developed language in which the L1 features have already been selected and “packaged” into L1-specific grammatical categories and lexical items. In the following section, we consider more closely the role of prior-language knowledge in this process.

The role of L1 knowledge in acquiring the L2 grammar

Except for a relatively brief period (mainly through the 1970s) when the role of transfer was downplayed in favor of “natural order” approaches based primarily on morpheme-order studies,4the role of prior-language knowledge has been recognized by most generative researchers as a critically important factor in accounting for L2 grammatical acquisition. Within the L2 morpho-syntax literature of the past two decades, two broad questions regarding transfer clearly emerge: (1) To what extent (if any) does the grammar of the L1 constitute the initial “departure point” for a learner's assumptions and representation of the L2 grammar? and (2) To what extent (if any) is ultimate attainment of the L2 circumscribed by the categories and features of the L1?

Question (1) was addressed in the 1990s in the context of several studies examining the nature of the L2 initial state (e.g., Eubank, 1996; Schwartz and Sprouse, 1996; Vainikka and Young-Scholten, 1994, 1996). Assuming the existence of functional categories (such as case, tense, aspect, definiteness, etc.) in fully developed native-speaker grammars, the specific question asked was: At what point does knowledge of these categories become available to the learner? Do the functional categories and features of the L1 transfer, so that the L2 learner starts out with all (and only) those categories that make up the L1?5

Question (2) is important particularly in case the L1 has not selected a particular feature that is required by the L2: Are those previously unselected features still available? This question (at least tacitly) assumes that a constraining role of the L1 may persist through stages beyond the initial state, including the so-called “steady-” or end-state of acquisition. We briefly consider each of these questions in turn.

Partial vs. full transfer in the initial L2 state. Given that linguistically mature native speakers know which functional categories and features are required for producing and interpreting well-formed sentences in their L1, how much and which parts of this knowledge are used for constructing the grammar of the L2? And how can we tell? In other words, what counts as evidence for such knowledge?

The most conservative hypotheses about knowledge of the grammatical categories of the L2 are those which assume that a particular morphosyntactic category is not established in the learner's grammatical representation until the functor morphemes associated with that category are systematically produced at a certain criterial level in obligatory contexts. (Some researchers, following Brown's (1973) L1 study, employ a 90% criterion, but for L2 studies, the criteria vary and are typically relaxed somewhat.) Vainikka and Young-Scholten (1994, 1996) observed that naturalistic Turkish or Korean L1 speakers learning L2 German omitted many functional elements in early stages of their spoken German, or produced them only variably (at a rate lower than 60% suppliance in obligatory contexts), or produced default forms such as infinitive-inflected verbs where finite forms were required. They therefore hypothesized that only the open-class lexical categories of the L1 such as noun phrases (NPs) verb phrases (VPs) (including their subject-object-verb linear word order) carried over to the L2.

Under this view, dubbed the Minimal Trees Hypothesis (and in more recent work, Organic Grammar), the syntactic categories of the learners’ L1, including those associated with case, tense, and subject-verb agreement (for the Turkish speakers), were argued not to transfer, even though learners obviously have knowledge of these categories in their L1. These would be acquired instead as a result of learning the language-specific morphemes associated with each category in the target L2. Moreover, Vainikka and Young-Scholten proposed that the acquisition of functional categories proceeded gradually and implicationally, such that “lower” categories in the phrase-structure hierarchy were acquired in successive stages before “higher” ones; that is, inflectional phrase (IP) related categories were acquired before complementizer phrase (CP) related ones. Note that, in principle, under Vainikka and Young-Scholten's approach there is no impediment to the eventual attainment of nativelike UG-constrained syntactic knowledge of the L2.

In a direct challenge to the Minimal Trees Hypothesis, Schwartz and Sprouse (1996) proposed a full transfer account, called the Full Transfer/Full Access Hypothesis (FT/FA), in which they argued that the morphosyntactic categories and features of the L1 grammar in its entirety constitute the initial state of the L2. In other words, learners initially assume that the L2 includes all the functional projections (e.g., CP, IP, determiner phrases (DP)) and their associated feature specifications (e.g., for tense, aspect, case, agreement, definiteness, etc.) of the L1, even though they have not yet acquired the specific functional morphemes that express these categories in the L2.

The FT/FA hypothesis does not imply that a learner is somehow stuck with the L1 grammar. Restructuring of the IL grammar is input-driven, occurring wherever there is a mismatch between the initial (L1) representation and what is needed to parse or accommodate the L2 input. Thus, arguments against FT/FA suggesting that a learner's L1 has little influence on syntactic aspects of the L2 that are readily accessible in the input (such as basic word order; see, e.g., Ellis, 2008, p. 362) are misconceived, especially for developmental stages beyond the initial state. According to Schwartz and Sprouse, there is, however, one circumstance under which a learner might indeed become stuck, and that is just in case (a) a particular parameter or feature specification has been set to a different value in the L1 than that required by the L2, and (b) there is no positive evidence in the input to force restructuring to the L2 value. In that case, assuming full transfer, the correct L2 value might never be acquired. (See Lardiere, 2007, pp. 216–229 for discussion of this issue.)

Note the similarities and differences between these hypotheses in terms of the types of evidence used to support their developmental claims. Both approaches assume that the productive use by the learner of functional elements (such as case, agreement, and finite-tense marking, the use of auxiliaries, complementizers, determiners, etc.) indicates that the corresponding functional syntactic categories have been acquired. In addition, functional categories in both approaches serve as landing sites for syntactic movement (such as wh-movement). Therefore, any evidence for syntactic movement in the learner IL, such as subject-auxiliary inversion in English questions or finite-verb raising in main clauses in German, may also be taken as evidence that higher functional structure is present. This creates something of an analytical dilemma for researchers examining early developmental stages in which grammatical morphology is variably omitted but constituents such as finite verbs in German or wh-question words in English appear in their correct (i.e., displaced) positions. Additionally, because the acquisition of a functional category higher in the clausal hierarchy is generally assumed to entail the acquisition of any lower categories as well, a similar kind of dilemma results when acquisition data appear to show that a learner produces the elements of a higher category (e.g., wh-question words, presumed to be in CP) well before producing (criterial) levels of grammatical morphemes associated with lower ones (e.g., correct subject-verb agreement marking, associated with IP). Yet, such data are common. For example, Gavruseva and Lardiere (1996) and Lardiere (2000) showed in two different long-itudinal case studies that evidence for CPs was present despite the absence of inflectional morphology associated with IPs.

Each approach addresses these dilemmas somewhat differently, relying on contrasting views of the relation between morphology and syntax, or more precisely, between knowledge of morphemes—the language-specific realization of a functional feature (such as English -ed, the, or -s)—vs. knowledge of the abstract feature itself (such as PAST, DEFINITE, PLURAL). Schwartz and Sprouse argue that it is the latter—that is, knowledge of abstract morphosyntactic categories—that transfers. On the other hand, Vainikka and Young-Scholten believe that knowledge of the abstract grammatical properties of the L2 can only be acquired from actual, overt L2 morphemes, which need to be learned before a corresponding abstract category can be inferred and projected in the L2 syntax. (Neither approach assumes that actual morphemes transfer.) The Vainikka and Young-Scholten model, therefore, requires a more ad hoc sort of syntactic structure—one that is underspecified and more flexible with respect to particular functional categories but that can nonetheless still provide structural landing sites for displaced constituents in earlier stages of development.

The persistence of L1 influence in morphosyntactic development. As mentioned above, cross-linguistic “parametric” variation in the Minimalist Program arises because languages select different features and/or assemble them differently within their particular lexicons. For SLA, therefore, “parameter-resetting” requires that the learner (re)select and (re)assemble the features of the morphemes of the target language. Can L2 learners successfully accomplish this? In some recent proposals, prior-language knowledge plays a persistent and even deterministic role in the ultimate outcome of grammatical development in the L2.

One prominent feature-based line of inquiry attempts to predict the precise conditions under which parameter-resetting will fail, due to a mismatch between L1 and L2 feature selection. Referred to variously as the Failed Functional Features Hypothesis (Hawkins and Chan, 1997), the Representational Deficit Hypothesis (Hawkins, 2003; Hawkins and Liszka, 2003), or more recently, the Interpretability Hypothesis (Hawkins and Hattori, 2006; Tsimpli and Dimitrakopoulou, 2007—the cover term I adopt here to represent the approach), the specific prediction is that, in cases where a particular morphosyntactic feature is required in the L2 but was not previously activated in the learner's L1, that feature will no longer be acquirable, due to critical period effects. In the most recent studies, an additional condition is that the feature in question be uninterpretable—that is, a purely formal feature with no semantic content of its own, such as those that trigger movement and/or enter into agreement relations. (We return to an example below.)

Another type of approach that addresses ultimate acquirability and the persistent role of L1 influence in SLA is the Feature Reassembly Hypothesis of Lardiere (2008, 2009a). Under this proposal, difficulty in L2 grammatical acquisition is related to the extent to which formal features that have already been “packaged” or assembled into certain morphemes in the L1 must be isolated and redistributed among different morpholexical items in the L2. Additionally, the learner must acquire knowledge of the appropriate conditioning environment for expressing a certain feature, which may sharply differ from that of the L1 (e.g., what constitutes an obligatory context in the L1 vs. the L2).

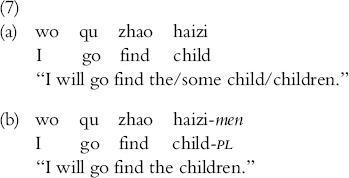

To illustrate, consider the case of a native (Mandarin) Chinese speaker acquiring plural-marking in L2 English, or vice-versa. Both English and Chinese have morpholexical means for indicating plurality—the suffixes -s and -men respectively.6,7 In English, plural-marking is obligatory on count nouns that denote “more-than-one” referents, especially in quantified contexts such as several books or three students. However, plural-marking in English is indiscriminate with regard to animacy (e.g., books vs. students) or definite/specific reference (e.g., any students vs. those students). In Chinese, on the other hand, plural-marking is optional (except on plural personal pronouns, where it is required) and quite restricted. It is explicitly prohibited in certain contexts in which it is required in English, namely, quantified contexts (e.g., *san-ge xuesheng-men “three-CL student-PL”); it is typically only marked on nouns denoting humans; and, notably unlike English, its use on a noun requires that noun to be interpreted as definite. Thus, compare the Chinese sentences shown below in (7). Whereas (7a) is a perfectly good sentence in Chinese that is simply neutral or underspecified with regard to number and definiteness, (7b) is specified with regard to both. The plural-marked noun haizi-men “children” in (7b) must be interpreted as plural and definite; it cannot, for example, mean “I will go find (some) child(ren)” (examples from Li, 1999, p. 78):

Although both Chinese and English could be argued to “parametrically select” the feature [+plural] and both have overt morphemes for expressing it, learners must still distinguish between optional vs. obligatory application, and consider additional syntactic and semantic restrictions (e.g., [±human], [±definite], co-occurrence with quantifiers). Grammatical acquisition, in other words, requires redistributing abstract features among the relevant morpheme(s) in the target language and learning the precise conditions under which these can or must (or must not) be expressed. There is nothing ultimately preventing a learner from accomplishing this; that is, unlike the Interpretability Hypothesis, successful acquisition of both interpretable and uninterpretable features is in principle possible, but is likely to be more difficult in cases where the features in question are configured quite differently and expressed under quite different grammatical and/ or discourse conditions. Because of this, the Feature-Reassembly approach offers less crisp predictions (of failure) than the Interpretability Hypothesis, but it is more compatible than parameter-setting models with the longstanding observation that for any given feature or category, any given learner's production of the corresponding inflection may be highly variable, and a learner's L2 grammatical idiolect may not exactly match that of either the native or the target language.

Finally, we consider another type of potentially persistent L1 influence on the acquisition (and certainly the spoken production) of grammatical morphemes in the L2—the effect of L1 phonology. The Prosodic Transfer Hypothesis of Goad and White (2004, 2006, 2008) proposes that L1 prosodic constraints may impede the spoken production of L2 functional morphemes, by restricting the kinds of phonological representations that can be built in the L2; as a result, L2 learners are sometimes forced to delete morphology or pronounce it in non-nativelike ways. At first glance, this proposal seems rather like a phonological equivalent to the morphosyntactic Interpretability Hypothesis, in that the (un)availability of L1 phonological structures plays a near-deterministic role in the attainment of L2 functional morphology. Goad and White, however, do not predict inevitable acquisition failure in cases where the prosodic representations required by the L2 are unavailable in the L1. Instead, they argue that, although acquisition will be more difficult, it is not impossible in cases in which L2 learners are able to “minimally adapt” appropriate pieces of their L1 prosodic structures in order to accommodate L2 requirements. However, representations that cannot be built from existing L1 structures will indeed be impossible to acquire, leading to fossilization (Goad and White, 2006, pp. 246–247).

To summarize this subsection, the effect of prior-language knowledge—L1 transfer—on L2 grammatical development has long played a central role in SLA theorizing. The two main issues discussed here were the extent to which the L1 grammar constitutes the initial “departure point” for a learner's assumptions and representation of the L2 grammar, and the extent to which ultimate attainment of L2 knowledge is affected by persistent L1 influence. The first issue carries important implications for our understanding of when and how knowledge of grammatical features and categories in the L2 arises in the course of development; the second bears on our ability to predict and account for the eventual outcome of the developmental process.

Data and common elicitation measures

The different kinds of data elicitation methods used to study morphosyntactic acquisition in SLA depend on the specific research questions being asked, but serve the shared common purpose of illuminating the nature of learners’ L2 knowledge at particular stages of development. The grammatical systems of (all) language acquirers are part of their mentally represented idiolects and are largely inaccessible to direct inspection by researchers; therefore, conjectures about their nature must be indirectly inferred from observable performance.

The ability of learners to correctly produce grammatical morphemes (such as markers for case, tense/aspect, plurality, definiteness, negation, agreement, etc.) to some criterial degree in appropriate or obligatory contexts under real-time pressure in either naturalistic or experimental circumstances typically remains the standard for inferring that a learner has acquired the representation of morphosyntactic categories and features associated with the morphemes, along with the contextual conditions for their expression. There are many kinds of procedures for eliciting production data, ranging from collecting and transcribing spontaneous conversational and interview data, to narrative story or film retelling, to the use of tasks specifically designed to elicit targeted grammatical structures (for example, relative clauses). The latter are particularly useful in cases where the targeted elements might not be readily forthcoming in more naturalistic situations, due to lower frequency of occurrence or to learner avoidance. Such tasks include elicited imitation, picture description, sentence combining, and translation, among others. Some tasks, such as translation from the L2 into the L1, can be used to investigate L2 comprehension as well.

Furthermore, there are many circumstances in which researchers would like to know if learners have acquired knowledge of what is not possible in the L2, such as knowledge of the restrictions on wh-movement discussed earlier. For obvious reasons, such data do not occur in the L2 linguistic environment (the PLD) and the use of a production task alone would be uninformative and/or inappropriate. Additionally, learners might prefer one structure over another without ever indicating whether a particular unproduced structure or unselected task item is in fact ruled out by their IL grammar. In these cases, researchers are apt to make use of some type of acceptability judgment task (also commonly referred to as a grammaticality judgment task).8 The ability to reject ungrammatical sentences is considered stronger evidence of knowledge of linguistic constraints and constitutes the primary rationale for the task.

Both the validity and reliability of acceptability judgment tasks have been widely discussed and criticized, although an in-depth discussion is beyond the scope of this chapter. (See Birdsong, 1989; Schütze, 1996; Sorace, 1996 for overviews and suggestions for improving the methodology.) In general, judgments by learners are clearly subject to extra-linguistic rating strategies unanticipated by the researcher (see Snyder, 2000 for discussion and examples). Nonetheless, with carefully designed studies, acceptability judgment tasks can provide researchers with valuable insights about learner grammars.

Another task that is fruitfully used especially to investigate the interpretive consequences of (morpho)syntactic relations and operations is the truth-value judgment task. Learners are presented with a brief context or scenario and then asked to make a simple “true” or “false” judgment about whether a statement accurately describes some aspect of the preceding context. Typically, the statement incorporates some syntactic structure that the learner must be able to parse and interpret appropriately in order to respond correctly. The great advantage of this task is that, unlike acceptability judgment tasks, it does not require the learner to make a metalinguistic judgment about whether the statement in question is grammatical or not, but rather simply to build a semantic representation for it on which to base a “true” or “false” response in relation to the context.

Finally, let us briefly consider the use of online language processing tasks that make use of reaction or reading time (RT) measures. One such task is sentence-matching, in which either a grammatical or ungrammatical sentence is presented on a computer screen followed by another; the participant is asked to simply record as quickly as possible whether the two sentences match or not. Again, no metalinguistic judgments are required regarding acceptability; instead, the reaction time of the response is measured. The assumption is that if L2 learners take significantly longer to respond to ungrammatical rather than grammatical sentences (as has been demonstrated for native speaker (NS) controls), then it is because their IL grammar has (tacitly) detected the ungrammaticality and has taken longer to parse or build a representation for the ungrammatical sentence. If there is no significant difference in reaction time for ungrammatical vs. grammatical pairs of sentences, however, then the assumption is that the learner has not detected any ungrammaticality and—rather more controversially—therefore must not mentally represent the grammatical contrasts under investigation.

Proponents of RT studies point out that such tasks show whether or not some grammatical contrast has been fully “integrated” into the IL representation—that is, automatized, whereas judgment and production data are more susceptible to metalinguistic monitoring of explicit knowledge (e.g., Jiang, 2004, 2007). Other researchers urge caution, observing that interpreting the data are tricky. Gass (2001, p. 439), for example, suggests that, especially for lower-proficiency learners with slower reading times, the sentence-matching task “may represent little more than word-by-word matching” rather than actual reading and processing. Ultimately, the strongest support for claims about L2 grammatical knowledge will be based on convergent data from multiple sources and different kinds of tasks.

Empirical verification

In this section, we consider findings from data-based studies that have investigated some of the core issues presented above (Core issues in historical context). As mentioned earlier, there have been literally hundreds of studies investigating various aspects of the acquisition of morphology and syntax within a formal linguistic framework; space constraints prevent us from looking at more than a representative handful of these.

Access to UG? The question of whether the grammatical representations of mature L2 acquirers are in some sense epistemologically equivalent to those of native language acquirers is of enduring interest for researchers seeking to understand the nature of L2 knowledge and the contribution such understanding could make to our overall picture of the components of human cognition. Schwartz and Sprouse (2000, p. 156) write: “The leading question animating generative research on non-native language (L2) acquisition is, presumably, whether Interlanguage ‘grammars’ fall within the bounds set by UG, and if they do not, then just what their formal properties are.” Such studies are necessarily focused on testing predictions based on specific aspects of syntactic theory; however, the accumulated evidence amassed to date for a wide range of formal aspects of language suggests that knowledge of the essential formats of UG-constrained (morpho)syntactic representations (e.g., of hierarchical structure dependence, conditions on movement, knowledge of interpretive restrictions, the presence and acquirability of functional categories and features) remains intact in adult L2 acquisition (e.g., Anderson, 2008; Dekydtspotter and Sprouse, 2001; Dekydtspotter, 2001; Kanno, 1998; Lardiere, 1998; Martohardjono, 1993; Pérez-Leroux and Glass, 1999; White and Genesee, 1996; among many others). Carroll (2001, p. 107), though skeptical of a role for UG in SLA, observes that language is nonetheless apparently encoded in the “right” representational systems in the L2 as in the L1.

Empirical studies informed by formal linguistic theory are necessarily shaped by the details of a particular version of the theory in effect at the time of the study. As Schwartz and Sprouse (2000, p. 168) point out, the extent to which the conclusions of such studies are based on theory-internal technicalities is the extent to which they can also be undermined by revisions to that theory. They therefore advocate the investigation of clearcut poverty of the stimulus problems, for which positive evidence is unavailable either from the PLD or from properties of the L1, and for which attained knowledge thus necessarily implicates the availability of UG constraints regardless of changes to the “easily revisable details of particular hypotheses of specific syntactic theories.” One such investigation is the widely cited study by Martohardjono (1993), who tested L1 speakers of Chinese, Indonesian, or Italian acquiring L2 English on their knowledge of the ungrammaticality of sentences such as the earlier example in (1) repeated below as (8):

(8) *Which professor did John read the book about violent videogames had written?

Her results indicated that, like the NS controls, the L2 learners in all three L1 groups rejected these (“strong violation”) sentences at a significantly higher rate than more weakly ungrammatical (“weak violation”) sentences such as the one in (9):

(9) *Which professor did John think that had written the book about violent videogames?

This distinction between strong and weak violations was motivated within the Barriers (Chomsky, 1986b) framework of generative syntactic theory. As Schwartz and Sprouse (2000) discuss, although the technical details of syntactic theory have changed considerably in the meantime, the conceptual problem addressed by Martohardjono remains the same:

No matter how the constraints on [wh-]extraction are framed, there is a clear poverty-ofthe-stimulus problem involved in acquiring the distinction between strong and weak violations, since they both refer to essentially non-occurring syntactic patterns. ... The fact that Martohardjono's L2 acquirers display knowledge not only of the unacceptability of strong violations, but also the distinction between strong and weak violations, is a very strong indication that L2 development is constrained by UG. (p. 177)

Deductive consequences in parameter resetting? Recall from the section Principles and Parameters Theory that the various seemingly unrelated properties associated with particular parameter values— so-called “deductive consequences”— were hypothesized to play a powerful role in L1 acquisition; SLA researchers have been interested in learning whether these properties would also automatically be acquired if and when L2 learners managed to select the appropriate parameter value for the L2. The acquisition of the correct L2 setting of the Null Subject Parameter, including its associated cluster of properties (discussed earlier), has been studied intensively in generative SLA research, and we briefly review the main empirical findings here. Along with the [+null subject] setting, including the absence of expletive subject pronouns, such related properties include the possibility of post-verbal subjects, and the possibility of extraction of wh-subjects from embedded clauses with an overt complementizer. Not all studies tested all properties, but overall, the findings indicate an absence of the expected clustering effects in SLA.

Phinney (1987) and Tsimpli and Roussou (1991) found that, whereas L1 Spanish and Greek speakers (respectively) acquiring L2 English were likely to supply overt referential subject pronouns and/or reject null referential subject pronouns where required, they failed to do so with expletive subjects; that is, they incorrectly allowed null expletive subjects in English. White (1985, 1986) reported that L1 Spanish/Italian ([+null subject]) speakers were significantly less accurate than L1 French ([–null subject]) speakers in rejecting null subjects in L2 English and more likely to allow that-trace violations, suggesting L1 transfer, although both groups were highly accurate in correctly rejecting post-verbal subjects. Reviews by Hawkins (2001b, p. 206) and Carroll (2001, p. 164) of the available evidence to date point to the conclusion that the hypothesized cluster of properties associated with this parameter do not emerge as a cluster in L2 development.

More recently, Belletti and Leonini (2004) found that, whereas null pronominal subjects were available to L2 learners of Italian, the grammatical option of post-verbal subjects was significantly less so, again suggesting a dissociation. Furkóné Banka (2006) found that L1 Hungarian learners of L2 English were able to acquire overt subjects and the ability to reject post-verbal subjects, but they were not able to accurately reject that-trace violations, even at advanced-proficiency levels. Sauter (2002) undertook a two-year longitudinal study of nine Romance learners of English or Swedish and found that, although the related properties appeared to transfer as a cluster, they were never “unlearned”; that is, the parameter value was never reset. All nine learners persisted (to varying degrees) in producing utterances with missing pronominal subjects in main and subordinate clauses as well as post-verbal subjects, and Sauter concluded that they were unable to acquire previously unactivated options of UG.

To summarize, then, the majority of SLA studies that have tested the hypothesized clustering of deductive consequences associated with parameter setting in general and the Null Subject Parameter in particular indicate that such clustering effects remain empirically unverified, if not outrightly disconfirmed. Bley-Vroman (2009, p. 184) goes so far as to state that “in 20 years of SLA research, not a single study has convincingly demonstrated the sort of triggering and clustering that might be expected.” Moreover, as discussed in Lardiere (2009a, b; see also Carroll, 2001), within syntactic theory itself, the proposed clustering effects associated with most parameters have also failed over time to be empirically verified.9 Such clustering effects have now been largely abandoned as a necessary condition for acquisition within much P&P research, especially in so-called “microparametric” research that investigates fine-grained differences between related languages (e.g., Kayne, 2005, p. 6). Consequently, the notion of parameter-setting as a useful explanatory construct for (second) language acquisition must be reconsidered in light of these developments within linguistic theory.

More on wh-features. Let us consider empirical verification within another area that has been intensively investigated in SLA syntactic research—that of wh-movement and constraints on wh-movement. Such constraints are broadly referred to as subjacency constraints, and have often been used as a kind of test case to verify whether adult learners have UG-constrained syntactic knowledge. The study by Martohardjono (1993) discussed above is one example of how demonstrated knowledge of the distinction between strong and weak violations of constraints on wh-movement has led to the claim that adult learner ILs are indeed constrained by conditions that are both underdetermined in the target language PLD and unavailable from the L1, and therefore pose a genuine learnability problem.

Several other studies have been carried out in this area, with conflicting results. Some have found that L1 speakers of wh-in-situ languages have difficulty rejecting subjacency violations in English, and have concluded from this that principles of UG are inaccessible to adults (e.g., Bley-Vroman et al., 1988; Johnson and Newport, 1991; Schachter, 1989, 1990). Others have found evidence that subjacency-type constraints either still appear to be available or that they are simply not applicable because the (apparently) displaced wh-element may have instead been base-generated in clause-initial position or alternatively “scrambled” to that position via a different movement mechanism that is common in case-marking languages (see Belikova and White, 2009; Hawkins, 2001b for more thorough reviews of this literature). Although the latter type of claim is compatible with “access to UG” analyses, learner representations are nonetheless argued to be non-nativelike, because parameter-setting (in the form of [+wh] feature-selection mentioned earlier) fails. To illustrate, we briefly turn to a recent study that investigated the L2 knowledge of wh-movement constraints among Japanese-speaking learners of L2 English.

Hawkins and Hattori (2006) first observe that, in several previous studies, Japanese NSs acquiring L2 English appear able to converge on the same representation for wh-movement as English NSs on a number of different measures, such as targetlike wh-fronting and subject-auxiliary inversion, knowledge of the impossibility of contracting is to ’s in cases like Do you know where John is/*’s now?, the ability to distinguish grammatical from ungrammatical long-distance wh-questions involving strong and weak violations, and so on. These findings suggest that Japanese NSs are ultimately able to acquire sophisticated intuitions about English syntax despite the absence of an uninterpretable [+wh]-feature in Japanese. Hawkins and Hattori argue, however, that such convergence is only apparent. They found that, although there was no significant difference between Japanese speakers and English NS controls in accepting responses that did not violate any movement constraints, the Japanese were significantly more likely than the English NS controls to also accept sentences that did violate interpretive constraints on English multiple wh-questions such as Who did Sophie's brother warn Sophie would phone when? They concluded that the learner group was drawing on the grammatical possibility of scrambling in Japanese, which is arguably not subject to subjacency constraints (Saito and Fukui, 1998), and that they had not selected the required uninterpretable [+wh] feature in their L2 English, thus supporting the Interpretability Hypothesis discussed in the section The role of L1 knowledge in acquiring the L2 grammar. More generally, they caution against interpreting targetlike performance (found by many studies) as evidence that L2 speakers have the same underlying grammatical representations as native speakers or that their representations originate from the same source.

Note that the claim that the L1 Japanese speakers failed to reject violations in this study is not the same as arguing that they ultimately could not do so (say, if another group were more advanced than this group or if it could be established that their grammars were not yet endstate grammars), which is what the Interpretability Hypothesis requires. Therefore, Hawkins and Hattori are correct to claim that their results at this point are “consistent with” the hypothesis (p. 269). Moreover, this is an example of a study whose premises rest particularly heavily on theory-internal technical details, and the judgments obtained even from the English NS controls appear highly fragile. Thus, the conclusions from this and similar studies remain quite vulnerable to being undermined by ongoing revisions to Minimalist syntactic theory, as previously pointed out by Schwartz and Sprouse (2000). More recently, Belikova and White (2009) discuss this issue in particular relation to constraints on wh-movement. It is clear that the evidence for such constraints is underdetermined by the available PLD of the target language environment and acquiring them thus constitutes a genuine learnability problem. However, assuming the operation of the same few invariant computational principles in the grammars of all languages (as Minimalist theory now requires), they argue that it may not be possible to pinpoint the source of attained L2 knowledge of movement constraints, whether nativelike or not.

Applications

As mentioned earlier, a language acquirer's knowledge of abstract syntactic constraints and operations is tacit, considered largely inaccessible to introspection. The mechanisms of language processing are similarly not available to conscious awareness. Unlike, say, a knowledgeable poker player or basketball coach, who can readily transmit the rules of these games to other would-be players, theoretical linguists find themselves in the position of trying to infer what the “rules” of language are by observing whether the sentences the rules generate are well-formed or not. The formal nature of theoretical constructs, their level of abstraction and technical complexity, might render it difficult or even pointless to attempt to directly translate them into pedagogically useful guidelines. Chomsky (1966/71, pp. 152–155, cited in Widdowson, 2003) for example, noted the following:

I am, frankly, rather skeptical about the significance, for the teaching of languages, of such insights and understanding as have been attained in linguistics and psychology. ... It is possible—even likely—that principles of psychology and linguistics, and research in these disciplines, may supply insights useful to the language teacher. But these must be demonstrated, and cannot be presumed. ...

But let us concentrate for the moment on the possibility of morphosyntactic research supplying insights that might be useful to the language teacher, as Chomsky mentions. Widdowson (2003, pp. 11–12) points out that theoretical linguists (rightly) develop their own specialist discourses to suit their own disciplinary perspectives on language, as do language teachers, and that insights from linguistic theory cannot simply be supplied or “retailed” from one discourse to the other. Rather, he argues, it is up to applied linguists to act as mediating agents in both directions: to make linguistic insights intelligible to language teachers, as well as to perceive and (re-)formulate the learning or teaching problems such insights could effectively address.

In considering the applicability of SLA morphosyntactic research to language instruction, two broad candidate areas come to mind. The first is obvious: The impact of L1 knowledge (and processing routines; see Carroll, 2001; Hopp, 2010) in acquiring a second language cannot be denied. Ringbom and Jarvis (2009) describe the notion of transfer as “an umbrella term” for a learner's reliance on perceiving L1–L2 similarities between individual items and also the functional equivalences between the two underlying grammatical systems. The fewer the similarities, as in the case of less-closely-related languages, then the more difficult it will be to establish “how different L2 units correspond to L1 units and how they relate to the underlying concepts” (pp. 112–113). (The Feature-Reassembly approach is just one way of more formally articulating this observation in terms of the distribution of formal features among lexical items in each language.) The implication for language teaching, Ringbom and Jarvis suggest, is that teachers should focus on similarities between the L1 and L2: “In general terms, a good strategy would be to make use of, and even overuse, actual similarities at early stages of learning” (p. 114). Implicit in this proposal, however, is the assumption that a teacher will be explicitly, metalinguistically aware of such similarities (and their limits). Therefore, a teacher who has been exposed to some training in morphosyntactic comparative research, particularly comparison of the L1(s) and L2(s) in question, will be in a better position to devise ways (in the mediating sense of Widdowson, cited above) of incorporating its constructs and findings into the classroom.

The second area of applicability to teaching—once teachers have become aware of the differing distributions of formal features among morpholexical items in the L1 and L2—is attention to the contextual conditioning environments for expressing those features. It is not enough to know how to spell out a particular feature or grammatical construction (although of course one should know that); one must also learn exactly when and under what conditions it is correct to do so. We asked earlier, for example: What constitutes an obligatory context? For features whose expression is considered optional (such as plural-marking in Chinese discussed earlier) when is it syntactically, discursively or pragmatically appropriate to express them? Such optionality poses a thorny and persistent learning problem for language students (see, e.g., Sorace, 2003).

Future directions: “The end of syntax”?

To conclude, we briefly consider a few key issues that seem likely to shape the direction of future research in formal linguistic approaches to the study of the L2 acquisition of syntax and morpho-syntax. The first issue is whether acquisition researchers can continue to generate interesting testable hypotheses for language acquisition based on syntactic theory, especially Minimalist syntactic theory.

As R. Hawkins (2008, p. 445) points out, some of the properties that had been the basis for hypotheses about the availability of UG in SLA disappear under Minimalist assumptions. He cites Chomsky's (2001) suggestion that verb-raising, a formerly-parameterized core grammatical option that many generative SLA researchers have spent years intensively studying (see, e.g., Ayoun, 2003; R. Hawkins, 2001b; White, 2003 for discussion and summary overviews), is no longer a property of core or “narrow” syntax, but rather a consequence of linearization procedures at the interface with phonology (as are virtually all word-order phenomena now). If that is so, Hawkins writes, then L2 research on the acquisition of differences in verb-raising “would shed no light on the availability of innately determined features and computations in this domain” (p. 445).

Marantz (1995) refers to this ongoing relegation of formerly syntactic phenomena to the interfaces with phonology and semantics/pragmatics as “the end of syntax”:

The syntactic engine itself—the autonomous principles of composition and manipulation Chomsky now labels “the computational system”– has begun to fade into the background. ... A vision of the end of syntax—the end of the sub-field of linguistics that takes the computational system, between the interfaces, as its primary object of study—this vision encompasses the completion rather than the disappearance of syntax. (pp. 380–381)

As Marantz points out, however, this shift has the positive consequence of forcing syntacticians to “renew their interface credentials” by paying serious attention to work in phonology and semantics (p. 381; see also Jackendoff, 2002). The same is true, of course, for the study of language acquisition, including L2 acquisition. If the Minimalist vision of syntax is too general and abstract to allow us to generate testable predictions for SLA grammatical research, then such predictions will have to come from our developing understanding of the interaction of syntactic computation with other components of language knowledge. (See White, 2009 for an overview of recent L2 research which addresses linguistic interfaces.)

Another question is the extent to which special and general nativist concerns will continue to converge, and the limits of each approach. As J. Hawkins (2004, p. 273) observes, regardless of whether UG constructs such as subjacency constraints fall by the wayside as possible grounds for innateness claims in formal linguistics (a conclusion he persuasively argues for), there nonetheless remains a poverty-of-the-stimulus problem in language acquisition that must be addressed, “since one does have to explain how the child learns the limits on the set of possible sentences that go beyond the positive data to which he or she has been exposed.” We asked earlier: What can replace or recapture the original highly restrictive role of parameters in earlier UG theory? After all, a major motivation for positing parameters was to account not only for observed recurring cross-linguistic tendencies, but also for the observed rapid, uniformly successful acquisition of language by young children.

J. Hawkins’ own general-nativist solution (like that of O'Grady, 1996, 2008) is that language learners will comprehend input and construct grammars in accordance with innate processing and learning mechanisms, and that hierarchies of processing ease vs. complexity may structure initial hypotheses about the target grammar. Extensions beyond these initial hypotheses will need to be justified by the data of experience, just as we have posited for parameters. Because Chomsky's own current (2005, 2007) agenda for Minimalist syntax encompasses pursuing this latter possibility to account for language acquisition, we can anticipate that a consideration of proposed processing constraints and hierarchies such as those proposed by Hawkins will become increasingly important to special nativists as well as to general nativists in future SLA research. More specifically, Hawkins suggests that it will be important to find out whether factors thought to facilitate L2 acquisition, such as frequency effects and L1–L2 similarities, also operate within the ease-of-processing hierarchies and constraints that are hypothesized to account for crosslinguistic variation and native language acquisition (p. 275).

A final, related question we might ask is whether the P&P/Minimalist approach offers the best analytical tools for the job to those of us who work on formal linguistic approaches to grammatical acquisition. The answer, of course, depends on precisely what we are interested in studying, but future research at the “interfaces” with morphosyntax will require increasing familiarity with additional frameworks that are better suited for analyzing the type of data that interact with the syntactic computational component. The (optimality-theoretic-based) work by Goad and White (2004, 2006, 2008) on phonological analyses of prosodic factors impinging on morphological production, discussed earlier in this chapter, offers a striking case in point. For the acquisition of morphosyntax in particular, Carroll (2009, p. 252) argues that categorial and phrase structure grammatical frameworks offer a far richer theory of features and categories than Minimalism, and suggests that the field of SLA would benefit from a broader, “less parochial” perspective on syntactic theoretical frameworks than it has held over the past two decades.

Notes

* I am grateful to Lydia White and the editors of this volume for comments on an earlier draft of this chapter.

1 For a useful historical summary of refinements to conditions on wh-movement and their applicability to SLA, see Belikova and White (2009).

2 See O'Grady (1999) for a discussion of nativism and points of consensus as well as differences between general and special nativism.

3 This principle was originally proposed as the Extended Projection Principle in Chomsky (1981) and has undergone considerable revision over the evolution of P&P theory. The requirement that all clauses have subjects has more recently been recast as the Subject Criterion (Rizzi, 2006).

4 From these (mainly grouped, cross-sectional) L2 studies of morpheme suppliance in obligatory contexts, a developmental sequence or “natural order” of morpheme acquisition was extrapolated that cut across the various L1 backgrounds of the study participants, thus apparently minimizing the role of L1 influence. See various comprehensive introductory SLA course texts (e.g., R. Ellis, 2008; Gass and Selinker, 2008; Larsen-Freeman and Long, 1991) for morpheme-order study references and an overview.

5 A mature grammatical representation includes knowledge of syntactic phrase structure in which open-class, lexical-headed constituents such as verb phrases (VPs) and noun phrases (NPs) are grammatically contextualized, or extended, by hierarchically nesting them within functional-category-headed phrases such as “Complementizer phrases” (CP), “Infl(ectional)” phrases (IP, later subdivided into Tense and Agreement (TP/AgrP) as well as other functional subcategories), “Determiner phrases” (DP), and “Number phrases” (NumP) that encode formal features related to clause type, tense and agreement, definiteness, and plurality, respectively. The derived syntactic structure could be modeled something like that shown in (i), where “Spec(ifier)” represents a type of subject position:

(i) [CP Spec [C] [IP Spec [I] [VP Spec [V] [DP [D] [NumP [Num] [NP]]]]]] The overall CP>IP >VP hierarchy for clauses shown in (i) is broadly accepted as universal among P&P researchers, although the many (possibly language-specific) subcategories associated with these more general categories are subject to considerable debate. (Haegeman, 2006 provides an accessible introductory overview.)

6 There is some question in the syntactic literature regarding the “true” plural status of men suffixation in Chinese; see Li (1999) for arguments in support of the “plural marker” view. See Lardiere (2009a) for additional discussion.

7 Of course, English has phonetically conditioned allomorphy, as well as irregular plural-marking on certain nouns, which is why it is necessary to posit an underlying abstract morphosyntactic feature [+plural] that may be spelled out differently for different lexical items depending on particular language-specific conditioning factors (such as particular lexical roots, e.g., foot, ox, mouse, woman, etc.).

8 Technically, these terms are not interchangeable, as noted as far back as Chomsky (1965), although in actual practice they often are. Linguists have mostly assumed that grammatical knowledge is categorical— sentences are either grammatical or ungrammatical—and that the continuous spectrum of acceptability is caused by extra-grammatical factors (plausibility, working memory limitations, etc.) (Sprouse, 2007, p. 118).

9 However, see Nicolis (2008) for one apparently exceptionless implicational correlation between referential and expletive null subjects in null-subject languages, and an explanation for the correlation.

References

Anderson, B. (2008). Forms of evidence and grammatical development in the acquisition of adjective position in L2 French. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30, 1–29.

Ayoun, D. (2003). Parameter-setting theory in first and second language acquisition. New York: Continuum.

Belikova, A. and White, L. (2009). Evidence for the fundamental difference hypothesis or not? Island constraints revisited. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 31, 199–223.

Belletti, A. and Leonini, C. (2004). Subject inversion in L2 Italian. In S. Foster-Cohen, M. Sharwood Smith, A. Sorace and M. Ota (Eds.), EuroSLA Yearbook 2004 (pp. 95–118). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Biberauer, T. (2008). Introduction. In T. Biberauer (Ed.), The limits of syntactic variation (pp. 1–72). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Birdsong, D. (1989). Metalinguistic performance and interlanguage competence. New York: Springer.

Bley-Vroman, R. (1989). What is the logical problem of foreign language learning? In S. M. Gass and J. Schachter (Eds.), Linguistic perspectives on second language acquisition (pp. 41–68). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Bley-Vroman, R. (2009). The evolving context of the fundamental difference hypothesis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 31, 175–198.

Bley-Vroman, R., Felix, S., and Ioup, G. (1988). The accessibility of universal grammar in adult language learning. Second Language Research, 4, 1–32.

Brown, R. (1973). A first language: The early stages. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Carroll, S. E. (2001). Input and evidence: The raw material of second language acquisition. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Carroll, S. E. (2009). Re-assembling formal features in second language acquisition: Beyond minimalism. Second Language Research, 25, 245–253.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1966/71). In J. P. B. Allen and P. Van Buren (Eds.), Chomsky: Selected readings. New York: Oxford University Press.

Chomsky, N. (1981). Lectures on government and binding. Dordrecht: Foris.

Chomsky, N. (1986a). Knowledge of language. New York: Praeger.

Chomsky, N. (1986b). Barriers. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995a). The minimalist program. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (1995b). Bare phrase structure. In G. Webelhuth (Ed.), Government and binding theory and the minimalist program (pp. 385–439). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Chomsky, N. (2001). Derivation by phase. In M. Kenstowicz (Ed.), Ken Hale: A life in language (pp. 1–52). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, N. (2005). Three factors in language design. Linguistic Inquiry, 36, 1–22.

Chomsky, N. (2007). Approaching UG from below. In U. Sauerland and H. -M. Gärtner (Eds.), Interfaces + recursion = language? (pp. 1–29). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Clahsen, H. and Muysken, P. (1986). The availability of universal grammar to adult and child learners: A study of the acquisition of German word order. Second Language Research, 2, 93–119.

Dekydtspotter, L. (2001). The universal parser and interlanguage: Domain-specific mental organization in the comprehension of combien interrogatives in English-French interlanguage. Second Language Research, 17, 91–143.

Dekydtspotter, L. and Sprouse, R. A. (2001). Mental design and (second) language epistemology: Adjectival restrictions of wh-quantifiers and tense in English-French interlanguage. Second Language Research, 17, 1–35.

Eckman, F. (1996). On evaluating arguments for special nativism in second language acquisition theory. Second Language Research, 12, 398–419.

Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Eubank, L. (1996). Negation in early German-English interlanguage: More valueless features in the L2-initial state. Second Language Research, 12, 73–106.

Felix, S. (1985). More evidence on competing cognitive systems. Second Language Research, 1, 47–72.

Furkóné Banka, I. (2006). Resetting the null subject parameter by Hungarian learners of English. In M. Nikolov and J. Horváth (Eds.), UPRT 2006: Empirical studies in English applied linguistics (pp. 179–195). Pécs: Lingua Franca Csoport.

Gass, S. M. (2001). Sentence matching: A re-examination. Second Language Research, 17, 421–441.

Gass, S. M. and Selinker, L. (2008). Second language acquisition: An introductory course (3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Gavruseva, L. and Lardiere, D. (1996). The emergence of extended phrase structure in child L2 acquisition. In A. Stringfellow, D. Cahana-Amitay, E. Hughes, and A. Zukowski (Eds.), BUCLD 20 Proceedings (pp. 225–236). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Goad, H. and White, L. (2004). Ultimate attainment of L2 inflection: Effects of L1 prosodic structure. In S. Foster-Cohen, M. Sharwood Smith, A. Sorace, and M. Ota (Eds.), EuroSLA Yearbook (Vol. 4, pp. 119–145). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Goad, H. and White, L. (2006). Ultimate attainment in interlanguage grammars: A prosodic approach. Second Language Research, 22, 243–268.

Goad, H. and White, L. (2008). Prosodic structure and the representation of L2 functional morphology: A nativist approach. Lingua, 118, 577–594.

Greenberg, J. H. (1963). Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements. In J. H. Greenberg (Ed.), Universals of language (pp. 73–113). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Gregg, K. R. (1989). Second language acquisition theory: The case for a generative perspective. In S. Gass and J. Schachter (Eds.), Linguistic perspectives on second language acquisition (pp. 15–40). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gregg, K. R. (1996). The logical and developmental problems of second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie and T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 49–81). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Haegeman, L. (2006). Thinking syntactically: A guide to argumentation and analysis. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hawkins, J. A. (2004). Efficiency and complexity in grammars. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hawkins, R. (2001a). The theoretical significance of Universal Grammar in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 17, 345–367.

Hawkins, R. (2001b). Second language syntax: A generative introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Hawkins, R. (2003). “Representational deficit” theories of adult SLA: Evidence, counterevidence and implications. Plenary paper presented at EuroSLA, Edinburgh, September 2003.

Hawkins, R. (2008). Current emergentist and nativist perspectives on second language acquisition. Foreword to the special issue of Lingua, 118, 445–446.

Hawkins, R. and Chan, C. Y. -H. (1997). The partial availability of universal grammar in second language acquisition: The “failed functional features hypothesis”. Second Language Research, 13, 187–226.

Hawkins, R. and Hattori, H. (2006). Interpretation of English multiple wh-questions by Japanese speakers: A missing uninterpretable feature account. Second Language Research, 22, 269–301.

Hawkins, R. and Liszka, S. (2003). Locating the source of defective past tense marking in advanced L2 speakers. In R. van Hout, A. Hulk, F. Kuiken, and R. Towell (Eds.), The lexicon-syntax interface in second language acquisition (pp. 21–44). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Hopp, H. (2010) Ultimate attainment in L2 inflection: Performance similarities between non-native and native speakers. Lingua, 120, 901–931.

Jackendoff, R. (2002). Foundations of language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jiang, N. (2004). Morphological insensitivity in second language processing. Applied Psycholinguistics, 25, 603–634.

Jiang, N. (2007). Selective integration of linguistic knowledge in adult second language learning. Language Learning, 57, 1–33.

Johnson, J. and Newport, E. (1991). Critical period effects on universal properties of language: The status of subjacency in the acquisition of a second language. Cognition, 39, 215–258.

Kanno, K. (1998). The stability of UG principles in second language acquisition. Linguistics, 36, 1125–1146.

Kayne, R. S. (2005). Some notes on comparative syntax, with special reference to English and French. In G. Cinque and R. S. Kayne (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of comparative syntax (pp. 3–69). New York: Oxford University Press.

Lardiere, D. (1998). Case and tense in the “fossilized” steady state. Second Language Research, 14, 1–26.

Lardiere, D. (2000). Mapping features to forms in second language acquisition. In J. Archibald (Ed.), Second language acquisition and linguistic theory (pp. 102–129). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Lardiere, D. (2007). Ultimate attainment in second language acquisition: A case study. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lardiere, D. (2008). Feature assembly in second language acquisition. In J. M. Liceras, H. Zobl, and H. Goodluck (Eds.), The role of formal features in second language acquisition (pp. 106–140). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Lardiere, D. (2009a). Some thoughts on the contrastive analysis of features in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 25, 173–227.

Lardiere, D. (2009b). Further thoughts on parameters and features in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 25, 409–422.

Larsen-Freeman, D. and Long, M. H. (1991). An introduction to second language acquisition research. Essex, UK: Longman.

Li, Y. -H. A. (1999). Plurality in a classifier language. Journal of East Asian Linguistics, 8, 75–99.

Marantz, A. (1995). The minimalist program. In G. Webelhuth (Ed.), Government and binding theory and the minimalist program (pp. 351–382). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Martohardjono, G. (1993). Wh-movement in the acquisition of a second language: A cross-linguistic study of three languages with and without overt movement. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. Cornell University.

Meisel, J. M. (1997). The acquisition of the syntax of negation in French and German: Contrasting first and second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 13, 227–263.

Newmeyer, F. J. (1998). Language form and language function. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nicolis, M. (2008). The null subject parameter and correlating properties: The case of creole languages. In T. Biberauer (Ed.), The limits of syntactic variation (pp. 271–294). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

O'Grady, W. (1999). Toward a new nativism. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 21, 621–633.

O'Grady, W. (1996). Language acquisition without Universal Grammar: A general nativist proposal for L2 learning. Second Language Research, 12, 374–397.

O'Grady, W. (2008). Innateness, universal grammar, and emergentism. Lingua, 118, 620–631.

Phinney, M. (1987). The pro-drop parameter in second language acquisition. In T. Roeper and E. Williams (Eds.), Parameter setting (pp. 221–238). Dordrecht: Reidel.

Pérez-Leroux, A. T. and Glass, W. (1999). OPC effects in the L2 acquisition of Spanish. In A. T. PérezLeroux and W. Glass (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on the acquisition of Spanish, vol. 1: Developing grammars (pp. 149–165). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Ringbom, H. and Jarvis, S. (2009). The importance of cross-linguistic similarity in foreign language learning. In M. H. Long and C. J. Doughty (Eds.), The handbook of language teaching (pp. 106–118). Chichester, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

Rizzi, L. (1982). Issues in Italian syntax. Dordrecht: Foris.

Rizzi, L. (1986). Null objects in Italian and the theory of pro. Linguistic Inquiry, 17, 501–557.

Rizzi, L. (2006). On the form of chains: Criterial positions and ECP effects. In L. L. -S. Cheng and N. Corver (Eds.), Wh-movement: Moving on (pp. 97–133). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Saito, M. and Fukui, N. (1998). Order in phrase structure and movement. Linguistic Inquiry, 29, 439–474.

Sauter, K. (2002). Transfer and access to universal grammar in second language acquisition. Groningen Dissertations in Linguistics 41. University of Groningen.

Schachter, J. (1989). Testing a proposed universal. In S. M. Gass and J. Schachter (Eds.), Linguistic perspectives on second language acquisition (pp. 73–88). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Schachter, J. (1990). On the issue of completeness in second language acquisition. Second Language Research, 6, 93–124.

Schwartz, B. D. and Sprouse, R. A. (1996). L2 cognitive states and the Full Transfer/Full Access model. Second Language Research, 12, 40–72.

Schwartz, B. D. and Sprouse, R. A. (2000). When syntactic theories evolve: Consequences for L2 acquisition research. In J. Archibald (Ed.), Second language acquisition and linguistic theory (pp. 156–186). Oxford: Blackwell.

Schütze, C. (1996). The empirical base of linguistics: Grammaticality judgments and linguistic methodology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Snyder, W. (2000). An experimental investigation of syntactic satiation effects. Linguistic Inquiry, 31, 575–582.

Sorace, A. (1996). The use of acceptability judgments in second language acquisition research. In W. C. Ritchie and T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 375–409). San Diego: Academic Press.

Sorace, A. (2003). Near-nativeness. In C. J. Doughty and M. H. Long (Eds.), The handbook of second language acquisition (pp.–130–151). Oxford: Blackwell.

Sprouse, J. (2007). Continuous acceptability, categorical grammaticality, and experimental syntax. Biolinguistics, 1, 118–129.