22

Speaking and writing tasks and

their effects on second

language performance

Folkert Kuiken and Ineke Vedder

Historical discussion

It is hard to answer the question when the human race started speaking: was it 50,000, 150,000 or 250,000 years ago? And did humanoids start speaking immediately after they were physically able to do so? It is equally hard to tell when we began to write. Was it around 3000 BC judging by the Mesopotamian tablets which date from around that time? Or was it as early as 5000 or 8000 BC if we also include “forerunners” of writing that have been found on small clay objects at sites from Palestine to eastern Iran (Daniels and Bright, 1996)? How difficult these questions may be to answer, what is not contested is that speaking is primary and writing is secondary. This is still the case in modern society: children start to speak first and only later do they learn to write. But writing has become very important nowadays. A human being who cannot write will not be able to participate fully in daily life. And there are situations and contexts in which more importance is attached to the written than to the spoken word.

In second language learning oral and written tasks often go hand in hand. Although it is possible to learn a second language (L2) just by listening and responding orally to the input, within the context of instructed L2 learning most learners will use books or other written documents in order to acquire the target language. So from the very beginning of L2 learning the majority of learners will be submitted to both oral and written language tasks. Recently a lot of research has been done on various factors influencing task performance in a L2 (Ellis, 2003; Robinson, 1995, 2007; Skehan, 1998; among others). These factors include the type of task, the inherent cognitive complexity of the task, the conditions under which the task has to be performed (e.g., the number of participants involved) and the nature of the task (e.g., monologic or dialogic, open or closed). The mode (oral versus written) in which the task has to be completed is another factor that has to be taken into consideration, but surprisingly enough mode has attracted little attention in the L2 research agenda. It is precisely for this reason that in this chapter the focus is on the role of mode in second language acquisition (SLA).

Although their have been many studies which have looked at the effect of task type on linguistic performance, the majority of studies which have investigated the influence of particular task characteristics have concentrated on oral performance (Gilabert et al., 2009; Yuan and Ellis, 2003). Prabhu (1980, 1984, 1987) was one of the first to emphasize the effect of oral information gap tasks. These are tasks in which the participants do not have the same items of information so that they are forced to communicate with each other in order to solve the task. Information gap tasks were introduced to the SLA research context by Long (1980, 1985).

Long (1985) mentions six variables along which tasks can be varied, leading to more and better vs. less and weaker performance. These variables are: motivation, planning time, open versus closed tasks, convergent versus divergent tasks, one-way versus two-way tasks, and information gap tasks. Later research has confirmed many of Long's assumptions. For instance, with respect to planning, there is now ample evidence that almost any kind of planning helps the learners to perform better (Ellis, 2005, 2009). The results for complexity and accuracy are mixed, depending both on the type of planning and the mediating effect of various factors, including task design, implementation variables, and individual difference factors.

Other researchers who have explored the effect of task characteristics on oral performance are Skehan, Foster and Tavakoli (Foster and Skehan, 1996; Foster and Tavakoli, forthcoming; Skehan and Foster, 1997; Skehan, 2001, 2009; Tavakoli and Skehan, 2005). In these studies the outcomes of three types of tasks have been compared with each other: personal tasks (e.g., explain how to get to one's home to turn off an oven that has been left on), narrative tasks (e.g., making up a story from a series of pictures or a video fragment) and decision-making tasks (e.g., agree on the appropriate sentence for a series of crimes). In an overview study Skehan (2001, 2009) draws the following conclusions: (1) tasks requiring information manipulation lead to higher complexity; (2) interactive tasks favor accuracy and complexity; (3) tasks containing clear structure benefit accuracy and fluency; (4) tasks based on concrete or familiar information also advantage accuracy and fluency. There are, however, differences between the kind of tasks and even within a task: the picture-based narrative for instance yields other results than the video-based narrative. Task design, in other words, can influence the level of complexity, accuracy, or fluency for a particular task.

Whereas numerous studies on the relationship between task characteristics and linguistic output concern oral tasks, not many studies have examined the effects of task type and task complexity on the written performance of L2 learners. There are, however, some exceptions (Kuiken and Vedder, 2007a, b, c; Kuiken et al., 2005; among others). Moreover, there are only a few studies in which the effect of mode on linguistic performance in L2 or L1 has been established and a comparison is made between oral and written task performance (Grabowski, 2005, 2007; Granfeldt, 2007; among others). We have to keep in mind that in these studies, which will be discussed further on, the relationship between the influence of mode and particular task characteristics has often not been systematically explored. Moreover, as will be shown, the results that have been established so far are often contradictory.

Core issues

An important issue regarding the influence of speaking and writing tasks on L2 performance concerns the differences that exist between L2 speaking and writing. A major difference is to be found in the nature of the linguistic knowledge accessed by the learner and the underlying processes required for oral and written production (see the contributions of Pickering on speech production and of Polio on writing, Chapter 19, in this volume). While oral production is generally considered to give evidence of the learner's implicit knowledge, written production seems to allow for the use of explicit knowledge (Towell et al., 1996). Also the underlying language production processes related to speaking and writing differ from each other. As pointed out in several studies, a prerequisite for linguistic and thematic coherence in oral and written text production is to remember what has already been said or written. Compared to speaking, where the information which has already been produced must be maintained exclusively in memory, in writing the already written text can be re-read. Besides that, writing is often five to eight times slower than speaking, since more time is needed for the verbalization of content (Fayol, 1997). As a consequence, cognitive resources can be used for a longer period of time, from which information retrieval from long-term memory as well as planning should benefit. Moreover, while speech production requires continuous progress, language production in writing is self-determined: it is possible for the writer to stop the grapho-motoric process and to concentrate only on retrieval or on planning processes. The cognitive load of writing compared to speaking is therefore lower (Grabowski, 2007, pp. 168–170; Granfeldt, 2007).

In a study on the relationship between oral and written production and memory recall in L1, Grabowski (2005, 2007) investigated the question of how the diverse sub-processes of oral and written language production are related to memory span and whether they offer equivalent possibilities for learners to express their cognitive achievements. In a study, conducted among two groups of university students and primary schoolchildren in Germany, Grabowski found that for university students there was no mode effect on recall performance from working memory, whereas for schoolchildren a significant effect was observed, in favor of the oral mode. In a follow-up study in which the differential effects of oral and written task production in relation to recall from both long-term memory and working memory were examined, a significant difference between the two modes was detected. For adult learners, a robust and stable superiority effect of writing was reported on recall from long-term memory, in so far as the written mode seemed to reflect the underlying knowledge of the students better than the oral mode did. No differences between the oral and written mode, however, could be established with respect to recall performance from working memory (Grabowski, 2007).

Remarkably enough the distinction between oral tasks and written tasks and their effects on language performance has not often been an object of research. This may have to do with the fact that the majority of tasks (personal, narrative, problem solving, decision making, information gap, map tasks) can be performed in both the oral and written mode. This also holds for the variables mentioned by Long (1985): both oral and written tasks can be manipulated with respect to the amount of planning time allowed, and to the degree in which a task is open or closed, convergent or divergent, monologic or dialogic. Some variables, however, inherently seem to be more related to either an oral or a written task. This is, for instance, the case with the planning that learners undertake while they are performing a task (within-talk planning). As speaking is faster than writing, learners can do a lot more within-talk planning during writing, compared to speaking. Another example concerns interaction. In an oral situation there is generally an interlocutor who is present most of the time waiting for some kind of immediate response: in a tête-à-tête, throughout a Skype session, or during a phone call. This is not the case when somebody writes a letter, an SMS- or an e-mail message: although there is always an addressee, the interlocutor is not expected to react right away; except perhaps during a chat session, but even then the addressee may decide to take time to react. In other words, there is not so much of what could be defined as a prototypical oral task or a unique writing task. Nevertheless, some tasks are used more often in an oral situation, while others lend themselves better to the written mode.

To summarize: despite the similarities that exist between some oral and written tasks, there are several differences between speaking and writing, which may possibly lead to a differential influence of mode on linguistic performance. In the following section we will discuss the types of data that are used in studies on the effects of mode, the way the data are collected and analyzed, and the measures used in this type of research.

Data and common elicitation measures

Looking at the relatively small number of studies that have investigated the effects of mode on linguistic performance, one is struck by the enormous variety in the kind of tasks that have been used in these studies, the participants involved, the way the data have been collected and the measures that have been used to analyze the data.

With respect to the focus of the study and the participants involved, most researchers have submitted tasks to adult L2 learners, but with a variety of source languages and target languages, cf., L1 Hungarian—L2 English (Kormos and Trebits, 2009), L1 Spanish—L2 English (MartínezFlor, 2006), L1 Swedish—L2 French (Granfeldt, 2007), L1 Dutch—L2 French (Bulté and Housen, 2009), L1 Dutch—L2 Italian (Kuiken and Vedder, 2009, forthcoming). Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009) studied the acquisition of L2 Italian by younger learners of various language backgrounds. The research focus of the studies differed from a single focus on lexical complexity (Bulté and Housen, 2009; Yu, 2009) or pragmatic competence (Martínez-Flor, 2006), to a broader scope regarding grammatical complexity and accuracy (Ferrari and Nuzzo, 2009), or even grammatical complexity, lexical complexity, and accuracy (Granfeldt, 2007; Kormos and Trebits, 2009; Kuiken and Vedder, 2009, forthcoming).

Given these differences in participants and research focus it is not surprising that there is also much variation in the way the data have been collected and analyzed. Oral retelling and written narrative tasks were used by Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009) and by Kormos and Trebits (2009). Yu (2009) adopted written compositions and interviews, whereas Martínez-Flor (2006) used phone messages and e-mails. The L2 learners in Kuiken and Vedder (2009, forthcoming) had to fulfill two argumentative tasks. Besides these different tasks, various languages measures, both general and more specific, were employed. With respect to grammatical complexity general and specific measures were used, based on utterance length, the proportion of subordinate clauses (subclause ratio), or the use of cohesive devices. Measures which have often been used for measuring the lexicon are D, establishing lexical diversity (Malvern and Richards, 1997, 2002; Malvern et al., 2004), type-token ratio measures, and lexical profile measures, classifying the vocabulary into frequency bands (Laufer and Nation, 1995, 1999). Accuracy was measured by counting the number of errors, error-free clauses, and first, second, and third degree errors focusing on the seriousness of the errors. Fluency was measured by counting the number of repetitions and paraphrases. Pragmatic competence was established by the occurrence of target language forms for making suggestions.

These different source and target languages, the variety in participants, data collection procedures, and languages measures, make it hard to compare the various studies with each other and to draw unambiguous conclusions. Nevertheless, we will try to do so in the next section.

Empirical verification

Recently several studies have investigated the effect of mode on second language performance (Bulté and Housen, 2009; Ferrari and Nuzzo, 2009; Granfeldt, 2007; Kormos and Trebits, 2009; Kuiken and Vedder, 2009, forthcoming; Martínez-Flor, 2006; Yu, 2009). With respect to the influence of the oral versus the written mode on linguistic performance the results of the experimental studies which have been found so far are contradictory.

Granfeldt (2007) conducted a study among Swedish university students in which the effect of mode in oral and written L2 French was explored. Data collection took place in two sessions. In the first session the participants had to produce two expository texts. Half of the subjects spoke before writing and half of them wrote before speaking. In the second session the same procedure was repeated with two narrative texts. Due to the fact that writing, compared to speaking, allows more possibilities for control, planning, and monitoring, it was expected that the written L2 production would be characterized by a higher degree of complexity and accuracy than the oral production. Spelling and pronunciation errors were not taken into account. Although lexical complexity in writing turned out to be significantly higher than in speaking, contrary to expectations this was not the case for grammatical complexity, established both by a subclause ratio measure and by the occurrences of “advanced” syntactic structures. Furthermore, there were more errors in writing than in speaking. Although no general effect of mode was found in the study, there was a tendency toward individual differences between the learners, due to mode. A possible explanation could be that learners have preferences for either the oral or the written mode, as suggested by Weissberg (2000), who found that learners have “modality preferences” when it comes to morphosyntactic constructions.

In a study by Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009), a comparison was made of the grammatical complexity and accuracy of the spoken and written production of young L2 learners from various L1 backgrounds and L1 speakers of Italian, in an oral retelling task and a written narrative. Grammatical complexity was measured both by general measures, for example, number of words per clause, number of dependent clauses per AS-unit or T-unit (i.e., the dominant clause and its dependent clauses in respectively spoken and written discourse), and by specific measures (type of dependent clauses and the use of cohesive devices). The native speakers who tended to be more complex in the written mode than in the oral mode, produced longer clauses and more complex T-units. For the L2 learners there were fewer differences in the degree of syntactic subordination between the two modes, in spite of a slight superiority effect of the written mode. While native speakers seemed to use a wider variety of dependent clauses in the written narrative, there turned out to be no differences between the two modes for the non-native speakers. Both native and non-native speakers seemed to employ a wider range of connectors and textual anaphors in the written mode. With respect to accuracy, in line with the findings of Granfeldt (2007), L2 learners, unlike L1 learners, seemed to be more accurate in oral production. What these differences between native and non-native speakers seem to imply is that the superiority of either the oral or the written mode may also be constrained by the level of linguistic competence.

In the studies by Yu (2009) and Bulté and Housen (2009) the focus is on the development of lexical competence in L2. With respect to lexical complexity, there are a number of differences between oral and written task performance. Compared to written production, oral production is generally characterized by a high number of disfluency markers, repetitions, and paraphrases, a small range of clause connectors, lower lexical diversity and the use of more high-frequent words. Yu (2009), in a study on the lexical complexity of spoken and written discourse produced by L2 learners of English from various language backgrounds, compared lexical diversity in written compositions and interviews. The main finding of the study was that the lexical diversity of the writing and speaking performance of the L2 learners, as established by D (Malvern and Richards, 1997, 2002; Malvern et al., 2004), was not only significantly positively related, but also approximately at the same level. On the basis of these results Yu suggests that lexical diversity does not seem to be affected by task types (written compositions vs. spontaneaous interviews) or other task type characteristics such as pre-task planning and time pressure.

Bulté and Housen (2009) examined the development of lexical competence, in L2 speaking and writing in L2 French by native speakers of Dutch in Belgium. Lexical competence was measured by different quantitative and qualitative measures often employed for establishing lexical diversity (type-token ratio measures, D, Guiraud Index of Lexical Richness, Uber, lexical profile measures). The main result of the study was that although most of the measures indicated a significant increase in proficiency, both in the oral and the written task, this development did not seem to run in parallel for spoken and written tasks. Contrary to Yu (2009), but similar to Granfeldt (2007), the scores on the written tasks were generally higher than the scores on the oral tasks, for all the measures employed, except for the lexical profile measures.

Kormos and Trebits (2009) compared the grammatical and lexical complexity, accuracy and the use of cohesive devices in the written and spoken production of a group of Hungarian L2 learners of English in a Hungarian bilingual secondary school, in two oral and two written narrative tasks (a cartoon description and a story narration). Both general and specific linguistic measures were used. Grammatical complexity and text cohesion were measured by specific measures (occurences and types of coordinate and subordinate clauses; use of grammatical and lexical cohesive devices). Lexical complexity, operationalized as lexical diversity and lexical sophistication, was measured by D and by lexical profile measures (Laufer and Nation, 1995, 1999). Accuracy was established by means of the occurrence of error-free past-tense verbs, relative clauses, and error free clauses. Similar to the findings of Bulté and Housen (2009) and Granfeldt (2007), a superiority effect of the written mode was found for both lexical diversity and lexical sophistication. Contrary to the results of Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009) and Granfeldt (2007), no differences between the oral and the written mode were found with respect to grammatical complexity, while accuracy seemed to be higher in the written mode. In the written mode also the number of lexical cohesive devices was higher, although with respect to grammatical cohesive devices no differences between the two modes could be established.

In a study on the development of pragmatic competence by Spanish learners of English, Martínez-Flor (2006) examined the production of target language forms that had been selected for expressing suggestions in oral and written production tasks (i.e., phone messages and emails) by intermediate university students of English, with Spanish as their L1. In the study a higher number of pragmalinguistic target forms (e.g., modifiers, modals) in appropriate contexts (i.e., equal or higher status situation) was produced by the learners in the written production task. This finding contrasts with previous studies concerning the oral and written production of speech acts in L2, in which a greater amount of target forms in the oral task was found (Houck and Gass, 1996).

Kuiken and Vedder (2009, forthcoming) investigated the influence of task complexity on grammatical and lexical complexity and accuracy, in relation to the mode in which the tasks were performed. To investigate these effects a study was set up in which two tasks which previously had been submitted to a group of learners of Italian L2 in the written mode, were presented to another group as speaking tasks. In these tasks task complexity was manipulated along two variables of the Multiple Resources Attentional Model (Robinson, 1995, 2007): the number of elements to be taken into account and the reasoning demands posed by the task. The participants in the oral mode were 44 learners of Italian as a second language, with Dutch as their mother tongue. Their performance was compared with that of another group of 91 Italian L2 learners who had performed the same tasks in the written mode. In the study, differences between the oral and written performance of the learners, in relation to the influence of task complexity, were found only with respect to grammatical complexity, as the number of dependent clauses per clause in the complex task turned out to be lower in the oral mode. No differences between the oral and the written mode were detected regarding the number of clauses per T-unit, or with respect to the lexical complexity and accuracy of the output.

The results that have been obtained so far by studies in which the influence of mode on L2 performace was investigated are summarized in Table 22.1. With respect to grammatical complexity Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009) and Kuiken and Vedder (2009, forthcoming) found a superiority effect of the written mode (more subordination), whereas Granfeldt (2007) and Kormos and Trebits (2009) did not observe a difference between the two modes. Concerning lexical complexity a similar picture emerges: a superiority effect of the written mode was established by Granfeldt (2007), Bulté and Housen (2009) and Kormos and Trebits (2009), while Yu (2009) and Kuiken and Vedder (2009, forthcoming) could not detect a difference between the oral and the written mode. The picture tends to become even more diversified if we include findings on accuracy: Kuiken and Vedder (forthcoming) did not find any differences between the two modes, whereas Granfeldt (2007) and Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009) found a superiority effect of the oral mode, contrary to Kormos and Trebits (2009) who observed a superiority effect of the written mode.

Table 22.1 Studies which have investigated language performance in the oral and written mode

Superiority of written mode |

Superiority of oral mode |

No effect of mode |

|

| Grammatical complexity | Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009) |

Granfeldt (2007) Kormos and Trebits (2009) |

|

Kuiken and Vedder (forthcoming) |

|||

| Lexical complexity | Granfeldt (2007) Bulté and Housen (2009) |

Yu (2009) Kuiken and Vedder (forthcoming) |

|

Kormos and Trebits (2009) |

|||

| Accuracy | Kormos and Trebits (2009) |

Granfeldt (2007) Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009) |

Kuiken and Vedder (forthcoming) |

All in all, this means that an unequivocal effect of mode with respect to grammatical complexity, lexical complexity and accuracy cannot yet be established. Regarding grammatical and lexical complexity some studies did not observe any effects of mode. Those studies that did find such an influence, observed a superiority effect of the written mode. As far as accuracy is concerned, the results that have emerged so far seem to point in all possible directions: no effect of mode, superiority of the oral mode, or superiority of the written mode.

Applications

In this section we will turn to the practice of language teaching and present some characteristic speaking and writing tasks. We will first discuss two information gap tasks, as examples of speaking tasks eliciting oral output. Then we will present a “typical” writing task, consisting in an argumentative letter to be sent to the editorial board of a newspaper. Next we will discuss a dictogloss task as an example of a task which includes both an oral and a written component. It will be shown how in a dictogloss task, both the oral and written mode may reinforce each other.

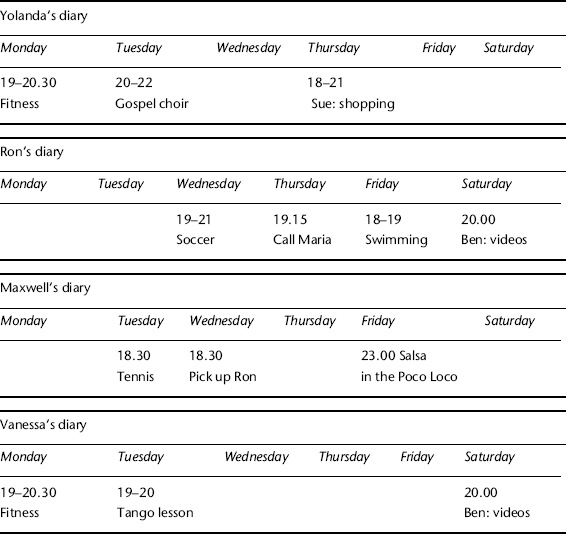

Information gap tasks. An information gap task is usally performed orally. Information gap tasks generally ask learners to find differences between (series of) pictures, to order sentences in stories, or to restore portions of incomplete maps and charts. As learners carry out these activities, they engage in functional, meaning-focused use of the target language, and gain acces to input for learning (Pica, et al., 2006). For a typical example of an information gap task see Box 22.1 (based on Ur, 1988, pp. 99–105).

The task presented in Box 22.1 is an example of a convergent task in which interaction leads to a specific goal or outcome, in this case an appointment between the four participants involved. In order to be able to reach this outcome, verbal exchange of information between the participants is required by the task. As Pica et al. (2006) note, such tasks are among the most productive for L2 acquisition: they set up conditions for participants to modify their interaction through negotiation of meaning. Moreover, as learners repeat and rephrase utterances (e.g., “Are your free on Monday? No, on Monday I cannot make it”) to make sure that their information is accurate and understood, information gap tasks also draw the attention of the learners to the linguistic forms that encode these utterances, in this example question formation and negation.

Making an appointment as presented in Box 22.1 is a task which mostly will be carried out orally, based on an authentic situation: the four participants involved in the task draw their agendas and discuss possible time slots to meet each other. The task, however, is not exclusively and necessarily an oral task. Although the appointment is made orally, the four learners have to consult the written information in their diaries to be able to arrange a meeting. And thanks to electronic diaries, nowadays it would even be possible for just one person (e.g., an office secretary) to perform the whole task on her/his own, without ever speaking a single word, provided that she/he has access to the electronic diaries of the participants. But, as in real life, this would make things much duller, as the buzz of making the appointment is already part of the fun of the whole event.

Box 22.1 Making an appointment

Source: (Based on Ur, 1988, pp. 99–105)

In an article on the multiple roles of information gap tasks and the contribution these tasks can make to research methodology, Pica et al. (2006) present another example of an information gap task. In this task a (written) review of a film is used as a starting point. After having read the original review individually, the learners are grouped into pairs, and each member of a pair receives a slightly modified version of the text. In this spot-the-difference task the learners are asked to discuss, sentence by sentence, which of the two versions is the correct one (e.g., “We see Andrew as a typical workaholic attorney” versus “We see Andrew as one typical workaholic attorney”). The next task is a jigsaw task, in which the sentences of the original review have been shuffled, and together each pair has to put the sentences in the correct order. Finally a grammar communication task has to be completed consisting of a fill-in-the blanks exercise in which the right word to fill in the blanks has to be chosen. Although a lot of written information has to be processed, the real processing occurs during the oral interaction phase, when learners have to work together to detect the differences in the information each of them has been provided with, and to decide which solution is correct and which is not. Besides the filling-in-the blanks activity, there is no writing involved in the task. Even if learners are provided with written textual input to carry out the task, the main focus is thus on the oral processing of particular grammatical structures.

Argumentative writing tasks. The following example of a writing task has been taken from a study by Kuiken et al. (2010), in which the relationship in L2 writing between linguistic complexity and communicative adequacy is investigated. The task submitted to the participants consists of an argumentative letter which has to be written to the editorial board of a newspaper. The learners have to convince the editorial board to select, out of three options, a particular topic for the leading article of the monthly supplement of the newspaper. In their letter the participants, who have to take into account a number of criteria, are asked to come up with at least three arguments. Since in this writing task learners are not allowed to interact with each other, they are left to their own devices while conceptualizing the letter and putting their ideas on paper (see Box 22.2).

The task presented in Box 22.2 can be considered semi-authentic, as it may be quite natural for an editorial board of a newspaper to invite its readers once in a month to have a say in the contents. However, instead of asking the readers to come up with a written report of their choice, it might also be possible to organize an oral panel discussion, during which readers express their opinion on what should be the leading article for the monthly supplement. Although the task presented in Box 22.2 can be considered a typical example of a writing task, it is not necessarily the case that this task can only be performed as a writing activity, similarly to the information gap task (e.g., making an appointment) which can be performed both as a speaking and a writing task.

Dictogloss. In a dictogloss task, described by Wajnryb (1990), L2 learners have to reconstruct both in the oral and in the written mode a short text read to them by the teacher at normal speed. This text, either a constructed text or an authentic one, is intended to provide practice in the use of particular linguistic forms or constructions (e.g., the use of passives). While the text is being read, learners first take notes; and then work together in small groups to reconstruct the initial text from their shared resources. After the reconstruction phase, the final version produced by each group is compared with the original text, and analyzed and commented on by the teacher. The dictogloss procedure allows the teacher to compare and to analyze both the oral output of the participants (i.e., the transcripts of the recordings of the interaction going on between the learners) and the written output (i.e., the text produced by the learners). As hypothesized in the literature, while learners interact with each other, as a result of this co-construction of L2 knowledge their language ability will improve, as far as their morpho-syntactic, lexical, and pragma-rhetorical skills are concerned (Swain and Lapkin, 2001; see also the chapter on interaction by Mackey, Abbuhl and Gass Chapter 1, in this volume).

Box 22.2 Writing an argumentative text

Every month your favorite newspaper invites its readers to have a say in what will be the leading article for the monthly supplement. This time the Editorial Board has come up with three suggestions: (1) global warming, (2) physical education, (3) animal experiments.

Out of these three suggestions one has to be selected. The selection is made by a Readers’ Committee. Every member of the committee has to write a report to the editors in which she/he states which article should be selected and why. On the basis of the arguments given by the committee members the Editorial Board will decide which article will be published on the front page. This month you have been invited to be a member of the Readers’ Committee. Read the brief descriptions of the suggestions for articles below. Determine which article should be on the front page and why. Write a report in which you give at least three arguments for your choice. Try to be as clear as possible and include the following points in your report:

- • which article should be selected;

- • what the importance of the article is;

- • which readers will be interested in the article;

- • why the Editorial Board should place this article on the front page of the monthly supplement.

You have 35 minutes available to write your text and you need to write at least 150 words (about 15 lines). The use of a dictionary is not allowed.

Suggestions for articles:

(1) Global warming: there is an ongoing political and public debate worldwide regarding what, if any, action should be taken to reduce global warming.

(2) Physical education: the government is launching a campaign in order to prevent people from becoming obese and to encourage them to move more.

(3) Animal experiments: it is estimated that 50 to 100 million animals worldwide are used annually and killed during or after experiments.

Source: (Kuiken et al., 2010)

This can be illustrated by means of an excerpt in which three Dutch L2 learners of English, Lovella, Fabe, and Hester, are reconstructing a text about a stolen painting, based on Willis (1991, p. 171) (cf., Kuiken and Vedder, 2002a, b, 2005). Box 22.3 contains the reconstructed text produced by the students. We will focus on one particular sentence of the reconstructed version: “At Liverpool airport the exchange took place.” Although the reconstructed version contains a couple of errors, the students have succeeded quite well in reproducing the global contents of the text (see Box 22.4).

As can be noted from the excerpt in Box 22.4 the students have considerable trouble in formulating the sentence “At Liverpool airport the exchange took place.” They first hesitate about the use of the preposition “in” versus “at”: do they have to say “in Liverpool airport” or “at Liverpool airport”? They quickly opt for “at,” as this “sounds more logical” to them. In spite of some doubts concerning the word “exchange,” they then decide that “exchange” is probably the correct solution “since it was an exchange.” But their main problem resides in the construction of the verbal phrase. Before finally deciding to write down “the

Box 22.3 The stolen painting: Reconstructed text

Two men tried to steal a painting who was owned by Mary Jones, aged 84 years old. She said that maybe an anchester showed the painting to the two men. She should have received the painting as a wedding present in 1941, but she didn't receive it untill 1945. Mr X (who's name can't be told for legal reasons) who was accused of stealing it, liked to sell the painting for a cheap price to get rid of it. At Liverpool airport the exchange took place. The buyer was flown in there with the money. At first, he was shown the painting in a banner, then he showed the money in a suitcase to Mr X. But the police had surrounded the airport and they arrested Mr X.

Box 22.4 Excerpt of the discussion between three students during the reconstruction phase1

Lovella: |

Okay, so it was “in Liverpool airport” or something like that. |

Fabe: |

Yes. |

Lovella: |

“At” or “at Liverpool airport” er ... |

Hester: |

“At” sounds more logical. |

Lovella: |

Yes, “at,” okay, but do we say then “at Liverpool airport er the exchange would find place” or something like that? |

Fabe: |

Yeah, “would taken” er ... |

Lovella: |

“Would ha ...” |

Fabe: |

“Would ...” |

Lovella: |

“Would taken,” no, “would take place.” |

Fabe: |

Yeah, is that okay? |

Lovella: |

Or “the agreement” or so, no “the exchange” for it was an exchange. |

Fabe: |

Yes, it was an exchange, yeah. |

Lovella: |

So “at Liverpool airport ... the exchange ... er would er, would ..., no, once more.” |

Fabe: |

Shit. |

Lovella: |

So it was in any case ... for in Dutch it is, so to say, at the airport of Liverpool ... |

Fabe: |

At the airport ... |

Lovella: |

The exchange would, will ..., so ..., “at Liverpool ... airport ... the exchange should have been ...” |

Fabe: |

“Taking place.” |

Lovella: |

Yes. |

Fabe: |

That is a lot of verbs at a row. |

Lovella: |

Yeah, so “at Liverpool airport the exchange would ... take place,” yes, it would take place there. |

Fabe: |

Yeah, “would ...” |

Lovella: |

“Would take place,” isn't it? |

Fabe: |

Yes. |

Note:

1 The discussion was held partly in Dutch, partly in English, but has been translated into English. Words pronounced originally in English have been put between quotation marks.

exchange took place,” as shown in the text in Box 22.3, several options are proposed and discussed: “would taken,” “would ha ...,” “would take place,” “would, will ...,” “should have been taking place” and again “would take place.” The discussion in the excerpt presented in Box 22.4 stops at this point. However, after having completed and re-read the reconstructed version of the text, “would take place” is cancelled once more and finally replaced by “took place.”

The excerpt in Box 22.4 illustrates the extensive deliberations going on between the participants before deciding to commit something to paper. It also shows how students are co-constructing sentences and how they hesitate between the use of various structures before a final decision is taken. One may wonder if learners would have used the correct verbal structures in the reconstructed text, if they had not been offered the opportunity to discuss these constructions together. Oral interaction may thus enhance the quality of a written text. This is precisely the aim of dictogloss: a task in which L2 learners have to collaborate, both in the oral and the written mode, in order to complete the task, and as a result the two modes will reinforce each other.

Future directions

As demonstrated by the research findings presented in the preceding sections, a contradictory picture emerges concerning the superiority of either the oral or the written mode with regard to grammatical complexity, lexical complexity, and accuracy. The fact that a straightforward conclusion with respect to the effect of mode cannot be drawn has several reasons. First of all, the number of studies that have investigated the effect of mode is rather small. Secondly, the tasks the participants in the studies were submitted to vary from simple descriptive tasks to more complex reasoning tasks. Thirdly, these studies differ from each other with respect to the kind of learners involved in the experiment, their source and target languages, and the performance measures which have been used. Fourthly, it is possible that learners may have particular preferences for either the oral or the written mode, as suggested by Weissberg (2000) and finally, the superiority of a particular mode may also be constrained by the level of L2 proficiency, as observed by both Granfeldt (2007) and Ferrari and Nuzzo (2009).

With regard to the distinction between oral and written tasks we have presented some examples of so-called “typical” speaking and writing tasks. We should, however, keep in mind, that there is not so much of what could be defined a prototypical oral task or a unique writing task, as a large number of tasks can be performed in both modes, as demonstrated by the dictogloss task. This allows teachers and researchers to compare the oral and written production of their learners and to detect possible differences in task outcomes, depending on whether the task has been carried out orally or in the written mode.

Our overview of studies that have investigated the role of mode in SLA shows that we are left with many questions of what is exactly the effect of speaking and writing tasks on L2 performance. We therefore conclude this chapter by suggesting three research questions which in our view are worth investigating in order to get a a better insight in the effect of mode on L2 performance. These questions are:

(1) How do task type and task complexity relate to the effect of mode?

(2) To which extent is the superiority of either the oral or the written mode constrained by the proficiency level of the learners?

(3) How can preferences of learners for either the oral or the written mode be explained?

References

Bulté, B. and Housen, A. (2009). The development of lexical proficiency in L2 speaking and writing tasks by Dutch-speaking learners of French in Brussels. Paper presented in the colloquium “Tasks across modalities”, Task Based Language Teaching Conference, Lancaster 2009.

Daniels, P. T. and Bright, W. (Eds.) (1996). The world's writing systems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (Ed.) (2005). Planning and task performance in a second language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Ellis, R. (2009). The differential effects of three types of task planning on the fluency, complexity and accuracy in L2 oral production. Applied Linguistics, 30(4), 474–509.

Fayol, M. (1997). Des idées au texte. Psychologie cognitive de la production verbale, orale et écrite. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

Ferrari, S. and Nuzzo, E. (2009) Meeting the challenge of diversity with TBLT: Connecting speaking and writing in mainstream classrooms. Paper presented in the colloquium “Tasks across modalities”, Task Based Language Teaching Conference, Lancaster 2009.

Foster, P. and Skehan, P. (1996). The influence of planning on performance in task-based learning. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 18(3), 299–324.

Foster, P. and Tavakoli, P. (forthcoming). The impact of narrative structure on native speaker task performance.

Gilabert, R., Barón, J., and Llanes, A. (2009). Manipulating cognitive complexity across task types and its impact on learners’ interaction during oral performance. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 47(3–4), 367–395.

Grabowski, J. (2005). Speaking, writing, and memory span performance: Replicating the Bourdin and Fayol results on cognitive load in German children and adults. In L. Allal and J. Dolz (Eds.), Proceedings Writing 2004. Geneva (CH): Adcom Productions (CD-ROM).

Grabowski, J. (2007). The writing superiority effect in the verbal recall of knowledge: Sources and determinants. In G. Rijlaarsdam (Series Ed.) and M. Torrance, L. van Waes, and D. Galbraith (Volume Eds.) Writing and cognition: Research and applications (Studies in Writing) (pp. 165–179). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Granfeldt, J. (2007). Speaking and writing in L2 French: Exploring effects on fluency, accuracy and complexity. In S. Van Daele, A. Housen, F. Kuiken, M. Pierrard, and I. Vedder (Eds.), Complexity, accuracy and fluency in second language use, learning and teaching (pp. 87–98). Brussels: KVAB.

Houck, N. and Gass, S. M. (1996). Non-native refusals: A methodological perspective. In S. Gass and J. Neu (Eds.), Speech acts across culture (pp. 45–64). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kormos, J. and Trebits, A. (2009). Task-related differences across modes of performance. Paper presented at the Task Based Language Teaching Conference, Lancaster 2009.

Kuiken, F., Mos, M., and Vedder, I. (2005). Cognitive task complexity and second language writing performance. In S. Foster-Cohen, M. P. García Mayo, and J. Cenoz (Eds.), Eurosla Yearbook (Vol. 5, pp. 195–222). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (2002a). Collaborative writing in L2: The effect of group interaction on text quality. In G. Rijlaarsdam, M. L. Barbier, and S. Ransdell (Eds.), New directions for research in L2 writing (pp. 168–187). Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (2002b). The effect of interaction in acquiring the grammar of a second language. International Journal of Educational Research, 37, 343–358.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (2005). Noticing and the role of interaction in promoting language learning. In A. Housen and M. Pierrard (Eds.), Investigations in instructed second language acquisition (pp. 353–381). Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (2007a). Cognitive task complexity and linguistic performance in French L2 writing. In M. P. García Mayo (Ed.), Investigating tasks in formal language learning (pp. 117–135). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (2007b). Task complexity and measures of linguistic performance in L2 writing. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 45(3), 261–284.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (2007c). Cognitive task complexity and written output in Italian and French as a foreign language. Journal of Second Language Writing, 17(1), 48–60.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (2009). Tasks across modalities: The influence of task complexity on linguistic performance in L2 writing and speaking. Paper presented in the colloquium “Tasks across modalities”, Task Based Language Teaching Conference, Lancaster 2009.

Kuiken, F. and Vedder, I. (forthcoming). Task complexity and linguistic performance in L2 writing and speaking: The effect of mode. In P. Robinson (Ed.), Second language task complexity: Researching the Cognition Hypothesis of language learning and performance (pp. 91–104). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Kuiken, F., Vedder, I., and Gilabert, R. (2010). Communicative adequacy and linguistic complexity in L2 writing. In I. Bartning, M. Martin, and I. Vedder (Eds.), Communicative proficiency and linguistic development: Intersections between SLA and language testing research. Eurosla Monograph Series:1, 81–100.

Laufer, B. and Nation, P. (1995). Vocabulary size and use: Lexical richness in L2 written production. Applied Linguistics, 16, 33–51.

Laufer, B. and Nation, P. (1999). A vocabulary-size test of controlled productive ability. Language Testing, 13, 151–172.

Long, M. H. (1980). Input, interaction and second language acquisition. Doctoral dissertation. UCLA. Dissertation Abstracts International, 41, 5082.

Long, M. H. (1985). Input and second language acquisition theory. In S. M. Gass and C. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acquisition (pp. 377–393). Rowley, MA: Newbury House.

Malvern, D. and Richards, B. (1997). A new measure of lexical diversity. In A. Byran and A. Wray (Eds.), Evaluating models of language (pp. 58–71). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Malvern, D. and Richards, B. (2002). Investigating accommodation in language proficiency interviews using a new measure of lexical diversity. Language Testing, 19, 85–104.

Malvern, D., Richards, B., Chipere, N., and Durán, P. (2004). Lexical diversity and language development: Quantification and assessment. Basingstoke, Englans: Palgrave Macmillan.

Martínez-Flor, A. (2006). Task effects on EFL learners productions of suggestions: A focus on elicited phone messages and emails. Miscelánae: A journal of English and American Studies, 33, 47–64.

Pica, T., Kang, H. -S., and Sauro, S. (2006). Information gap tasks: Their multiple roles and contributions to interaction research methodology. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(2), 301–338.

Prabhu, N. S. (1980). Reactions and predictions (Special issue). Bulletin 4(1). Bangalore: Regional Institute of English, South India.

Prabhu, N. S. (1984). Procedural syllabuses. In T. E. Read (Ed.), Trends in language syllabus design (pp. 272–280). Singapore: Singapore University Press/RELC.

Prabhu, N. S. (1987). Second language pedagogy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Robinson, P. (1995). Task complexity and second language narrative discourse. Language Learning, 45(1), 99–145.

Robinson, P. (2007). Task complexity, theory of mind, and intentional reasoning: Effects on L2 speech production, interaction, uptake and perceptions of task difficulty. International Review of Applied Linguistics, 43, 1–31.

Skehan, P. (1998). A cognitive approach to language learning. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Skehan, P. (2001). Tasks and language performance assessment. In M. Bygate, P. Skehan, and M. Swain (Eds.), Researching pedagogic tasks: Second language learning, teaching, and testing (pp. 167–185). London: Longman.

Skehan, P. (2009). Modelling second language performance: Integrating complexity, accuracy, fluency and lexis. Applied Linguistics, 30(4), 510–532.

Skehan, P. and Foster, P. (1997). Task type and processing conditions as influences on foreign language performance. Language Teaching Research, 1(3), 185–211.

Swain, M. and Lapkin, S. (2001). Focus on form through collaborative dialogue: Exploring task effects. In M. Bygate, P. Skehan, and M. Swain (Eds.), Researching pedagogic tasks. Second language learning, teaching and testing (pp. 99–118). Harlow: Pearson Education.

Tavakoli, P. and Skehan, P. (2005). Planning, task structure, and performance testing. In R. Ellis (Ed.), Strategic planning and task performance in a second language (pp. 230–273). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Towell, R., Hawkins, R., and Bazergui, N. (1996). The development of fluency in advanced learners of French. Applied Linguistics, 17(1), 84–119.

Ur, P. (1988). Grammar practice activities. A practical guide for teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wajnryb, R. (1990). Grammar dictation. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Weissberg, R. (2000). Developmental relationships in the acquisition of English writing vs speech. Learning and Instruction, 10, 37–53.

Willis, D. (1991). Collins Cobuild Student's Grammar. London: HarperCollins Publishers.

Yu, G. (2009). Lexical diversity in writing and speaking task performances. Applied Linguistics Advance Access. Published on June 4, 2009. doi:10.1093/applin/amp024.

Yuan, F. and Ellis, R. (2003). The effects of pre-task planning and on-line planning on fluency, complexity and accuracy in L2 monologic oral production. Applied Linguistics, 24(1), 1–27.