27

Age effects in second

language learning

Robert DeKeyser

Introduction

Age effects in first and second language learning are a well-known phenomenon. Any layperson is familiar with stories of immigrant families where, after a few years, the children speak like native speakers of the same age while the parents keep being recognized as non-natives for the rest of their lives. The popular press has also familiarized many with the concept of “feral children,” raised in circumstances of extreme neglect, and unable to become full-fledged speakers of any language after being rescued from their situation at an age beyond which first language learning (L1) is largely complete under normal circumstances (see, e.g., Benzaquén, 2006; Rymer, 1992). As is often the case, the media have promoted simplistic implications of these phenomena, such as a presumed impossibility of adults becoming highly skilled in a second language (L2) and the presumed ability of elementary school programs to instill a high level of L2 skill in all children, thus making it seem that age is the one and only determinant of success at language learning.

Historical discussion

In the last half-century, researchers have taken various positions on the role of age in second language development. In 1959, the neurologists Penfield and Roberts advocated early immersion in a second language because they thought that decreasing brain plasticity with increasing age made it much harder to learn a language later on. In 1967, the linguist Eric Lenneberg borrowed the term “critical period” from studies on animal behavior and applied it to language learning in humans, again using brain plasticity as an argument. Ever since then, few have doubted that there is a critical period for first language learning. What remains controversial, however, is whether the age effects commonly seen in second language learning also reflect a critical period; what is still completely unknown is exactly what aspects of brain maturation would be responsible for such a loss of plasticity. Lenneberg's (1967) assumption that increasing lateralization was to blame is no longer viable, as more recent research has shown that lateralization is complete by early infancy if not at birth (Hahn, 1987; Marzi, 1996).

In other respects, however, Lenneberg sounds surprisingly modern, and the seeds of much current debate can be found in this passage from his book:

[O]ur ability to learn foreign languages tends to confuse the picture. Most individuals of average intelligence are able to learn a second language after the beginning of their second decade, although the incidence of “language-learning-blocks” rapidly increases after puberty. Also automatic acquisition from mere exposure to a given language seems to disappear after this age, and foreign languages have to be taught and learned through a conscious and labored effort. Foreign accents cannot be overcome easily after puberty. However, a person can learn to communicate in a foreign language at the age of forty. This does not trouble our basic hypothesis on age limitations because we may assume that the cerebral organization for language learning as such has taken place during childhood, and since natural languages tend to resemble one another in many fundamental aspects (...), the matrix for language skill is present.

(1967, p. 176)

Lenneberg clearly realized that adults can learn a foreign language well, but that this does not contradict the critical period hypothesis because (a) these individuals, by definition, have the advantage of having learned a language already, which means that some of the most fundamental principles do not have to be learned at a later age, (b) being cognitively more mature, they are good at learning specific aspects of the L2 through mechanisms that adults or adolescents are good at (explicit learning), even though this means more effort, and (c) in spite of this cognitive maturity and this effort, the results tend to fall short of native-speaker standards, which is especially obvious in the area of pronunciation. Many studies of the last 20 years or so pick up on various threads present in this piece of text: Johnson and Newport's (1989) discussion of the maturation hypothesis vs. the exercise hypothesis, Mayberry's (1993) comparison of age effects on L1 and L2, BleyVroman's (1988, 2009) fundamental difference hypothesis, and DeKeyser's (2000), Ullman's (2001, 2005) and Paradis’ (2004, 2009) claim that aging implies a shift from implicit/procedural to explicit/declarative learning.

Lenneberg's (1967) and Penfield and Roberts’ (1959) work did not exactly provide the spark for much empirical research right away (even though it did provide the impulse for Foreign Language in the Elementary School practice from the 1960s onward). A few more or less isolated behavioral studies were published in the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, involving mostly global ratings of pronunciation and grammar, but the past two decades have seen a burgeoning of research in the area of age effects, both behavioral and neurological, with increasing conceptual and methodological sophistication. Data elicitation techniques have evolved from global pronunciation ratings and grammaticality judgments to tests involving reaction times, acoustic measurements, eye-tracking, electrophysiological measurements, and neuro-imaging; and the effect of age on many aspects of pronunciation and grammar has been scrutinized in great detail, from voice onset time and vowel quality to subjacency and aspectual distinctions. Particularly rich empirical studies, with a large number of participants, encompassing both grammar and pronunciation, and showing that the effects of age of arrival (AoA) and other predictors can be quite different from one domain or subdomain of language to the other, are Flege ,et al., (1999) and Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam (2009) (see the section on empirical evidence for more detail on those studies). Recent book-length discussions of the age issue can be found in Herschensohn (2007) and Montrul (2008).

Core issues

The wealth of empirical research referred to in the previous section and described in more detail in the next section has not diminished the controversy surrounding the issue. The concept of “critical period” implies a declining learning capacity within a specific age range and a maturational, ultimately biological reason for this decline; both of these characteristics of a true critical period are absent in second language acquisition according to some researchers (e.g., Birdsong, 2005, 2009; Hakuta et al., 2003), and therefore “age effects” is often preferred as a more neutral term, referring to undeniable empirical facts with fewer theoretical implications than the term “critical period.” The main arguments against a “critical period” are the lack of clear causal mechanism of a biological nature (while there are many confounds with age differences, including input differences, increasing role of L1 influence with age, decreasing role of schooling with age, different patterns of socialization, and L1 vs. L2 use as a function of age of immigration) and the lack of agreement on clear onset or offset points for the “critical period.”

All these arguments are further complicated by a number of distinctions that are crucial for understanding the existing empirical findings, but that are often forgotten. First and foremost, a distinction needs to be made between speed of learning and ultimate attainment (see Han, Chapter 29, this volume, for the related notion of fossilization). What children are particularly good at is eventually reaching native-speaker levels, NOT learning faster than adults or adolescents. This distinction was clearly made already in Krashen et al. (1979) and is generally accepted now by researchers on age effects, yet often ignored in research design. Quite regularly studies are published that claim to “test the critical period hypothesis” but that investigate participants with only a couple of years of exposure to L2. After such a short period of exposure, the learners’ linguistic competence is still developing, which means that any measures taken then reflect speed of learning and not ultimate attainment, and hence cannot serve to “test the critical period hypothesis.” Particularly interesting, however, are studies that show, with the same learners tested at different points in time, how after limited amounts of exposure older learners do better, but after several more years younger starters get further ahead: Jia and Fuse (2007) and Larson-Hall (2008), the former with immigrants in the USA, the latter with classroom foreign language learners in Japan.

Next are two distinctions that overlap in most cases, but are not quite the same: formal (“instructed,”“tutored) learning versus naturalistic learning, and explicit versus implicit learning. As the quote from Lenneberg (1967) above suggests, adults are not any worse at learning grammar rules or vocabulary in explicit fashion than children, on the contrary; what they are worse at is learning the language through mere exposure and communicative interaction without reflecting on the language. Most classroom learning tends to rely quite a bit on reflecting on structure, and most non-tutored immigrants tend to do little such reflection; hence the two distinctions tend to coincide. They are not the same, however, as some classroom learners do get large amounts of exposure to and communicative practice in the L2 (particularly in immersion programs) and as some adult or adolescent learners, particularly those with above-average levels of education and/ or verbal ability, are likely to do quite a bit of reflection and explicit induction of patterns on their own. Needless to say, when the three distinctions coincide in the sense that research participants are tutored learners in a classroom that encourages explicit learning (learning with awareness of the structures being learned), and if their proficiency is tested after only a couple of years of L2 exposure, often only a few hours a week, then, all that is measured is speed of explicit learning, not ultimate attainment through implicit learning, and the data are irrelevant to the critical period debate (but not to the study of age effects, of course).

Further distinctions need to be made on the side of the dependent variable, proficiency in L2. Linguists traditionally distinguish phonology, morphosyntax, and lexicon (educators may prefer the largely equivalent terms pronunciation, grammar, and vocabulary), and it has often been observed that age effects are stronger in pronunciation than in grammar and barely noticeable in vocabulary; some even hypothesized that age effects were limited to pronunciation. Sufficient empirical evidence has accumulated now for strong age effects in both pronunciation and grammar, and at least some research suggests that (less obvious) effects exist in vocabulary (Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam, 2009; Hyltenstam, 1992; Silverberg and Samuel, 2004; pace Hirsh et al., 2003).

Increasingly, however, research has shown that more fine-grained distinctions need to be made to determine what aspects of language are affected by age of acquisition. Within pronunciation, e.g., Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam (2009) found that voice onset time was more affected by age than global accent rating. Within the area of grammar, e.g., Birdsong (1992), DeKeyser (2000), Johnson and Newport (1989), and McDonald (2006), among others, found that different morpho-syntactic structures showed different degrees of decline with increasing age of acquisition. DeKeyser et al. (forthcoming; cf., also DeKeyser, 2000) found that the less salient a morphological structure, the more sensitive it was to age effects; components of salience that interacted most strongly with age were stress on the morpheme to be acquired and distance between morphemes in agreement patterns. Within the area of vocabulary, susceptibility to priming (Silverberg and Samuel, 2004) and knowledge of idioms (Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam, 2009) stand out as being dependent on AoA, while vocabulary as a whole is generally assumed to show little or no effect of AoA.

A final point to keep in mind when reading the empirical literature on age effects is that the notion of nativelikeness is not entirely non-problematic (see esp. Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam, 2009; Birdsong, 2007, 2009). When rather easy tests of basic morphosyntax are used, they may lead to ceiling effects that hide aspects of non-nativeness that would become obvious with harder tests; these ceiling effects become more likely for younger learners, learners with an L1 close to the L2, and highly-educated learners, thus easily providing a distorted picture, because the degree of nonnativeness masked by the easy test depends on all these factors. When much harder tests are used, one may find that native speakers show quite a bit of variability on the structures at issue, as a function of social class, level of education, region of origin, and so on, which makes it very hard to determine the boundaries of nativeness; one will usually find a statistical difference between natives or young learners and older learners, but some of the better older learners are likely to fall “within native range” on some of the items or measures, given that the native range is so wide. Ideally, of course, one should use elements of grammar or pronunciation that are known to be quite hard for second language learners (with a given L1), but where native speaker variability is extremely minimal, such as the use of articles in English or the use of verbal aspect in the Romance or Slavic languages.

Taking all of these caveats into account, what does the empirical literature show? Nobody doubts that a strong negative correlation between AoA and ultimate attainment is found for many aspects of both grammar and pronunciation; nobody doubts either that some individuals often pass for native speakers in everyday interaction, even though they learned a language as an adult. Neither of these two observations have much to say about the existence of a critical period; the second one not even about age effects. In fact, a strong negative correlation between age of acquisition and ultimate attainment throughout the lifespan (or even from birth through middle age), the only age effect documented in many earlier studies, is not evidence for a critical period. As pointed out above, the critical period concept implies a break in the AoA-proficiency function, i.e., an age (somewhat variable from individual to individual, of course, and therefore an age range in the aggregate) after which the decline of success rate in one or more areas of language is much less pronounced and/or clearly due to different reasons.

On the other hand, more recent studies often do not calculate AoA-proficiency correlations separately for different age ranges (say, e.g., 0–6, 6–12, 12–18, 18–40, 40–60), but infer from the negative correlation over the lifespan that the correlation is equally negative and for the same reasons for each age range, and hence that there is no critical period. This is equally naïve as inferring there is a critical period from the same data. A mere (strong) negative correlation for the whole lifespan is not evidence for either of these inferences at all. Nor does the existence of people who can often pass for native speakers prove automatically that they are immune to critical period effects or any other age effects. Until it is shown that their nativelike appearance holds up under scrutiny, this appearance is just an appearance; in other words it merely shows that they are less strongly affected and/or that they found an alternative path to reaching the same observable skill.

A few studies claim to have found speakers who hold up under such scrutiny, even in the area of pronunciation (Bongaerts et al., 1995; Bongaerts et al., 1997; Bongaerts, 1999; Bongaerts et al., 2000; Birdsong, 2007). These studies have been criticized on a variety of methodological grounds, however (most notably by Long, 2005). Moreover, the largest and most careful study on this topic to date, Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam (2009), with carefully selected learners who were administered a set of difficult tests on grammar, pronunciation, and vocabulary, found that out of 195 participants with varying AoA who said they could pass for natives and 41 who were indeed deemed to be native by a panel of judges listening to a short speech sample, none with AoA > 8 scored within native speaker range on all 10 fine-grained measures (the maximum for any of these “older” learners was 7 measures out of 10); moreover those who passed for native on most tests were all highly educated language professionals, suggesting again that to the extent adult learners even come close to nativelikeness, it is only with the help of large amounts of explicit learning. Further evidence for this point of view comes from DeKeyser (2000) and Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam (2008), who showed that none of their adult learners scored within the native range, even by liberal standards, unless they had high levels of aptitude. Other studies, such as DeKeyser et al. (2010), and Harley and Hart (1997), provide evidence that aptitude plays a much larger role for adolescents and adults than for children, again pointing to a larger role for explicit learning in (successful) older learners. A more detailed account of the empirical evidence available is provided below.

Meanwhile, before delving more deeply into the literature, let us mention what is probably the most interesting but also the most contentious question of all, that of the causal interpretation of this whole body of research: are the age effects that are being documented with ever more precision for ever more populations and languages evidence of a maturational phenomenon or not? And if so, is that maturation sufficiently delimited in time to be called a critical period? If yes, what is its biological etiology? It is natural to think that neuro-imaging research and other areas of cognitive neuroscience are crucial for answering these questions, and progress is certainly being made in that area. There are two reasons, however, why the picture that emerges is far from clear. One is that the amount of research that has tried to pinpoint the exact nature of age-sensitive elements of language in (psycho)linguistic terms is quite limited (the vast majority of studies have only used broad distinctions, like phonology versus syntax); as a result, one does not even know exactly what to look for in neuroscience, i.e., what specific aspects of brain maturation may be responsible for changes in the capacity to learn those specific aspects of language. The other reason is that cognitive neuroscience data tend to be extremely variable from study to study and hard to interpret, let alone to predict. Predictive validity is still a distant goal in most neuro-imaging research (see e.g., Vul et al., 2009) and in the neuroscience of second language acquisition in particular (see e.g., de Bot, 2008), even though meta-analyses are beginning to allow some generalization (see e.g., Indefrey, 2006). As a result, the existing neuroscience literature on age effects in L2 (a summary of which can be found in Birdsong, 2006) largely aims at answering the same question as the behavioral research: what is the extent of age effects for specific aspects of language learning, and does any of this suggest a critical period, that is, a maturational, not a contextual, phenomenon? A specific biological etiology for the age effects found is seldom even suggested, let alone tested.

In summary, the core questions are whether there is a specific period of decline in the ability for implicit language learning, and whether any such decline is due to maturational factors. These questions sometimes lead to unnecessary confusion because of the failure to distinguish between implicit and explicit learning, between speed of learning and ultimate attainment, and between various aspects of language; not all aspects of grammar or even phonology are equally sensitive to age effects. In the next section, we discuss the various strands of research on these questions in more detail.

Data and common elicitation measures

While a wide variety of measures have been used to assess L2 proficiency in age effect studies, fairly global measures dominated at first: global accent ratings in the area of phonology (e.g., Asher and García, 1969; Oyama, 1978), grammaticality judgments with a wide variety of structures in the area of morphosyntax (e.g., Johnson and Newport, 1989; Patkowski, 1980). In both areas, more recent research has often narrowed its focus. Specific aspects of phonology have been investigated, such as voice onset time (Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam, 2009), vowel discrimination (Tsukada et al., 2005), and acoustic characteristics of consonant production (Kang and Guion, 2006), as well as specific aspects of grammar, such as subjacency (Johnson and Newport, 1991), verb aspect (Montrul and Slabakova, 2003), and adjective-noun agreement (Scherag et al., 2004).

At the same time, the testing format has often shifted from untimed paper-and-pencil tests to measures of reaction times, not only for priming experiments (e.g., Scherag et al., 2004), but also for grammaticality judgment tests (Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam, 2009). Still other measures have been used in the area of vocabulary, such as lexical decision tasks (Silverberg and Samuel, 2004), and oral fill-in-the-blanks (Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam, 2009).

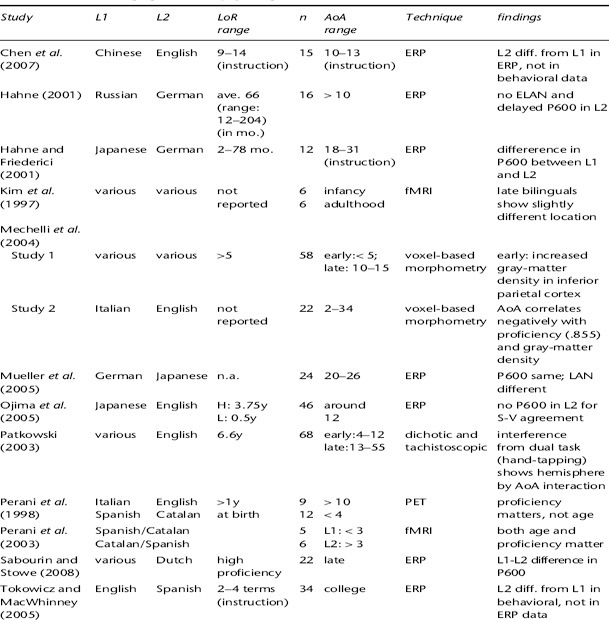

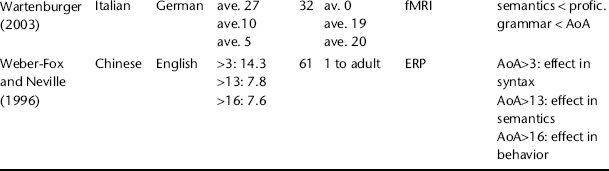

The last 15 years or so have seen an explosion of research in cognitive neuroscience, in this area as well as in others. Through fMRI and PET, researchers have tried to pinpoint areas in the brain that are maximally active during second language processing by adults who had learned an L2 at different ages (e.g., Perani et al., 1998, 2003; Wartenburger et al., 2003); even more recently, ERP has been used to trace the time course of the brain's reaction to correct and incorrect stimuli in the L2 as a function of AoA (e.g., Hahne, 2001; Weber-Fox and Neville, 1996) or to assess whether adult learners necessarily show different patterns from native speakers (e.g., Friederici et al., 2002; Ojima et al., 2005).

Finally, at the opposite end of the spectrum from the neuroscience research and the more fine-grained behavioral research, there is the census research. Almost all age effect studies that have collected their own data have limited reliability because they have too few subjects, maybe not in a general sense, but definitely for a robust analysis of age effects in narrow age ranges or when a number of covariates have to be partialed out. Therefore, researchers like Chiswick and Miller (2008), Hakuta et al. (2003), and Stevens (1999) have taken the opposite approach: use existing census data to establish a more reliable correlation between immigrants’ age of arrival and their linguistic proficiency. The problem in this case, of course, is not reliability but validity: self-assessments may have their value for certain types of research, but the extremely coarse scales used by the census, combined with the lack of reference point for the average census participant, casts serious doubts on the usefulness of this approach (DeKeyser, 2006; Stevens, 2004).

We next turn to empirical verification. Even though a variety of methodologies have been used for assessing age effects, as explained in the previous section, three clusters of studies stand out that have used the most frequently used methodologies: oral grammaticality judgment tests, other tests of morphosyntax (esp. written grammaticality judgment tests and global ratings of grammatical accuracy), and global accent ratings. For these three clusters of studies we provide a table with the most important variables and findings of the studies, and therefore provide less detail in the text. For all other methodologies we provide a more detailed discussion.

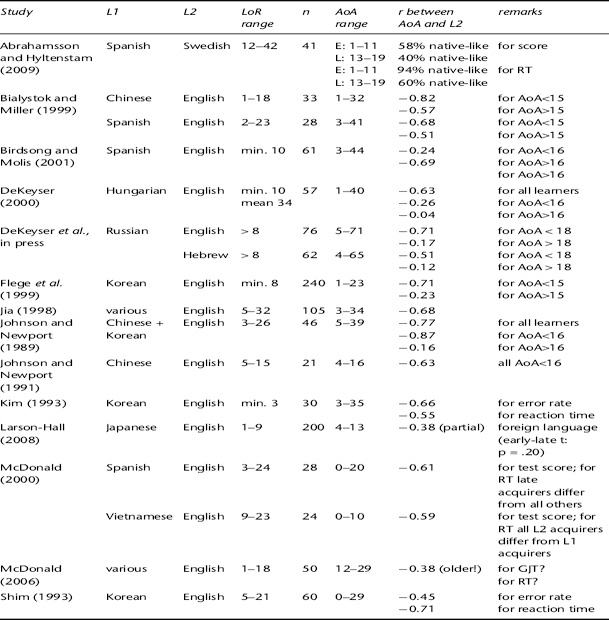

As Table 27.1 shows, the vast majority of studies that use GJTs (Grammaticality Judgment Tests) as the outcome variable have found large correlations between AoA and GJT scores. Global correlations for the entire lifespan (or at least the part included in the individual studies) range from |0.45| to |0.77| (correlations being negative for test scores, and positive for error rates or reaction time). For the younger groups (varying from study to study between AoA < 12 and AoA < 18) the correlation ranges from |0.24| to |0.87|; for the older groups from |0.04| to |0.69| (the vertical stripes refer to absolute value, and the values are negative where accuracy is concerned and positive where error rate is concerned). In those studies where the two groups are described separately, the correlation is much higher for the younger than for the older group, except in Birdsong and Molis (2001), where there was a ceiling effect for the younger group. This global picture from more than a dozen studies provides support for the non-continuity of the decline in the AoA-proficiency function, which all researchers agree is a hallmark of a critical period phenomenon. In other words, contrary to what some researchers have claimed, there is evidence for an upper age limit to the decline in implicit language learning ability, a limit which all agree is a necessary condition for the claim that the age effects observed are not simply a matter of lifelong decline.

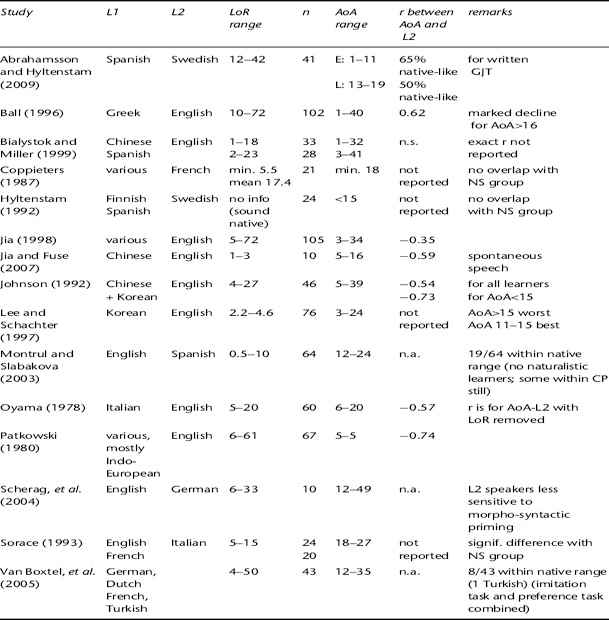

The results for other morphosyntactic measures in Table 27.2 show largely the same picture: where global correlations are given, they range from |0.35| to |0.74|; where group comparisons are made, learners with AoA > 15–16 are significantly worse than younger learners; for some studies there is even no overlap for the older learners with the native speaker range.

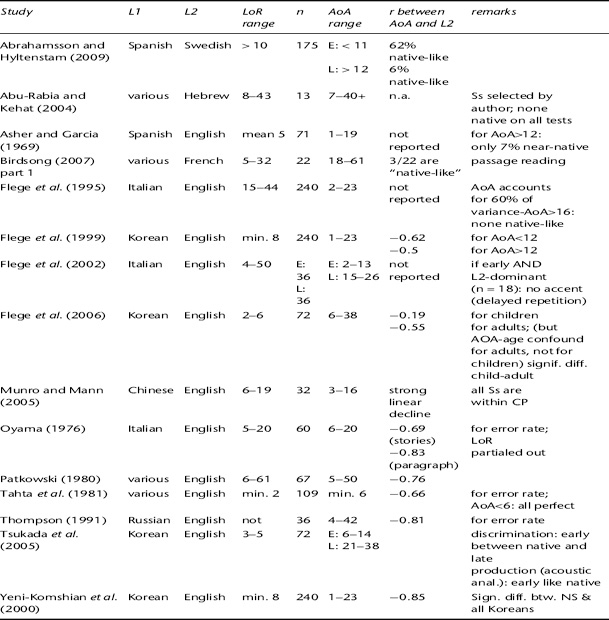

Table 27.3 shows that global accent ratings also yield high correlations for the entire lifespan (|0.66| to |0.85|) or for younger learners, the only exception being Flege et al. (2006), where AoA was strongly confounded with age at testing for the older, but not the younger group. Where group comparisons are made, younger learners always do significantly better than the older learners. The behavioral evidence, then, suggests a non-continuous age effect with a “bend” in the AoA-proficiency function somewhere between ages 12 and 16.

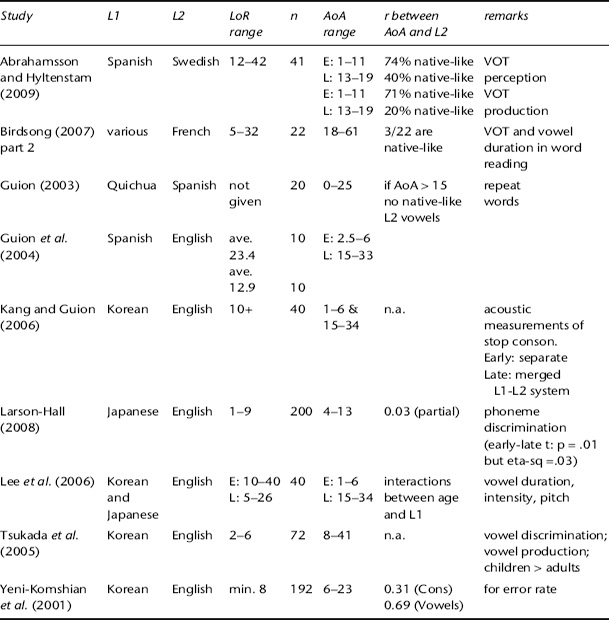

Further evidence for the effect of AoA on pronunciation comes from more narrowly focused investigations. As Table 27.4 shows, the approach taken in these studies varies widely: they examined production or perception, vowels or consonants, using human judgments or acoustic analyses; they included other variables that differed from study to study, such as length of residence (LOR) or L1/L2 dominance; they examined immigrants in some cases and classroom learners in others; some made group comparisons and others studied individuals’ performance. This makes it hard to come to any clear conclusions except that AoA seems to play a very significant role, but that it is often confounded with other variables, and that a few individuals can pass for native on some narrowly constrained tasks. The main point, however, is that there is no evidence of the AoA effect disappearing when other variables are taken into account, or of adult learners passing for native on a wide range of stringent tests.

The evidence from neuroscience is even more ambiguous in its findings and harder to summarize because of the great variety of tasks, measures, and outcomes (see Table 27.5). Some studies found clear qualitative differences between younger and older learners in the details of brain anatomy (Mechelli et al., 2004) or in the nature of L2 processing, as indicated by location and intensity of brain activity (Kim et al., 1997; Perani et al., 1996, 2003; Wartenburger et al., 2003; Weber-Fox and Neville, 1996); others did not find any qualitative differences (Perani et al., 1998), at least not when controlling for proficiency. Most brain studies provide only indirect evidence in the sense that they provide support for differences between L1 and L2 processing, even for advanced late learners, but they do not establish direct correlations with AoA (e.g., Hahne, 2001; Hahne and Friederici, 2001; Ojima et al., 2005; Sabourin and Stowe, 2008, all using ERP). Other studies are even harder to interpret because they deal with instructed learning (e.g., Chen et al., 2007), even short-term instructed learning (e.g., Mueller et al., 2005; Tokowicz and MacWhinney, 2005). Patkowski (2003), on the other hand, does make relevant age comparisons that show a clear difference between AoA < 12 and AoA > 12, but provides only indirect evidence about differential hemisphere involvement (behavioral evidence from a verbal-manual dual-task paradigm).

Table 27.1 Correlations between AoA and L2 proficiency as measured by oral grammaticality judgment tests

Table 27.2 Correlations between AoA and L2 proficiency as measured by other tests of morphosyntax

Table 27.3 Correlations between AoA and L2 proficiency as measured by global phonological ratings

Table 27.4 Other evaluations of pronunciation

If one accepts the argument that only comparisons between bilinguals are valid (otherwise instead of documenting age effects one may be modeling monolingual vs. bilingual effects, as demonstrated in Proverbio, Çok and Zani's 2002 ERP study; see also Byrnes, Chapter 31, this volume) and that to talk about age effects one should make direct age comparisons, not just compare late L2 learners to L1 speakers, few relevant studies exist. If one further rejects the results from studies that did not have any control for proficiency or years of exposure, one is left with only a handful of studies: Kim et al. (1997), Mechelli et al.(2004), Perani et al. (1998, 2003), Wartenburger et al. (2003), Weber-Fox and Neville (1996). All of these found a significant effect of AoA, except for Perani et al. (1998). If one adds to that the inescapable argument that not documenting any difference for a couple of structures does not mean there are none for other structures, the scant

Table 27.5 Neuro-imaging and neurophysiological measures

evidence we have so far does suggests qualitative differences in brain activity as a function of age, even when L1/L2 status and proficiency/exposure are controlled for.

Showing qualitative effects does not necessarily require brain imaging or ERP, however. Other researchers have tried to provide more indirect evidence (and for the learning processes rather than their end result) by investigating the different predictive validity of both learner and language variables in different age ranges. DeKeyser (2000), DeKeyser et al. (2010), and Harley and Hart (1997) all show that aptitude plays a much more important role in L2 acquisition for adolescents and adults than for children; Abrahamsson and Hyltenstam (2008) and DeKeyser (2000) both showed that no adult learners fell within the native proficiency range unless they had high aptitude. Such findings suggest a larger role of explicit/declarative learning in older than in younger learners (cf., also Bley-Vroman, 2009; Montrul, 2009; Paradis 2004, 2009; Ullman, 2001, 2004). The interaction between the salience of linguistic structures and AoA as documented in DeKeyser et al. (forthcoming) also points in that direction, given that salience is known to play a much larger role in explicit than in implicit learning (Reber et al., 1980).

The literature on L1 attrition/incomplete acquisition is also of potential relevance here. Not only does attrition, “the non-pathological decrease in a language that had previously been acquired by an individual” (Köpke and Schmid, 2004), show the reverse pattern of L2 acquisition in the sense that the earlier the switch is made from L1 (dominance) to L2 (dominance), the less remains of L1; it is becoming increasingly clear that this age effect in attrition is a maturational effect in the sense that it is due to lack of input at a critical age (Bylund, 2009a, b; Hyltenstam et al., 2009; Montrul, 2008; Schmid, 2009) rather than lack of continued practice later on.

The attrition research is also relevant to two more specific questions: the issue of the role of L1 “entrenchment” (e.g., MacWhinney, 2006) in the increasingly incomplete acquisition of L2 with increasing AoA/L1 development, and the much-debated issue of the non-continuity of the AoA function. Research with adoptees (Pallier et al., 2003; Ventureyra et al., 2004) is often quoted as showing that when there is zero interference from the L1 (because L1 is completely lost), then L2 is acquired 100 percent, and some have used this as an argument for the interpretation of (the lack of) incomplete acquisition of L2 as due to (the lack of) L1 entrenchment. Oh et al. (2010), however, report traces of phoneme recognition in adults who were adopted at a very young age, and Hyltenstam et al. (2009) show that neither complete L1 loss nor complete L2 acquisition are necessarily found in children adopted at a very young age, but that small traces of L1 do remain, as well as traces of non-nativeness in L2. Perhaps one could argue that this is just another example of L1 and L2 being proportionately lost/acquired, if not 100 percent, as in Pallier et al. (2003) or Ventureyra et al. (2004), then at least close to 100 percent, but that does not account for an important fact from research on sign language acquired as L1 at different ages. Mayberry (1993), e.g., shows that age effects on American Sign Language (ASL) as L1 (in congenitally deaf children of hearing parents) are similar to age effects on ASL as L2 (in those who become deaf later or for some other reason learn ASL as L2). Clearly, age effects in L1, by definition, cannot be due to entrenchment of a previously acquired language, and therefore Occam's razor requires us to think twice before trying to explain age effects in L2 with arguments about L1 interference.

The non-continuity debate has pitted researchers such as Johnson and Newport (1989) and DeKeyser et al. (2010), who worked with linguistic data elicited specifically for age effect research and found non-continuous effects of AoA, leveling off in early adolescence, against others such as Bialystok and Hakuta (1994, Hakuta et al., 2003) and Chiswick and Miller (2008), who used self-ratings retrieved from census data and found a continuous, lifelong decline. Here again, research on L1 attrition provides important evidence: Schmid (2002) found no difference in attrition when comparing adolescent learners to adult learners, in contrast with the various aforementioned findings about attrition in pre-puberty learners, suggesting non-continuity in attrition, not just in acquisition.

In conclusion then, the preponderance of the evidence on the acquisition of phonology and morphosyntax, both behavioral and neurological, as well as the literature on attrition, strongly support non-continuous age effects of a qualitative nature. Little is known, however, about the biological aspects of these changes. For discussion of possible explanations in psychological terms, see DeKeyser and Larson-Hall (2005).

Applications

As pointed out in the historical section of this chapter, research on age effects in language learning has always provided a strong impetus for early teaching; the work of Penfield and Roberts (1959) was instrumental in starting the immersion program movement in Canada, soon to be followed by a push for foreign language in the elementary school (FLES) in the USA and many other countries. This push for earlier foreign language teaching is still going on today, particularly in Asia.

It should be pointed out, however, that “earlier is better” when it comes to L2 learning, does not necessarily imply that “earlier teaching is better.” Virtually all the research quoted in the previous sections was carried out with immigrants who are fully immersed in a second language environment and who may or may not have received any instruction in it. In a school context we have the opposite situation: plenty of instruction, but very little exposure, except of course in true immersion programs. Moreover, the quality of the input may be diminished by various factors such as the artificiality of classroom interaction (even assuming it is always in the L2, a big assumption for most elementary foreign language instruction) and the often far-from-perfect proficiency of non-native teachers, especially in the area of pronunciation.

We know that children are better than adults at acquiring an L2 (a) in the long run from (b) massive amounts of (c) native-speaker input, but does that mean that (a) after just a few years of instruction (b) provided only a few hours per week and not every week in the year by (c) non-native teachers with sometimes very limited proficiency, children will do better than adults too? Of course, students who have had several years of L2 instruction in grade school and middle school before going on with the same language in high school will know more than those who only start in high school, but that does not say anything about age, only about amount of instruction. Given the same amount of the same kind of instruction at an earlier age, do students learn more? That is a question that has been addressed by surprisingly little research, especially given the enormity of its implications for educational systems worldwide.

Almost all empirical research carried out in an attempt to answer that question has been conducted in Spain. Muñoz (2008) provides a summary and comes to the clear conclusion that “older is better,” except perhaps for pronunciation. As always, the picture is not 100 percent clear, because this research almost inevitably suffers from a design flaw in the sense that younger learners being tested after the same amount of instruction as older learners are simply younger when tested, and therefore less adept at taking tests. Given our interpretation of the nature of age effects above, however, i.e., that they reflect a shift from predominantly implicit to predominantly explicit learning processes, the results described in Muñoz (2008) are to be expected.

More indirect evidence also exists for the view that, instead of a mere quantitative change in the sense of declining learning capacity with increasing age of arrival, what really takes place is a qualitative shift from implicit to explicit learning. Studies that provide a broad view on the language development of immigrant children such as Tarone et al., (2009) show the important role of metalinguistic awareness and explicit learning in older children, while more focused studies such as White (2008) and Alcón Soler and García Mayo (2008) provide evidence of the efficiency of age-appropriate focus on form.

Future directions

Research on age effects has only begun. We need much more documentation of what aspects of language become harder to learn at what age, and much more research on the immediate and ultimate causes. One avenue to pursue is a wider variety of more sophisticated measures, whether they be of the neurophysiological or neuro-imaging kind or “simply” involve clever use of behavioral measures elicited under laboratory conditions, involving reaction time measurements, priming conditions, eye tracking, and so on.

Two other avenues are less technical in nature, but no less important. We need research with a wider variety of source and target languages, preferably in the same study, in order to be able to generalize in more abstract terms what kinds of features of language become harder to learn with age. Most importantly of all, however, we need much better samples. All participants in AoA studies should have had a fair chance to develop native-like proficiency in L2. That means, among other things, a length of exposure of at least five, ideally ten years, so that we can observe ultimate attainment and not just speed of learning (because empirical evidence shows that learners asymptote after ten years for just about any area of language, except vocabulary), and learners who have spent almost all this time interacting in the L2—a condition virtually no study has met so far, because we all tend to use samples of convenience consisting of participants drawn from sizable immigrant communities (close to our universities), where L1 use is quite common. Combining the requirement of having largely isolated speakers with the obvious statistical requirement of having bigger samples than is typically the case, is one of the greatest challenges in this area. Obtaining large samples of largely isolated learners, preferably native speakers of an L1 that is distant from the L2, should be a goal we can all agree on, whether we think age effects are maturational or not.

References

Abrahamsson, N., and Hyltenstam, K. (2008). The robustness of aptitude effects in near-native second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 30(4), 481–509.

Abrahamsson, N. and Hyltenstam, K. (2009). Age of onset and nativelikeness in a second language: Listener perception versus linguistic scrutiny. Language Learning, 59(2), 249–306.

Alcón Soler, E. and García Mayo, M. D. P. (2008). Incidental focus on form and learning outcomes with young foreign language classroom learners. In J. Philp, R. Oliver, and A. Mackey (Eds.), Second language acquisition and the younger learner: Child's play? (pp. 173–192). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Asher, J. J. and García, R. (1969). The optimal age to learn a foreign language. The Modern Language Journal, 53, 334–341.

Ball, J. (1996). Age and natural order in second language acquisition. Unpublished Ed. D., University of Rochester.

Benzaquén, A. S. (2006). Encounters with wild children. Temptation and disappointment in the study of human nature. Montreal, Canada: McGill-Queen's University Press.

Bialystok, E. and Hakuta, K. (1994). In other words: The science and psychology of second-language acquisition. New York: BasicBooks.

Bialystok, E. and Miller, B. (1999). The problem of age in second-language acquisition: Influences from language, structure, and task. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 2(2), 127–145.

Birdsong, D. (1992). Ultimate attainment in second language acquisition. Language, 68(4), 706–755.

Birdsong, D. (2005). Interpreting age effects in second language acquisition. In J. F. Kroll and A. M. B. de Groot (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches (pp. 109–127). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Birdsong, D. (2006). Age and second language acquisition and processing: A selective overview. Language Learning, 56 (Supplement 1), 1–49.

Birdsong, D. (2007). Nativelike pronunciation among late learners of French as a second language. In O. -S. Bohn and M. J. Munro (Eds.), Language experience in second language learning. In honor of James Emil Flege (pp. 99–116). Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Birdsong, D. (2009). Age and the end state of second language acquisition. In T. Bhatia and W. Ritchie (Eds.), The new handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 401–424). Bingley: Emerald.

Birdsong, D. and Molis, M. (2001). On the evidence for maturational constraints in second-language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language, 44, 235–249.

Bley-Vroman, R. (1988). The fundamental character of foreign language learning. In W. Rutherford and M. Sharwood Smith (Eds.), Grammar and second language teaching: A book of readings (pp. 19–30). New York: Newbury House.

Bley-Vroman, R. (2009). The evolving context of the fundamental difference hypothesis. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 31(2), 175–198.

Bongaerts, T. (1999). Ultimate attainment in L2 pronunciation: The case of very advanced late L2 learners. In D. Birdsong (Ed.), Second language acquisition and the critical period hypothesis (pp. 133–159). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bongaerts, T., Mennen, S., and van der Slik, F. (2000). Authenticity of pronunciation in naturalistic second language acquisition: The case of very advanced late learners of Dutch as a second language. Studia Linguistica, 54(2), 298–308.

Bongaerts, T., Planken, B., and Schils, E. (1995). Can late learners attain a native accent in a foreign language? A test of the critical period hypothesis. In D. Singleton and Z. Lengyel (Eds.), The age factor in second language acquisition (pp. 30–50). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Bongaerts, T., van Summeren, C., Planken, B., and Schils, E. (1997). Age and ultimate attainment in the pronunciation of a foreign language. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(4), 447–465.

Bylund, E. (2009a). Maturational constraints and first language attrition. Language Learning, 59(3), 687–715.

Bylund, E. (2009b). Effects of age of L2 acquisition on L1 event conceptualization patterns. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 12(3), 305–322.

Chen, L., Shu, H., Liu, Y., Zhao, J., and Li, P. (2007). ERP signatures of subject-verb agreement in L2 learning. Bilingualism: Language and cognition, 10(2), 161–174.

Chiswick, B. R. and Miller, P. W. (2008). A test of the critical period hypothesis for language learning. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 29(1), 2008.

Coppieters, R. (1987). Competence differences between native and near-native speakers. Language, 63, 544–573.

de Bot, K. (2008). The imaging of what in the multilingual mind? Second Language Research, 24(1), 111–133.

DeKeyser, R. M. (2000). The robustness of critical period effects in second language acquisition. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 22(4), 499–533.

DeKeyser, R. M. (2006). A critique of recent arguments against the critical period hypothesis. In C. Abello-Contesse, R. Chacón-Beltrán, M. D. López-Jiménez, and M. M. Torreblanca-López (Eds.), Age in L2 acquisition and teaching (pp. 49–58). Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

DeKeyser, R. M., Alfi-Shabtay, I. and Ravid, D. (2010). Cross-linguistic evidence for the nature of age effects in second language acquisition. Applied Psycholinguistics, 31(3), 413–438.

DeKeyser, R. M., Alfi-Shabtay, I. and Ravid, D., and Shi, M. (forthcoming). The role of salience in the acquisition of Hebrew as a second language.

DeKeyser, R. M. and Larson-Hall, J. (2005). What does the critical period really mean? In J. F. Kroll and A. M. B. de Groot (Eds.), Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches (pp. 89–108). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Flege, J. E., Birdsong, D., Bialystok, E., Mack, M., Sung, H., and Tsukada, K. (2006). Degree of foreign accent in English sentences produced by Korean children and adults. Journal of Phonetics, 34(2), 153–175.

Flege, J. E., Mackay, I. R. A., and Piske, T. (2002). Assessing bilingual dominance. Applied Psycholinguistics, 23(4), 567–598.

Flege, J. E., Munro, M. J., and MacKay, I. R. (1995). Factors affecting strength of perceived foreign accent in a second language. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 97(5), 3125–3138.

Flege, J. E., Yeni-Komshian, G. H., and Liu, S. (1999). Age constraints on second-language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language, 41(1), 78–104.

Friederici, A. D., Steinhauer, K., and Pfeifer, E. (2002). Brain signatures of artificial language processing: Evidence challenging the critical period hypothesis. PNAS, 99(1), 529–534.

Guion, S. G. (2003). The vowel systems of Quichua-Spanish bilinguals. Age of acquisition effects on the mutual influence of first and second languages. Phonetica, 60, 98–128.

Guion, S. G., Harada, T., and Clark, J. J. (2004). Early and late Spanish-English bilinguals’ acquisition of English word stress patterns. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 7, 207–226.

Hahn, W. K. (1987). Cerebral lateralization of function: From infancy through childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 376–392.

Hahne, A. (2001). What's different in second-language processing? Evidence from event-related brain potentials. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 30(3), 251–266.

Hahne, A. and Friederici, A. D. (2001). Processing a second language: Late learners’ comprehension mechanisms as revealed by event-related brain potentials. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 4(2), 123–141.

Hakuta, K., Bialystok, E., and Wiley, E. (2003). Critical evidence: A test of the critical-period hypothesis for second-language acquisition. Psychological Science, 14(1), 31–38.

Harley, B. and Hart, D. (1997). Language aptitude and second language proficiency in classroom learners of different starting ages. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 19(3), 379–400.

Herschensohn, J. (2007). Language development and age. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Hirsh, K., Morrison, C. M., Gaset, S., and Carnicer, E. (2003). Age of acquisition and speech production in L2. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 6(2), 117–128.

Hyltenstam, K. (1992). Non-native features of near-native speakers: On the ultimate attainment of childhood L2 learners. In R. J. Harris (Ed.), Cognitive processing in bilinguals (pp. 351–368). Amsterdam and New York: Elsevier.

Hyltenstam, K., Bylund, E., Abrahamsson, N., and Park, H.-S. (2009). Dominant-language replacement: The case of international adoptees. Bilingualism: Language and cognition, 12(2), 121–140.

Indefrey, P. (2006). A meta-analysis of hemodynamic studies on first and second language processing: Which suggested differences can we trust and what do they mean? Language Learning, 56(1), 279–304.

Jia, G. and Fuse, A. (2007). Acquisition of English grammatical morphology by native Mandarin-speaking children and adolescents: Age-related differences. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 50, 1280–1299.

Johnson, J. S. and Newport, E. L. (1989). Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognition, 39, 215–238.

Johnson, J. S. and Newport, E. L. (1991). Critical period effects on universal properties of language: The status of subjacency in the acquisition of a second language. Cognitive Psychology, 21, 60–99.

Kang, K.-H. and Guion, S. G. (2006). Phonological systems in bilinguals: Age of learning effects on the stop consonant systems of Korean-English bilinguals. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 119(3), 1672–1683.

Kim, R. (1993). A sensitive period for second language acquisition: A reaction-time grammaticality judgment task with Koren-English bilinguals. IDEAL, 6, 15–27.

Kim, K. H. S., Relkin, N. R., Lee, K.-M., and Hirsch, J. (1997). Distinct cortical areas associated with native and second languages. Nature, 388, 171–174.

Krashen, S. D., Long, M. A., and Scarcella, R. C. (1979). Age, rate, and eventual attainment in second language acquisition. TESOL Quarterly, 13(4), 573–582.

Köpke, B. and Schmid, M. S. (2004). Language attrition: The next phase. In M. S. Schmid, B. Köpke, M. Keijzer, and L. Weilemar (Eds.), First Language Attrition.Interdisciplinary perspectives on methodological issues (pp. 1–43). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Larson-Hall, J. (2008). Weighing the benefits of studying a foreign language at a younger starting age in a minimal input situation. Second Language Research, 24(1), 35–63.

Lee, B., Guion, S. G., and Harada, T. (2006). Acoustic analysis of the production of unstressed English vowels by early and late Korean and Japanese bilinguals. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(3), 487–513.

Lee, D. and Schachter, J. (1997). Sensitive period effects in binding theory. Language acquisition, 6(4), 333–362.

Lenneberg, E. H. (1967). Biological foundations of language. New York: Wiley.

Long, M. (2005). Problems with supposed counter-evidence to the Critical Period Hypothesis. IRAL, 43(4), 287–316.

MacWhinney, B. (2006). Emergent fossilization. In Z. Han and T. Odlin (Eds.), Studies of fossilization in second language acquisition (pp. 134–156). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Marzi, C. A. (1996). Lateralization. In J. G. Beaumont, P. M. Keneally, and M. J. C. Rogers (Eds.), The Blackwell dictionary of neuropsychology (pp. 437–443). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Mayberry, R. I. (1993). First-language acquisition after childhood differs from second language acquisition: The case of American sign language. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 36, 1258–1270.

McDonald, J. L. (2000). Grammaticality judgments in a second language: Influences of age of acquisition and native language. Applied Psycholinguistics, 21(3), 395–423.

McDonald, J. L. (2006). Beyond the critical period: Processing-based explanations for poor grammaticality judgment performance by late second language learners. Journal of Memory and Language, 55, 381–401.

Mechelli, A., Crinion, J. T., Noppeney, U., O'Doherty, J., Ashburner, J., and Frackowiak, R. S. (2004). Structural plasticity in the bilingual brain. Nature, 431, 757.

Montrul, S. A. (2008). Incomplete acquisition in bilingualism: Re-examining the age factor. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Montrul, S. A. (2009). Reexamining the fundamental difference hypothesis: What can early bilinguals tell us? Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 31(2), 225–257.

Montrul, S. and Slabakova, R. (2003). Competence similarities between native and near-native speakers: An investigation of the preterite-imperfect contrast in Spanish. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 25(3), 351–398.

Mueller, J. L., Hahne, A., Fujii, Y., and Friederici, A. D. (2005). Native and nonnative speakers’ processing of a miniature version of Japanese as revealed by ERPs. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(8), 1229–1244.

Munro, M. and Mann, V. (2005). Age of immersion as a predictor of foreign accent. Applied Psycholinguistics, 26, 311–341.

Muñoz, C. (2008). Symmetries and asymmetries of age effects in naturalistic and instructed L2 learning. Applied Linguistics, 29(4), 578–596.

Oh, J. S., Au, T. K.-F., and Jun, S.-A. (2010). Early childhood language memory in the speech perception of international adoptees. Journal of Child Language, 37(5), 1123–1132.

Ojima, S., Nakata, H., and Kakigi, R. (2005). An ERP study of second language learning after childhood: Effects of proficiency. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(8), 1212–1228.

Oyama, S. (1978). The sensitive period and comprehension of speech. Working papers in bilingualism, 16, 1–17.

Pallier, C., Dehaene, S., Poline, J.-B., LeBihan, D., Argenti, A.-M., and Dupoux, E. (2003). Brain imaging of language plasticity in adopted adults: Can a second language replace the first? Cerebral Cortex, 13, 155–161.

Paradis, M. (2004). A neurolinguistic theory of bilingualism. Philadelphia: Benjamins.

Paradis, M. (2009). Declarative and procedural determinants of second languages. Amsterdam: Benjamins. Patkowski, M. S. (1980). The sensitive period for the acquisition of syntax in a second language. Language Learning, 30, 449–472.

Patkowski, M. (2003). Laterality effects in multilinguals during speech production under the concurrent task paradigm: Another test of the age of acquisition hypothesis. IRAL - International Review of Applied Linguistics in Language Teaching, 41, 175–200.

Penfield, W. and Roberts, L. (1959). Speech and brain-mechanisms. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Perani, D., Abutalebi, J., Paulesu, E., Brambati, S., Scifo, P., and Cappa, S. F. (2003). The role of age of acquisition and language usage in early, high-proficient bilinguals: An fMRI study during verbal fluency. Human Brain Mapping, 19, 170–182.

Perani, D., Dehaene, S., Grassi, F., Cohen, L., Cappa, S., and Dupoux, E. (1996). Brain processing of native and foreign languages. Neuroreport, 7, 2439–2444.

Perani, D., Paulesu, E., Galles, N. S., Dupoux, E., Dehaene, S., and Bettinardi, V. (1998). The bilingual brain: Proficiency and age of acquisition of the second language. Brain, 121, 1841–1852.

Proverbio, A. M., Çok, B., and Zani, A. (2002). Electrophysiological measures of language processing in bilinguals. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 14(7), 994–1017.

Reber, A., Kassin, S., Lewis, S., and Cantor, G. (1980). On the relationship between implicit and explicit modes in the learning of a complex rule structure. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory, 6, 492–502.

Rymer, R. (1992). A Silent Childhood. The New Yorker, 13 April 1992 and 20 April 1992, Part 1 41–76, Part 42 43–77.

Sabourin, L. and Stowe, L. A. (2008). Second language processing: When are first and second languages processed similarly. Second Language Research, 24(3), 397–430.

Scherag, A., Demuth, L., Rösler, F., Neville, H. J., and Röder, B. (2004). The effects of late acquisition of L2 and the consequences of immigration on L1 for semantic and morpho-syntactic language aspects. Cognition, 93, B97–B108.

Schmid, M. S. (2002). First language attrition, use, and maintenance: The case of German Jews in Anglophone countries. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Schmid, M. S. (2009). L1 attrition across the lifespan. In K. de Bot and R. W. Schrauf (Eds.), Language development over the lifespan (pp. 171–188). London: Routledge.

Shim, R. J. (1993). Sensitive periods for second language acquisition: A reaction-time study of Korean-English bilinguals. IDEAL, 6, 43–64.

Silverberg, S. and Samuel, A. G. (2004). The effect of age of second language acquisition on the representation and processing of second language words. Journal of Memory and Language, 51, 381–398.

Sorace, A. (1993). Incomplete vs. divergent representations of unaccusativity in non-native grammars of Italian. Second Language Research, 9(1), 22–47.

Stevens, G. (1999). Age at immigration and second language proficiency among foreign-born adults. Language in Society, 28, 555–578.

Stevens, G. (2004). Using census data to test the critical-period hypothesis for second-language acquisition. Psychological Science, 15(3), 215–216.

Tahta, S., Wood, M., and Loewenthal, K. (1981). Foreign accents: Factors relating to transfer of accent from the first language to a second language. Language and Speech, 24(3), 265–272.

Tarone, E., Bigelow, M., and Hansen, K. (2009). Literacy and second language oracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Thompson, I. (1991). Foreign accents revisited: The English pronunciation of Russian immigrants. Language Learning, 41(2), 177–204.

Tokowicz, N. and MacWhinney, B. (2005). Implicit and explicit measures of sensitivity to violations in second language grammar: An event-related potential investigation. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 27(2), 173–204.

Tsukada, K., Birdsong, D., Bialystok, E., Mack, M., Sung, H., and Flege, J. E. (2005). A developmental study of English vowel production and perception by native Korean adults and children. Journal of Phonetics, 33, 263–290.

Ullman, M. T. (2001). The neural basis of lexicon and grammar in first and second language: The declarative/ procedural model. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 4, 105–122.

Ullman, M. T. (2004). Contributions of memory circuits to language: The declarative/procedural model. Cognition, 92, 231–270.

Ullman, M. T. (2005). A cognitive neuroscience perspective on second language acquisition: The declarative/procedural model. In C. Sanz (Ed.), Mind and context in adult second language acquisition (pp. 141–178). Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

Ventureyra, V. A. G., Pallier, C., and Yoo, H. -Y. (2004). The loss of first language phonetic perception in adopted Koreans. Journal of Neurolinguistics, 17, 79–91.

Vul, E., Harris, C., Winkielman, P., and Pashler, H. (2009). Reply to comments on “Puzzlingly high correlations in fMRI studies of emotion, personality, and social cognition”. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(3), 319–324.

Wartenburger, I., Heekeren, H. R., Abutalebi, J., Cappa, S. F., Villringer, A., and Perani, D. (2003). Early setting of grammatical processing in the bilingual brain. Neuron, 37, 159–170.

Weber-Fox, C. M., and Neville, H. J. (1996). Maturational constraints on functional specializations for language processing: ERP evidence in bilingual speakers. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 8, 231–256.

White, J. (2008). Speeding up acquisition of his and her: Explicit L1/L2 contrasts help. In J. Philp, R. Oliver, and A. Mackey (Eds.), Second language acquisition and the younger learner: Child's play? (pp. 193–228). Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Yeni-Komshian, G., Flege, J. E., and Liu, S. (2000). Pronunciation proficiency in the first and second languages of Korean-English bilinguals. Bilingualism: Language and Cognition, 3(2), 131–149.

Yeni-Komshian, G., Robbins, M., and Flege, J. E. (2001). Effects of word class differences on L2 pronunciation accuracy. Applied Psycholinguistics, 22(3), 283–299.

van Boxtel, S., Bongaerts, T., and Coppen, P.-A. (2005). Native-like attainment of dummy subjects in Dutch and the role of the L1. IRAL, 43, 355–380.