A Simulacrum of Celestial Order

The celestial host surrounding medieval Metz maintained an otherworldly permanency. On Bede’s own authority, the realm of the fixed stars and the planetary wanderers would survive the Apocalypse, bathed in the radiant splendor of the Almighty, who purged the unclean with fire. In chapter 70 of De temporum ratione, Bede had informed Drogo and all learned Franks that prior to the donning of “everlasting bodies,” “the airy heaven will shrivel up in fire, [but the heaven] of the stars will remain undamaged. In fact, the heavenly bodies will be darkened, not by being drained of their light, but by the force of a greater light at the coming of the Supreme Judge.”1 The texts and images of the fixed stars in a book such as Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 were signs of stability in a world of transience. Even the hope and promise of the Apocalypse, which played a fundamental role in the evangelistic mission and doctrine of renewal within the early medieval church, could not undermine these integral components of God’s observable creation. Time was consistently restored through the annual and daily cycles of the heavenly bodies, regulated by the sun and moon.2

For the Frankish princes who owned copies, the combined moments of meditative reflection upon the texts and star pictures of the Handbook of 809 were part of the unfolding salvation history of the Franks. Individual episcopal study by a prelate such as Drogo indirectly helped fulfill the soteriological mandates of the early medieval Christian church that called for sacred study of the liberal art of astronomy.3 Drogo’s personal copy of the Handbook of 809 was thus an ephemeral portal—bound for destruction within the Apocalyptic flames of penitence—that nevertheless opened his mind and spirit to the eternal mysteries of the heavens.

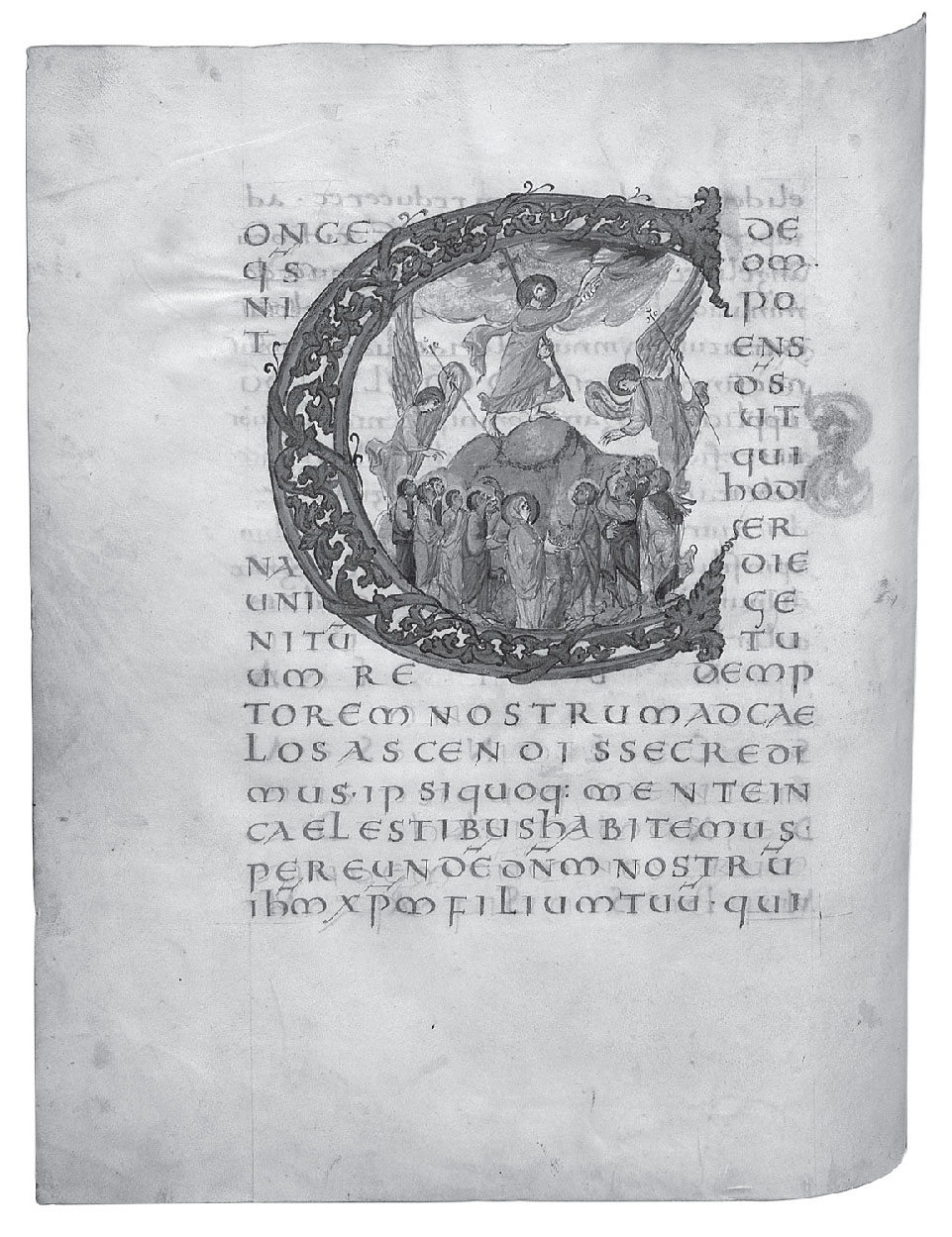

Paul Edward Dutton has argued in this context that courtly encomia likening worthy bishops to stellar vicars of Christ had more than a literary significance, operating as a topos for a poet such as Sedulius Scottus (fl. ca. 840–60) within the Frankish realm. Frankish kings such as Charlemagne or Louis the Pious achieved a veritable “Christianized Carolingian apotheosis” that could be extended by royal blood to their episcopal sons, nephews, and cousins, legitimate or otherwise, in service to the church.4 As Dutton notes, Sedulius, apparently an itinerant Irish monk, celebrated Bishop Hartgar (served 840–55), under whom he had served in Liège, perhaps achieving the rank of scholasticus (roughly equivalent to a headmaster) within Hartgar’s cathedral school dedicated to Saint Lambert.5 It is highly likely that Sedulius also composed a number of lyrical panegyrics in Metz for Bishop Adventius (served 858–75).6 Sedulius specifically makes Hartgar “earth’s most radiant star,” handpicked by Aurora in one poem,7 and in another compares the physical ascent of a tower to the expansion of the prelate’s mind, making the fulfillment of his episcopal and homiletic duties to the people of Liège possible:

The daughter of Zion rejoices in such a shepherd, and the rich and poor exult with joy.

He builds a lofty tower, a hundred cubits high, so that he may ascend above the stars.

Climbing the stairway rising towards heaven, he instructs his flock with sage words and examples.8

Drogo, similarly preparing himself through study of his personal copy of the Handbook of 809, thereby “wards off wolves and rescues his lambs.”9 It is within this framework, joining personal spiritual study to the establishment of a celestial Carolingian hagiography, that the text-image relationship in the Handbook of 809 must be addressed, and Drogo’s personal book is the best example of an official spiritual-yet-scientific manual disseminated throughout the Frankish realms for such use. Stephen McCluskey has said of such “astronomical and computistical anthologies,” otherwise known as “star catalogues,” that “their goal was not astronomical observation but artistic and mythological edification.”10 More important, study of the stars brought Carolingian bishops into the heavenly realms, where the planets and fixed stars served as stepping stones to intellectual freedom and spiritual enlightenment, purifying the hearts of these prelates while simultaneously preparing them to accomplish their spiritual mission on earth by bringing their fellow Franks along with them.11

In this chapter, the central theme of part 1 of the present volume continues to unfold: the art-historical significance of Drogo’s personal copy of the Handbook of 809 requires an investigation into the iconographic history of classically inspired but notably reinterpreted images of the heavens. This chapter focuses primarily on a detailed review of the pictorial program of constellations in Drogo’s handbook. After an initial explanation of Aratean traditions, I offer a complete iconographic analysis of the Greco-Roman traditions that informed the symbolic properties of the miniatures in Drogo’s handbook. In addition, specific attention is given to images such as Chiron the Centaur in order to supply a cogent example of Carolingian exegetical emendation and strongly advocate for Carolingian painterly creativity, as argued in the introduction. As seen in chapter 1, a thorough examination of Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 permits a celebration of the ways in which students of astronomy and computus created a dynamic record of their spiritual science.

Here in chapter 2, the profound appreciation for classical iconographic traditions manifested by the Carolingian prelates and painters who created Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 is contextualized, in terms of both the mythological narratives informing image types and the scientific soteriological benefits of studying the star pictures along with their corresponding texts. In every viable instance, Frankish painters demonstrated an appreciation of the traditions they transformed, creating a novel Christian presentation of the heavens one constellation at a time. At the end of this review, some closing remarks concerning Panofskian iconographic traditions build upon the comments in the introduction and conclude part 1.

History of the Aratean Pictorial Cycles and Their Texts

This novel spiritual justification for the Carolingian star catalogues supplied the impetus for the original description of the constellations offered to readers of the De ordine, which was systematically derived from an admixture of mythological lore and the presentation of the constellations modeled after star globes. The textual and visual considerations of vital significance for the De ordine hark back to Aratus of Soli, who came to Pella in 276 B.C.E. and composed the Phaenomena at the Macedonian court of Antigonus Gonatas, ca. 276–274 B.C.E.12 According to a somewhat apocryphal legend, Aratus did not derive his poetic description of the constellations, their stellar utility for discerning temporal changes, or their meteorological significance directly from the heavens.13 According to Cicero, Aratus was a well-trained literary dilettante from Athens without professional astronomical skills: “Eudoxus of Cnidos, who was a pupil of Plato’s . . . marked on the globe the stars that are fixed in the sky. Many years after Eudoxus, Aratus adopted from him the entire detailed arrangement of the globe and described it in verse, not displaying any knowledge of astronomy but showing considerable poetical skill.”14

Douglas Kidd has valiantly defended Aratus against such Ciceronian naysayers, arguing persuasively that Aratus neither imported wholesale nor uncritically endorsed Eudoxus’s interpretation of Greek astronomy. On the contrary, Aratus fundamentally altered the perspective from which he drafted his 1,154 lines of polished verse, adopting the standpoint of the stargazer and earthbound student of the heavenly host.15 This radical move reflects more than authorial repositioning. The novel voice of Aratus harnessed the heavens as a cosmological realm populated by mythopoetic heroes and celestial wonders replete with signposts for knowledgeable stargazers to discern. The abundance promised to farmers who augured well the agrarian signs, and the safe journeys vouchsafed to sailors who navigated auspicious times for travel, had been established by none other than attentive Zeus. The stars and their constellations were a road map to Greek or Frankish survival, and arguably even to individual success, according to Aratus’s proem:

Filled with Zeus are all highways and all meeting-places of people, filled are the sea and harbours; in all circumstances we are all dependent on Zeus. For we are also his children, and he benignly gives helpful signs to men, and rouses people to work, reminding them of their livelihood, tells when the soil is best for oxen and mattocks, and tells when the seasons are right both for planting trees and for sowing every kind of seed. For it was Zeus himself who fixed the signs in the sky, making them into distinct constellations, and organized stars for the year to give the most clearly defined signs of the seasonal round to men, so that everything may grow without fail.16

It is interesting that the providential role of divine oversight in the opening verses of Aratus’s Greco-Macedonian Phaenomena (or proem doubling as a panegyric to Zeus) also provides a pagan foil to a kindred idea of Christ the Good Shepherd that was appropriated by the early Christian church. The later Latin derivatives of the Aratean textual traditions, culminating with the De ordine in the Handbook of 809, attest to this development, which further enhanced the individualistic turn in Aratus’s transformation of the earlier information about the stars reported by Eudoxus, his fourth-century predecessor (fl. 368–365 B.C.E.). Other notable deviations from the lost text of Eudoxus include Aratus’s effort to align the advent of the constellations appropriate to seasonal zodiac signs with their respective positions on the solstitial or equinoctial colures.17

In part 2 below, chapter 3 examines the stylistic concerns of importance for a revisionist history of Carolingian painting in Metz, while chapter 4 details the significant transformations of long-standing Aratean traditions in the service of a Carolingian scientific soteriology. (Students of philology rather than art history may prefer to read chapter 4 before returning here, recognizing that an alternate trajectory through the text will affect the presentation of ideas and the overarching argument of this book: namely, that Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 documents in its texts and imagery a comprehensive Carolingian effort to preserve a simulacrum of celestial order.) In the present chapter, a survey of the star pictures in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 permits an exhaustive iconographic review of the origins and nature of the forms of the zodiac and constellations that were available to ninth-century painters.

Zeus’s array of constellations, which resulted in part from the legendary catasterisms of Greek mythology, were stolen in Promethean fashion from the pagan deity and set within the minds and hearts of Frankish students of the liberal art of astronomy. The De ordine recounts in general terms the mythic heritage of the constellations and thereby announces from the outset the twin themes of the text:

Here is the order and the placement of the constellations, which were fixed in the heavens by the grouping of several stars into signs. The kinds of forms are believed to have been admitted into the heavens from some models or fables. The arrangement of the natural forms did not yield their names, but human conviction gave the numbers and names to the stars. But, in accordance with Aratus the number of stars belonging to each sign has been appointed; the description should follow according to the order, which is his own.18

Not Zeus but the pagan ancestors of eighth- and ninth-century Christians thus clustered the stars and then gave these arbitrary groupings the names by which they remain known to this day. Advancing a personal outlook, the Frankish author of the De ordine relied upon the same powers of imagination and intellect that earlier people had used to designate the constellations. In so doing, the author of the De ordine followed Aratus’s lead, but in keeping with standard interpretations of the Frankish renewal: the individual early medieval Christian’s position within the cosmos (and the concomitant placement of his microcosmic soul) required a novel celebration of Aratean tradition. The Franks reoriented their understanding of the heavens and pointed Carolingian astronomical study in a joint scholarly and spiritual direction, one that permitted revision of classical narratives that had come down via lines of textual transmission discussed here and in chapter 4. The emphasis on the individual person’s observation of the heavens, inherited from Aratus and coupled with a sincere desire to reinterpret tradition to fit the needs of a new ruler and polity, were therefore parlayed into an unexpected Christocentric, soteriological focus as a driving motivation for the Carolingian study of astronomy and the stars. As explained in the introduction and argued in this chapter, the images of the constellations themselves attest to the scientific sacralization of antiquity and make possible the Frankish scientific soteriology witnessed by novel presentations of the constellations.

Given these preliminary considerations, it is not surprising that a learned translator of astronomical texts from Corbie adopted and adapted the order of the star pictures belonging to Aratean textual traditions for his Christian presentation of the constellations. This supplied a meaningful structure for the De ordine, transported by Adalhard of Corbie to the Aachen synod of 809. In all Aratean texts, the standard way to adduce the constellations, including the zodiac, was to begin with the celestial hemisphere north of the ecliptic and continue with those constellations found south of the ecliptic.19 Hence the depictions of the constellations in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 will be described in the order in which they appear, adhering to and revealing the standard text of the De ordine. This ordered presentation of the constellations recurs in other texts derived from the Aratean Phaenomena.20 Since there is such a high degree of standardization in the sequence of the cycle, the idiosyncrasies in discrete pictorial programs and alterations associated with various textual recensions become significant. Before returning to a discussion of Adalhard, it is useful to review precisely how he and others envisioned the structure of the celestial sphere.

The ecliptic is the oblique that circles the celestial sphere on which are permanently situated the fixed stars, composing the constellations. The entire celestial sphere rotates daily in a clockwise direction about a stationary earth. This line receives its name because it defines the path of the sun throughout the course of the year. Since all planets—including the moon and sun, according to the Ptolemaic model of the solar system—revolve about the earth in a counterclockwise direction, the only place the sun, moon, and earth can overlap is on the ecliptic, at the center of the geometrically distributed twelve-part zodiac belt, causing eclipses.21

According to a Carolingian understanding of Plinian and classical astronomy, the zodiac belt extends 6 degrees north and south of the ecliptic, defining a 12-degree diagonal swath of space through which the planets move latitudinally, according to their inclination, relative to the ecliptic. The equator defines the central circumference of the earth and is complemented by the so-called celestial equator exactly parallel to it.22 The parallel tropics of Cancer to the north and Capricorn to the south of the equator identify zones of roughly 23.5 degrees of geographic latitudinal space, respectively. The oblique ecliptic intersects the tropic of Capricorn at its southernmost point in the region once occupied by the constellation Capricorn, whereas it intersects the tropic of Cancer in the former region of the zodiac constellation Cancer at its northernmost point. This also explains the origin of the tropics’ names.23 Because of the phenomenon of precession, or the perpetual shift of all constellations on the celestial sphere from west to east (i.e., counterclockwise) over time, the geometric 30-degree sections of the ecliptic defined as the signs of the zodiac do not align perfectly with the constellations that bear their names and through which the sun passes annually. In other words, stars from the constellation Pisces are actually located within the spatial zone identified by the geometric zodiac sign of Aries; Aries, the constellation, has entered Taurus’s territory; and so forth.24

Again, according to the geocentric model of the universe, the fixed and wandering stars (planets) rotate around the earth. There are two conflicting motions, which typically cause great confusion for those trying to understand a medieval view of the heavens. On the one hand, the sun and all planets make their way through the zodiac signs along a counterclockwise trajectory (ignoring for the moment the phenomenon of apparent planetary retrograde motion discussed in chapter 3) that follows the order on the diagram “The Apsides of the Planetary Orbits Within the Zodiac” in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 (fol. 65v; see fig. 5). Thus we see Aries at 9:00, designating the beginning of solar springtime renewal, followed by Taurus, Gemini, Cancer, Leo, Virgo, Libra, Scorpio, Sagittarius, Capricorn, Aquarius, Pisces. Simultaneously, every heavenly body within the geocentric cosmological model, including a fortiori the celestial sphere of the fixed stars, rotates about the stable earth once daily in an apparently alternate clockwise motion.25 These two aspects of the medieval celestial model derived from Ptolemy permit the daily passage of the sun and moon as well as the seasonal shifts linked to the liturgical calendars, regulating lives on earth through their rapport with the celestial bodies surrounding them on all sides.26 In the words of Aratus, “The numerous stars, scattered in different directions, sweep all alike across the sky every day continuously for ever. The axis, however, does not move even slightly from its place, but just stays for ever fixed, holds the earth in the centre evenly balanced, and rotates the sky itself.”27

Hubert Le Bourdellès has emphasized the significance of Adalhard of Corbie’s involvement in the synod of 809. Adalhard was, as noted in the introduction, named in the report that followed the convocation of the computistical subgroup that assessed the state of the knowledge of computus during the synod of 809.28 It is highly likely that Adalhard brought two vital records of Frankish interest in astronomy with him to the Aachen synod. Those two new Carolingian creations from Corbie became the key illustrated components of book V in the Handbook of 809. Le Bourdellès has fully identified the textual sources for these two records, and this information is key to the story of the creation of Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 undertaken here. The Excerptum (text V.1) supplied an abstract, as it were, of the version of the Aratus Latinus known as the Revised Aratus. The Aratus Latinus was a translation into Latin from the ancient Greek poem described here, the Phaenomena of Aratus. The earlier translation probably took place at Corbie around 735 and then provided the foundation for the Revised Aratus, which is also likely to have been made in Corbie, around 790.29 The most important example of the Revised Aratus is the third-generation copy from Corbie presently located in Paris (Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 12957; hereafter the Paris Aratus). Created in the ninth century (probably ca. 810), this copy of the Revised Aratus includes a set of miniatures (fig. 35). The line drawings suggest to Le Bourdellès that both the original copy of the Aratus Latinus translation from Greek into Latin and the lost original copy of the Revised Aratus itself were illustrated with Aratean star pictures.30

These are contentious points, although Le Bourdellès is probably accurate in his assessment. An explanation of the reasons he is apt to be correct is essential for an understanding of the origin of the star pictures found in the Handbook of 809, and a fortiori for those in Drogo’s copy. In addition, for this art history of Carolingian astronomical manuscripts, it is equally important to assess whether lost, hypothetical cycles of star pictures included drawings alone or miniatures as well. It is highly likely that there was an originally illustrated copy of the Revised Aratus made in Corbie. The evidence for an originally illustrated Aratus Latinus is sketchier. There were no illustrations in the early copy of the type A version of the astronomical encyclopedia (according to Borst’s nomenclature) discussed in chapter 1, the Verona compilation.31 In the late eighth century, medieval scribes therefore did not consider astronomical compilations in need of artistic illustration. In fact, some later copies of the Aratus Latinus lack illustrations (e.g., Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Ms lat. 7886, ca. 850–75; Brussels, MS 10698, twelfth century). But other copies of the Aratus Latinus were probably illustrated (see fig. 7) with detailed line drawings depicting the stars, like those accompanying the portion of the Basel Scholia devoted to the Germanicus translation with scholia.32

FIGURE 35

Celestial globe. Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, MS lat. 12957, fol. 63v. Photo: BnF.

In any case, Aratean manuscripts were not always illustrated. In the case of the Handbook of 809, however, miniatures constituted an integral component of the early luxury copies of the handbook. The ninth-century pictorial cycle in Paris could have been a later addition to the lost original copy of the text, although this is unlikely. The introduction of pictures into the Revised Aratus could have taken place during the manufacture of the hypothetical intermediary copy, postulated by Le Bourdellès, that probably supplied the immediate precursor for the copy from Paris and another presently in Cologne (Cologne, Dombibliothek, MS 83-II, hereafter the Cologne Aratus; fig. 8).33

The Cologne Aratus includes a date from the incarnation of the Lord of 798 on folio 14v and was probably completed on art-historical grounds in 805. Hildebald, who was archbishop of Cologne (before 787–818) and archchaplain to Charlemagne, compiled the manuscript.34 Charlemagne decreed that clerics should undertake the mastery of the computus with the Capitulary of Diedenhofen (Thionville) in 805. The coincidence between the completion date of work on the Cologne manuscript (805) and the capitulary has led Anton von Euw to hypothesize a direct connection between Charlemagne’s desire for an astronomical-computistical-pedagogical handbook and Cologne.35 In other words, the Cologne copy of the Revised Aratus was an early attempt to create an astronomical and computistical teaching manual before the Handbook of 809.

Two observations about the Cologne Aratus are noteworthy for the history of star pictures during the Carolingian era. First, the completed miniatures in Cologne, finished by 805, are truly painterly, such as the image of Hercules and the serpent on folio 156v (fig. 8). By comparison, the drawings in the Paris copy of the Revised Aratus supply linear contours (fig. 35). A parallel disparity exists between the paintings in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 (plate 2) and the linear forms belonging to a set of suitably related copies of the Handbook of 809 that justify their assignment to a specific recension: Monza f–9/176 (figs. 36–37) and Vat. lat. 645 (fig. 38). Painted miniatures were actually the exception rather than the rule among the Carolingian manuscripts with star pictures. The inclusion of painted miniatures, as opposed to linear contour drawings, was clearly intended to convey the superiority and excellence of a de luxe manuscript such as Drogo’s princely copy. Astronomical-computistical compilations of great refinement, replete with painterly miniatures, fulfilled more than a pedagogical purpose. They were also expressions of a patron’s power and influence. Given this conclusion, there is little doubt that the original copy of the handbook compiled in Aachen under the direction of Adalhard of Corbie also included a lavishly painted cycle of miniatures. It was made for Charlemagne.

Second, the Cologne and Madrid manuscripts were both made for patrons who were at one time archchaplains of the Carolingian kingdom, as discussed briefly in chapter 1. Hildebald of Cologne ascended to the archchaplaincy after the death of Angilram of Metz in 791.36 Bishop Drogo served both Louis the Pious (after 834) and Lothar I (after 842) as archchaplain, too.37 Since Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 was made around 830, it is reasonable to see in the painterly production of the miniatures an effort to surpass the quality of painting in Hildebald’s proposal for a handbook.

In any case, the pictorial cycles of the Paris Aratus38 (fig. 35) and Cologne Aratus (fig. 8) are similar enough to warrant the suggestion that their predecessor influenced the order and the arrangement of the pictorial cycle in these manuscripts. The pictorial program in these two manuscripts is also relatively similar to the various copies of the Revised Aratus belonging to the second branch of the bifurcated stemma provided by Le Bourdellès. This further supports his contention that the original copy of the Revised Aratus was indeed illustrated. For example, one of the copies from the other branch of Revised Aratus manuscripts is Saint-Gall, Codex 902 of the mid-ninth century (Stiftsbibliothek Sankt-Gallen, Cod. 902, hereafter Saint-Gall 902; figs. 39–40). Saint-Gall 902 includes the illustrated portion of the text referred to as the Recensio interpolata in earlier literature.39 The image of Aries on page 90 (fig. 39) resembles the basic linear form of the painted image in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 (plate 9), but in reverse.

FIGURE 36

Gemini and Cancer. Monza, Biblioteca Capitolare, f-9/176, fol. 63v. Photo © Biblioteca Capitolare del Duomo di Monza.

FIGURE 37

Sagittarius, Aquila, and Delphinus. Monza, Biblioteca Capitolare, f-9/176, fol. 67r. Photo © Biblioteca Capitolare del Duomo di Monza.

FIGURE 38

Gemini and Cancer. Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. lat. 645, fol. 58v. Photo © 2017 Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana. Reproduced by permission of Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, with all rights reserved.

This iconographic similarity with manifest variety is a standard phenomenon found throughout the individual Carolingian manuscripts containing star pictures. The similarities derive from the long-standing Aratean precursors under discussion here, but the individual differences in specific codices permit additional meanings beyond straightforward classical references. These novel insights are the true legacy of Carolingian book painters to pictorial art. That does not compromise the significance of the Aratean texts transmitted for posterity. On the contrary, along two intrinsically intertwined trajectories, the value of Carolingian scribes to the accurate preservation of texts can be celebrated equally with the interpretative efforts of Frankish painters who built visually on the work of their predecessors and turned tradition into new ninth-century erudition, replete with the awe and wonder the heavens can induce.

The uniformities displayed by depictions of the constellations in the Revised Aratus manuscripts supply the best reason to argue backward for an originally and similarly illustrated Aratus Latinus. For example, the image of Arcturus Maior (The Great Bear) on page 82 of Saint-Gall 902 resembles the basic linear form of the related images in the Paris Aratus (fol. 64r) and Cologne Aratus (fol. 155r). Moreover, in all three cases, the quadruped faces to the left. Naturally, the general forms of the zodiac and constellations can be traced back to Hellenistic precursors. According to Mechthild Haffner, the finalization of the relatively standard pictorial program of the illustrated copies of the Germanicus translation of the Phaenomena, which influenced the order and form of the pictures in the Aratus Latinus and the Revised Aratus, took place in the late third century. These images were attached originally to a hypothetical Greek copy of the Phaenomena with scholia, referred to in the scholarly literature as Φ.

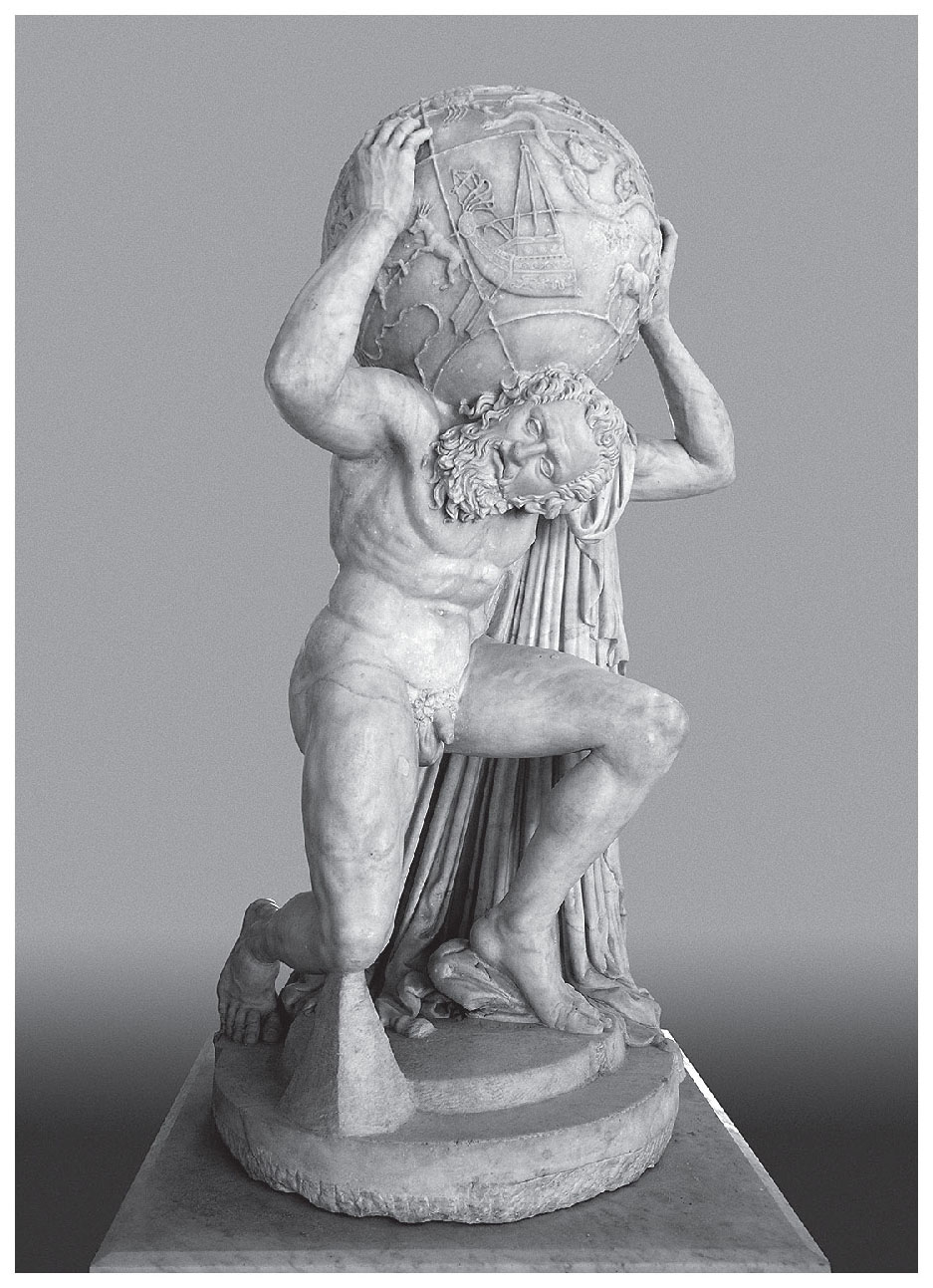

Haffner has noted that certain miniatures in Aratean manuscripts can only be explained by the scholia introduced into the textual redactions. This suggests that the iconography of the star pictures changed over time or that the pictures were added to the text after its composition (at a potentially much later date). For example, a kneeling Hercules only makes sense in the context of the conflict between the hero and the serpent, described in scholia, which later influenced the creation of the Basel Scholia supplementing the Germanicus translation into Latin of the Aratus poem (fig. 7). In other words, Haffner believed that the definitive set of illustrations that influenced medieval astronomical and astrological cycles of pictures was added to the Aratus tradition roughly five centuries after the composition of the original poem by Aratus, and the textual analyses of Le Bourdellès have corroborated this result.

Under this interpretation, the advent of the codex roughly coincided with the creation of a series of illustrations for the Aratean manuscripts—a series that would later become comprehensive. In the third century, the images adhered to a pictorial logic appropriate for a rotulus in Alexandria. During the transition period from the rotulus to the codex, Haffner has argued, there were linear star pictures without frames accompanying a Greek edition of the Phaenomena with scholia. Interestingly, many of the putative earlier examples of the constellations tended to display the dorsal sides of the constellations, as though they were viewed outside the ring of fixed stars on an ideal celestial globe. Haffner’s ingenious solution to the problem of the transmission of the Aratean text and star pictures was to postulate a new Latin translation of the Phaenomena in the late third or early fourth century. This edition relied upon the Germanicus translation for a model, while the translators also addressed the Greek scholia, thereby creating the accompanying Latin scholia, namely, the Basel Scholia. The miniatures accompanying the copies of the Germanicus translation from around that period onward supposedly displayed true codex illustrations, with blue fields and red frames (fig. 21), recalling the pictures in the Carolingian ninth-century Leiden Aratea.40

Colin Roberts and T. C. Skeat have identified the late third and early fourth century as the point at which bound books generally replaced rotuli as the vehicle of choice for the transfer of written information.41 This finding buttresses Haffner’s hypothesis. Here, however, in assessing the origins of the astronomical miniatures in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809, we must recognize the plausibility of an originally illustrated Revised Aratus. That pictorial cycle probably harked back to an original program created in the third century in Alexandria for the Greek edition of the Aratea with scholia. That edition, as Le Bourdellès proposed, probably provided the model for the pictures introduced into the Aratus Latinus and then into the Revised Aratus, recognizing that with every copy there were opportunities for creative aesthetic decisions.42

FIGURE 39

Aries, Deltoton, and Pisces (Aquilonalis and Australis). Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen, Cod. Sang. 902, page 90. Photo: Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen.

Like Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809, the Cologne Aratus included miniatures in open fields between single-column text blocks. These de luxe painted astronomical manuscripts preferred to return to the more ancient graphic style of unframed images, which was actually associated with a rotulus. On the one hand, these aspects of the pictorial cycles in early medieval illustrated astronomical manuscripts are emblematic of beliefs about early manuscript illustration espoused by Kurt Weitzmann.43 On the other hand, the pictures in these two codices have received uncommon emphasis. In the Paris Aratus (fig. 35) and Saint-Gall 902 (fig. 40), the linear renderings of the constellations have been squeezed into the available allotted spaces, pushing up against the margins. The linear forms seem to be inconsequential diversions from the dominant text blocks in those manuscripts. Yet not only did the de luxe copies of ninth-century astronomical treatises receive painted miniatures, but those miniatures were also placed in free-standing, unframed open spaces, highlighting the independence and artistic refinement of the forms. It is important to note here that the highly developed tinted drawings of the sister manuscript to the Saint-Gall 902 (fig. 40), the Saint-Gall Cod. 250 (Stiftsbibliothek Sankt-Gallen), were also set apart, according to the design strategy for an exceptionally refined cycle of miniatures. The monastic draughtsmen inserted their highly finished drawings into Saint-Gall 250 in open spaces between single text columns in the last quarter of the ninth century, following the procedure for a more luxurious copy of an illustrated astronomical text.44 The one-column format was in no way reserved for the painted manuscripts alone, although the presence of paintings and a single-column format in the Madrid and Cologne manuscripts clearly conveys their exceptional refinement and splendor. This actually opposes one tenet of Weitzmann’s history of early manuscript illustration. Weitzmann has argued for a steady progression from early cycles of illustration in scrolls to the emancipation of gilded images, which resulted in framed manuscript illuminations.45 Notably, early medieval artists could accentuate the value of their miniatures without the use of frames.

In summary, it is highly likely that a pictorial program enlivened the original edition of the Revised Aratus, and that this pictorial cycle had a significant impact on the development of future star pictures. The Excerptum from the Handbook of 809 (V.1) was not illustrated, but it was the prelude to the text that included the illustrations, namely, the De ordine (V.2). For this reason, it is highly significant that the Excerptum was derived from the Revised Aratus, as argued by Le Bourdellès, and that the Revised Aratus originally included a set of star pictures like those in the Cologne Aratus.

Le Bourdellès also identified the second text from book V of the Handbook of 809 as an original contribution, which Adalhard brought from Corbie to the synod meeting in 809. The text provided a summary of the Basel Scholia.46 The latter name derived from the scholia included within a manuscript likewise containing the fragmentary copy of the Aratus Latinus (and not Revised Aratus) attached to an edition of the Germanicus translation in Basel, as mentioned above. It is known that the scholia in Latin could not have been added to any putative version of the Aratus poem that arose before the imperial period of classical Rome, since the scholia included references to the writings of Publius Nigidius Figulus (active ca. 98–45 B.C.E.).47 The Latin scholia were translated ca. 300 C.E. from the commentaries to the lost Alexandrian redaction of the Phaenomena by Aratus, as discussed already. Le Bourdellès followed J. Martin when he argued that the hypothetical Alexandrian text combined the Aratus poem with an introductory text summarizing the ideas of Eratosthenes (ca. 276–194 B.C.E.) on terrestrial or celestial globes. In any case, the commentaries had been added to the Germanicus translation by the fourth century, as Le Bourdellès noted, because the Christian exegete from Trier, Lactantius (240–ca. 320 C.E.), alluded to the commentary in his Divinae Institutiones (I.11).48 All of Le Bourdellès’ findings, therefore, corroborate the positions advanced by Haffner.

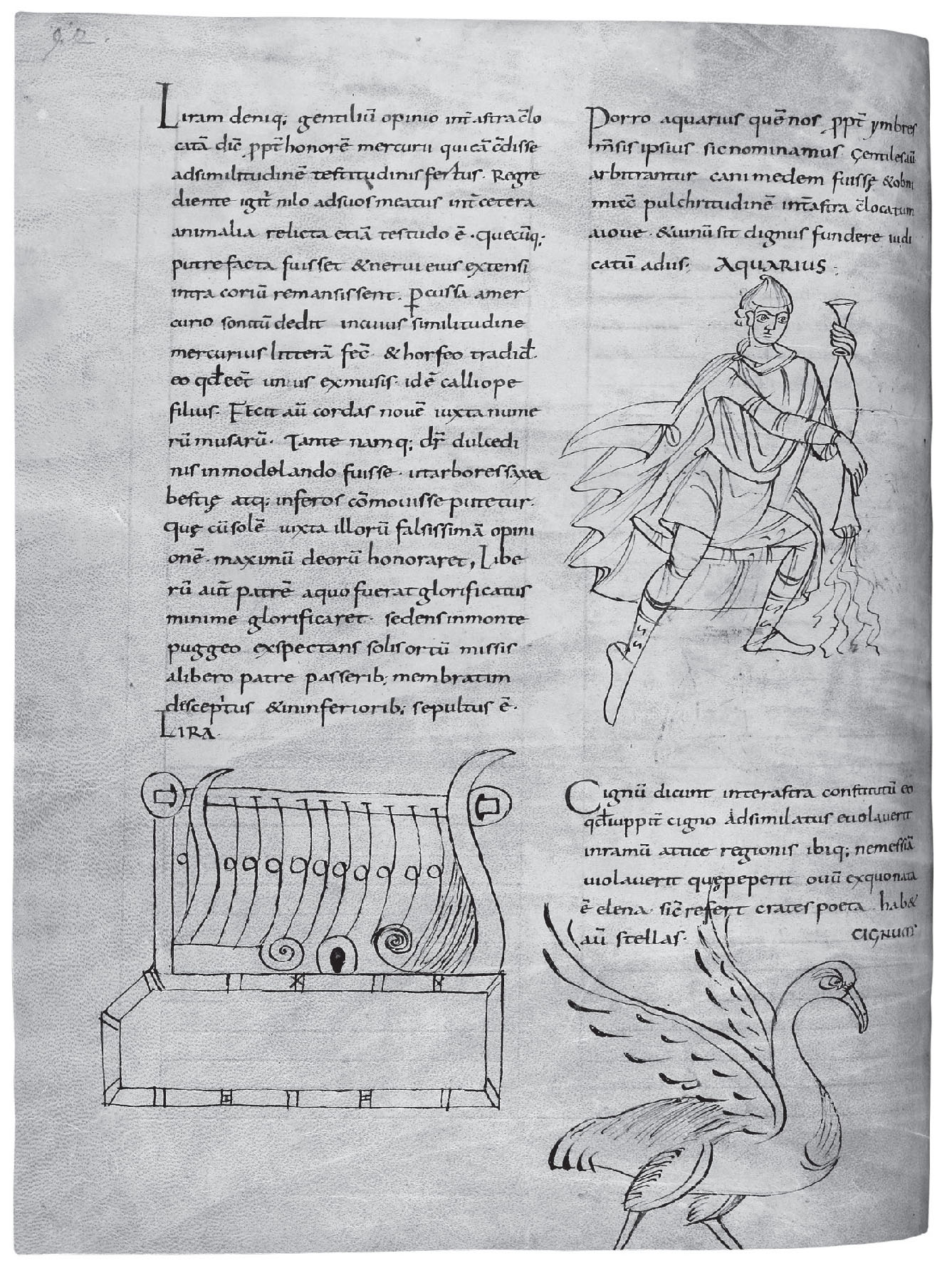

FIGURE 40

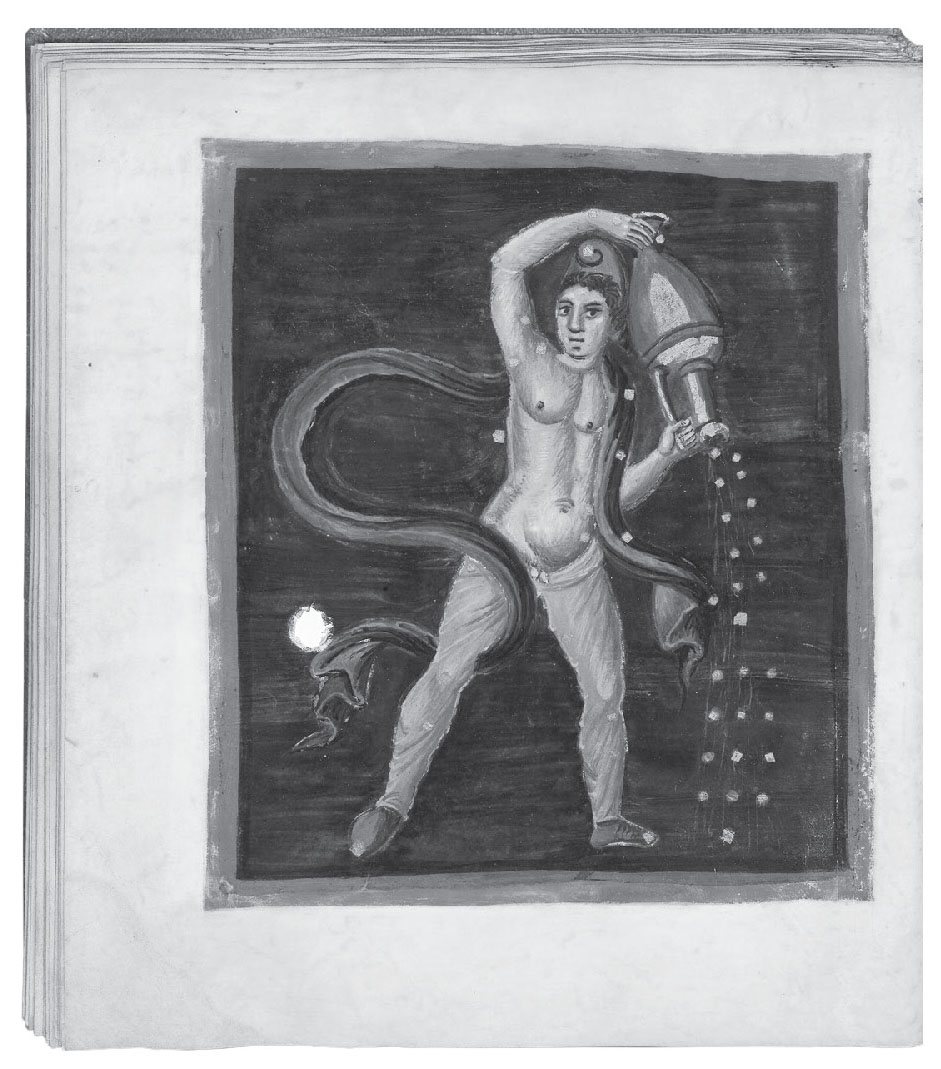

Lyra, Aquarius, and Cygnus. Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen, Cod. Sang. 902, page 92. Photo: Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen.

In the third-century Alexandrian corpus, the Aratean descriptions of the constellations also included mythological tales about the constellations and star pictures. These supplemental mythological texts provided an account of the fictional reasons for which each of the constellations appeared in the heavens as the handiwork of the gods. Whenever a person, such as Hercules/Engonasin, or a creature, such as Cancer the Crab, was magically preserved for posterity by the introduction of a constellation in its form and honor, a catasterism had taken place. These catasterisms, described in a text derived from Eratosthenes, also catalogued the stars visible within a depiction of a constellation. The Latin translation of the Catasterisms from the Alexandrian compilation provided a supplemental list of the stars in the heavens added to the Germanicus translation of the Aratean Phaenomena. These insertions into the Germanicus text adduced mythological references and a list of stars, one constellation at a time. This complement constituted most precisely the so-called Scholia Basileensia.49 The descriptions formed the basis of the new Carolingian catalogue of the stars within the constellations, the De ordine, albeit without the mythological references.

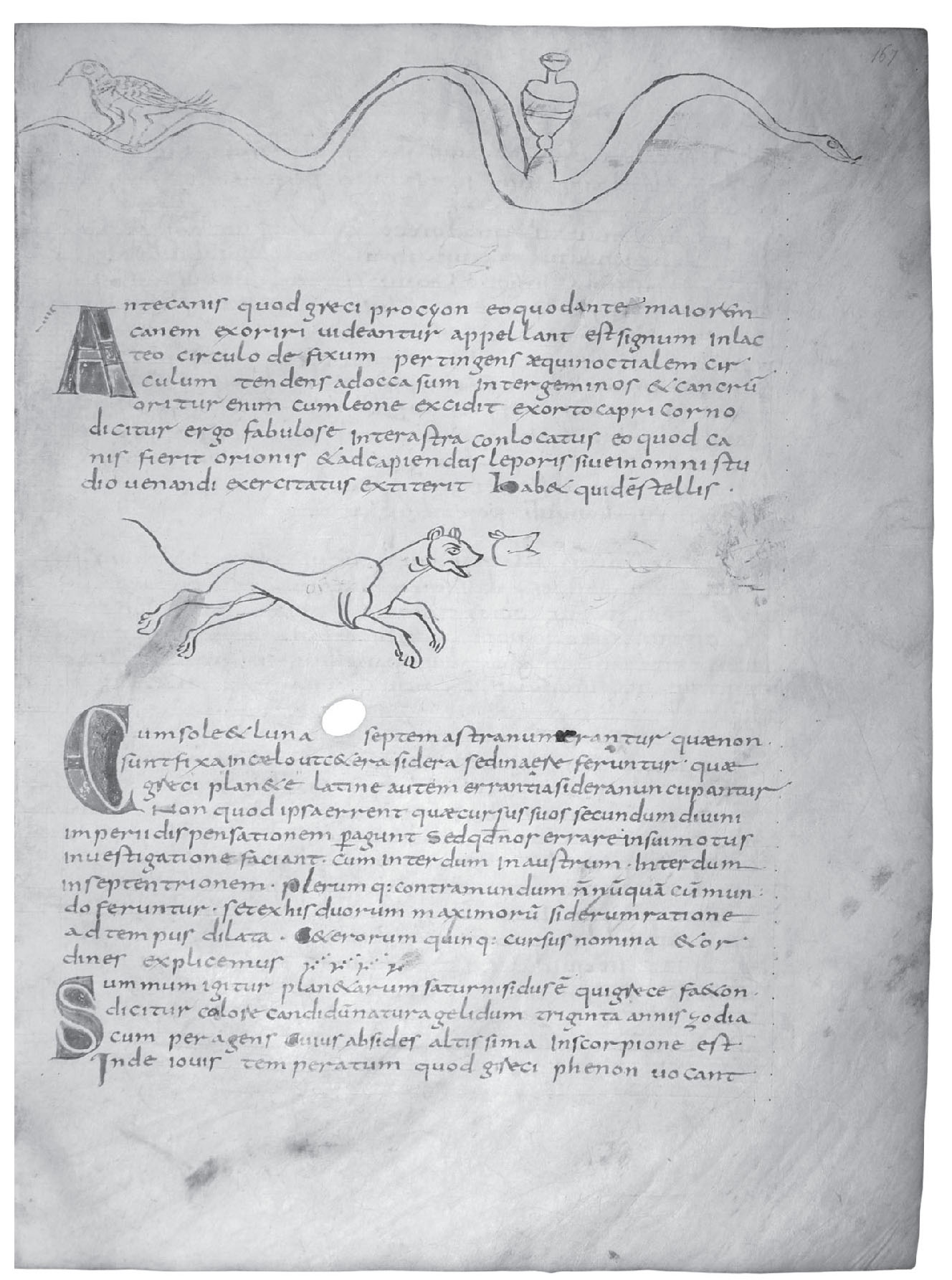

In 1898, Georg Thiele had already recognized the link between the group of manuscripts containing the De ordine and the Catasterisms in the most important early contribution to the study of medieval astronomical illustration, the Antike Himmelsbilder. Thiele labeled this set of manuscripts the “Phillippicus Class,” because there is another Carolingian copy of the De ordine closely related to Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 in Berlin (Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, MS Phill. 1832; hereafter the Berlin Ordine). Thiele linked, for example, some of the pictures with curious iconographies, such as the satyr form of Sagittarius (fig. 41), to an earlier book of Catasterisms on these grounds.50 Whenever possible, the text of the De ordine and the imagery in the Carolingian Handbook of 809 emphasized meteorological details or made references to antiquarian forms of the constellations associated with zodiac cycles and celestial globes. These decisions were motivated by a zealous desire for scientific accuracy and an unshakable, fundamental belief in the intellectual sophistication of classical learning throughout the Frankish lands. The Franks could only achieve the scientific sacralization of the zodiac and the Greco-Roman history of the constellations by first fully immersing themselves in the historiographic tradition.

FIGURE 41

Lyra, Cygnus, Aquarius, Capricorn, Sagittarius, and Aquila. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Hs. Phillipps 1832, fol. 84v. Photo: bpk, Berlin / Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin / Art Resource, New York.

Christian Pictures of Pagan Constellations North of the Ecliptic

In Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809, forty-two descriptions51 of the constellations in single-column format are each followed by a free-standing Carolingian miniature. Drogo’s personal reading reenacted the passage of the celestial bodies, meditating upon the information about the stars presented in the trimmed-down, palatable Christian text, the De ordine. The paintings document the Carolingian reaction to painterly styles of modeled forms, which Frankish viewers could access in late antique mosaics, extant frescoes, and manuscripts such as the Calendar of 354, known to have existed in a Carolingian copy.52 The Carolingian star pictures, along with their linear style of execution, perhaps derive in part from such models, or from a lost late antique art of celestial globe production. Carolingian artists are known to have employed a polycyclic strategy of image selection when producing new pictorial cycles for codices that were intended to relay conceits and concepts linked to science and the liberal arts. The roots of the star pictures are nevertheless unequivocally linked to the history and textual transmission of the illustrated Aratean texts just discussed.53 It is important to underline here exactly what is meant by an innovative or original pictorial cycle during the Carolingian period, especially vis-à-vis star pictures.

To make a general point, it is impossible to label anything even vaguely reminiscent of a crab a thoroughly original depiction of the zodiac sign Cancer. That is precisely because the form belongs to a standard type. The standardization of the form of the sign had been defined by human observation, in agreement with how people had long since clustered the stars in the sky into recognizable patterns. By the ninth century, the form of the constellation Cancer had been fixed for all of human time. The selection of the crab as an appropriate form for Cancer was no longer an interpretative artistic decision in the ninth century; its use provided an accurate scientific report of the facts of the matter. It would be just as meaningless to evaluate a chemistry student’s sculptural creativity with respect to her model of a water molecule, rendered accurately with three colored wooden balls and floppy springs. Mutatis mutandis, the same applies to contemporary digital imaging software, rendering discrete components of coded molecular structures more readily apparent and discernible than the blades of grass on the lawn beyond one’s window. In all these cases, the presentation conforms to an accurate model grounded in scientific observation and theory. Various star pictures become significant for the history of art when they are rendered with powerful individuality. The way in which the Carolingian artists in Metz represented the ninth-century images of the constellations in Drogo’s personal copy of the Handbook of 809 (Madrid 3307) turned the manuscript into a superior creative achievement. It is possible to evaluate Carolingian star pictures for their relative adherence to the prototypes derived from Aratean traditions and ancient star globes. It is equally possible to celebrate the Carolingian star pictures in Madrid 3307 for their innovative painterly forms of the constellations.

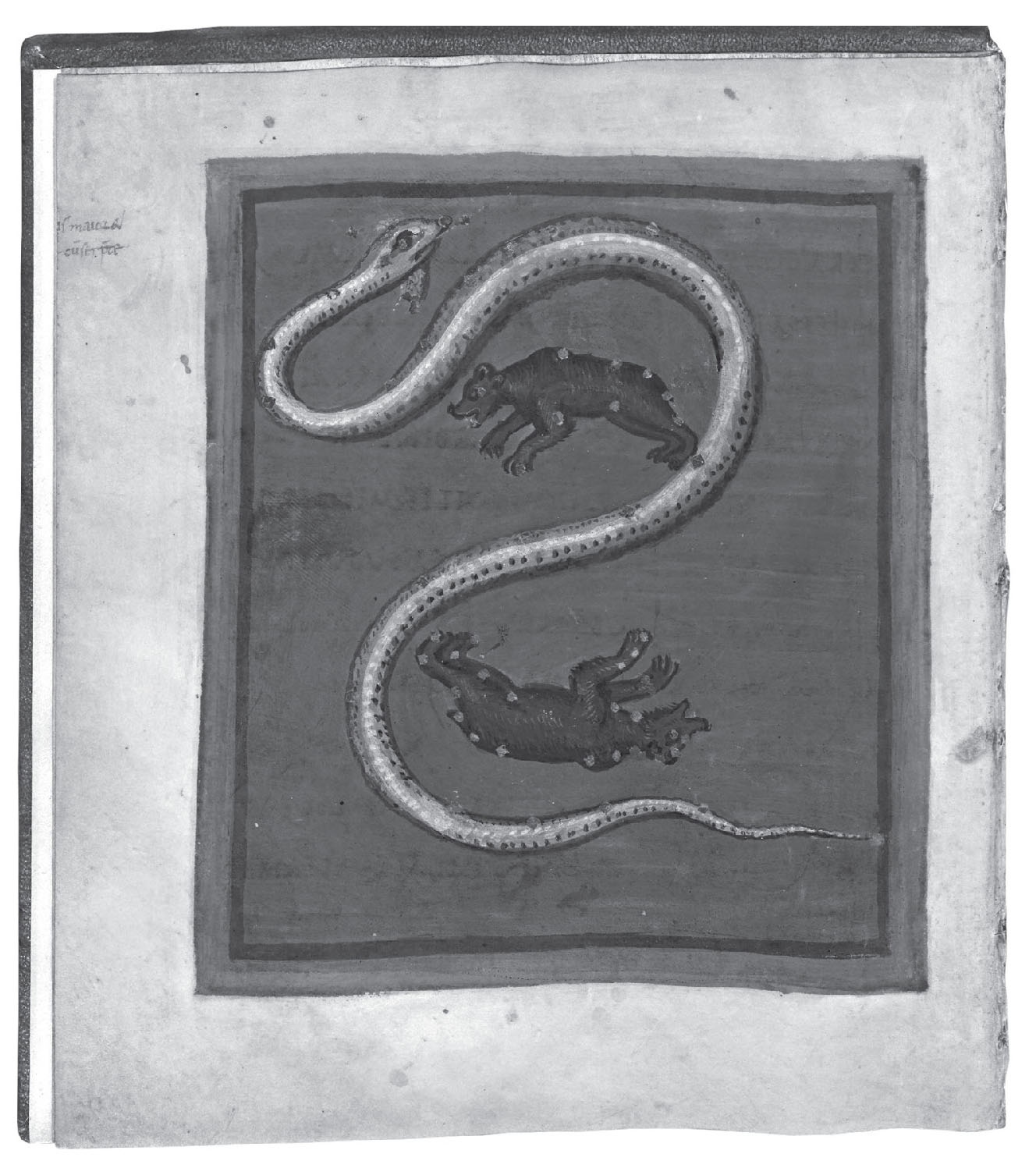

Beginning with the northern hemisphere, at the north pole, the serpent, Serpens, intertwines with the forms of the two bears: Ursa Major, otherwise known as Haelice or Arcturus Maior, and Ursa Minor, also known as Cinosura or Arcturus Minor. The forms of the miniatures in Drogo’s copy of the handbook derive in part from those found in the Aratean manuscripts, which were consulted in the composition of the De ordine in Corbie. The similarities and dissimilarities among the Carolingian star pictures become readily apparent when we compare the individual depictions of the bears and serpent (plate 1) with the single image of the trio found on folio 3v in the celebrated Leiden Aratea, which belongs to a set of manuscripts associated with the court of Louis the Pious (fig. 42).54

The text begins with a description of the stars in the Great Bear: “Haelice, the Great Bear, has seven stars in its head. There is one star in each visible shoulder, one in the arm, one in the chest, two bright stars altogether in the front paw, one bright one in the tail, one bright one in the belly, two in the back leg, two in the rear paw, and three more in the tail. This makes a total of twenty-two stars.”55 Immediately thereafter, an artist painted the Great Bear (plate 1). The descriptions of the constellations in Drogo’s book, derived in part from the descriptions in the Catasterisms attributed to Eratosthenes, had been stripped of their original mythological content.56 In the text of the De ordine prepared for the Handbook of 809, the paramount concern was the composition of a text that would fulfill Charlemagne’s mandate for a pedagogical tool. Adalhard of Corbie was probably personally responsible for the removal of this mythological content from the Basel Scholia to rid the astronomical information of pagan associations.57 This was perhaps the most important innovation made by the Carolingian author(s) of the De ordine, and it continued a practice that had already played an important role in the development of the Revised Aratus.

As Le Bourdellès has argued, the new Latin edition of the Aratean text from the late eighth century provided an ideal opportunity to render it up-to-date with the latest in Christian education—a goal that was in complete accord with widespread Carolingian strategies for scientific sacralization. Classical ideas in the Revised Aratus were intentionally juxtaposed with information culled from Isidore, and inspiration for at least one passage even harks back to the recently deceased Venerable Bede.58 The suppression of the mythological material emphasized the condemnation of paganism by the prelates who had attended the synod of 809. The refusal to include or to examine the secular content traditionally associated with the constellations also underscored their rejection of late classical Roman paganism and the indigenous Germanic religious practices with which such beliefs intertwined in the ninth century.59

FIGURE 42

Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, and Draco from the Leiden Aratea, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit, MS Voss. lat. Q. 79, fol. 3v. Photo courtesy of Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden.

FIGURE 43

Arcturus Minor / Ursa Minor. Cologne, Erzbisch. Diözesan- und Dombibliothek, Cod. 83-II, fol. 155v. Photo courtesy of Erzbisch. Diözesan- und Dombibliothek.

Nevertheless, it is equally important to underscore that this Christian revisionist interpretative bent likewise permeated the artistic portrayals of the constellations in Drogo’s book.60 For this reason, the requisite classical references are included in the discussion that follows, primarily to elucidate the areas in which Christian artists from Metz foisted an eighth- and ninth-century Carolingian outlook upon their star pictures and advanced a creative pictorial vision of the heavens in their novel reinterpretations of long-standing Aratean imagery.

Intriguingly, the miniatures in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 include neither representations of the adumbrated lists of stars nor a monumental format. The scale of the handbook’s miniatures is intimate, and the artistic refinement expressed by the painterly compositions was probably intended for the purposeful and pleasurable observation of its owner. Alternatively, Drogo’s copy may have been intended to be enjoyed in small group settings by a select number of elite students, either in the bishop’s company or in that of his academic masters at the cathedral school. It is easy to see how full-page versions of the same cycle of illustrations would have better fulfilled this purpose; however, it is equally meaningful to envision the use of Drogo’s manuscript in tandem with other astronomical observational tools appropriate to the ninth century, such as a star globe or a star clock (horologium nocturnum). Indeed, without such instruments, the lack of accurate stellar displacement in the images of the constellations calls into serious question their pedagogical efficacy.61 This is, however, to confuse the Handbook of 809 with a typical field guide for stargazers. The images are not arranged or presented in the same manner. The intellectual work for students of the liberal art of astronomy was different. Careful observation and analysis of the images of the constellations in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 on site in Madrid could not confirm Dieter Blume and his colleagues’ claim that the stars were once included in the constellation pictures of Drogo’s handbook.62

The handbook fulfilled Charlemagne’s pedagogical desire for a treatise on astronomy and computistics in the service of reforms within the Frankish lands. The miniatures provided basic forms that could serve as mnemotechnic teaching aids for younger stargazers.63 The lavish pictorial program presented in Drogo’s manuscript, however, surpasses in quality the linear drawings found in other copies of the Handbook of 809 (figs. 36–38). Even the simpler forms are adequately suited to fulfill their purpose as a teaching tool. The presence of such lavish miniatures in Drogo’s copy truly sets it apart as a royal commission worthy of an illegitimate son of Charlemagne. This heightened aesthetic quality gives Drogo’s book its apparent distinction as a definitive expression of the Handbook of 809. That does not mean that Drogo’s book is a more accurate reflection of any putative model; on the contrary, the profound difference in quality between Drogo’s book and the others underscores the unique nature of this creative undertaking by superior Frankish illuminators.

This lack of stars in Drogo’s handbook differs from the image cycle in the Leiden Aratea, which includes an original Germanicus Caesar translation. An additional Latin translation of the Aratea by Rufus Festus Avienus (fourth century) supplemented the text of the Germanicus translation in the Leiden manuscript.64 In the image for the Great Bear, Little Bear, and Serpent on folio 3v of the Leiden Aratea, the three constellations are clustered into one picture without true concern for the text beyond the framed border (fig. 42).65 This can be considered a general design strategy, which arranged visual information analogously to the semiotic construction of hypotactic subordinated sentences in Latin literature. This can be considered a form of visual hypotaxis, emphasizing integrated relational placement and expressing pictorial information with pristine clarity.66 In a text displaying parataxis, such as a work by Sallust, ideas are linked together in clusters without the subordination of clauses.67 In the descriptions and illustrations of the constellations from Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809, the De ordine presents a progression of text-image pairs. This sequence of syntactic text-image pairs remains subordinated to the overall structure of the De ordine, but follows the order of the constellations established by Aratus in a concatenated series of semiotic units, adduced in sequence like a paratactic history from Sallust. The imagery in Drogo’s book therefore separates the Bears from the Serpent in three discrete pictures (plate 1). The arrangement of the Bears and Serpent into three sequential text-image syntactic units emphasizes the form of each constellation and asserts the individuality of each one within the whole list of constellations in the De ordine.

This paratactic strategy was also adopted for the representations of the bears and serpent on folios 155r–156r of the Cologne Aratus (fig. 43). Comparisons of the types of images to be found in both manuscripts can tell us much about the kinds of lost late antique precursors that were harbingers of celestial understanding, relaying the classical traditions to Carolingian artists who then interpreted the ancient forms for themselves.

FIGURE 44

Hydra, Crater, and Corvus from the Leiden Aratea, Bibliotheek der Rijksuniversiteit, MS Voss. lat. Q. 79, fol. 76v. Photo courtesy of Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden.

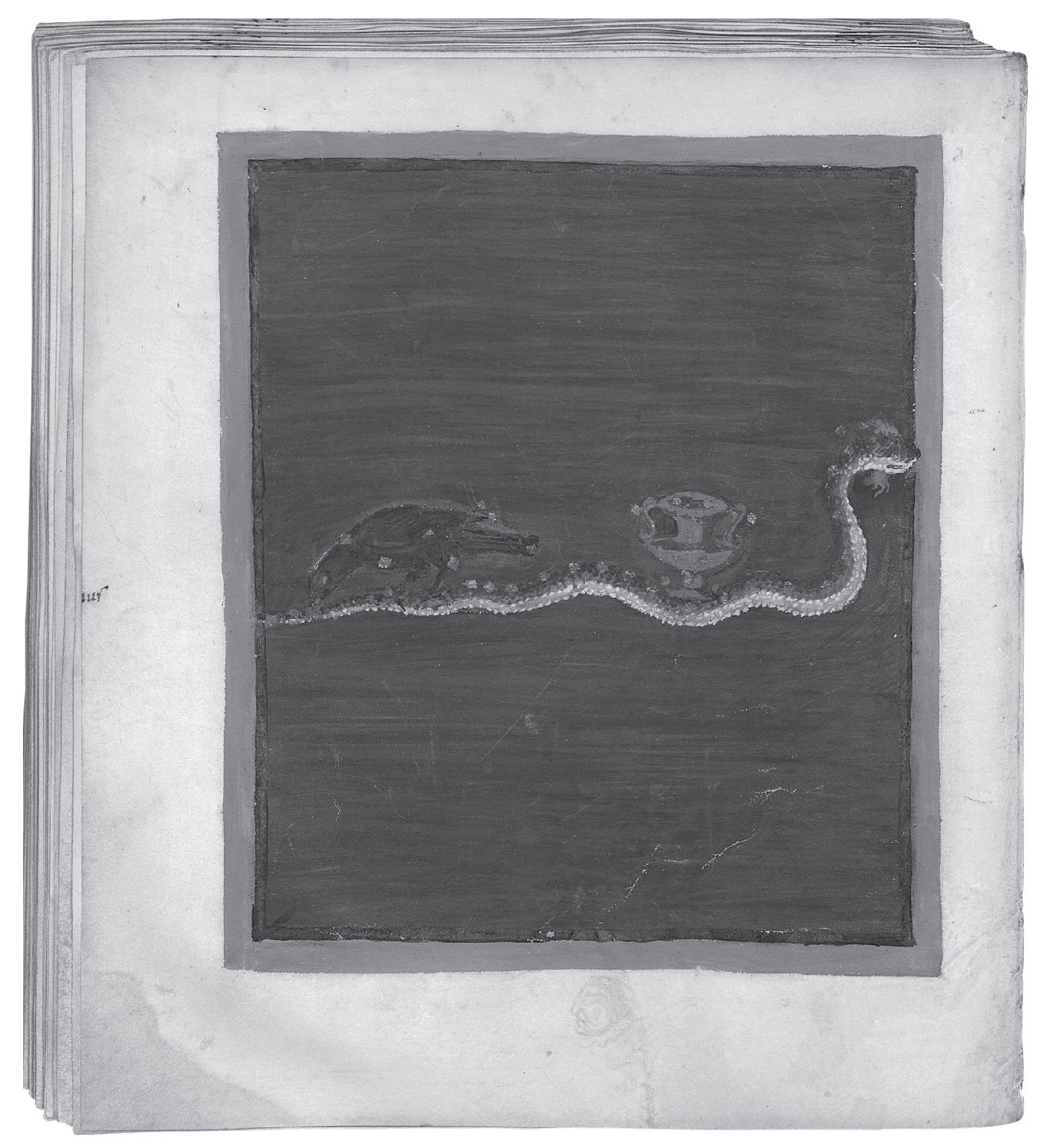

For example, three discrete images depict the Hydra, the Raven, and the Crater on folios 62r–v in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 (plates 16–17).68 The Leiden Aratea represents the three clustered together in the framed miniature on folio 76v (fig. 44), while in the Cologne Aratus, the hydra, bird, and vessel are all included within one scene at the top of folio 167r (fig. 45). The artists working in Metz preferred to emphasize the individuality of the constellations and their significance for Carolingian readers by painting three miniatures. In Drogo’s book on folio 62r, one image clusters the trio together (plate 16), according to the more standard hypotactic form included in the Leiden manuscript, followed by individual depictions of the Raven and the Crater on folio 62v (plate 17). This conforms to the semiotic strategy of compilation through juxtaposition noted in the introduction. The painters of Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 arguably sought to emphasize the coeval informational status of both text and image in the Handbook of 809. The painters in Metz pushed the design strategy of visual parataxis—experimented with in the Cologne copy of the Revised Aratus—even further. The upshot was that the pictures in Bishop Drogo’s manuscript were arguably more useful references of the forms of the individual constellations for teaching purposes than the miniatures available in the picture book, made for the court of Louis the Pious, contained in the Leiden Aratea.

The representations of the constellations of Serpens and the two bears in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 nevertheless recall the essential features of the corresponding animal forms in Leiden, taken one at a time. This was natural; the two cycles both derived from common pictorial prototypes, and of course depict the same constellations. The two bears look away from each other in opposite directions in both books. In the Leiden manuscript, they stand paw to paw across the divide delimited by the tortuous form of the serpent. In Drogo’s handbook (Madrid 3307), the bears both stand on all fours, heads forward in opposite directions. Whereas the bears in Leiden appear to leap through space in an endless, rhythmic circular chase, the two bears in Drogo’s book hover within the illusionistic space of the parchment folio. The bears in Madrid 3307 conform to the illusionistic pictorial logic appropriate to landscape painting, for they seem to stand on a missing horizon line. Medieval painters generally adopted the pictorial logic of the groundline but did not include one in most cases; in Madrid 3307, Heridanus on folio 61v may be an exception to this rule (plate 15).

More important, in Drogo’s handbook, as in the Cologne Aratus, the text block announces a spatial-semantic frontier that runs parallel to the implied horizon line on which the otherwise free-floating bears seem to stand in profile. In this way, the text not only provides the descriptions for the star catalogue but establishes a visual perimeter by blocking off the open space of the pictorial zone within which the ninth-century painters carried out their work. The fact that the paws of the Great Bear in Drogo’s book are set slightly above a line ruled in drypoint on the recto side of folio 54 provides additional visual proof that this layout was a design decision rather than an accident.

Unlike the Leiden Aratea images the miniatures in the Handbook of 809 do not have frames. The Carolingian artists who painted the original lost archetypal Handbook of 809 and the copy made for Drogo (Madrid 3307) dismantled the late antique framed images copied into the Leiden manuscript into the smaller discrete images preferred by the makers of the handbook. At the very least, the painters of Drogo’s book saw no reason to add any frames. Frankly, the preference for visual parataxis shattered the frames of the miniatures. This reduction in Madrid 3307 of the pictorial sequence into isolated units subordinated to the rhetorical structure of the De ordine was a preferred Carolingian pictorial book-making device, likewise confirmed by the Cologne copy of the Revised Aratus. The pictures in the Handbook of 809 deviate from the pictorial tradition copied by the artists who worked on the Leiden Aratea. As a result, the pictorial logic of the De ordine adheres to the twin Carolingian desires for (a) an original but simplified textual and pictorial presentation of the astronomical information appropriate to meditative study, and (b) perfect mastery in a pedagogical handbook.

FIGURE 45

Serpens/Hydra and Anticanis/Canis Minor. Cologne, Erzbisch. Diözesan- und Dombibliothek, Cod. 83-II, fol. 167r. Photo courtesy of Erzbisch. Diözesan- und Dombibliothek.

The lack of stars in the paintings of the constellations in Madrid 3307 is an odd solution, however, and calls into question the independent educational value of the miniatures. The simple text of the De ordine arguably permitted a general mental reconstruction of the placement of the stars within the painted image of the Great Bear. But such verbal descriptions could have benefited from the sort of visual representations of the stars within the constellations that are included in the Leiden Aratea. Alfred Stückelberger is the most optimistic voice about the reliability of the images in the Leiden Aratea, noting a strong correlation between the star catalogue of 1,022 fixed stars utilized by Ptolemy in the second century and the illustration of a constellation such as Sagittarius on folio 52v (fig. 21).69 This probably overstated view has been significantly revised by Elly Dekker, who instead finds the general lack of accuracy in the Leiden Aratea star pictures to derive from the joint influence of both the original Ptolemaic star catalogue and diverse literary “descriptive” traditions, including the Basel Scholia under discussion here.70

The upshot is, of course, that in both Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 and the Leiden Aratea, there is only one potentially helpful source for the localization of the stars. There is an emphasis on the semantic potential of the text in Drogo’s book, which deviates from the preference for pictorially placed stars in the Leiden Aratea. There is no reason to believe, however, that the lack of stars in the depictions of the constellations originated with Drogo’s book. Presumably, the pictorial cycle designed for the original archetypal handbook created after the synod of 809 was made the same way. Interestingly, there are also no depictions of stars in the free-standing, single-column miniatures included within the early Cologne Aratus (fig. 8). Nor are there any frames around the illustrations on the two-column text pages in the copy of the Recensio interpolata (that is, the Revised Aratus explained above) manuscript from Saint-Gall, such as the ninth-century Saint-Gall 902 (fig. 40).71 As a result, the pictures in the original, archetypal Handbook of 809 probably resembled the cycles of pictures found in manuscript copies of the Revised Aratus, not the tradition of pictures associated with the Germanicus translation in Leiden. This only serves to demonstrate that the Handbook of 809 stood at the nexus of several programmatic efforts throughout the Frankish lands: the book simplified and comprehensively conveyed astronomical and computistical acumen to the schools; the pictorial program was a coeval presentation of period science and not merely a dilettantish fancy for prelates; and the Revised Aratus and the Handbook of 809 were twin efforts at developing a serious Christian presentation of classically inspired astronomical traditions and not merely the result of sanguine reclamation projects.

The representation of Ursa Major in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 follows its textual description on folio 54v (plate 1). The bear has a stern grimace and an upturned snout, as if it is on the defensive. Its paws terminate in black lines, which reduce the form to a stylized rendition of a quadruped, seemingly with hooves. This might simply be the result of the remaining underdrawing, however. A harsh black contour supplies the basic form of the animal. Certainly, some attention was paid to ursine anatomy, such as the convincing and elevated dorsal hump. Arguably, there is a sense of overlapping perspective in the representation of the limbs of the Great Bear. In fact, the underdrawing has bled through the pigment in the right foreleg and hind leg, suggesting that the artist employed underdrawing to sketch in the animal’s general form. The painter nevertheless manipulated the basic form of the animal at a second stage, while applying the color to the parchment. This is highly informative about the practices of Carolingian painters working in Metz. Each artist first created an outline drawing before completing a miniature. Since the styles of painting and the styles of the underdrawing always display a high level of coordination, it is highly likely that each painter also provided his own preliminary contour drawing. The sketch expressed the basic form, while the finished figure communicated the mature aesthetic vision of the artist. Such a two-step process argues in favor of a sophisticated Carolingian painterly practice that had already developed by the 830s, when Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 was created.

The almost mirror image of Ursa Major, Ursa Minor (plate 1)—also known as Cinosura, according to the Epitome Catasterismorum that is derived from the now-lost star catalogue with myths contained within the original Catasterisms of Eratosthenes,72 and also as Arcturus Minor—reproduces the overall form of its bigger relative in reverse: “Cinosura, Ursa Minor, has four bright stars on one side arranged in a square shape; there are three bright ones in the tail. They total seven. Under these the star appears that is called Polaris, around which it is believed that the whole sphere is turning.”73 In keeping with the Carolingian reformers’ aim to cleanse the descriptions of the constellations of pagan mythological associations, the only reference to the role the bears played in saving Zeus from Cronus lingers in their alternate names. According to the legend, Haelice and Cinosura attended to the infant god for a year in a cave near Mount Ida at Lyctus. In addition, the Carolingian author omitted any reference to the shipping practices of the Greeks, who navigated with the assistance of Ursa Major, and removed the reference in the Phaenomena to the superior navigational skills of the Phoenicians, who relied instead on Ursa Minor. The little bear reportedly revolves in a tighter orbit around Polaris, yielding a lower relative error for Sidonian sailors.74

The loss of the navigational anecdote from the Phaenomena is a significant one. Navigation was one of the most celebrated uses of the constellations from antiquity into the medieval period, and there was no obvious reason for the clerics to rid the star catalogues of these pragmatic applications. This removal was a deliberate hermeneutic maneuver. The Handbook of 809 demanded a list of star pictures. Telling time was a practical concern of Frankish ecclesiasts such as Drogo, whereas the benefits of the constellations to Phoenician seafaring were not a priority within the cloister walk or cathedral precinct.

Like Ursa Major, Ursa Minor is brown with black highlights. Especially noteworthy are the efforts at rendering the paws, and the eye delineated by a heavy lid under a harsh eyebrow and a beady pupil. Although there was an effort made to capture the ursine form in both images of the bears, neither displays an overall attention to the texture of their coats.

The next constellation in the series is Serpens (plate 1), which weaves between the bears near the north celestial pole. This image of the constellation Draco resembles the style of other serpents painted in Metz during the ninth century, as noted in chapter 1. Since the archetypal Handbook of 809 arose in the court at Aachen in the years following the synod, 809–12, the style of the archetypal paintings would undoubtedly have reflected the stylistic trends associated with a later phase of the development of Charlemagne’s court school. The juxtaposition of three blue tonal values suggests the rounded form of the serpentine flesh. First, a light blue wash laid in the base color of the image, and then the Carolingian painter adapted a technique common to late antique fresco painting to model the forms.75 The progressively darker shades of blue indicate shadows on the serpent, but also approximate the scaly texture of the reptile: “The serpent which lies in the space between the bears has five bright stars in its head and ten stars throughout the whole body. They total fifteen.”76

It is important to underscore that although both the text of the De ordine and its imagery in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 hark back to earlier Aratean traditions, the text itself could not provide a painter with the pictorial cycle. For the pictures in the Handbook of 809, the artists had to look to illustrated Aratean manuscripts or other illuminated codices available in the ninth century. Since star pictures regularly supplied visual summaries of the information included in their texts, odd iconographic details could be carried over between manuscripts when old pictures were consulted in illustrating new texts. Sometimes artists employed stylistic devices (such as the stippled modeling of the serpent’s flesh) that could not have been derived from the text. Texts exist in visual cultures, too, and artists executing their commissions naturally draw on a multiplicity of sources. For this study, I emphasize Carolingian astronomical manuscript illumination for the sake of economy and to clarify meaningful aspects of the Frankish contribution to early medieval astronomical illustration.

The painters in Metz used the scoring on the opposite side of the handbook’s folio 54v as a guide for the undulating twists of the serpent’s body. This was a common practice in the atelier making these star pictures, and a similar layout recurs throughout the pictorial program. The form of the serpent adheres to a standard twisting shape also seen in the Leiden Aratea, despite the tendency of painters in Metz to employ their style of visual parataxis, eliminating the bears. The space remaining at the bottom of folio 54v, however, permitted the introduction of an additional bend in the snake’s body. This reveals the extent to which the pictures in Drogo’s handbook were made by creative painters who made ad hoc, innovative decisions rather than merely introducing all of their images copied in rote fashion from diverse sources.

The next image, on folio 55r, depicts Hercules (plate 2). The painter modeled the figure of Hercules with three ochre flesh tones. The use of three shades resembles the technique for modeling the scaly flesh of the serpent on folio 54v. The hero’s protruding, heavy brow and pupils resemble those of Ursa Minor. These miniatures can be attributed, then, to a first hand. The text explains that “Hercules, of whom it is said that he is kneeling, has one star in his head, one in his arm, one bright star in each shoulder, one star in the left elbow, one in the same hand, one in each hip, two in the right leg, one in the foot, above there is one in the club in the right hand, there are four stars in the lion pelt. They total sixteen.”77 The image of Hercules includes a visual reference to the Aratean character known as the kneeling one, or “Engonasin,” here dubbed “Ingeniculo.” Aratus explained that the figure tilled the earth, like a farmer.78

As Florentine Mütherich has noted in her discussion of the miniatures in the Leiden Aratea, the connection between Hercules and the kneeling figure was made at an early time and pervades the imagery of the Aratean manuscripts. A Revised Aratus manuscript, such as the Cologne Aratus, instead represents Hercules attacking the Serpent or Hydra (Draco), who is wrapped about the Tree of the Hesperides (fig. 8). This scene better illustrates certain scholia attached to the Germanicus translation of the Phaenomena.79 The artists who created the pictorial cycle for the Handbook of 809 removed the mythological battle, while keeping the older visual reference to the “one who kneels.” In Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809, the painter decided to portray Hercules from the front rather than in the quasidorsal view displayed by the miniature in Cologne.

The visual references to the defeated Nemean lion and the club of Hercules gave the painters in Metz captivating narrative details to portray. In this respect, the image seems at odds with the desire to create a sterilized, Christian view of Hercules. Be that as it may, there remained a need, in compliance with the pedagogical goals of the original handbook, for the artists to render a form recognizable as the standard type of Hercules/Engonasin. The educational aims of the handbook vied with the clerics’ desires to sanctify the pictures, precisely because the classical content of a figure such as Hercules could not be separated from its form. The description of Corona precedes an image (plate 2) of a laurel with a jeweled clasp: “The crown has eight stars placed in a circle of which three are bright ones that abut the head of the northern serpent.”80 Curiously, the artists painted the laurel in the same ochre hues as their depiction of Hercules. Green was used later—for the image of Piscis Magnus on folio 61v (plate 15), for example—so this hue was available to the painters in Metz. This suggests that these miniatures with the brownish hues at the beginning of the handbook are all the work of the first painter. The economical reuse of the pigments for the laurel crown and for Hercules (who is stylistically related to the image of Ursa Minor) reinforces the idea that all the paintings thus far are by a single hand. Although stylistic analyses of scientific manuscripts are not a common concern for historians of either art or science, this has led to the inaccurate dismissal of the qualitative richness of certain scientific or philosophical manuscripts, and to ignorance about the sorts of teams that were manufacturing medieval books that were not overtly biblical for meditation and study.

The next image also conforms to the design strategy of visual parataxis (plate 3).81 It is true that the Serpentarius, “the man wrapped about with a serpent,” also known as Ophiuchus, would be meaningless without his reptilian adversary in the picture:

Serpentarius, who is called Ophiuchus by the Greeks, has one bright star in the head, one bright star on each shoulder, one bright star on each foot, three stars in the left hand, four bright stars in the right hand, a single star in each elbow, a single star in each knee, a bright star in the right leg. They total seventeen.

The serpent, which he holds in his hands, has two stars in its mouth and four dim ones in the head, although it has two stars in the area up to the hand, and it has fifteen stars in the bend of the body. They total twenty-three.82

But here, too, the artists deviate from a type of Aratean image that portrays Serpentarius trampling Scorpio, as on Leiden folio 10v, for example. Serpentarius and Scorpius (plate 3) each have their own miniatures in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809, according to the pervasive paratactic design preference for a single picture per constellation. The artists who had made the cycle of images for the computistical manuscript in Cologne also separated out the pictures, accordingly, into two scenes on folio 157r–v of the Cologne Aratus:

Scorpius has two stars on each claw, or preferably both lips, before which there are three bright ones, of which the one in the middle is brighter; there are three bright stars on the back, two in the stomach, five in the tail, and two stars in the spine. They total nineteen. Before these stars four more were placed, whether they are considered to be in the claws or the lips, which are called the “chele of Scorpio,” and that were assigned under the circumstances to Libra. On account of its size it [Scorpio] was in two houses of the zodiac. So, it [Scorpio] was divided into the space appropriate for two zodiac signs.83

The history of the zodiac is divided into two discrete phases. In the early phase, around the late sixth century B.C.E., there were eleven accepted signs of the zodiac. Scorpio and Libra were conflated into a large-clawed creature reminiscent of a lobster. This tradition harks back to such ancient astronomers as Anaximander (d. 546/545 B.C.E.), Cleostratus of Tenedos (active ca. 500 B.C.E.), and Oenopides of Chios (active in the second half of the fifth century B.C.E.). After Alexander the Great (d. 323 B.C.E.), the twelve-part zodiac wheel gradually became normative throughout the Mediterranean.84

The introduction of a pithy tidbit from astrological history into the otherwise terse descriptions of the constellations is intriguing. The scientific writers from Corbie apparently found the fact noteworthy. Two points should be noted here. First, the Carolingian author was aware of not just the standard twelve-part zodiac but also of the alternate ancient eleven-part zodiac system. This suggests that the ninth-century writer of the De ordine had a sophisticated understanding of the history of astrology. Second, the Handbook of 809 as a whole was first and foremost an astronomical-computistical treatise. The author of the De ordine emphasizes the relationship between the twelve months of the year and the corresponding twelve-part series of zodiac signs associated with the calendar, and is also aware to some degree of the problematic impact of equinoctial precession on such alignments.85 Depictions of the months and their related signs in Western medieval manuscripts date back at least as far as the Calendar of 354, and calendrical illustrations, such as a cycle of the months (consider fig. 22), embellish manuscripts to the end of the late Gothic period.86

The image of Scorpius/Scorpio87 in the handbook includes the long pincers mentioned in the text, and it therefore alludes to both the standard form of Scorpio and arguably to its more ancient prototype (belonging to the eleven-part zodiac cycle). This was also the form of Scorpio adopted for inclusion in the Revised Aratus from Cologne on folio 157v. In Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809, the dark brown and black underdrawing yields a sophisticated reticulation of the arachnid’s form.

The next painting in Drogo’s handbook, on folio 56r, is of Boötes, otherwise known as Arctophylax (plate 4). According to Aratus, Boötes endlessly prods the circumpolar constellations of the Great and Little/Lesser Bears as they circle the north pole, which is why the Carolingian painter presents him with his shepherd’s crook: “Boötes, who is called Arctophylax by the Greeks, has four stars in his right hand that do not set, and in his head he has one bright star. He has one star in each shoulder, one star per pectoral muscle with the brighter one on the right, beneath one pectoral muscle there is a light star. In the right elbow there is one bright star. Between both knees there is a bright star, and there is one star per foot. They total fourteen.”88 There are losses to the head of the figure in Drogo’s book that probably took place at the time of the seventeenth-century rebinding (discussed at the end of chapter 1), when the early modern bookbinders cropped the folios. Enough of the brownish flesh-tones and blue mantle remain to warrant an attribution to the first painter. The characteristic large eye resembles other eyes found in the miniatures of Hercules and Ursa Minor.

This first artist also painted the angelic vision of Virgo (plate 4): “Virgo has one light star in her head, one star per shoulder, on the left upper arm/wing she has one light star, on the right upper arm/wing she has one star, she has one star per elbow, one star per hand, and on the left there is a brighter star called ‘the Spica, the ear of grain,’ in the tunic there are six dim stars, there is also one star per foot. They total eighteen.”89 The maiden Dike is referred to by Aratus in the Phaenomena and is alluded to in the Carolingian description of Virgo.90 The winged goddess of Justice, who retreated from earthly life according to the mythological tale, was arguably reinterpreted in an angelic form by the Christian painter. As the winged harbinger of justice, the mythological presentation of Virgo held her ear of grain or sheaf in her left hand, according to the text. This is highly significant, because Carolingian representations of the constellation Virgo differed greatly. She holds three sheaves of grain in her right hand in the Basel Scholia on folio 18v, whereas she holds scales in her role as a personification of Justice in the manuscripts of the Recensio interpolata such as Saint-Gall 902, page 86.91

The conscious removal of the scales, which identified Virgo in her mythological role as winged Justice, permitted the painter of the maiden in Drogo’s handbook to sanctify the representation of the zodiac sign. This innovative form removes the pagan mythological content from the image of Virgo, just as the author of the De ordine in Corbie made every effort to omit mythological references from the text. This unified editorial vision provides the best evidence for the hypothesis that Adalhard of Corbie was instrumental in the development not only of the text but also of the pictorial program for the original Handbook of 809.92 The lack of scales is also an intelligent scientific reaction to the content of the previous passage treating Scorpio: since the scales qua Libra had been removed from Scorpio, it would have been odd to pass them along to Virgo and include them in either her description or her depiction.

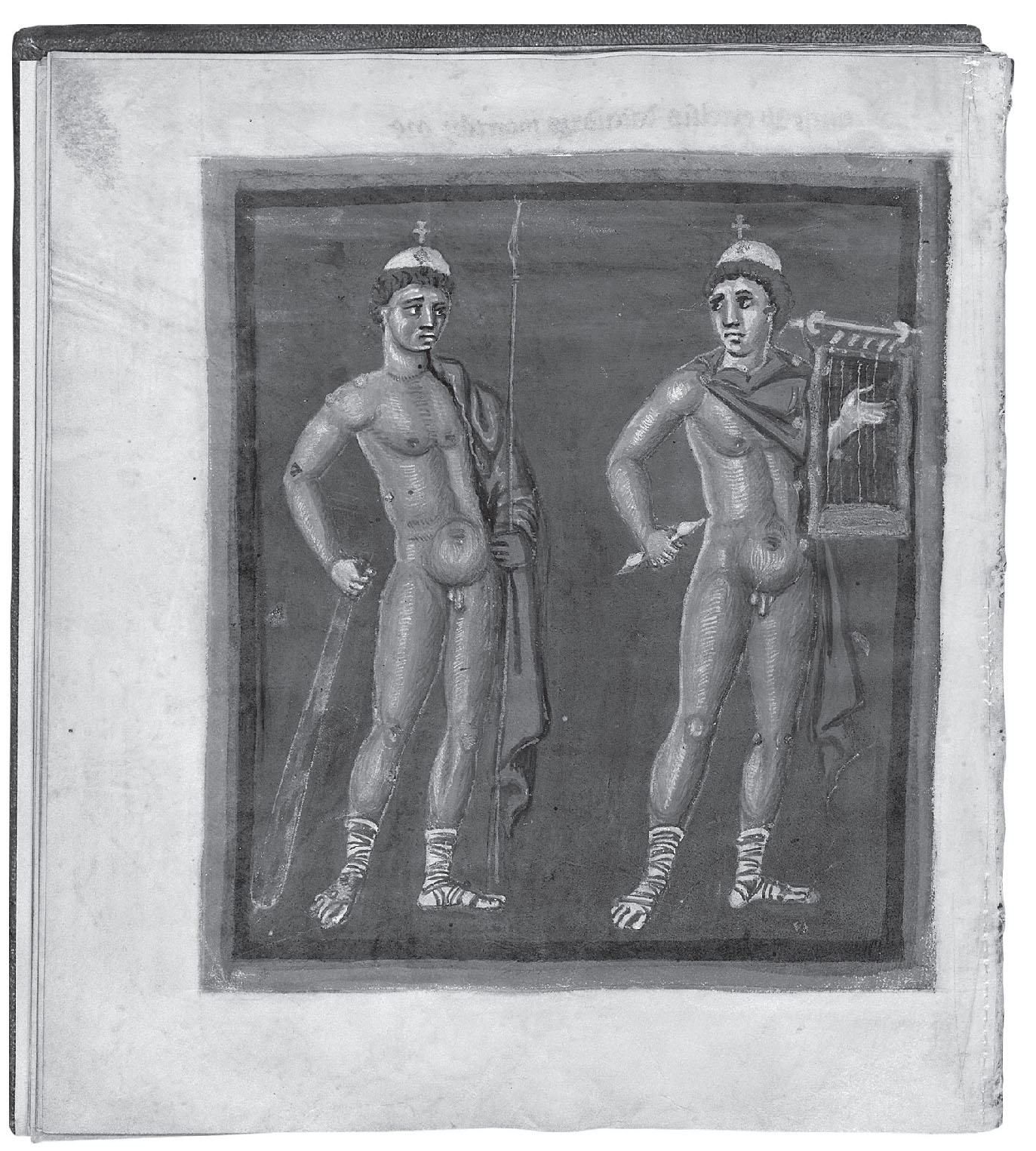

The salmon hue used for the overtunic worn by Virgo is also used for the mantles worn by the curiously sexless (censored) Gemini twins (plates 4–5). Granted, gender-neutral figures are common in early medieval art. The relative uniqueness of this decision in Drogo’s copy of the Handbook of 809 becomes apparent, however, when that depiction of the nude Gemini is compared with other copies of the Handbook of 809 displaying sexual organs (figs. 36, 38). The manner of painting the eye sockets makes it clear that this image was also painted by the first hand. The faces of the Gemini twins, especially the one on the left, recall the linear construction of the face also found in the image of Cepheus on folio 57v (plate 7). This early medieval technique for rendering the face of the figure requires a z-shaped line that begins with a heavy brow, descends as it defines the contour of the nose, and then ends with a line that defines the bottom of the nose. Two tick marks frame the philtrum of the upper lip. One or possibly two roughly parallel lines define the lower lip and seemingly dimpled chin of figures like these in early medieval manuscripts. When a figure stands in a three-quarter pose facing left, like the left-hand twin of the Gemini, the z-shaped line begins on the proper right side of the figure’s face, corresponding to the viewer’s left (plate 5). Examples of figures looking toward the right with such conventionally rendered faces include Virgo on folio 56r (plate 4) and the right-hand Gemini twin on folio 56v (plate 5):