The primary source of Jewish religion is the Hebrew Bible, consisting of twenty-four books divided up into three sections: Torah (the Pentateuch), Neviim (the Prophets) and Ketuvim (the Writings or Hagiographa). Next in importance to the Bible is the Babylonian Talmud, a collection of rabbinical traditions edited in the fifth/sixth centuries CE, containing the main teachings of the oral Torah. Other early rabbinical writings, such as the Palestinian Talmud (fourth/fifth centuries) and midrashic commentaries on the Bible, are less authoritative than the Babylonian Talmud, which itself is an extended commentary to the Mishnah (a work redacted at the end of the second century). The most influential medieval works are the commentary of Rashi (1040–1105) on both the Bible and the Babylonian Talmud; the great law code, known as Mishneh Torah, of Maimonides (1135–1204), and the same author’s philosophical magnum opus, The Guide for the Perplexed, which reinterprets Jewish theology in Aristotelian terms; and the collection of mystical traditions, known as the Zohar, which was written or edited by Moses de Leon (1240–1305). (See figure 1.1.)

In the late middle ages the standard code of Jewish law and ritual (halakhah), the Shulchan Arukh or ‘Prepared Table’, was written by Rabbi Joseph Caro (1488–1575), who included the customs of Spanish and oriental Jewry, and was added to by Rabbi Moses Isserles (1525–72), who incorporated the customs of central and east European Jewry. This work has shaped the practice of Jewish communities throughout the world.

In the modern period rabbinical writings have mainly taken the form of commentaries on pre-modern texts, and Responsa. Responsa literature dates back to the early post-Talmudic period, and consists of published answers to questions about matters of law or ritual. In the changing environment of modernity many new situations have arisen calling for a reinterpretation of Jewish law and its application to differing circumstances. Rabbis have dealt with such issues in Responsa, which if their author is an acknowledged halakhic expert may be collected together and published. Since the mid-nineteenth century a renewed interest in Jewish theology has been stimulated by the contact of Jewish thinkers with modern European thought. The various sub-movements within Judaism – Modern Orthodox, Conservative, Reform, Liberal, Reconstructionist and Zionist – have all produced works reflecting their own ideological understanding of Jewish existence and Jewish identity.

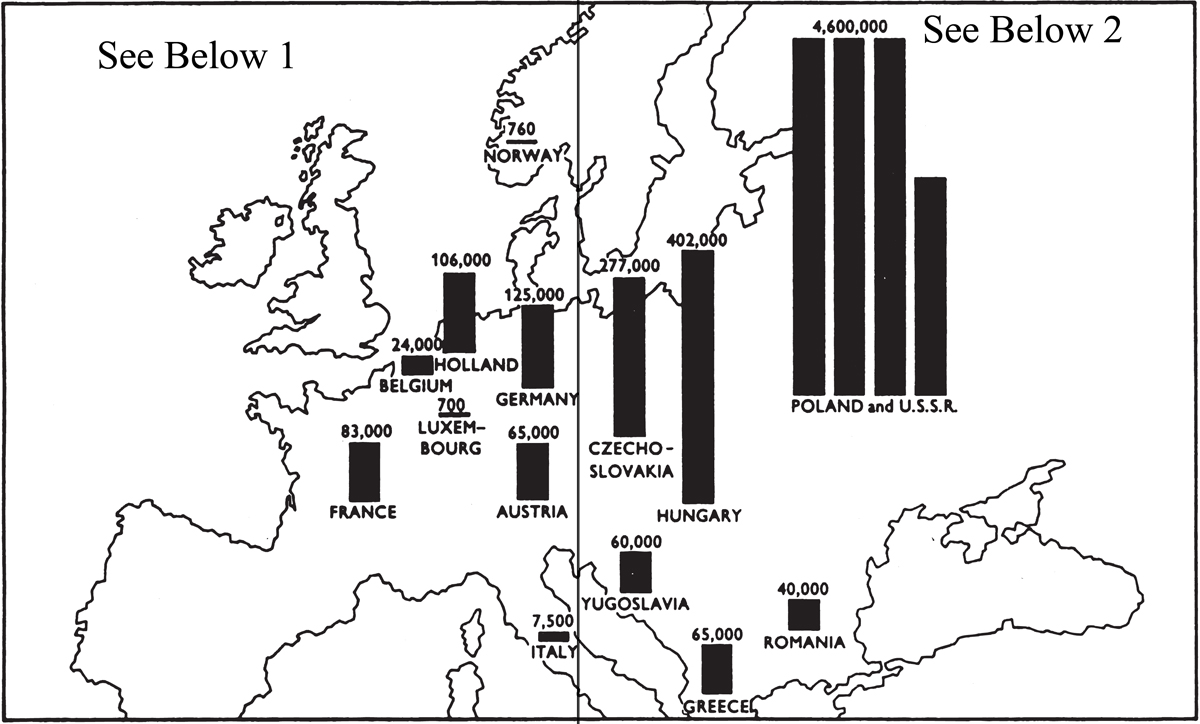

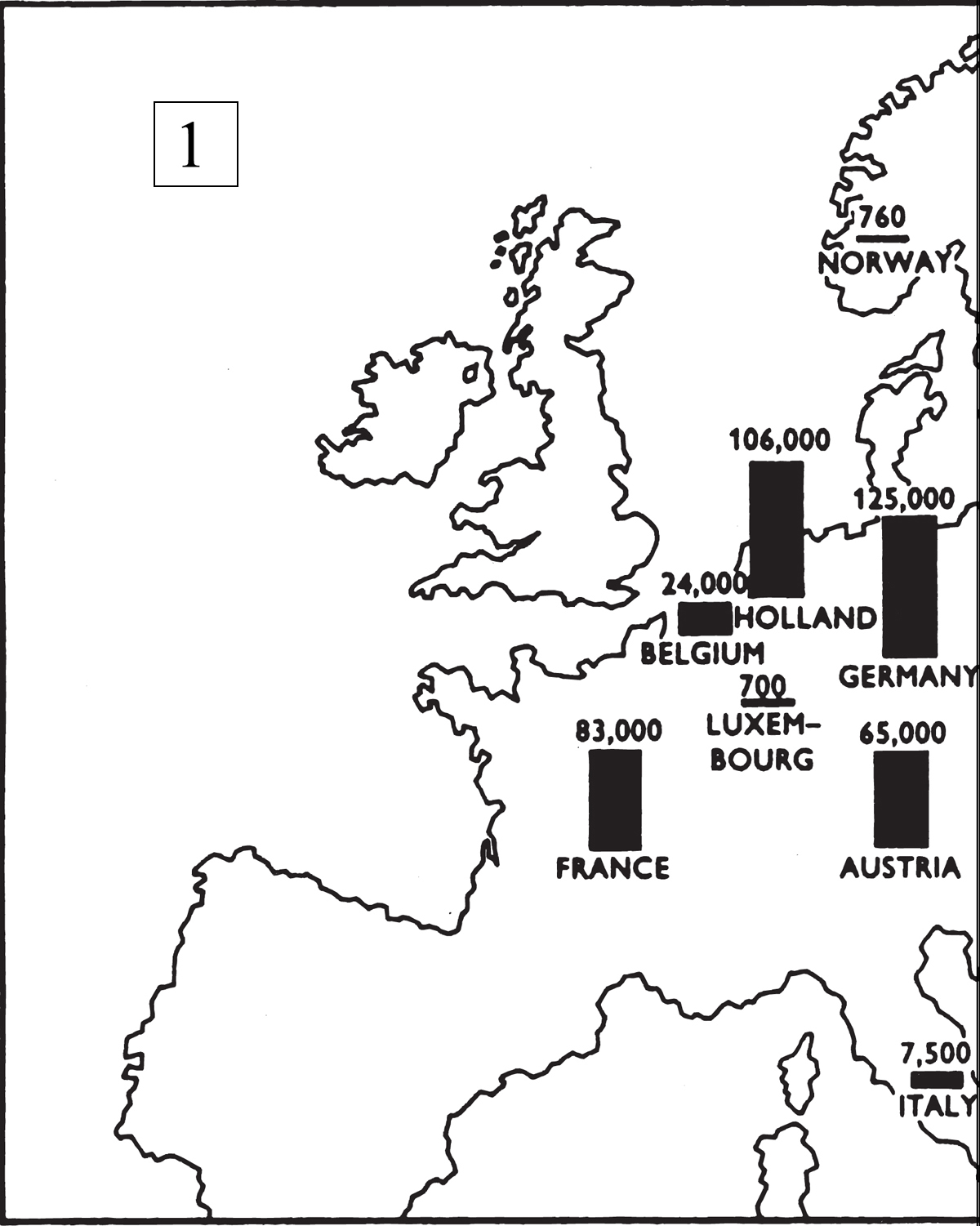

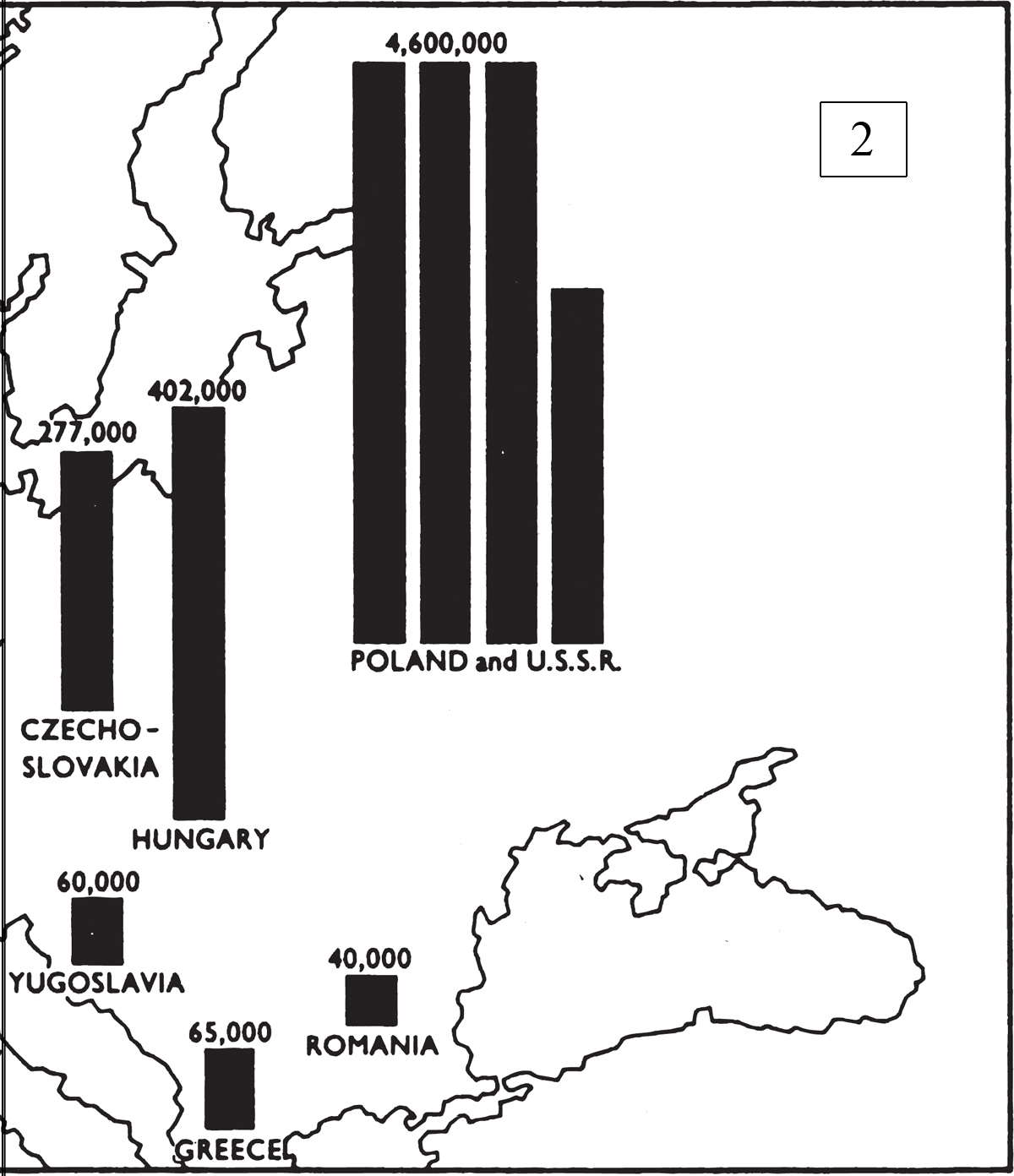

The modern religious Jew, whether affiliated to an Orthodox, Conservative, Reconstructionist, Reform or Liberal synagogue, sees him- or herself as a member of a faith community which goes back some 4,000 years to its origins in the Patriarchal period of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob. For religious Jews the past is not merely of antiquarian interest; it lives on in the rituals out of which their religious life is structured, in their beliefs, and it is constitutive of their very identity as Jews. Since the eighteenth century, when Jews began to move en masse out of the medieval European ghetto (segregated area) into modern society, Jews have had to grapple with the challenges to tradition presented by the norms and beliefs of a scientific understanding of man and the world (see figure 1.2). Over the last half-century they have had to readjust their outlook in the face of the Nazi-inspired Holocaust, in which about 6 million Jews were brutally killed merely because they were Jews (see figure 1.3), and in the light of the rebirth of a Jewish national home in the land of Israel after 2,000 years of exile.

Today there are nearly 14.5 million Jews in the world. The biggest demographic concentration is in the US, with just under 6 million Jews, followed by the State of Israel (over 3.5 million), and then by the countries of the Soviet Union (just under 2.2 million). The rest of the Jewish population is scattered throughout the world, with sizeable communities in France, Britain, Canada, South America and South Africa, and with much smaller concentrations in a host of other countries (see figure 1.4). Because of the political situation in the former Soviet Union, Jews there made little contribution to the cultural, intellectual and religious life of world Jewry. The two main centres of Jewish life are therefore in the North American continent and in Israel. The majority of Jews in the former, and approximately half the Jews in the latter, are Ashkenazi Jews of central or east European origin who share a religious subculture with Yiddish as its lingua franca. The other main component of Jewry is the Sefardi-oriental grouping whose culture is based round the traditions brought by Spanish and Portuguese refugees from the Iberian peninsula, in the late fifteenth century, to the Jewish communities of the Islamic world with whom they merged [35].

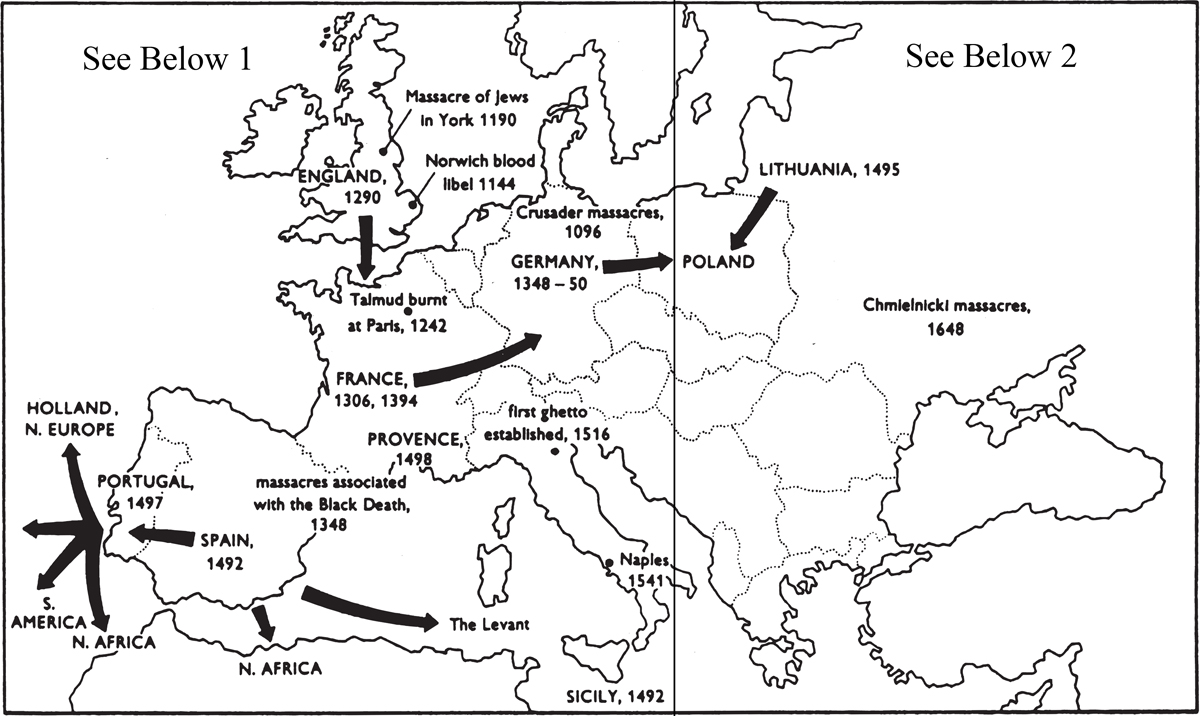

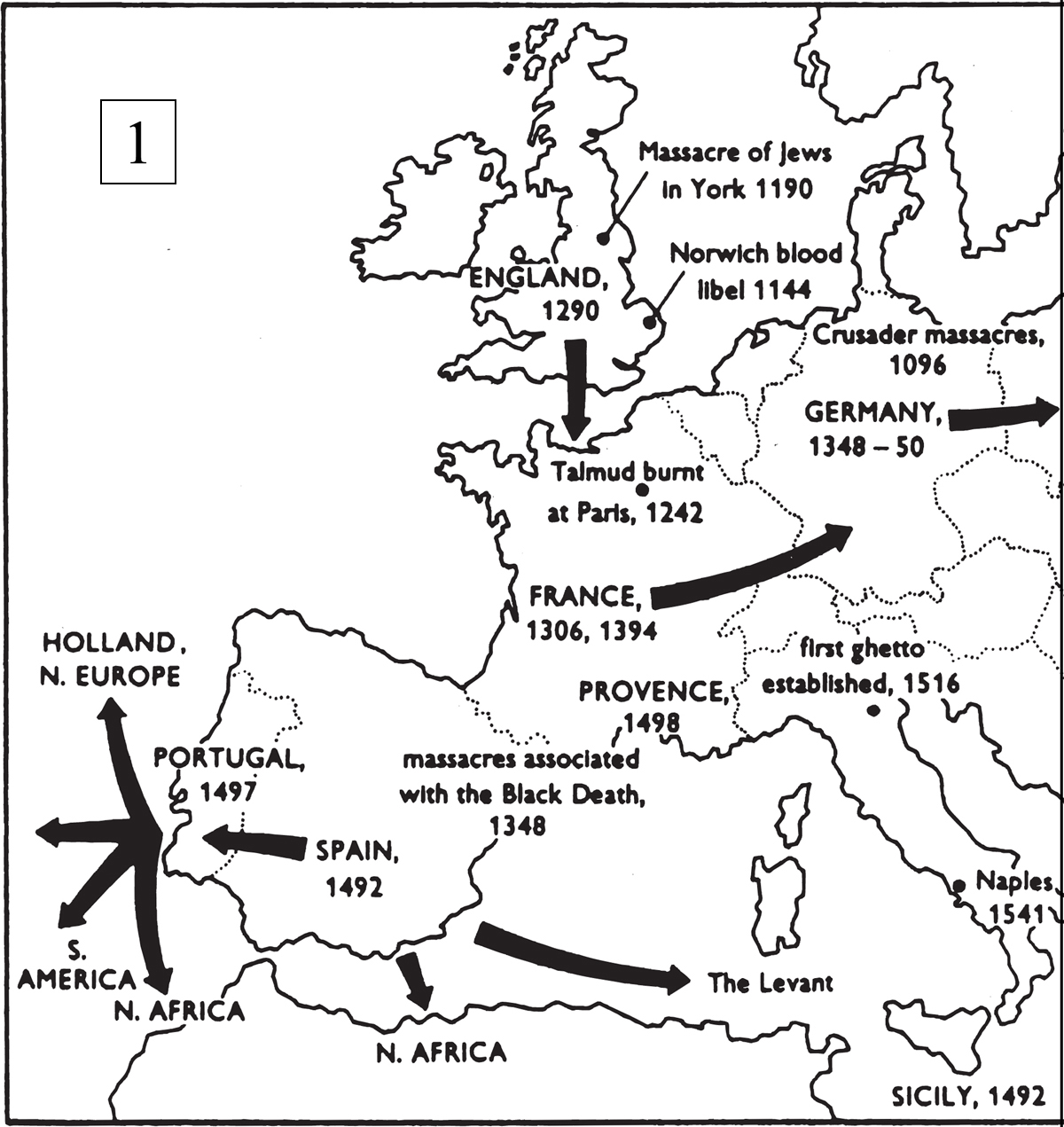

Figure 1.2 Dates of expulsions of Jews from Christian Europe and main sites of anti-Jewish persecution

Figure 1.3 The destruction of European Jewry during the Nazi Holocaust (figures represent the minimum estimated casualties)

During the last few centuries it was the Ashkenazim who were the pace-setters in Jewish life. They were the founders and leaders of the Zionist movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, whose efforts eventually brought about the establishment of a modern Jewish state. They were the initiators of modern Jewish life, emerging from ghetto life in Germany and France to confront the European Enlightenment, and to set up reforming movements whose purpose was to adjust the religion of the Jew to the demands of modernity. Most of the Sefardim lived in Islamic countries and until the twentieth century were barely touched by the new worlds of science, literature and philosophy which did so much to undermine traditional religious life. The Nazi massacres of Jews just before and during the Second World War decimated the old established centres of Ashkenazi Jewry [20: 533]. They were the latest, and most horrific, manifestation of European anti-Semitism, from which Ashkenazim had suffered down the centuries [21: XVIII]. The life of Jews in Christendom was rarely secure, and pogroms (attacks against Jews) were always likely to break out, since the Christian Church taught that Jews were Christ-killers who continued to bear responsibility for the crucifixion of Jesus, and were allied with the devil [31]. Relationships between Sefardioriental Jews and their Muslim hosts were on the whole much better than those between their Ashkenazi brethren and the Christians among whom they lived. Although Islam treated the Jew as a second-class citizen, who had to pay special taxes, and imposed many restrictions on his life and behaviour, it did not have the same theological antagonism to Judaism which Christianity had. Christianity saw itself as the New Israel, the Covenant between God and the Old Israel as recounted in the Bible having been superseded by the life, death and resurrection of Jesus. The very continuity of Jewish existence and the claim of Judaism that the Messiah had not yet come and the world was still unredeemed, were a continual challenge to Christian teaching. Islam, by contrast, saw Jews as protected citizens who it was hoped would one day recognize the truth of Islam but were not to be forcibly converted to the faith of Muhammad. It was only at times of Islamic fanaticism that such forced conversions of Jews were attempted. Christianity was more aggressive in its policy of converting Jews, threatening those who resisted baptism with expulsion, confiscation of their property and ultimately death.

Despite the differences between Ashkenazim and Sefardim, which may be ascribed largely to the wider cultures of Christianity and Islam and their effect on Jewry, they share in common the basic elements of rabbinical Judaism which characterized it from the time the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE. Though customs are different in the two communities the ritual practices of both follow the rulings of the sixteenth-century code of halakhah, or religious behaviour, the Shulchan Arukh (figure 1.1). Educational methods also differ, but the content of religious education is essentially the same: the intensive study of the Babylonian Talmud [3] and its commentaries and to a lesser extent of the Hebrew Bible and its commentaries. The beliefs of both Ashkenazim and Sefardim turn upon the same typological images: the redemptive acts of God in history as exemplified in the Bible, promising the final redemption at the dawning of the messianic age; the special role of Israel as the people with whom God has entered into a covenantal relationship and to whom he has given his teaching or Torah; the need for the Jew to affirm the unity of God, negate all idolatrous thoughts or practices, and obey the mitzvot or commandments of God contained in the Bible and in the oral teachings of the rabbis (the ‘teachers’, religious leaders in the post-biblical period).

In the middle ages it was Ashkenazi Jewry which was culturally the poor relative, unable to participate in the wider interests of Christian society and having to concentrate its intellectual life on the study of rabbinical literature. The Jews of Spain and Portugal, who were eventually to give Sefardi-oriental Jewry its distinctive culture, were at the forefront of the two great movements which formed medieval Judaism: the synthesis between Judaism and Greek philosophy; and the most important stream of the Jewish mystical tradition, the Kabbalah. Jews in Islamic lands first came into contact with philosophy in Arabic translation, and because of the tolerance of various Muslim rulers were able to participate fully in the cultural life of their host countries. The most outstanding product of medieval Jewish philosophy was The Guide for the Perplexed, written towards the end of the twelfth century by Moses Maimonides [17]. Maimonides grew up in Spain but fled with his family from the persecution of a fanatical Islamic sect, spending most of his mature life in Egypt. The Guide reinterprets biblical and Talmudic (from rabbinical traditions of the early Christian era) teachings in Aristotelian terms, emphasizing that many of the descriptions of God found there are anthropomorphisms which must not be taken literally, for any belief in God’s corporeality is heresy. Maimonides also explains the function of the Jewish rituals in terms of the historical situation of the biblical Israelites, and the need for man to be refined in his moral outlook and his beliefs to perfect himself in the service of God. In another of his works Maimonides, for the first time in the history of Jewish doctrine, lays down thirteen fundamentals of Jewish belief the negation of which would lead the Jew into heresy [13]. Apart from the Guide, Maimonides’ other major contribution to Judaism was his all-embracing halakhic (or legal) code, the Mishneh Torah or Yad Ha-Chazakah. This included theological material based on Maimonides’ philosophical understanding of Judaism, and had considerable influence in raising the intellectual horizons even of those Jews who restricted their education to the Talmud and codes. All of the major contributions to medieval Jewish philosophy came from Spain or from areas dominated by Islam such as north Africa and the Orient. Though some Ashkenazi scholars subsequently read the philosophical works of their co-religionists, Ashkenazi culture as a whole did not absorb the ethos of free inquiry or the consequent broad-based perspective on Judaism which was current in parts of the Islamic world. The Ashkenazim in northern France and Germany, and later on in Poland, Lithuania, Hungary and Russia, developed a very intricate system of study of Talmudic literature, and turned in on themselves away from interests which were more theological and general in nature. Ashkenazi religiosity was inclined to pietism, to an awareness of humanity’s finiteness and sinfulness, and to a form of mysticism in which the adept underwent a severe regimen of spiritual training leading to a vision of the divine Glory seated on the heavenly throne [27: III]. Many elements of folk religion, with strong magical overtones, were absorbed by Ashkenazim and indeed came to be accepted as normative customs on a par with the halakhah itself.

The great flowering of medieval mysticism, however, took place precisely in those areas which had experienced the most intense development of philosophical religion, namely in Spain and Provence. In part the Kabbalah spread as a reaction to the changes that philosophically minded intellectuals had made in the traditional Jewish outlook. They had allegorized away much of the substance of Jewish theology, and reinterpreted the halakhic rituals as spiritual ideas. The great monument of kabbalistic religion was the Zohar [37], written in Spain but claimed by Moses de Leon, its promulgator, to be the teachings of the second-century sage R. Simeon bar Yochai [27: V, VI]. In this work we find a reversion to the modes of Talmudic Judaism, the rituals being interpreted as the mystical contact points between humanity and the divine. The Zohar, however, goes beyond the strengthening of halakhic norms by interpreting them as the primary means whereby the divine substratum underlying the world is kept in harmonious relationship with it. It also advocates a whole series of new rituals of its own, emphasizes the demonic forces at work in the creation, teaches that the difference between Jew and Gentile is a question not merely of degree but of kind, the Jew possessing a quality of soul absent from the non-Jew, and generally reinforces the sense of the magical which theologians influenced by Greek philosophy had argued was inimical to monotheistic belief.

Sefardi culture was deeply influenced by the Kabbalah of the Zohar, which began to circulate at the end of the thirteenth century, and by the kabbalistic teachings of Isaac Luria among a community of Spanish exiles in Safed, northern Palestine, in the late sixteenth century. While the philosophical religion of the middle ages left great works of literature to future generations, it was essentially an elitist perspective on Judaism. Kabbalah continued as a living movement within Judaism, eventually shaping exoteric religion through its special rituals and ideological assumptions about the emanations with which God created the world, the nature of the soul, the task of humanity in the world, and the means by which the messianic redemption could be brought about. At both its scholarly and its popular level, Sefardi Jewry was transformed into an amalgam of rabbinical and kabbalistic Judaism, with its central images drawn from both the Bible and Talmud, and the Zohar and Lurianic corpus.

Although kabbalistic ideas spread among the Ashkenazim they never gained the almost complete dominance that they had among the Sefardim. Ashkenazi culture had never risen to the rarefied, and somewhat dangerous, heights of this synthesis with philosophy. It had its own traditions of pietism and mysticism, and its profound system of intellectual analysis of Talmudic and halakhic texts meant that it set as much store by scholastic knowledge as by religious or mystical intuition. The only major movement among the Ashkenazim almost entirely inspired by the Kabbalah was the Chasidic movement, which began in eastern Europe in the eighteenth century. This was originally a populist revolt against the scholarly elitism of the rabbinical leadership in Ukraine and southern Poland, emphasizing the worth of the ordinary, unlettered Jew who could not engage in the very demanding life of Talmudic studies. Chasidism adapted kabbalistic teachings about the divine emanations within all creation, and singled out the inner state of the worshipper, rather than his understanding of the tradition, as the primary value in the service of God. Since the humble and simple Jew could attain to a state of devekut, or inner cleaving to God, he could play a central role in the spiritual scheme of things despite his ignorance [19: III; 33: 107]. In the course of time even the Chasidic movement gave way to the predominant Ashkenazi tradition of the meticulous following of halakhic norms and the study of the Torah as the main ideal of the religious life. Although it maintained its separate identity, and formed self-contained communities around the Chasidic rabbi or tzaddik, Chasidism ceased to be guided by the kabbalistic impetus and became part of Ashkenazi orthodoxy.

In the nineteenth century modernizing Jews associated with the early stages of Reform Judaism found the elements of kabbalistic Judaism among Ashkenazi culture to be the most recalcitrant to change, and to encapsulate the ethos of what they regarded as medieval superstition and magic. They had no sympathy for its symbolism and no understanding of its contribution to Jewish spirituality. To them it represented the worst form of the narrow-minded and obscurantist ghetto religion. It was only in the twentieth century that Jewish academic scholars shook off these prejudices and began to investigate the profound religious ideas which lay behind the magical and folkloristic elements of Kabbalah. The twentieth century has also seen a reassessment of Judaism by Christian scholars, whose picture had been clouded by the negative attitude of the New Testament to the Pharisees, the spiritual ancestors of rabbinical Judaism. It was customary for Christians to think of ancient Judaism as the religion of the Bible and of modern Judaism as the religion of the Jewish people in the times of Jesus. Behind all this was thë view that Judaism had somehow ceased all development and growth during the first century CE, and that at that period Pharisaic religion was as hidebound and hypocritical as the Gospel authors depict it. Although one still comes across this view in Christian writings about Judaism, it has become less common as a result of the scholarly work of both Jewish and Christian academics [18]. The nature of rabbinical Judaism in the first few centuries CE has been extensively explored, and developments during the middle ages and up to modern times have been fully charted [4]. The great complexity of Judaism, made up as it is of a variety of different strands, makes over-facile comparisons between Christianity (‘the religion of love, of compassion’) and Judaism (‘the religion of law, of divine judgement’), which were so common in a previous age, seem singularly unfounded. Within Judaism there are elements of both faith and works, both divine love and judgement, which have come to be recognized as constituting the very fabric of the religion.

At the centre of Jewish belief lies the faith in one God, who has made the heaven and the earth and all that they contain (Genesis 1: 2), and who took the Israelites out of their bondage in Egypt, revealed his divine teaching or Torah to them, and brought them into the Holy Land. This idea of God’s redemptive acts in history has coloured the Jews’ view of their situation since the biblical period, and proffers the hope that one day the Messiah, or anointed one of God, will come to usher in a messianic age when the Jews will be gathered once again to the Land of Israel. The idea that Israel is a people chosen by God is associated in Jewish consciousness with the revelation of the Pentateuchal teachings to Moses and the Israelites as they wandered in the wilderness after the Exodus from Egypt (c. fourteenth century BCE; the archetype for later Judaism of God’s liberation of the Jews from bondage and suffering). An oft-repeated benediction of the liturgy runs: ‘… who has chosen us from all the nations and given us His Torah [i.e. teaching]. Blessed are you, O Lord, who gives the Torah’ [2: 5, 71]. The Torah of God is not merely identical with the text of the Pentateuch, or even with the whole Hebrew Bible, which is also considered to be divinely inspired, but includes the oral teachings of Judaism, which are thought in essence to go back to the revelation to Moses. The fact that the religion has developed since the biblical period is not unrecognized, but the traditional Jewish view is that the developments all follow the principles of interpretation laid down in that period or are consequences of rabbinical enactments whose purpose was to make fences around biblical religion in order to strengthen it as circumstances changed.

Maimonides’ analysis of the thirteen fundamentals of Jewish belief, although much criticized by subsequent scholars, has come to be accepted as something like the official creed of Judaism [13; 26: 3]. It has the following structure. The first five fundamental beliefs concern God: God is the creator of all that is; God is one; God is incorporeal; God is eternal; and God alone is to be worshipped. In the middle ages both popular piety and certain elements of the mystical tradition were less than happy about the belief in the corporeality of God being regarded as heretical. The popular imagination had always tended to take the biblical and rabbinical descriptions of God more or less literally, while the mystics developed a series of meditations on the gigantic dimensions of the ‘body’ of God, known as Shiur Komah [27: 63], which were not in line with Maimonides’ more philosophical approach to the subject. Since then, however, the incorporeality of God has come to be accepted by all sections of Jewry as representing authentic Jewish doctrine, and the belief that God has physical dimensions or form as heretical [13: IV].

The next four fundamental beliefs concern revelation. They are: that God communicates to humanity through the medium of prophecy; that Moses was the greatest of the prophets to whom God communicated in the most direct manner; that the whole of the Torah (i.e. the Pentateuch) was revealed to Moses by God; and that the Torah will not be changed or supplanted by another revelation from God. The idea of prophetic revelation was seen as a basic element of Judaism in the past, and has continued to play a central role among both Orthodox and modernizing trends in contemporary Jewry, with the exception of the Reconstructionist movement (see p. 43). The other three doctrines have led to great controversy in the modern era, with Reform Judaism emphasizing the message of the purely prophetic books of the Bible more than the Pentateuch with its rituals; accepting the finding of biblical criticism that the Bible in general, and the Pentateuch in particular, are composite texts redacted over a long period of time by different editors; and firmly espousing the view that the biblical traditions have become outdated and must give way to modern religious sensitivities. All this is considered heretical by Orthodox thinkers and is regarded as undermining the very basis of Jewish religion as a response to the revelation of God. Against this, both Reform and Conservative Jews have argued that there is room for the idea of divine inspiration within the Jewish tradition, but that this inspiration is something less than the older idea of revelation by direct communication with the prophets. What is to be identified as divinely inspired and what as purely human within the Bible and Jewish tradition is very difficult to decide, and there has been no general agreement among the different modernizing movements within Judaism [13: X, XI; 30: 223; 22: 290].

The tenth and eleventh fundamental beliefs are in God’s knowledge of the deeds of humankind and his concern about them; and that he rewards and punishes people for their good or evil ways. This is meant to negate the ideas that God has withdrawn from involvement in the day-to-day running of the world, and that there is no ultimate justice. The notion of a God who is interested in the doings of both nations and individuals, and who metes out the deserts of the righteous and the wicked, characterizes the salvation-history of the Bible and is the assumption behind the commandments and laws which presuppose that Jews are free to choose how they behave and are consequently responsible for their choices. Although some radical theologians have questioned these basic assumptions about God, particularly in the light of the killing of millions of Jews by the Nazis, which seems to make a mockery of the idea of a just world and a caring God, they have remained part and parcel of mainstream Jewish thought in the modern world.

The last two of Maimonides’ fundamental beliefs concern the coming of the Messiah (‘anointed one’), a descendant of the line of David, the famed ancient king of Israel, who will usher in the messianic age, and the resurrection of the dead. Both of these doctrines have been considered questionable by sections of Jewry since the beginning of Jewish emancipation in the late eighteenth century. The idea of a personal Messiah of the Davidic line was considered too particularistic and the Reform movement has preferred to talk instead about a universalistic messianic age which will dawn for all humankind [13: 384; 22: 178]. The resurrection was likewise considered a doctrine out of tune with modern ideas about the body and soul, and has been generally replaced among non-Orthodox Jews with a doctrine of the continuing existence of the soul after death. Such a doctrine is also part of traditional Judaism, where it coexists with the belief in the resurrection, and even Maimonides himself in his works devotes far more space to it than to the more formal doctrine of the resurrection. Nevertheless, in an essay about the resurrection, which Maimonides wrote to answer critics who accused him of neglecting this doctrine in favour of that of the immortality of the soul, he makes it clear that Judaism believes in the resurrection even if little can be said in philosophical support of it. The reason why he discusses the soul’s immortality at greater length in his works is that more can be said about it in rational terms. It does seem clear, however, that Maimonides holds the disembodied bliss of the soul to be the ultimate state to which the righteous will attain and the resurrection to be merely a stage, albeit a doctrinally supported stage, prior to this spiritual bliss. The daily prayers offered by Jews contain references both to the Messiah and to the resurrection, and the Reform prayer-book has changed these texts in line with its own interpretation of the doctrines.

The Hebrew language is a very concrete mode of expression, preferring to use stories or images rather than more abstract concepts to express an idea. In a parallel way Judaism expresses its beliefs and attitudes more through its ritual nexus than through abstract doctrine. The earliest work of rabbinical Judaism, the Mishnah (end of second century CE), is concerned with agricultural laws, benedictions, festivals, the relationship between men and women, issues of civil and criminal law and damages, ritual purity, and the temple ritual and its sacrifices. In the discussion and formulation of such issues the rabbinical sages gave expression to the ethos of Judaism. The ordinary Jew today may know little about the sophisticated analysis of Jewish theology and doctrine which went on among philosophers in the middle ages, or about the speculations of the Kabbalists. In so far as he is a traditional Jew, however, his life will be structured around the halakhic rituals which shape his approach to God, to his fellows and to the world about him. For him they are the prime repository of his faith. This is why there is such a large gap between the traditionalist and the modernist. It is not the differences in doctrine alone which divide them, but, more important, the differences in lifestyle, liturgy, festival rituals, dietary laws, marriage and divorce procedures, etc. While variations in practice between one Jewish community and another do not substantially affect the overall religious orientation, the complete modernization of the halakhah by Reform Judaism and some sections of the Conservative movement present a ritual structure which on occasion is almost unrecognizable to the traditionalist, and seems to express a different set of beliefs and values. In what follows we shall describe some of the more important traditional rituals, it being understood that the extent of their observance varies from very strict to very light depending on the degree of modernization of the Jews practising them.

The Jewish ritual year is a lunar year of twelve months, approximately eleven days shorter than the solar year. Leap months are intercalated at regular intervals to prevent the lunar and solar years from diverging too far, since the festivals are tied to the agricultural seasons (see figure 1.5). The year begins in late September/early October with the New Year festival (Rosh Ha-Shanah), which for Jews is a period of divine judgement in which the fate of the world in the coming year ahead is determined. Jews repent of their sins, the ram’s horn (shofar) is blown in the synagogue (see p. 33) summoning man to an awareness of his shortcomings, and the idea of God as the divine king is emphasized in the liturgy. For the two days of this festival Jews eat sweet foods as a symbol of the good year to come, and celebrate to show that they are confident of God’s mercy [33: 173; 25: 145, 156]. The day after Rosh Ha-Shanah is a fast day (Tzom Gedaliah), lasting from dawn till night-fall, commemorating a tragic event in Israel’s past.

Ten days after the New Year is the Day of Atonement (Yom Kippur), a twenty-five-hour fast day beginning at dusk and lasting till nightfall on the following day. All food and drink are forbidden; no leather shoes (a sign of comfort) may be worn; nor may sexual relations take place between husband and wife. Most of the time is spent in the synagogue, seeking atonement from God for past sins, reciting the account of the entrance of the High Priest into the Holy of Holies, the most sacred area of the ancient Temple, which took place on this day, and reading from the Pentateuch and the Book of Jonah. The day is the most solemn occasion of the Jewish year, and synagogues are usually crowded with worshippers, many of whom would not attend at other times. The message of Yom Kippur is that God forgives the truly penitent sinner, but for sins committed against one’s fellow man one must first try to win his forgiveness before turning to God in prayer [33: 178; 25: 151, 161].

Five days later comes the festival of Tabernacles (Sukkot), an eight-day festival in Israel and a nine-day one elsewhere because of uncertainty about when the lunar month began when this was fixed by the sighting of the new moon in the Land of Israel. The Jew lives for the duration of the festival in a little shack or booth (sukkah) covered with branches, remembering the time that his Israelite ancestors wandered through the wilderness after the Exodus from Egypt, protected only by the mercy of God. One of the most important rituals of Tabernacles is the taking of the four species, a palm branch, willows, myrtles and a special citrus fruit, the etrog, which are held together and shaken during the prayers. The first day (outside Israel the first two days) of the festival and the last day (or last two days) are festive days proper and no profane work may be done. During the intermediate days work is restricted but allowed. The last day (or last two days) are celebrated as the time of the Rejoicing of the Torah (Simchat Torah) when the Pentateuchal cycle of yearly readings is completed and begun again from the beginning of Genesis. This ceremony is accompanied by great rejoicing in the synagogue, with singing, dancing and alcohol [33: 180; 27: XIX, XX].

Some two months later Chanukah, an eight-day feast of lights commemorating the victory of the Hasmonean priests over the non-Jewish Seleucid rulers of Palestine in the second century BCE, is celebrated. On each night an extra candle is lit in the eight-branched candelabrum or menorah, until on the last night all eight candles are burning. The lighting is accompanied by benedictions and the singing of a hymn, ‘Maoz Tzur’, recounting God’s saving acts during the course of Jewish history. Chanukah is not a true festival, and normal work is allowed [33: 184; 25: XXIII, XXIV]. A week after the end of Chanukah there is another daytime fast remembering a tragic event which took place in the biblical period. This is known as Asarah Be-Tevet (the tenth of the month Tevet). The month of Tevet is followed by the month of Shevat.

The next month of the Jewish year, Adar, is the most joyous month, on the fourteenth of which the carnival-like festival of Purim falls. This commemorates the events recounted in the biblical book of Esther – how the Jews of the Persian empire were saved from the designs of the villainous Haman. The scroll of Esther is read publicly in the synagogue, once in the evening and once during the day (Jewish festivals always begin in the evening before the nominated day, at sunset). Whenever Haman’s name is mentioned the congregation boo and stamp their feet. Jews often dress up in fancy dress on Purim; they send gifts of food to each other and give charity to the poor. The Purim feast is usually held in the afternoon, and Jews are encouraged to drink alcohol to the point when they cannot distinguish between ‘blessed be Mordecai’ (one of the heroes of the story) and ‘cursed be Haman’, signifying that divine help transcends the normal distinctions of human understanding [33: 186; 25: XXVII, XXVIII].

A month after Purim is the seven-day (eight outside Israel) festival of Passover (Pesach). This festival must always fall in the spring, and commemorates the time of the Exodus of the Israelites from Egypt. No leavened bread may be eaten during the festival and the Jewish house is given a thorough spring-clean to remove all traces of leaven. The staple food eaten during Passover is flat wafers of unleavened bread (matzah). On the first night (outside Israel, on the first two nights) a ritual family meal, known as the Seder, is held. During the meal the story of the Exodus is read from a special Haggadah text, four cups of wine are drunk, and bitter herbs symbolizing the suffering of the Israelite slaves in Egypt are eaten, as are other ritual foods including unleavened bread. The Seder is maintained even among Jews who do not keep up other Jewish traditions, for apart from its purely religious significance as a celebration of God’s redemption it is intimately associated with family ties, which are extremely important for Jews [27: VII, IX].

Seven weeks after the second day of Passover the one-day (or two-day) festival of Pentecost (Shavuot) falls. The period between Passover and Pentecost is one of semi-mourning, and no weddings take place. Shavuot is celebrated as the time when the Ten Commandments were given to Moses on Mount Sinai, and the story of the theophany on Sinai is read in the synagogue. Jews customarily stay up all night on the first night of Pentecost studying the Torah, as if to show that they are ready to receive the word of God once more [33: 193; 25: X]. In the modern period a number of new festivals have been introduced in the period between Passover and Pentecost, associated with the modern state of Israel (Israel Independence Day and Jerusalem Day) and with the Nazi Holocaust (Holocaust Remembrance Day). As yet these have gained only partial acceptance as part of the Jewish ritual year.

Just over five weeks after Pentecost there is a three-week period of intense mourning remembering the events surrounding the destruction of the First and Second Jerusalem Temples in the sixth century BCE and the first century CE respectively. This period begins with a daytime fast (Shivah Asar Be-Tammuz) and ends with a twenty-five-hour fast (Tisha Be-Av), during which no leather shoes may be worn and Jews do not sit on normal chairs but on the ground or on low stools. Weddings are not allowed for these three weeks, and haircuts, the eating of meat and the drinking of wine are restricted – customs about these matters varying between different communities [33: 194; 25: X]. The mourning, though focused upon the destruction of the Second Temple, also symbolizes the sufferings experienced in the exile during the centuries that followed. The memory of what happened thousands of years ago is, therefore, at the same time a living memory of what has been happening since. The Jewish ritual year ends with the lunar month of Elul, falling around September, which is a period of preparation and repentance leading up to the New Year festival.

Aside from the yearly cycle there is a minor festival falling at the beginning of each month (Rosh Chodesh) and, more important, there is the weekly Sabbath (Shabbat), which begins each Friday evening at sunset and lasts till nightfall on Saturday. The Sabbath is a day of complete rest, and even those types of work which are allowed on festivals (associated with cooking) are forbidden. As with other festivals, there is a special liturgy for the Sabbath, and the day is sanctified over a cup of wine (kiddush). Apart from attendance at the synagogue for prayers and the weekly reading from the Pentateuch, much of the day is spent in the family circle. On Friday night the mother lights candles before the Sabbath begins, and on his return from synagogue the father blesses his children before reciting kiddush and making the blessing over two loaves of the special bread (challah). During the three Sabbath meals hymns are sung at the table, and the best food is served. At the conclusion of the Sabbath a prayer (havdalah) is recited over a cup of wine, incense, and a candle flame [33: 169; 25: IV].

A child is considered a Jew if it is born of a Jewish mother; whether or not the father is Jewish is of no consequence for the religious status of the child, according to tradition. A male child is circumcised on the eighth day after its birth, if it is healthy, and is then given a Hebrew name. Circumcision, representing the entrance of the child into the covenant which God made with Abraham and his descendants, is accompanied by a celebratory meal. Up to the age of twelve for a girl, and thirteen for a boy, a child is regarded as a minor. He or she will be gradually instructed in the keeping of Jewish rituals, will be taught Hebrew and will learn to translate passages from the Bible and the prayer-book. At the age of twelve or thirteen the child is regarded as an adult who must keep the halakhic rules in their entirety. Its passage to maturity is marked by a Bar Mitzvah ceremony for a boy, and a Bat Mitzvah ceremony for a girl. The Bar Mitzvah consists of being called up in synagogue to read from the Torah scroll or the weekly portion from the Prophets. This is followed by an often elaborate party to which relatives and friends are invited. The Bat Mitzvah is a relative newcomer to the Jewish scene, having been introduced in modern times to give the girl more of a role in Jewish public life. It usually consists of a ceremony in which several girls participate together, and is more common in Reform communities than in Orthodox ones [33: VIII].

Marriage is a high point in the life of a Jew, for it signifies the setting up of a new family – the family being the basic unit of Jewish ritual. Judaism does not allow marriage with a non-Jewish spouse, and intermarriage between a Jew and a Gentile cannot be performed in a synagogue. Intermarriage is generally regarded as a tragedy for the parents and family of the Jewish partner, although it is an increasingly frequent occurrence in the modern Western world. The desire of a non-Jewish partner to be accepted by the family and community of the Jewish partner is one of the main reasons for the conversion of Gentiles to Judaism today, even though it is not considered to be a particularly good reason for conversion by the religious authorities.

Marriage usually takes place under a decorated canopy in the synagogue, with a minority of Ashkenazi Jews preferring the more traditional setting of marriage under a conopy in the open air. It is not necessary for a rabbi to perform the ceremony; any layman can do so in the presence of at least two witnesses. It has become customary for the rabbi, who is not a priest but an expert on halakhah, to officiate together with the synagogue cantor and to preach a short sermon containing words of encouragement to the couple. The ceremony itself consists of various benedictions over glasses of wine, the giving of a ring by the groom to the bride, the reading of the wedding document, and the breaking of a glass indicating, at the time of greatest joy, a sense of sadness at the destruction of Jerusalem [33: 150]. Marriage is considered a desirable condition for every Jew, since there is a biblical commandment, or mitzvah, to have children. Jews are generally discouraged from remaining single by choice, and religious literature from the biblical story of the first human couple, Adam and Eve, onwards depicts the unmarried individual as an incomplete person. If there is a breakdown of the marriage relationship a religious divorce procedure is necessary before either party is allowed to remarry, civil divorce not being recognized as a means of dissolving the marital state.

Great store is set in Judaism by respect for the aged. Children have a duty to look after their parents; indeed, the honouring of parents is one of the Ten Commandments. In established Jewish communities today old-age homes are often large and well endowed, providing a Jewish atmosphere in which people may spend the twilight of their lives. After death, which is defined in Judaism by the cessation of respiration, burial must take place immediately out of respect for the departed. Orthodox Jews do not practise cremation, and burial has to take place in consecrated ground, which means that Jews have their own cemeteries. It is customary to throw a small amount of earth from the Land of Israel on to the coffin, and some Jews who die in the diaspora (i.e. in the lands of the Jewish dispersion) are even taken to be buried in the Holy Land, particularly in Jerusalem. All this is an affirmation of the belief in the resurrection, which it is thought will take place essentially in the Land of Israel. According to a popular Jewish belief, those who die outside of Israel will have to roll over in subterranean caverns till they reach the Holy Land to be resurrected there. Next of kin have to undergo an intense period of official mourning for the first week after burial. They sit at home on low stools, with their garments rent, and do not wear leather shoes. People come to conduct prayer services in the mourners’ house and to comfort them. The mourning then gradually decreases in intensity, depending on the closeness to the dead relative, allowing the mourner eventually to resume his or her normal place in the community. The ritualized mourning procedure is intended to permit the mourner to express grief, but at the same time to discourage him or her from taking the sense of loss to extremes [33: 163].

The proto-synagogue began in the sixth century BCE, after the First Temple was destroyed, when many Jews were deported in captivity to Babylonia. Its role then was as a house of assembly. It developed markedly after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, eventually becoming the centre for community prayers, for the reading of a section from the Pentateuch on Mondays, Thursdays, Saturdays and on festivals, and for instruction in Jewish teachings. Both the Christian church and the Islamic mosque were modelled after the synagogue prototype. Until the modern period the synagogue was overshadowed by the Jewish home, which was the primary locus of ritual. In the last two centuries, however, with the growing secularization of the home, the synagogue has become more important as the place where Jewish life finds its full expression [33: 197].

The influence of the non-Jewish environment is apparent in the architecture of the synagogue building, and even in some cases in the internal layout. After Jews emerged from the medieval ghetto they looked upon the European church as a model for synagogue reform. The traditional platform at the centre of the synagogue, from which the Torah scroll was read, was moved up to the front, so that the congregation became more of an audience witnessing the religious activities of the rabbi and cantor. The older style of synagogue, still found in many Orthodox communities, was built on the assumption of the equal participation of all worshippers. In the newer-style synagogues the religious functionaries have adopted more of a priestly role.

When praying, Jews face towards Jerusalem, and the ark of the synagogue (a type of cupboard often set behind a curtain) in which the Torah scrolls are kept is set in the Jerusalem-facing wall, making it the focus of prayer. The liturgy consists of three basic prayers, to be said in the morning, the afternoon and the evening. On Sabbaths and festivals there are variations in the liturgy reflecting the special character of the day, and the services are generally much longer than on weekdays [12: VII, X]. A typical Saturday morning service including a sermon would last between two and a half and three hours, while even the longest weekday morning service takes less than an hour. Each service is built round an amidah (literally ‘standing’) prayer which consists of blessings, requests and thanksgivings. On Sabbaths and festivals the requests are replaced by special prayers for the occasion, and an additional amidah is also recited, modelled on the additional sacrifices brought in Temple times. The other main component of the morning and evening services is the Shema (Deuteronomy 6: 4–9; 11: 13–21; Numbers 15: 37–41), which opens with the affirmation of faith: ‘Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One.’ The rest of the liturgy consists of benedictions, psalms, hymns and selections from the Bible. Prayers are led by the cantor or any competent layman, whose purpose is to keep the pace of prayer at a regular tempo and to recite those portions of the liturgy said when there is a quorum (minyan) of ten adult males [33: 209].

The traditional synagogue is run entirely by men; the women do not play a public role, lead the prayers, read from the Torah scroll, preach or indeed sit with the men in the main body of the building (see figure 1.6). They will usually occupy a ladies’ gallery, or sit downstairs behind a partition. Reform and Conservative synagogues (known as temples in the United States) have mixed seating and involve the female worshippers to a far greater extent than Orthodox ones. Women have even been ordained as rabbis in a number of Reform communities. Another difference between traditional and Reform synagogues relates to the covering of the head during prayer. In all Orthodox and Conservative synagogues the male congregants will wear either a hat or a skull-cap during the service, and many Orthodox Jews keep their heads covered even at home or at work as a sign of respect for God in whose presence man always is. Orthodox married women will also cover their hair in synagogue with a wig, hat or scarf, some even maintaining the covering at other times as well. In many Reform congregations, particularly in the United States, the covering of the head in synagogue is not mandatory.

The home and family are very important for Jewish ritual. The doorpost of each door, with the exception of the toilet and bathroom, has a mezuzah scroll inside a metal, wooden or plastic case affixed to it. The mezuzah is a parchment on which the first two paragraphs of the Shema are written. It signifies to the Jew that his home is a place where God’s presence dwells, and it reminds him of his religious duties. The food the Orthodox Jew eats is determined by the Jewish dietary laws. These forbid eating all animals which do not have a cloven hoof and chew the cud, all birds which are birds of prey, and all sea creatures which do not have fins and scales. Kosher (i.e. fit) animals have to be ritually slaughtered, certain forbidden parts removed, and the meat salted to remove the blood before it can be eaten. Meat and milk cannot be cooked or eaten together, and different kitchen utensils must be used for them. It is also necessary to wait for a period of time after eating meat before milk dishes can be eaten. The Jewish kitchen and Jewish cuisine therefore have a distinctive character, and bring home to the Jew that even in this most basic mode of life he must serve God [33: XII].

On Sabbaths and festivals the family gather together for their meals, which are accompanied by hymns and grace before and after food. In general, no food may be eaten without a benediction acclaiming God as the creator and producer of the objects being consumed, and a prayer is to be said afterwards thanking God. Before bread is consumed the hands must be ritually washed, as they must be on arising in the morning from a night’s sleep. Benedictions are said after going to the toilet, when the hands must be washed, before going to sleep at night, on smelling spices, on hearing thunder and seeing lightning, on seeing a rainbow, or even on hearing good or bad news. Life at home, for the Orthodox Jew, is structured round a religious framework which affects both the individual and the family.

The Jew’s dress is also subject to halakhic rules. We have already mentioned the custom for males of wearing a head covering at all times and for married women of covering their hair. Clothes must not be woven from a mixture of wool and linen, and some Jews even continue to wear the style of garments which were common in Europe before Jewish emancipation. There is no halakhic requirement to wear the black hats and long black coats, or for the Sabbath the fur-rimmed caps, silk coats and white socks which Chasidic Jews dress in. Those who do insist upon them, however, feel that to abandon them would be too much of a concession to modern ways [19: XXIV]. The male Jew has to wear a four-cornered vest-like garment with strings attached to each corner. This is a miniature version of the fringed shawl (tallit) worn during morning prayers, which on weekday mornings accompanies the arm and head phylacteries (tefillin). Phylacteries consist of leather boxes, painted black, held in place by black leather straps. In the boxes are scrolls of parchment with various passages from the Pentateuch inscribed on them. These specifically ritual items of apparel are based on biblical commandments, but their effect on the Jew is to remind him that his life and activities must be oriented to God and to the fulfilment of the mitzvot.

Most of our knowledge about Judaism in the past comes from religious literature which reflects the beliefs and attitudes of its authors, an intellectual elite. There is considerable evidence, however, concerning the beliefs and outlook of the ordinary, unlettered Jew in the pre-modern period. Some of this is contained in rabbinical literature itself, having been taken over and developed from oral motifs as a means of exemplifying religious truths and values. Many of the collections of midrashim, or homiletic commentaries on the Bible, edited during the first millennium of the Christian era, are replete with folkloristic themes [10]. To later readers the midrashic tales, originally meant to clothe an abstract idea or ethical principle, represented the literal truth about historical events. Angels, demons, magical powers, ascents to heaven, wise animals and birds, and all the other features of folklore were thus sanctioned as part of the Jewish tradition, and were used for oral transmission and embellishment. Jewish mystical texts also reflect this pattern. They use images from popular religion to symbolize mystical doctrine, and because of the awe in which kabbalistic teachings were held by ordinary Jews many of these images were accepted literally in popular belief [27: VI]. This is examplified by the kabbalistic practice of making a golem or artificial man. For the mystics this was essentially a spiritual exercise, being a certain stage in the kabbalist’s inner development [28: V]. For the wider Jewish populace the making of a golem was a real act of magic power, and many legends circulated about wonder-working mystics and the doings of the golems they had created [32: 84]. The philosopher-theologians of the middle ages fought against the excesses of the popular imagination, their belief in semi-mythological beings, their literal approach both to the Bible and to rabbinical literature. They saw Jewish monotheism being qualified by the belief in angels and demons, by an interest in magic rather than in prayer and the service of God.

Over the centuries the attempts of the medieval philosophers bore fruit, and limited the extent to which folk religion developed. However, even the impact of the European Enlightenment, which has deeply affected Jews since the early nineteenth century, did not quite eradicate the belief in and practice of magic and superstition. These continued to exist side by side with the official religion in which the worship of the one, true God was taught. From early rabbinical literature onwards we find a divergence in attitude towards the mitzvot, some rabbis seeing the commandments as having only one purpose, i.e. enabling man to refine himself in the service of God, while other rabbis understood them as means for affecting the spiritual/physical condition of man, the environment, and even the state of higher levels of reality. The way halakhic rules were finalized often reflected the first interpretation of the mitzvot, and this is also the view of them that appears in medieval philosophical literature. Under kabbalistic influence the second interpretation gradually dominated the halakhic outlook, and acted as a conserving force, since any changes in ritual had to contend with the belief that the ritual was the means of maintaining harmony in the universe and therefore was sacrosanct [28: IV]. The popular approach to the mitzvot also invariably preferred the view of ritual in which it is operative as a quasi-magical force, and in folk religion halakhically prescribed ritual and purely magical practices coexist and are interwoven. Some newly introduced rituals were severely attacked by scholars, who believed them to be magical practices infiltrating the halakhic nexus. A case in point is the custom of slaughtering a chicken just before the Day of Atonement. The thirteenth-century Spanish talmudist, Rabbi Solomon ibn Adret, fought to eradicate this custom in his city on the grounds that it was a forbidden magical practice. A later scholar, the sixteenth-century author of the main halakhic code, the Shulchan Arukh, also sought to discourage this custom. Nevertheless it won widespread popular approval and the support of other rabbis, and eventually was taken up by standard works on Jewish ritual.

Magical practices were widely used by unlettered Jews for a variety of purposes. Many magical prescriptions, known as segullot, circulated to deal with ill health, barrenness, lack of love between a man and a woman, the evil eye, burglary, a bad memory, the need to discover whether a missing relative was still alive, witches’ spells against people, children who cry continually, astrological forces, protection against bullets, difficult childbirth, unsuccessful business dealings, fire, storms at sea, imprisonment, drunkenness, etc. [10: IX, X]. Some of these belong to the sphere of folk medicine, while others involve purely magical remedies [36: VIII]. The purveyors of this magic, known as baalei shem (singular baal shem), were itinerant wonder-workers catering for a clientele of mostly poor, semi-literate Jews. The founder of the Chasidic movement, R. Israel ben Eliezer (1700–60), began his career as a wonder-working faith-healer, hence his title Israel Baal Shem Tov [19: III]. Another semi-magical practice, found among both Ashkenazi Jews in eastern Europe and Sefardi-oriental Jews in Islamic lands, involved visiting the graves of dead holy men. A request might be written on a piece of paper and deposited inside the tomb on the site of the burial, or candles burnt. Sometimes the tomb was measured out in coloured string or candle wick. The idea behind these and similar practices was that the spirit of the deceased should intercede on behalf of the visitor, or that being in the mere presence of the mortal remains of such a saintly and powerful person would be of benefit. Criticism was directed against such practices by the rabbinical leadership, but ultimately they were unable to prevent Jews seeking out the help of the dead, even if there were ample warnings against such behaviour in early Jewish literature.

In the modern period people’s exposure to scientific assumptions about the world and to secular education has meant that many of the magical procedures of the past are no longer practised. Ashkenazi Jews who still preserve the culture of the pre-modern ghetto, and who consciously reject some of the advances in the human outlook on the world, are likely to continue folk religion. This is even more true of the older generation of Sefardi-oriental Jews in Israel who have not received a modern education. For such Jews the evil eye, the machinations of demons, and the need for protective amulets against miscarriage and misfortune are part of the very reality of the world they inhabit. Magic fills the gap between their belief in God who has created heaven and earth and demands of the Jew that he fulfil the Commandments, and their immediate experience of life. There is no essential conflict between their monotheistic theology and their belief that the space between man and God is populated by a host of lesser powers at work.

The nineteenth and twentieth centuries have seen some of the greatest changes in Judaism since it underwent its dramatic transformation after the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE. In the latter part of the eighteenth century Jews in Germany and in France began to move outside the confines of their cultural ghetto and to participate in the intellectual life of Europe. Their emancipation and acceptance as citizens, rather than as aliens, was still to come, but some managed to surmount the obstacles in the path of the Jew and attained a measure of equality with their Christian fellow countrymen. One of these was Moses Mendelssohn (1729–86), who as a young boy moved on his own to Berlin, taught himself Latin, European languages and other secular subjects, and attained considerable renown as a German writer and philosopher. Though he encountered anti-Semitism among some of his Christian contacts, and suspicion among his less modernizing co-religionists, he believed that a new age was dawning for the Jews. He encouraged them to learn German and cease using their Yiddish dialect. He urged them to study secular subjects, acquire a trade, and prepare themselves to become part of the wider community. At the same time, however, he wanted them to preserve their Jewish traditions and himself remained an Orthodox Jew. In succeeding generations many of those who followed Mendelssohn’s lead went beyond their mentor’s intentions. They found that the easiest method of acceptance into Christian society was to undergo baptism and shed their Jewish identity. The gap between Mendelssohn’s view of Judaism and the somewhat liberal Christianity of their contemporaries did not seem large enough to warrant maintaining separate Jewish existence with all its inherent problems [33: 71; 22: III; 23: 46; 14: 255].

Some Jews in the post-Mendelssohn era did not wish to lose their identity as Jews, but could not identify with the ghetto-type Judaism of the majority of their co-religionists. They could not believe in all of the teachings of traditional Judaism, nor did they feel comfortable with aspects of synagogue ritual. They began, in their different ways, to introduce changes which were the forerunners of those associated with the later movement known as Reform Judaism. The areas of concern were the continued use of Hebrew rather than German in services; the references in the liturgy to the return of the Jews to the Holy Land in the messianic age, which implied that Jews could not be regarded as loyal citizens of their country of residence; their preference for the use of an organ and choir in synagogue, which was not common practice in traditional communities; and the need for a regular sermon in the vernacular [22: 156].

During the first few decades of the nineteenth century new-style synagogues, known as temples, spread both in Germany and in other European countries. Their practices were opposed by the Orthodox rabbis, and both sides appealed for support to the government authorities. Gradually the reforming movement was taken over by intellectuals who began to formulate its ideological platform. The main assumption of this ideology was that Judaism was a historical religion developing through time, and that it had to change in line with the new conditions it was facing. A number of conferences of reforming rabbis were called in the 1840s at which there was some disagreement between those who favoured radical change, since Judaism was essentially a religion of ethical monotheism to which ritual was extraneous, and those who wished to preserve elements of the tradition. The conferences tried to dissociate themselves from those reforming movements which sought to abolish all ritual expression, but nevertheless took up a radical stance on some issues which alienated the moderates. In general the history of Reform Judaism in Germany was one of modified traditionalism, with only a small number of communities adopting a radical approach to the mitzvot. The same was true of Reform Judaism in Britain, which began in the 1840s. It was only with the beginning of Liberal Judaism in Britain, in the early twentieth century, that the more extreme reforming position was institutionalized [29: 161]. In the US, by contrast, the radical tendency predominated in Reform Judaism from the 1880s.

Underlying Reform Judaism was the belief that a new age of tolerance was dawning for mankind, and that Jews would be accepted by the Christian world as equals. This optimism has gradually diminished, particularly in the light of Nazi atrocities and the support they had from European anti-Semitic movements. Today Reform Judaism is strongly Zionist in orientation, whereas it was once very hostile to nationalistic elements in Judaism. There is also a much more positive approach to Jewish ritual and to more traditional themes of Jewish theology among Reform Jews in the Western world. The antagonism between Orthodoxy and Reform, which characterized the early history of the latter movement, is still very much a feature of their relationship today.

An offshoot of the more traditionalist branch of movements for reform in Judaism was the Conservative movement in the US. This was begun in the mid-nineteenth century by European Jews who wanted to modify old-style Orthodoxy in the face of the realities of American life. They did not approve of Reform Judaism, and took as their model the attitudes of the European Historical school which affirmed the validity of the Jewish past as well as the need for Jews to modernize [22: VIII, XIII]. After a slow start Conservativism began to expand at the end of the nineteenth century when the radicalness of the Reform platform made any attempt at compromise with official American Reform impossible. Conservative Judaism set up its own training college for rabbis, its own synagogue and rabbinical organizations. Today it is the biggest organized stream within North American Jewry, with branches throughout the US and Canada [30: 254]. It claims to be the authentic continuation of the rabbinical Judaism of the pre-modern period, but the many changes it has introduced into Jewish ritual and the doctrinal position of some of its proponents have led Orthodox rabbis to outright condemnation of its institutions. During the 1920s Mordecai Kaplan, a member of staff of the Conservative rabbinical seminary, developed a new, more naturalistic theology of Judaism which eventually led to the founding of the Reconstructionist movement as a breakaway from Conservative Judaism. Reconstructionism has adopted a more radical stance towards changes in ritual and doctrine, but its appeal has mostly been to intellectuals and it has not won a large following [33: 219; 30: 241; 23: 535]. Conservativism has found its main support among traditionally minded reformers or modernist traditionalists. Its success in North America is due, in part, to the rejection of traditional mores by Reform Judaism there. In Britain, by contrast, it has had very limited success owing both to the greater moderation of British Reform and to the nature of Orthodoxy organized into the United Synagogue in London. Many of the United Synagogue communities are very modernist in outlook, and in an American context would be considered Conservative. In Britain, however, they affiliate to an Orthodox organization.

The general response of Orthodoxy to reforms was to affirm the divine basis of Judaism and to deny that man could simply change God’s teaching at his convenience. In practice, however, two different approaches were taken. Many of the leading rabbis in eastern Europe closed ranks against any changes in Jewish life, even of a minor nature, since they suspected change to be a hallmark of Reform. Hungarian Orthodoxy took a lead in this position, but it was equally strong among Chasidic groups who forbade their members to study secular subjects or even to change their style of dress. The other response was to accept modernity and the culture of European Enlightenment, but to maintain the rituals and doctrines of traditional Judaism. The most important genre of this type of synthesis was the movement of German Neo-Orthodoxy founded in Frankfurt by S. R. Hirsch. In opposition to those who saw Judaism as a historically evolving religion, Hirsch argued that it was a system of symbols, encapsulated in ritual, and that these symbols were equally valid in each age [33: 221; 22: IX].

The varied religious responses to Jewish emancipation were not felt to be satisfactory by many of the more assimilated Jews in the late nineteenth century. The problem as they saw it was that anti-Semitism was endemic in the Christian culture of Europe, and that Jews would not be accepted as equals however much they shed their Jewish identity. Under the influence of nationalist movements in central Europe Jewish thinkers started to advocate Jewish national revival, seeing the Jews not as a religious entity but as an ethnic group whose members shared historical memory and a common culture. This contrasted markedly with the Reform view that Jews were Germans, French or Britons of the Mosaic faith. Most of the nationalists, later known as Zionists, were completely secular in their outlook. They wished to see Jews established in their own homeland where they would at least be free from anti-Semitic prejudice. Jews would then be able to develop like any other nation [22: 305; 23: XIII]. The most important Zionist leader was Theodor Herzl (1860–1904), who is known as the founder of Zionism as a political movement. Herzl came to believe in Jewish nationalism after his experiences of French anti-Semitism during the notorious Dreyfus Affair in Paris in the 1890s, when a Jewish captain in the French army was falsely accused of spying. If France, the most highly cultured European country, could be the seat of such virulent anti-Jewish feeling then the idea that one day Jews would be accepted as equal members of Christian society was merely a pipe-dream. Herzl called together the various Zionist groups to attend the first Zionist congress in 1897, and spent the rest of his short life in seeking the backing of a major power for his goal of a Jewish homeland [11: III]. During the early twentieth century the Zionist movement grew, and groups of Jews went to resettle Palestine, the ancient homeland of the Jewish people, which was part of the Turkish empire and subsequently controlled by Britain under a mandate from the League of Nations. The Nazi-inspired massacres of 6 million Jewish civilians during the Second World War convinced many of the remaining Jews that a Jewish state was an absolute necessity. It also stimulated the United Nations to recognize the State of Israel, which was set up on 14 May 1948. The Arab countries of the Middle East were strongly opposed both to the existence of a non-Arab state in the centre of what they saw as essentially Arab territory, and to the mass immigration of Jews from all over the world to Israel [23: 559]. They fought a number of wars, including those of 1967 and 1973, with the aim of eliminating Israel and driving out the Jewish population. Although they had little purely military success the wars, and the political pressure backed up by the power of Arab oil, have meant that Israel has found itself constantly threatened since its inception. There has been considerable pressure on Israel to agree to the setting up of a Palestinian state in areas occupied by the Israelis since the Six-Day War (1967), but the Israeli government has not as yet agreed to such a solution to the problems of the area, despite the current peace process.

The effect of all this on world Jewry has been profound. The shock of the Nazi Holocaust has made Jews much more aware of their insecurity and the depths of prejudice against them. Support for Zionism is strong, and for many Jews in the West Zionism has filled the gap in their sense of Jewish identity left by the diminishing of purely religious belief and rituals. Israel’s isolation and the Arabinspired resolution of the United Nations equating Zionism with racism have convinced many Jews that anti-Semitic prejudice did not end with the fall of the Hitler regime. It seems to be a permanent feature of the Gentile world’s relationship to the Jew, with the State of Israel the only place where Jews can live without fear that their Jewishness may one day lead to a resurgence of the alienation and victimization that has characterized their existence down the ages. Israel also provides a spiritual focus for the Jews in the diaspora. Its achievements have helped to enhance Jewish dignity, badly shaken by the Nazi atrocities. Its holy places serve as centres for visiting Jewish pilgrims (see figure 1.8), and its religious leadership is looked to for guidance on issues which confront the traditional Jew in the modern world. The return of the Jews to Zion and Jerusalem, foretold by the biblical prophets as events associated with the onset of the messianic era, signifies that God has not forsaken his covenant or special relationship with the people of Israel. For many Jews this ‘ingathering of the exiles’ represents the beginning of a new epoch, perhaps the start of the messianic times themselves [33: 90].

Over the centuries Judaism provided the framework, not merely for a set of religious beliefs and rituals, but also for a total cultural complex which Jews carried with them on their many migrations through different countries and host cultures. Even when they were relatively isolated from their surroundings, living in ghettos both for their own protection and because they were treated as social outcasts by their Gentile neighbours, they still borrowed from their general cultural habitat. These continuous additions to Jewish culture can be shown simply by comparing the distinctive languages, dress, food, literature, music and art forms of Jewish communities with these features in their Gentile environment. The parallels between the two are marked, and the cultural differences between various Jewish subgroups are attributable in large measure to the influence of their different surroundings.

What was absorbed by Jews from the particular setting in which they lived, however, was rarely simply taken up wholesale. In every area of cultural life it was Judaism that determined both what was absorbable and the manner in which it came to be part of Jewish lore. Thus the cultural elements of Jewish life are an amalgam of early Hebraic forms and continually added new forms. The latter were Judaized, that is, they were adapted to the existing cultural framework, so they could be readily integrated as part of an organic whole [34: 16, 18].

Basic to the expression of Jewish artistic creativity, in its most general sense, is the limited place of the visual in Judaism. The biblical and post-biblical antagonism to representative art, particularly three-dimensional forms, emerges from the need to avoid idolatry, i.e. the association of any objects or representations with God himself [13: IV]. Although in the synagogue art of the early Christian period biblical scenes feature on wall paintings and on mosaics, with a large representational element of human and animal motifs, the opposition to such art was widespread both prior to and during this period. Josephus, the first-century CE Jewish historian, reports popular unrest at Roman attempts to set up figures or military insignia in Jerusalem. Early rabbinical works contain views prohibiting art even if used for purely decorative purposes, since this is an extension of the biblical injunction, contained in the Decalogue (Exodus 20: 4–5), not to make a graven image. In the middle ages these iconoclastic tendencies characterize much of rabbinical thought, and the revulsion at representational art was strengthened by the influence of Islamic views on the subject. Jews also clearly felt the need to distance themselves from the icons, statues and paintings of the Christian churches, which were felt to be idolatrous. This is not to say that visual art had no form of expression among Jews of the premodern period, but rather that it was severely limited. An important outlet for visual art was in the shaping of artefacts for ritual purposes, often in precious or semi-precious metals (candelabra, spice boxes, marriage rings, as well as synagogue furnishings and tapestries, scribal arts, the illumination of manuscripts, etc.). The many rituals of Judaism in the home and the synagogue, the festivals of the Jewish year, and the central place played by religious texts of all types allowed Jewish craftsmen, and Jewish patrons employing non-Jewish craftsmen, to develop distinctive art forms.

The main cultural expression of Jewish creativity was, however, not in visual art but through musical, oral and literary forms. There was less danger of idolatry in the literary and story-telling imagination, and though the religious authorities were wary of heretical ideas finding their way into untrammelled flights of fancy, they had much less control over the dissemination of this cultural form than over visual art. The poetry, hymns and aggadic (legendary) stories, and the great flowering of mystical speculation as well as the many fables of Jewish folklore, are all expressions of this emphasis on non-visual creativity [32: II]. Were the images of the Kabbalah, with its interpretation of the ten aspects of the Godhead as mother and father, son and daughter, lover and beloved, and its understanding of all reality, both human and divine, as made up out of male and female elements, to have found iconographic expression they would have posed a major problem for Jewish monotheism. As it was they remained in oral forms and, after overcoming some opposition to their wider dissemination, also in literary forms. Jewish music has characteristically been expressed in liturgical form, both in the synagogue and in the home. Hymn singing, the chanting of prayers and the reading of Hebrew scripture to a fixed musical notation have long been a basic part of Jewish life. On more joyous occasions, such as family celebrations or festivals, dancing and instrumental music (e.g. for weddings) are quite common, although the different Jewish communities were influenced by the non-Jewish musical forms of their host cultures.

The cultural preference in Judaism for the primacy of the word (whether sung, spoken or written) over the visual object has had a more general effect on Jews, in both the pre-modern and modern periods. Jewish communities have frequently been uprooted from their areas of settlement and been forced to move across provincial or national boundaries to re-establish themselves once more in a new environment. Such moves were often accompanied by anti-Jewish turmoil, in which the refugees managed to salvage little of the material possessions which they owned in their old locale. Migrations and expulsions would normally completely disrupt the cultural life of the community because of the loss of the synagogues and of the works of art. The fact that Jews had mainly a musical, oral and literary culture enabled them to survive and to carry the main forms of their culture from place to place. In the modern world the cultural bias of Judaism, favouring verbal expression, has influenced Jews even far removed from their religious roots to find creative outlets in theatre, novels, films, poetry, singing and in music rather than in sculpture and the visual arts.

In the last few decades dramatic changes have taken place in Jewish life, both in the State of Israel and among diaspora Jewry. Some of these changes are reflections of the age, such as the response to a new awareness on the part of Jewish women influenced by feminism, or the efforts of Jewish law to deal with the massive development of biotechnology and new medical techniques. Others are the consequences of shifts on the world political scene, such as the break-up of the old Soviet Union and the massive migration of ex-Soviet Jews to Israel, or the new order in the Middle East brought about by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. The Gulf War which followed the latter led to a shake-up of old alliances in the Arab world, and subsequently to peace negotiations between Israel, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and certain Arab states.

Overshadowing many of the innovations among world Jewry one can detect the dark cloud of the Holocaust, whose power seems to increase in Jewish consciousness, paradoxically, as the number of surviving victims gradually diminishes. Interestingly, there is a marked preference among Jewish writers for the use of the Hebrew term shoah, ‘destruction’, rather than the more commonly used term ‘Holocaust’. The latter refers to those sacrifices that were completely burnt after being offered up in the Temple ritual in ancient times. Using such a term to refer to the genocide of the Nazis and their allies is deemed inappropriate, for it seems to depict the Nazis as priestly figures offering up the Jews as sacrificial victims. Shoah, by its very name, simply indicates the negativity and desolation which the period of Nazi rules conjures up in Jewish consciousness.